Abstract

This paper reports on a systematic review of the literature around governance and water infrastructure in England to analyse data on the application, or absence, of justice themes. It finds that, unlike in other sectors, justice thinking is far from embedded in the water sector here and whilst there are signs of a discussion there is a lack of sophistication and coherence around the debate. More positively, the research suggests that the concept of justice can be used as a tool or framework to help air and address these complex issues and in doing so is an advance on the concept of sustainability. By exploring the issues in this way, the study reveals a wealth of opportunities to use justice-thinking to improve infrastructure decision making. It is suggested a justice approach is the next step as our thinking matures beyond sustainability, improving the decisions we make for people and planet.

Keywords:

justice; water; infrastructure; wastewater; governance; sustainability; systematic literature review 1. Introduction

Water is a precious, life essential resource that, in England, a country often maligned for its wet weather, is often taken for granted. However, as a nation it is not immune from the crisis confronting the rest of the planet, notably because the context changes greatly from south to north, and east to west. Indeed, the National Infrastructure Commission stated “The risk of households having their supplies rationed because there is not enough water is significant. Large and densely populated parts of England have lower annual rainfall than Sydney and Mexico City” [1]. Added to this geographical disparity, England is facing changing weather patterns, leading to climate-induced water shortages and irreversible damage to its ecosystems as a combination of climate change, population growth and unsustainable practices [2].

Interventions into our water infrastructure are needed if we are to address the environmental and social issues of the water crisis [1]. However, in doing so, we are making choices about how the benefits and the consequences of those interventions are going to be distributed. Areas that bear the brunt of disruptive infrastructure construction for example, may not be the same areas that that reap the benefits of its implementation; societal and environmental impacts or the opportunities afforded by the intervention may not be felt uniformly. The cost of infrastructure also needs to be assessed both financially and more broadly to include how in providing for humans now we impact on future generations or how we may devastate non-human life. In addressing these issues we are making choices about ‘winners and losers’ [3,4]. If water is essential for life then how we deal with its distribution through our infrastructure, how we govern our resources and address these tensions is a question of whether we have acted justly [4].

In the energy field at least, it is accepted that the ‘transition’ to sustainability should be just even if discussion in this area appears limited to economic impacts of the move to net zero carbon [5,6,7,8]. This is driven, at least in part, by the urgent need to move away from fossil fuels to greener forms of energy. Academic discourse on justice in the energy literature appears to be establishing itself [3,5,6,7], but it is emerging in other sectors such as transport as well [8,9]. The authors of this paper are not alone in noting its relative absence in infrastructure in the water sector, particularly in developed economies such as in England [10,11]. This leads to what appears to be a gap in discussions on infrastructure and governance in the water sector here; whether justice considerations are evident in how infrastructure interventions are framed and planned.

To fill this gap, this research asks, as we strive to adapt to the water crisis: is justice present in thinking around how we govern our water resources and infrastructure; and are justice themes evident in how we are seeking to ‘upgrade’ our water and wastewater infrastructure in response to our water needs? In an attempt to answer these questions the current authors undertook a systematic review of the literature around governance and water infrastructure in England to analyse evidence on the application, or absence, of justice themes. The systematic literature review process as outlined by Yigitcanlar et al. was adopted [12]. A systematic literature review makes clear the parameters used to search the literature ensuring openness, replicability and reducing the opportunities for bias. It is the ideal methodology to identify texts or search for terms and concepts within those texts. It allows the hypothesis, that justice thinking is mostly absent from those texts, to be clearly tested and any limitations in the research methods adopted to be clearly identifiable.

This study is set out as follows:

- Prior to commencing the systematic literature review what is meant by ‘justice’ needs to be explored and clearly set out. This study therefore starts by defining what is meant by ‘justice’ and explores themes around the concept. From those themes a framework of justice is created.

- The study then sets out the methodology for the systematic literature review and provides an overview of the data collected;

- This is followed by a more detailed discussion and analysis of the findings. The justice framework and themes is used to inform the analysis. This section includes a discussion on the limitations of the research methods deployed; and

- The conclusion seeks to answer the research questions and suggest further areas of research.

2. Key Concept: Justice

In considering justice it is first beneficial to understand the governance regime in England to provide context. There are many ways in which water supply and infrastructure can be owned and governed—for example, a commons approach as discussed in theories of social-ecological systems such as explored by Ostrom [13,14], municipal or state holding, market-based, or a hybrid scheme—and each regime has its advocates and detractors (for comparative case studies see [15,16]). It is argued below that each regime has its own impact on the application of justice.

Water governance in England is perhaps infamous for its privatisation in 1991, implemented at least in part to raise revenue for its ageing, under-funded infrastructure [17]. As regional water companies were set up to manage local monopolies of water and wastewater services, a series of institutional, regulatory and other governance mechanisms were initiated, and have since developed, to balance the need for water companies to make profit with affordability for their customers. A system of government, quasi-government, corporate and civil organisations are now involved in its management, epitomising the wider move from top-down government to ‘governance’ [18]. The implications of this fundamental change of regime, its impact on state and non-state actors, the view of water as a commodity and ‘citizens as consumers’ continue to be scrutinised [18,19,20,21]. As discussed later, it provides a context into which justice concepts are placed or where the regime and justice may be said to conflict.

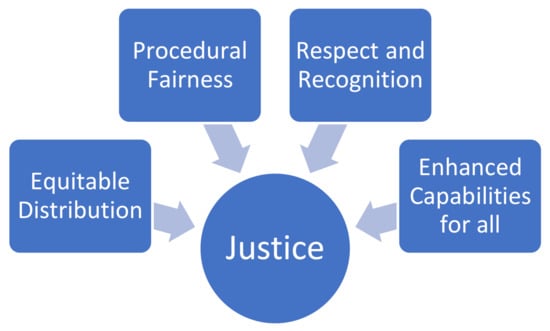

In defining and applying concepts of justice, reliance here is placed on Schlosberg’s widely cited work on environmental justice [22]. The reason for selection of this work is its comprehensive review of justice themes relevant to the tensions in governance of natural resources, such as water, and its interface with humanity [23,24,25]. It is a work that, through its breaking down of the concept of justice, enables it to be understood and applied to different contexts. The association with the concept of ‘just sustainability’ is also significant [26,27], the addition of the word ‘just’ expressly accepting in some way that sustainability alone is not ‘enough’. The discussion draws on bodies of work around justice to include different forms of justice—distributive, procedural, recognition (or respect), and ‘capacities’ (or capabilities), all of which can interconnect [22].

- Distributive justice is credited to the work of Rawls and justice as fairness [28], and addresses how resources, benefits and detriments are allocated amongst us. It accepts that there will always be ‘winners and losers’, but justice provides a mechanism for that to be as equitable and fair as possible. Where there is a distribution that is unequal, for example, that inequality should be to the benefit of the most disadvantaged [29]. It can be construed wider. A recent example is the ‘polluter pays’ principle, those who pollute being held responsible for the consequences.

- Procedural justice demands there should be access to justice and procedural fairness: it asks who participates, who decides and how a conflict is resolved, and is an important form of justice alongside distribution [30]. There have been moves to embed principles of access to information, public participation in decision-making and access to justice, particularly in the environmental arena as enshrined in agreements such as the Aarhus Convention [31] and mandated in the EU Water Framework Directive [32].

Procedural justice is all the more important when considering the model of governance and the multiplicity of bodies, rules and regulations that can apply in complex systems such as water infrastructure in England. A just governance system needs a process that allows multiple view-points to access it, to have the information they need and to have a forum to be listened to. Such a system can cut through the multiplicity of rules and players, inherent in ‘governance not government’, and allow the views of stakeholders to be aired, balanced and addressed [33].

- 3.

- Recognition and respect define procedural justice further to ensure that all voices are heard and respected in that process. Without recognition and respect there is no true voice, and it cannot be shown that a distribution or process is fair. In the absence of recognition, the processes lead to maldistribution [22]. This can be considered further when applying Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation [34] on the even more complex question of whether a process gives a true voice; whether there is tokenism or true engagement and empowerment.

The connection between recognition and infrastructure is noted in the struggle for equality in the US, with disadvantaged groups feeling targeted for the siting of undesirable development, (for examples see [25]). A study in the UK also flags issues of social peripheralisation, or lack of political capital, and the risk of infrastructure planners being attracted to those areas for interventions, noting,

‘projects tend to run smoother where there is a background of undemocratic processes and low levels of activism’([35] (p. 4); see also [6])

‘Smoother’ presumably meaning to some ‘implemented without troublesome objection’ or the absence of so-called ‘NIMBYs’ (Not In My Back Yard). Justice in recognition is connected to the absence of distributive justice in the allocation of benefits and detriments. A decision based on siting of an intervention—not where it is best, but on the path of least (human) resistance—would be at odds with this view of justice.

- 4.

- Capacities, or capabilities, is credited to separate works of Sen [36,37] and Nussbaum [38,39]. It encapsulates the three previous approaches but goes further in not simply seeking some form of fair dispute resolution. It has positive aims to improve the lives of living things. Its essence is that for justice, an individual must be enabled to have access to assets they need not just to survive, but to thrive. It can include the equitable distribution among us to achieve this, and how we participate and engage with due process and respect for those needs to be articulated and heard. It then goes further by addressing quality of life and well-being, by setting minimum standards that need to be achieved [22]. (For an example of the application of capability justice in infrastructure in practice, see [8]).

The capabilities approach, achieving well-being, sits well with the concept of ‘liveability’ and further helps express the need for distributive and procedural justice in achieving that goal, i.e., how resources are distributed fairly so one’s well-being is not at the unfair expense of another [40]. In terms of planetary well-being, academics such as Nussbaum and Holland extend the capabilities approach to living things more generally, justice being the equitable distribution, procedural recognition and fairness to achieve that required for a living thing to flourish, to fully function as itself as far as possible [39,41]. This view extends the question of ‘who’ should have a voice, from a limited human perspective into non-human systems of ecosystems and environmental well-being in its own right.

The justice issues extend to how we represent the interests of future generations, how the needs of future generations are spoken for and represented now—in fact this has been described as the key tension of our age [42]. Attesting to the currency of this debate, at the time of writing a Bill addressing some of these issues is making its way through the House of Lords [43]. Consideration of our future impacts in this way arguably joins the concepts of sustainability and justice together. Further, the authors of this paper argue that justice takes us beyond the concept of sustainability. Sustainability accepts there are three pillars —social, economic and environmental. Justice provides mechanisms for those often competing interests to be aired, judged and addressed. In addressing these questions, justice is more than a policy or law, although justice may be embodied in those instruments. Justice becomes part of our overarching Constitution [29] (p. 225), the driver for equity and fairness in our governance regime and a fundamental approach to how interests (current and future, human and non-human) are balanced.

It is these themes and articulation of justice that is taken forward into the study as shown in Figure 1. These themes form the basis of a framework.

Figure 1.

Framework: Themes of Justice in Water Infrastructure.

3. Materials and Methods

A systematic literature review was undertaken to identify and evaluate the extent that justice considerations were evident in literature on governance of water infrastructure in England. The aim was to focus on interventions in infrastructure systems, both what is being talked of and what has been implemented. The study therefore included grey literature addressing practical infrastructure issues on the ground through to literature addressing water governance at a purely academic or conceptual level.

The following search terms were identified:

- Water OR blue OR sew* (to allow for sewage, sewerage);

- Infrastructure OR intervention OR construction;

- Governance;

- UK OR “United Kingdom” OR Britain OR England.

Although the jurisdiction of interest was England, Britain and the UK were included in search terms. This was because despite the ongoing process of devolution, the UK still shares common elements of governance and articles of potential relevance to England could otherwise be excluded. Documents that reference the UK generally were included even if they did not include an express reference to England alone. Terms such as justice, equity, equitable and equality were included as a trial. This gave extremely low return rates, too small for a review. ‘Rights’ gave slightly more returns, although again too low, and mostly because of the use of the word in other contexts including ‘copyright’.

Three databases were used—Web of Science, ProQuest and Compendex (Engineering Village)—with a view to ensuring multiple disciplines were fairly covered. A review process in line with that proposed by Yigitcanlar et al. [12] was adopted. The application of that process in detail was as follows:

- The above search terms were applied to an ‘abstract, title or subject’ search firstly to the Compendex database giving 365 returns.

- The results were filtered using controlled terms relating to infrastructure, governance and water. This gave 72 returns. A test of a selection of excluded documents was undertaken to ensure the filters applied did not exclude legitimate documents.

- The duplicate filter then removed 11 documents, leaving 61.

- The abstracts were previewed to check consistency with the aim and scope of the study. Documents rejected included additional duplicates not filtered out previously, and documents that did not relate to England or where water or sewerage was not the predominant issue. Documents were excluded which could not be located online.

- Documents were not excluded on language or document type, i.e., grey literature was included.

- In total 28 documents were taken forward for a full review.

As an aside, a filter of ‘justice, equit* OR equality’ in the abstracts of the 61 documents referred to above resulted in no returns. ‘Rights’ resulted in 7.

The same process was applied to the Web of Science and then the ProQuest databases, producing initial search returns of 42 and 78, respectively. The filtering process resulted in 32 and 23 results to take forward.

The documents from the three databases were cumulated in Endnote software and duplicates removed. This resulted in 57 articles. These articles were reviewed in full. Some articles included reference to more than one jurisdiction. These were included as long as there was specific discussion on issues in England, for example comparisons between England and Australia or Europe. Similarly documents that had a specific discussion on water but also other sector interventions were included. Documents covering infrastructure generally without a specific focus on the water sector in England were excluded.

Of the 57 documents identified, 36 were found to match the criteria. These are exhibited in Table 1.

Table 1.

Categorisation of References to Justice in the literature.

4. Results

The 36 articles were read and compared, with the following classes identified.

36 documents were reviewed:

- 28 peer reviewed journal articles

- 5 journal articles, not peer reviewed

- 1 chapter in a book

- 1 lecture (video)

- 1 thesis

Date ranges:

- 1 from 1996

- 1 from 2005

- 7 between 2006 to 2010

- 11 from 2011 to 2015

- 16 from 2016 to 2020

Governance issues could be broken down as follows:

- 4 Policy

- 10 Law and regulation (excluding economic regulation)

- 4 Economic regulation only

- 8 Sector Regime including networks

- 1 Norms, values and behaviours

- 9 Multiple forms of the above

Infrastructure interventions included physical and non-physical interventions. There were 25 Physical interventions:

- 9 Water Re-Use/Rain Water Harvesting and Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS)

- 2 hydropower schemes

- 2 sewerage and wastewater treatment

- 2 urban blue landscaping

- 5 freshwater pipe network including reservoirs and abstraction, metering and retrofitting

- 4 flooding interventions including Natural Flood Management

- 1 synthetic biology

The 11 remaining, non-physical interventions included work around policy, finance and economics, regulation and planning and development.

Additional data recorded included the discipline of the author(s) where discernible, any nexus (e.g., energy, food, transport) and academic school of thought if any (e.g., socio-technical systems, socio-ecological systems, commons, transition management). No immediate trends were apparent other than the diverse range of interests and thinking.

The documents were reviewed for references and engagement with justice issues. Due to the relatively low number of documents this was capable of being undertaken by hand. Of the 36 documents only three contained an express reference to justice. These were defined as Category A. Due to the low returns, express references to equity, rights and equality were also searched for and identified. These were defined as Category B. As well as express references, themes around the justice principles of distribution, procedure, respect and capabilities were also highlighted, even though express references to the key terms themselves were absent. These were defined as Category C.

This left some 17 documents without a categorisation. However, during the review process the prevalence of the term ‘sustainability’ was noted. The documents were re-reviewed to note the use of this term and also ‘resilience’. In comparison to the three documents that contained an express reference to justice there were 27 documents that referenced sustainability and 14 for resilience. The 17 uncategorised documents were re-considered: 13 referred to sustainability and were defined as Category D, while the small balance of 4 documents that remained were defined as Category E. The articles and categories are summarised in Table 1.

The categories of most interest are those where justice is referred to either directly (A) or implicitly (B and C). The possible use of sustainability in lieu of justice was then considered through a review of all of the texts including those in Categories D and E.

5. Analysis

The focus of the analysis is on how the concept of justice is seen and used in the texts (or indeed its absence). These are found in Categories A, B and C. The analysis centres on how justice is dealt with in the Category A documents before ascertaining whether any additional themes can be gleaned from Categories B and C. In looking at themes the content of the texts is discussed and the framework containing themes (of distributive justice, procedural justice, respect and recognition and capability justice) is applied.

5.1. Category A

The three documents in Category A exemplify the diverse fields and interests in this field despite all three being grounded in issues of water, governance and infrastructure in England. Although all three refer directly to justice, justice is not the core theme in any of them, rather it is an issue that pervades the topics of interest to varying degrees.

Strang discusses the connection between water and power, in particular how it is mediated through the provision of infrastructure [45]. It addresses these issues through a historical narrative and in the context of the current market-based governance model chosen in the UK (as well as comparing this with experiences in Australia). It argues that a market-based regime, particularly where the corporate ‘owners’ of the infrastructure are international, can be detached from the communities they serve and may or may not choose to act in their best interests. With the separation of control of water infrastructure, the article raises governance questions over the role of the State (or lack of) and issues of legitimacy and accountability over the governing of a natural resource when left in the hands of a detached corporate body. This leads to the tension between market-led regimes and the social justice and ‘water rights’ movement—the fundamental difference in how water is viewed as a ‘common good’ versus the market-led view of water as a commodity. The article addresses how the market-led governance ‘regime’ is not simply a context or background for decision-making around water but more than this, it shapes roles, behaviours and attitudes to water more directly.

The link with justice is evident in discussions on the drive for sustainability and its encouragement of bottom-up, community participation; participation having the potential to address issues of legitimacy and accountability that could otherwise be lacking in this regime. It argues that problems arise when some groups are excluded from due process or where only the stronger voices are heard. In this way it is arguable whether the author is articulating a connection between sustainability and participatory justice, and particularly how important participatory justice becomes in this model. However, it is the tension between human and ecosystems that are aired most directly. The conflict and tensions with the needs of ecosystem health with the immediate needs of humanity is; in distributive justice terms, humanity taking the benefits of an intervention and the ecosystem bearing the burden. The connection between justice and sustainability is discernible in the powerful closing paragraph concerning the failure to balance of the needs of ecosystems and humans:

“And humans do not hold all of the cards. In the end, the environment itself, impartially and inexorably, will continue to respond to human expressions of agency and power through water: if these are unsustainable they will, quite simply, cease to be sustained”[45] (p. 318)

In looking at water as power through its control and distribution, that power appears to rest with humans but ultimately we will not have the final say. The human right to water has its natural limit when resources disappear for good.

Strang therefore addresses justice directly, but justice themes are also evident more diffusely through the work in issues of access to the governance system (participation) and the allocation of benefits and burdens (distribution), be those human-to-human or human-to-ecosystem [45]. It also highlights the importance of the governance regime in shaping roles and attitudes to water and infrastructure, and so where tensions with justice may arise.

Justice considerations in the paper by Brown et al. are more narrowly drawn [44]. The article discusses the results of engagement with the water services community through questionnaires and workshops with a view to ascertaining their research needs. The results are a series of questions that, it is argued, need to be addressed to deal with the current and anticipated challenges in the sector. The results are clearly aligned with the three pillars of sustainability since the questions cover a range of issues on economic, social and environmental topics, although there is a weighting towards environmental concerns. This is evident in the number of questions around how to value ecosystem services and balancing competing interests. The questions around balancing the interests of ecosystems could be construed as aligning with concepts of distributive justice.

There are 21 questions in the section dealing expressly with water infrastructure although none of the questions in that section expressly refer to justice. The majority of the questions are technical questions focussed on optimising efficiencies in the system. Although perhaps not the intention of the study, it is possible to draw on justice themes in considering and answering the questions raised. For example:

46. What would we do with sewage and water supply networks if we started afresh (and considered all factors such as changing climate, population and policy); is current technology up to the job?47. What would a modern water/wastewater treatment plant look like if we could start afresh?48. How do we develop and implement low energy water and wastewater treatment processes?50. Is local treatment more sustainable than a fully sewered system?53. What is the best solution to water supply over periods longer than the next 30 years, and what are the potential barriers to success? (citation)[44]

The questions could be read narrowly as seeking purely technical input (are we doing it right?), or more broadly asking if we could start again how can we aim higher and make the system more just (are we doing the right thing)? In the technical context within which these questions were aired it appears more likely that the narrow construction was intended. If so these questions will fail to address how we move to a ‘just transition’ and will represent a missed opportunity. It is submitted that if justice themes are applied they could help shape research or provide a framework of values to help answer them.

The Brown et al. text uses the term ‘social justice’. It is not defined but appears mostly limited to questions of water debt; for example:

78. How can ‘can’t pay’ water debtors be differentiated from ‘won’t pay’ debtors, and what pricing structures and measures are best able to deliver water justice and cost recovery?[44]

It is not clear what is meant by ‘water justice’, but the reference to payment and debtors implies affordability. This suggests the application of justice in narrow economic terms: justice demanding equity in terms of ability to pay for an essential service. As the participants were working within a market-led regime, in which users are customers, this is perhaps understandable as a reflection of the regime they are operating in. The market-led regime influencing how water and infrastructure is viewed has already been aired in the Strang article [45]. This narrow view leaves fundamental questions unaddressed; for example, over equality of provision and services, whether vulnerable or marginalised groups are going to feel the impact of water stress more acutely, and whether the benefits of infrastructure for well-being are available equitably.

Leading on from the application of justice in economic terms, the third text in Category A, Thaler and Priest, addresses the Partnership Funding Scheme for flooding infrastructure [46]. There is an anomaly in the article in that it does not actually lay out the key features of the scheme as the authors see it. Nevertheless, it is reasonably well known to be a provision for the funding for flood relief schemes, purportedly designed to encourage bottom-up participation in flood relief schemes, and in turn obtain buy-in locally for locally sensitive and sustainable interventions.

Justice and equity themes are noted in two connected areas in this text. Firstly, it raises questions over how the multiple levels of the governance regime operate in reality. This is an inherent issue in a governance regime with a more diffuse use of state and non-state actors than in a traditional, linear top-down government. With responsibility being moved down the hierarchy and closer to the communities, the question arises as to whether that comes with the power and funding to manage the risks: does the availability of funds and allocation of risk and responsibility align? This is stated to be an issue for the governance regime and how it shapes distributive and procedural justice concerns.

The second concerns the issue of community participation and whether this scheme provides the democratic legitimacy anticipated. As already noted in relation to Strang [45], participation can bring procedural fairness, but only if those contributing are truly representative and not limited to certain education, profession and class backgrounds. The concern is those with higher social and political capital are more likely to benefit from these types of opportunities, leaving other groups behind. Legitimacy can be linked to participation, but the participation must be just. The article again raises issues of procedural justice and justice through respect and recognition.

In summary Category A texts raise justice issues to varying degrees. Applying the justice framework (distribution, procedural, respect and recognition, and capability) the texts in this category raise the following points:

In terms of distributive justice there is evidence of discussion on how we distribute benefits and impacts between both human-to-human and human-to-ecosystem. This is seen in at least two of the texts albeit to varying degrees. There is also a discussion on how the market based regime, the regime used in England, may lead the debate towards narrowly drawn economic considerations of price and affordability—such debates are important but there is more to distribution of water and infrastructure services than price.

Participatory justice, Recognition and Respect are evident in discussions on the extent to which there is true participation in processes and whether the system is tipped in favour of the socially and politically advantaged. This arises in discussion on the governance regime itself. It is not necessarily that a market-based system is unjust per se, but it shapes the view of water, behaviour and power relations between levels of governance and in turn raises questions of democratic accountability, true representation and fairness.

Capability justice and discussions on how infrastructure can enhance capabilities appears to be missing from Category A texts. In considering the research aims of this study what also appears missing is:

- A clear articulation within the texts of what justice (or indeed equity, equality or rights) means in this sector.

- An articulation of the relationship between sustainability and justice.

5.2. Categories B and C

The discussion turns to the documents in Category B (no use of the term ‘justice’ but contains express references to ‘equity’, ‘equality’ or ‘rights’) and Category C (no express reference to the terms ‘justice’, ‘equity’, ‘equality’ or ‘right’s but justice themes are clearly articulated and discussed).

Similar themes to Category A are evident in the 8 Category B and 8 Category C documents. Although the themes are present the use of terms such as equity are rarely defined. In Category B for example, phrases of ‘rights’, ‘equity’ and ‘equality’ are used interchangeably.

The articles in categories B and C, raise similar issues over ‘true’ participation, respect and recognition and the disproportionate power of some lobbying or demographic groups [47,54]. Considerations of social justice in economic terms are seen in the article on water-metering [50], while pricing and discussions on the impacts of a market regime are also evident [49,51,53]. There is further articulation of effects of the change in regime from top-down ‘government’ to bottom-up ‘governance’, and the extent to which power/responsibility aligns with the availability of funds in practice [47,49].

In addressing water rights, a Category B article argues in defence of the market structure, commenting that the shaping of the debate around pricing in the water sector is confused [53]. The argument runs that it is not water pricing that is the problem, but poverty generally that needs to be addressed. The argument continues that shopkeepers and landlords are not tasked with reducing prices and improving affordability, so why is the water sector treated differently? The counter-argument, of course, is that water cannot be substituted for another ‘commodity’ [79] and most grocery stores and landlords are not operating in a monopoly. Nonetheless the article does address some of the benefits of a market approach and provides some balance to the debate.

However, the way arguments are framed around water rights and cost highlight a deeper problem—the narrowing of the debate to economic concerns and price. Justice is not just about affordability. This narrowness may be a consequence of the framing of the debate in ‘rights’ terms. The idea of ‘water rights’, as seen in Strang [45], is said to have evolved from campaigns against neo-liberalism in economics and the privatisation and commoditisation of water [79]. This may explain the leaning to economic considerations in how the debates are constructed as that is the basis upon which they were initially triggered. There are further potential problems. The human right to water and sanitation is enshrined in a UN resolution [80]. Nevertheless, a rights-based approach is not universally accepted as the best way forward—issues of enforceability, as with any international obligation of this nature, prevail but further, a rights-based approach is perceived by some to prioritise anthropocentric concerns and the entitlements of the individual [79,81]—the ‘me’ culture [47]. This limits the debate and does not embrace the complex nature of water, human and ecosystem concerns.

Justice and rights are not synonymous concepts and there are opportunities to learn from these criticisms. The justice themes as articulated here arguably address the critics of a rights-based approach as they lean outwards from individual concerns to communities, and non-human groups to wider impacts and principles, and most significantly contain an inherent acceptance of the inevitability of conflict (i.e., whose rights take precedence?) and the need for that to be addressed and resolved fairly. This scope is arguably beyond that achieved in the limited, albeit important, discussion on the right to water and its cost.

In addition to the augmentation of arguments already raised, further issues become apparent in Category B and C texts:

- Distributional issues specifically around the and ownership regime and its fitness for purpose;

- Capability Justice.

The Wells thesis articulates how the distribution of benefits and burdens around land ownership may not fit with current societal needs [54]. The thesis addresses these issues around natural flood management (NFM), an example of a more holistic, sustainable and land-sensitive approach to flood management, either as an alternative or supplement to hard infrastructure interventions. Exploring the issues flags the changing requirements of landowners, from farmers producing food (and an income), to stewards storing water for the benefit of others. As stewards they would not be producing an income nor necessarily benefiting their own land. Issues are raised in providing this public good over the responsibility for building and maintaining NFM interventions along with liabilities and risks. The experiences articulated in the thesis mirrored the first author’s own experience observing a flood forum meeting, where a farmer stood up and reminded the attendees that his role was actually to produce food.

Land, riparian and water laws have developed in English law over hundreds of years and not along a clear or linear path. There remain tensions between the common good, public goods and private rights, and the thesis serves to provide a recent example of where this impinges on sustainability. In articulating the benefits and burdens of NFM on communities, it also serves to flag questions of distributional justice. Those flags in turn ask questions of governance such as compensation for land use, the role of existing public bodies and subsidies. Since the thesis was drafted, the new post-Brexit Agricultural governance and subsidy regime has progressed. The extent to which governance issues are now resolved as viewed through a justice lens exceeds the remit of this study, albeit it would be worthy of review (for an overview see [82]).

Capability justice in terms of infrastructure for well-being and equality is mentioned but only in passing in the Collins lecture [47]. Applying a justice lens, however, leads this study to ask capability questions of two developments referred to in the texts—these two texts discuss two separate unconnected developments that involve urban, blue infrastructure designed for multiple purposes including well-being [52,68]. The developments in question are situated in relatively affluent areas in the South East [52] and Oxfordshire [68]. The benefits to well-being of blue infrastructure interventions are increasingly understood, with the Oxfordshire development in particular yielding a positive impact on house prices and health and well-being. The location of the developments in relatively affluent areas does not mean that they are in inherently unjust. However, without justice issues of enhancement of capabilities for all being aired, neither can it be said they are just. Are we confident these types of intervention that go beyond immediate function and enhance a local area are available to everyone? Is the divide between affluent and poor areas becoming wider? On the evidence from texts and discussions available for analysis it is not possible to say. A justice lens would demand that those issues are aired and highlights the potential benefits of a justice thinking to infrastructure decision making.

5.3. Sustainability

The final issue to be addressed in analysing the 36 selected texts is whether sustainability is used in lieu of justice. The term ‘sustainability’ appears widely embedded into water infrastructure discourse, as indicated by its reference in 27 of the 36 articles under consideration (in stark contrast with only three explicit references to justice). It was not to be expected that all 36 articles would refer to justice or sustainability, nor should they have done. The authors of the various texts came from diverse fields with varying interests and with different focusses for their work. What is notable in this study is the contrast between sustainability and justice in terms of the prevalence of the use of those terms. What it does suggest is that despite the range of texts, value-laden concepts such as sustainability, which ask questions on the wider impacts of an intervention beyond its technical success, can become part of the narrative even in technical arenas. In that respect, sustainability as a term and a concept is a success.

There remains a suspicion that sustainability could have become something viewed as so fundamentally ‘good’ that the fact that an intervention is sustainable is tantamount to it being right, equitable and just. Although this could reasonably be inferred, and advanced as a hypothesis, because of the way that the topic is now dealt with, drawing a firm conclusion from the texts was not possible. Sustainability was rarely defined in the texts and often used only in passing. Finding conceptual links through the literature was even more difficult. In Category A texts where justice at least was expressed, justice and sustainability were treated very differently. In the Strang article [45] the terms relate to separate, albeit linked, concepts, with an absence of justice leading to a loss of sustainability for example. Brown et al. [44] deal with justice more narrowly, arguably as an adjunct to sustainability as the more important driver. In Thaler and Priest [46], sustainability is not relevant to the issues they raise and is not mentioned at all. As a result of the lack of apparent consistency further research into justice and sustainability together should be considered.

6. Discussion

6.1. Issues Highlighted

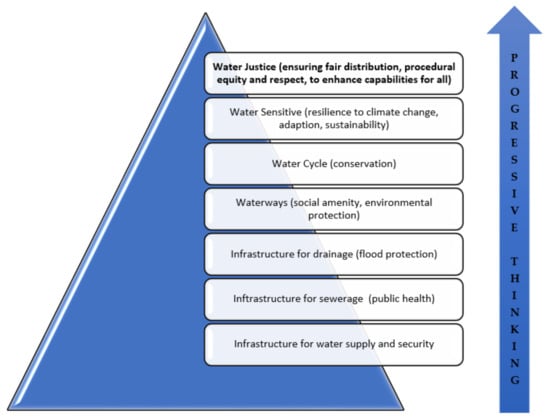

Drawing the discussions together a depiction of the issues highlighted is shown in Figure 2. This highlights the broad range and richness of issues that arise when viewing the literature with a justice lens. It provides a framework for asking questions of an intervention and its wider values and implications beyond sustainability. It asks questions of what we want when we look to the future. The issues highlighted in Figure 2 could be used as set of themes to be addressed when infrastructure changes are planned or implemented.

Figure 2.

Justice Issues as determined by the review.

Despite the issues elicited, however, in the past 10 years, only three of the texts articulate any issues around justice expressly and arguably only one does so to any significant degree. That is not to say justice type issues are entirely absent from the texts. There are concerns over inequalities, equity and rights as threads within the literature. The difficulty is that they are not articulated or applied in a coherent or consistent way. Even the terms themselves are used differently and/or interchangeably. There does not appear to be a consistent articulation of ‘justice’, ‘equity’ or ‘rights’. This arguably illustrates the lack of sophistication of justice narratives in this arena rather than a lack of need for justice as a concept.

Progress towards embedding ‘sustainability’ into the narratives around water infrastructure in England has been considerably more successful. Of the wide-ranging articles identified by the systematic review the overwhelming majority acknowledged the application of sustainability. There is some way to go before the same can be said of justice. The predominance of the concept of sustainability suggests it may be viewed as the ultimate goal to be achieved? Whilst sustainability must be a goal, it is submitted that it is not a determination on its own of what is ‘just’.

To articulate this further, reference is made to the article by Ashley et al. [83] for its depiction of the different aims of urban designers in cities and how those aims have evolved. Although showcasing urban design generally rather than infrastructure, it shows a progression of drivers relevant to water services over time from simple supply of water to the addition and development of sewage systems driven by public health concerns, to progress into water conservation and eventually up to resilience and sustainability. In this depiction sustainability is the highest goal. Drawing on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, it could be construed as a depiction of increasing aims once immediate needs are satisfied and the progression to more complex requirements [84].

To develop that thinking further, the authors of this study ask whether there should be one step further in that hierarchy suggested by Ashley et al. [83], i.e., beyond ‘sustainability’, the wider view of justice should be added to the top of that list. To highlight the point, the hierarchy suggested by Ashley et al. [83,85] is adapted and depicted in Figure 3 with ‘Water Justice’ added. This then depicts the progression beyond sustainability and further into what we want for our water infrastructure into the future.

Figure 3.

Water Justice as a higher paradigm. Adapted from [83] citing [85].

Endorsement for this approach can perhaps already be seen in operation in the ‘just transition’ agenda referred to above. It also presents an opportunity. Justice is not in competition with sustainability, it is its natural progression and can be used to address conflicts in balancing competing interests and needs. It can utilise the groundwork already laid by the sustainability agenda to move us up to higher level goals.

6.2. Limitations and Further Research

As with any systematic literature review, it is limited by the parameters chosen. In choosing those parameters it is then necessary to be clear about what the selected texts can show. The study is deliberately aimed at infrastructure to see what is happening in discussions around interventions ‘on the ground’, rather than solely at a conceptual level. The interest lies in what discussions there have been, if any, and how they have been encapsulated in the interventions that have been taken forward. It does not seek to include all water justice texts, although the lack of literature in this field generally, particularly in developed countries, has already been noted [10,11]. The limit to England may exclude other texts, but what is particular about the English system is its renowned system of privatisation. The link articulated between privatisation and the rise of the water rights movement may suggest it is more likely to prompt rights or justice arguments than not.

What also becomes clear is how the governance regime may frame justice arguments, making it essential that when considering water justice the full governance context is understood—and the dangers of drawing conclusions in one jurisdiction and applying it to another made clear.

Although the systematic review process should be objective, whether a document contained an implicit reference to justice, equity, rights or equality is unavoidably a matter of judgment. There is a risk of confirmation bias. To reduce the risk, the analytical review process paid attention to the articulation of the justice themes that were to be applied using a recognised and well-respected discussion on justice [25]. These themes were made clear in the framework.

There are three areas where it is suggested future research may be aimed. The first relates to the connection between water rights and justice—to explore the limitations of each concept, why water rights do not have a higher profile (certainly in England) and how the rise of energy justice may perhaps be adapted and utilised to fill the gap. The second is the relationship between sustainability and justice, notably how they can be utilised together. With sustainability already seemingly established, such research should study how justice can ride along with those narratives and move forward to enhance the debate. The third acknowledges that the study, for reasons given, is based in a single jurisdiction, England. Expanding the application of the justice framework to texts in other developed economies and low income countries is also suggested as research in this area is extended.

7. Conclusions

The case was made in the opening paragraphs of this paper for the need for justice in how we think of and improve our water infrastructure in England. With this in mind, the question asked was whether justice is embedded in current thinking. That only three texts out of 36 referred directly to justice (in comparison to 27 out of 36 that referred to sustainability) suggests the answer is ‘no’.

However, although justice thinking is not obviously referred to, it is still present. This study suggests a lack of sophistication in the justice debate, whether articulated as justice, equity, equality or rights, but not its absence. The multiple, disparate strands of thinking around justice-type themes evident in the texts may suggest we are inherently sensitive to potential injustices and that it does not need to feature explicitly—after all, it is a concept that is far older than sustainability and it is argued that the concept of sustainability should mature into one that permeates and influences thinking without explicit mention: it should become the accepted norm.

Nevertheless, there is encouragement that justice could resurface explicitly as a strong element of future arguments: in the same way that the concept of sustainability, which asks questions on the wider impacts of an intervention beyond its technical success, now routinely appears in discussions, it shows that the concept of justice can become part of the narrative even in technical arenas. Now that the issue of social justice is pervading many policy discourses and appearing in government priorities (e.g., the UK Government’s current commitment to ‘levelling up’), the opportunity exists to raise its importance when considering options and ensure, rather than tacitly assume, that it is embedded in practice. Crucially, the research has established a need to distinguish between the concepts of sustainability and justice—consideration and alignment with the former does not imply that the latter issue is addressed—and a solution is proposed: justice should be raised above the equally compelling needs for sustainability and resilience in a hierarchy of needs.

It is argued that as a species we have an innate sense of justice beyond a sense of injustice merely to ourselves [86]. Further, the wealth of issues raised and the underlining of gaps in our thinking suggest there is value in justice being more fully articulated and deployed in this context. If successful it is hoped we will be judged by future generations and the natural world more favourably.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.S.; methodology, E.A.S., D.V.L.H.; validation, E.A.S.; formal analysis, E.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.S.; writing—review and editing, D.V.L.H., C.D.F.R.; visualization, E.A.S.; supervision, D.V.L.H., C.D.F.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) under grants EP/R017727 (UK Collaboratorium for Research on Infrastructure and Cities Coordination Node) and EP/S016813 (Pervasive Sensing of Buried Pipes), and both EPSRC and United Utilities for supporting the doctoral research study of the first author, of which this is a part.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- NIC. Preparing for a Drier Future. Crown Copyright. 2018. Available online: https://nic.org.uk/studies-reports/national-infrastructure-assessment/national-infrastructure-assessment-1/preparing-for-a-drier-future/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Environment Agency. Meeting our Future Water Needs; Environment Agency: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, R.; Foxon, T.J. A socio-technical perspective on low carbon investment challenges–Insights for UK energy policy. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 14, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.; Jackson, S.J.; Bowker, G.C.; Knobel, C.P. Understanding Infrastructure: Dynamics, Tensions, and Design; Deep Blue: Ann Arbor, Michigan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, N.; Barry, J. Politicizing energy justice and energy system transitions: Fossil fuel divestment and a “just transition”. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.; Cooper, C. The Governance of Energy Megaprojects; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 1–254. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Burke, M.; Baker, L.; Kotikalapudi, C.K.; Wlokas, H. New frontiers and conceptual frameworks for energy justice. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hananel, R.; Berechman, J. Justice and transportation decision-making: The capabilities approach. Transp. Policy 2016, 49, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.H.M.; Schwanen, T.; Banister, D. Distributive justice and equity in transportation. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstead, K.; Aiken, G.T.; Eadson, W.; Braunholtz-Speight, T. Putting community to use in environmental policy making: Emerging trends in Scotland and the UK. Geogr. Compass 2018, 12, e12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özerol, G.; Kruijf, J.V.-D.; Brisbois, M.C.; Flores, C.C.; Deekshit, P.; Girard, C.; Knieper, C.; Mirnezami, S.J.; Ortega-Reig, M.; Ranjan, P.; et al. Comparative studies of water governance: A systematic review. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; DeSouza, K.C.; Butler, L.; Roozkhosh, F. Contributions and Risks of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Building Smarter Cities: Insights from a Systematic Review of the Literature. Energies 2020, 13, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action/Elinor Ostrom; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2010, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osbeck, M.; Berninger, K.; Andersson, K.; Kuldna, P.; Weitz, N.; Granit, J.; Larsson, L. Water Governance in Europe: Insights from Spain, the UK, Finland and Estonia; Swedish All Party Committee on Environmental Objectives (Miljömålsberedningen): Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse, P.; Muller, M. Water Governance—An Historical Perspective on Current Debates. World Dev. 2017, 92, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofwat DEFRA. The Development of the Water Industry in England and Wales. 2006. Available online: https://www.ofwat.gov.uk/publication/the-development-of-the-water-industry-in-england-and-wales/ (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Walker, G. Water Scarcity in England and Wales as a failure of (meta) Governance Water Alternatives. Interdiscip. J. Water Politics Dev. 2014, 7, 388–413. [Google Scholar]

- Commons, H.O. Regulation of the Water Industry, 8th Report Sessions; Parliament, G.B., Ed.; Stationery Office: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, N.; Collins, K.; Ison, R.; Blackmore, C. Water Governance in England: Improving Understandings and Practices through Systemic Co-Inquiry. Water 2016, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N.; Deeming, H.; Treffny, R. Beyond bureaucracy? Assessing Institutional Change in the Governance of Water in England and Wales. Water Altern. 2009, 2, 448–460. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, D. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; Quinn, T.; Lorenzoni, I.; Murphy, C. Sharing the Pain: Perceptions of Fairness Affect Private and Public Response to Hazards. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2016, 106, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, D.; Parkhill, K.A.; Corner, A.; Vaughan, N.E.; Pidgeon, N.F. Public conceptions of justice in climate engineering: Evidence from secondary analysis of public deliberation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 41, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, J.; Bullard, R.D.; Evans, B. Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World; Agyeman, J., Bullard, R.D., Evans, B., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, D.; Collins, L.B. From environmental to climate justice: Climate change and the discourse of environmental justice. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. A theory of Justice Revised Edition, 1999th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. Justice as Fairness: Political Not Metaphysical. Equal. Lib. 1991, 14, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, R.; Fawcett, T.; Hyams, K. Climate justice and energy: Applying international principles to UK residential energy policy. Local Environ. 2016, 22, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters, Aarhus, Denmark on 25 June 1998. 2021. Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/env/pp/documents/cep43e.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- European Parliament and Council. Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC, Official Journal (OJ L 3327), Brussels 22 December. 2000. Available online: http://www.worldlibrary.in/articles/eng/Water_Framework_Directive (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Larcom, S.; van Gevelt, T. Regulating the water-energy-food nexus: Interdependencies, transaction costs and procedural justice. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 72, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rubens, G.Z.; Noel, L. The non-technical barriers to large scale electricity networks: Analysing the case for the US and EU supergrids. Energy Policy 2019, 135, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Human Rights and Capabilities. J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. The place of capability in a theory of justice. In Measuring Justice; Sen, A., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. Capabilities and Social Justice. Int. Stud. Rev. 2002, 4, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M. Beyond the social contract: Capabilities and global justice. Political Philos. Cosmop. 2005, 32, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.G. Mental wellbeing in the Anthropocene: Socio-ecological approaches to capability enhancement. Transcult. Psychiatry 2018, 57, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, B. Allocating the Earth; A Distributional Framework for Protecting Capabilities in Environmental Law and Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, H.; White, P. Society Actually does want Policies that Benefit Future Generations. The Conversation. 2017. Available online: https://in.news.yahoo.com/society-actually-does-want-policies-124841782.html?guccounter=1 (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- UK Parliament. Wellbeing of Future Generations (No2) Bill. House of Commons Session 2019–2021. Available online: https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/2736 (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Brown, L.; Mitchell, G.; Holden, J.; Folkard, A.; Wright, N.; Beharry-Borg, N.; Berry, G.; Brierley, B.; Chapman, P.; Clarke, S.; et al. Priority water research questions as determined by UK practitioners and policy makers☆. Sci. Total. Environ. 2010, 409, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, V. Infrastructural relations: Water, political power and the rise of a new ‘despotic regime’. Water Altern. 2016, 9, 292–318. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, T.; Priest, S. Partnership funding in flood risk management: New localism debate and policy in England. Area 2014, 46, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.S. Modernising Britain’s Victorian Infrastructure-an Engineering Opportunity; IET: Stevenage, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goytia, S.; Pettersson, M.; Schellenberger, T.; Van Doorn-Hoekveld, W.J.; Priest, S. Dealing with change and uncertainty within the regulatory frameworks for flood defense infrastructure in selected European countries. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, S.; Marvin, S. Managing water stress: The logic of demand side infrastructure planning. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1996, 39, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Deller, D.; Hviid, M. Price and Behavioural Signals to Encourage Household Water Conservation: Implications for the UK. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 33, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux-Hodgson, S.; Balmer, A.S. Synthetic biology, water industry and the performance of an innovation barrier. Sci. Public Policy 2013, 41, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotti, D.; Hyde, K.; Peña, D.O. Can water systems foster commoning practices? Analysing leverages for self-organization in urban water commons as social–ecological systems. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, V.L. Innovation in the water industry: Barriers and opportunities for US and UK utilities. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2015, 2, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J. Natural Flood Management: Assessing the Barriers to Wider Implementation; Nottingham Trent University: Ann Arbor, UK, 2019; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Broich, J. Engineering the Empire: British Water Supply Systems and Colonial Societies, 1850–1900. J. Br. Stud. 2007, 46, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijns, J.; Smith, H.M.; Brouwer, S.; Garnett, K.; Elelman, R.; Jeffrey, P. How Governance Regimes Shape the Implementation of Water Reuse Schemes. Water 2016, 8, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, V.; Baker, M. All hands to the pump? Collaborative capability in local infrastructure planning in the North West of England. Town Plan. Rev. 2014, 85, 753–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville-Shreeve, P.; Cotterill, S.; Grant, L.; Arahuetes, A.; Stovin, V.; Farmani, R.; Butler, D. State of SuDS delivery in the United Kingdom. Water Environ. J. 2017, 32, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrant, D.; Quinn, A.; Chapman, L.; Heaton, C. Water use of the UK thermal electricity generation fleet by 2050: Part 1 identifying the problem. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 844–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, G. Balancing flood risk and development in the flood plain: The Lower Thames Flood Risk Management Strategy. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2014, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, O.G. Waterworks and commemoration: Purity, rurality, and civic identity in Britain, 1880–1921. Contin. Chang. 2007, 22, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, L.; Macrorie, R.; Turner, A. Resource efficiency and the imagined public: Insights from cultural theory. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 34, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Isaac, R.; Walker, A. The key changes in PR19. Util. Week 2018, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.; Ashley, R.; Farrelly, M. Political and Professional Agency Entrapment: An Agenda for Urban Water Research. Water Resour. Manag. 2011, 25, 4037–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.L.; Jack, T.; Hitchings, R. ‘Already existing’ sustainability experiments: Lessons on water demand, cleanliness practices and climate adaptation from the UK camping music festival. Geoforum 2019, 103, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, S.; Warwick, F.; Lashford, C. Decision-Making and Sustainable Drainage: Design and Scale. Sustain. J. Rec. 2016, 8, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, D.; Raffin, M.; Jeffrey, P.; Smith, H. Collaboration on risk management: The governance of a non-potable water reuse scheme in London. J. Hydrol. 2019, 573, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekara, R.; Pecnik, G.; Girvan, M.; De La Rosa, T. Delivering integrated water management benefits: The North West Bicester development, UK. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Water Manag. 2018, 171, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heptonstall, J. Assessing flood risks for Goring and Streatley hydro. International Water Power Dam Constr. 2010, 62, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rodda, J.C. Sustaining water resources in South East England. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2006, 7, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, M.; McIntosh, B.S.; Seaton, R.A.; Jeffrey, P.J. An organisational innovation perspective on change in water and wastewater systems–the implementation of the Water Framework Directive in England and Wales. Urban Water J. 2012, 9, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.; Barr, S.; Butler, D.; Memon, F. Rainwater harvesting in the UK: Socio-technical theory and practice. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2012, 79, 1354–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.; Butler, D. Rainwater Harvesting and Social Networks: Visualising Interactions for Niche Governance, Resilience and Sustainability. Water 2016, 8, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.G.; Scarpa, R.; Acutt, M. Assessing water company customer preferences and willingness to pay for service improvements: A stated choice analysis. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankoff, G. The ’English Lowlands’ and the North Sea Basin System: A History of Shared Risk. Environ. Hist. 2013, 19, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millington, J. Powering the Water Industry; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tresidder, M.; White, P. Briefing: Design for manufacture and off-site construction at Woolston Wastewater Treatment Works (UK). Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Manag. Procure. Law 2018, 171, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. Cardiff Bay barrage: Management of groundwater issues. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Water Manag. 2008, 161, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, K. The “Commons” Versus the “Commodity”: Alter-globalization, Anti-privatization and the Human Right to Water in the Global South. Antipode 2007, 39, 430–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nations, U. The Human Right to Water and Sanitation, U.N.G.A.D.A.R. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, K. Worth the paper that they are written on? Human rights and the environment in the law of England and Wales. J. Hum. Rights Environ. 2010, 1, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrabin, R. Agriculture Bill: Soil at Heart of UK Farm Grant Revolution. 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-51128709 (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Ashley, R.; Lundy, L.; Ward, S.; Shaffer, P.; Walker, L.; Morgan, C.; Saul, A.; Wong, T.; Moore, S. Water-sensitive urban design: Opportunities for the UK. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2013, 166, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.R.; Keath, N.; Wong, T.H.F. Urban water management in cities: Historical, current and future regimes. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosnan, S. The Evolution of Justice. In Justice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).