Abstract

In contrast to shareholder-owned organizations, worker-owned cooperative organizations foster employee wellbeing such as employee satisfaction as an important outcome by itself. Due to expansions and economic fluctuations, larger worker-owned cooperations nowadays use mixtures of employment contracts resulting in varying shares of co-owners, contracted and temporary employees in workplaces. In the current paper, we research if this situation challenges the moral commitment of worker cooperatives to their employees, which derive from the cooperative philosophy on corporate responsibility. Where previous research contrasted employee wellbeing in worker cooperatives with share- holder owner organizations, this paper describes how various shares of co-owners in workplaces change mediating processes of helping climate and workplace participation and ultimately result in different levels of employee satisfaction. Archival data combined with survey data of 5907 employees in 99 hypermarkets were tested with multivariate analyses, and indicated that the helping climate and workplace participation positively mediated the association between the share of co-owners in hypermarkets and employee satisfaction. The findings imply that traditional worker-owned cooperatives, where a majority of all workers are owners, had more success in fostering cooperative values as a strategic outcome.

1. Introduction

Although employees are important stakeholders to organizations, their wellbeing is often only instrumental to achieve shareholder value. In alternative organizational forms such as worker-owned cooperative organizations, employee wellbeing, such as employee satisfaction, is an important goal by itself [1]. Employee co-operatives are labor owned and managed organizations, in which organizational resources and capabilities are put towards the pursuit of employee-owners’ common interests by means of institutionalized democratic processes [2]. The combination of financial ownership and democratic participation in management induces a long-term employee interest with the organization, resulting in positive attitudes such as employee involvement and satisfaction [3], and organizational performance [4,5].

International expansion and economic crises have lead employee-owned and managed organizations to become cautious about inviting new employee owners. To allow for workforce flexibility and faster expansion, larger cooperatives have been diversifying their employment strategies [6]. Today, employment arrangements in cooperative workplaces include waged labor and temporary contracts. In fact, under the umbrella of a co-operation such as Mondragon, workplaces have either full employee-ownership, ownership combined with a rink of waged and temporary workers, or solely waged and temporary workers. This situation challenges values of worker cooperatives such as self-help, democracy, and solidarity, which derive from the cooperative philosophy on corporate responsibility that stretches beyond the co-owners self-interest to the care for costumers and the wider local community [7]. However, employees in the flexible rink of a cooperative workplace enjoy less protection and employment benefits as compared to employee owners, a situation that is economically justified but clashes with cooperatives’ business ethics and corporate social responsibility [8]. The question is whether cooperative values can extend to workplaces with fewer or no employee-owners, and whether the same levels of employee satisfaction can exist in those workplaces.

Theoretical underpinning for this question turns our view to the group process literature. Building on workplace participation processes that generate satisfaction in employee-owned workplaces in general [9], we argue that some positive spillover will generate satisfaction for all employees, even when not all employees are owners, due to group processes that evoke positive social contagion [10], social learning [11] and social identity [12]. When small rates of waged and temporary employees work alongside a majority of employee-owners, the positive emotions can spill over to the entire workplace, but this effect may disappear at increasing rates of waged and temporary employees.

Workplace involvement includes engagement of employees in proactivity promoting behaviors in the workplace such as helping behavior and workplace participation [13]. Employee-ownership boosts workplace involvement, by (i) contributing to the formation of a helping climate in the workplace; in which employees support each other in day-to-day operational issues, and by (ii) facilitating workplace participation in idea sharing and making suggestions for improvement in the workplace [13,14]. In turn, these processes contribute to more satisfied employees in the workplace [15,16]. Employee satisfaction will benefit not only employees, but also the company because it increase the identification with company goals, the loyalty to the organization and the engagement in the work [17].

To our knowledge, there is no research taking a group dynamics view on the effects of workforce flexibility in labor-owned and managed workplaces and employee satisfaction. Authors such as Kasmir [8] warn that owners derive a favorite position at the expense of non-owners, which suggests a polarization in the workplace rather than spillover. On the other hand, it can be expected that cooperative company values stimulate a work culture that spills over to non-owners, and, consequently, create more job satisfaction to all employees. Qualitative evidence of initiatives to include temporary workers as good as can supports this line of reasoning [6]. However, the testing of group dynamic processes that explain potential spillover effects of employee ownership and its outcomes has been suggested but not been yet performed [18]. In this paper, we contribute to this gap by examining group processes of helping behavior and workplace participation in a sample of 99 cooperative workplaces with varying proportions of employee owners and waged or temporary employees. A workplace is an interdependent group of individuals working together in one location and who share a collective responsibility towards a performance output. In labor-owned and managed organizations where responsibility for decision-making are delegated at workplace level, this is the appropriate level of analysis. Following group dynamic theories such as emotional contagion [19], social cognition theory [20] and social identity theory [21], we can expect that when employees in workplaces work together, communicate and achieve results interactively, they influence each other in how they feel and behave. Reciprocal social interactions in workplaces result in shared attitudes and behaviors, which become a feature of the workplace [22].

Previously, effects of employee co-ownership have been studied at either on the organization level in contrast with capitalist organizations [23], or at the employee level and related to individual outcomes [24]. Research at the workplace adds to understanding group processes associated with changing proportions of employee co-ownership in workplaces.

1.1. Labor-Managed Co-Operatives and Employee Satisfaction

Employee satisfaction is an intrinsic goal of employee owned-and-managed organizations, and considered equally important as other performance goals. In this section, we briefly explain the nature of employee-owned and managed cooperatives, before we explain how the proportion of owners and flexible workers can erode workplace satisfaction. In alignment with Locke’s definition of individual job satisfaction [25], workplace satisfaction is defined as a shared positive emotional state resulting of the appraisal of job experiences in the workplace. Before theorizing the development of shared satisfaction in workplaces, this section presents the theory that explains how employees’ partaking in the ownership and management of the organization contributes to job satisfaction.

Employees’ partaking in employee-owned cooperatives exists of financial ownership and governance representation [4]. Financial ownership is regulated by for example collective incentive arrangements for profit sharing. Co-owners can exert influence through systems of representation, such as the election of representatives to governing councils, or inclusion of employee representatives on the organization’s board of directors [26]. Financial and governance involvement compose a bundle of co-ownership arrangements that shapes the basic rights of employee-owners [4]. Employee co-operatives institutionalize rights of employees as stakeholders of the organization. Due to expansions and economic crises, larger cooperatives also hire waged and temporary employees, who do not share in the financial gains of the organization, have limited say in the institutional governance of the workplace, and have lower job security [27].

Our first hypothesis builds on the assumption that co-ownership generally brings positive outcomes for individual workers [28,29]. Employee-owners contribute relatively small amounts of money to join the co-operative, and in return, they have control over the organization, employment security and incomes that are tied to the performance of the organization. A sense of control and security is crucial for generating satisfaction at work [30,31]. In result, this holds that employee-owners will have better conditions to experience job satisfaction as compared to waged and temporary employees. Since the jobs of waged and temporary employees are less secure [6], and allow for less to no democratic rights [8], waged and temporary employees will be less satisfied. If workplaces are viewed as a sum of individual employees, it can be expected that this reflect in the level of workplace satisfaction, such that workplaces with a larger share of co-owners will report higher levels of workplace satisfaction.

Hypothesis 1.

The share of co-owners is positively associated with workplace satisfaction.

However, workplaces outcomes are not just the sum of all individual outcomes. To understand the effects of different shares of co-owners, waged and temporary employees on workplace satisfaction, we need to include group dynamics processes.

1.2. The Share of Co-Owners and Collective Proactively Promoting Behaviors in the Workplace

Workplaces generate all kinds of group dynamics. Employees doing comparable work in a similar environment who frequently interact are aware of their mutual situation, and they will perceive and evaluate their work experiences in a similar way. Consequently, they will form work attitudes and behavior that are aligned with their coworkers [19,22]. In workplaces with only employee-owners, a particular group dynamic related to the ownership structure will develop. Formal employee co-ownership encourages employee-owners to experience psychological ownership of the organization [29], i.e., to perceive the co-operative organization as part of their extended selves. Such psychological ownership develops because it fulfills innate needs for self-identity, efficacy and motivation, and having a place to belong [32]. When experiencing such psychological ownership, employee-owners feel a bond with the organization, and this bond is expected to manifest itself in positive attitudes and behaviors, such as helping behavior [33,34].

Employees that work in a group that socially interact and are exposed to the same structures, processes and behaviors develop a workplace climate [35,36]. In a cooperative workplace where employee-owners work together, a facet-specific work helping climate develops through the shared values of the cooperative, where helping each other is accepted and expected [15,37].

When workplaces exist of large shares employee-owners and small shares of waged or temporary employees, positive promoting behavior will still happen, due to processes of emotional contagion [10,19] and social learning [11]. In workplaces with a majority of employee owners, the dominant behavioral norm will be ‘helping each other’, because that is at the core of the cooperative values. Through social interaction, employee-owners will induce a positive emotional contagion existing of psychological ownership resulting in more helping behavior [10,19]. In addition, role modelling by employee-owners by showing proactive helping behavior provides social learning to non-owners who will mimic the dominant group behavior. This will build and preserve a supportive and cooperative work setting [11,22].

However, in workplaces with a mixed composition, or a majority of waged and temporary employees, a number of issues threaten these positive group dynamics. In mixed groups with smaller shares of employee-owners, it is more difficult for the employee owners to interact with all non-owners, which reduces the chance of social learning and social influence. The group of owners in mixed workplaces becomes too small to spread the positive emotions associated with ownership. Moreover, mixed groups can lead to in-group and outgroup formation, which can lead to feelings of exclusion and dissatisfaction [12,38]. Non-owners may feel excluded and dissatisfied, because of perceived privileges of a small group of owners. This sub-group formation will hinder social learning form outgroups, and lead non-owners to feel a lesser bond with the organization and it cooperative values, and consequently, to engage in helping behavior. To demonstrate emotional contagion of a helping behavior from employee owners to waged and temporary workers, we propose that non-owners’ perception of collective helping behavior in the workplace relates to the proportion of owners in their workplace.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Non-co-owners in the workplace perceive more collective helping behavior in workplaces with larger shares of co-owners.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

The shares of co-owners is positively associated with the level of helping climate.

For workplaces as a whole, this will lead to a positive association between the proportion of co-owners and the helping climate in a workplace.

In addition to encouraging helping behavior, psychologically experienced ownership elicits expectations with regard to rights on information and participation in decision-making [18,29,32]. Given that, group-level climates at work have a particularly strong effect on the behavior of the group [35] we suggest that the combination of participation expectations with a strong helping climate leads to more active and responsible collective participation behavior in the workplace. Workplace participation is defined, as “shared promoting behaviors aimed at improving the work and work conditions” [13] (p. 109). In particular, it is likely that more workers will speak up when they believe that others support their position, as will be the case in a strong helping climate [16,39]. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3.

The level of helping climate is positively associated with workplace participation.

1.3. Workplace Participation and Collective Worker Satisfaction

Employee participation in decision-making is a central feature of High Performance and High Involvement Work Systems (HIWS) [40]. Engaging in workplace participation provides employees with the opportunity to participate in diagnosing and resolving problems related to workplace issues, but also to relate to more strategic and organization-wide issues, which will lead to management decisions that are supported by employees [41]. Workplace participation is an important condition for employee satisfaction, because it provides employees with valuable resources allowing them to feel empowered [42], to feel enabled in achieving work goals [43]. According to the social exchange theory and its extensions [44,45,46], employees are likely to reciprocate these advantages by developing higher levels of satisfaction. Research evidence confirms that participation is beneficial for individual employee satisfaction [16,47], as well as for group level satisfaction [31].

Based on these arguments, we propose:

Hypothesis 4.

Workplace participation is positively associated with workplace worker satisfaction.

In sum, the share of co-owners in a workplace is expected to positively influence workplace worker satisfaction. This relationship is explained through social processes within the workplace. A larger share of co-owners in a workplace induces specific social dynamics—and particularly, a helping climate—that create a stimulating environment for providing ideas for improvement. As a result, the quality of managerial decisions is enhanced, which contributes to satisfaction in the workplace. Previous research confirmed a positive mediated process for employee ownership to job satisfaction at the level of individual employees, mediated by perceived participation [16]. Following the logic of group dynamics described earlier, we propose that a helping climate and workplace participation sequentially mediate the relationship between the share of co-owners and workplace satisfaction. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5.

The indirect association between share of co-owners and workplace worker satisfaction will be sequentially mediated by the levels of helping climate and workplace participation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

The data for this research were obtained in 2011 from one of the businesses of a large co-operative retail chain in Spain. This specific business consists of 105 hypermarkets (large shops selling food and non-food products), which collectively employ around 10,000 people (one-fourth of all employees of the whole retail chain) [2,48]. Co-owners of the company participate financially in the organization (full collective financial co-ownership) [4]. In order to become a co-owner, workers have to pay an entrance fee. Alongside their monthly wages, co-owners receive dividends corresponding to their share in the profits or losses of the organization [48]. The enactment of co-ownership within the co-operative is organized in a system of representatives, who are elected to the co-operative’s governing bodies on the principle of ‘one member, one vote’. The central governing council (at the level of the retail chain) exists of employee representatives and consumer representatives (50% each), whom do employee co-owners and consumer members at the general assembly elect, respectively. The governing council appoints the general manager, who in turn appoints the managing directors of the hypermarkets. Co-owners also choose representatives for their own hypermarket. These representatives are responsible for social issues within the hypermarket and discuss day-to-day operations with the manager of the hypermarket on a monthly base.

All employees of the group of hypermarkets were asked to complete a questionnaire with confidentiality guaranteed by the researchers. Respondents were informed in general terms that the goal of the study was to examine diverse issues in the workplace, and best practices. The survey took place at the workplace during working hours. At the time of administering the survey, we also obtained administrative data from each hypermarket to determine how many of its employees also were co-owners. After a period of two weeks, the questionnaires were collected from each hypermarket and sent to an external company to be digitized. This company subsequently provided us with an Excel file containing all the responses for each hypermarket.

Survey data of 6091 co-owners and contract employees of all 105 hypermarkets were collected measure helping climate, workplace participation, and workplace worker satisfaction. We excluded 184 observations from the analyses due to missing values on the co-ownership, resulting in a sample comprising 5907 respondents working in 99 different hypermarkets (response rate 59%). On average, 60 respondents per hypermarket were included in the study (range 21–148). The share of co-owners per hypermarket ranged from none (no co-owners) to all (only co-owners). Among respondents, 72% were co-owners of the co-operative and 28% were contract employees (15% with a fixed contract and 13% with a temporary contract); 20% of the employees were male, 64% had tenure between 3 and 15 years, and almost 9% held an operational management position

2.2. Measures

The survey data contained a number of items that were assessed at the individual level. Because we were interested in within-group agreement (helping climate, workplace participation and workplace worker satisfaction in each hypermarket), for each variable, we calculated within-group agreement (rwg) to justify aggregating the individual scores to the group level [49]. As suggested by James [50] we use a cutoff value of 0.70. We also estimated group-level internal consistencies by using the average item score per group [51]. In addition, we calculated intra-class correlations (ICCs), and tested whether average scores differed significantly across the different hypermarkets (indicated by F values); ICC1 denotes the individual-level variance that can be explained by group membership, and ICC2 denotes the reliability of group means [52]. The recommended cutoff value for ICC2 is 0.60 [53]. Taken together, these agreement statistics empirically justify examining this construct at the workplace.

Collective helping behavior and helping climate. We used the same measure to assess collective helping behavior (individual participants’ perceptions) as well as helping climate (group-level perceptions, i.e., the shared perceptions of co-workers working in the same hypermarket) regarding the shared affiliative and cooperative behavior among co-workers in the workplace. Based on the direct consensus composition model, we assume that the conceptualization and operationalization at the lower level is functionally isomorphic to another form of the construct at the higher level [54], i.e., helping climate is functionally similar to the individual construct collective helping behavior. Collective helping behavior and helping climate were measured with the following three items, to which participants responded by rating a 6-point Likert scale: ‘In my workplace we are willing to help co-workers solve work-related problems’, ‘In my work-place we communicate frequently and exchange information freely’, and ‘Peer support is common in my workplace’. This operationalization of helping is in line with prior research on work-related helping behavior in the workplace [13,55]. Cronbach’s alpha of collective helping behavior was 0.87.

As elaborated above, a helping climate is a work climate were employees facilitate each other in day-to-day operations, by providing efforts and resources and to their co-workers [13,14]. A higher group score on the items presented above reflected a stronger helping climate. Cronbach’s alpha, at the group level, was 0.94, rwg was 0.86, and ICC1 and ICC2 were 0.06 and 0.80 (F (98, 5841) = 4.98, p ≤ 0.01), respectively. These results justify aggregating the individual scores to the workplace, meaning that we can assume that a higher group score reflects a stronger helping climate.

Workplace participation. In our context, workplace participation refers to the joint opportunity of co-workers working in the same hypermarket (workplace) to put forward suggestions for change and ideas for innovations [13]. Workplace participation (i.e., co-workers share similar higher or lower levels of individual-level participation) was measured using three items based on the employee participation scale of Delery and Doty [56]. These items reflect the degree to which employees were allowed to have input into the targets, business plan, and the future of their hypermarket. The items were ‘I participate in deciding on the annual targets for my workplace’, ‘I participate in the definition, control and monitoring of the business plan on an annual basis’, and ‘I have the opportunity to participate in important decisions about the future of my workplace’. These items were measured on a 6-point Likert scale. The group-level internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha at the group-level) was 0.93 and rwg was 0.83. Similarly, ICC1 and ICC2 were 0.08 and 0.84, respectively (F (98, 5841) = 6.14; p ≤ 0.01). The same as with the helping climate, these results indicate that aggregation was appropriate, and that a higher group score indicates a greater extent of workplace participation.

Workplace satisfaction. Workplace satisfaction is defined as a workplace’s shared satisfaction, i.e., employees share similar levels of individual-level satisfaction. Satisfaction was first assessed at the individual level of analysis using the 3-item measure developed by Hart, Griffin, Wearing, and Cooper [57]. An example item is, ‘Overall, I am satisfied with my job’. The three items were each rated on a 6-point Likert scale, and had a group-level Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90, and an rwg index of 0.79. ICC1 was 0.06, and ICC2 was 0.79 (F (98, 5841) = 4.73, p ≤ 0.01), which justified aggregating the individual scores to the workplace to measure workplace worker satisfaction.

Share of co-owners. As noted above, the share of co-owners in each hypermarket was obtained from administrative data from each hypermarket at the time of the survey. This measure reflects the percentage of workers per hypermarket (out of all employees of that hypermarket) who participate financially in the organization, and whose voice is heard through a system of representatives (as opposed to employees whose employment is based on a regular contract). Values ranged from zero (no co-owners), to 100% (all co-owners).

Control variables. We controlled for workplace size (number of workers per workplace (hypermarket), based on the information in the company records. Furthermore, we controlled for average job grade within the workplace (ranging from 1 = lowest to 5 = highest job level within the hypermarket). The included these controls because these features may affect participation [58] and satisfaction [59]. Moreover, to rule out the possibility that workplace participation is a substitute for lack of leadership, we added teams’ perception of leadership, measured with the ‘Leadership Vision’ subscale of the transformational leadership scale of Rafferty and Griffin [60] as a control variable. An example item of the three-item subscale is, ‘Has a clear understanding of where he/she wants our workplace to be in 5 years’. The three items regarding leadership perception were each rated on 6-point Likert scale and had a group-level Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 and an rwg index of 0.78. ICC1 was 0.05 and ICC2 was 0.77 (F (98, 5841) = 4.26, p ≤ 0.01), which justified aggregating the individual scores to the workplace.

2.3. Analyses

Hypothesis 2a was the only hypothesis that referred to individual-level (as opposed to group-level) outcomes, namely, the effect of share of co-owners in a workplace on non-co-owners’ perception of collective helping behavior. To test this hypothesis, we used ANOVAs to compare non-co-owners’ perception of collective helping behavior across work-places with co-ownership shares of (i) less than 50% (18 workplaces), (ii) between 50% and 80% (33 workplaces), and (iii) more than 80% (43 work-places). The other hypotheses were tested (on the group level) with regression analysis using the Hayes PROCESS method in SPSS [61]. This method has the advantage that it can provides tests of total and specific indirect effects, which suits the proposed model with a double mediation [62]. First, we examined the direct effects: of the share of co-owners in the workplace on workplace satisfaction (Hypothesis 1), and on helping climate (Hypothesis 2b); of helping climate on workplace participation (Hypothesis 3); and of workplace participation on workplace satisfaction (Hypothesis 4). Furthermore, to examine the mediating roles of helping climate and workplace participation in the indirect relationships between share of co-owners and workplace satisfaction (Hypothesis 5), we applied the procedure suggested by MacKinnon, Fairchild, and Fritz [63], using boot-strapping [64].

3. Results

Means, standard deviations and correlations among the variables are displayed in Table 1. Bivariate correlations show that the share of co-owners per hypermarket is not significant associated with workplace satisfaction (r = 0.01, n.s.). Workplace participation was found to be positively with workplace satisfaction (r = 0.74, p < 0.01). Table 1 also indicates that the share of co-owners per hypermarket is positively associated with work-place participation (r = 0.21, p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations and correlations between the study variables.

ANOVAs (F(5875,5) = 9.48, p ≤ 0.01) indicated that non-co-owners in hypermarkets with more than 80% co-owners perceived significantly more collective helping behavior compared with non-co-owners in hypermarkets with 50–80% co-owners (ΔM = 0.09, p ≤ 0.01) or in hypermarkets with less than 50% co-owners (ΔM = 0.27, p ≤ 0.01). Similarly, non-co-owners in hypermarkets with co-ownership shares of 50–80% perceived more collective helping behavior compared with non-co-owners in hypermarkets with less than 50% co-owners (ΔM = 0.18, p ≤ 0.01). This confirmed Hypothesis 2a.

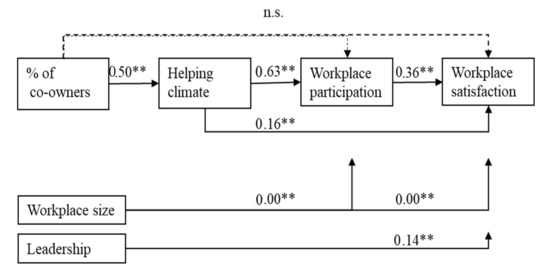

Regression analyses in which workplace satisfaction was the dependent variable showed that the share of co-owners per hypermarket did not directly relate to workplace satisfaction (Table 2, Model 3, B = −0.07, s.e. = 0.06, n.s.), thereby refuting Hypothesis 1a. They further showed that, in accordance with Hypothesis 2b, a higher share of co-owners was associated with higher levels of perceived helping climate (Table 2, Model 1, B = 0.50, s.e. = 0.11, p ≤ 0.01). In line with Hypothesis 3, a stronger perceived helping climate related to more workplace participation (Table 2, Model 2, B = 0.63, s.e. = 0.09, p ≤ 0.01), which resulted in more workplace satisfaction (Table 2, Model 3, B = 0.36, s.e. = 0.06, p ≤ 0.01). This implies that Hypothesis 4a is supported. Following procedures discussed by MacKinnon et al. [63] and in accordance with Hypothesis 5, we confirmed that helping climate and workplace participation mediated the association be-tween the share of co-owners and workplace satisfaction. Table 2 shows that the bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (CI) around the unstandardized indirect effects of the model comprising share of co-owners–helping climate–workplace participation–workplace satisfaction did not include zero (Table 2, B = 0.11, s.e. = 0.03, bootstrap 95% CI, 0.06, 0.20), thus supporting the mediation effect. Figure 1 visualizes the findings of the sequential mediation model.

Table 2.

Conditional direct and indirect effects of share of co-owners on workplace satisfaction, mediated by helping climate and workplace participation.

Figure 1.

Sequential mediation model of share of co-owners, helping climate, workplace participation and workplace satisfaction. Note: ** = p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

During expansions and economic crises, worker cooperatives introduced new forms of employment relations such as waged and temporary employees, leading to critical questions whether cooperative values can bring positive attitudes and behavior to all employees, even in workplaces with fewer or no employee-owners [8]. The results indicate that positive attitudes and behaviors that are associated with cooperative values indeed decrease when the proportion of employee owners reduce and more waged and temporary employees are hired. The findings indicate an indirect effect of the proportion of employee owners on workplace satisfaction, which is mediated by helping climate and workplace participation. The paper is the first to take a group level view on processes explaining how employee ownership enhances satisfaction.

The sequential mediation suggest that in workplaces with more employee owners, cooperative values are reinforced in the daily interactions between employees. Ownership provides employees with a formal say and responsibility in management, which translates to psychological ownership needed to engage in supportive attitudes and behaviors [29], which in turn enhance satisfaction. These results show empirical evidence of the effect of group dynamic processes in co-operations, where employee co-ownership stimulates a workplace climate and behavior that spills over to non-owners.

The absence of a direct relationship between the share of co-owners and workplace satisfaction can be explained by the distal nature of a representative voice system [16]. Daily interactions with colleagues, management and customers in the workplace exert more influence on a worker’s wellbeing than the incidental occasions when they can formally express their voice by voting. In order for a representative voice system to increase satisfaction, workers have to perceive the actual practices that tie the co-ownership system of representatives to workplace participation and helping [65]. This happens in the current research as well.

Critics have warned for the risk of degeneration in employee owned and managed organizations [66]. This means that after the initial shared enthusiasm about employee involvement in the cooperative, economic challenges and organizational politics will lead the organization to behave similar to any capitalistic organization, with less moral commitment to the employees and a disappointed workforce as a result. Clearly, cooperatives struggle with keeping cooperative values alive [2]. The findings of the current research back the degeneration warning and underline the need for strategies to actively promote and manage cooperative values, and to preserve caring (business) relationships in cooperative workplaces [66,67]. However, there is some proof for positive contagion of cooperative values expressed in a helping climate in workplaces with a small number of waged and temporary employees. As the findings for Hypothesis 2a illustrate and in line with organization contagion theory [19], there is a spillover of perceived helping climate between co-owner employees and non-owners. This means that non-owners can experience cooperative values and care ethics, just by working alongside employee-owners. The findings also indicate that this effect quickly fades when the proportion of owners in a workplace diminishes.

The interplay of structural differences between employees and group processes is related to social identity processes (e.g., [38]) and addresses the question of the tipping point of positive emotional contagion. In the current paper, we clustered three levels of ownership proportions, ranging from less than half, to 50–80 percent, to more than 80 percent. Given the significant differences between these proportional levels, the question becomes pressing as to where the precise tipping point lies [19]. Future research could do a more fine-grained examination of the tipping point where the proportion of owners, waged and temporary employees turns disadvantageous in regards to perceptions of helping climate, participation and job satisfaction.

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

Although the research was carefully designed, several limitations should be taken into account. First, the research was conducted in a single chain of hypermarkets in a single country. Since the context in which employee ownership operates may substantially influence its effectiveness, the capacity to generalize our findings to other sectors or countries may be limited. Nevertheless, a number of studies, which use individual employee data, found in various contexts and countries support for the positive association between employee co-ownership and satisfaction. For example, a study in a media and communications firm in the USA found that perceived influence from employee co-ownership was positively related to job satisfaction [68]. Moreover, employee satisfaction increased when co-ownership was combined with employee participation in a study in four UK bus companies [9]. Second, the variety of employee participation structures, both in co-operatives and in traditional organizations, is larger than the participation types included in this research [4].

Third, it is not possible to establish causality with regard to the effects of helping and participation on satisfaction, as data for the latter three variables were collected at a single point in time. This implies that satisfaction might have influenced employees’ perceptions of helping climate and workplace participation, rather than the other way around. Though causal relationships between helping climate and workplace participation and between workplace participation and workplace satisfaction have been established in the literature [39], longitudinal research is needed to further investigate the possibility of reverse causation in the helping cli-mate-workplace participation-satisfaction linkage. Further longitudinal research could also rule out the possibility that common method variance (CMV) played a role in our results. However, Spector [69] suggests that small to moderate inter-construct correlations—such as those presented in the findings (moderate individual-level correlations ranging from 0.40 to 0.42)—can counter the idea that CMV is a universal inflator of correlation.

4.2. Practical Implications

The results of this research suggest that cooperative workplaces have difficulty maintaining employee satisfaction when more waged and temporary employees work in a workplace. However, at small numbers of non-owners, the cooperative values of helping and participating can still be shared. The first practical implication is that cooperatives need to put limits to the number of waged and temporary employees. Moreover, waged and temporary employees need additional explanation of cooperative vision and their contribution, and a window of opportunity for their rights to become an owner. Revitalizing the vision and values of the cooperative is conditional for supportive attitudes and behaviors.

5. Conclusions

Co-operatives have gained renewed attention as an organizational form that places equal importance on societal impact as economic performance. A key contribution of the current study lies in the scale on which workplace proportions of co-ownership could be related to employee reports on helping climate, participation and satisfaction. The paper supports that purer forms of employee cooperatives are most successful in achieving their societal impact objectives in terms of employee satisfaction.

Author Contributions

All authors substantially contributed to the conceptualization; methodology; validation; formal analysis; investigation; resources; data curation; writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing; visualization; supervision, and project administration of the research and research article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Review Board of Tilburg University (code RP492).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data was obtained from a co-operative retail chain and are available on request from the corresponding author with the permission of the retail chain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cheney, G.; Cruz, I.S.; Peredo, A.M.; Nazareno, E. Worker cooperatives as an organizational alternative: Challenges, achievements and promise in business governance and ownership. Organization 2014, 21, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J.; Basterretxea, I.; Salaman, G. Managing and resisting ‘degeneration’ in employee-owned businesses: A comparative study of two large retailers in Spain and the United Kingdom. Organization 2014, 21, 626–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, I.; Suseno, Y.; Pinnington, A.; Money, A. The influence of financial participation and participation in decision-making on employee job attitudes. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 15, 587–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ner, A.; Jones, D.C. Employee Participation, Ownership, and Productivity: A Theoretical Framework. Ind. Relat. A J. Econ. Soc. 1995, 34, 532–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, A.; Robinson, A. Employee Stock Ownership, Involvement, and Productivity: An Interaction-Based Approach. ILR Rev. 2010, 64, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errasti, A.; Mendizabal, A. The Impact of Globalisation and Relocation Strategies in Large Cooperatives: The Case of the Mondragón Cooperative Fagor Electrodomésticos S. Coop. Adv. Econ. Anal. Particip. Labor Manag. Firms 2007, 10, 265–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdín, G.; Dean, A. Revisiting the objectives of worker-managed firms: An empirical assessment. Econ. Syst. 2012, 36, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasmir, S. The Mondragon Cooperatives and Global Capitalism. New Labor Forum 2015, 25, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, A.; Wilson, N.; Wright, M. The Perception and Effects of Share Ownership: Empirical Evidence from Employee Buy-Outs. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 1998, 36, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S.G. The Ripple Effect: Emotional Contagion and Its Influence on Group Behavior. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Model of Causality in Social Learning Theory. In Cognition and Psychotherapy; Mahoney, M.J., Freeman, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, G. Social Identity Theory. Encycl. Crit. Psychol. 2014, 1781–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L.; Lepine, J.A. Helping and Voice Extra-Role Behaviors: Evidence of Construct and Predictive Validity. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhao, H.H.; Walter, S.L.; Zhang, X.-A.; Yu, J. Achieving more with less: Extra milers’ behavioral influences in teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1025–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, W.G.; Unterrainer, C.; Schmid, B.E. The influence of organizational democracy on employees’ socio-moral climate and prosocial behavioral orientations. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 1127–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.G.; Unterrainer, C.; Höge, T. Psychological Research on Organisational Democracy: A Meta-Analysis of Individual, Organisational, and Societal Outcomes. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 69, 1009–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrwa, J.; Kaźmierczyk, J. Conceptualizing Job Satisfaction and Its Determinants: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 21, 138–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, S.; Tian, A.W.; Newman, A.; Martin, A. Psychological ownership: A review and research agenda. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S.G.; Coutifaris, C.G.; Pillemer, J. Emotional contagion in organizational life. Res. Organ. Behav. 2018, 38, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Hofmann, D.A. The Structure and Function of Collective Constructs: Implications for Multilevel Research and Theory Development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logue, J.; Yates, J.S. Cooperatives, Worker-Owned Enterprises, Productivity and the International Labor Organization. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2006, 27, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, D.; Freeman, R.; Blasi, J. Do Workers Gain by Sharing? Employee Outcomes under Employee Ownership, Profit Sharing, and Broad-Based Stock Options. In NBER Working Paper Series. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w14233 (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Locke, E.A. What is job satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1969, 4, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.; Cheney, G. Worker-owned-and-governed co-operatives and the wider co-operative movement. In The Routledge Companion to Alternative Organization, 1st ed.; Parker, M., Cheney, G., Fournier, V., Land, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 64–89. ISBN 9780415782265. [Google Scholar]

- Burdín, G.; Dean, A. New evidence on wages and employment in worker cooperatives compared with capitalist firms. J. Comp. Econ. 2009, 37, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, A. Employee Ownership Participation and Governance: A Study of ESOPS in the UK 2001, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 9781138863965. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J.L.; Kostova, T.; Dirks, K.T. Toward a Theory of Psychological Ownership in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczyńska, A.; Batorski, D.; Sellens, J.T. Employment Flexibility and Job Security as Determinants of Job Satisfaction: The Case of Polish Knowledge Workers. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 126, 633–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatzick, C.D.; Iverson, R.D. Putting employee involvement in context: A cross-level model examining job satisfaction and absenteeism in high-involvement work systems. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 3462–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Rodgers, L. The Psychology of Ownership and Worker-Owner Productivity. Group Organ. Manag. 2004, 29, 588–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Crossley, C.D.; Luthans, F. Psychological ownership: Theoretical extensions, measurement and relation to work outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Kostova, T.; Dirks, K.T. The State of Psychological Ownership: Integrating and Extending a Century of Research. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2003, 7, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzi, M.; Schminke, M. Assembling Fragments into a Lens: A Review, Critique, and Proposed Research Agenda for the Organizational Work Climate Literature. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 634–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Ehrhart, M.G.; Macey, W.H. Organizational Climate and Culture. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; González-Romá, V.; Ostroff, C.; West, M.A. Organizational climate and culture: Reflections on the history of the constructs in the Journal of Applied Psychology. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, M.A.; Terry, D.I. Social Identity and Self-Categorization Processes in Organizational Contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhart, M.G.; Naumann, S.E. Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Work Groups: A Group Norms Approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 960–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boxall, P.; Macky, K. Research and theory on high-performance work systems: Progressing the high-involvement stream. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2009, 19, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Zagelmeyer, S.; Marchington, M. Embedding employee involvement and participation at work. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2006, 16, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.J.; Wall, T.D. Work enrichment and employee voice in human resource management-performance studies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1335–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964; ISBN 978-0-88738-628-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner, A.W. The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, M.D.; Mellizo, P. The relative effect of voice, autonomy, and the wage on satisfaction with work. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 1186–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcadell, F.J. Democracy, Cooperation and Business Success: The Case of Mondragon Corporacion Cooperativa. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 56, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R.; Demaree, R.G.; Wolf, G. Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R. Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1982, 67, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Mathieu, J.E.; Bliese, P.D. A Framework for Conducting Multi-Level Construct Validation. Res. Multi-Level Issues 2004, 3, 273–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bliese, P.D. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations. Foundations, Extensions and New Directions, 1st ed.; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 349–381. ISBN 0787952281. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, W.H. Conceptualizing and Measuring Organizational and Psychological Climate: Pitfalls in Multilevel Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K.; Kozlowski, S.W. Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 0787952281. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman, R.H.; Blakely, G.L. Individualism-collectivism as an individual difference predictor of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delery, J.E.; Doty, D.H. Modes of Theorizing in Strategic Human Resource Management: Tests of Universalistic, Contingency, and Configurations. Performance Predictions. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 802–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.M.; Griffin, M.A.; Wearing, A.J.; Cooper, C.L. Manual for the QPASS Survey; Public Sector Management Commission: Brisbane, AU, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, E.W. Employee Voice Behavior: Integration and Directions for Future Research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J. Unit Size, Work Experiences and Satisfactions: An Exploratory Study. Psychol. Rep. 1996, 78, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, A.E.; Griffin, M.A. Dimensions of transformational leadership: Conceptual and empirical extensions. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J.; Fritz, M.S. Mediation Analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Nishii, L.H. Strategic Hrm and Organizational Behavior: Integrating Multiple Levels of Analysis; CAHRS Working Paper; Cornell University ILR School: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2007; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1813/77351 (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Sauser, W.I. Sustaining Employee Owned Companies: Seven Recommendations. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 84, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxley, J.; Wittkower, D.E. Care and Loyalty in the Workplace. Appl. Care Ethics Bus. 2011, 33, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchko, A.A. The Effects of Employee Ownership on Employee Attitudes: An Integrated Causal Model and Path Analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 1993, 30, 633–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Method Variance in Organizational Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2006, 9, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).