Abstract

In Romania, there is an emerging market of dairy products delivered through short food supply chains. Although this distribution system has existed since the communist period, and even though more than three decades have passed since then, the market fails to be mature, subject to taxation, or achieve a high diversity in terms of dairy categories, with a consolidated marketing culture that has significant effects on the regional socio-economic environment. The aim of this study was to observe whether the Corona Virus Disease of 2019 (COVID-19) crisis has influenced consumer behavior regarding dairy products delivered directly from producers in Suceava County, Romania. The research is based on a survey conducted between April and May, 2020, and the analysis relies on both quantitative and qualitative methods (namely, anthropological and ethnographic). From the provided responses, it a change was observed in the future buying behavior on short food supply chains, in a positive sense. One of the key findings was that family represents the main environment for passing on the values that influence the buying behavior. Another key finding was that the behavioral changes on the short food supply chains exert pressure on their digital transformations.

1. Introduction

Healthy and sustainable food is one of the most important challenges the modern human is facing currently [1]. Quality of life and environmental protection are increasingly reflected in consumer concerns, influencing purchasing behavior. During major health crises, purchasing behavior can be threatened as epidemics and pandemics have always had negative effects on food production, distribution chains, and food consumption [2,3,4,5,6]. At present, humanity is facing a new health crisis, the Corona Virus Disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which has direct effects on food security, especially for the financially disadvantaged people or populations [7,8,9,10].

Food systems are defined as the sum of actors (farmers, processors, traders, consumers, etc.), and their interactions along the various stages of the food value chain, such as production, storage, processing, transportation, distribution, etc. [11]. The COVID-19 pandemic has particularly affected these interactions.

A challenge in the short term will be to match short food supply chains with local demand and consumer needs [12]. An interesting point of discussion would be to scale-up the urban farming to reduce food-miles and to increase accessibility and resilience of urban production [12].

Changing consumption patterns increases stock in retail chains [13], but also at the consumer level, changing the share of commodities like fresh food, exponential growth in online deliveries, restrictions on the movement of goods [14], insufficient labor due to border closures, syncopes in the agro-industrial processing sector, the closure of the economic agents from HORECA, but also of the schools, restaurants, and catering services, are the main problems generated by this crisis in agriculture in most European countries.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) argues that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly influenced the short food supply food chains (SFSCs) in terms of both supply and demand [15]. The dairy subsector, an important segment of the global economy, has also been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly due to the measures taken at the local or regional level to protect the population. However, world milk production has demonstrated resilience so far, and there are indicators showing a slight increase in 2020 [16].

The aim of the present study was to analyze the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the buying behavior of dairy products purchased directly from producers in Suceava County of Romania during the state of emergency (16 March–15 May 2020). The goal was to observe whether the COVID-19 crisis has influenced the consumers’ behavior regarding dairy products delivered directly from producers in Suceava County, Romania. The research is based on a survey conducted in the first quarantined area from Romania, and the analysis relies on both quantitative and qualitative methods (namely, anthropological and ethnographic).

1.1. Suceava County during COVID-19

Suceava County is situated in the North-Eastern part of Romania, on the border with Ukraine, and it is the second-largest county in Romania with an area of 8553.5 square kilometers [17]. On the 1 January 2020, 764,123 people (3.44% of Romania’s population) resided in Suceava County, out of which approximately 44% lived in an urban area (5 municipalities and 11 cities) and 56% lived in a rural area (98 municipalities). The distribution of the population by age categories, expressed as a percentage, is as follows: 22% of the population is under 19 years old, 22% is between 19 and 34 years old, 23% is between 35 and 49 years old, 18% is between 50 and 64 years old, and 15% is over 65. Therefore, nearly 62% of the population falls into the category of active population (20–64 years old) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The population of Suceava County compared to the total Romanian population.

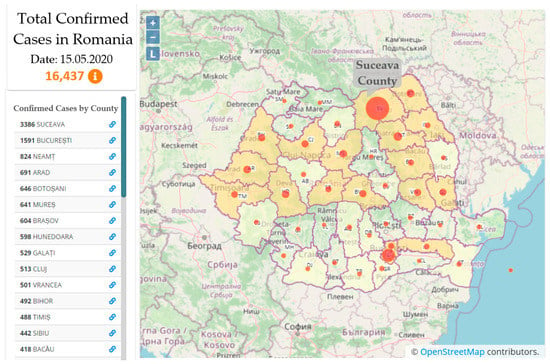

In Romania, the COVID-19 pandemic manifested itself most intensely in Suceava County (Figure 1), with an exponential increase in the number of confirmed cases, reaching 3386 cases on 15 May 2020, which represents 20.6% of the total cases per country.

Figure 1.

Location of Suceava County in Romania and the number of active cases at the national level on 15 March 2020. Images processed by authors and reproduced with permission from Geo-spatial.org (accessed on 11 March 2021) [18].

During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, part of the population of Suceava County (Suceava municipality and neighboring communes) was quarantined, under the effect of military ordinances issued by the Government of Romania [19]. During that period, important changes in terms of human mobility took place in Romania as follows: visits to shops and other leisure trips decreased by over 85%, going shopping decreased by 65%, travel to work decreased by over 48%, while remaining in residential space increased by more than 17% [20]. On 15 May 2020, the state of emergency in Romania was formally terminated, and the state of alert was established. The quarantine in Suceava County ceased at the same date, and this measure relaxed the activity and mobility of the population [21].

Table 2.

Socio-demographic profile of respondents.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic profile of respondents.

| Gender | Frequency | Valid Percent |

| Female | 274 | 61.3 |

| Male | 173 | 38.7 |

| Total | 447 | 100.0 |

| Age range | Frequency | Valid Percent |

| 19–34 | 138 | 30.9 |

| 35–49 | 204 | 45.6 |

| 50–64 | 87 | 19.5 |

| Over 65 | 18 | 4.0 |

| Total | 447 | 100.0 |

| Marital status | Frequency | Valid Percent |

| Married | 338 | 75.6 |

| Single | 109 | 24.4 |

| Total | 447 | 100.0 |

| People in your household | Frequency | Valid Percent |

| 1 | 30 | 6.7 |

| 2 | 120 | 26.8 |

| 3 | 133 | 29.8 |

| 4 | 121 | 27.1 |

| 5 | 33 | 7.4 |

| 6 | 6 | 1.3 |

| 7 | 4 | 0.9 |

| Total | 447 | 100.0 |

| Education | Frequency | Valid Percent |

| Middle School | 10 | 2.2 |

| High School | 43 | 9.6 |

| Bachelor‘s Degree | 220 | 49.2 |

| Master’s Degree | 157 | 35.1 |

| PhD | 17 | 3.8 |

| Total | 447 | 100.0 |

Suceava County was chosen as a study area for several reasons. Firstly, it was the most affected county in Romania, with the highest number of confirmed cases at the beginning of the pandemic. Secondly, Suceava city and its neighboring localities were the first quarantined in Romania. The fact that Suceava is a county with a rich tradition both in animal husbandry and preparation of dairy products was also an important factor. At the same time, Suceava has a special status in the North-East Development Region of Romania [23] from a socio-economic point of view, by contributing to the creation of regional and national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and by the increased volume of remittances [24,25].

1.2. The Importance of Milk and Dairy Products in the Human Diet and Global Food System

Milk is generally acknowledged as a complete food that contains all the nutritional principles necessary for life, which is why it has been used by humans as food since time immemorial [26]. Due to this perception of a complete food product, milk has acquired a strong cultural imprint in the symbolic system of health [27,28]. As early as 1939, in the February issue of the Milk Magazine, it was mentioned the importance of milk: “This precious food must not be missing from the table of any good household” [29].

Dairy products have always had an important economic value, and this has led to a steady increase in production. According to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)-Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) forecasts, world milk production will increase by 177 million tons by 2025 as compared to the level recorded in 2016 [30], and this increase will influence the long-term economic sustainability, farm efficiency, labor market, environment, and consumer society [31,32].

At the same time, dairying supports livelihoods. Publicly acknowledged by FAO, dairy animals are a regular source of food and cash for farmers, which is not the case with crops or meat. Moreover, dairy animals are a store of wealth and resilience: farmers can trade the livestock when they need to generate cash or use the livestock as a warranty for loans [33].

Milk production supports women’s empowerment as livestock is a popular asset among rural women in developing countries because animals are easier to acquire than land, for example. According to statistics, dairy cows are directly owned by women in 25% of cattle-keeping households, which implies that over 37 million dairy farms are female-headed [34]. Dairy often serves as the first stepping-stone for rural women to start consolidating a better place for themselves in society, especially in rural areas [35].

1.3. Dairy Production in Suceava County

Suceava County occupies a distinct place in the Romanian economy due to its natural diversity and existing resources. The topography of the county is divided as follows: mountain area 53%, plateau area 30%, and meadow area 17% [36,37].

Given that pastures and hayfields represent almost half of Suceava’s agricultural area, the pastoral potential is high, which makes cattle breeding the preferential agricultural activity in the area. In fact, animal breeding is an ancient occupation of the inhabitants in this area [38]. In 2018, Suceava County had the highest share (6.9% from total Romania) of cattle population in the country [39]. The dairy products made in the Dornelor Basin area are well-known and largely appreciated nationally and internationally as well. Animal husbandry in Suceava County is largely managed by small or micro-enterprises, usually individual holdings (96%) [39]. In 2018, there were 86,335 dairy cows in Suceava County, and a total production of 3035 tons of milk was produced that same year [40,41].

The marketing of milk and dairy products in Romania, including for consumers in Suceava County, is achieved through several distribution channels: supermarket/hypermarket chains and food stores, specialty stores, agri-food markets, online stores, and direct delivery to the consumer [42].

1.4. Brief Presentation of Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs)

Overall, SFSCs are perceived as highly innovative and are on a continuous reinventing process within the developed economies. Romania has a long tradition in this respect as, during the communist period, SFSCs were a survival solution for most urban citizens who, for lack of food, had to get food supplies from their countryside relatives, friends, or small farmers.

The earliest research on SFSCs was carried out by Marsden and collaborators [43], who identified three types of SFSCs according to the relationship between the producer and consumer: (1) Face-to-face or via website; (2) spatial proximity, when products are locally retailed; (3) spatially extended, when retail and sales occur far away from the region of production. In all cases, the diffusion of relevant information differentiates products from commodities [43]. SFSCs are generally defined as “a system of production, processing, and marketing focused mainly on ecological and sustainable methods and means of agri-food production, in which economic activity is carried out and supervised in the region/area of production or its vicinity, generating economic, social, environmental and health benefits to the local communities” [44]. In the developed countries of the European Union, SFSCs have been rediscovered in the last 20 years and are seen as innovative solutions [44] not only for the promotion of healthy eating, support of local agriculture but also for the sustainable development of rural communities. In the food sector, citizen-centered innovations offer an opportunity to transform food systems by shifting power concentration and restoring autonomy in the individual’s relationship with food [45]. According to Butu et al. [46], SFSCs have been regarded as effective solutions for the survival of small local farmers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the COVID-19 sanitary crisis, complemented with the economic crisis, the conventional food chains were less affected due to effective measures applied at the European level (e.g., Green Lanes for agri-food and pharmaceutical products) [47]. The current health crisis has not turned into a real food crisis. The European food network has proved to be functional due to existing SFSCs within local communities.

The resilience to various crisis situations and especially the building of trusting relationships between local producers and final consumers are just some of the arguments to consider that the development of SFSCs will contribute to food safety and security. At the same time, the food provided by small local producers and processors through alternative chains is perceived to be healthier and contributes to the development of healthy eating behavior [48,49,50].

Although the literature has expanded considerably in the last decade, as evidenced by the numerous scientific articles on the subject, relatively few studies analyze short supply chains strictly in the dairy sector. A good example in this regard is provided by Sellitto et al. (2017), which analyzes some critical success factors of SFSCs in the milk and dairy sector from Italy and Brazil [49]. The authors identified some critical success factors that characterize SFSCs in the milk and dairy sector, such as:

- environmentally friendly operations;

- specificity of territorial brands;

- direct and ethical relationships between producers and consumers;

- organic production;

- food safety and traceability, especially after the worldwide melamine milk scandal in 2008 [51];

- cultural heritage;

- consumer’s health;

- local work;

- cooperation;

- pride.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective and Hypotheses

The objective of this study was to identify behavioral changes during the COVID-19 crisis among consumers of dairy products in the short food supply chains in Suceava County (Romania). To achieve this goal, three working hypotheses were formulated.

Hypothesis 1.

The COVID-19 crisis causes significant changes in the behavior of dairy consumers in the short supply chain.

Hypothesis 2.

Behavioral changes occur mainly for married consumers, family values having an important role in the individual reaction to the COVID-19 crisis.

Hypothesis 3.

Behavioral changes trigger digital transformation of short chains of dairy products distribution.

2.2. Methodology

The design of this research involves a mixed, quantitative, and qualitative methodology. In the first phase, a cross-sectional research was conducted based on a survey applied in Suceava County, Romania. Then, to refine the results, the quantitative analysis of the data was complemented with a qualitative interpretation of anthropological and ethnographic nature. Anthropological analysis of consumer research addresses the study of the social meaning of consumer behavior [52]. It is focused on understanding the relations between producers and consumers [53]. Marketing anthropologic research tackles the boundaries of traditional survey methods by asking questions and encourages the advancement of methods beyond scaled response metrics [54].

Ethnography is an investigation method focused on interpreting informal interviews with the aid of on-site observations [55].

All in one, anthropological interpretation is based on data of social behavior, while ethnographic interpretation relies on local data of the same behavior. Therefore, anthropologically informed ethnography is a suitable methodology when trying to understand how a product category fits into consumers’ decisions in real-time and describe their experiences contextually, holistically, and symbolically [56].

2.3. Data Collection

The questionnaire underlying this study was applied in Suceava County between 10 April and 15 May 2020. It was applied online, by email, and on the social media platform Facebook (the most used social media app in Romania). The survey was conducted according to the current market research standards and general data protection regulations. The participants were informed about the objective of the research and were assured that the data collected would only be used for scientific purposes. To ensure the anonymity of the participants, no personal identification data were collected.

The questionnaire included four categories of questions. The first category comprised eight questions aiming to identify the socio-demographic profile of the respondents (age, marital status, gender, education, number of people in the household, county, and locality). The second category included three questions intending to identify the respondents who bought dairy products before the COVID crisis (16 March 2020), during the emergency state, and those who declared that they would buy after the end of the crisis. The third category asked the question regarding the favorite type of dairy products preferred by the respondents. The last category comprised five questions related to the preferred way of ordering, the frequency of placing orders, the minimum value of the order, and the payment method. A total of 465 questionnaires were received, out of which 460 interventions were validated as complete. Only 447 responses were used in the analysis, representing respondents who stated that they were interested in purchasing dairy products directly from producers, with home delivery.

The data were compiled, tabulated, and analyzed in accordance with the hypothesis of the study and the argumentative scheme. To better visualize and process the data collected, the following software was used: Excel software (version 365, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 21.0, IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA) [57], and R Programming software (version 1.1.456; free software from the R. foundation, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [58,59,60,61,62,63].

3. Results

3.1. Primary Data Analysis

In order to respond to the hypotheses of this study, the primary data analysis aimed at:

- identifying the main data of the sociodemographic profile of the respondents (Table 2);

- identifying the main data on consumer behavior (Table 3);

Table 3. Specific frequencies of consumer behavior.

Table 3. Specific frequencies of consumer behavior. - identifying the main data regarding the frequency of purchase, according to the categories of dairy products purchased (Table 4);

Table 4. Frequency of responses by dairy product categories.

Table 4. Frequency of responses by dairy product categories. - identifying the main data on the digital purchasing behavior of respondents (Table 5).

Table 5. Frequency of responses on respondents’ preferred channels for receiving offers of dairy products accessible through direct purchase.

Table 5. Frequency of responses on respondents’ preferred channels for receiving offers of dairy products accessible through direct purchase.

In Table 2, it can be seen that 61% of respondents are women, 76% of respondents are married, 65% are from households where between 2 and 4 people live, and at least 73% have High School or Bachelor’s Degree. By comparing the age categories of the respondents with the age categories of the inhabitants from the analyzed area (Table 1), the following percentage data resulted: respondents ranging between 19 and 34 years old represent 0.081% (of the total population from the same age category), those aged between 35 and 49 represent 0.115%, those included in the 50–64 category represent 0.065%, and those over 65 years old are merely 0.016%. The batch of the questionnaire represents 0.058% of the population of Suceava County. The number of valid answers is greater than the sample size (384), the confidence level is 95%, and the error margin is 5% for the total population in the case study area.

Table 3 shows that most of the respondents (90%) prefer to choose the ordered products themselves, 59% prefer to buy the products based on a monthly subscription, most of the respondents buy weekly and once every two weeks (69%), 53% prefer cash payment, 23% bought using this system before the onset of the lockdown as well, 30% bought during the crisis, and 70% say they will buy using this system after the crisis.

Table 4 shows that most respondents prefer to buy dairy products using this system as follows: 77% buy milk, 97% buy cheese, 62% buy yogurt, 73% buy sour cream, and 56% buy butter.

Table 5 describes the channels preferred by consumers to be informed about the supply of dairy products available through direct purchase from producers. Thus, it is observed that most respondents do not feel comfortable with direct presentation systems (only 1% prefer the phone presentation and only 1% prefer direct contact). In this context, the favorite channels are Facebook (58%) and Website (42%).

Table 6 presents the preferred channels to order dairy products directly from producers. According to the recorded frequencies, the preferred channel is phone (50%), followed by online platform order (41%), online form order (38%), and Facebook (33%).

Table 6.

Frequencies of responses on consumer preferred channels for ordering dairy products purchased directly from producers.

3.2. Results on Hypothesis 1. The COVID-19 Crisis Causes Significant Changes in the Behavior of Dairy Consumers in Short Food Supply Chains

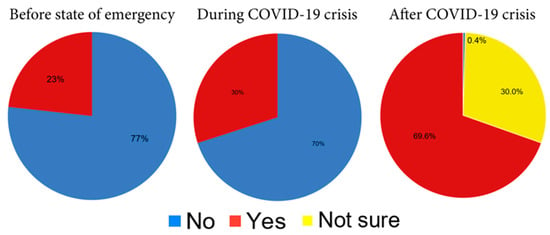

To challenge Hypothesis 1, the first thing to do is to have a look at the series of data on purchasing preference before the onset of the state of emergency, during the crisis, and after the end of the crisis. In Figure 2, the pie chart on the left represents the frequency distribution of those who bought dairy products directly from the producer before the onset of the state of emergency. The pie chart in the middle shows the distribution of those who bought dairy products in this system after the onset of the state of emergency. The pie chart on the right also shows the distribution of respondents’ preferences to buy or not in this system after the end of the crisis.

Figure 2.

Frequency of preferences to purchase dairy products directly from the producer, before the onset of the state of emergency, during the crisis, and after the crisis.

Figure 2 shows a non-significant variation between the purchasing preferences in this system before the onset of the state of emergency and those during the crisis. The increase is only 7 percent. In addition, out of the 134 (30%) respondents who bought using this system after the onset of the state of emergency, only 67 (14%) bought before the onset of the state of emergency. This particular behavior is present for only 14% of respondents. The other respondents turn out to be only occasional buyers. This result contradicts Hypothesis 1—“The COVID-19 crisis causes significant changes in the behavior of dairy consumers in short food supply chains”. In contrast, it is to be noted that the percentage of those who say they will buy dairy in this system after overcoming the crisis is 70%, which is a significant variation (Figure 2).

To better understand these seemingly contradictory data, anthropological and ethnographic interpretations are suitable. Accordingly, from an anthropological point of view, when dealing with projections in the future as the expectations are influenced (either positively or negatively) by the information received and the contextual situation [64]. Thus, it is to remember that since the onset of this pandemic general public has been largely exposed to the idea that in order to survive the contemporary society must change in the sense of a greater concern for nature and health. Therefore, we are also dealing with a behavioral reaction in the sense of the desire to change the lifestyle both individually and collectively.

An in-depth-insight into the sociology of the dairy market in the Suceava area resulted from the ethnographical analysis. It should be noted that, in Romania (and by extension, in Suceava County), there is not a very large diversity of dairy categories, and the processed dairy products with longer shelf life are little represented. The primary or semi-prepared products with a short shelf life (milk, yogurt, cream, fresh cheese) are the main diary source present on the market shelves. The offer for these products is diverse in the retail system and the consumer’s desire to ensure food safety (as a family value) determines the buying decision.

It may be concluded that non-significant behavioral changes occur. Significant differences appear in terms of values through the future projections made by consumers when this crisis eventually comes to an end. Thus, there is a real potential for change in this market, and it can be exploited by implementing strategies and policies of branding, by working towards increasing awareness on healthy food education and increasing confidence in short food supply chains. This potential is also shown in a previous paper [65] built on a questionnaire of a similar structure, but focused on the behavior of buyers of fresh vegetables directly from the producers.

3.3. Results on Hypothesis 2. Behavioral Changes Occur Mainly for Married Consumers, with Family Values Playing an Important Role in the Individual Reaction to the COVID-19 Crisis

In contemporary society, the family is perceived as the basic cell of society [66], and family relations are strong. However, in Romania (including Suceava County), the extended family model differs from other cultures such as Italy, Spain, Brazil, Chile, and Colombia [15]. While the usual family comprising spouses and children often lives with grandparents in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia, this is less common in Romania. Despite the previous statement, social behavior focuses on the values of the family.

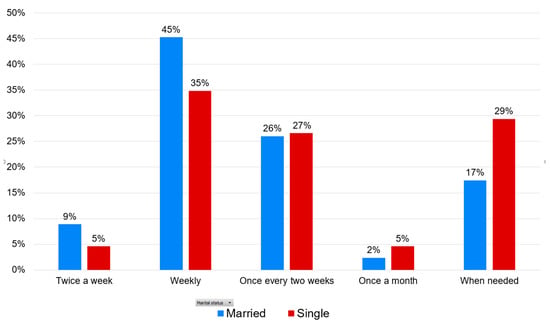

This becomes clearer in Figure 3. Married consumers prefer to buy dairy products directly from the producer more frequently than unmarried consumers (weekly and twice a week). This is a specific behavior, meaning that it works based on a pattern. In addition, as long as healthy eating behavior is one of the fundamental values in the private space of a family [42], the purchase of dairy products directly from the producer is perceived as a solution for compliance with these values.

Figure 3.

Periodicity of purchasing dairy products directly from the producer, depending on marital status.

An anthropological interpretation could go even further. In the cluster of married respondents, it may be stated that there is a higher confidence in dairy products delivered directly from producers. This is mainly because dairy products are perceived as healthy food and, consequently, they should be included in the children’s diet. At the same time, recent studies suggest that frequent family meals are not enough to improve diet quality [67,68]; thus, it is important to look beyond the frequency of family meals by focusing on the context and nature of the meal [67,69]. In this sense, at the level of the family cell, including the purchase of quality products in the supply chain can contribute to diet quality and thus the maintenance of the health of the family.

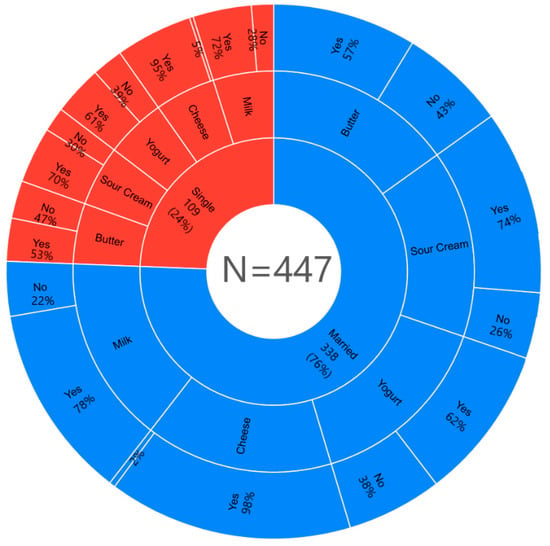

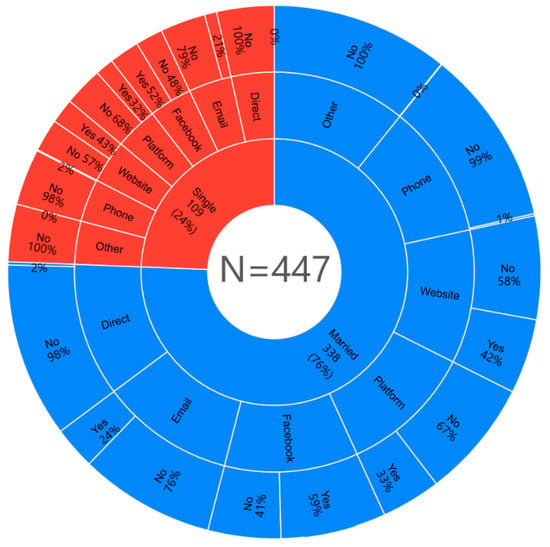

Figure 4 shows that within the purchasing system directly from the producer, respondents in the single category (N = 109) buy cheese (95%), milk (72%), sour cream (70%), and yogurt (61%). Married respondents (N = 338) state that they prefer the following product categories: cheese (98%), milk (78%), sour cream (74%), and yogurt (62%). Preferences have similar values in both clusters of respondents (single and married). This fact, from an ethnographic point of view, proves that there is a symbolic system of acquisition common to all respondents. In other words, all respondents claim a common gastronomic culture, sharing common values, which determine a similar purchasing behavior through their attitudes.

Figure 4.

Preferences for dairy categories by marital status.

This common purchasing behavior can be better understood through ethnographic data related to food nutrition. From an anthropological point of view, dairy products are considered healthy foods globally, being recommended especially for dietary calcium intake [70]. Ethnographically, however, there are some specific differences. Milk is a basic element in daily purchases and has an important dietary role, especially in children [71]. Milk is often consumed at breakfast. Cheese is consumed throughout the day, at breakfast, lunch, and dinner [1]. Cheese and cheese products are used as an ingredient for many dish recipes (pie, polenta, pizza topping, snack) and also have a longer shelf life and can be preserved over the winter, out of season. Unlike other gastronomic cultures, Romanians consume a lot of sour cream, both fresh and added to other dishes. It is consumed mainly at lunch and dinner. Yogurt is a product consumed especially at lunch and dinner, being a product recommended for people with lactose intolerance [72]. Accordingly, of all these products, milk and yogurt have the strongest social character within the family, as long as breakfast and dinner are the meals when family members meet most often.

Figure 4 also shows that butter is the least purchased product directly from manufacturers for both singles (53%) and married (57%) individuals. An explanation could be that butter sold in this purchasing system has a high-fat percentage (at least 80%).

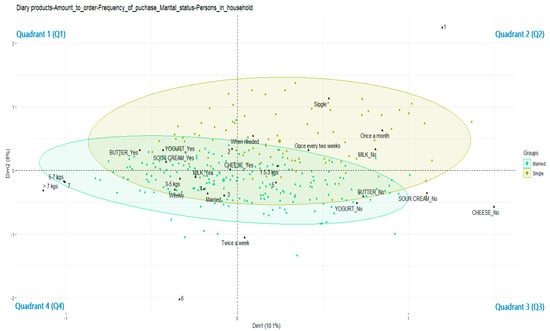

To understand other ways in which family values can influence purchasing behavior, the data were represented by using a biplot with multivariate correspondence. This data representation tool is useful for the identification of strong or weak correlations between more than three categories of data. The data bipolarity distribution is given by two categories selected as the main subject of analysis. For our data, the single and married categories were chosen, and their representation is given by the two ellipses (Figure 5). The intersection of the ellipses is the area with the strongest similarities in purchasing behavior, depending on the other categories chosen. The two axes have an operational role, and they determine both the center of maximum similarity in connection with the interpretations made and four quadrants (Q1–Q4, numbered from the top left, clockwise) to simplify the interpretations. Another important aspect is the proximity to the intersection of the axes. The closer it is to this point, the more values a category has in the dataset. It can be seen, thus, that the married category has much more values than the single category. However, the most important aspect is the size of the angle that two categories make with the center of the intersection of the axes. The smaller the angle, the stronger the correlation between the two categories of data.

Figure 5.

Biplot with multivariate correspondence depending on dairy products, marital status, amount to order, persons in the household, and frequency of purchase of dairy products directly from producers.

Figure 5 shows that the analyses described so far are confirmed, and at the same time, allows more conclusions to be drawn. It can be observed that those included in the single category, as well as those in families of two, buy dairy products directly from the producer, especially when the need arises. Families of 3, 4, or 5 people buy dairy products directly from the producer, especially weekly or twice a week. Accordingly, it may be concluded that the presence of children in the family leads to a higher frequency of purchasing dairy products directly from producers. This conclusion is also reinforced by the observation that, in Figure 6, there are stronger correlations between families with 3 or 4 members and the purchase of milk rather than cheese or other dairy products. It should be highlighted that, from an anthropological point of view, milk is considered an indispensable food, especially in children’s nutrition. In the case of two-member families, yogurt, butter, sour cream, and cheese are preferred over milk. Therefore, it can be stated that purchasing behavior is influenced by family values in the symbolic systems of healthy living and food safety.

Figure 6.

Preferred channels of information on dairy products purchased directly from producers, depending on marital status.

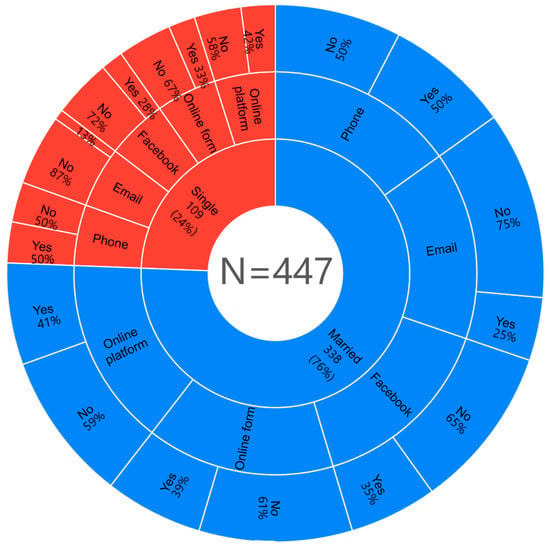

3.4. Results on Hypothesis 3. Behavioral Changes Trigger Digital Transformation of Short Chains of Dairy Products Distribution

To verify Hypothesis 3, we identified those data that appear to be significant or atypical regarding the behavior of respondents in the information and ordering system regarding these products. These aspects must be analyzed by comparing the cluster of the married with that of the unmarried individuals. In this respect, in terms of the symbolic information system, consumer behavior is similar in both the married and unmarried groups (Figure 6). An important argument to be considered is whether this is due to common values that are consolidated into common purchasing behaviors.

Things change, not significantly but noticeably, when comparing the information channels on dairy products and preferred channels for ordering. Email is preferred by 25% of the married respondents and 13% of the singles. Facebook appears in the preferences of 35% of married consumers and for unmarried, 13%. Differences also occur in the case of online platforms: they are favored by 59% of married people and 42% of singles. Online forms are chosen by 39% of married people and 28% of singles. In the case of the phone, the percentages are almost equal, around 50% (Figure 7). To better understand these data on control channels, qualitative behavioral interpretations were used.

Figure 7.

Preferred channels for ordering dairy products directly from the producer, depending on marital status.

Thus, as presented in Figure 7 in both clusters (married and single) the highest values are for ordering by online platform and phone. These are also the only channels through which the consumers find additional information about the characteristics of the products and which can provide real-time information on order and distribution.

In this context, we believe that the respondents have expressed their desire to be more informed in the buying process, in terms of product quality and distribution process. Ordering via email, a simple online form, or a Facebook message cannot be made in a context where the consumer can find out more about the ordered product or the purchase procedure.

Besides the separate analysis of the preferred channels for information and those preferred for ordering, interesting data can be revealed by comparing the two. Thus, it can be noted first that, both in terms of information about dairy products and in terms of ordering them, consumers prefer the same channels: Facebook, Websites, and Online platforms. The only notable difference lies in the preference for placing the orders over the phone, except for being disturbed by a product promotion. Accordingly, the consumer wants to have a personal experience both in terms of identifying and selecting products and ordering them as well.

4. Discussions

For a better verification of the hypotheses, anthropological and ethnographic interpretations were used. They are based on the survey data and further complimented with the literature in the field. Anthropological interpretation is based on universal data of social behavior, while ethnographic interpretation relies on local data of the same behavior. These interpretations start from the idea of the value, attitude, behavior model (VAB), although we did not resort to a systematic approach to this model. From this model, only the basic idea was used, meaning that the assumed values influence the behavior through attitudes [73]. This approach supports the present research, mainly because we can make precise distinctions between family values, consolidated attitudes or new attitudes (in times of crisis), and consumer behavior determined by these values and attitudes. The socio-cultural values of the inhabitants of Suceava County have an influence on consumer behavior because they have a locally focused community with a strong emphasis on preserving traditions and identity resilience [74].

4.1. Discussions on Hypothesis 1. The COVID-19 Crisis Causes Significant Changes in the Behavior of Dairy Consumers in Short Food Supply Chains

There are no significant changes between the behavior before the COVID-19 crisis and that during the pandemic. But, at the level of future projections, there are intentions to change the buying behavior in a positive sense. These intentions will exert pressure on SFSCs and, in this regard, this market needs to mature and meet consumer preferences and values. Therefore, producers should be aware that purchasing milk and dairy products directly from producers is a way of controlling the quality and authenticity of products based on their own experience. This message should be supported by transparent business and high-value products that inspire as much trust as possible.

In this sense, a sustainable and attractive market brings as many buyers as possible and, through direct purchase from producers, the difference between the price of milk in stores and the price paid by buyers to producers ends up being divided between consumer and producer. Through direct procurement, both parties involved in such standard transactions benefit economically and financially, so that both suppliers and final buyers are no longer forced to pay the significant amount of commissions and fees charged for the sale of goods at various points of sale in retail as these cost categories are usually reflected in the final selling prices.

4.2. Discussions on Hypothesis 2. Behavioral Changes Occur Mainly for Married Consumers, Family Values Having an Important Role in the Individual Reaction to the COVID-19 Crisis

As it was noted in the previous section on Hypothesis 2, one could be tempted to say that there is not a direct determination between family values and purchasing behavior. The similarities between the data (at the level of both clusters: single and married) could lead to the conclusion that, once a family is founded, no new values are established that could influence the purchasing behavior. However, this should be viewed in exactly the opposite way: single people, coming out of the small family, keep the consolidated values of the family they were part of in the past. Moreover, previous research highlighted the fact that food preferences and eating behaviors develop early in life [75]. Healthy eating in the first five years is linked to current and future health [76,77,78], and both dietary varieties seeking and untreated overweight/obesity [79] are likely to track from childhood into adulthood [80]. It is, therefore, about a community of consumers with a specific behavior within the family, starting from values that, through purchasing attitudes, influence the general behavior of the consumer. At the same time, it can be noticed that the presence of children in the family leads to a greater concern of consumers for food safety.

Accordingly, trust can be considered the most important vector for strengthening a relationship between producers and consumers and increasing local food production and consumption can increase consumer confidence in food [81]. To increase trust, manufacturers need to offer quality products and constantly communicate with consumers. Thus, producers could promote their products in family-oriented social media groups (for example, Facebook groups of mothers, health lovers, or consumers who support local producers). Establishing a direct relationship with producers is also a first step in developing a partnership in terms of programming quantities, product range, and periodicity of orders. In the case of families with children, collaboration with a local producer can be diversified, including educational visits to the provider’s household. At the same time, given that milk production is also carried out with a certain seasonality [82,83], as there are fluctuating periods in terms of the quantity obtained, producers should develop lasting relationships with consumers, as they cannot constantly ensure the same quantity and the same range of products on the market.

4.3. Discussions on Hypothesis 3. Behavioral Changes Trigger Digital Transformation of Short Chains of Dairy Products Distribution

It can be noticed that we are dealing with a community of consumers interested in a distribution system best adapted to the digital transformation of contemporary society. When searching for information and placing orders, the consumers want to have access to additional information about the purchased products [84]. Thus, the need for additional information demanded by the consumer when purchasing dairy products directly from the producer exerts pressure on the digital transformation of SFSCs. Digitization and new technologies in the agri-food sector bring both opportunities, challenges, and also risks [85].

This digital transformation must take place in the sense of developing media channels for the presentation of the product offering and for order management. Thus, there are additional benefits with effects on the management of the activity, in terms of implementing the necessary measures for card payments and bank transfer, as long as 47% of respondents prefer this system. However, at the same time, the implementation of measures necessary for the digital transformation of small producers and the adaptation of their businesses, meaning accepting payments by bank card and/or bank transfer, can have effects in the sense of increasing the prices of dairy products. On the other hand, the digital transformation involves an exit of producers from the grey area of the economy, with beneficial effects for both producers, consumers, and the economy in general.

One last aspect worth mentioning is the innovative nature of the digital transformation. Thus, producers need to find smart solutions and harmonize modern tools with the local and traditional character of the products they put into circulation. The digital transformation must take place without affecting the local culture, which, through traditional narratives, adds value to dairy products.

4.4. Research Limitations

The limitations of our study are generated by four important factors: the area investigated (as it regards only one county in Romania), the time of application of the questionnaire (between 10 April and 15 May 2020), and the category of products addressed (dairy). Starting from these limiting factors, it can be stated that the results of the study clearly highlight only the behavioral changes of the group of respondents from a well-defined administratively territorial geographical area, in a period marked by affective-emotional pressure, uncertainty and limitations of movement and action, related to the purchase of dairy products directly delivered from producers. The results obtained represent a starting point for the construction of further and extensive research at the national level. Another limitation is that the number of dairy cows is constantly declining, especially in rural areas adjacent to large urban centers; fresh (raw) milk and dairy products obtained by small producers are in small quantities, and thus, their availability on the market is limited. Finally, a limitation of this research is given by the necessity of seizing the “behavioral change” in a cross-sectional design.

The present study could be supplemented by additional research, using theme networking methods on the emotional reactions of social media groups on dairy products delivered directly by the producer. For a comparative analysis aimed at identifying the behavioral changes that have been consolidated with regard to the acquisition of dairy products according to the short food supply chain criteria, we are planning to continue research in the same area of interest 12 months after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic alert in Romania.

5. Conclusions

The market of dairy products delivered directly from producers in Suceava County, is a market that has not fully matured or made the most of its growth potential. At the same time, from our observations, there is a community of consumers which is increasingly oriented towards healthy products, obtained in lasting and sustainable production systems and distributed intelligently and innovatively through short food supply chains.

Issues such as overcoming the current global health crisis, implementation of measures to combat its effects, and the experience gained during this challenging period, are strongly mirrored by the struggle of small local producers/processors who should be strongly supported by clearer development strategies and policies. We firmly support this, especially given that they have gradually lost their rightful place in the agri-food sector in recent decades [86]. In the post-crisis recovery period, small producers and local processors will play an important part, and, even more, there will be a genuine need for the development and promotion of SFSCs. It is our opinion that the development philosophy of agroeconomics must change and make room to a place where conventional agriculture and alternative agriculture coexist, the desideratum being feasible in maintaining a balance of interests of the two parties involved in these subsectors [46]. At the same time, micro processing and short-chain capitalization of milk and dairy products can counterbalance the dependence of small producers on large processors, contributing to their resilience [87] in a complex market where consumers are increasingly aware of values such as health, quality of life, food safety, and security and digital transformation.

This scientific paper could have a global impact, especially in the regions where animal husbandry is managed by small-scale producers, such as individual holdings. Making the best use of dairy products via short food supply chains represents an alternative solution to supplying the urban population with products obtained by local producers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D.V., I.S.B. and S.R.; data curation, I.S.B., L.T., S.D. and O.C.; formal analysis, I.S.B., L.T., S.D. and A.B.; funding acquisition, G.S.; investigation, C.D.V., I.S.B., G.S., M.B. and L.T.; methodology, C.D.V., I.S.B., M.B. and A.B.; project administration, I.S.B.; resources, S.R., G.S., L.T. and O.C.; software, C.D.V. and M.B.; supervision, M.B.; validation, S.R., M.B. and G.S.; visualization, S.R. and M.B.; writing—original draft, C.D.V., I.S.B. and S.R.; writing—review and editing, S.R., C.D.V., M.B. and A.B. All authors made equal contributions to this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was co-funded by CENTRUL PENTRU ECONOMIE SI DEZVOLTAREA AGRICULTURII LTD, a private company research from Iasi, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to Sonia Bulei for their contributions to the English review of the manuscript. We would like to thank our reviewers for the suggestions which led to improving this material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Voinea, L.; Popescu, D.V.; Bucur, M.; Negrea, T.M.; Dina, R.; Enache, C. Reshaping the traditional pattern of food consumption in romania through the integration of sustainable diet principles. A qualitative study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgescu, B. România și Europa. Acumularea Decalajelor Economice (1500–2010); Editura Polirom: Iași, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchins, K. Rumania, 1866–1947; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 156–157, 268. [Google Scholar]

- Şandru, D. Populaţia Rurală a României Între Cele Două Războaie Mondiale; Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România: Bucharest, Romania, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Axenciuc, V. Evoluţia Economică a României: Cercetări Statistico-Istorice 1859–1947; Editura Academiei Române: Bucharest, Romania, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoruță, S. Epidemiile de Ciumă în Moldova la Începutul Secolului al XIX-lea—Studiu și Documente; Editura Universității Alexandru Ioan Cuza: Iași, România, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, P.; Poudel, M.R.; Gautam, A.; Phuyal, S.; Tiwari, C.; Bashyal, N.; Bashyal, S. COVID-19 and its Global Impact on Food and Agriculture. J. Biol. Todays World 2020, 9, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. From biomedical to politicoeconomic crisis: The food system in times of Covid-19. J. Peasant Stud. 2020, 47, 944–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C. Resilience of local food systems and links to food security—A review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, S.; Béné, C.; Hoddinott, J. Conceptualising COVID-19’s impacts on household. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 769–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhwani, V.; Deshkar, S.; Shaw, R. COVID-19 lockdown, food systems and urban–rural partnership: Case of Nagpur, India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulighe, G.; Lupia, F. Food first: COVID-19 outbreak and cities lockdown a booster for a wider vision on urban agriculture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, M.; Brander, M.; Kassie, M.; Ehlert, U.; Bernauer, T. Improved storage mitigates vulnerability to food-supply shocks in smallholder agriculture during the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. The food systems in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic crisis. Foods 2020, 9, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Roso, M.B.; de Carvalho Padilha, P.; Mantilla-Escalante, D.C.; Ulloa, N.; Brun, P.; Acevedo-Correa, D.; Arantes Ferreira Peres, W.; Martorell, M.; Aires, M.T.; de Oliveira Cardoso, L.; et al. Covid-19 confinement and changes of adolescent’s dietary trends in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia and Brazil. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food Outlook—Biannual Report on Global Food Markets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Institutul Național de Statistica. AGR101A—Land Fund Area by Usage, Ownership form, Macroregions, Development Region and Counties. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Geo-spatial.org—Coronavirus Covid 19 România. Available online: https://covid19.geo-spatial.org (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Ministerul Afacerilor Interne Ordonanța Militară nr. 6 din 30 Martie 2020, Privind Instituirea Măsurii de Carantinare Asupra Municipiului Suceava, a Unor Comune Din Zona Limitrofă, Precum și a Unei Zone de Protecție Asupra Unor Unități Administrativ-Teritoriale Din Județul Suceava. Available online: https://sb.prefectura.mai.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/sites/28/2020/04/ORDONANTĂ-MILITARĂ-nr.-6-din30-martie-2020.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Stanciu, M.; Mihăilescu, A.; Humă, C. Raport Social al ICCV 2020. Stare de Urgență pentru Consumul Populației—Recurs la Reflecție Asupra Trebuințelor Esențiale; Institutul de Cercetări pentru Calitatea Vieții—Academia Română: Bucharest, Romania, 2020; Available online: https://www.romaniasociala.ro/raport-social-al-iccv-stare-de-urgenta-pentru-consumul-populatiei/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- LEGE nr. 55 din 15 Mai 2020 Privind Unele Măsuri Pentru Prevenirea și Combaterea Efectelor Pandemiei de COVID-19. Available online: http://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/225620 (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Institutul Național de Statistica. POP107D—Population by Residence on 1 January 2020, According to Groups of Age, Gender, County and Localities (Populația după Domiciliu la 1 Ianuarie pe Grupe de Vârstă, Sexe, Județe și Localități). 2020. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- EC.EUROPA. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/10474907/1-05032020-AP-EN.pdf/81807e19-e4c8-2e53-c98a-933f5bf30f58 (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Curs de Guvernare—Cele mai Recente Date Definitive Privind PIB-ul pe Regiuni în România. Implicații Pentru Adoptarea Euro. Available online: https://cursdeguvernare.ro/cele-mai-recente-date-definitive-privind-pib-ul-pe-regiuni-in-romania-implicatii-pentru-adoptarea-euro.html (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Data Worldbank. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=RO (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Filipescu, C. Marea Enciclopedie Agricolă; Editura P.A.S.: Bucharest, Romania, 1940; Volume III, p. 481. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, X. Chinese consumers’ preferences for attributes of fresh milk: A best–Worst approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.C. Milk nutritional composition and its role in human health. Nutrition 2014, 30, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghin, I. Revista Laptelui. Organ de Îndrumare și Informații, Anul III, Nr. 2; Comitetul Național Român al Laptelui: Bucharest, Romania, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- OECD-FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2016–2025; OECD/FAO: Paris, France, 2016.

- Bórawski, P.; Pawlewicz, A.; Parzonko, A.; Harper, J.K.; Holden, L. Factors shaping cow’s milk production in the EU. Sustainability 2020, 12, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, V.E.; Solis, D.; Del Corral, J. Determinants of technical efficiency among dairy farms in Wisconsin. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The Global Dairy Sector: Facts. Available online: https://www.fil-idf.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/FAO-Global-Facts-1.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Njuki, J.; Sanginga, P.C. (Eds.) Women, Livestock Ownership and Markets. Bridging the Gender Gap in Eastern and Southern Africa; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Empowering Women in Afghanistan: Reducing Gender Gaps through Integrated Dairy Schemes; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Suceava, C.J. Consiliul Judetean Suceava. Available online: http://www.cjsuceava.ro/index.php/ro/descrierea-generala-a-judetului-suceava (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Florian, V.; Rusu, M.; Roșu, E.; Chițea, M.; Brumă, I.S.; Pocol, C.B. Behavioural Factors and Ecological Farming. Case Studies, Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2020, 20, 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Doboș, S.; Matei, D. Turismul rural în Moldova între istorie și actualitate. In Turismul Rural Românesc în Contextul Dezvoltării Durabile: Vol. XX; Talabă, I., Gițan, D., Haller, A.-P., Ungureanu, D., Eds.; Tehnopress: Iasi, Romania, 2010; pp. 77–78, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Institutul Național de Statistică. AGR201A—Livestock, by Animal Category, Ownership form, Macroregions, Development Regions and Counties, at the End of Year. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Institutul Național de Statistică. Available online: https://suceava.insse.ro/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/141-Efectivele-de-animale-la-1-decembrie.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Institutul Național de Statistică. Available online: https://suceava.insse.ro/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/144-Produc%c5%a3ia-agricol%c4%83-animal%c4%83-%c3%aen-anul.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Butu, A.; Vasiliu, C.D.; Rodino, S.; Brumă, I.-S.; Tanasă, L.; Butu, M. The process of ethnocentralizing the concept of ecological agroalimentary products for the romanian urban consumer. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Banks, J.; Bristow, G. Food Supply Chain Approaches: Exploring Their Role in Rural Development. In Sociologia Ruralis; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 2000; Volume 40, pp. 424–438. [Google Scholar]

- Kneafsey, M.; Venn, L.; Schmutz, U.; Balázs, B.; Trenchard, L.; Eyden-Wood, T.; Sutton, G.; Bos, E.; Blackett, M. Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in the EU. A State of Play of their Socio-Economic Characteristics; Joint Research Center—Institute for Prospective Technological Studies: Luxembourg, 2013; Available online: http://ipts.jrc.ec.europa.eu/publications/pub.cfm?id=6279 (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Democratizing food systems. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 383. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0126-6 (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Butu, A.; Brumă, I.S.; Tanasă, L.; Rodino, S.; Dinu Vasiliu, C.; Doboș, S.; Butu, M. The impact of COVID-19 crisis upon the consumer buying behavior of fresh vegetables directly from local producers. Case study: The quarantined area of Suceava county, Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission on the Implementation of the Green Lanes under the Guidelines for Border Management Measures to Protect Health and Ensure the Availability of Goods and Essential Services. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transport/sites/transport/files/legislation/2020-03-23-communication-green-lanes_en.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Barska, A.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J. E-consumers and local food products: A perspective for developing online shopping for local goods in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellitto, M.A.; Vial, L.A.M.; Viegas, C.V. Critical success factors in Short Food Supply Chains: Case studies with milk and dairy producers from Italy and Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanasă, L. Benefits of short food supply chains for the development of rural tourism in Romania as emergent country during crisis. Agric. Econ. Rural Dev. Inst. Agric. Econ. 2014, 11, 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Wu, Y. A comparative study of the role of Australia and New Zealand in sustainable dairy competition in the chinese market after the dairy safety scandals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadajewski, M.; Wagner-Tsukamoto, S. Anthropology and consumer research: Qualitative insights into green consumer behavior. Qual. Mark. Res. 2006, 9, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.; Denny, R. Anthropology in consumer research. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Anthropol. 2019. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/anthropology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190854584.001.0001/acrefore-9780190854584-e-9 (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Martin, D.; Woodside, A. Learning consumer behavior using marketing anthropology methods. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 74, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badot, O.; Carrier, C.; Cova, B.; Desjeux, D.; Filser, M. The contribution of ethnology to research in consumer and shopper behavior: Toward ethnomarketing. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2009, 24, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, R. Inspiring brand positionings with mixed qualitative methods: A case of pet food. J. Bus. Anthropol. 2020, 9, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. SPSS Statistics. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- R Core Development Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://softlibre.unizar.es/manuales/aplicaciones/r/fullrefman.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R 2015. Available online: https://rstudio.com/products/team/ (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Package “Factoextra” for R: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. Available online: https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/factoextra/index.html (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, R.A.M.; Chen, Z.J. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (2nd ed.). Meas. Interdiscip. Res. Perspect. 2019, 17, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Optimism, pessimism and self-regulation. In Optimism and Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice; Chang, E.C., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Butu, A.; Vasiliu, C.D.; Rodino, S.; Brumă, I.-S.; Tanasă, L.; Butu, M. The Anthropological Analysis of the Key Determinants on the Purchase Decision Taken by the Romanian Consumers Regarding the Ecological Agroalimentary Products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihăilescu, V. Antropologie. Cinci introduceri; Polirom Publishing House: Iași, Romania, 2007; ISBN (10) 973-46-0533-X. [Google Scholar]

- Loth, K.A.; Horning, M.; Friend, S.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Fulkerson, J. An exploration of how family dinners are served and how service style is associated with dietary and weight outcomes in children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Lobos, G.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Denegri, M.; Ares, G.; Hueche, C. Diet quality, satisfaction with life, family life and food-related life across families: A cross-sectional study with mother-father-adolescent triads. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Grunert, K.G.; Lobos, G.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Denegri, M.; Ares, G.; Hueche, C. A latent class analysis of family eating habits in families with adolescents. Appetite 2018, 129, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-López, N.; Llopis-González, A.; Picó, Y.; Morales-Suárez-Varela, M. Dietary Calcium Intake and Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Spanish Children: The ANIVA Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miclean, M.; Cadar, O.; Levei, E.A.; Roman, R.; Ozunu, A.; Levei, L. Metal (Pb, Cu, Cd, and Zn) Transfer along Food Chain and Health Risk Assessment through Raw Milk Consumption from Free-Range Cows. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown-Riggs, C. Nutrition and Health Disparities: The Role of Dairy in Improving Minority Health Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, P.M.; Lynn, R.K. A Structural Equation Test of the Value-Attitude-Behavior Herarchy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacel, O. Regional Identification in Present Day Romania. The Case Study of Suceava County. Messages Sages Ages 2015, 2, 7–16. Available online: http://archive.sciendo.com/MSAS/msas.2015.2.issue-1/msas-2015-0001/msas-2015-0001.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Birch, L.L. Parental influence on eating behavior: Conception to adolescence. J. Law Med. Ethics 2007, 35, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, F.; Piwoz, E.; Schultink, W.; Sullivan, L.M. Nutrition and health in women, children, and adolescent girls. Br. Med. J. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, J. Health Psychology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, M.; Krolner, R.; Klepp, K.I.; Lytle, L.; Brug, J.; Bere, E. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Part I: Quantitative studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivier, P.; Tomkins, C. Health Consequences of Obesity in Children and Adolescents, Childhood and Adolescent Obesity; Jelalian, E., Steele, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Snuggs, S.; Houston-Price, C.; Harvey, K. Healthy eating interventions delivered in the family home: A systematic review. Appetite 2019, 140, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.B.; Coveney, J.; Henderson, J.; Ward, P.R.; Taylor, A.W. Reconnecting Australian consumers and producers: Identifying problems of distrust. Food Policy 2012, 37, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.C.; Clay, J.S.; De Vries, A. Distribution of seasonality of calving patterns and milk production in dairy herds across the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodall, E.A. An analysis of seasonality of milk production. Anim. Sci. 1983, 36, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R.; Mariani, A. Do Consumers Want More Nutritional and Health Information on Wine Labels? Insights from the EU and USA. Nutrients 2016, 8, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosior, K. Digital Transformation in the Agri-Food Sector—Opportunities and Challenges. Roczniki Naukowe 2018, XX. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tundys, B.; Wiśniewski, T. Benefit Optimization of Short Food Supply Chains for Organic Products: A Simulation-Based Approach. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I. Agroecology and the reconstruction of a post-COVID-19 agriculture. J. Peasant Stud. 2020, 47, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).