Perceived Green Human Resource Management Practices and Corporate Sustainability: Multigroup Analysis and Major Industries Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

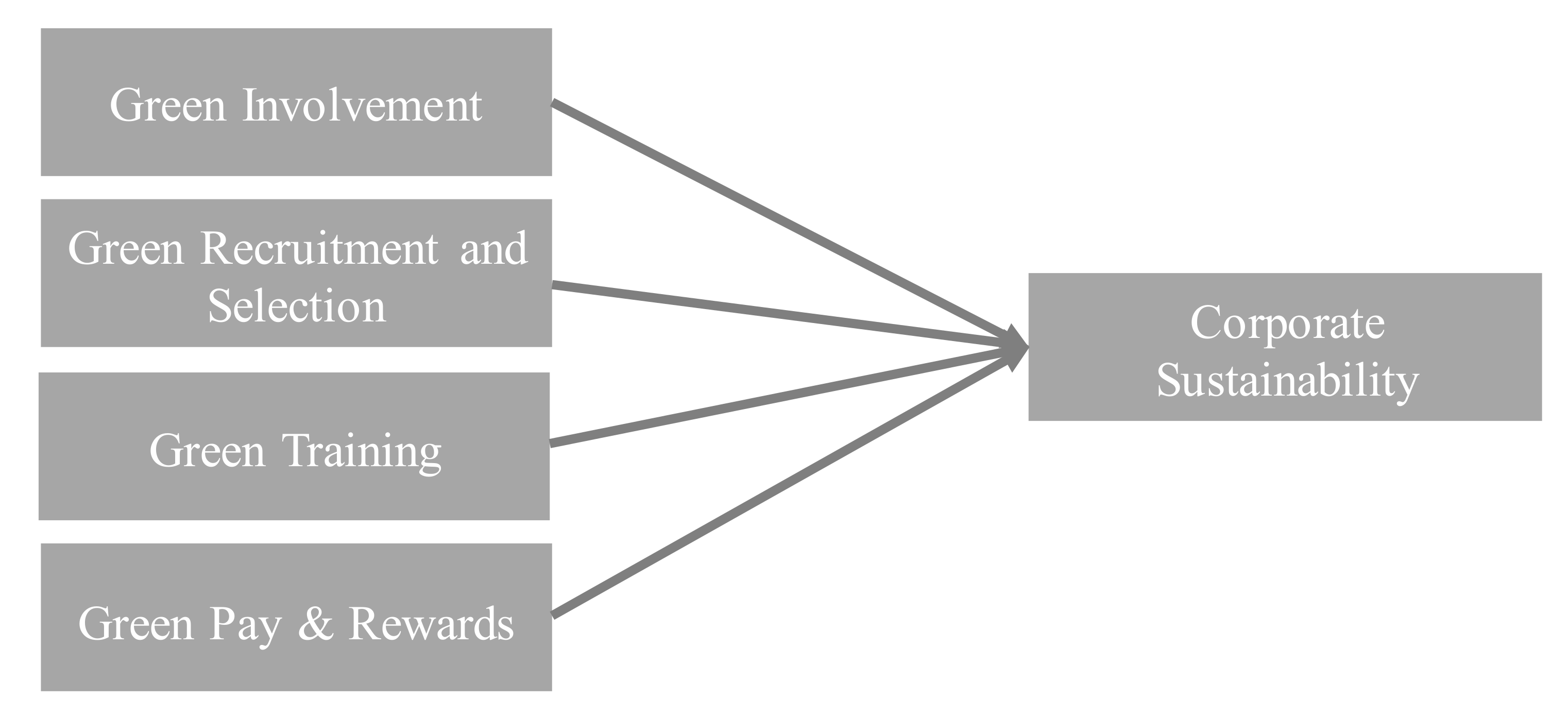

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.2. Corporate Sustainability

2.3. GHRM and Corporate Sustainability

2.3.1. Green Involvement (GI)

2.3.2. Green Pay and Reward (GPR)

2.3.3. Green Recruitment and Selection (GRS)

2.3.4. Green Training (GT)

3. Research Design

3.1. Instrument

3.2. Sample Size and Data Collection

3.3. Demographic Profile of Respondents

4. Data Analysis and Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- We know enough about corporate sustainability.

- Organizations, where operations are based on sustainable growth, social responsibility, and environmental protection, are sustainable organizations.

- Sustainable organizations would consider sustainability as one of the essential components of the corporate culture.

- Sustainable organizations exploit environmental challenges and legislation to their advantage by developing new greener products.

- Ecological regulations add more restrictions on firms.

- Due to ecological constraints, it is okay to think of relocating production to other countries, where ecological requirements are lower.

- Sustainability has to be taken as an important route for the long-term development of the enterprise.

- We attract green job candidates who use green criteria to select organizations.

- We use green employer branding to attract green employees.

- Our firm recruits employees who have green awareness.

- Green organizations have a responsibility to provide a clear developmental vision for the guidance of the employees’ actions in environmental management.

- The green firm shall have a mutual learning climate among employees for green behavior and awareness.

- In green organizations, there should be several formal or informal communication channels to spread green culture within the organization.

- Green organizations are those that involve employees in quality improvement and problem-solving on green issues.

- Green organizations involve their employees by offering practices to participate in environment management (such as newsletters, suggestion schemes, problem-solving groups, low-carbon champions, and green action teams, etc.).

- Those organizations that emphasize a culture of environmental protection are green.

- The green organization will make available green benefits to its employees such as combine transportation and travel to support green efforts.

- Provision of financial or tax incentives to employees is an essential part of the ‘Pay and Reward’ system in a green organization (e.g., bicycle loans, use of less polluting cars)

- Recognition-based rewards in environment management for staff (e.g., public recognition, awards, paid vacations, time off, gift certificates) are given due importance in the green organization.

- Organizations with GHRM must develop training programs in environmental management to increase environmental awareness, skills, and expertise of employees.

- Organizations with GHRM should consider integrating training to create the emotional involvement of employees in environment management.

- Organizations with GHRM will have a defined green knowledge management system (link environmental education and knowledge to behaviors to develop preventative solutions).

References

- Goffee, R.; Jones, G. Creating the Best Workplace on Earth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, M. Green human resource management: Development of a valid measurement scale. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Ramayah, T.; Fawehinmi, O. Nexus between green intellectual capital and green human resource management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Paillé, P.; Jia, J. Green human resource management practices: Scale development and validity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2017, 56, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, H.A.; Jaaron, A.A. Assessing green human resources management practices in Palestinian manufacturing context: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2017, 35, 769–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R.L. Business Cases and Corporate Engagement with Sustainability: Differentiating Ethical Motivations. J. Bus. Ethic 2018, 147, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Ramayah, T.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Sehnem, S.; Mani, V. Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, A.; Inore, I.; Sauna, R. A Study on Implications of Implementing Green HRM in the Corporate Bodies with Special Reference to Developing Nations. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Saeed, B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.-M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneva, J.M.; Pajares, J.H. Corporate social responsibility performance and sustainability reporting in SMEs: An analysis of owner-managers’ perceptions. Int. J. Sustain. Econ. 2018, 10, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järlström, M.; Saru, E.; Vanhala, S. Sustainable Human Resource Management with Salience of Stakeholders: A Top Management Perspective. J. Bus. Ethic 2018, 152, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D. Translating stakeholder pressures into environmental performance—The mediating role of green HRM practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 27, 262–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Rahman, H.U.; Khan, M.; Ali, W.; Shad, F. Addressing endogeneity by proposing novel instrumental variables in the nexus of sustainability reporting and firm financial performance: A step-by-step procedure for non-experts. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 3086–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Rahman, H.U.; Ali, W.; Habib, M.N.; Shad, F. Integration, implementation and reporting outlooks of sustainability in higher education institutions (HEIs): Index and case base validation. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 22, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawashdeh, A.M. The impact of green human resource management on organizational environmental performance in Jordanian health service organizations. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 10, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, D.; Tilt, C.; Xydias-Lobo, M. Sustainability reporting by publicly listed companies in Sri Lanka. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Volume 17, pp. 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Vanderplas, J. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, F.; Bagdadli, S.; Camuffo, A. The HR role in corporate social responsibility and sustainability: A boundary-shifting literature review. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, K.; Kartha, S. Land-based negative emissions: Risks for climate mitigation and impacts on sustainable development. Int. Environ. Agreements: Politi- Law Econ. 2018, 18, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk, M. Multiple Levels of Corporate Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, V.; Wesselink, R.; Studynka, O.; Kemp, R. Encouraging sustainability in the workplace: A survey on the pro-environmental behaviour of university employees. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. Green HRM—A Key for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Res. Manag. 2018, 8, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gholami, H.; Rezaei, G.; Saman, M.Z.M.; Sharif, S.; Zakuan, N. State-of-the-art Green HRM System: Sustainability in the sports center in Malaysia using a multi-methods approach and opportunities for future research. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.A.; Opatha, H.H.D.N.P.; Nawaratne, N.N.J. Employee green performance of job: A systematic attempt towards measurement. Sri Lankan J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooranloo, H.S.; Azadi, M.H.; Sayyahpoor, A. Analyzing factors affecting implementation success of sustainable human resource management (SHRM) using a hybrid approach of FAHP and Type-2 fuzzy DEMATEL. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.; Bon, A.T. The impact of green human resource management and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.A.; Opatha, H.H.D.N.P. Analytical and Theoretical Perspectives on Green Human Resource Management: A Simplified Underpinning. Int. Bus. Res. 2016, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Green Human Resource Management: Policies and practices. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2015, 2, 1030817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolăescu, E.; Alpopi, C.; Zaharia, C. Measuring Corporate Sustainability Performance. Sustainability 2015, 7, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H. Assessing organizations performance on the basis of GHRM practices using BWM and Fuzzy TOPSIS. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 226, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddi, H. Triple Bottom Line and Sustainability: A Literature Review. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2015, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I.; Parsa, S.; Roper, I.; Wagner, M.; Muller-Camen, M. Reporting on sustainability and HRM: A comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world’s largest companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, S.A.; Phil, M. Effects of Green Human Resources Management on Firm Performance: An Empirical Study on Pakistani Firms. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 8, 2222–2839. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L. Green human resource management and green supply chain management: Linking two emerging agendas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibarras, L.D.; Coan, P. HRM practices used to promote pro-environmental behavior: A UK survey. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 2121–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Carollo, L. A paradox view on green human resource management: Insights from the Italian context. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 27, 212–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donohue, W.; Torugsa, N. (Ann) The moderating effect of ‘Green’ HRM on the association between proactive environmental management and financial performance in small firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 27, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, S.K.; Othman, M. The impact of green human resource management practices on sustainable performance in healthcare organisations: A conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The Drivers of Greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, S.R.; Joshi, A.W. Corporate Ecological Responsiveness: Antecedent Effects of Institutional Pressure and Top Management Commitment and Their Impact on Organizational Performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2011, 22, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Safwan, N.; Usman, A.; Adnan, A. Green HRM as predictor of firms’ environmental performance and role of employees’ environmental organizational citizenship behavior as a mediator. J. Res. Rev. Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 699–715. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, K.E.; Estrin, S.; Bhaumik, S.K.; Peng, M.W. Institutions, resources, and entry strategies in emerging economies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 30, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calia, R.C.; Guerrini, F.M.; De Castro, M. The impact of Six Sigma in the performance of a Pollution Prevention program. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B.F.; Huang, S.C. Achieving sustainability through attention to human resource factors in environmental management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel Influences on Voluntary Workplace Green Behavior: Individual Differences, Leader Behavior, and Coworker Advocacy. J. Manag. 2014, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykan, E. Gaining a Competitive Advantage through Green Human Resource Management. In Corporate Governance and Strategic Decision Making; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opatha, H.H.D.N.P.; Arulrajah, A.A. Green Human Resource Management: Simplified General Reflections. Int. Bus. Res. 2014, 7, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.A.; Opatha, H.H.D.N.P.; Nawaratne, N.N.J. Green human resource management practices: A review. Sri Lankan J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 5, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Environmental Performance: An Employee-Level Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, N.; Abdulrahman, M.D.; Wu, L.; Nath, P. Green competence framework: Evidence from China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Gupta, N. Green HRM: An Innovative Approach to Environmental Sustainability. Proceedings of Twelfth AIMS International Conference on Management, Kozhikode, India, 2–5 January 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tomšič, N.; Bojnec, Š.; Simčič, B. Corporate sustainability and economic performance in small and medium sized enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Zahid, M. Naveed Impact of Information Technology on E-Banking: Evidence from Pakistan’s Banking Industry. Abasyn J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 4, 241–263. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid, M.; Jehangir, M.; Shahzad, N. Towards Digital Economy. Int. J. E-Entrep. Innov. 2012, 3, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Partial Least Squares: Regression & Structural Equation Models; Statistical Associates Publishing: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, F.H., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Employees’ green recovery performance: The roles of green HR practices and serving culture. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1308–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, M.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, K.-K.; Saarinen, T.; Tuunainen, V.; Wassenaar, A. A cross-cultural study on escalation of commit-ment behavior in software projects. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 78.57 |

| Female | 21.43 | |

| Age | 20 or fewer years old | 14.28 |

| 21–30 years old | 41.18 | |

| 31–40 years old | 31.93 | |

| 41–50 years old | 12.61 | |

| Education | Bachelor | 37.39 |

| Master’s Degree | 55.04 | |

| MPhil | 5.88 | |

| Ph.D. and Above | 1.68 | |

| Experience | 1–5 years | 14.71 |

| 6–10 years | 27.73 | |

| 11–15 years | 22.69 | |

| 16–20 years | 18.49 | |

| 20 or above years | 16.39 | |

| Position | Entry Level | 21.43 |

| Intermediate Level/Experience Level | 40.76 | |

| Line Management | 11.34 | |

| Middle Management | 10.50 | |

| Senior Management | 15.97 | |

| Sectors | Industrial | 27.31 |

| Banking | 23.11 | |

| Education—Universities | 24.79 | |

| Information Technology (IT) | 24.79 |

| Loadings | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Sustainability (CS) | - | 0.840 | 0.516 |

| CS2 | 0.744 | - | - |

| CS3 | 0.745 | - | - |

| CS4 | 0.760 | - | - |

| CS5 | 0.540 | - | - |

| CS7 | 0.775 | - | - |

| Green Involvement (GI) | - | 0.846 | 0.524 |

| GI1 | 0.687 | - | - |

| GI2 | 0.717 | - | - |

| GI4 | 0.792 | - | - |

| GI5 | 0.695 | - | - |

| GI6 | 0.722 | - | - |

| Green Pay and Reward (GPR) | - | 0.830 | 0.621 |

| GPR1 | 0.799 | - | - |

| GPR2 | 0.848 | - | - |

| GPR3 | 0.709 | - | - |

| Green Recruitment and Selection (GRS) | - | 0.822 | 0.615 |

| GRS1 | 0.855 | - | - |

| GRS2 | 0.901 | - | - |

| GRS3 | 0.651 | - | - |

| Green Training (GT) | - | 0.827 | 0.615 |

| GT1 | 0.803 | - | - |

| GT2 | 0.740 | - | - |

| GT3 | 0.808 | - | - |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Sustainability (1) | 0.718 | - | - | - | - |

| Green Involvement (2) | 0.687 | 0.724 | - | - | - |

| Green Pay and Reward (3) | 0.679 | 0.663 | 0.788 | - | - |

| Green Recruitment and Selection (4) | 0.650 | 0.666 | 0.672 | 0.784 | - |

| Green Training (5) | 0.631 | 0.718 | 0.667 | 0.694 | 0.784 |

| Construct | Adj. RSqr | f2 | Q2 | VIF | SRMR | NFI | rms Theta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Involvement | - | 0.089 | 0.023 | 2.383 | - | - | - |

| Green Pay and Reward | - | 0.039 | 0.011 | 2.264 | - | - | - |

| Green Recruitment and Selection | - | 0.082 | 0.026 | 2.597 | - | - | - |

| Green Training | - | 0.005 | 0.000 | 2.756 | - | - | - |

| Corporate Sustainability | 0.578 | - | - | - | 0.073 | 0.736 | 0.198 |

| Structural Paths | Std Beta | Std Error | t-Value | p-Values | 95% CI LL | 95% CI UL | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI > CS | 0.308 | 0.078 | 3.945 | 0.000 ** | 0.165 | 0.480 | H1 Supported |

| GPR > CS | 0.296 | 0.069 | 4.295 | 0.000 ** | 0.151 | 0.427 | H2 Supported |

| GRS > CS | 0.199 | 0.069 | 2.874 | 0.004 * | 0.065 | 0.339 | H3 Supported |

| GT > CS | 0.068 | 0.100 | 0.673 | 0.501 | –0.135 | 0.273 | H4 Not Supported |

| Industrial - Banking | Path Coefficients-Diff (Industrial - Banking) | p-Value Original 1-Tailed (Industrial vs Banking) | p-Value New (Industrial vs Banking) | p-Value (Parametric Test) | p-Value (Welch–Satterthwaite Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI > CS | 0.112 | 0.344 | 0.688 | 0.625 | 0.667 |

| GPR > CS | 0.025 | 0.451 | 0.903 | 0.897 | 0.907 |

| GRS > CS | –0.627 | 0.968 | 0.064 | 0.010 | 0.047 |

| GT > CS | 0.398 | 0.119 | 0.238 | 0.193 | 0.239 |

| Industrial - IT | Path Coefficients-diff (Industrial vs. Banking) | p-Value original 1-tailed (Industrial vs. Banking) | p-Value new (Industrial vs. Banking) | p-Value (Parametric Test) | p-Value (Welch–Satterthwaite Test) |

| GI > CS | 0.535 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.006 |

| GPR > CS | 0.109 | 0.285 | 0.57 | 0.574 | 0.611 |

| GRS > CS | –0.232 | 0.879 | 0.243 | 0.2 | 0.253 |

| GT > CS | –0.435 | 0.957 | 0.087 | 0.073 | 0.071 |

| Industrial - Education | Path Coefficients-diff (Industrial vs. Banking) | p-Value original 1-tailed (Industrial vs Banking) | p-Value new (Industrial vs Banking) | p-Value (Parametric Test) | p-Value (Welch-Satterthwaite Test) |

| GI > CS | 0.067 | 0.338 | 0.675 | 0.677 | 0.671 |

| GPR > CS | 0.144 | 0.139 | 0.278 | 0.29 | 0.285 |

| GRS > CS | –0.342 | 0.995 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| GT > CS | 0.024 | 0.464 | 0.929 | 0.906 | 0.901 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jamal, T.; Zahid, M.; Martins, J.M.; Mata, M.N.; Rahman, H.U.; Mata, P.N. Perceived Green Human Resource Management Practices and Corporate Sustainability: Multigroup Analysis and Major Industries Perspectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063045

Jamal T, Zahid M, Martins JM, Mata MN, Rahman HU, Mata PN. Perceived Green Human Resource Management Practices and Corporate Sustainability: Multigroup Analysis and Major Industries Perspectives. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063045

Chicago/Turabian StyleJamal, Tauseef, Muhammad Zahid, José Moleiro Martins, Mário Nuno Mata, Haseeb Ur Rahman, and Pedro Neves Mata. 2021. "Perceived Green Human Resource Management Practices and Corporate Sustainability: Multigroup Analysis and Major Industries Perspectives" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063045

APA StyleJamal, T., Zahid, M., Martins, J. M., Mata, M. N., Rahman, H. U., & Mata, P. N. (2021). Perceived Green Human Resource Management Practices and Corporate Sustainability: Multigroup Analysis and Major Industries Perspectives. Sustainability, 13(6), 3045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063045