Abstract

The purpose of this study is to explore the relation between personality traits and the level of aspiration to acquire new skills and improve one’s competence in the midst of first employment. Although with mixed results, previous studies indicated that personality attributes influence goal orientation, both in the school and work settings. However, there have not been any studies that have specifically analysed this relation in the context preceding the first employment. The results of this research, on a sample of last-semester business administration students of an esteemed mid-European university, indicate that prior to the first employment, two personality traits—openness to new ideas and disposition to negative emotions—influence the level of motivation to acquire knowledge and novel modes of action. Insight into the antecedents of an individual’s orientation towards increasing and developing competencies prior to the first employment is an important topic for organizations who have the imperative to develop more sustainable knowledge management practices in an early stage of organizational socialization.

1. Introduction

Smooth integration of new employees in existing organizational dynamics is one of the pivotal elements of organizational development. The sine qua non of successful integration are the necessary skills and knowledge that newcomers possess as well as their personality and their commitment to organizational goals. This paper is focused on the relationship between the level of desire to acquire new skills and improve one’s competence and personality traits. Previous research focused on the relation between employees’ personality and orientation to learning in the work setting [1,2] and school setting [3]. However, in this paper, we suggest that special attention should be given to addressing the relation between attitudes towards learning motivation and personality in the time preceding the first employment.

Understanding determinants of individuals ambitions at the beginning of their careers can set the tone to the way in which the integration of newcomers is conducted and enables optimal engagement of each individual during this key segment of organizational socialization. On a more general level, identifying employees’ mindset in relation to goal orientation and commitment allows firms to effectively manage employees’ performance. That is so because goal orientation drives the development of dynamic organizational capabilities, such as market orientation and innovativeness. Answering this question is important because the individual’s learning goal orientation in early stages of organizational socialization sets the tone for the successful integration of newcomers into an organization, which consequently impacts organizational efficiency. Since knowledge is also a key ingredient of sustainable competitiveness, understanding employee’s proclivity to learn is of importance in developing adequate knowledge management practices.

Through the education process, students begin to realize their strengths and weaknesses, out of which they constitute expectations with respect to career development. One of the aspects of career development is their inclination to learn and develop their competencies in their future job. This important factor in future career development can be viewed through the construct of learning goal orientation, which focuses on intrinsic motivation to obtain mastery over segments of their work. People with a high learning goal orientation want to demonstrate high abilities or want to avoid demonstrating a lack of competence, primarily to themselves. Although the problem of learning goal orientation can be tackled from multiple perspectives, we hypothesize that personality traits have a significant role in the matter.

Personality as a problem area in organizational research is a well-established theme, covering multiple facets of organizational dynamic. Most individual differences in human personality can be classified into five broad empirically derived domains: extraversion—indicating how outgoing and social a person is; openness to experience—representing the level of intellectual curiosity and creativity; emotional stability—the tendency to remain stable and balanced in challenging situations; conscientiousness—the tendency to be responsible, hard-working, and to adhere to norms and rules; and agreeableness—indicative of friendliness, and tactfulness in communication.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Two Facets of an Individual’s Goal Orientation

The concept of goal orientation theory originated in achievement motivation theory [4] and refers to an individual’s disposition of goal achievement preferences. The concept emerged in the 1980s and today is considered to be a prominent research framework in organizational psychology and organizational behaviour [5].

The early studies commonly distinguished two forms of goal orientation: learning goal orientation (also called mastery), which is defined in terms of a focus on learning, mastering the task according to self-set standards or self-improvement, and performance goal orientation, which represents a focus on demonstrating competence or ability as well as on the question how ability will be judged relative to others [6,7]. Individuals holding a performance goal orientation want to demonstrate and validate their competences and prefer situations where they can compare their competences to the competences of others [8,9,10]. Compared to that, individuals who hold a learning goal orientation want to increase and develop their competences [8,10]. More recent works of goal theorists have incorporated a second dimension of goal orientation—approach and avoidance [11,12,13]—which corresponds to individuals’ positive or negative motivation to receive a favourable judgment from others.

The implications of goal orientation theory to organizational research are numerous [14,15]. By understanding goal orientation, psychologists identified links from learning and performance goals to the motivational elements of persistence, intensity, and choice in work behaviour [16,17]. A pioneering study led by Sujan, Weitz, and Kumar [18] was first to model the inter-related links between feedback, goal orientation, work behaviour, and performance among U.S. salespeople. This effort was followed in similar studies by Kohli et al. [19] and VandeWalle et al. [10]. In a comprehensive overview of goal orientation theory, Button, Mathieu, and Zajac [8] discuss the importance of goal orientation as a multidimensional construct in organizational research and suggests recommendations for further research. Since that time, the theory had many applications in connection with several different organizational issues.

Lee, Tan, and Javlgi [20] investigated the effects of learning and performance goals on different facets of organizational commitment and how these effects impact individuals’ job outcomes. Their results indicate that, while learning goal orientation is related to the three components of organizational commitment—affective, normative, and continuance—the performance goal is only related to affective commitment. Chadwick and Raver [21] investigated how individuals’ motivation for different goals achievement, that is, goal orientations, shape the way they individually and collectively participate in organizational learning processes. Similarly, Li and Tsai [22] addresses the issue of goal orientation with respect to organizational learning in the context of SMEs. With respect to the approach and avoidance dimensions of goal orientation, research has shown that learning goal orientation tends to have the most beneficial effects on performance outcomes whereas avoid-performance goal orientation tends to have the most detrimental effects on performance outcomes (e.g., [23]).

A significant body of literature can be found regarding the connection between goal orientation and creativity. For instance, Bakker at al. [24] were looking at the role of goal orientation on work engagement and creativity and found that learning goal orientation strengthened, and performance goal orientation weakened, the links between proactive management and engagement, and between engagement and creativity. Similarly, research on goal orientation (both learning and performance orientation) profiles in work contexts, conducted by Nerstad, Richardsen, and Roberts [25] on a big sample of more than 8200 engineers and technologists, noted that learning and performance climates are relevant antecedents of employees’ goal orientation profiles.

The idea of goal orientation is a fundamental part of a wider term “ambition”. For instance, Barsukova [26] identifies seven groups of the psychological characteristics of ambition: goals, achievement motivation, self-attitude, attitude to other people, attitude to professional activity, self-regulation, and cognitive characteristics. The connection between goal orientation and ambition is especially vivid in the case of performance goal orientation where individuals wish to demonstrate high abilities on the outside, within the social hierarchy of their choosing.

2.2. Differences in Personality and Major Personality Traits

The issue of differences in personality was a matter of research interest from the beginnings of psychoanalysis. Jung [27], Allport et al. [28], Cattell [29], Eysenck and Eysenck [30], and many more after them have dwelled on the subject in different ways. Most researchers in the area agree that personality is best conceptualized in terms of a five-factor model (called the Big-Five model), including the dimensions of extraversion, openness to experience, neuroticism, conscientiousness, and agreeableness [31,32]. The Big-Five framework suggests that most individual differences in human personality can be classified into these five broad, empirically derived domains [33]. Each factor is described in bipolar terms (e.g., extraversion vs. introversion) and also summarizes several more particular aspects (e.g., trustfulness), which, in turn, subsume a large number of even more specific facets (e.g., calm, suspicious).

Extraversion is the personality trait that depicts straightforward people, who do not mind arguing their opinions, interacting in a forthright way, and who seek stimulation [34]. A person high on extraversion has a tendency to be sociable [35]. On the other hand, a person who is more reserved, less likely to be social, and tends to be uncomfortable with interacting with strangers is termed as an introverted person [31]. Research suggests that extraversion is personality dimension that is a good predictor of career success [36].

Agreeableness is a personality trait that holds people to be accommodating and helping [34]. Individuals who have a high level of agreeableness create win–win situations by their flexible attitude [29]. These traits help one to negotiate and maintain balance [37]. More agreeable individuals have a propensity to attain cooperation and social harmony [31]. On the other hand, people who rank low on this personality trait tend to be selfish, not caring towards other people’s concerns, and, as such, believe that others are also working on their personal motive and for that reason they are likely to be less inclined to build relationships based on trust [31].

Conscientiousness have a positive influence on career success in any organization [36]. A conscientious person tends to be very careful about their future plans [34]; they are cautious about their surroundings, compact, and fully scheduled [29]. Conscientiousness encompass traits like reliability, perseverance, dependability, and hard work [38]. People ranking low on this trait will be careless about their work, not inclined to work in a concise way, and who would assure their work to be free of faults [31].

Openness to experience is a trait that allows us to reconfigure a situation in different ways [29] and enables us to have deductive ability to analyse problems [37]. People with a low score for openness to experience tend to be more conventional in their problem-solving approach and do not try to be explorative in finding new ways to solve a particular problem [34]. They also tend to dislike change and prefer well known routines [31].

Neurotic individuals are easily trapped by stress and tend to be emotional and anxious. They often feel hopeless and frustrated when showing their feelings and exhibiting their behaviours [39]. This personality type is prone to mental disorder and depression [34], which may have a serious impact on their physical and psychological health [31]. On the other hand, people who rank low in this personality trait are more optimistic, emotionally stable, seem to be mature, and not likely to overreact in stressful environments [29].

3. Research Sample and Design

3.1. Data Collection and Descriptive Statistics

The participants of the research were graduate students enrolled in the last year of a business administration program in a large mid-European university. The data was collected in two iterations, the first one in 2019 and the second in 2020 (total N = 223).

Students were asked two sets of questions. The first set of questions concerned their focus on learning with respect to the experience in the school setting and their expectation about work surroundings; the second set regarded an assessment of their personality types. The sample details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

As shown in Table 1, most of the respondents are women (65.92%). The vast majority of our sample ranges between ages 20 and 25 (76.68%), and few of them are over 30 years old. Additionally, there are five focus areas of the student’s business administration education: finance, general management, marketing, accounting, and managerial informatics. Relatively, the biggest part of the sample falls into the category of a major in finance (32.73%), although general management, marketing, and accounting also have significant representation (ranging from 16.15% up to 27.35%).

3.2. Instruments

The learning goal orientation metrics are reasonably well established in the case of work surroundings [10,15,40]; however, we argue that the context that we are interested in, finishing of university education and prior to first employment, calls for a slightly different approach. Although educational settings are to some extent goal oriented, in the sense of finishing the classes and graduating they are much less so than work surroundings with precisely set goals and pressure arising from committing results to other organizational members. Prior to the first employment, students have limited experience in goal-oriented organizational dynamics and we argue that the instrument that would adequately measure their learning goal orientation should be based on their own experiences in school surroundings and on their attitudes towards expected learning goal orientation in their future work. As a basis for our construct of learning goal orientation prior to first employment, we have used multi-item scales modified from Ames and Archers [41], which deals with a subject’s learning goal orientation in school surroundings, and from Sujan, Weitz, and Kumar [18], aimed at the expectations of the learning achievements in the work environment.

Ames and Archer studied how specific motivational processes are related to the salience of learning and performance goals on a sample of 176 students attending a junior high/high school for academically advanced students. In this research they have used 19 items that constituted learning goal orientation. These items could not be readily used in our research since their focus was on goal orientation in school surroundings. However, the authors also identified eight theoretical distinctions of learning goal orientation in the classroom climate, out of which they have constructed the 19 items used in the research [41]. Based on those distinctions, we have developed a set of questions to asses these characteristics from the student’s perspective prior to their first employment. The questions were focused on the following dimensions: (1) success defined as improvement; (2) placing value on effort; (3) challenges as reasons for satisfaction; (4) teacher’s orientation to how students are learning; (5) viewing of errors/mistakes as part of learning; (6) focus of attention as a process of learning; (7) learning something new as reasons for effort; and (8) progress as evaluation criteria.

Since we have observed learning goal orientation attitudes prior to the first employment, in the development of the research construct, besides school surroundings we have also included work-related expectations. The questions were posed in such a form to allow students to make assumptions on their level of learning goal orientation in their future work environment. The structure of this scale was similar to the instrument used to assert learning goal orientation in school settings but with one important difference—it was not based on experience but on the expectations of what future work would look like from the perspective of learning goal orientation. So, instead of asking the research subjects if they agree or disagree with the importance of the learning goal orientation statements, we have asked them to think whether their response with respect to learning goal orientation would yield satisfactory results in their work. The formulations of the questions were such to make students think about the utility of learning goal orientation in their jobs; for instance, one question stated, “In your opinion, would an approach to continually improve work skills be an important part of being a good employee?”. To operationalize this approach, we have used the multi-item scale from Sujan, Weitz, and Kumar [18], who investigated learning goal orientation as a motivational influence that guide salespeople’s behaviour. The research included 190 sales managers from eight firms across different sectors. Salespeople’s motivational orientation to improve their ability and skills was measured with a nine-item scale out of which we have taken seven items and modified it for our context. The selected items focus on (1) continually improving work skills, being an important part of being a good employee; (2) satisfaction with work well done; (3) making mistakes as a part of a learning process; (4) learning from each experience; (5) the worthiness of spending a great deal of time learning new approaches to deal with job requirements; (6) learning how to be good at a job as being of fundamental importance; and (7) putting in a great deal of effort sometimes in order to learn something new. The two items used in Sujan, Weitz, and Kumar’s research that were discarded for our purpose where the questions (1) “There really are not a lot of new things to learn about selling” (reversed), and (2) “I am always learning something new about my customer”, since they are context specific in the work environment.

The construct for measurement of learning goal orientation consisted of fifteen claims (an eight-claims scale for learning orientation in school settings and seven-claims scale for expected learning goal orientation at work). Each claim was presented as a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” for school learning orientation and “much worse” to “much better” for expected learning orientation at work, which defined the score range from a minimum of 15 to maximum of 75.

The learning goal orientation results were clustered in three segments: a low score, ranging from 15 to 35 points; a medium score, which consisted of scores between 35 and 55 points; and a high score, ranging from 55 to 75 points. Since the learning goal orientation is a self-evaluation construct, and since the participants in the research were students with little experience in organizational work, an objective presumption of misunderstanding of the concepts can be posed. In order to tackle this possibility, besides the measurement scales, the respondents were asked to position themselves in one of the three groups, designated as low, middle, and high level of learning goal orientation. These responses were than compared with the grouping based on the observed level of learning goal orientation. In 6 out of 223 cases (2.7%), the observed learning goal orientation and respondent’s assessment was not congruent. In each of the 6 cases, the respondents claimed to be more learning oriented than their achieved score suggested.

The most comprehensive instrument developed to measure the Big-Five dimensions is the 240-item NEO Personality Inventory developed by Costa and McCrae [42]. This instrument permits measurement of the five personality domains together with six detailed aspects within each dimension. However, the fact that it takes about 50 min to complete makes it hard to use for research purposes. The two other well-established and more widely used research instrument are the 44-item Big-Five Inventory (BFI) [43], as well as the scale developed by Goldberg [31], comprising 100 trait descriptive adjectives (TDA). However, even those instruments proved to be overly extensive (taking around 15 and 25 min, respectively) for use in research settings where time is an important factor. In response to the need for a very brief personality measure, a 10-item inventory (TIPI) was developed and evaluated by Gosling, Rentfrow, and Swann [33]. Since the psychometric properties of a brief personality test proved to be good, additional instruments were developed, including the Single-Item Measure of Personality (SIMP) [44,45]) as well as another 10-item measure developed by Rammstedt and John [46].

Since evaluation of the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) suggested that briefer instruments can stand as reasonable proxies for longer Big-Five instruments, and since the time that it will take responders to finish the survey was a significant factor due to the fact that we had limited time with the students and wanted to make sure they stay concentrated on the task at hand, we have selected this personality scale for our purpose.

The goal of our research was to comprehend whether each of the personality factors influence learning goal orientation. To achieve this goal, we have used one-way analysis of variance: differences in personality types with respect to their learning goal orientation (N = 223). Since the previous larger studies on distribution of personality factors research show that a normal distribution can be applied in cases where subjects’ scores do not perfectly conform to a normal distribution (in this case the data is skewed to the left side of distribution), we will be treating personality factors as continuous data [47,48].

With respect to the particular personality traits and one’s learning orientation, we hypothesize that the higher levels of the personality traits openness to experience, associated with the level of proclivity to intellectual stimulation, will indicate higher levels of learning goal orientation. A case also can be made that the same can be expected for each of the following three personality traits: extraversion, neuroticism, and conscientiousness. However, in this specific context of engagement with the goal-oriented organizational dynamics for a first time, the same can be claimed for the opposite poles of these traits. The trait extraversion, indicating sociability of a person, suggests a more action-oriented individuals but that does not have to indicate desire for acquisition of knowledge as a result of the interaction. The same case actually can be made for the opposite side of this personality trait—introverts tend to be more interested in things than in people, but that does not indicate that the time spend in solitude will be oriented towards learning, especially in the context we are interested in. The personality trait dealing with the level of emotional stability, usually described by its opposite—the level of neuroticism—could also be indicative of an individual’s propensity to learn new things, since this trait is characterized by a high threat awareness. However, in the context of anticipation of the first employment, the expected necessity of adaptation of novel patterns of action can prove to be a trigger of negative emotions, which will consequently diminish one’s learning goal orientation. The same can be said for the personality traits conscientiousness, which represents a tendency to be responsible, boundary focused, and hard working. Although sometimes acquisition of knowledge can be used to deal with the task in hand, it is not the case in every situation. School surroundings, in most cases, appreciate well-grounded and confirmed strategies. Focusing on the novel approaches to finish the task can sometimes even hinder work efficiency, which would not be a good option for a highly conscientious person. Finally, we hypothesise that, of the all personality traits, agreeableness, which demonstrates warmness, friendliness, and tactfulness, is least likely to be connected with the learning goal orientation prior to the first employment.

Although somewhat inferior to the more extensive personality measures, in its evaluation, the Ten-Item Personality Inventory “reached adequate levels in terms of: (a) convergence with widely used Big-Five measures in self, observer, and peer reports, (b) test–retest reliability, (c) patterns of predicted external correlates, and (d) convergence between self and observer ratings” [33]. However, since the instrument is designed to measure very broad domains, with only two items per dimension, we cannot expect high alphas and good fit indices [45]. Actually, the Ten-Item Personality Inventory was designed using criteria that almost guarantee it will perform poorly in terms of alpha and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) or Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) indices. Since the TIPI-s psychometric properties have been thoroughly evaluated as noted, we have focused our efforts to assessment of the measurement model for learning goal orientation.

Construct reliability and convergent and discriminant validity assessments were conducted to evaluate the measurement model for learning goal orientation. Individual Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were tested among the study variables to assess the construct reliability. The values of all construct were greater than 0.7, the acceptance level as suggested by Nunnally and Bernstein [49]. Interestingly, similar to Sujan, Weitz, and Kumar [18], the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for expected work context learning goal orientation was 0.81. Moreover, composite reliability (CR) was tested to confirm the construct reliability as well, with each reaching the 0.7 threshold [49]. Indicator reliability was tested by assess the factor loading of the items. According to Hair et al. [50], a loading greater than 0.5 is acceptable and all items proved to be satisfactory. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) was used to test the convergent validity. The result showed that the values ranged from 0.701 to 0.903, and as such are greater than 0.50, as recommended by Hair, Black, and Babin [51]. In addition, a confirmatory factor analysis was employed to assess the learning goal orientation measurement model validity by comparison of theoretical measurement model with the reality model. The construct of learning goal orientation consisted of two variables, self-evaluation of learning orientation (based on eight items) and self-evaluation of relative learning achievements (based on seven inputs), and is therefore a higher-order factor to those two latent variables. To assess the model fit, two indices were used, the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The measurement model proved to be robust, yielding a CFI of 0.943 and RMSEA of 0.067.

3.3. Data Analysis

For the purpose of data processing, we have used the SPSS program package. The primary method applied for examining the differences in learning goal orientation prior to the first employment with respect to the personality traits of the Big-Five personality model is the one-way analysis of variance.

4. Results

Descriptive results for the set of questions concerning performance goal orientation show that most students exhibit a middle level of learning goal orientation (47.4%), but also that a significant number of subjects have a high level of learning goal orientation (44.7%); in turn, the responses of a very small number of subjects (5.3%) was connected with a low level of learning goal orientation. A tendency to report a high level of learning orientation is not surprising, since the research was done on students who are enrolled in the last year of prestigious business school and as such are by nature competitive and focused on achievement.

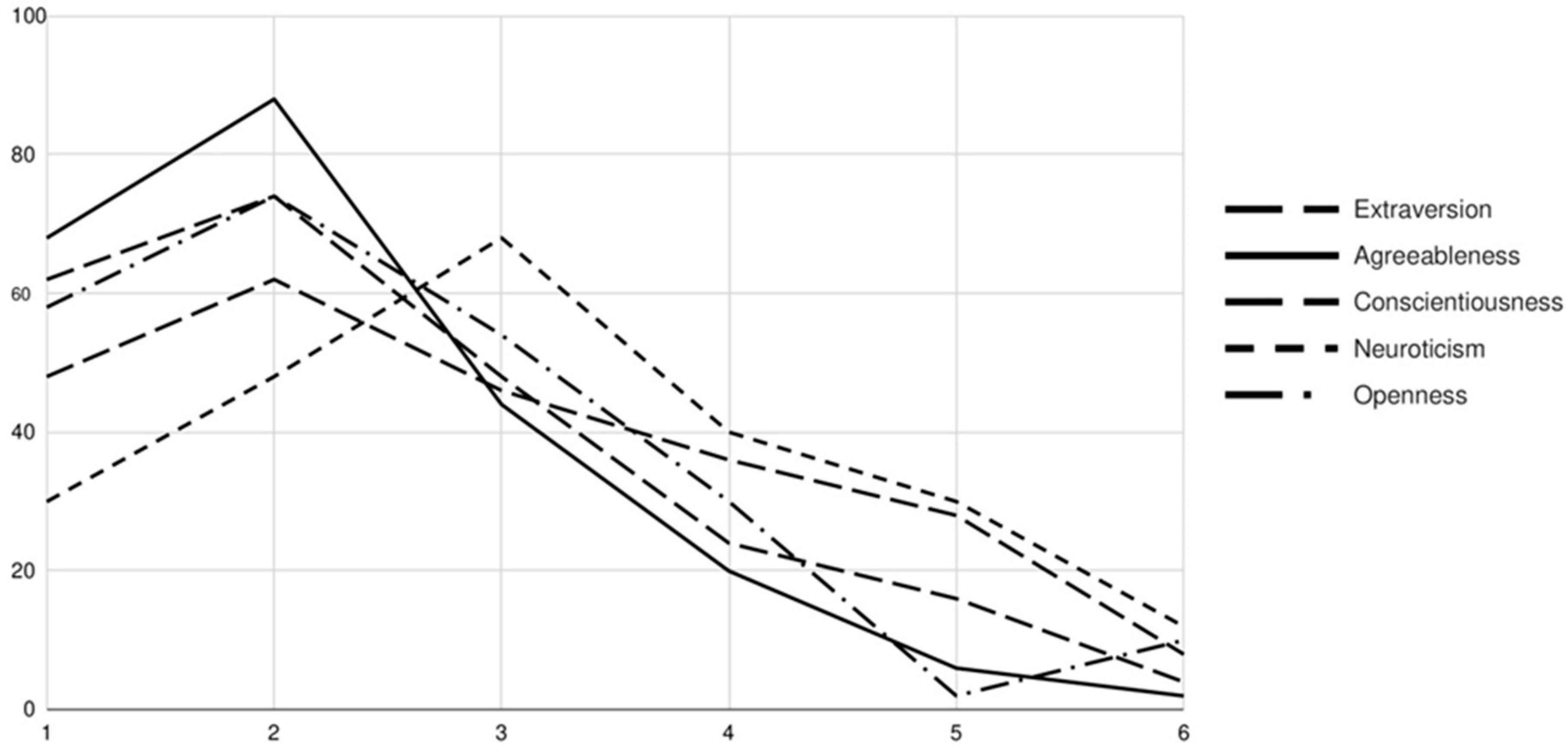

Figure 1 shows the personality inclinations of the students in the research sample, where the horizontal axis shows the measure of each personality trait. For example, in the trait extroversion, a measure of 1 indicates that the subject is highly extroverted while a measure of 6 indicates that the subject is introverted. The vertical axis designates frequencies of the overall number of 223 students that participated in the survey.

Figure 1.

Personality inclinations of the responders in the research sample (N = 223).

From the Figure 1, it can be seen that the distribution of the students’ personality traits is generally positively asymmetric, indicating that more results are grouped around higher values for each trait, with the highest level for agreeableness and the lowest level for neuroticism. According to the personality inclinations, students in the survey are generally more extroverted, meaning that they tend to seek outside affirmation and like dealing with others. From the perspective of the agreeableness personality trait, the research sample mostly consists of individuals who considered themselves as compassionate and approachable. The trait agreeableness showed relatively the highest level. A low level of conscientiousness refers to people who are disorganized, act recklessly, and are not attentive or practical. Only five students out of a total of 223 have characterized themselves by such characteristics. The majority of respondents concern themselves as being highly conscientiousness. With respect to the personality trait neuroticism, most of the subjects in the survey have described themselves as relatively emotionally stable (Level 3) and after that emotionally stable (Level 2), but 20% of the research subjects also designated themselves as relatively emotionally unstable (Level 4), which results in neuroticism being the relatively lowest personality trait in the sample. The trait openness to experience also shows positive asymmetry with more participants who described themselves as willing to explore new options and possibilities.

In order to explore the research problem—an investigation of the differences in learning goal orientation prior to the first employment with respect to the personality traits of the Big-Five personality model—we have used one-way ANOVA (Table 2).

Table 2.

One-way ANOVA: differences in personality types with respect to performance goal orientation (N = 223).

Table 2 shows that no statistically significant difference was obtained between the levels of learning goal orientation and the personality traits extraversion (p < 0.05), agreeableness (p < 0.05), and conscientiousness (p < 0.05). However, it can be seen that the research yielded a statistically significant difference between learning goal orientation and neuroticism (F (2, 108) = 7.49, p = 0.001) as well as a statistically significant difference between the level of learning goal orientation and openness to experience (F (2, 108) = 10.51, p < 0.001). In order to determine between which groups of designated positions there is a statistically significant difference, we have conducted Fishers Least Significant Difference (LSD) post-hoc test. Regarding personality trait openness to experience, a statistically significant difference was obtained between the low and middle group (p = 0.015), middle and high group (p < 0.001), as well as between the middle and high group (p = 0.002). From the perspective of neuroticism, the results showed a significant difference between the lower and middle levels of learning goal orientation (p = 0.007), lower and higher levels (p < 0.001), and between the middle and higher levels (p = 0.04).

5. Discussion

The investigation based on assessment of the learning goal orientation of students prior to their first employment and their personality traits yielded a significant difference between learning goal orientation and the personality traits openness to experience and neuroticism.

Openness to experience proposes a willingness to tackle ideas and initiate novel action patterns. Results on this personality trait shows how participants whose level of learning goal orientation is designated as at a low level achieve higher results on the openness to experience scale (higher result means less openness to experience); i.e., they are more conservative and more inclined to the familiar (M = 4.00; SD = 1.67) compared to the participants at the middle level (M = 2.74; SD = 1.12) and at the high level (M = 2.00; SD = 1.18). Participants whose learning goal orientation was defined as middle also show less openness to experience (M = 2.74; SD = 1.12) compared to participants who claimed the highest level of learning goal orientation (M = 2.00; SD = 1.18). It is not surprising that a disposition to learn and develop competencies shows a connection with the personality trait openness to experience since it is the trait of creative individuals with emphasized conceptual skills.

Neuroticism is proclivity to negative emotions, which is approximated by awareness of possible losses and dangers. The evidence suggests that the students with a higher level of the personality trait neuroticism exhibit a lower level of learning goal orientation. Research subjects who designated their learning goal orientation as low show higher levels of the personality trait neuroticism; that is, they tend to be more prone to emotional stress and anxiety (M = 4.83; SD = 1.17) compared to students who reported their level of learning goal orientation to be at the middle level (M = 3.30; SD = 1.30) as well as the ones who designated their learning goal orientation as the highest (M = 2.76; SD = 1.34). Students who showed to be in the middle level regarding their learning goal orientation also showed higher results in the personality trait neuroticism (M = 3.30; SD = 1.30) with respect to students who demonstrated a high level of learning goal orientation (M = 2.76; SD = 1.34). Although the lack of emotional stability can increase the level of conflict between organizational members and hence diminish organizational effectiveness in the short term, a very low level of neuroticism can also prove to be problematic, since it disables us to perceive latent risks that have potential to undermine our efforts. Our interesting results concerning this personality trait should, however, be taken with a grain of salt. Our construct of learning goal orientation partly relied on self-evaluation of relative learning achievements, which, because it is based on comparison, has the potential to indicate lower levels for more neurotic respondents due to their lower self-confidence.

These results contribute to previous studies that have investigated the relationship between personality traits and goal orientations that, due to different theoretical and measurement models, are difficult to compare and lead to inconsistent results (e.g., [52,53]). Early studies [54,55,56], have explored the “personality” of jobs by examining the relationship between personality and the work or career an individual prefers. Other studies have examined the relationship between personality and career choice [57] or between achievement motivation and career choice [58].

In comparison to our results from previous research, two major differences need to be articulated: the first is that the largest part of the goal orientation research tackle the issue of performance goal orientation instead of learning goal orientation, and that most of them are situated in the work environment.

With respect to our research context, noteworthy research on the relations between the Big-Five personality traits and goal orientation was conducted by McCabe et al. [2], who investigated context-specific achievement goals in two different contexts: school and work. The authors used multilevel modelling with standardized values for both the traits and the goals so that they were able to interpret the results like correlation coefficients. The results across both studies showed how conscientiousness was strongly and positively related to learning-approach goals, agreeableness was positively related to learning-approach goals and negatively related to performance-approach goals, while both avoidance goals and performance goals were positively related to neuroticism. Similarly, in the two samples, for students and full-time employees, Bipp et al. [58] investigated the relationships between personality traits and the preference for job characteristics concerning either extrinsic (job environment) or intrinsic job features (work itself). The results indicate a different motivation on the basis of individual differences, which implies important practical consequences with respect to staffing decisions and the selection of the right motivational techniques for managers. According to this research, two personality traits (openness to experience and core self-evaluations) were consistently found to be positively related to the preference concerning work characteristics.

Several more noteworthy studies were conducted in educational setting. Sorić, Penezić, and Burić [59] examined the relationship between the Big-Five traits, academic motivation, and academic achievement on a sample of high school students. The mediation analysis revealed that for the personality trait conscientiousness, the learning approach, performance approach, and a work-avoidance goal orientation fully mediates the relationship between students’ personality traits and their academic achievement. Lamm et al. [60], on a sample of undergraduate leadership students, also found that openness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability can predict goal orientation. Similarly, the associations between the Big-Five personality dimensions and creativity moderated by learning motivational goal orientation was investigated by Kaspi-Baruch [61]. The results showed how individuals high in extroversion, emotional stability, and low in conscientiousness are most creative when they are oriented toward learning.

The literature also incorporates some evidence of the relationship between a personality and performance goal orientation. In a recent study, Pickett, Hofmans, and Fruyt [1] found that extraversion is associated with lower levels of performance approach goal orientation. These findings suggest that an integrative approach to personality allows a better understanding of the relationship between extraversion and performance approach goal orientation. However, this evidence arguably contradicts [62] previous argumentation that performance goals would lead to learning oriented, challenge-seeking goal-setting behaviour only if a person had confidence in his or her abilities. This raises the issue of how self-efficacy interacts with goal orientation to influence self-set goal levels if we take into consideration that extroversion plays an important part in the process of self-confidence.

There are three limitations of the research that we should point out. The first one is the potential misconception of the respondents on their learning goal orientation in the work setting. Since they are at the beginning of their professional work life, they do not have the experience to test themselves with respect to the claimed level of learning orientation they will demonstrate in the future. Secondly, the research sample included a relatively small number of reports that fall into the category of a low learning goal orientation. Although the difference between the middle and high learning orientation levels proved to be significant as well, the higher relative segment of research subjects who claimed a lower ambition to increase and develop competencies would be preferable. Although the Ten-Item Personality Inventory psychometrics are reasonable and well known, the use of the more extensive and established multi-item instruments can be warranted in situations if more time would be available.

There are several practical implications of our research results. Firstly, a better understanding of the relation between personality traits and students learning goal orientation prior to their first employment can give incentive to university counselling services that rely heavily on accessing and processing information that their students give them on the matters of competencies, positive attitudes, and coping behaviours. Secondly, the issue of attitude towards learning goal orientation can be, among other issues, useful in the selection process. We also argue that the results can contribute to the facilitation of adequate organizational socialization of newcomers.

6. Conclusions

Even beyond goal-driven organizational dynamics, the focus on learning has many benefits. As the German philosopher Lessing puts it, “The true value of a man is not determined by his possession, supposed or real, of Truth, but rather by his sincere exertion to get to the Truth.” [63]. In organizations, likewise, individuals who are oriented towards knowledge acquisition and who can incorporate new knowledge into solving the existing organizational problems are very valuable organizational assets, since knowledge acquisition is the fundamental resource of long-term competitive advantage.

The ambition to increase and develop competences can move into one’s focus in any stage of life but arguably it is most emphasized during the time of learning, including institutional education and practical, on-site learning. A specific period in this respect is time prior to first employment, where future employees are supposed to cross from theory to practice. Bridging this gap can prove to be an unpleasant experience for future employees but also for organizations whose suboptimal approach with respect to individual learning orientation can hinder the socialization of newcomers.

In our research, we have connected this proclivity to learning with personality, a well-established and proven concept in the organizational development literature. Since the research on influences of personality on numerous organizational issues is abundant, our research on connection with learning goal orientation gives novel insight into the rich body of organizational literature in the domain of personality.

Our findings indicate two important issues. First is that responders with a higher level of the personality trait openness to experience exhibit a higher level of learning goal orientation. Openness to new ideas and a willingness to engage in activities that one has not experienced before is the most important entrepreneurial trait; it fosters the development of conceptual skills, which are very hard to learn and also very valuable in many work settings, especially in contemporary business models. On the other hand, respondents with higher levels of the personality trait neuroticism show more modest levels of learning goal orientation. Proclivity to negative emotions, which is described by the personality trait neuroticism, is connected to an intensive response to stressors and more likely an interpretation of ordinary situations as threatening. Both of these findings can be starting points for more detailed studies of the antecedents and consequences of the connection between openness to experience and neuroticism and learning goal orientation.

Furthermore, while both performance and learning goal orientation in an organizational setting are reasonably well-investigated problems, the context of students at the begging of their professional path lacks research insight. This research context can hopefully attract more research attention since, in our opinion, a better understanding of an individual’s attitudes preceding the first employment can help organizations to develop more sustainable knowledge management practices in the early stage of organizational socialization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, and visualization, M.D.L., D.H., V.S.; writing—review and editing, and supervision, D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pickett, J.S.; Hofmans, J.; Fruyt, F. Extraversion and performance approach goal orientation: An integrative approach to personality. J. Res. Personal. 2019, 82, 103846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, K.O.; Van Yperen, N.W.; Elliot, A.J.; Verbraak, M. Big Five personality profiles of context-specific achievement goals. J. Res. Personal. 2013, 47, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bipp, T. What do people want from their jobs? The Big Five, core self-evaluations and work motivation. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2010, 18, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D.C.; The Achieving Society. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1496181 (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Don Vandewalle, C.; Nerstad, G.; Dysvik, A. Goal Orientation: A Review of the Miles Traveled and the Miles to Go. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2019, 6, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, E.S.; Dweck, C.S. Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Leggett, E.L. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 95, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, S.B.; Mathieu, J.E.; Zajac, D.M. Goal orientation in organizational research: A conceptual and empirical foundation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 67, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.G. Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychol. Rev. 1984, 91, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewalle, D. Development and Validation of a Work Domain Goal Orientation Instrument. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1997, 57, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Covington, M.V. Approach and Avoidance Motivation. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 13, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Harackiewicz, J.M. Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, G.D.; Dweck, C.S. Achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: Their relation and their role in adaptive motivation. Motiv. Emot. 1992, 16, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, J.L.; Hofmann, D.A.; Ringenbach, K.L. Goal orientation and action control theory: Implications for industrial and organizational psychology. Int. Rev. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 1993, 8, 193–232. [Google Scholar]

- van Dam, K. Workplace Goal Orientation. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 31, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.P.; Pritchard, R.D. Motivation Theory in Industrial and Organisational Psychology. In Handbook of Industrial and Organisational Psycholog; Dunnette, M.D., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1987; pp. 63–130. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. Human Motivation; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sujan, H.; Weitz, B.A.; Kumar, N. Learning Orientation, Working Smart and Effective Selling. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A.K.; Shervani, T.A.; Challagalla, G.N. Learning and Performance Orientation of Salespeople: The Role of Supervisors. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.F.; Tan, J.A.; Javalgi, R. Goal orientation and organizational commitment: Individual difference predictors of job performance. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2010, 18, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, I.C.; Raver, J.L. Motivating Organizations to Learn: Goal Orientation and Its Influence on Organizational Learning. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 957–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.C.; Tsai, C.Y. Antecedents of Employees’ Goal Orientation and the Effects of Goal Orientation on E-Learning Outcomes: The Roles of Intra-Organizational Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S.C.; Youngcourt, S.S.; Beaubien, J.M. A meta-analytic examination of the goal orientation nomological net. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 128–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Petrou, P.; Op den Kamp, E.M.; Tims, M. Proactive Vitality Management, Work Engagement, and Creativity: The Role of Goal Orientation. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 69, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerstad, C.G.L.; Richardsen, A.M.; Roberts, G.C. Who are the high achievers at work? Perceived motivational climate, goal orientation profiles, and work performance. Scand. J. Psychol. 2018, 59, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsukova, O.V. Psychological characteristics of ambitious person. J. Process Manag. New Technol. 2016, 4, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.G. Memories, Dreams, Reflections; Vantage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G. Personality: A Psychological Interpretation; Holt, Rinehart, & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, H.; Mead, A. The sixteen personality factor questionnaire (16pf). In The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment: Volume 2—Personality Measurement and Testing; Boyle, G.J., Matthews, G., Saklofske, D.H., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2008; pp. 135–159. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, H.J.; Eysenck, S.B.G. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire: (EPQ-R Adult); EdITS/Educational and Industrial Testing Service: San Diego, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, L.R. The development of markers for the Big-five factor structure. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. A five-factor theory of personality. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; Pervin, L.A., Johns, O.P., Eds.; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B., Jr. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, G.S.J.; Anderson, N. Personality as a Predictor of Work Related Behavior and Performance: Recent Advances and Directions for Future Research. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Hodgkinson, G.P., Ford, J.K., Eds.; Whiley: London, UK, 2008; pp. 261–305. [Google Scholar]

- Besser, A.; Shackelford, T.K. Mediation of the effects of the big five personality dimensions on negative mood and confirmed affective expectations by perceived situational stress: A quasi-field study of vacationers. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Higgins, C.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Barrick, M.R. The Big Five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Pers. Psychol. 1999, 52, 621–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuenyane, Z.M. Career guidance needs assessment of black secondary school students in the transvaal province of the republic of South Africa. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 1983, 6, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H. Reduction in state anxiety scores of freshmen through a course in career decision. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2005, 5, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostendorf, F.; Angleitner, A. On the generality and comprehensiveness of the five factor model of personality: Evidence for five robust factors in questionnaire data. In Modern Personality Psychology: Critical Reviews and New Directions; Caprara, G.V., van Heck, G.L., Eds.; Harvester Wheatsheaf: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 73–109. [Google Scholar]

- Baranik, L.E.; Barron, K.E.; Finney, S.J. Measuring goal orientation in a work domain: Construct validity evidence for the 2 × 2 framework. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2007, 67, 697–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, C.; Archer, J. Achievement Goals in the Classroom: Students’ Learning Strategies and Motivation Processes. J. Educ. Psychol. 1988, 80, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO FiveFactor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, TX, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martinez, V.; John, O.P. Los Cinco Grandes Across cultures and ethnic groups: Multitrait-multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 729–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spörrle, M.; Bekk, M. Meta-analytic guidelines for evaluating single-item reliabilities of personality instruments. Assessment 2014, 21, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, S.A.; Hampson, S.E. Measuring the Big Five with single items using a bipolar response scale. Eur. J. Personal. 2005, 19, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; John, O.P. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurven, M.; von Rueden, C.; Massenkoff, M.; Kaplan, H.; Lero Vie, M. How universal is the Big Five? Testing the five-factor model of personality variation among forager-farmers in the Bolivian Amazon. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fleeson, W. Toward a structure- and process-integrated view of personality: Traits as density distributions of states. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 1011–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Day, E.A.; Radosevich, D.J.; Chasteen, C.S. Construct- and criterion-related validity of four commonly used goal orientation instruments. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 28, 434–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao-Lin, N.; Duda, J. Construct validity of multiple achievement goals: A multitrait-multimethod approach. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 7, 503–520. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K. The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 1991, 44, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, R.; Hogan, J.; Roberts, B.W. Personality measurement and employment decisions: Questions and answers. Am. Psychol. 1996, 51, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymark, P.H.; Schmit, M.J.; Guion, R.M. Identifying potentially useful personality constructs for employee selection. Pers. Psychol. 1997, 50, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Judge, T.A. Core self-evaluations: A review of the trait and its role in job satisfaction and job performance. Eur. J. Personal. 2003, 17, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bipp, T.; Steinmayr, R.; Spinath, B. Personality and achievement motivation: Relationship among Big Five domain and facet scales, achievement goals, and intelligence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008, 44, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorić, I.; Penezić, Z.; Burić, I. The Big Five personality traits, goal orientations, and academic achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2017, 54, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, K.W.; Sheikh, E.; Carter, H.; Lamm, A.J. Predicting Undergraduate Leadership Student Goal Orientation Using Personality Traits. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2017, 16, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspi-Baruch, O. Big Five Personality and Creativity: The Moderating Effect of Motivational Goal Orientation. J. Creat. Behav. 2019, 53, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Motivational processes affecting learning. Am. Psychol. 1986, 41, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessing, G.E. Letters and Works, Volumes 8 and 9; Deutscher Klassiker Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2003; Available online: https://wist.info/lessing-gotthold/28570/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).