An Empirical Test of Mobile Service Provider Promotions on Repurchase Intentions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Determinants of Mobile Repurchase Intentions

2.2. Brand Attitudes

2.3. Functional Quality and Design Quality

2.4. Online Reviews

3. The Role of M-Promotions

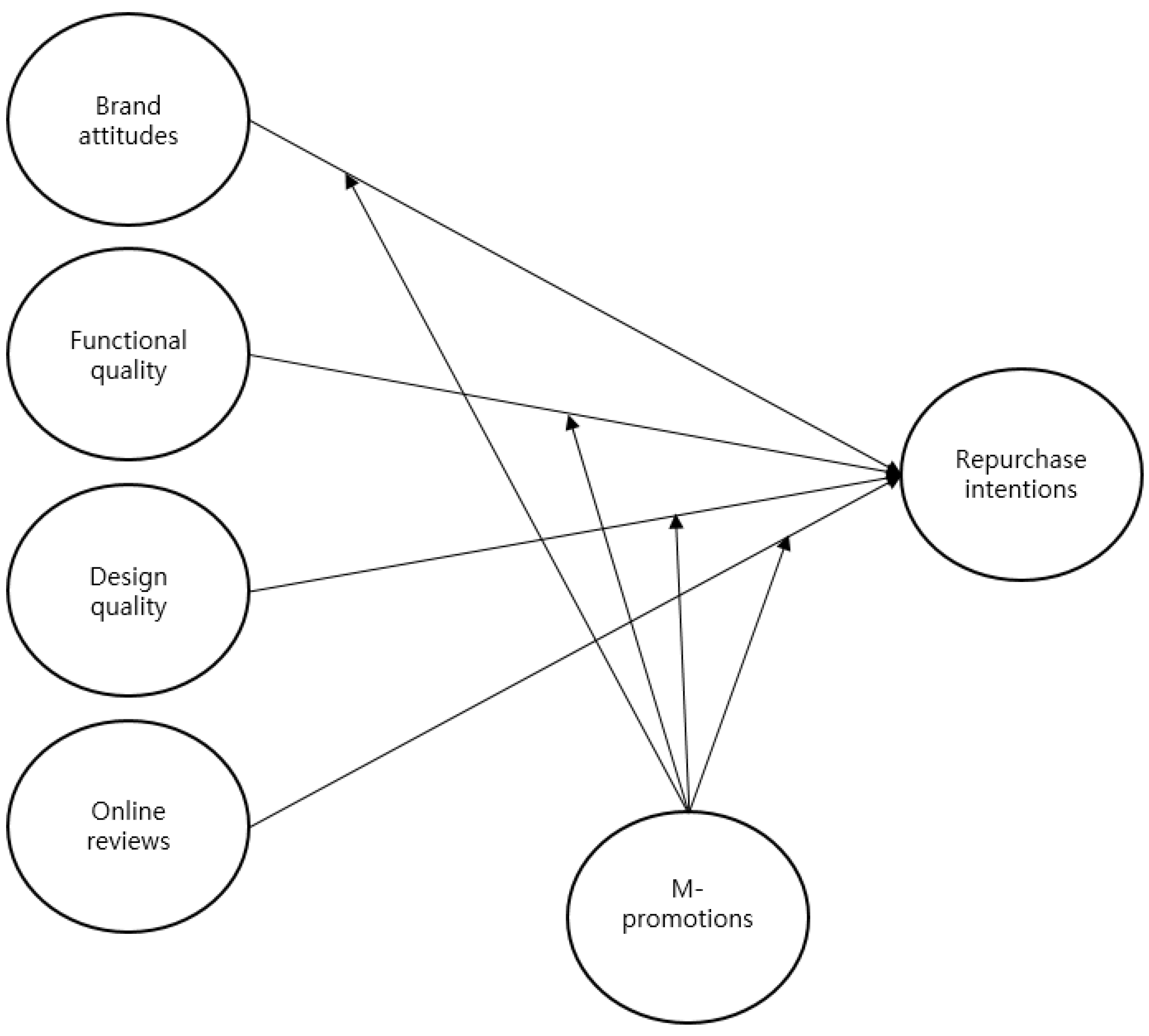

Hypotheses of the Moderating Role of M-Promotions

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample Data

4.2. Measures

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garnefeld, I.; Böhm, E.; Klimke, L.; Oestreich, A. I Thought It was Over, but Now It is Back: Customer Reactions to ex post Time Extensions of Sales Promotions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Natter, M.; Spann, M. Sampling. Discounts or Pay-What-You-Want: Two Filed Experiments. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2014, 31, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, I.; Carmon, Z.; O’Curry, S. Experimental Evidence on the Negative Effect of Product Features and Sales Promotions on Brand Choice. Mark. Sci. 1994, 13, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonlertvanich, K. Relationship between Sales Promotions, Duration of Receiving Reward and Customer Preference: A Case Study on Financial Product. J. Acad. Bus. Econ. 2010, 10, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ailawadi, K.L.; Harlam, B.; César, J.; Trounce, D. Promotion Profitability for a Retailer: The Role of Promotion, Brand, Category, and Store Characteristics. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Chi, C.; Chen, J. A New Perspective on the Effects of Price Promotions in Taiwan: A Longitudinal Study of a Chinese Society. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.P. The Double Jeopardy of Sales Promotions. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Tang, L.; Fiore, A.M. Restaurant Brand Pages on Facebook: Do Active Member Participation and Monetary Sales Promotions Matter? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1662–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swait, J.; Erdem, T. The Effects of Temporal Consistency of Sales Promotions and Availability on Consumer Choice Behavior. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Yoo, J. The Long-term Effects of Sales Promotions on Brand Attitude across Monetary and Non-monetary Promotions. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelVecchio, D.; Henard, D.H.; Freling, T.H. The Effect of Sales Promotion on Post-Promotion Brand Preference: A Meta-analysis. J. Retail. 2006, 82, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garretson, J.A.; Fisher, D.; Burton, S. Antecedents of Private Label Attitude and National Brand Promotion Attitude: Similarities and Differences. J. Retail. 2002, 78, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Waechter, K.A.; Bai, X. Understanding Consumers’ Continuance Intention toward Mobile Purchase: A Theoretical Framework and Empirical Study: A Case of China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, K.; Chen, C. What Drives Smartwatch Purchase Intention? Perspectives from Hardware, Software, Design, and Value. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, M.T.; Noble, S.M.; Noble, C.H. The Influence of C2C Communications in Online Brand Communities on Customer Purchase Behavior. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 634–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motyka, S.; Grewal, D.; Aguirre, E.; Mahr, D.; Ruyter, K.; Wetzels, M. The Emotional Review-reward Effect: How Do Reviews Increase Impulsivity? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 1032–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Gu, B.; Whinston, A.B. Do Online Reviews Matter? An Empirical Investigation of Panel Data. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 45, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, G.; Fudenberg, D. Word-of-Mouth Communication and Social Learning. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 93–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, B.E.; Louie, T.A. Effects of Retraction of Price Promotions on Brand Choice Behavior for Variety-seeking and Last-purchase-loyal Customers. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 27, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Lee, T.M. Antecedents of Online Reviews’ Usage and Purchase Influence: An Empirical Comparisons of U.S. and Korean Consumers. J. Interact. Mark. 2009, 23, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.; Goehring, J.; Hui, S.; Pancras, J.; Thornswood, L. Mobile Promotions: A Framework and Research Priorities. J. Interact. Mark. 2016, 34, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dolbec, P.; Chebat, J. The Impact of a Flagship vs. a Brand Store on Brand Attitude, Brand Attachment and Brand Equity. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzellis, L. Mobile Phone Choice: Technology versus Marketing: The Brand Effect in the Italian Market. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 610–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.; Chang, J.; Tang, K. Exploring the Influential Factors in Continuance Usage of Mobile Social Apps: Satisfaction, Habit, and Customer Value Perspectives. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, M.; Lu, T.; Bailly, G.; Oulasvirta, A.; Majidi, C.; Steimie, J. iSkin: Flexible, Stretchable and Visually Customizable On-body Touch Sensors for Mobile Computing. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 2991–3000. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wen, C.; Wang, R. Design and Performance Attributes Driving Mobile Travel Application Engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, X. Impact of Online Consumer Reviews on Sales: The Moderating Role of Product and Consumer Characteristics. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, T.; Benkenstein, M. When Good WOM Hurts and Bad WOM Gains: The Effect of Untrustworthy Online Reviews. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5993–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Bernoff, J. Groundswell; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, F.R.; Mendoza, N.A. Too Popular to Ignore: The Influence of Online Reviewers on Purchase Intentions of Search and Experience Products. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowatsch, T. The Role of Product Reviews on Mobile Devices for In-store Purchases: Consumers’ Usage Intentions, Costs and Store Preferences. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2011, 6, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Li, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, M. What in Consumer Reviews Affects the Sales of Mobile Apps: A Multifacet Sentiment Analysis Approach. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2015, 20, 236–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.K.; Inman, J.J.; Huang, Y.; Suher, J. The Effect of In-store Travel Distance on Unplanned Spending: Applications to Mobile Promotion Strategies. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Fu, S.; Qin, J. Determinants of Consumers’ Attitudes toward Mobile Advertising: The Mediating Roles of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S.; Uncles, M. Sales Promotion Effectiveness: The Impact of Consumer Differences at an Ethnic-group Level. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.H.; Chang, Y.; Yeh, C.; Liao, C. Promote the Price Promotion: The Effects of Price Promotions on Customer Evaluations in Coffee Chain Stores. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, S.; Yagüe, M.J. Tourist Loyalty to Tour Operator: Effects of Price Promotions and Tourist Effort. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarejo-Ramos, A.F.; Sánchez-Franco, M.J. The Impact of Marketing Communication and Price Promotion on Brand Equity. J. Brand Manag. 2005, 12, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K.E.; Garretson, J.A.; Kurtz, D.L. An Exploratory Study into the Purchase Decision Process used by Leisure Travelers in Hotel Selection. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 1995, 2, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Dac, N.N.; Carson, S.T.; Moore, W.L. The Effects of Positive and Negative Online Customer Reviews: Do Brand Strength and Category Maturity Matter? J. Mark. 2013, 77, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.Y.; Bradlow, E.T. Automated Marketing Research Using Online Customer Reviews. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, B.; Cartwright, D.K. The Impact of Online User Reviews on Cameras Sales. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 1115–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghubir, P.; Corfman, K. When Do Price Promotions Affect Pretrial Brand Attitudes? J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, L.T. User Experience Evaluation Methods for Mobile Device. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Innovation Computing Technology, London, UK, 29–31 August 2013; pp. 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, B. A Multidimensional and Hierarchical Model of Mobile Service Quality. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2009, 8, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; McLeay, F. E-WOM and Accommodation: An Analysis of the Factors that Influence Travelers’ Adoption of Information from Online Reviews. J. Travel Res. 2013, 53, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honea, H.; Dahl, D.W. The Promotion Affect Scale: Defining the Affective Dimensions of Promotion. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaman, L. Gender Differences in Hong Kong Adolescent Consumers’ Green Purchasing Behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for Integrating Moderation and Mediation: A General Analytical Framework Using Moderated Path Analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; West, S.G.; Sheets, V. A Comparison of Methods to Test Mediation and Other Intervening Variable Effects. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugtvedt, C.P.; Petty, R.E. Personality and Persuasion: Need for Cognition Moderates the Persistence and Resistance of Attitudes Changes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M. An Exploratory Study on Attitude Persistence Using Sales Promotion. J. Manag. Issues 2008, 20, 401–416. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Filieri, R. What Makes Online Reviews Helpful? A Diagnosticity-Adoption Framework to Explain Informational and Normative Influences in e-WOM. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Korfiatis, N. Trying before Buying: The Moderating Role of Online Reviews in Trial Attitude Formation toward Mobile Applications. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2015, 19, 77–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.; Leem, B. Analysis to Customer Churn Provoker’s Roles Using Call Network of a Telecom Company. Korean J. Appl. Stat. 2013, 26, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyles, S.; Gokey, T.C. Customer Retention is not enough: Defecting Customers are far less of a Problem than Customers Who Change Their Buying Patterns. Mckinsey Q. 2002, 1, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Waldeck, Y. Market Share of Mobile Phone Service Providers in South Korea 2019. Statista 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/700467/south-korea-mobile-phone-market-share/ (accessed on 16 December 2020).

| Constructs | Mean (SD) | Factor | AVE χ2(d.f.) and |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loading | Indexes | ||

| Brand attitude | 3.67 (0.94) | 0.59 | 309.556 (137) |

| Dislike/Like | 0.74 | CFI = 0.953 | |

| Harmful/Beneficial | 0.74 | TLI = 0.941 | |

| Unfavorable/Favorable | 0.83 | RMSEA = 0.052 | |

| Inappropriate/Appropriate | 0.77 | ||

| Functional quality | 2.94 (1.20) | 0.56 | |

| It is easy to make a call. | 0.72 | ||

| This mobile device has simple steps to take a picture. | 0.77 | ||

| This device makes it easy to find what I need. | 0.72 | ||

| It operates without any special hardware. | 0.78 | ||

| Design quality | 3.82 (.99) | 0.69 | |

| When I choose a mobile device, color is important to me. | 0.78 | ||

| The slim shape of a mobile device gives me a deep impression. | 0.87 | ||

| In general, this mobile design meets my needs. | 0.83 | ||

| Online reviews | 2.68 (1.03) | 0.61 | |

| The overall ranking of different mobile devices facilitates the | 0.74 | ||

| evaluation of the available alternatives. | |||

| Overall mobile device rankings help me to rapidly select the | 0.82 | ||

| best device among several alternatives. | |||

| The overall online reviews are trustworthy. | 0.78 | ||

| Mobile service provider promotions | 2.72 (1.08) | 0.68 | |

| Unlucky/lucky | 0.78 | ||

| Valueless/valuable | 0.77 | ||

| Discouraged/encouraged | 0.87 | ||

| Inconsistent/consistent | 0.87 | ||

| Repurchase intention | 2.91 (1.27) | 0.61 | |

| I will rebuy the same mobile device in the near future. | 0.73 | ||

| I plan to rebuy the same mobile device on a regular basis. | 0.89 | ||

| I will rebuy the same mobile device for my convenience | 0.71 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Brand attitude | 0.59 | |||||

| 2. Functional quality | 0.34 | 0.56 | ||||

| 3. Design quality | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.69 | |||

| 4. Online reviews | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.61 | ||

| 5. M-promotions | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.68 | |

| 6. Repurchase intention | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.54 |

| H1 | Std. Beta | t-value | LLCI | ULCI |

| Brand attitude (BA) | 0.51 * | 1.97 | 0.0021 | 1.0207 |

| M-promotions (MP) | 0.19 (ns) | 0.34 | −0.9185 | 1.3049 |

| BA * MP | −0.01 (ns) | −0.04 | −0.3144 | 0.3033 |

| Model: R2 = 0.17; F = 14.60 (df1 = 3, df2 = 210, p = 0.000) | ||||

| H2 | Std. Beta | t-value | LLCI | ULCI |

| Functional quality (FQ) | 0.36 * | 2.12 | 0.0277 | 0.7051 |

| M-promotions (MP) | −0.88 ** | −2.99 | −0.3003 | −1.4609 |

| FQ * MP | −0.19* | −1.89 | −0.3831 | 0.0240 |

| Model: R2 = 0.08; F = 6.07 (df1 = 3.0, df2 = 210, p = 0.000) | ||||

| H3 | Std. Beta | t-value | LLCI | ULCI |

| Design quality (DQ) | 0.42 (ns) | 1.57 | -0.1087 | 0.9643 |

| M-promotions (MP) | 0.12 (ns) | 0.19 | −1.1922 | 1.4507 |

| DQ * MP | 0.01 (ns) | 0.03 | −0.3256 | 0.3345 |

| Model: R2 = 0.12; F = 9.60 (df1 = 3.0, df2 = 210, p = 0.000) | ||||

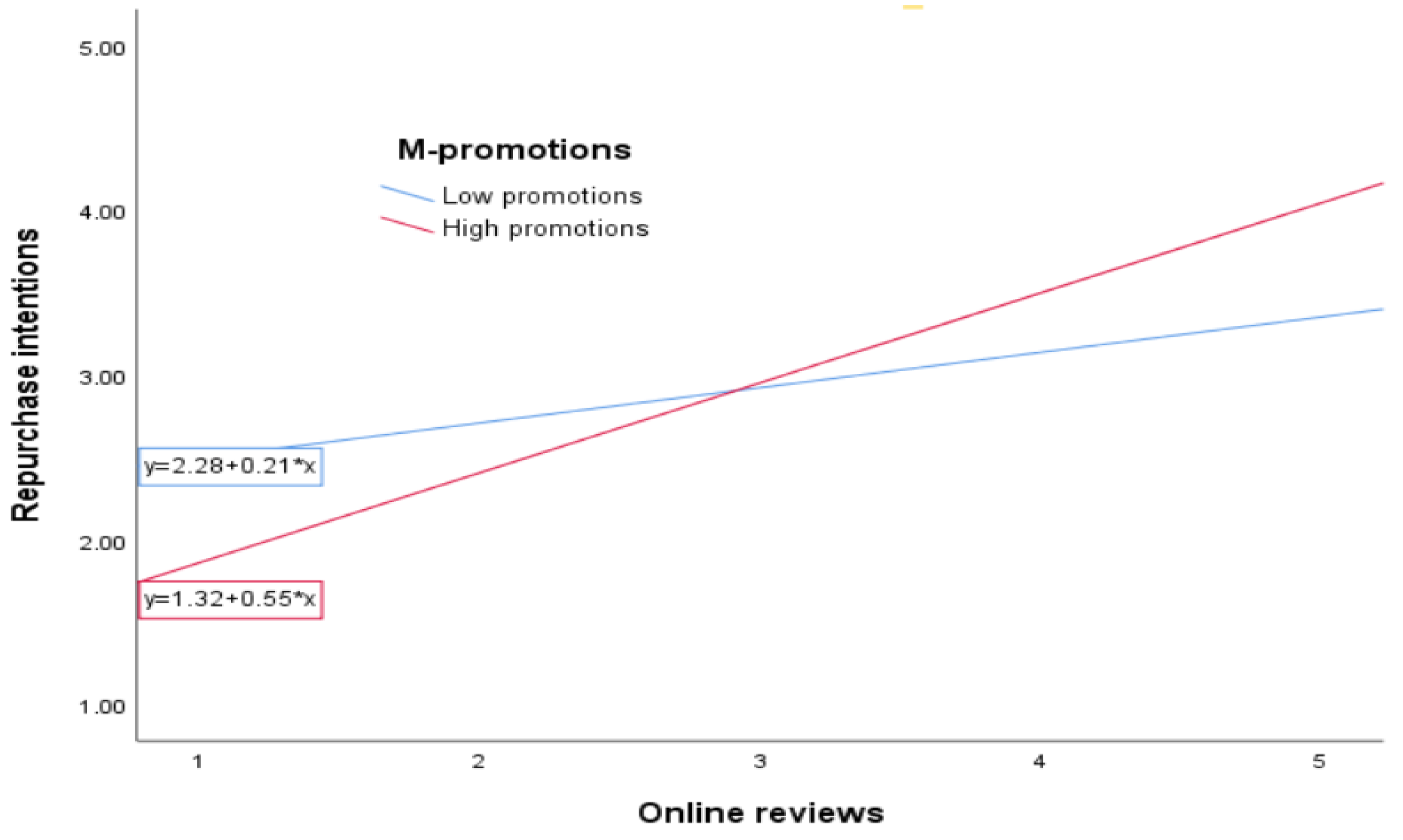

| H4 | Std. Beta | t-value | LLCI | ULCI |

| Online reviews (OR) | 0.11 (ns) | 0.56 | 0.0028 | 0.4225 |

| M-promotions (MP) | 0.96 ** | 2.38 | 0.1689 | 1.7625 |

| OR * MP | 0.33 ** | 2.46 | −0.0663 | 0.5969 |

| Model: R2 = 0.15; F = 12.35 (df1 = 3.0, df2 = 210, p = 0.000) | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, K.; Ha, H.-Y. An Empirical Test of Mobile Service Provider Promotions on Repurchase Intentions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052894

Ji K, Ha H-Y. An Empirical Test of Mobile Service Provider Promotions on Repurchase Intentions. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052894

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Kwangchul, and Hong-Youl Ha. 2021. "An Empirical Test of Mobile Service Provider Promotions on Repurchase Intentions" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052894

APA StyleJi, K., & Ha, H.-Y. (2021). An Empirical Test of Mobile Service Provider Promotions on Repurchase Intentions. Sustainability, 13(5), 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052894