Influencers in the Political Conversation on Twitter: Identifying Digital Authority with Big Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Changes in the Way of Influencing Social Media

2.2. Influence and Digital Authority

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Gaps and Objectives

- O1.

- Identify those users who achieve a greater capacity for social influence on Twitter during the political conversation related to a relevant event.

- O2.

- Determine which types of actors have the greatest numerical presence within the influencers in the political discussion on Twitter.

- O3.

- Discover which groups of actors within the influencers obtain the greatest digital authority to have an effect and gain prominence in the public debate on Twitter.

3.2. Data Collection and Processing

3.3. Network Analysis Procedures

4. Results: Identification of the Main Influencers in the Political Conversation on Twitter Based on Their Digital Authority

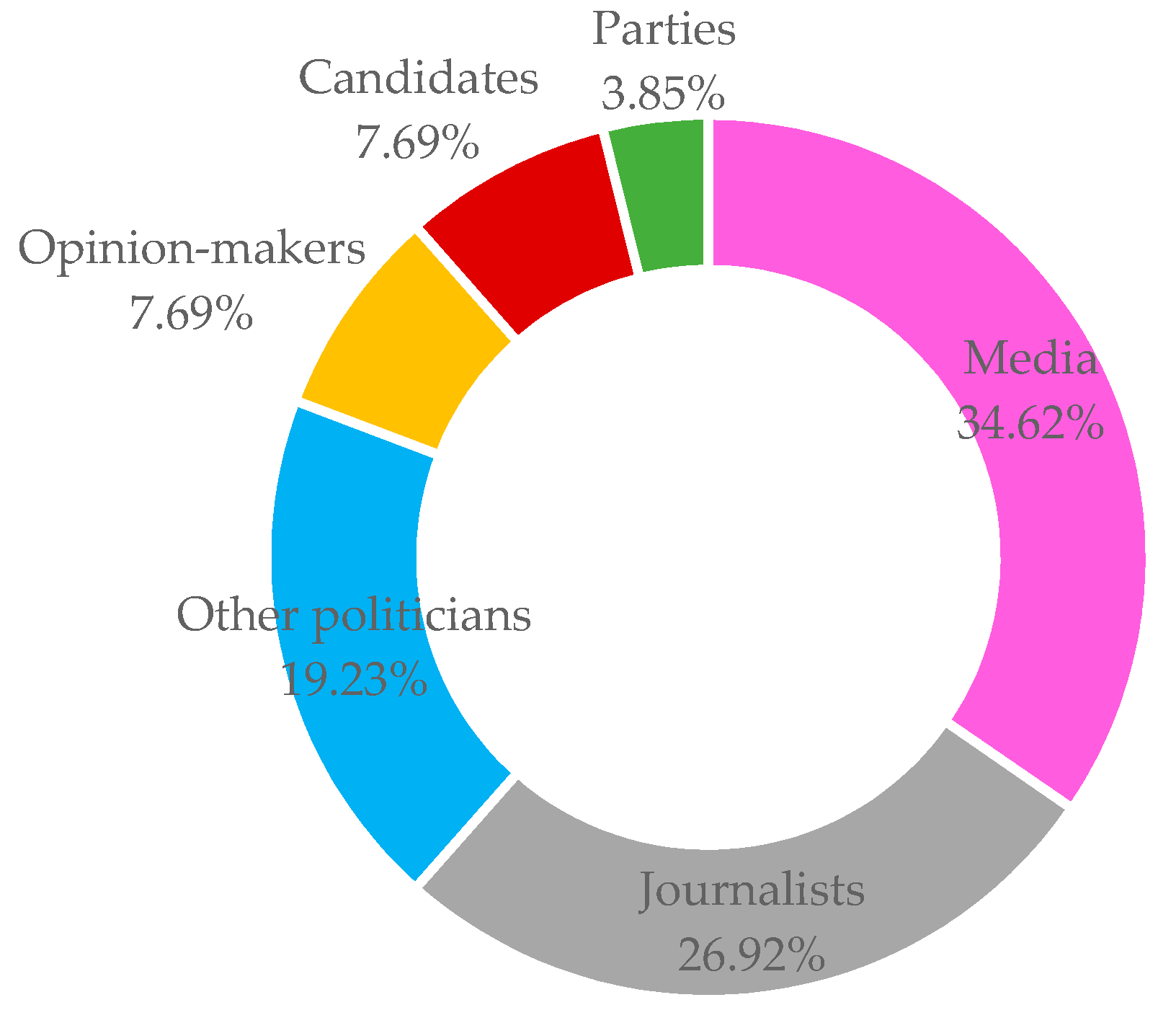

4.1. Numerical Presence of Influencers in the Political Conversation on Twitter

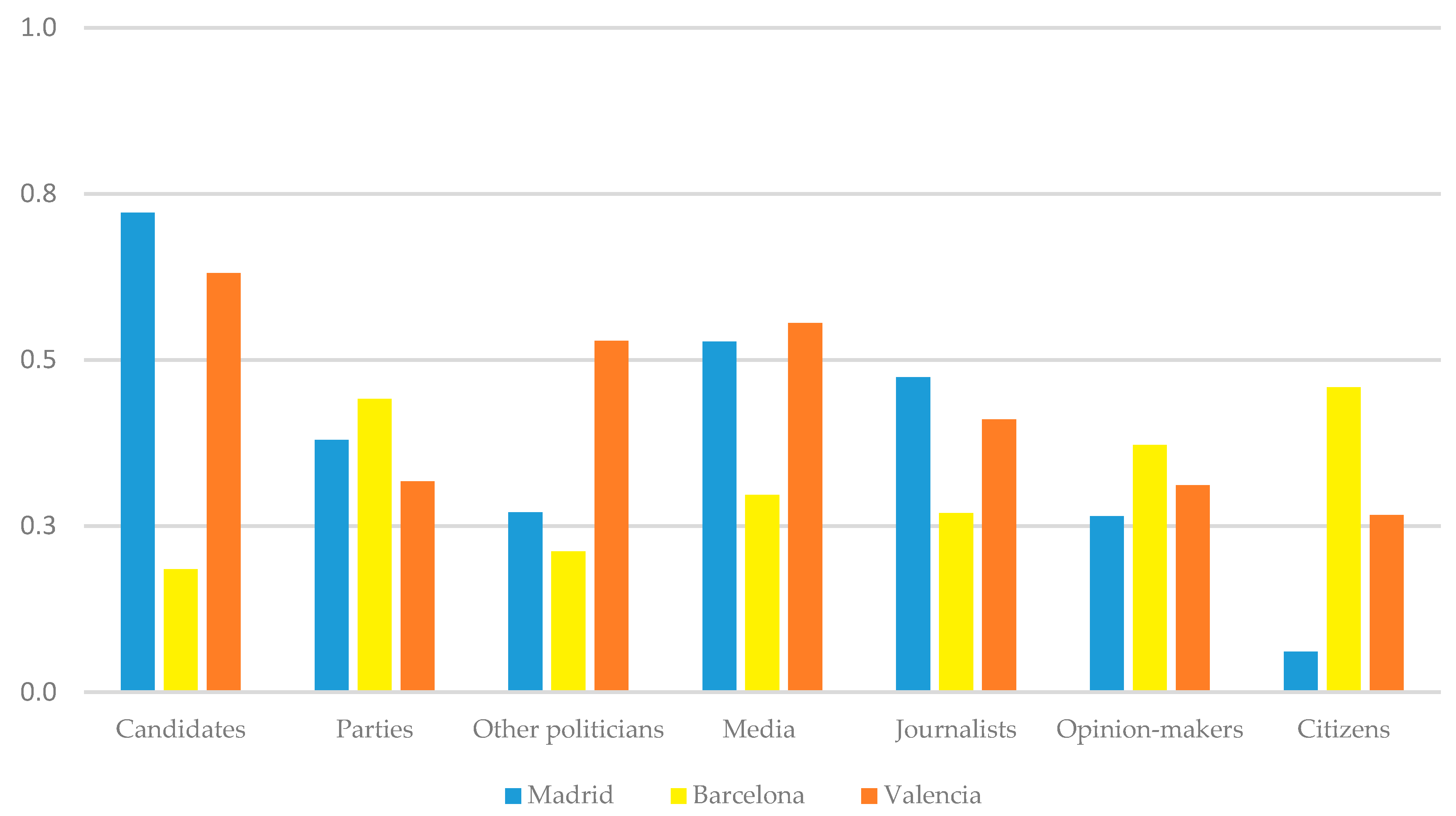

4.2. Level of the Digital Authority of Influencers in the Political Conversation on Twitter per Type and Network

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Dijck, J. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, A. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Casero-Ripollés, A.; Feenstra, R.A.; Tormey, S. Old and new media logics in an electoral campaign: The case of Podemos and the two-way street mediatization of politics. Int. J. Press Politics 2016, 21, 378–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Curiel, C.; Limón-Naharro, P. Political influencers. A study of Donald Trump’s personal brand on Twitter and its impact on the media and users. Commun. Soc. 2019, 32, 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Curiel, C.; García-Gordillo, M. Indicadores de influencia de los políticos españoles en Twitter. Un análisis en el marco de las elecciones en Cataluña. Estud. Sobre Mensaje Periodístico 2020, 26, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Gass, R.H. Social Influence, Sociology of. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; James, E., Wright, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 348–354. [Google Scholar]

- Pratkanis, A.R. The Science of Social Influence: Advances and Future Progress; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B. Influence: Science and Practice, 5th ed.; Pearson/Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, M.; Haddadi, H.; Benevenuto, F.; Gummadi, K.P. Measuring user influence in Twitter: The million follower fallacy. In Proceedings of the Fourth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Washington, DC, USA, 23–26 May 2010; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, P.; Berelson, B.; Gaudet, H. The People’s Choice: How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Anspach, N.M. The new personal influence: How our Facebook friends influence the news we read. Political Commun. 2017, 34, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Iranzo, P.; Gallardo-Echenique, E. Studygrammers: Learning Influencers. Comun. Media Educ. Res. J. 2020, 28, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel-Turim, V.; Micó-Sanz, J.L.; Ordeix-Rigo, E. Who Did the Top Media from Spain Started Following on Twitter? An Exploratory Data Analysis Case Study. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, A. Influence of media on the political conversation on Twitter: Activity, popularity, and authority in the digital debate in Spain. Icono 2020, 14, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Carrión, E.L.; Aguaded, I. The most influencer instagramers from Ecuador. Univ. Rev. De Cienc. Soc. Y Hum. 2019, 31, 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaino-Verdú, A.; de Casas Moreno, P.; Aguaded, I. Youtubers e instagrammers: Una revisión sistemática cuantitativa. In Competencia Mediática y Digital: Del Acceso al Empoderamiento; Grupo Comunicar: Paraná, Argentina, 2019; pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.W.; Sang, Y.; Blasiola, S.; Park, H.W. Predicting opinion leaders in Twitter activism networks: The case of the Wisconsin recall election. Am. Behav. Sci. 2014, 58, 1278–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M.; Usher, N. Framing in a fractured democracy: Impacts of digital technology on ideology, power and cascading network activation. J. Commun. 2018, 68, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Meri, A.; Casero-Ripollés, A. El debate de la actualidad periodística española en Twitter: Del corporativismo de periodistas y políticos al activismo ciudadano. Observatorio 2016, 10, 56–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micó, J.L.; Casero-Ripollés, A. Political activism online: Organization and media relations in the case of 15M in Spain. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2014, 17, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W.L.; Segerberg, A.; Yang, Y. The strength of peripheral networks: Negotiating attention and meaning in complex media ecologies. J. Commun. 2018, 68, 659–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewksbury, D.; Rittenberg, J. News on the Internet: Information and Citizenship in the 21st Century; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Political communication in media society: Does democracy still enjoy an epistemic dimension? The impact of normative theory on empirical research. Commun. Theory 2006, 16, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, A. Research on political information and social media: Key points and challenges for the future. Prof. Inf. 2018, 27, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, R.A.; Tormey, S.; Casero-Ripollés, A.; Keane, J. Refiguring Democracy: The Spanish Political Laboratory; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dagoula, C. Mapping political discussions on Twitter: Where the elites remain elites. Media Commun. 2019, 7, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, E.; Gaffney, D. The multiple facets of influence: Identifying political influentials and opinion leaders on Twitter. Am. Behav. Sci. 2014, 58, 1260–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C. Social Media: A Critical Introduction; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kolli, S.; Khajeheian, D. How Actors of Social Networks Affect Differently on the Others? Addressing the Critique of Equal Importance on Actor-Network Theory by Use of Social Network Analysis. In Contemporary Applications of Actor Network Theory; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2020; pp. 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Solé, F. Interactive behavior in political discussions on Twitter: Politicians, media, and citizens’ patterns of interaction in the 2015 and 2016 electoral campaigns in Spain. Soc. Media Soc. 2018, 4, 2056305118808776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberá, P.; Casas, A.; Nagler, J.; Egan, P.J.; Bonneau, R.; Jost, J.T.; Tucker, J.A. Who leads? Who follows? Measuring issue attention and agenda setting by legislators and the mass public using social media data. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2019, 113, 883–901. [Google Scholar]

- Baviera, T. Influence in the political Twitter sphere: Authority and retransmission in the 2015 and 2016 Spanish General Elections. Eur. J. Commun. 2018, 33, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, M.; Vásquez, J.; Halpern, D.; Valenzuela, S.; Arriagada, E. One step, two step, network step? Complementary perspectives on communication flows in Twittered citizen protests. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2017, 35, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ugarte, D. Participación, adhesión e invisibilidad. La venganza de Habermas. Telos Cuad. Comun. Innovación 2014, 98, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Baeza-Yates, R.; Saez-Trumper, D. Wisdom of the Crowd or Wisdom of a Few? An Analysis of Users’ Content Generation. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM Conference on Hypertext & Social Media; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barabási, A.L. Network Science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme, F.; González-Cantergiani, P. Measuring user influence on Twitter: A survey. Inf. Process. Manag. 2016, 52, 949–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacich, P. Some unique properties of eigenvector centrality. Soc. Netw. 2007, 29, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhnau, B. Eigenvector-centrality—a node-centrality? Soc. Netw. 2000, 22, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Zuo, L. Dialoguing with Data and Data Reduction: An Observational, Narrowing-Down Approach to Social Media Network Analysis. Journal. Media 2021, 2, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Fresno García, M.; Daly, A.J.; Sánchez-Cabezudo, S.S. Identifying the new influencers in the Internet Era: Social media and social network analysis. Reis Rev. Española Investig. Sociológicas 2016, 153, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, T.; Jackson, D.; Broersma, M. New platform, old habits? Candidates’ use of Twitter during the 2010 British and Dutch general election campaigns. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.G.; Molyneux, L.; Coddington, M.; Holton, A. Tweeting Conventions: Political journalists’ use of Twitter to cover the 2012 presidential campaign. Journal. Stud. 2014, 15, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, R.D.; Dominick, J.R. Mass Media Research: An Introduction, 10th ed.; Wadsworth: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Page, L.; Brin, S.; Motwani, R.; Winograd, T. The Page Rank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web; Stanford InfoLab: Stanford, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Curiel, C.; Jiménez-Marín, G.; García-Medina, I. Influence of the agenda and framing study in the electoral framework of the Procés of Catalonia. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2020, 75, 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Micó, J.L.; Carbonell, J.M. The Catalan Political Process for Independence: An Example of the Partisan Media System. Am. Behav. Sci. 2017, 61, 428–440. [Google Scholar]

- Gruzd, A.; Wellman, B. Networked Influence in Social Media: Introduction to the Special Issue. Am. Behav. Sci. 2014, 58, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, A.; Micó-Sanz, J.L.; Díez-Bosch, M. Digital public sphere and geography: The influence of physical location on Twitter’s political conversation. Media Commun. 2020, 8, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Actor | Typology | Eigencentrality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ignacio Escolar | Journalist | 0.786997083 |

| 2 | PSOE | Political party | 0.706532164 |

| 3 | Europa Press | Media | 0.651858492 |

| 4 | Jordi Evole | Journalist | 0.644632466 |

| 5 | Ana Pastor | Journalist | 0.628756421 |

| 6 | Público | Media | 0.622736169 |

| 7 | El País | Media | 0.621643508 |

| 8 | Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba | Other politicians (PSOE) | 0.60958261 |

| 9 | eldiario.es | Media | 0.601095483 |

| 10 | Julia Otero | Journalist | 0.600774466 |

| 11 | Cadena SER | Media | 0.592934826 |

| 12 | Pedro Sánchez | Candidate (PSOE) | 0.592028256 |

| 13 | Àngels Barceló | Journalist | 0.556088755 |

| 14 | Huff Post | Media | 0.552359586 |

| 15 | Pablo Iglesias | Candidate (Podemos) | 0.552238101 |

| 16 | Jesús Maraña | Journalist | 0.546624497 |

| 17 | Carme Chacón | Other politicians (PSOE) | 0.543506924 |

| 18 | Miquel Iceta | Other politicians (PSOE) | 0.536300656 |

| 19 | Vilaweb | Media | 0.53239295 |

| 20 | Fernando Garea | Journalist | 0.530605927 |

| 21 | Antoni Gutiérrez Rubi | Opinion-maker | 0.529979083 |

| 22 | Agencia EFE | Media | 0.527059663 |

| 23 | Gaspar Llamazares | Other politicians (IU) | 0.527027224 |

| 24 | Ada Colau | Other politicians (Podemos) | 0.50394449 |

| 25 | 20M | Media | 0.502605298 |

| 26 | Sonia Sánchez | Opinion-maker | 0.500221398 |

| Typology | Madrid | Barcelona | Valencia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidates | 0.72137661 | 0.18464595 | 0.63058508 |

| Parties | 0.37948120 | 0.44118190 | 0.31722629 |

| Other politicians | 0.27037496 | 0.21172166 | 0.52851631 |

| Media | 0.52749878 | 0.29665883 | 0.55554125 |

| Journalists | 0.47411694 | 0.26946980 | 0.41068487 |

| Opinion-makers | 0.26485281 | 0.37183448 | 0.31129425 |

| Citizens | 0.06096887 | 0.45851371 | 0.26625259 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casero-Ripollés, A. Influencers in the Political Conversation on Twitter: Identifying Digital Authority with Big Data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052851

Casero-Ripollés A. Influencers in the Political Conversation on Twitter: Identifying Digital Authority with Big Data. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052851

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasero-Ripollés, Andreu. 2021. "Influencers in the Political Conversation on Twitter: Identifying Digital Authority with Big Data" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052851

APA StyleCasero-Ripollés, A. (2021). Influencers in the Political Conversation on Twitter: Identifying Digital Authority with Big Data. Sustainability, 13(5), 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052851