The Role of Regulatory Focus and Emotion Recognition Bias in Cross-Cultural Negotiation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- Cultural differences in chronic regulatory focus will lead to cultural biases in emotion recognition, because people are inclined to behave in ways that increase regulatory fit.

- (ii)

- Assuming that there are cultural biases in emotion recognition, in emotionally ambiguous situations, people from different cultures will reach different conclusions about the opponent’s emotion. This is because they recognize the same ambiguous emotional expression differently.

- (iii)

- These conclusions about the opponent’s emotion will be used as social information in negotiations and thus, people may show distinctive negotiation behaviors.

2. Cross-Cultural Negotiation

2.1. Cross-Cultural Negotiation: Focus on Cognition and Behavior

2.2. Limitations of Research on Cross-Cultural Negotiation

3. Regulatory Focus and Emotion Recognition

3.1. Cultural Differences in Regulatory Focus

3.2. Regulatory Fit and Cognitive Biases

3.3. Regulatory Fit and Emotion Recognition Biases

3.3.1. Cultural Difference in Emotion Recognition

3.3.2. An Alternative Explanation for the Cultural Difference in Emotion Recognition

4. Emotion Recognition and Behavior in Cross-Cultural Negotiation

4.1. Focus on Emotional Experience of Negotiators (Intra-Personal Effect of Emotion)

4.2. Focus on Emotion as Social Information (Inter-Personal Effect of Emotion)

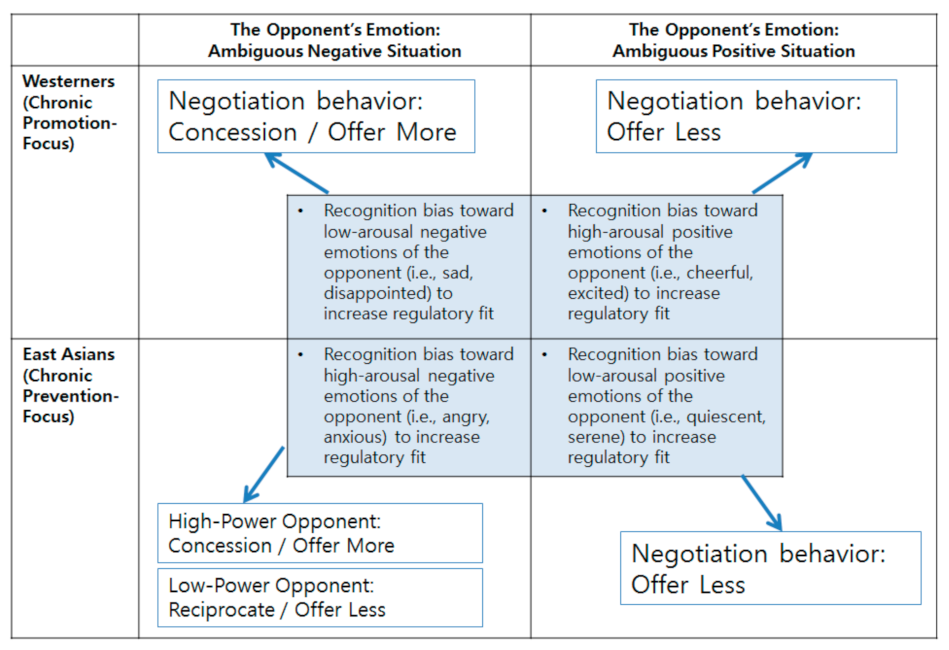

5. Motivation–Emotion Model of Cross-Cultural Negotiation

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rubin, J.Z.; Brown, B.R. The Social Psychology of Bargaining and Negotiation; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L. Negotiation behavior and outcomes: Empirical evidence and theoretical issues. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, R.J.; Weiss, S.E.; Lewin, D. Models of conflict, negotiation and third party intervention: A review and synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 209–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, R.J.; Litterer, J.A. Negotiation; Richard, D., Ed.; Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Nishii, L.H.; Holcombe, K.M.; Dyer, N.; Ohbuchi, K.I.; Fukuno, M. Cultural influences on cognitive representations of conflict: Interpretations of conflict episodes in the United States and Japan. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Christakopoulou, S. Culture and negotiator cognition: Judgment accuracy and negotiation processes in individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1999, 79, 248–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.L.; Gelfand, M.J.; Hong, Y.-Y.; Chiu, C.-Y. Culture, work, and the self: The mutual influence of social and industrial organizational psychology. In SIOP Organizational Frontiers Series: The Self at Work: Fundamental Theory and Research; Ferris, D.L., Johnson, R.E., Sedikides, C., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 225–251. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Higgins, M.; Nishii, L.H.; Raver, J.L.; Dominguez, A.; Murakami, F.; Yamaguchi, S.; Toyama, M. Culture and egocentric perceptions of fairness in conflict and negotiation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade-Benzoni, K.A.; Okumura, T.; Brett, J.M.; Moore, D.A.; Tenbrunsel, A.E.; Bazerman, M.H. Cognitions and behavior in asymmetric social dilemmas: A comparison of two cultures. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, F.G.; Isen, A.M.; Turken, U. A neuropsychological theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J.P. Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Bless, H.; Bohner, G. Mood and persuasion: Affective states influence the processing of persuasive communications. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 24, 161–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyer, R.S.; Clore, G.L.; Isbell, L.M. Affect and information processing. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 31, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, G.J.; Van Dijk, E.; Van Beest, I.; Van Kleef, G.A. Why anger and disappointment affect other’s bargaining behavior differently: The moderating role of power and the mediating role of reciprocal and complementary emotions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kleef, G.A. How emotions regulate social life the emotions as social information (EASI) model. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, G.A.; De Dreu, C.K.W.; Manstead, A.S.R. An interpersonal approach to emotion in social decision making: The emotions as social information model. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 42, 45–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, G.A.; Côté, S. Emotional dynamics in conflict and negotiation: Individual, dyadic, and group processes. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 437–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesario, J.; Higgins, E.T. Making message recipients "feel right": How nonverbal cues can increase persuasion. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, L.A.; Hesse, S.J.; Petkova, Z.; Trudeau, L. “This story is right on”: The impact of regulatory fit on narrative engagement and persuasion. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Value from regulatory fit. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 14, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Pinelli, F. Regulatory focus and fit effects in organizations. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2020, 7, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feshbach, S.; Singer, R.D.; Feshbach, N. Effects of anger arousal and similarity upon the attribution of hostility to pictorial stimuli. J. Consult. Psychol. 1963, 27, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maner, J.K.; Kenrick, D.T.; Becker, D.V.; Robertson, T.E.; Hofer, B.; Neuberg, S.L.; Delton, A.W.; Butner, J.; Schaller, M. Functional projection: How fundamental social motives can bias interpersonal perception. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, M.J.; Baumeister, R.F. Motivated gratitude and the need to belong: Social exclusion increases gratitude for people low in trait entitlement. Motiv. Emot. 2019, 43, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, M.A.; Northcraft, G.B. Behavioral negotiation theory: A framework for conceptualizing dyadic bargaining. Res. Organ. Behav. 1991, 13, 147–190. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, J.G. A theory of the bargaining process. Am. Econ. Rev. 1965, 55, 6–94. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1816177 (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Nash, J.F., Jr. The bargaining problem. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1950, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J. Two-person cooperative games. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1953, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H. A classroom study of the dilemmas in interpersonal negotiations. In Strategic Interaction and Conflict; Archibald, K., Ed.; University of California, Institute of International Studies: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1966; pp. 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt, D.G.; Rubin, J.Z. Social Conflict: Escalation, Stalemate, and Settlement; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bazerman, M.H.; Carroll, J.S. Negotiator cognition. Res. Organ. Behav. 1987, 9, 247–288. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, M.A.; Bazerman, M.H. Negotiator cognition and rationality: A behavioral decision theory perspective. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1992, 51, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkley, R.L. Dimensions of conflict frame: Disputants’ interpretations of conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Dyer, N. A cultural perspective on negotiation: Progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2000, 49, 62–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.W.; Gelfand, M.J. Cultural differences and cognitive dynamics: Expanding the cognitive perspective on negotiation. In Handbook of Negotiation and Culture; Gelfand, M.J., Brett, J.M., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, A.; Srivastava, J.; Lee, S. The role of cultural orientation in bargaining under incomplete information: Differences in causal attributions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 2005, 96, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, M. Towards a model of cross-cultural I/O psychology. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (Vol. 4); Dunnette, M.D., Hough, L., Triandis, H., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 569–607. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.B.; Bond, M.H. Social Psychology: Across Cultures; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Erez, M.; Aycan, Z. Cross-cultural organizational behavior. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 479–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism and Collectivism; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Buchan, N.R.; Croson, R.T.A.; Johnson, E.J. When do fair beliefs influence bargaining behavior? Experimental bargaining in Japan and the United States. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.A.; Friedman, R.A.; Chi, S.C. ‘Ren Qing’versus the ‘Big Five’: The role of culturally sensitive measures of individual difference in distributive negotiations. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2005, 1, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartel, C.; Ashkanasy, N.M.; Zerbe, W. Emotions in Organizational Behavior; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley, C.H.; Pillutla, M.M. Negotiating in the United States and Hong Kong. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; De Cremer, D.; Wang, C. How ethically would Americans and Chinese negotiate? The effect of intra-cultural versus inter-cultural negotiations. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.T. How cultures collide. Psychol. Today 1976, 10, 66–97. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. Verbal communication styles and culture. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, W.L.; Brett, J.M. The negotiation dance: Time, culture, and behavioral sequences in negotiation. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yama, H.; Zakaria, N. Explanations for cultural differences in thinking: Easterners’ dialectical thinking and Westerners’ linear thinking. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2019, 31, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerman, M.H.; Curhan, J.R.; Moore, D.A.; Valley, K.L. Negotiation. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2000, 51, 279–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.J.; Aycan, Z. Cross-cultural interaction: What we know and what we need to know. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Jones, G.R.; Gonzalez, J.A. The role of affect in cross-cultural negotiations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 749–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. Culture and emotions in intercultural negotiations: An overview. In Handbook of Negotiation and Culture; Gelfand, M.J., Brett, J.M., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, H.; Shirako, A. Not all anger is created equal: The impact of the expresser’s culture on the social effects of anger in negotiations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, H.; Shirako, A.; Maddux, W.W. Cultural variance in the interpersonal effects of anger in negotiations. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Yang, G.; Graham, J.L. Tension and trust in international business negotiations: American executives negotiating with Chinese executives. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luomala, H.T.; Kumar, R.; Singh, J.D.; Jaakkola, M. When an intercultural business negotiation fails: Comparing the emotions and behavioral tendencies of individualistic and collectivistic negotiators. Group Decis. Negot. 2015, 24, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopelman, S.; Rosette, A.S. Cultural variation in response to strategic emotions in negotiations. Group Decis. Negot. 2008, 17, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromwell, H.C.; Panksepp, J. Rethinking the cognitive revolution from a neural perspective: How overuse/misuse of the term ‘cognition’ and the neglect of affective controls in behavioral neuroscience could be delaying progress in understanding the BrainMind. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 2026–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brief, A.P.; Weiss, H.M. Organizational behavior: Affect in the workplace. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 279–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, T.A.; Weiss, H.M.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Hulin, C.L. Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and of change. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 356–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopelman, S.; Rosette, A.S.; Thompson, L. The three faces of Eve: Strategic displays of positive, negative, and neutral emotions in negotiations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 2006, 99, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, B.; Fulmer, I.S.; Goates, N. Bargaining with feeling: Emotionality in and around negotiation. In Negotiation Theory and Research; Thompson, L.L., Ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, E.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision-making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1997, 69, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.W. An Introduction to Motivation; Van Nostrand: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.E. Principles of self-regulation: Action and emotion. In Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundations of Social Behavior (Volume 2); Higgins, E.T., Sorrentino, R.M., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 3–52. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E.T. The “self digest”: Self-knowledge serving self-regulatory functions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 1062–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Idson, L.C.; Camacho, C.J.; Higgins, E.T. Promotion and prevention choices between stability and change. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Molden, D.C.; Idson, L.C.; Higgins, E.T. Promotion and prevention focus on alternative hypotheses: Implications for attributional functions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholer, A.A.; Cornwell, J.F.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory focus theory and research. In Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation; Ryan, R.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, P.; Marshall, T.C.; Sadler, P. Promoting success or preventing failure: Cultural differences in motivation by positive and negative role models. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uskul, A.K.; Sherman, D.K.; Fitzgibbon, J. The cultural congruency effect: Culture, regulatory focus, and the effectiveness of gain- vs. loss-framed health messages. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Chirkov, V.I.; Kim, Y.M.; Sheldon, K.M. A cross-cultural analysis of avoidance (relative to approach) personal goals. Psychol. Sci. 2001, 12, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamamura, T.; Meijer, Z.; Heine, S.J.; Kamaya, K.; Hori, I. Approach-Avoidance motivation and information processing: A cross-cultural analysis. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, S.; Choi, H. Culture and motivation: A socio-ecological approach. Adv. Motiv. Sci. 2017, 4, 141–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, P.; Jordan, C.H.; Kunda, Z. Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, T.; Tykocinski, O. Self-discrepancies and biographical memory: Personality and cognition at the level of psychological situation. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Making a good decision: Value from fit. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 1217–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, A. Evaluating faces on trustworthiness: An extension of systems for recognition of emotions signaling approach/avoidance behaviors. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1124, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonnello, V.; Russo, P.M.; Mattarozzi, K. First impression misleads emotion recognition. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonnello, V.; Mattarozzi, K.; Russo, P.M. Emotion recognition in medical students: Effects of facial appearance and care schema activation. Med. Educ. 2019, 53, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A.A.; Kozak, M.N.; Ambady, N. Accurate identification of fear facial expressions predicts prosocial behavior. Emotion 2007, 7, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, P. Universals and cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Cole, J., Ed.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1972; pp. 83–207. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J.M.; Russell, J.A. Do facial expressions signal specific emotions? Judging emotion from the face in context. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. A new pan-cultural facial expression of emotion. Motiv. Emot. 1986, 10, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. An argument for basic emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K.R.; Clark-Polner, E.; Mortillaro, M. In the eye of the beholder? Universality and cultural specificity in the expression and perception of emotion. Int. J. Psychol. 2011, 46, 401–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Culture and the categorization of emotions. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 426–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Is there universal recognition of emotion from facial expressions? A review of the cross-cultural studies. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 102–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.A. Facial expressions of emotion: What lies beyond minimal universality? Psychol. Bull. 1995, 118, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Ellsworth, P.C.; Mesquita, B.; Leu, J.; Tanida, S.; De Veerdonk, E.V. Placing the face in context: Cultural differences in the perception of facial emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, B. Emotions in collectivist and individualist contexts. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, B.; Walker, R. Cultural differences in emotions: A context for interpreting emotional experiences. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, B.; Boiger, M.; De Leersnyder, J. Doing emotions: The role of culture in everyday emotions. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 28, 95–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D.; Olide, A.; Willingham, B. Is there an in-group advantage in recognizing spontaneously expressed emotions? J. Nonverbal Behav. 2009, 33, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.T.; Zhang, X.; Fung, H.H.; Isaacowitz, D.M. Cultural differences in gaze and emotion recognition: Americans contrast more than Chinese. Emotion 2013, 13, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma-Kellams, C.; Blascovich, J. Inferring the emotions of friends versus strangers: The role of culture and self-construal. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R. The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently and Why; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; Widen, S.C.; Russell, J.A. Cultural Differences in Emotion Attribution; Boston College Department of Psychology: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van Kleef, G.A.; De Dreu, C.K.W.; Manstead, A.S.R. The interpersonal effects of emotions in negotiations: A motivated information processing approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.W.; Keltner, D. How emotions work: The social functions of emotional expression in negotiations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2000, 22, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, P.J.; Isen, A.M. The influence of positive affect and visual access on the discovery of integrative solutions in bilateral negotiation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1986, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A.; Fortin, S.P.; Frei, R.L.; Hauver, L.A.; Shack, M.L. Reducing organizational conflict: The role of socially-induced positive affect. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 1990, 1, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A.M.; Daubman, K.A.; Nowicki, G.P. Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allred, K.G.; Mallozzi, J.S.; Matsui, F.; Raia, C.P. The influence of anger and compassion on negotiation performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1997, 70, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, H.; Brett, J.M. Everything in moderation: The social effects of anger depend on its perceived intensity. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 76, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrandt, A.; Barclay, L.J. Comparing integral and incidental emotions: Testing insights from emotions as social information theory and attribution theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 732–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillutla, M.M.; Murnighan, J.K. Unfairness, anger, and spite: Emotional rejections of ultimatum offers. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1996, 68, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J.P. On feeling good and getting your way: Mood effects on negotiator cognition and bargaining strategies. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, B. Intragroup emotion convergence: Beyond contagion and social appraisal. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 24, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsade, S.G.; Coutifaris, C.G.; Pillemer, J. Emotional contagion in organizational life. Res. Organ. Behav. 2018, 38, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N.H. The Emotions; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, P.A.; Guerrero, L.K. Principles of communication and emotion in social interaction. In Handbook of Communication and Emotion; Andersen, P.A., Guerrero, L.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 49–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. Facial expression and emotion. Am. Psychol. 1993, 48, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ames, D.R.; Johar, G.V. I’ll know what you’re like when I see how you feel: How and when affective displays influence behavior-based impressions. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manstead, A.S.; Fischer, A.H.; Jakobs, E.B. The social and emotional functions of facial displays. In Social Context of Nonverbal Behavior; Philippot, P., Feldman, R.S., Coats, E.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 287–313. [Google Scholar]

- van Kleef, G.A. The Interpersonal Dynamics of Emotion: Toward an Integrative Theory of Emotions as Social Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Northcraft, G.B.; van Kleef, G.A. Beyond negotiated outcomes: The hidden costs of anger expression in dyadic negotiation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 2012, 119, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaceur, M.; Kopelman, S.; Vasiljevic, D.; Haag, C. Weep and get more: When and why sadness expression is effective in negotiations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1847–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kleef, G.A.; De Dreu, C.K.W.; Manstead, A.S.R. The interpersonal effects of anger and happiness in negotiations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, G.A.; De Dreu, C.K.W.; Pietroni, D.; Manstead, A.S.R. Power and emotion in negotiation: Power moderates the interpersonal effects of anger and happiness on concession making. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 557–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaerer, M.; Teo, L.; Madan, N.; Swaab, R.I. Power and negotiation: Review of current evidence and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 33, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiedens, L.Z.; Ellsworth, P.C.; Mesquita, B. Stereotypes about sentiments and status: Emotional expectations for high- and low-status group members. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfenbein, H.A.; Foo, M.D.; White, J.; Tan, H.H.; Aik, V.C. Reading your counterpart: The benefit of emotion recognition accuracy for effectiveness in negotiation. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2007, 31, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; DiPaolo, M.; Salovey, P. Perceiving affective content in ambiguous visual stimuli: A component of emotional intelligence. J. Person. Assess. 1990, 54, 772–781. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, K.; Mehu, M.; van Peer, J.M.; Scherer, K.R. Sense and sensibility: The role of cognitive and emotional intelligence in negotiation. J. Res. Person. 2018, 74, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonnello, V.; Carnevali, L.; Russo, P.M.; Ottaviani, C.; Cremonini, V.; Venturi, E.; Mattarozzi, K. Reduced recognition of facial emotional expressions in global burnout and burnout depersonalization in healthcare providers. PeerJ. 2021, 9, e10610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groves, K.S.; Feyerherm, A.; Gu, M. Examining cultural intelligence and cross-cultural negotiation effectiveness. J. Manag. Educ. 2015, 39, 209–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, L.; Gelfand, M.J. The culturally intelligent negotiator: The impact of cultural intelligence CQ on negotiation sequences and outcomes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2010, 112, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, P.C.; Ang, S. Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions Across Cultures; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.P.; Liu, D.; Portnoy, R. A multilevel investigation of motivational cultural intelligence, organizational diversity climate, and cultural sales: Evidence from US real estate firms. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, H.; Brett, J.M. Context matters: The social effects of anger in cooperative, balanced, and competitive negotiation situations. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 61, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, T.A. Collective bargaining and organizational behavior research. Res. Organ. Behav. 1980, 2, 129–176. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, D.; Hwang, H.S. Evidence for training the ability to read microexpressions of emotion. Motiv. Emot. 2011, 35, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D. Cultural similarities and differences in display rules. Motiv. Emot. 1990, 14, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshin, A. The impact of non-normative displays of emotion in the workplace: How inappropriateness shapes the interpersonal outcomes of emotional displays. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, C.M.; Diefendorff, J.M.; Greguras, G.J. Understanding emotional display rules at work and outside of work: The effects of country and gender. Motiv. Emot. 2013, 37, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, R.E.; Caldara, R.; Schyns, P.G. Internal representations reveal cultural diversity in expectations of facial expressions of emotion. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2012, 141, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuki, M.; Maddux, W.W.; Masuda, T. Are the windows to the soul the same in the East and West? Cultural differences in using the eyes and mouth as cues to recognize emotions in Japan and the United States. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.S.; Minson, J.A.; Schöne, M.; Heinrichs, M. In the eye of the beholder: Eye contact increases resistance to persuasion. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 2254–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Sauter, D.A.; van Kleef, G.A. Seeing mixed emotions: The specificity of emotion perception from static and dynamic facial expressions across cultures. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2018, 49, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Cross-Cultural Context | Emotions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adam and Shirako (2013) [56] | East Asian negotiators—European American and Hispanic negotiators | Anger expression (East Asian stereotype: emotionally inexpressive) | Angry East Asian elicits greater cooperation. |

| Adam, Shirako, and Maddux (2010) [57] | Asian and Asian American negotiators—European American negotiators | Anger expression (East Asian emotion display norms: Anger expression is inappropriate.) | Anger expression elicits larger concessions from Westerners and smaller concessions from Easterners. |

| Lee, Yang, and Graham (2006) [58] | Chinese negotiators—American negotiators | Felt tension during negotiations | For Chinese, greater tension increases the likelihood of an agreement, whereas for Americans, the likelihood of an agreement marginally decreases. |

| Luomala, Kumar, Singh, and Jaakkola (2015) [59] | Indian negotiators—Finnish negotiators | Dejection- and agitation-related emotions | Finnish experience more dejection than agitation in an unsuccessful negotiation, followed by reengagement with the opponent to achieve positive outcome. In contrast, Indians report positive or neutral emotions even in an unsuccessful negotiation. |

| Kopelman and Rosette (2008) [60] | East Asian and Hong Kong Asian negotiators—Israeli negotiators | Positive or negative emotion expression East Asian emotion display norms: Positive emotion communicates humility and respect.) | Easterners accept an offer from an opponent who displayed positive emotion. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, D.; Park, H.; Rhee, S.-Y. The Role of Regulatory Focus and Emotion Recognition Bias in Cross-Cultural Negotiation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052659

Han D, Park H, Rhee S-Y. The Role of Regulatory Focus and Emotion Recognition Bias in Cross-Cultural Negotiation. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052659

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Donghee, Hyewon Park, and Seung-Yoon Rhee. 2021. "The Role of Regulatory Focus and Emotion Recognition Bias in Cross-Cultural Negotiation" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052659

APA StyleHan, D., Park, H., & Rhee, S.-Y. (2021). The Role of Regulatory Focus and Emotion Recognition Bias in Cross-Cultural Negotiation. Sustainability, 13(5), 2659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052659