Revitalization of Public Spaces in Cittaslow Towns: Recent Urban Redevelopment in Central Europe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

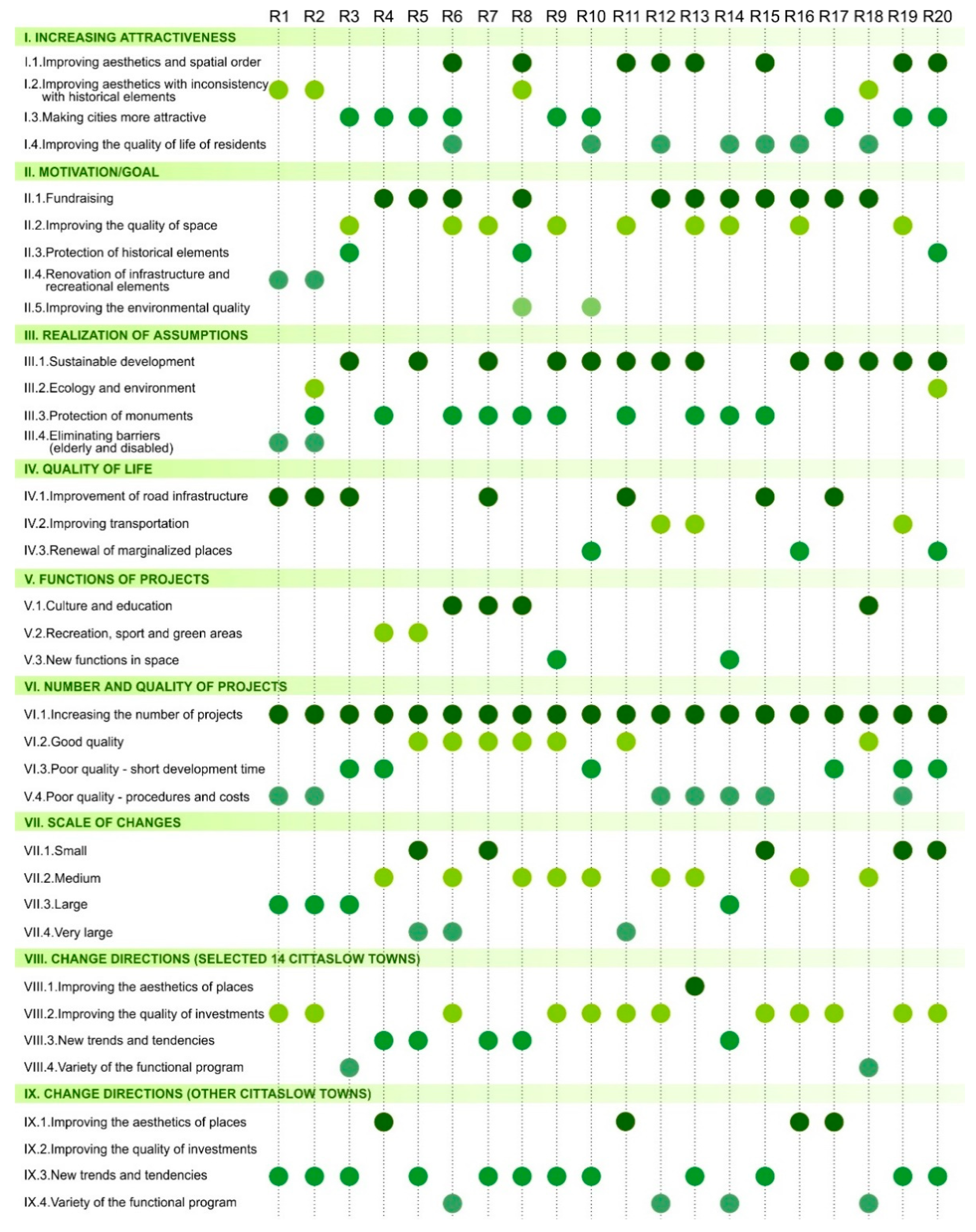

- Did the membership in the Cittaslow town network and the inclusion of towns in the Supra-Local Revitalization Program (SLRP) increase the attractiveness of towns?

- To what extent are the projects implemented under the SLRP directly related to the main goal of Cittaslow towns, i.e., sustainable development and respect for identity?

- What was the main motivation for the revitalization of public spaces?

- What is the perception of changes in urban space after revitalization?

- Is the participation of towns in SLRP related to the increase in the number of projects based on pro-environmental, ecological, and cultural development, as well as their quality and effectiveness?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Revitalization of Small Towns and the Livability Concept

2.2. The Role of the Revitalization Process in the Renewal of Small Towns in Warmia and Mazury

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Assumptions of the Supralocal Revitalization Program

3.2. Research Assumptions

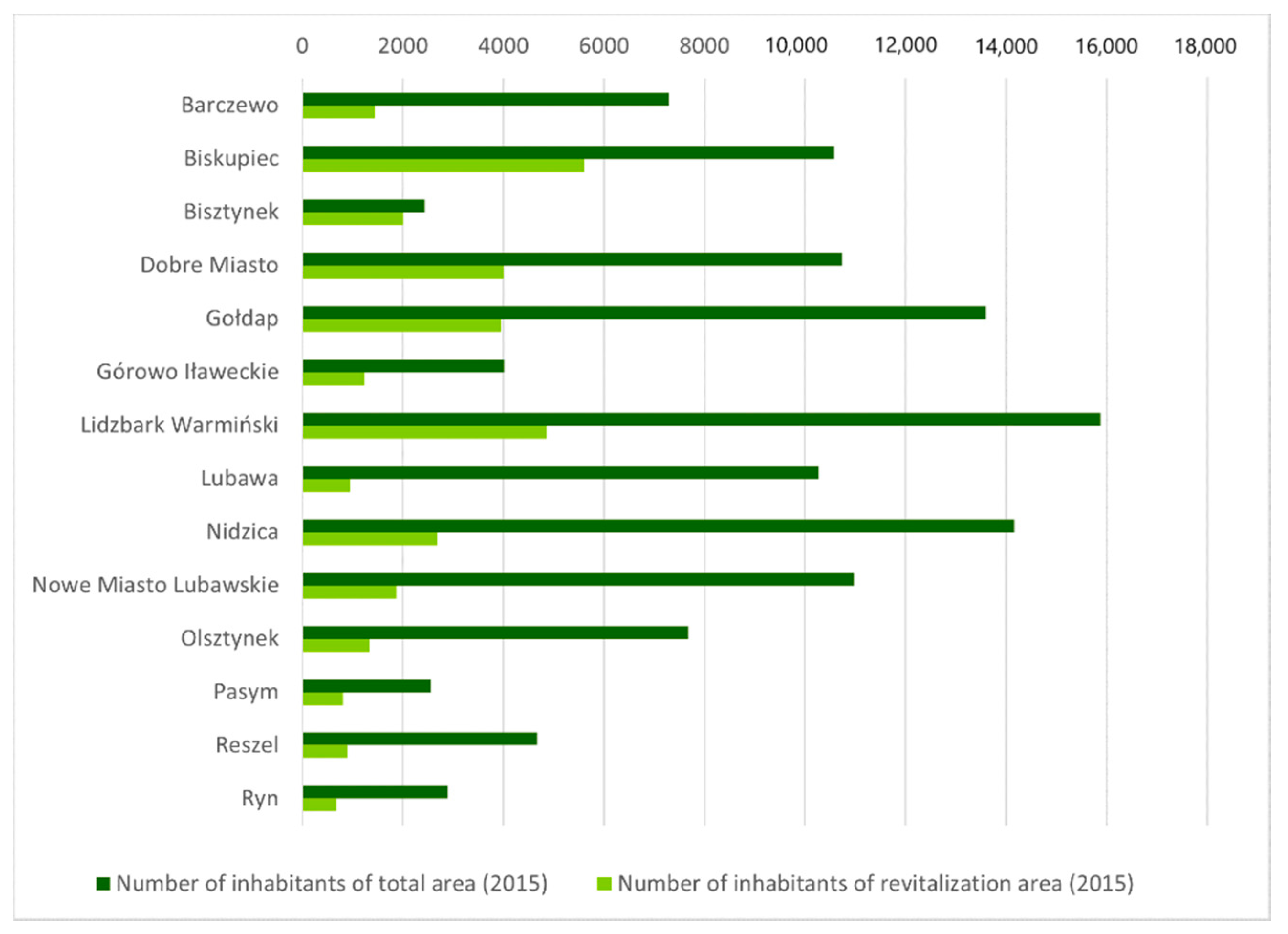

3.3. The Study Area

3.4. Research Stages and Methods

3.4.1. Stage I. Analysis of Materials and Documents Related to Selected Towns

3.4.2. Stage II. Analysis of the Revitalized Area

3.4.3. Stage III. Selection and Analysis of Projects Taking into Account Goals and Functions

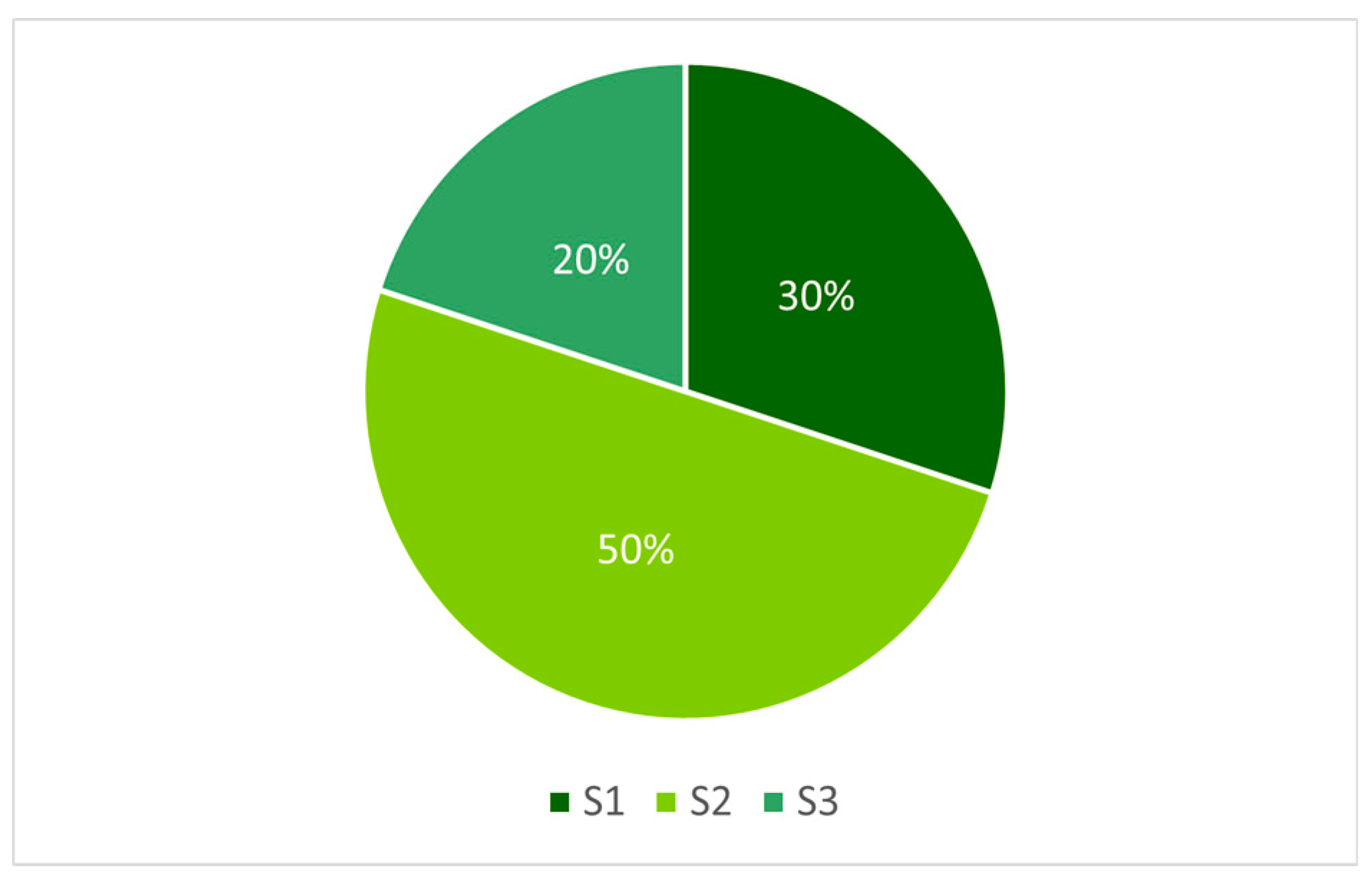

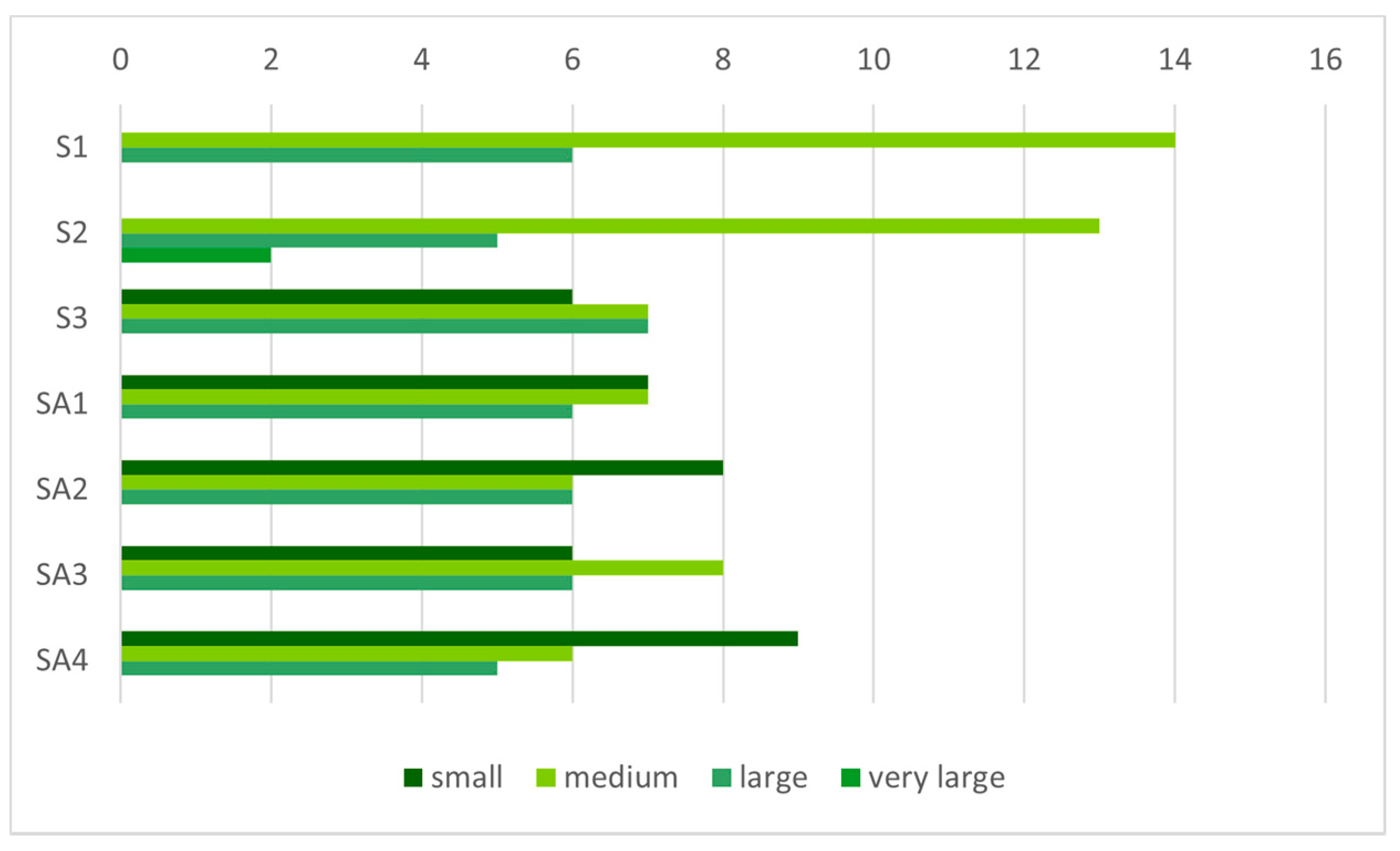

3.4.4. Stage IV. Assessment of the Degree of Development of Public Space in Relation to Projects Related to Space (S), and Architecture and Space (SA)

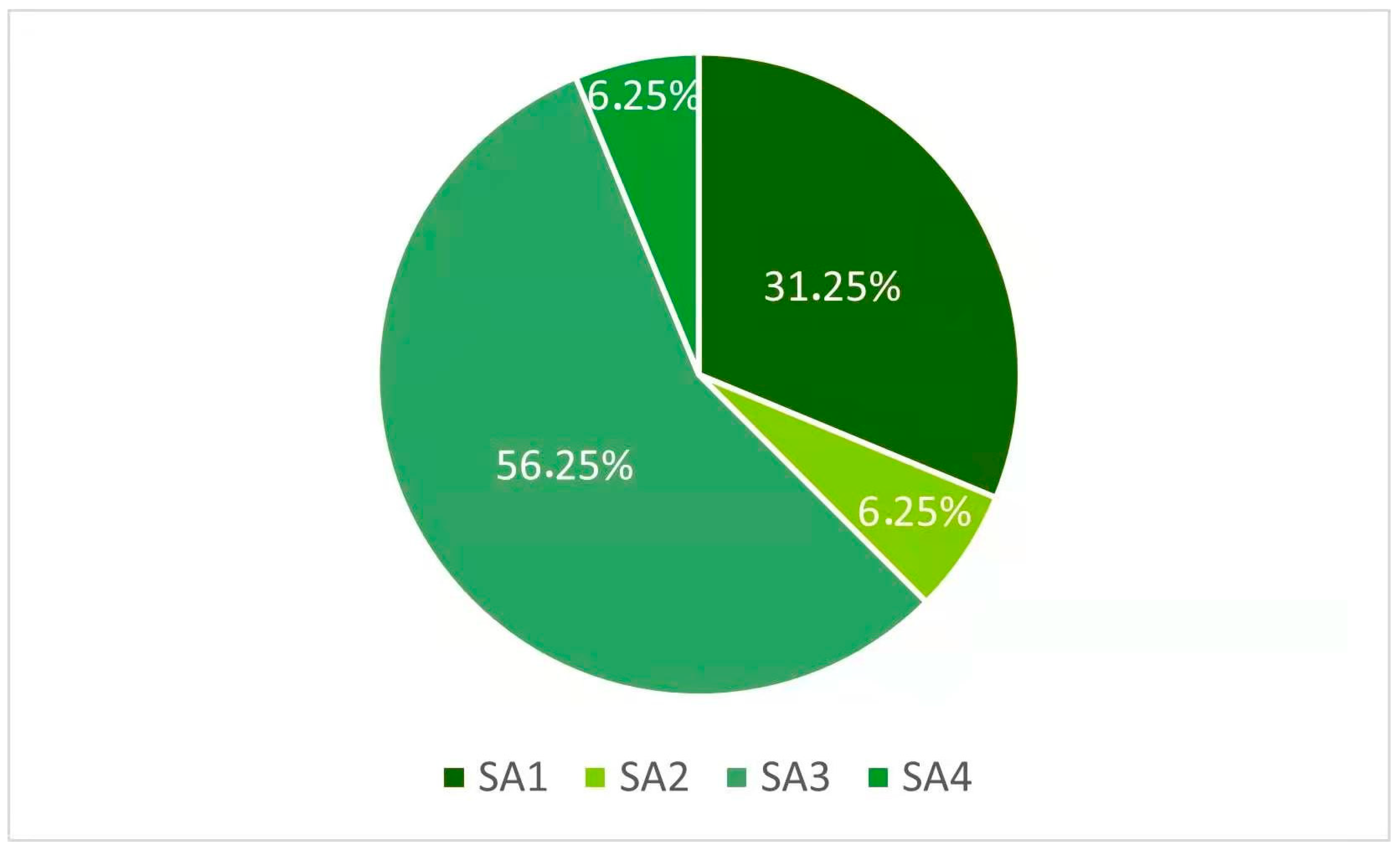

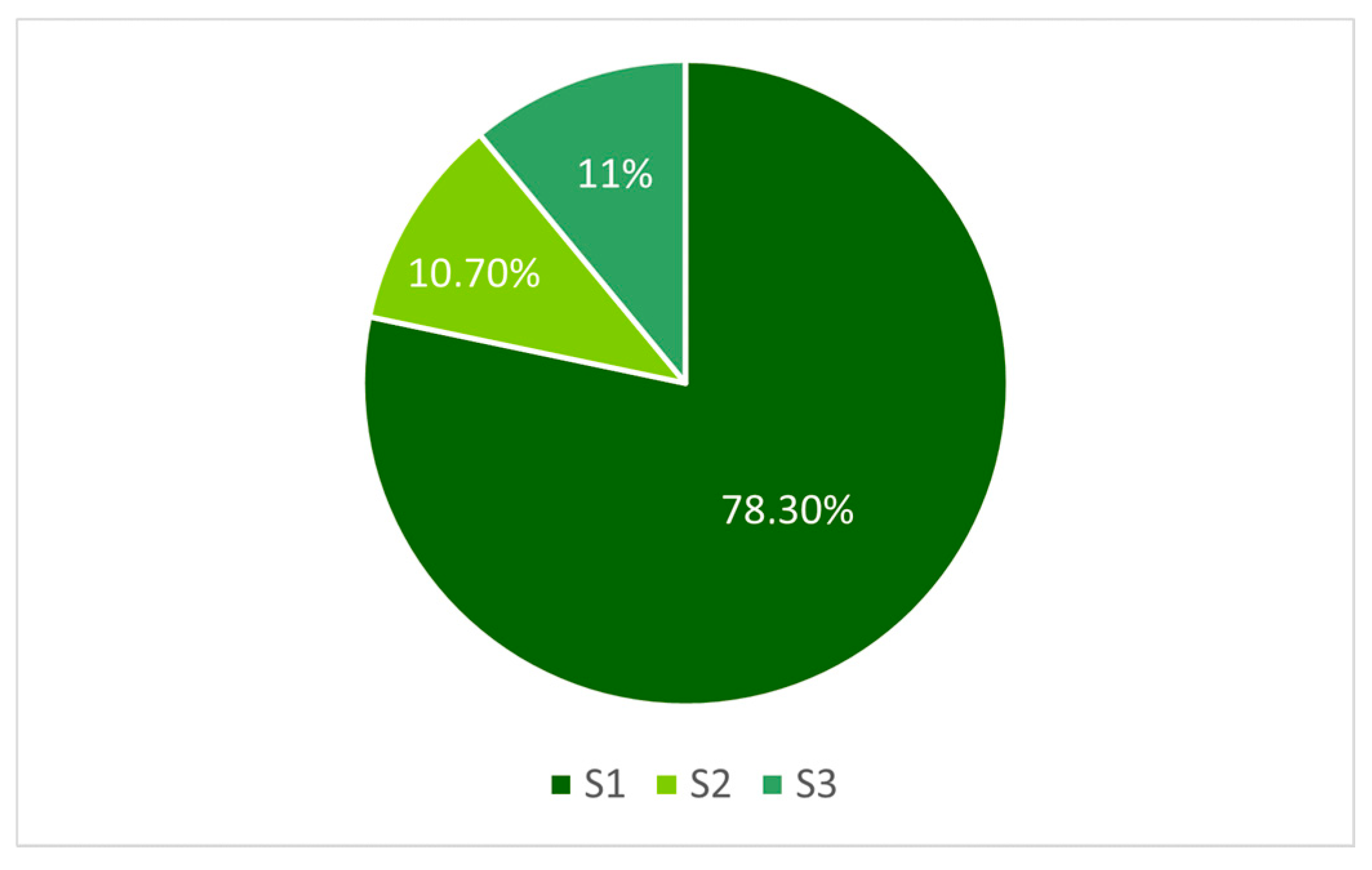

- S1—parks and green squares;

- S2—recreation and sport areas;

- S3—main squares, streets, parking spaces;

- SA1—buildings with a social and administrative (contemporary or with historical value) and surrounding areas;

- SA2—buildings with social/recreational/sports function and surrounding areas;

- SA3—buildings with cultural function (with historical values);

- SA4—buildings with transportation function and surrounded road infrastructure (railways stations and parking spaces).

3.4.5. Stage V. Expert Assessment Regarding the Implementation of Projects

- Knowledge of the revitalization process in the small towns of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship;

- Expert’s ability to assess changes in the public space of the fourteen sites selected for analysis, and thus knowledge of the spatial and functional structure of those sites;

- Experts are not authors or directly involved in the implementation of the projects.

4. Results

4.1. The Results of the Analysis of Source Materials Regarding the Priority Objectives Included in the Supra-Local Revitalization Program

- With regard to the protection of cultural heritage—protection and improvement of cultural heritage objects, restoration or giving them a new function;

- In terms of space renewal—revitalization and modernization of public space, improvement of accessibility of space for disabled or excluded people, improvement of the quality of public space for residents and tourists, revitalization of publicly accessible recreational areas;

- In terms of improvement of infrastructure and residential areas—modernization of technical and road infrastructure, improvement of the accessibility of residential buildings and the environment, thermal modernization of residential buildings;

- In the field of social, educational, and promotional activities—improvement of ecological awareness and pro-ecological attitudes of residents, shaping a positive image of the town, improving conditions for rest and leisure by supporting initiatives for children, youth, and the elderly.

4.2. Results of the Assessment of the Degree of Spatial Development in Relation to the Revitalized Area in Towns

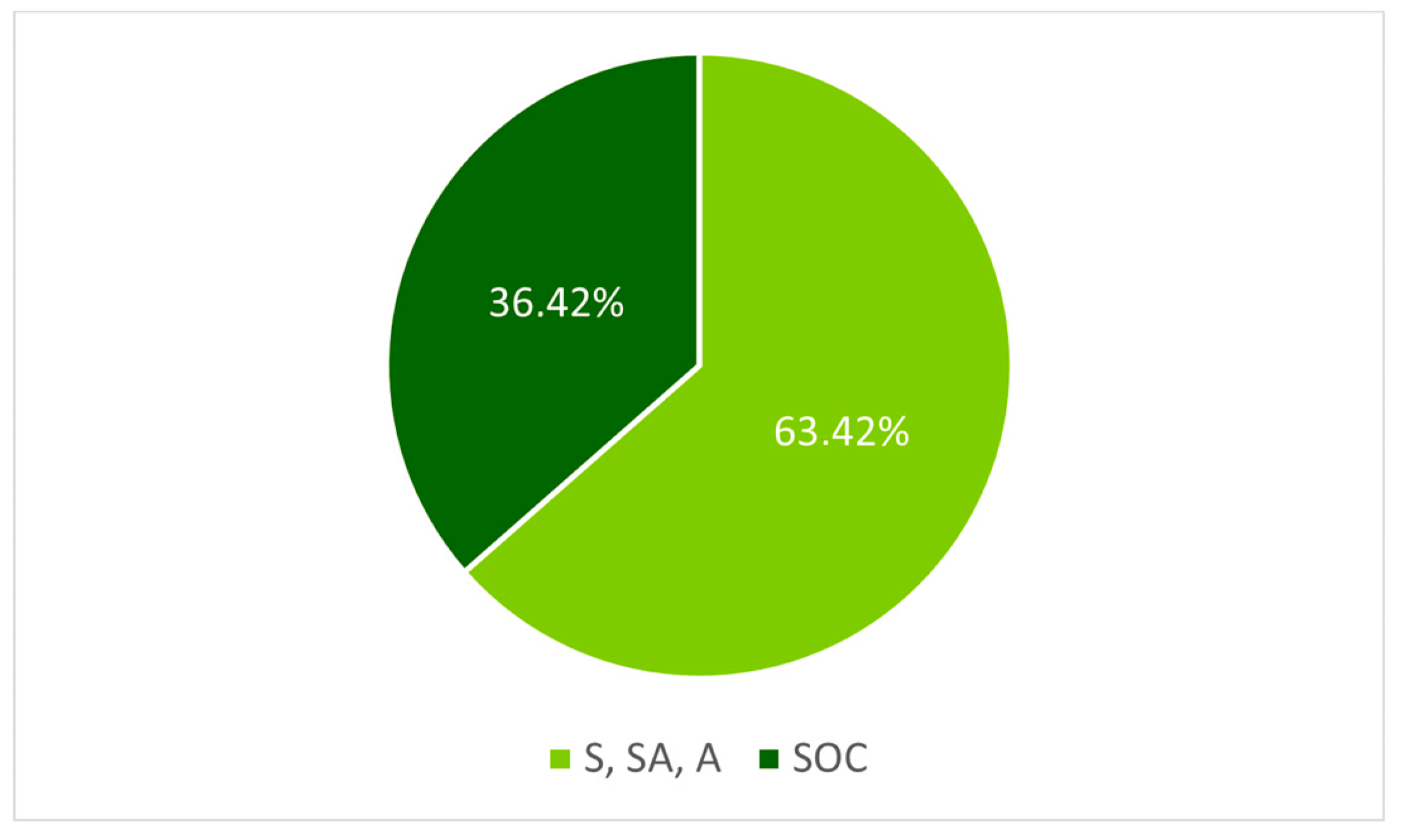

4.3. Results of Analysis of the Projects Taking into Account Goals and Functions

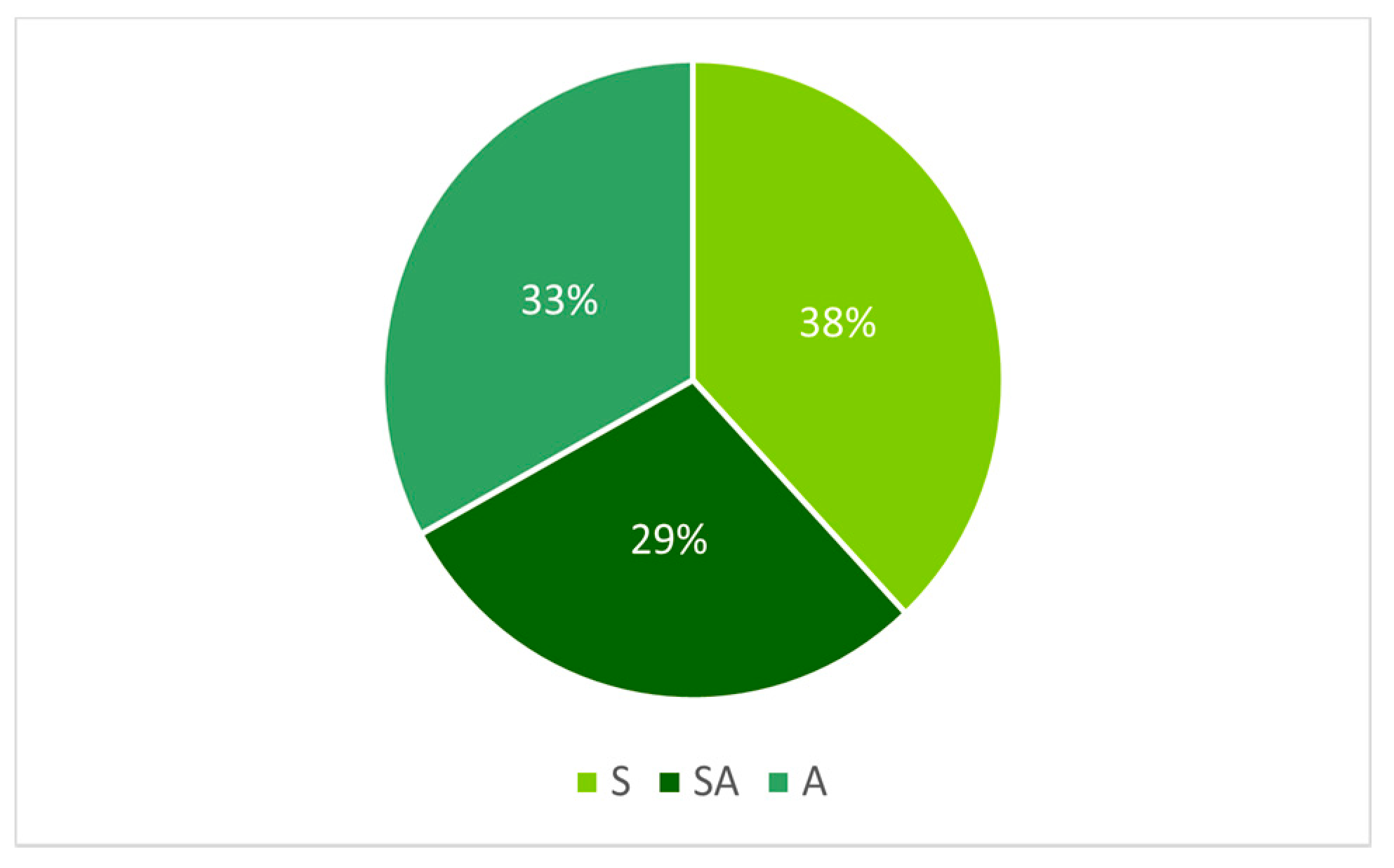

4.4. The Results of the Analysis of Spatial Development Divided into Functions in Groups S and SA

4.5. The Results of Interview with Experts

“…definitely belonging to the Cittaslow network and SLRP made it easier for Cittaslow towns to increase their attractiveness by implementing projects in line with the idea of words…indicated in the program. SLRP Cittaslow allowed promoting towns that share similar issues…”“…the towns become more beautiful, they become a tourist attraction;…the inhabitants live calmer and better…”

“…joining the SLRP has significantly increased the possibilities of improving the aesthetics of public spaces in towns, but there is no care for historical elements…”“…there is a noticeable dissonance between the revitalized areas and the existing tissue, historical buildings or the surrounding landscape;…the point is not to introduce artificially historicizing elements, “pretending that they are from the past”, but to perform revitalization with respect for the existing elements and genius loci…”

“…An important motivation was the pressure of the inhabitants to replace post-communist public spaces with more modern ones; …the motivation was to a small extent to improve the condition of the environment, take care of monuments or protect natural resources…”“…the most important motivation was the possibility of obtaining funds and increasing the quality of life of the inhabitants and changing the image of the revitalized area…”

“…definitely important for the people managing the revitalization process was the improvement of the quality of infrastructure and the renewal of space;…the aesthetics of architectural objects was secondary, if the remaining needs of the residents were not met…”“…especially in the perspective of towns with a low level of investment activity, it was important in the first place to meet the infrastructural needs and adapt the infrastructure to the needs of the resident, meeting the expectations of a town user in the 21st century…”

“…the sphere of culture and the preservation of its tangible and intangible heritage are also very important issues in the perspective of space revitalization in Cittaslow towns…”“…regardless of the age group, it is important to arrange places for various activities, including active (sports, recreational) or passive (walking in silence, relaxing)…”

“…often the possibility of applying for subsidies is very limited in time, hence the need to prepare project documentation in a short time…imposing the will and vision of officials on designers in the absence of public consultations may also be a problem…”“…a disadvantage in the development of the SLRP was a short time that towns had to select the projects and prepare documentation…it could translate into the quality and effectiveness of the projects…”“…the main criterion for selecting contractors is the price, which is not related to quality…often poor quality materials are used…work is carried out quickly, inaccurately, which causes manufacturing defects and the need for repairs…”

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The participation of towns in SLRP undoubtedly brought the intended effects of drawing attention to the need for changes in public spaces and thus taking steps towards their revitalization. This, in turn, increased their attractiveness and influenced the perception of Cittaslow towns as standing out from the rest of the region and the country. This was confirmed, inter alia, by the results of the expert interview.

- The main motivation for the revitalization of public spaces was the possibility of obtaining EU funds for the implementation of projects and the preparation of common places for residents. Most of the projects concerned social function. In contrast, the participation of towns in SLRP did not increase the number of projects based on pro-environmental, ecological, and cultural development.

- Our research shows that the goal of social development and making the revitalized public spaces available to residents has been achieved. However, the implemented projects often did not take into account the objectives of improving ecological conditions or respect for identity on the same level as social objectives. This is important due to the declaration of sustainable development clearly defined in the strategic goals of Cittaslow towns, in the SLRP, and in the revitalization plans of selected towns.

- According to the research, changes in public spaces proceeded quickly, and the prepared projects were not always well thought out and implemented, which resulted in their lower quality and lower efficiency.

- Even distribution of the goals of revitalization, and thus paying attention not only to the economic and social aspect, but also, which is significant nowadays, to the issues of ecology and environmental protection. In future projects, attention should be paid to the specificity of the place and the reference to historical and cultural conditions.

- It is necessary to develop detailed pre-design analyzes, as well as pay attention to the need for a longer design process, allowing for the elimination of errors and the introduction of optimal solutions.

- It is important to conduct reliable interviews with experts, but also with residents in order to develop common goals regarding the use of space.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, D.; Matczak, A. Urbanization in Poland: Tendencies and transformation. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2002, 9, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świąder, M.; Szewrański, S.; Kazak, J. Spatial-temporal diversification of poverty in Wroclaw. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 1596–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foryś, I.; Putek-Szeląg, E. The impact of crime on residential property value—on the example of Szczecin. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2017, 25, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Hoof, J.; Bennetts, H.; Hansen, A.; Kazak, J.K.; Soebarto, V. The Living Environment and Thermal Behaviours of Older South Australians: A Multi-Focus Group Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kajdanek, K. Newcomers vs. Old-Timers? Community, Cooperation and Conflict in the Post-Socialist Suburbs of Wrocław, Poland. In Mobilities and Neighbourhood Belonging in Cities and Suburbs; Watt, P., Smets, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojanek, M.; Tanaś, J.; Trojanek, R. Changes in the Demographic Structure of the Central City in the Light of the Suburbanization Process (The Study of Poznań); SMARTCITY360; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezdeń, P.; Szmytkie, R. Current Changes in the Location of Industry in the Suburban Zone of a Post-Socialist City. Case Study of Wrocław (Poland). Tijds. voor Econ. en Soc. Geog. 2019, 110, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwińska, A.; Böhm, A.; Kudłacz, M. The phenomenon of urban sprawl in modern Poland: Causes, effects and remedies. Zarządzanie Publiczne 2018, 45, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bieda, A. Urban renewal and the value of real properties. Studia Reg. Lokal. 2017, 3, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdipanah, R.; Marra, G.; Melis, G.; Gelormino, E. Urban renewal, gentrification and health equity: A realist perspective. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jackson, C. The effect of urban renewal on fragmented social and political engagement in urban environments. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, J.; Wood, G. Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, D.E. Urban Planning: Central City Revitalization. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Neil, J., Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Imprint Pergamon, Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 16040–16044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlee, M.; Omar, D.; Yunus, R.M.; Samadi, Z. Revitalization of Urban Public Spaces: An Overview. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 201, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tricarico, L. Community action: Value or instrument? An ethics and planning critical review. J. Archit. Urban 2017, 41, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grodach, C.; Ehrenfeucht, R. Urban. Revitalization: Remaking Cities in a Changing World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zielenbach, S. The Art of revitalization. In Improving Condition of Distressed Inner-City Neighborhoods; Garland Publishing Inc.: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.W.; Shen, G.Q.; Wang, H. A review of recent studies on sustainable urban renewal. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spaans, M. The implementation of urban regeneration projects in Europe: Global ambitions, local matters. J. Urban. Des. 2004, 9, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temelová, J. Urban revitalization in central and inner parts of (post-socialist) cities: Conditions and consequences. In Regenerating Urban Core; Ilmavirta, T., Ed.; Center for Urban and Regional Studies C72, Helsinki University of Technology: Espoo, Finland, 2009; pp. 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, R. Urban Renewal in South African Cities. In Urban Geography in South Africa; Massey, R., Gunter, A., Eds.; GeoJournal Library; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Liu, G.; Lang, W.; Shrestha, A.; Martek, I. Strategic approaches to sustainable urban renewal in developing countries: A case study of Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nzimande, N.P.; Fabula, S. Socially sustainable urban renewal in emerging economies: A comparison of Magdolna Quarter, Budapest, Hungary and Albert Park, Durban, South Africa. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2020, 69, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, P. Boston’s “Big Dig” History and Reflection of a 15 Year Highway Construction Project. PSU GEOG 2019, 1, 482. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/c3c18274fcb348af872822e9f2a1887a (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Struct on Green Carpet: Multipurpose Use of Space. Available online: https://strukton.com/en/projects/2019/03/avenue_2 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Bo01, Malmö. Available online: https://www.urbangreenbluegrids.com/projects/bo01-city-of-tomorrow-malmo-sweden/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Jing, Y. Refining and Reappearance: Shanghai South Bund Revitalization. In Proceedings of the 47th ISOCARP Congress, Wuhan, China, 24–28 October 2011; Available online: http://www.isocarp.net/Data/case_studies/1963.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- High Line. Available online: https://www.thehighline.org/ (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Przybyła, K.; Kachniarz, M.; Ramsey, D. The investment activity of cities in the context of their administrative status: A case study from Poland. Cities 2020, 97, 102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, L.; Poelman, H. Cities in Europe the New OECD-EC Definition Regional Focus. A Series of Short Papers on Regional Research and Indicators Produced by the Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy RF 01/2012. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/focus/2012_01_city.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- International Network of Cities Where Living is Good. Available online: https://www.cittaslow.org/ (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Ekinci, M.B. The Cittaslow philosophy in the context of sustainable tourism development; the case of Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.; Knox, P.L. Slow Cities: Sustainable Places in a Fast World. J. Urban. Aff. 2006, 28, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perano, M.; Abbate, T.; La Rocca, E.T.; Casali, G.L. Cittaslow & fast-growing SMEs: Evidence from Europe. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, A.K. Making Small Towns Visible in Europe: The Case of Cittaslow Network—The Strategy Based on Sustainable Development. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, SI, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, J.; Morrison, A. Designing Slow Cities for More than Human Enrichment: Dog Tales—Using Narrative Methods to Understand Co-Performative Place-Making. Multimodal. Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagroba, M.; Szczepańska, A.; Senetra, A. Analysis and Evaluation of Historical Public Spaces in Small Towns in the Polish Region of Warmia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozmen, A.; Can, M.C. The urban conservation approach of Cittaslow Yalvaç. Megaron 2018, 13, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmens, J.; Freeman, C. The value of cittaslow as an approach to local sustainable development: A New Zealand perspective. Int. Plan. Stud. 2012, 17, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revitalization of Cittaslow Town Launched. Available online: https://www.cittaslow.org/news/polish-national-network-revitalization-cittaslow-town-launched (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Regional Operational Programme of the Voivodeship of Warmia and Mazury 2014–2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/regional-innovation-monitor/policy-document/regional-operational-programme-voivodeship-warmia-and-mazury-2014-2020 (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Senetra, A.; Szarek-Iwaniuk, P. Socio-economic development of small towns in the Polish Cittaslow Network—A case study. Cities 2020, 103, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicka, W.; Farelnik, E.; Stanowicka, A. The development of the Polish National Cittaslow Network. Olszt. Econ. J. 2019, 14, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicka, W. Socio-economic potential of cities belonging to the Polish National Cittaslow Network. Oecon. Copernic. 2020, 11, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farelnik, E. Cooperation of slow cities as an opportunity for the development: An example of Polish National Cittaslow Network. Oecon. Copernic. 2020, 11, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maćkiewicz, B.; Konecka-Szydłowska, B. Green tourism: Attractions and initiatives of polish Cittaslow cities. In Tourism in the city; Bellini, N., Pasquinelli, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 297–309. [Google Scholar]

- Supralocal Program of Revitalisation of Cittaslow Towns. Ponadlokalny Program Rewitalizacji Miast Cittaslow. 2019. Available online: https://cittaslowpolska.pl/images/PDF/PPR_08_2019.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Strzelecka, E. Network model of revitalization in the Cittaslow cities of the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodship. Barometr. Reg. 2018, 16, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, A.; Layton, J. Social infrastructure and the public life of cities: Studying urban sociality and public spaces. Geogr. Compass 2019, 13, e12444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinenberg, E. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life; Penguin: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, J.; Pollock, V.; Paddison, R. Just Art for a Just City: Public Art and Social Inclusion in Urban Regeneration. Urban Studies 2005, 42, 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachour, D.W. Socioeconomic impact of urban redevelopment in inner city of Ningbo. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2006, 7, 1386–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpopi, C.; Manole, C. Integrated Urban Regeneration—Solution for Cities Revitalize. Procedia Econ. 2013, 6, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zagroba, M. Issues of the Revitalization of Historic Centres in Small Towns in Warmia. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kristianova, K.; Jaszczak, A. Historical Centers of Small Cities in Slovakia—Problems and Potentials of Creating Livable Public Spaces. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 022012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramarova, Z.; Kankovsky, A. Mobility in Public Spaces of Small Towns in the Czech Republic. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 042090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Cowley, J. Sidewalk Planning and Policies in Small Cities. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2006, 132, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xu, J.; Shen, Q.; Shi, F.; Chen, Y. Travel mode choices in small cities of China: A case study of Changting. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2018, 59, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.L.; Heinen, E.; Krizek, K. Cycling in small cities. In Cycling for Sustainable Transport: International Trends and Policies; Pucher, J., Buehler, R., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.; Handy, S.; Mokhtarian, P. Factors associated with proportions and miles of bicycling for transportation and recreation in six small us cities. Transp. Res. D 2010, 15, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Audikana, A.; Ravalet, E.; Baranger, V.; Kaufmann, V. Implementing bikesharing systems in small cities: Evidence from the Swiss experience. Transp Policy (Oxf) 2017, 55, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczak, A.; Morawiak, A.; Zukowska, J. Cycling as a sustainable transport alternative in polish cittaslow towns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, M.Z. Reconciling Livability and Sustainability: Conceptual and Practical Implications for Planning. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2015, 35, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruth, M.; Franklin, R.S. Livability for all? Conceptual limits and practical implications. Appl Geogr 2014, 49, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kovacs-Györi, A.; Cabrera-Barona, P.; Resch, B.; Mehaffy, M.; Blaschke, T. Assessing and Representing Livability through the Analysis of Residential Preference. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Kamp, I.; Leidelmeijer, K.; Marsman, G. Urban environmental quality and human well-being: Towards a conceptual framework and demarcation of concepts; a literature study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 65, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothencz, G.; Kolcsár, R.; Cabrera-Barona, P.; Szilassi, P. Urban green space perception and its contribution to well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jančová, N. New approaches for research public spaces and urban green infrastructure in the context of livable urban environment. In Proceedings of the INTED 2019 Conference Proceedings, Valencia, Spain, 11–13 March 2019; pp. 3829–3832. [Google Scholar]

- Dushkova, D.; Haase, D. Not Simply Green: Nature-Based Solutions as a Concept and Practical Approach for Sustainability Studies and Planning Agendas in Cities. Land 2020, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Jagt, A.P.N.; Raven, R.; Dorst, H.; Runhaar, H. Nature-based innovation systems. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 35, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchur, A.; Lobikava, N.; Lobikava, V. Revitalization of (Post-) Soviet Neighbourhood with Nature-Based Solutions. AHR 2020, 23, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N. Seven lessons for planning nature-based solutions in cities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 93, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwierzchowska, I.; Fagiewicz, K.; Poniży, L.; Lupa, P.; Mizgajski, A. Introducing nature-based solutions into urban policy—facts and gaps. Case study of Poznań. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, C.; Grant, A.; Millward, A.A.; Steenberg, J.; Sabetski, V. Developing Performance Indicators for Nature-Based Solution Projects in Urban Areas: The Case of Trees in Revitalized Commercial Spaces. CATE 2019, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, S.; Chu, E.K.; Mason, S.G. Climate Change in Cities. Innovations in Multi-Level Governance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krauze, K.; Wagner, I. From classical water-ecosystem theories to nature-based solutions—Contextualizing nature-based solutions for sustainable city. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, G.; Pooley, A.; Pascale, F. A Community-Driven Nature-Based Design Framework for the Regeneration of Neglected Urban Public Spaces. In Sustainable Ecological Engineering Design; Scott, L., Dastbaz, M., Gorse, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; Bonn, A. Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban. Areas—Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice; Springer Open: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Rodriguez, R.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Barau, A.S. Sustainable Development Goals and climate change adaptation in cities. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, M.; Juhola, S.; Klein, J. The role of scale in integrating climate change adaptation and mitigation in cities. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 741–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shade, C.; Kremer, P.; Rockwell, J.S.; Henderson, K.G. The effects of urban development and current green infrastructure policy on future climate change resilience. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagrum, A.E.; Andenæs, E.; Kvande, T.; Lohne, J. Climate Change Adaptation Measures for Buildings—A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roggema, R. Adaptation to Climate Change: A Spatial Challenge; Springer: Dordrecht The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 211–251. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, M.B.H. Coupling of Economic Benefits and Climate Change Adaptation: Reflection from a Small Municipality Development Plan. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 241, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannenberg, A.L.; Frumkin, H.; Hess, J.J.; Ebi, K.L. Managed retreat as a strategy for climate change adaptation in small communities: Public health implications. Clim. Chang. 2019, 153, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picketts, I.M.; Déry, S.J.; Curry, J.A. Incorporating climate change adaptation into local plans. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 984–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, D.C.; Juhola, S. Guidance for climate change adaptation in small coastal towns and cities: A new challenge. J. Urban. Plan. Dev. 2016, 142, 2516001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, T.; Koziol, K. New Policy Approaches for Increasing Response to Climate Change in Small Rural Municipalities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalbarczyk, E.; Kalbarczyk, R. Typology of Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Polish Cities up to 2030. Land 2020, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiho, S.; Mäki, E.; Wessberg, N.; Paavola, M.; Tuominen, P.; Antikainen, M.; Heikkilä, J.; Rozado, C.A.; Jung, N. Towards circular cities—Conceptualizing core aspects. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 59, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Circular cities. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 2746–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. A Theoretical Framework for Circular Economy Research in the Built Environment. In Building Information Modelling, Building Performance, Design and Smart Construction; Dastbaz, M., Gorse, C., Moncaster, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassens, D.; Kębłowski, W.; Lambert, D. Placing cities in the circular economy: Neoliberal urbanism or spaces of socio-ecological transition? Urban. Geogr. 2020, 41, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit-Boix, A.; Leipold, S. Circular economy in cities: Reviewing how environmental research aligns with local practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1270–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, V.; Towa, E.; Degrez, M.; Achten, W.M.J. Urban waste flows and their potential for a circular economy model at city-region level. Waste Manag. 2019, 83, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sołtysik, M.; Mazur-Belzyt, K. City Space Recycling: The Example of Brownfield Redevelopment. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 042016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basova, S.; Sopirova, A.; Kristianova, K. Potential of Recycling Urban Territories. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 092053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaja, M. Social Aspects of Revitalization of Urban Public Spaces. EJSM 2018, 28, 463–469. [Google Scholar]

- Polatoğlu, Ç.; Çıtak, C.; Kararmaz, Ö. Enhancing Socio-cultural and Socio-economic Values with Architectural Design—Revitalization of Place. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference Design Principles and Practices, Advocacy in Design: Engagement, Commitment and Action, New York, NY, USA, 11–13 November 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jayne, M.; Gibson, C.; Waitt, G.; Bell, D. The Cultural Economy of Small Cities. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, A. Sustaining small cities through leisure, culture and the experience economy. In Cultural Political Economy of Small Cities; Lorentzen, A., van Heur, B., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2013; pp. 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Środa-Murawska, S.; Biegańska, J.; Dąbrowski, L. Perception of the role of culture in the development of small cities by local governments in the context of strategic documents—A case study of Poland. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2017, 38, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sepe, M. Urban transformation, socio-economic regeneration and participation: Two cases of creative urban regeneration. Int. J. Urban. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 6, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Środa-Murawska, S.; Szczepańska, A.; Biegańska, J.; Senetra, A. The phenomenon of non-governmental organizations—new stimuli for cultural development in rural areas in Poland. In Proceedings of the Annual 20th ISC Research for Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia, 21–23 May 2014; pp. 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Tylman, A. Participatory Revitalisation as the Determinant of Changes in Urban Policy Financing. Entrep. Manag. 2017, 8, 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Revitalization Act of 9th of October 2015. Available online: https://www.infor.pl/akt-prawny/DZU.2015.215.0001777,ustawa-o-rewitalizacji.html (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Jaszczak, A. Przyszłość miast Cittaslow. Archit. Kraj. 2015, 1, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Social and Economic Strategy of the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship until 2015. Available online: https://bip.warmia.mazury.pl/3/strategia-rozwoju-spoleczno-gospodarczego-wojewodztwa-warminsko-mazurskiego.html (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Lordkipanidze, M.; Brezet, H.; Backman, M. The entrepreneurship factor in sustainable tourism development. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, N. Outlining triple bottom line contexts in urban tourism regeneration. Cities 2016, 53, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T. Back from the brink: The revitalization of inactive entrepreneurial ecosystems. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2019, 12, e00140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkienè, J.; Kromalcas, S. Concept, directions and practice of city attractiveness improvement. Viešoji Politika ir Administravimas (Public Policy and Administration) 2010, 31, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, M.D. Creative cities and cultural spaces: New perspectives for city tourism. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2010, 4, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusiak, J. Revitalizing urban revitalization in Poland: Towards a new agenda for research and practice. UDI 2019, 63, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parysek, J.J. Urban Revitalization in Poland: Problems, Dilemmas, Challenges and Hopes. Studia Reg. 2017, 50, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc, T. Organisational aspects of execution of the local revitalisation programmes in the largest cities in Poland—indication of directions of further research. In Systems Supporting Production Engineering; Review of problems and solutions; Kaźmierczak, J., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Pa Nova: Gliwice, Poland, 2014; pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Belniak, S. A partnership of public and private sectors as a model for the implementation of urban revitalization projects. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2008, 1, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babis, H.; Janowski, M. Revitalisation of problem areas as an instrument for social and economic activity in the Polish municipalities. EJSM 2018, 28, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortezza, R.; Chen, J.; Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C.; Randrup, T.B. Nature-based solutions for resilient landscapes and cities. Environ. Res. 2018, 165, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farelnik, E. Determinants of the development of slow cities in Poland. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu 2020, 64, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczak, A.; Kristianova, K. Social and Cultural Role of Greenery in Development of Cittaslow Towns. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 603, 032028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczak, A.; Kristianova, K.; Sopirova, A. Revitalization of public space in small towns: Examples from Slovakia and Poland. Zarządzanie Publiczne 2019, 45, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Town | Number of Inhabitants 1 |

|---|---|

| Barczewo | 7290 |

| Biskupiec | 10,582 |

| Bisztynek | 2437 |

| Dobre Miasto | 10,741 |

| Gołdap | 13,593 |

| Górowo Iławeckie | 4021 |

| Lidzbark Warmiński | 15,877 |

| Lubawa | 10,269 |

| Nidzica | 14,166 |

| Nowe Miasto Lubawskie | 10,977 |

| Olsztynek | 7669 |

| Pasym | 2561 |

| Reszel | 4667 |

| Ryn | 2899 |

| No. | Town | Together (with Social) * | ** Without Social | Architecture (A) | Space (S) | Architecture and Space (SA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barczewo * | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | Biskupiec | 5 | 3 | - | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | Bisztynek | 4 | 2 | 1 | - | 1 |

| 4 | Dobre Miasto | 3 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | Gołdap | 13 | 5 | 4 | 1 | - |

| 6 | Górowo Iław. | 6 | 4 | - | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | Lidzbark Warm. | 10 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 8 | Lubawa | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 9 | Nidzica | 6 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| 10 | Nowe Miasto Lub. | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 | - |

| 11 | Olsztynek | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | Pasym | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | - |

| 13 | Reszel | 3 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | Ryn | 6 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 82 | 52 | 17 | 20 | 15 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaszczak, A.; Kristianova, K.; Pochodyła, E.; Kazak, J.K.; Młynarczyk, K. Revitalization of Public Spaces in Cittaslow Towns: Recent Urban Redevelopment in Central Europe. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052564

Jaszczak A, Kristianova K, Pochodyła E, Kazak JK, Młynarczyk K. Revitalization of Public Spaces in Cittaslow Towns: Recent Urban Redevelopment in Central Europe. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052564

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaszczak, Agnieszka, Katarina Kristianova, Ewelina Pochodyła, Jan K. Kazak, and Krzysztof Młynarczyk. 2021. "Revitalization of Public Spaces in Cittaslow Towns: Recent Urban Redevelopment in Central Europe" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052564

APA StyleJaszczak, A., Kristianova, K., Pochodyła, E., Kazak, J. K., & Młynarczyk, K. (2021). Revitalization of Public Spaces in Cittaslow Towns: Recent Urban Redevelopment in Central Europe. Sustainability, 13(5), 2564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052564