The Kalimantan Forest Fires: An Actor Analysis Based on Supreme Court Documents in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

3. Literature Review

Social Fire Network Analysis

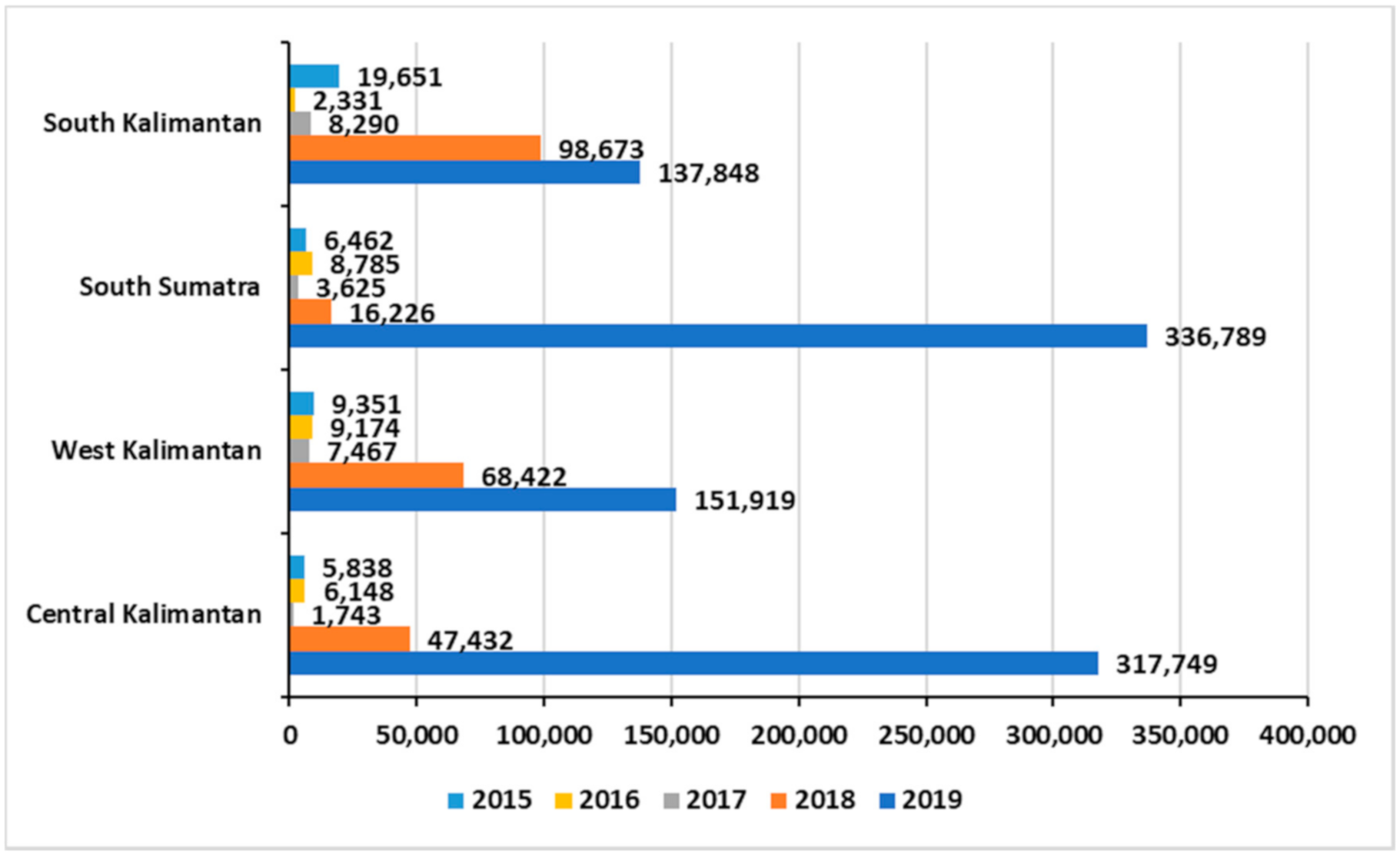

4. Results

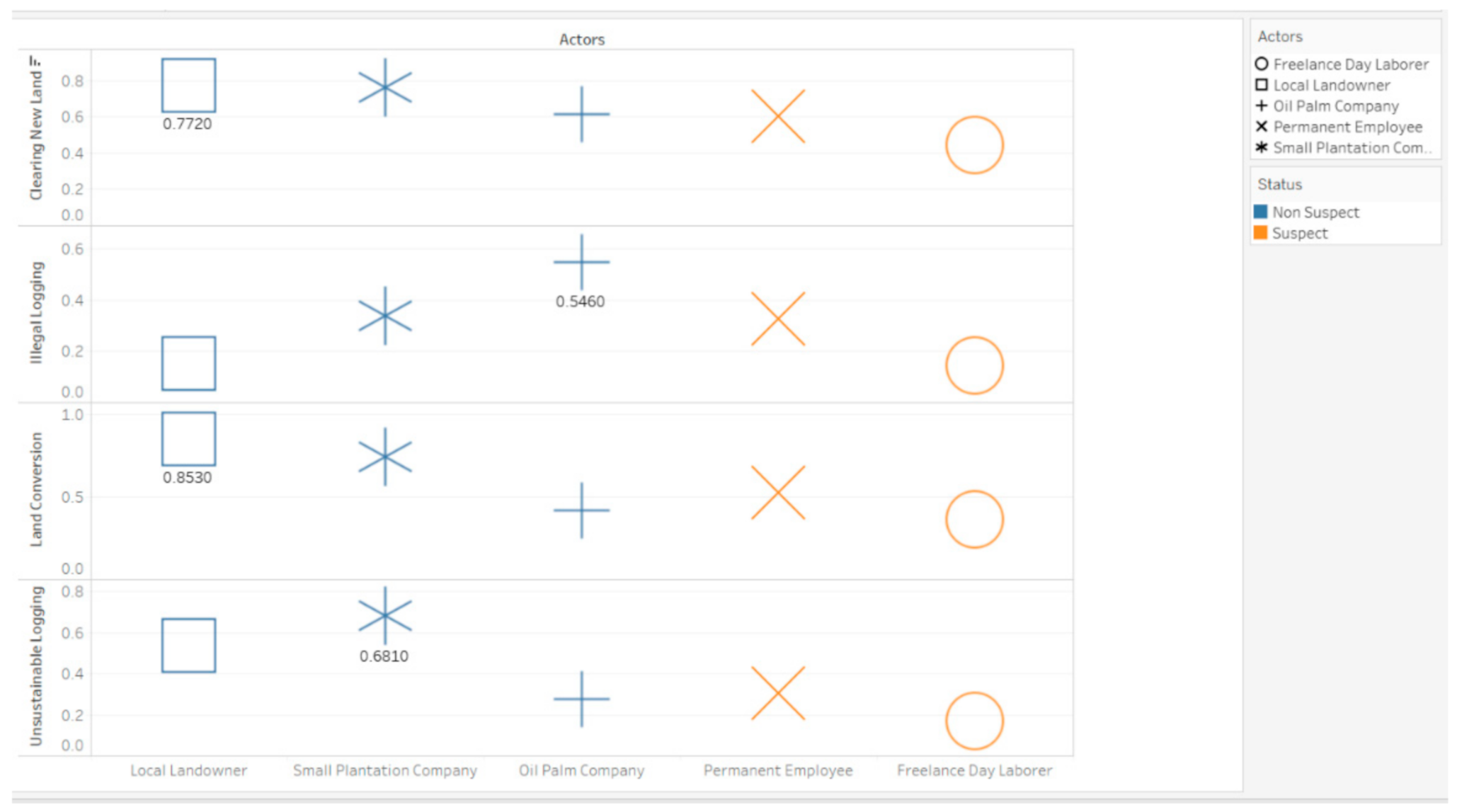

Local Actor Network in Forest Fire Cases

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Austin, K.G.; Schwantes, A.; Gu, Y.; Kasibhatla, P.S. What causes deforestation in Indonesia? Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 024007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, E.P.; Ramdani, R.; Agustiyara, Q.P.; Tomaro, V.; Samidjo, G.S. Land ownership transformation before and after forest fires in Indonesian palm oil plantation areas. J. Land Use Sci. 2019, 14, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uda, S.K.; Hein, L.; Atmoko, D. Assessing the health impacts of peatland fires: A case study for Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 31315–31327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauf, R.; Prayuda, R.; Rahman, K.; Fitra Yuza, A. Civil Society’s Participatory Models: A Policy of Preventing Land and Forest Fire in Indonesia. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2020, 14, 1030–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Agustiyara; Roengtam, S.; Nurmandi, A.; Purnomo, E.P. Collaborative Management between Central and Local Government for Forest Land-use Management. In Proceedings of the ICONPO: International Conference on Public Organization, IPDN Jatinangor, Bandung, Indonesia, 22–23 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- BNBP. Rekapitulasi Luas Kebakaran Hutan dan Lahan (Ha) Per Provinsi Di Indonesia Tahun 2014–2019. Karhutla Monit. Sist. 2019, 1, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Özokcu, S.; Özdemir, Ö. Economic growth, energy, and environmental Kuznets curve. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, E.P.; Ramdani, R.; Salsabila, L.; Choi, J.W. Challenges of community-based forest management with local institutional differences between South Korea and Indonesia. Dev. Pract. 2020, 30, 1082–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, R.; Lounela, A.K. Palm oil expansion in tropical peatland: Distrust between advocacy and service environmental NGOs. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammelli, F.; Coudel, E.; de Freitas Navegantes Alves, L. Smallholders’ Perceptions of Fire in the Brazilian Amazon: Exploring Implications for Governance Arrangements. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 47, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A.; Hamann, A.; Armstrong, G.W.; Acuna-Castellanos, D. Identifying local actors of deforestation and forest degradation in the Kalasha valleys of Pakistan. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 104, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edhlund, B.; McDougall, A. NVivo 12 essentials; Form & Kunskap, AB: Stallarholmen, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.W.; Park, S. An exploratory approach to a Twitter-based community centered on a political goal in South Korea: Who organized it, what they shared, and how they acted. New Media Soc. 2014, 16, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.B.; Naylor, R.L.; Higgins, M.M.; Falcon, W.P. Causes of Indonesia’s forest fires. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. Local Actors in Global Politics. Curr. Sociol. 2017, 52, 649–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzemko, C.; Britton, J. Policy, politics and materiality across scales: A framework for understanding local government sustainable energy capacity applied in England. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 62, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gregorio, M.; Fatorelli, L.; Paavola, J.; Locatelli, B.; Pramova, E.; Nurrochmat, D.R.; May, P.H.; Brockhaus, M.; Sari, I.M.; Kusumadewi, S.D. Multi-level governance and power in climate change policy networks. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 54, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, U.; Buffa, F.; Notaro, S. Community participation, natural resource management and the creation of innovative tourism products: Evidence from Italian networks of reserves in the Alps. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.; Loucks, L.; Berkes, F.; Armitage, D. Community science: A typology and its implications for governance of social-ecological systems. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 106, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theesfeld, I.; Dufhues, T.; Buchenrieder, G. The effects of rules on local political decision-making processes: How can rules facilitate participation? Policy Sci. 2017, 50, 675–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento Barletti, J.P.; Larson, A.M.; Hewlett, C.; Delgado, D. Designing for engagement: A Realist Synthesis Review of how context affects the outcomes of multi-stakeholder forums on land use and/or land-use change. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Torres, H.L.; Pérez-Salicrup, D.R.; Castillo, A.; Ramírez, M.I. Fire Management in a Natural Protected Area: What Do Key Local Actors Say? Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.; Henseler, J.; Castillo, A.; Schuberth, F. Information & Management How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: Guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103168. [Google Scholar]

- Armenteras, D.; Espelta, J.M.; Rodríguez, N.; Retana, J. Deforestation dynamics and drivers in different forest types in Latin America: Three decades of studies (1980–2010). Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 46, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, H.; Shantiko, B.; Sitorus, S.; Gunawan, H.; Achdiawan, R.; Kartodihardjo, H.; Dewayani, A.A. Fire economy and actor network of forest and land fires in Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 78, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, G.M.; Anandi, C.A.M. Shifting cultivation, contentious land change and forest governance: The politics of swidden in East Kalimantan. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 44, 1066–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, A.; Maryudi, A. Development narratives, notions of forest crisis, and boom of oil palm plantations in Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 73, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminah; Krah, C.Y.; Perdinan. Forest fires and management efforts in Indonesia (a review). In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation: “Industrial Forests and Oil Palm Plantation Fires: Impacts and Valuation of the Environmental Losses”, Bogor, Indonesia, 19 November 2019; IOP Publishing Ltd: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aminingrum, A. Forest fire contest: The case of forest fire policy design in Indonesia. Master’s Thesis, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Beel, D.; Jones, M.; Rees Jones, I. Elite city-deals for economic growth? Problematizing the complexities of devolution, city-region building, and the (re)positioning of civil society. Sp. Polity 2018, 22, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dömös, M.; Tarrósy, I. Integration of Migrants in Italy: Local Actors and African Communities. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2020, 26, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.J.; Wright, G.D.; Andersson, K.P. Local Politics of Forest Governance: Why NGO Support Can Reduce Local Government Responsiveness. World Dev. 2017, 92, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopkey, B.; Parent, M.M. The governance of Olympic legacy: Process, actors and mechanisms. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, J.M.D.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Perceptions of local communities on mangrove forests, their services and management: Implications for Eco-DRR and blue carbon management for Eastern Samar, Philippines. J. For. Res. 2020, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.L.; Higgins, M.M. The political economy of biodiesel in an era of low oil prices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Carrington, P.J. The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis; SAGE Publ. limited.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Mehra, A.; Brass, D.J.; Labianca, G. Network analysis in the social sciences. Science 2009, 323, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, T.H.; Crawford, T.H. Actor-Network Theory. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Sidhu, A.; Beacom, A.M.; Valente, T.W. Social Network Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, M.; Lauren, E.; Hon, E.S.; Birmingham, W.C.; Xu, J.; Su, S.; Hon, S.D.; Park, J.; Dang, P.; Lipsky, M.S. Social network analysis of COVID-19 sentiments: Application of artificial intelligence. J. Med. Int. Res. 2020, 22, e22590. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, R.X.; Wang, X.; Shang, K.; Herrera, F. Social network analysis-based conflict relationship investigation and conflict degree-based consensus reaching process for large scale decision making using sparse representation. Inf. Fusion 2019, 50, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimóthy, S.; Dredge, D. Definitions and Mapping the Landscape in the Collaborative Economy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Freggie, G. Mapping discourse coalitions in the minimum unit pricing for alcohol debate: A discourse network analysis of UK newspaper coverage-Fergie-2019-Addiction-Wiley Online Library. 2019. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/add.14514 (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Purnomo, E.P.; Ramdani, R.; Salsabila, L.; Choi, J.W. Challenges of community-based forest management with local institutional differences between South Korea and Indonesia. Dev. Pract. 2020, 30, 1082–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Durresi, A.; Alfantoukh, L. Using Twitter trust network for stock market analysis. Knowledge-Based Syst. 2018, 145, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunadi, A.; Gunardi, G.; Martono, M. The Law Of Forest In Indonesia: Prevention And Suppression Of Forest Fires. Bina Huk. Lingkung. 2019, 4, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sawit Watch. Hentikan Perbudakan Di Perkebunan Sawit—Sawit Watch. 2014. Available online: https://sawitwatch.or.id/2014/11/19/hentikan-perbudakan-di-perkebunan-sawit/ (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Katadata. Kelapa Sawit Sebagai Penopang Perekonomian Nasional—Berita Katadata.co.id. Katadata.co.id. 2019. Available online: https://katadata.co.id/berita/2019/10/07/kelapa-sawit-sebagai-penopang-perekonomian-nasional (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Bradley, T.; Ziniel, C. Green governance? Local politics and ethical businesses in Great Britain. Bus. Ethics 2017, 26, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delman, J. Performance Reviews, Public Accountability, and Green Governance in Hangzhou; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.; Gui, Y.; Xie, Z.; Liu, L. Green Governance and International Business Strategies of Emerging Economies’ Multinational Enterprises: A Multiple-Case Study of Chinese Firms in Pollution-Intensive Industries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Name |

|---|---|

| 1. | Decree No. 33 of 2017 |

| 2. | Decree No. 36 of 2017 |

| 3. | Decree No. 62 of 2019 |

| 4. | Decree No. 114 of 2018 |

| 5. | Decree No. 118 of 2016 |

| 6. | Decree No. 213 of 2018 |

| 7. | Decree No. 242 of 2019 |

| 8. | Decree No. 448 of 2013 |

| 9. | Decree No. 698 of 2016 |

| Key Actors | Contest Setter | Subject Actors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil Palm Company | Small Plantation Company | Local Landowner | Permanent Employee | Freelance Day Laborer |

| Illegal Logging (0.546) | Illegal Logging (0.336) | Illegal Logging (0.151) | Illegal Logging (0.324) | Illegal Logging (0.142) |

| Clearing New Land (0.614) | Clearing New Land (0.762) | Clearing New Land (0.772) | Clearing New Land (0.600) | Clearing New Land (0.441) |

| Unsustainable Logging (0.275) | Unsustainable Logging (0.681) | Unsustainable Logging (0.536) | Unsustainable Logging (0.304) | Unsustainable Logging (0.167) |

| Land Conversion (0.415) | Land Conversion (0.741) | Land Conversion (0.853) | Land Conversion (0.528) | Land Conversion (0.365) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Purnomo, E.P.; Zahra, A.A.; Malawani, A.D.; Anand, P. The Kalimantan Forest Fires: An Actor Analysis Based on Supreme Court Documents in Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042342

Purnomo EP, Zahra AA, Malawani AD, Anand P. The Kalimantan Forest Fires: An Actor Analysis Based on Supreme Court Documents in Indonesia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042342

Chicago/Turabian StylePurnomo, Eko Priyo, Abitassha Az Zahra, Ajree Ducol Malawani, and Prathivadi Anand. 2021. "The Kalimantan Forest Fires: An Actor Analysis Based on Supreme Court Documents in Indonesia" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042342

APA StylePurnomo, E. P., Zahra, A. A., Malawani, A. D., & Anand, P. (2021). The Kalimantan Forest Fires: An Actor Analysis Based on Supreme Court Documents in Indonesia. Sustainability, 13(4), 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042342