Deep Learning-Based Knowledge Graph Generation for COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Pre-Trained Language Model

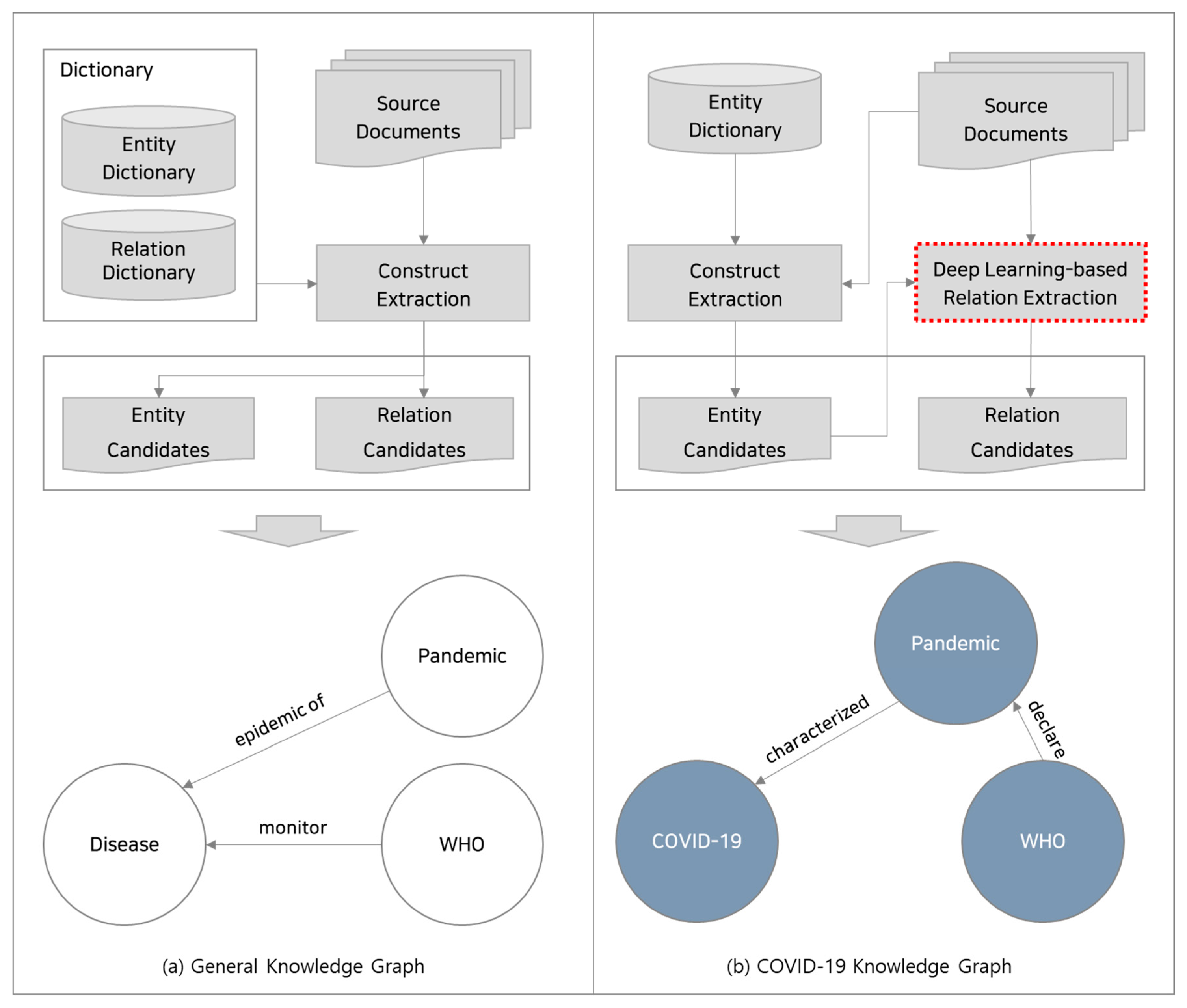

2.2. Knowledge Graph (KG)

2.3. Pre-Trained Language Model-Based KG

2.4. Open Information Extraction (OpenIE)

3. Proposed Methodology

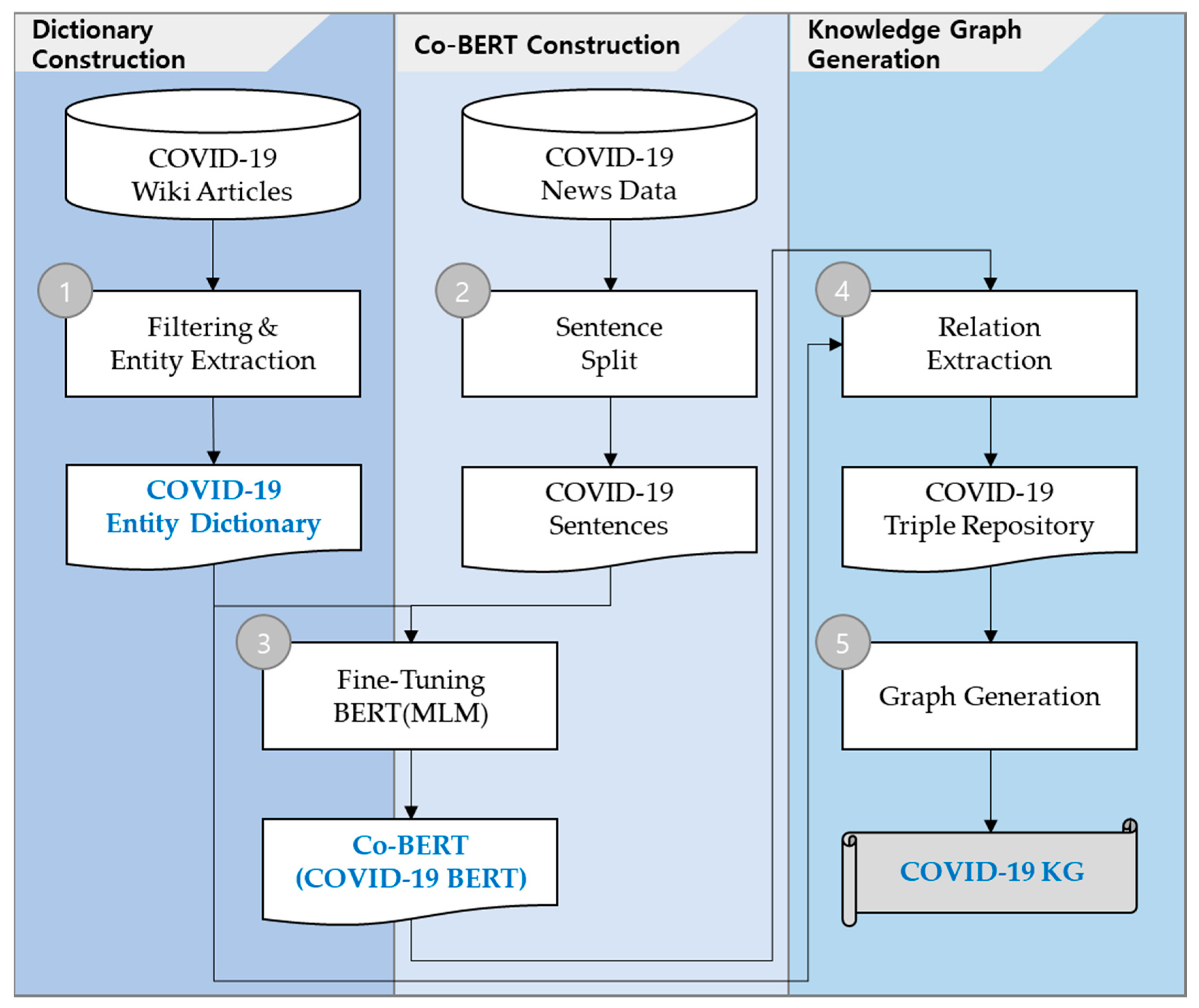

3.1. Research Process

3.2. COVID-19 Dictionary Construction

3.3. Co-BERT Construction

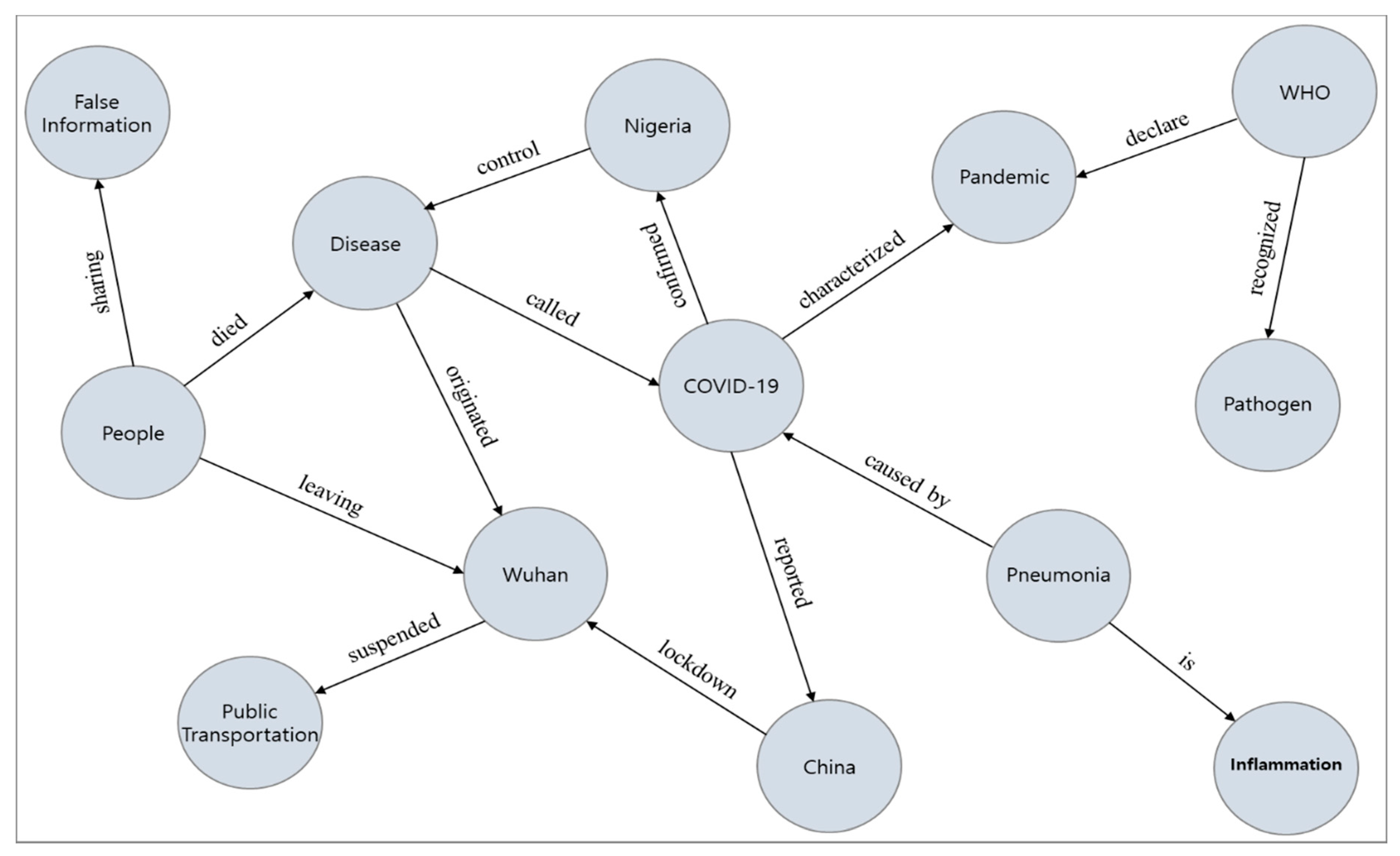

3.4. COVID-19-Based Knowledge Generation

4. Experiment

4.1. Overall

4.2. Constructing the COVID-19 Dictionary

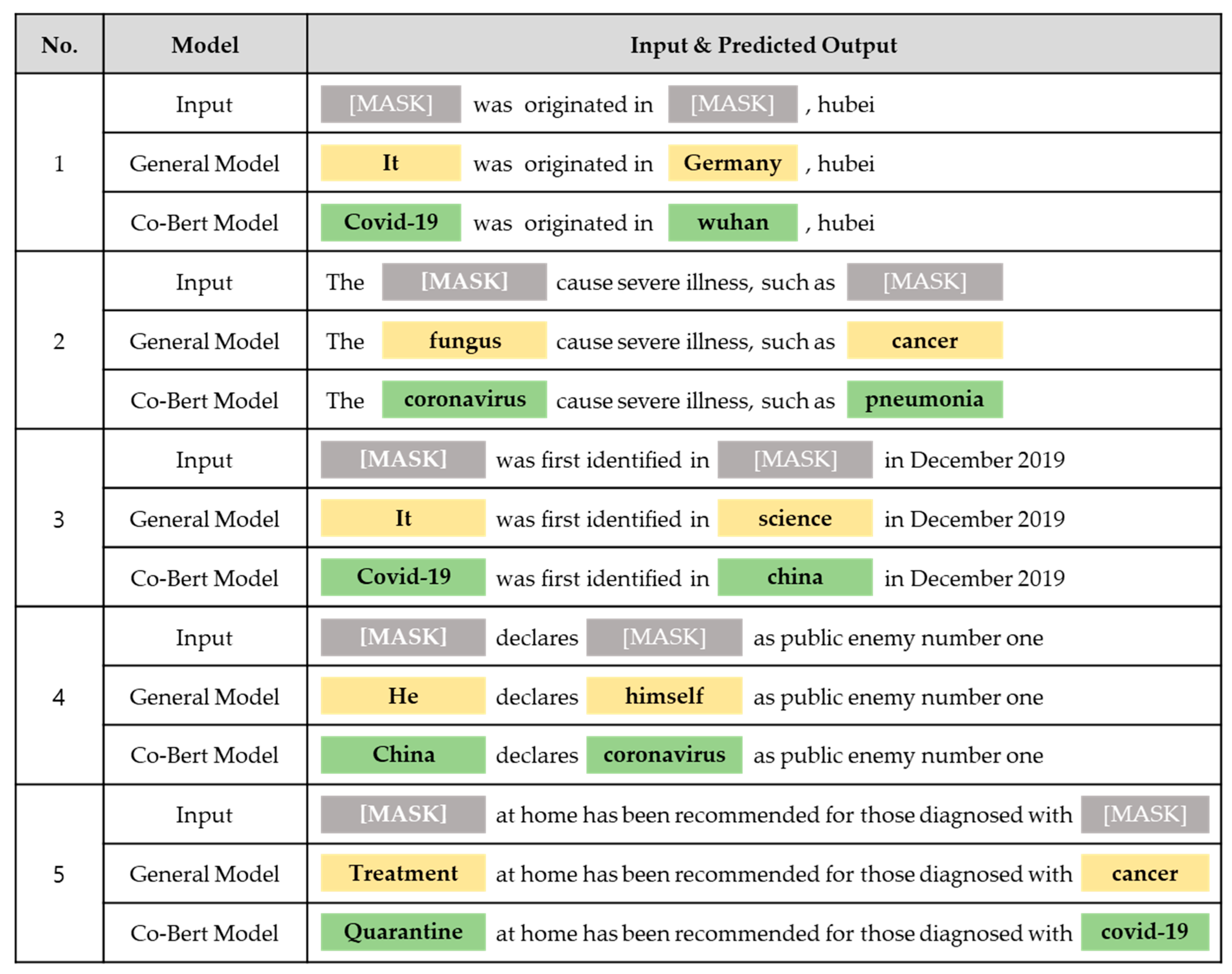

4.3. Constructing Co-BERT

4.4. Generating COVID-19-Based Knowledge

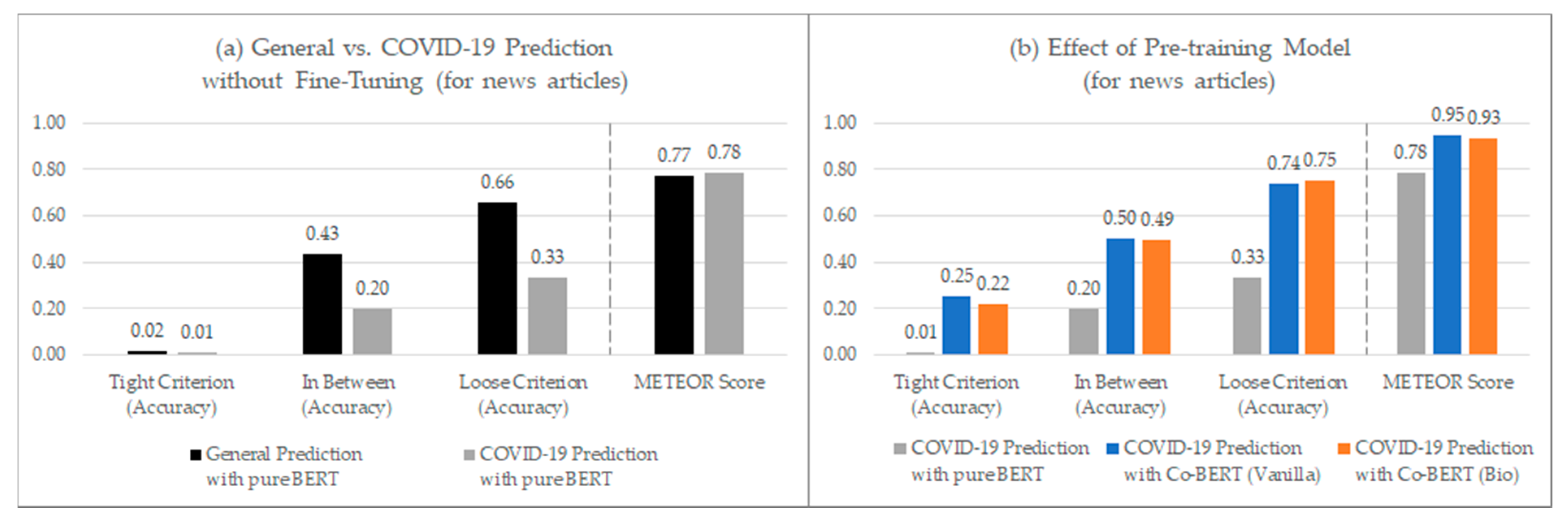

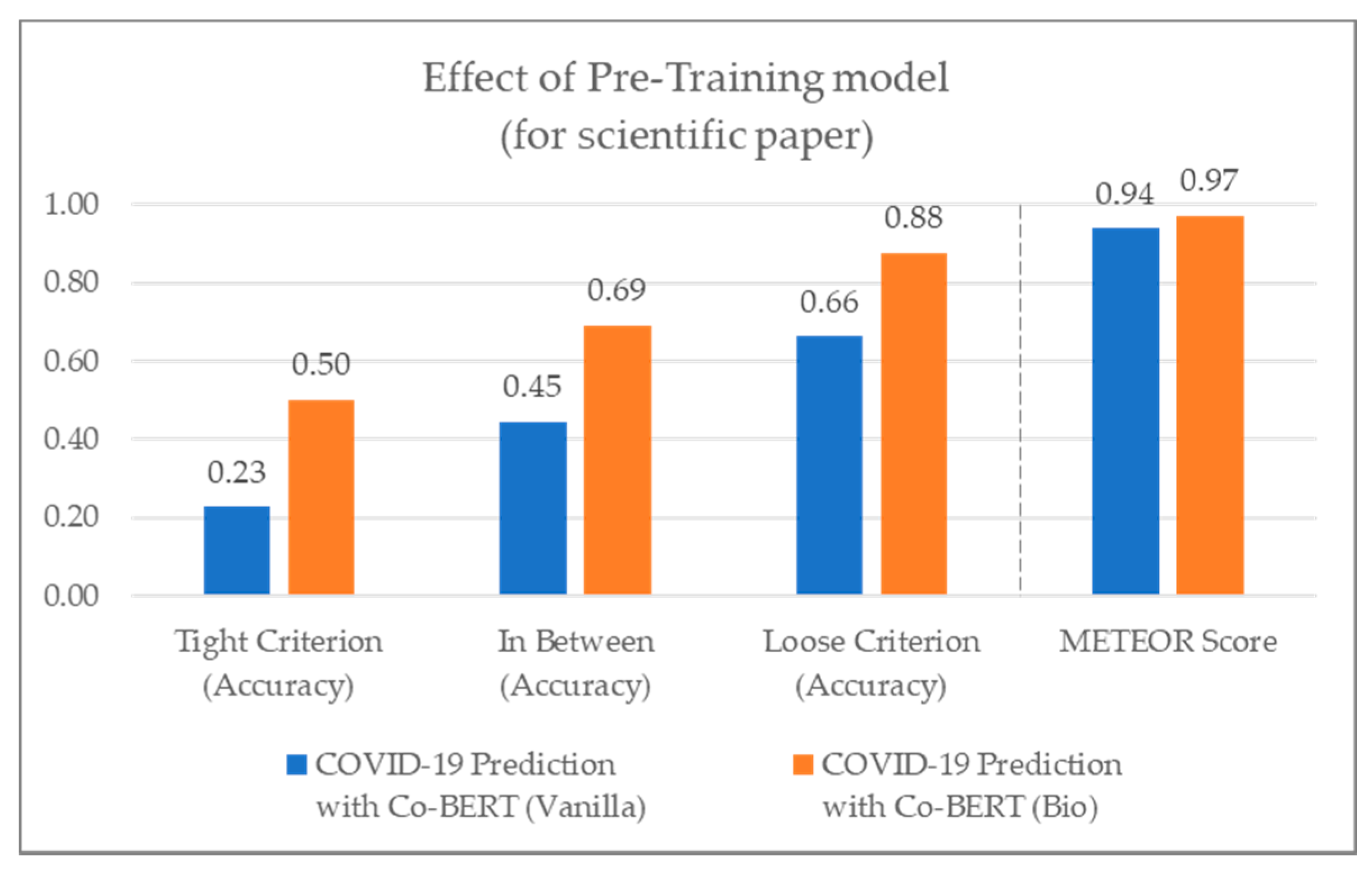

4.5. Evaluation

Co-BERT

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Edward, W.S. Course Modularization Applied: The Interface System and Its Implications for Sequence Control and Data Analysis; Association for the Development of Instructional Systems (ADIS): Chicago, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Google Official Blog. Introducing the Knowledge Graph: Things, Not Strings. Available online: https://blog.google/products/search/introducing-knowledge-graph-things-not (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Peters, M.E.; Neumann, M.; Iyyer, M.; Gardner, M.; Clark, C.; Lee, K.; Zettlemoyer, L. Deep Contextualized Word Representations. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.05365. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Le, Q.V. XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 5753–5763. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14165. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J. Pretraining-Based Natural Language Generation for Text Summarization. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.09243. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Xie, Y.; Tan, L.; Xiong, K.; Li, M.; Lin, J. Data Augmentation for BERT Fine-Tuning in Open-Domain Question Answering. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.06652. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, A.; Ram, A.; Tang, R.; Lin, J. DocBERT: BERT for Document Classification. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.08398. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.C.; Gan, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, J. Distilling Knowledge Learned in BERT for Text Generation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.03829. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Xia, Y.; Wu, L.; He, D.; Qin, T.; Zhou, W.; Li, H.; Liu, T.-Y. Incorporating BERT into Neural Machine Translation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.06823. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmy, L.; Xiang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Tao, C.; Zhi, D. Med-BERT: Pre-Trained Contextualized Embeddings on Large-Scale Structured Electronic Health Records for Disease Prediction. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.12833. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazvininejad, M.; Levy, O.; Liu, Y.; Zettlemoyer, L. Mask-Predict: Parallel Decoding of Conditional Masked Language Models. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09324. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.; Tan, X.; Qin, T.; Lu, J.; Liu, T.-Y. MASS: Masked Sequence to Sequence Pre-training for Language Generation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.02450. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, T.; Zang, L.; Han, J.; Hu, S. “Mask and Infill”: Applying Masked Language Model to Sentiment Transfer. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08039. [Google Scholar]

- Weizenbaum, J. ELIAZ—A Computer Program for the Study of Natural Language Communication between Man and Machine, Computational. Linguistics 1966, 9, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Csaky, R. Deep Learning Based Chatbot Models. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08835. [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Mlouk, A.; Jiang, L. Kbot: A Knowledge Graph Based ChatBot for Natural Language Understanding over Linked Data. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 149220–149230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondylakis, H.; Tsirigotakis, D.; Fragkiadakis, G.; Panteri, E.; Papadakis, A.; Fragkakis, A.; Tzagkarakis, E.; Rallis, I.; Saridakis, Z.; Trampas, A.; et al. R2D2: A Dbpedia Chatbot Using Triple-Pattern Like Queries. Algorithms 2020, 13, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, H. Knowledge Based High-Frequency Question Answering in Alime Chat. In Proceedings of the 18th International Semantic Web Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 26–30 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, A.V.D.; Imanuel, T.D.; Calista, M.I.; Nindito, H.; Condrobimo, A.R. The Application of AGNES Algorithm to Optimize Knowledge Base for Tourism Chatbot. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Information Management and Technology, Jakarta, Indonesia, 3–5 September 2018; pp. 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Belfin, R.V.; Shobana, A.J.; Megha, M.; Mathew, A.A.; Babu, B. A Graph Based Chatbot for Cancer Patients. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th Conference on Advanced Computing & Communication Systems, Tamil Nadu, India, 15–16 March 2019; pp. 717–721. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, L.; Luo, W.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, D. A Knowledge Graph Based Health Assistant. In Proceedings of the AI for Social Good Workshop at Neural IPS, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Divya, S.; Indumathi, V.; Ishwarya, S.; Priyasankari, M.; Devi, S.K. A Self-Diagnosis Medical Chatbot Using Artificial Intelligence. J. Web Dev. Web Des. 2018, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Q.; Ni, L.; Liu, J. HHH: An Online Medical Chatbot System based on Knowledge Graph and Hierarchical Bi-Directional Attention. In Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Science Week 2020, Melbourne, Australia, 4–6 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, C.; Power, R.; Callan, J. Explicit Semantic Ranking for Academic Search via Knowledge Graph Embedding. In Proceedings of the 2017 International World Wide Web Conference, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 1271–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Yan, Y.; Wang, J.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X. AceKG: A Lagre-scale Knowledge Graph for Academic Data Mining. In Proceedings of the Conference on Information and Knowledge Manangement 2018, Torino, Italy, 22–26 October 2018; pp. 1487–1490. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; He, X.; Cao, Y.; Liu, M.; Chua, T.-S. KGAT: Knowledge Graph Attention Network for Recommendation. In Proceedings of the Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 2019, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 950–958. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, M.; Li, W.; Xie, X.; Guo, M. Multi-Task Feature Learning for Knowledge Graph Enhanced Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 2000–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, F.; Wang, J.; Zhao, M.; Li, W.; Xie, X.; Guo, M. RippleNet: Propagating User Preferences on the Knowledge Graph for Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the Conference on Information and Knowledge Manangement 2018, Torino, Italy, 22–26 October 2018; pp. 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, K.M.; Krishnamurthy, M.; Alobaidi, M.; Hussain, M.; Alam, F.; Malik, G. Automated Domain-Specific Healthcare Knowledge Graph Curation Framework: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage as Phenotype. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 145, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmensch, M.; Halpern, Y.; Tlimat, A.; Horng, S.; Sontag, D. Learning a Health Knowledge Graph from Electronic Medical Records. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Lu, Y.; Zheng, V.W.; Chen, X.; Yang, B. KnowEdu: A System to Construct Knowledge Graph for Education. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 31553–31563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lv, Q.; Lan, X.; Zhang, Y. Cross-Lingual Knowledge Graph Alignment via Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018; pp. 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Tchechmedjiev, A.; Fafalios, P.; Boland, K.; Gasquet, M.; Zloch, M.; Zapilko, B.; Dietze, S.; Todorov, K. ClaimsKG: A Knowledge Graph of Fact-Checked Claims. In Proceedings of the 2109 18th International Semantic Web Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 26–30 October 2019; pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Feng, J.; Chen, Z. Knowledge Graph Embedding by Translating on Hyperplanes. In Proceedings of the 28th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Quebec, QC, Canada, 27–31 July 2014; pp. 1112–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, G.; He, S.; Xu, L.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J. Knowledge Graph Embedding via Dynamic Mapping Matrix. In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Beijing, China, 26–31 July 2015; pp. 687–696. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Tay, Y.; Yao, L.; Liu, Q. Quaternion Knowledge Graph Embeddings. In Proceedings of the 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, M.; Rosasco, L.; Poggio, T. Holographic Embeddings of Knowledge Graphs. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1510.04935. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, Y. Bootstrapping Entity Alignment with Knowledge Graph Embedding. In Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018; pp. 4396–4402. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Feng, J.; Chen, Z. Knowledge Graph and Text Jointly Embedding. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1591–1601. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Li, P. Knowledge Graph Embedding Based Question Answering. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Melbourne, Australia, 11–15 February 2019; pp. 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Bozzon, A.; Huang, L.K.; Xu, C. Recurrent Knowledge Graph Embedding for Effective Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM Conference on Recommeder System, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2–7 October 2018; pp. 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Dettmers, T.; Minervini, P.; Stenetorp, P.; Riedel, S. Convolutional 2D Knowledge Graph Embeddings. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.01476. [Google Scholar]

- Bouranoui, Z.; Camacho-Collados, J.; Schockaert, S. Inducing Relational Knowledge from BERT. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.12753. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, P.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ju, Q.; Deng, H.; Wang, P. K-BERT: Enabling Language Representation with Knowledge Graph. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.07606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Mao, C.; Luo, Y. KG-BERT: BERT for Knowledge Graph Completion. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.03193. [Google Scholar]

- Eberts, M.; Ulges, A. Span-based Joint Entity and Relation Extraction with Transformer Pre-training. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.07755. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, P.; Lin, J. Simple BERT Models for Relation Extraction and Semantic Role Labeling. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.05255. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Gao, T.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Tang, J. KEPLER: A Unified Model for Knowledge Embedding and Pre-trained Language Representation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.06136. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, S.; Jeong, O. Auto-Growing Knowledge Graph-based Intelligent Chatbot using BERT. ICIC Express Lett. 2020, 14, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ostendorff, M.; Bourgonje, P.; Berger, M.; Moreno-Schneider, J.; Rehm, G.; Gipp, B. Enriching BERT with Knowledge Graph Embeddings for Document Classification. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.08402. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Du, P.; Nie, J.Y. VGCN-BERT: Augmenting BERT with Graph Embedding for Text Classification. In Proceedings of the 42nd European Conference on Information Retrieval Research, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 April 2020; pp. 369–382. [Google Scholar]

- English Wikipedia, Open Information Extraction. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_information_extraction (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Etzioni, O. Search needs a shake-up. Nature 2011, 476, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fader, A.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Etzioni, O. Open question answering over curated and extracted knowledge bases. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’14), New York, NY, USA; pp. 1156–1165.

- Soderland, S.; Roof, B.; Qin, B.; Xu, S.; Etzioni, O. Adapting Open Information Extraction to Domain-Specific Relations; AI Magazine: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2010; Volume 31, pp. 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Banko, M.; Cafarella, M.J.; Soderland, S.; Broadhead, M.; Etzioni, O. Open Information Extraction from the Web. In Proceedings of the 20th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Hyderabad, India, 6–12 January 2007; pp. 2670–2676. [Google Scholar]

- Fader, A.; Soderland, S.; Etzioni, O. Identifying relations for open information extraction. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP ’11), Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, 27–31 July 2011; pp. 1535–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Angeli, G.; Premkumar, M.J.J.; Manning, C.D. Leveraging linguistic structure for open domain information extraction. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Beijing, China, 26–31 July 2015; pp. 344–354. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Seo, S.; Choi, Y.S. Semantic Relation Classification via Bidirectional Networks with Entity-Aware Attention Using Latent Entity Typing. Symmetry 2019, 11, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovsky, G.; Michael, J.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Dagan, I. Supervised Open Information Extraction. In Proceedings of the NAACL-HLT 2018, New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018; pp. 885–895. [Google Scholar]

- English Wikipedia, Potal: Coronavirus Disease 2019. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portal:Coronavirus_disease_2019 (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Clark, K.; Khandelwal, U.; Levy, O.; Manning, C.D. What Does BERT Look At? An Analysis of BERT’s Attention. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.04341. [Google Scholar]

- Jawahar, G.; Sagot, B.; Seddah, D. What does BERT Learn About the Structure of Language? In Proceedings of the ACL 2019—57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, A.; Kovaleva, O.; Rumshisky, A. A Primer in BERTology: What We Know About How BERT Works. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.12327. [Google Scholar]

- Kovaleva, O.; Romanov, A.; Rogers, A.; Rumshisky, A. Revealing the Dark Secrets of BERT. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08593. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, D.; Brunner, G.; Wattenhofer, R. Telling BERT’s full story: From Local Attention to Global Aggregation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.05916. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, J.Y.; Myaeng, S.H. Roles and Utilization of Attention Heads in Transformer-Based Neural Language Models. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Washington, DC, USA, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 3404–3417. [Google Scholar]

- Vig, J. A Multiscale Visualization of Attention in the Transformer Model. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.05714. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Z. Fine-tune BERT with Sparse Self-Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 3548–3553. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Parulian, N.; Han, G.; Ma, J.; Tu, J.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; et al. COVID-19 Literature Knowledge Graph Construction and Drug Repurposing Report Generation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.00576. [Google Scholar]

| Filter ID | Filters | Defined by | Filter ID | Filters | Defined by |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter 1 | COVID-19 pandemic ~ | Title | Filter 6 | Company | Category |

| Filter 2 | by ~ | Title | Filter 7 | Encoding Error | Contents |

| Filter 3 | Impact of ~ | Title | Filter 8 | President of ~ | Category |

| Filter 4 | list of ~ | Title | Filter 9 | lockdown in (place) | Title |

| Filter 5 | pandemic in (place) | Title | Filter 10 | External Link | Content |

| Version | Entity = 0 | Entity = 1 | Entity = 2 | Entity = 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Version1 | Excluded | Excluded | 2 Entities | Excluding |

| Version2 | Excluded | Excluded | 2 Entities | 2 Random Entities |

| Version3 | Excluded | 1 Random Token & 1 Entity | 2 Entities | 2 Random Entities |

| Version4 | 2 Random Tokens | 1 Random Token & 1 Entity | 2 Entities | 2 Random Entities |

| Covid-19 (Head Entity) | Wuhan (Tail Entity) | Covid-19 * Wuhan | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covid-19 | 11 | 4 | 44 |

| was | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| originated | 12 | 9 | 108 |

| in | 1 | 6 | 6 |

| Wuhan | 4 | 9 | 36 |

| Hubei | 2 | 15 | 30 |

| No. | Entities | No. | Entities | No. | Entities | No. | Entities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pandemic | 11 | Hand washing | 21 | Zoonosis | 31 | Herd immunity |

| 2 | Wuhan | 12 | Social distancing | 22 | Pangolin | 32 | Epidemic curve |

| 3 | Fatigue | 13 | Self-isolation | 23 | Guano | 33 | Semi log plot |

| 4 | Anosmia | 14 | COVID-19 testing | 24 | Wet market | 34 | Logarithmic scale |

| 5 | Pneumonia | 15 | Contact tracing | 25 | COVID-19 | 35 | Cardiovascular disease |

| 6 | Incubation period | 16 | Coronavirus recession | 26 | Septic Shock | 36 | Diabetes |

| 7 | COVID-19 vaccine | 17 | Great Depression | 27 | Gangelt | 37 | Nursing home |

| 8 | Symptomatic treatment | 18 | Panic buying | 28 | Blood donor | 38 | Elective surgery |

| 9 | Supportive therapy | 19 | Chinese people | 29 | Cohort study | 39 | Imperial College |

| 10 | Preventive healthcare | 20 | Disease cluster | 30 | Confidence interval | 40 | Neil Ferguson |

| No | Head Entity | Relation | Tail Entity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | People | died | Disease |

| 2 | Disease | called | COVID-19 |

| 3 | COVID-19 | confirmed | Nigeria |

| 4 | China | lockdown | Wuhan |

| 5 | Wuhan | suspended | Public Transportation |

| 6 | People | leaving | Wuhan |

| 7 | Pneumonia | caused by | COVID-19 |

| 8 | WHO | declare | Pandemic |

| 9 | COVID-19 | characterized | Pandemic |

| 10 | Pneumonia | is | Inflammation |

| 11 | People | sharing | False Information |

| 12 | Disease | originated | Wuhan |

| 13 | COVID-19 | reported | China |

| 14 | Nigeria | control | Disease |

| 15 | WHO | recognized | Pathogen |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, T.; Yun, Y.; Kim, N. Deep Learning-Based Knowledge Graph Generation for COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042276

Kim T, Yun Y, Kim N. Deep Learning-Based Knowledge Graph Generation for COVID-19. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042276

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Taejin, Yeoil Yun, and Namgyu Kim. 2021. "Deep Learning-Based Knowledge Graph Generation for COVID-19" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042276

APA StyleKim, T., Yun, Y., & Kim, N. (2021). Deep Learning-Based Knowledge Graph Generation for COVID-19. Sustainability, 13(4), 2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042276