Sustainability Assessment and Agricultural Supply Chains Evidence-Based Multidimensional Analyses as Tools for Strategic Decision-Making—The Case of the Pineapple Supply Chain in Benin

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Development Goals and Agenda

2.2. Sustainability Assessment

2.3. Agricultural Supply Chains Sustainability Assessment and Management

2.4. Guides and Frameworks for Supply Chains Development and Sustainability Strategies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Beninese Pineapple Short Supply Chain Context and Decision-Makers Strategies

3.2. The Value Chain Analysis for Development (VCA4D) Framework

4. Results and Interpretation

4.1. The VCA4D Method Applied to the Pineapple Supply Chain in Benin

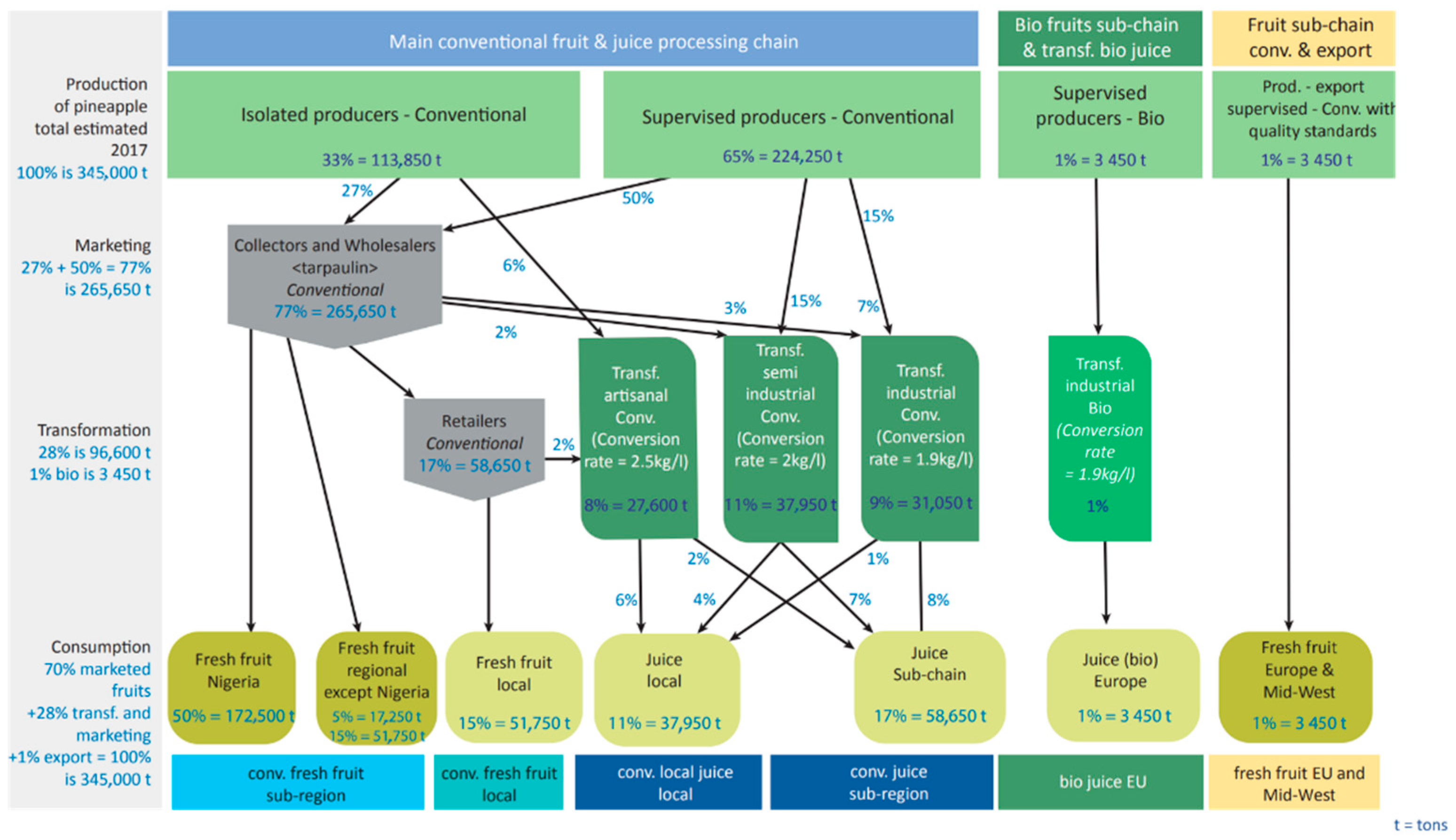

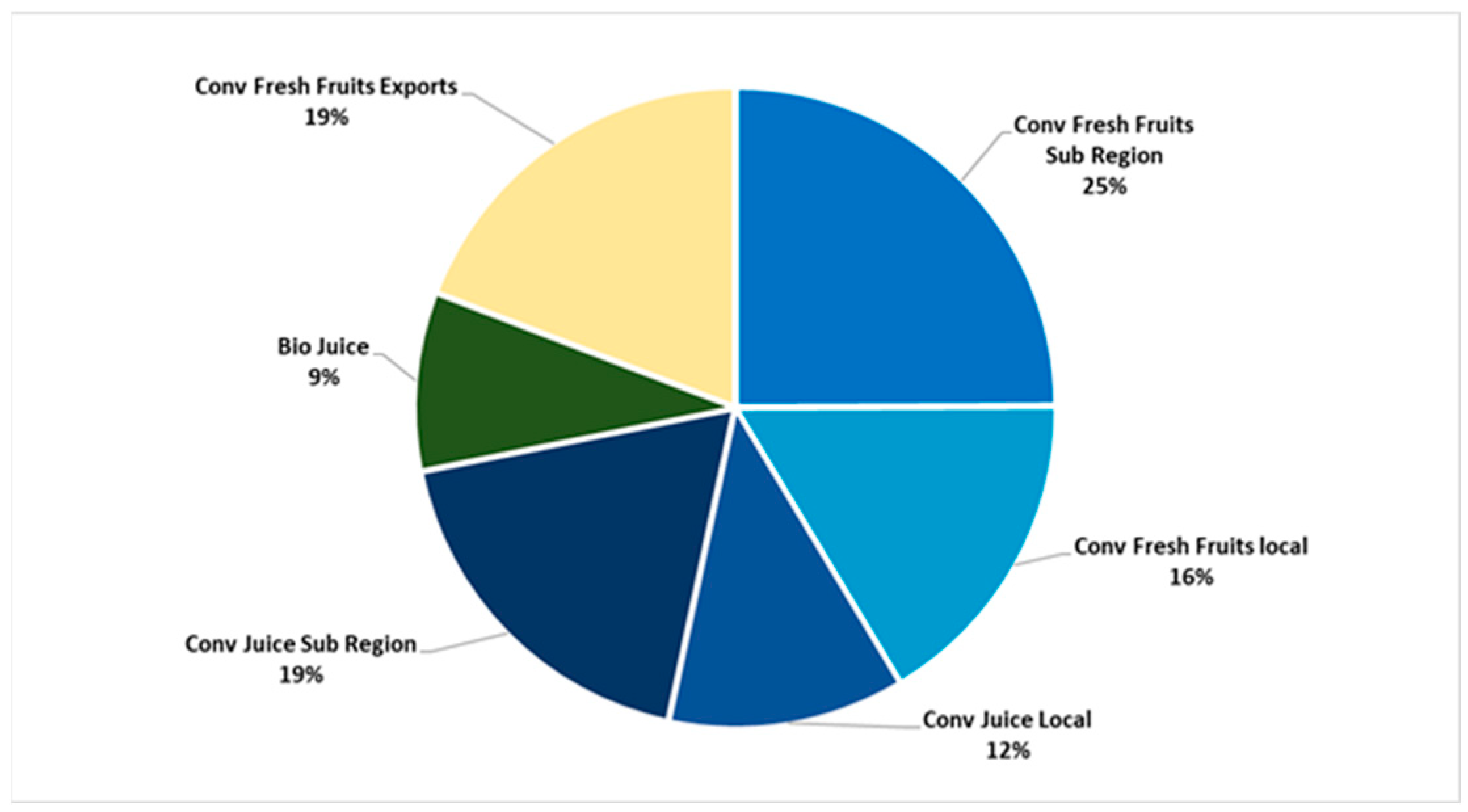

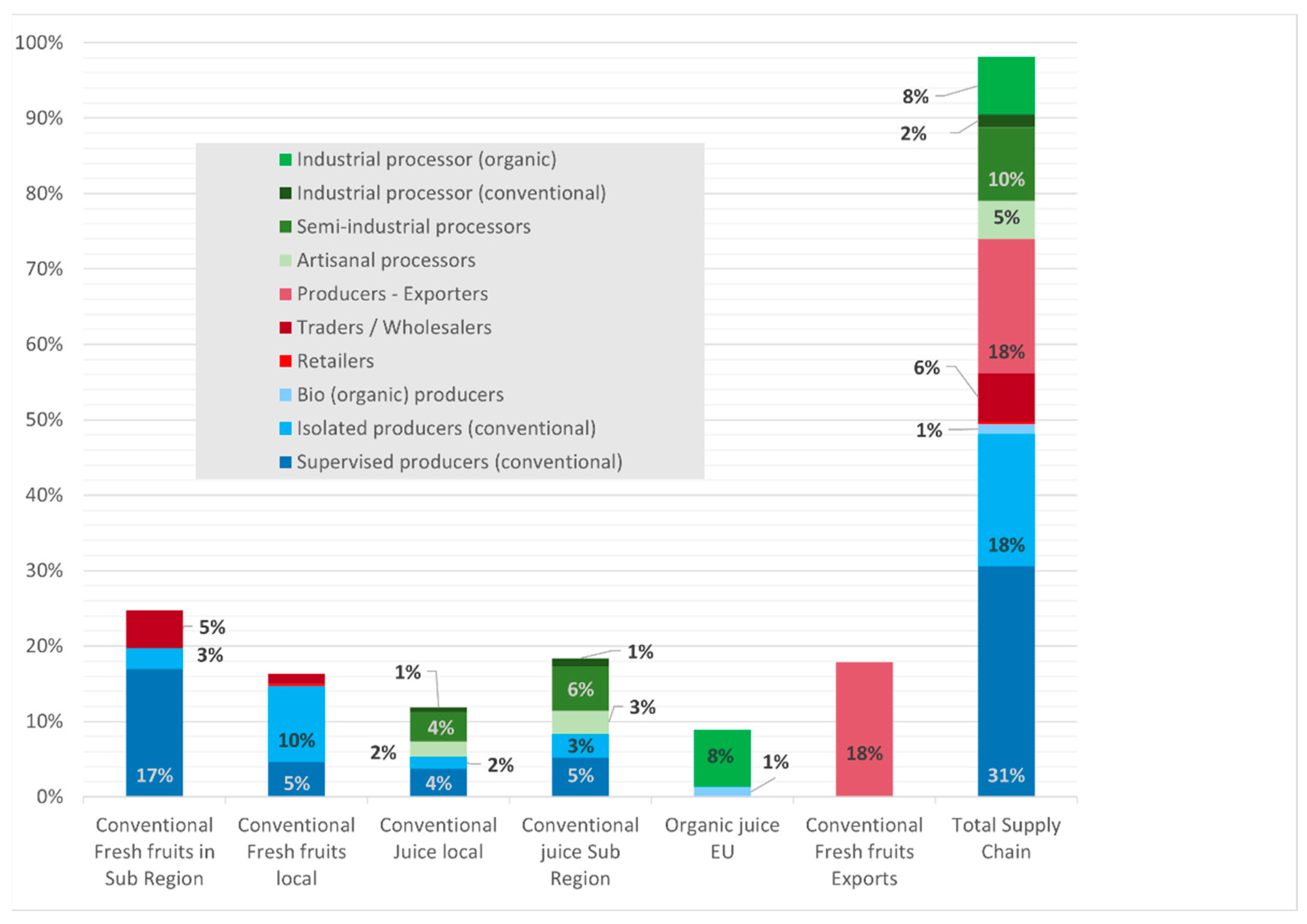

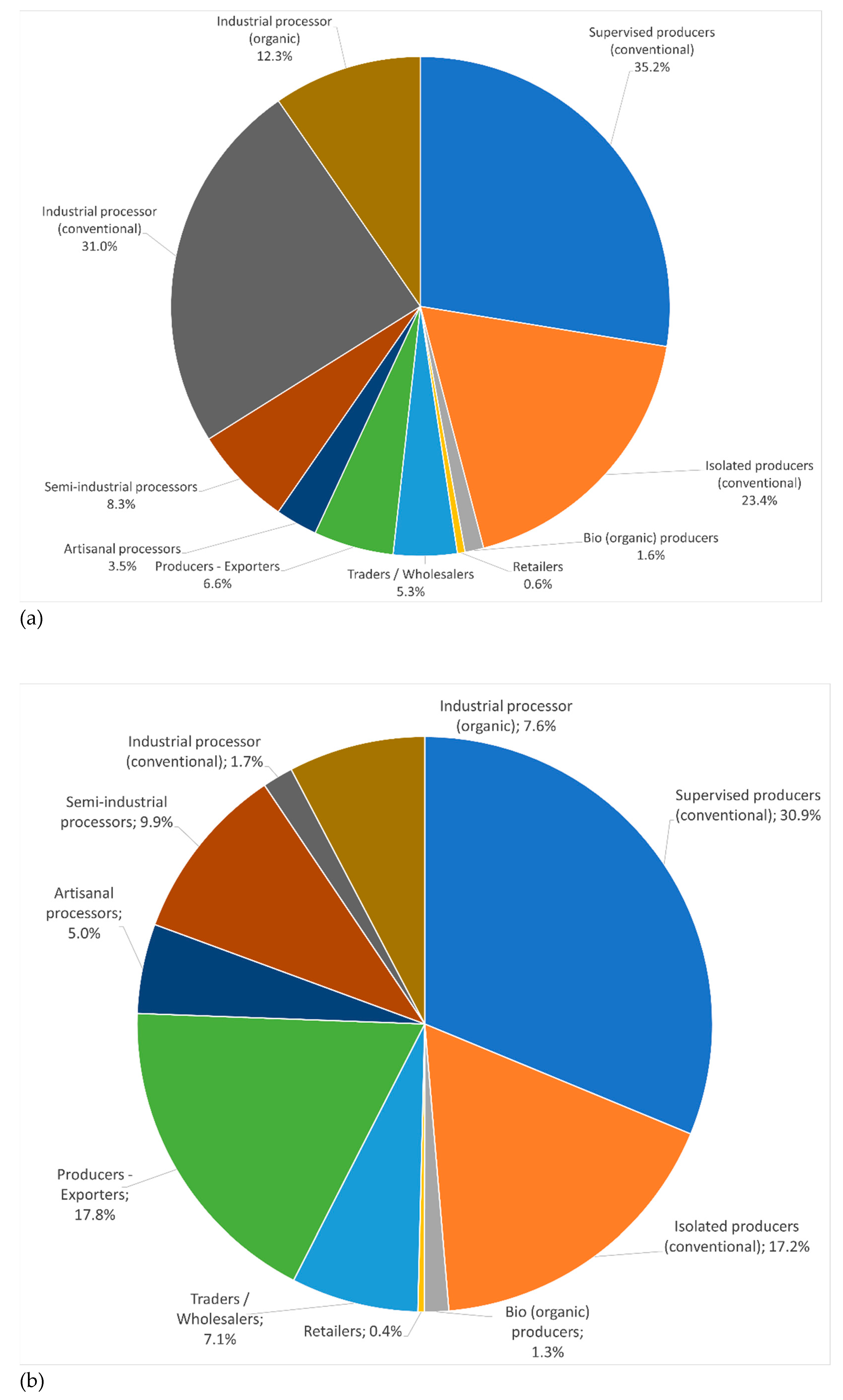

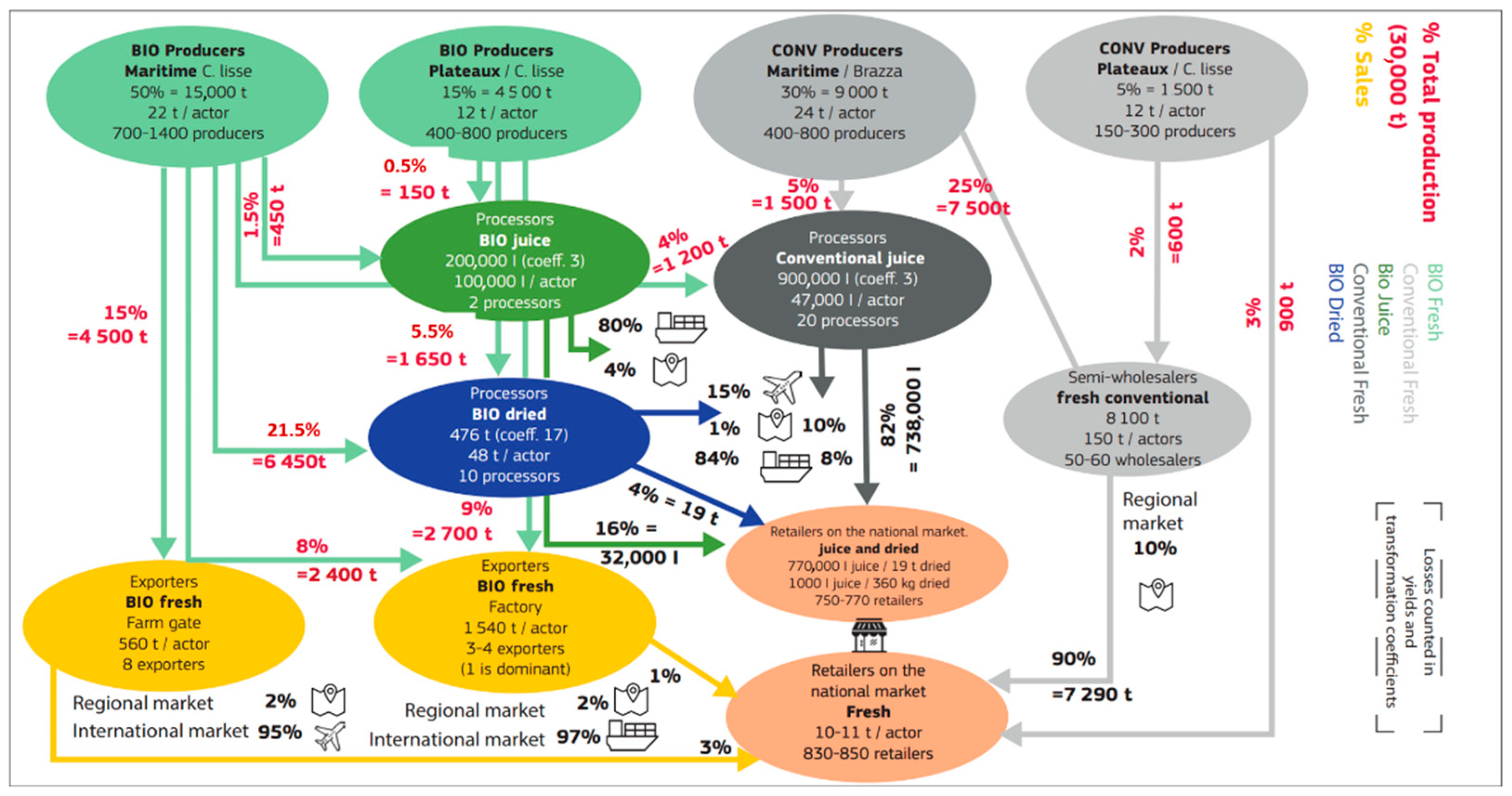

4.1.1. The Functional Analysis

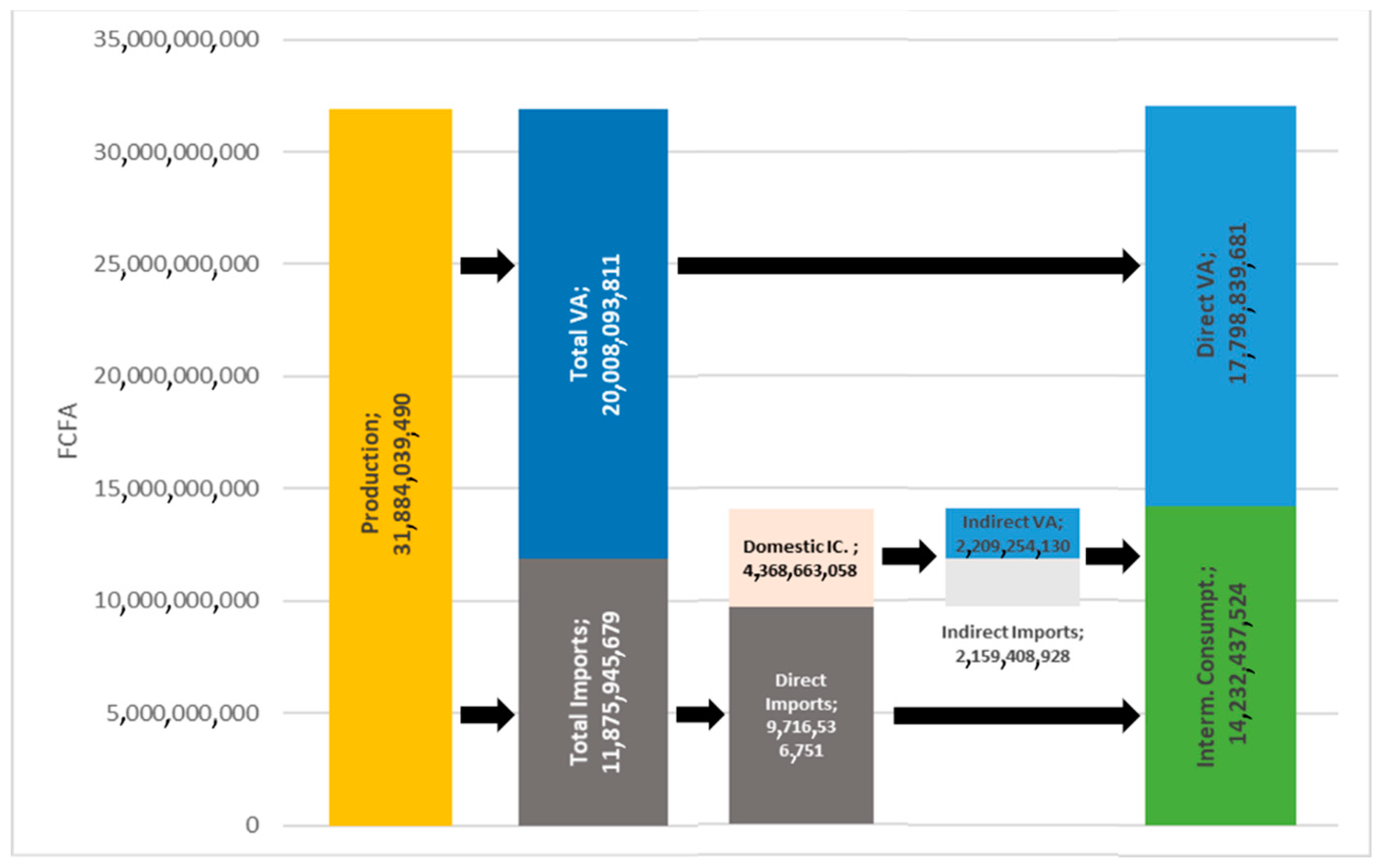

4.1.2. The Economic Analysis

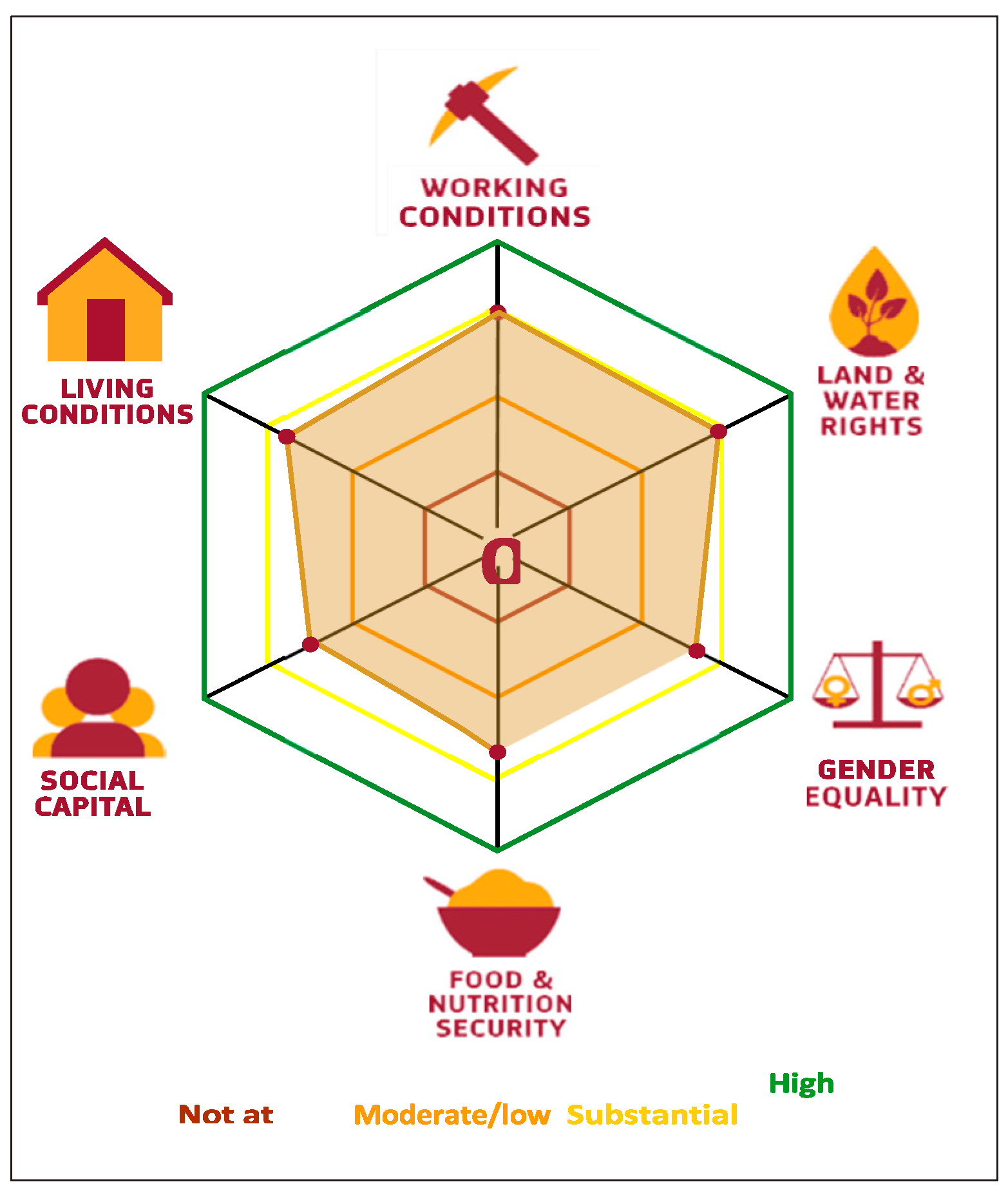

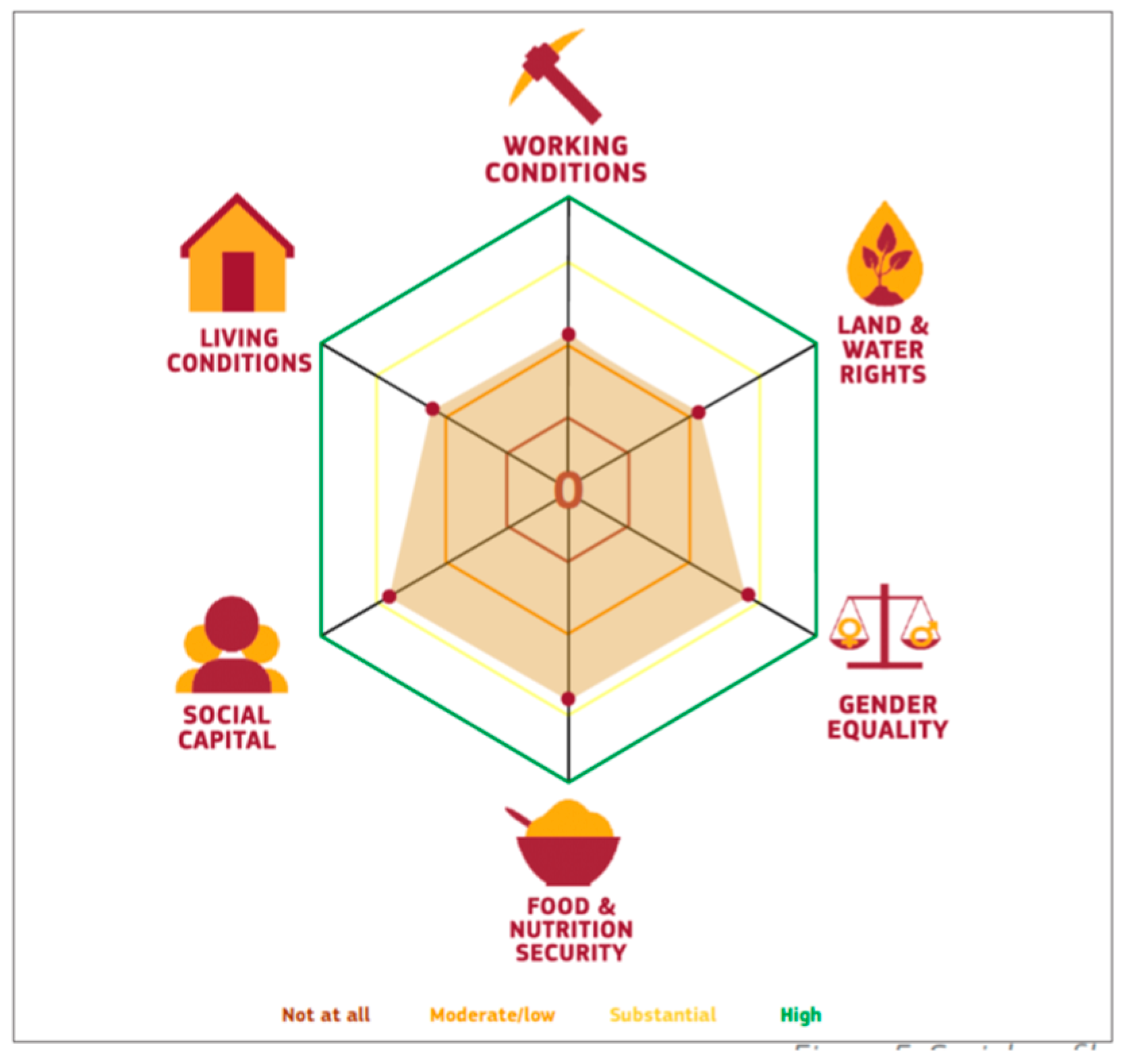

4.1.3. The Social Analysis

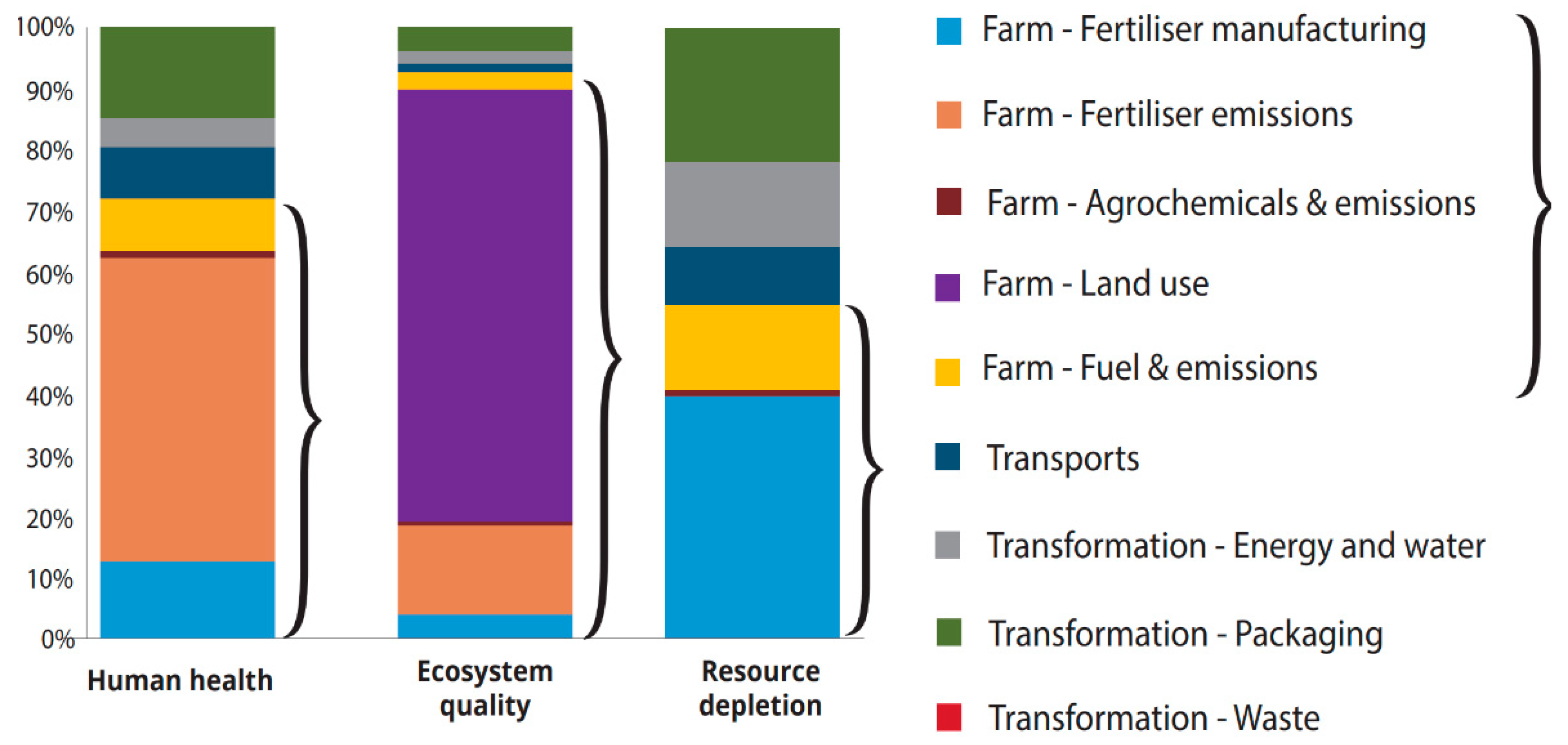

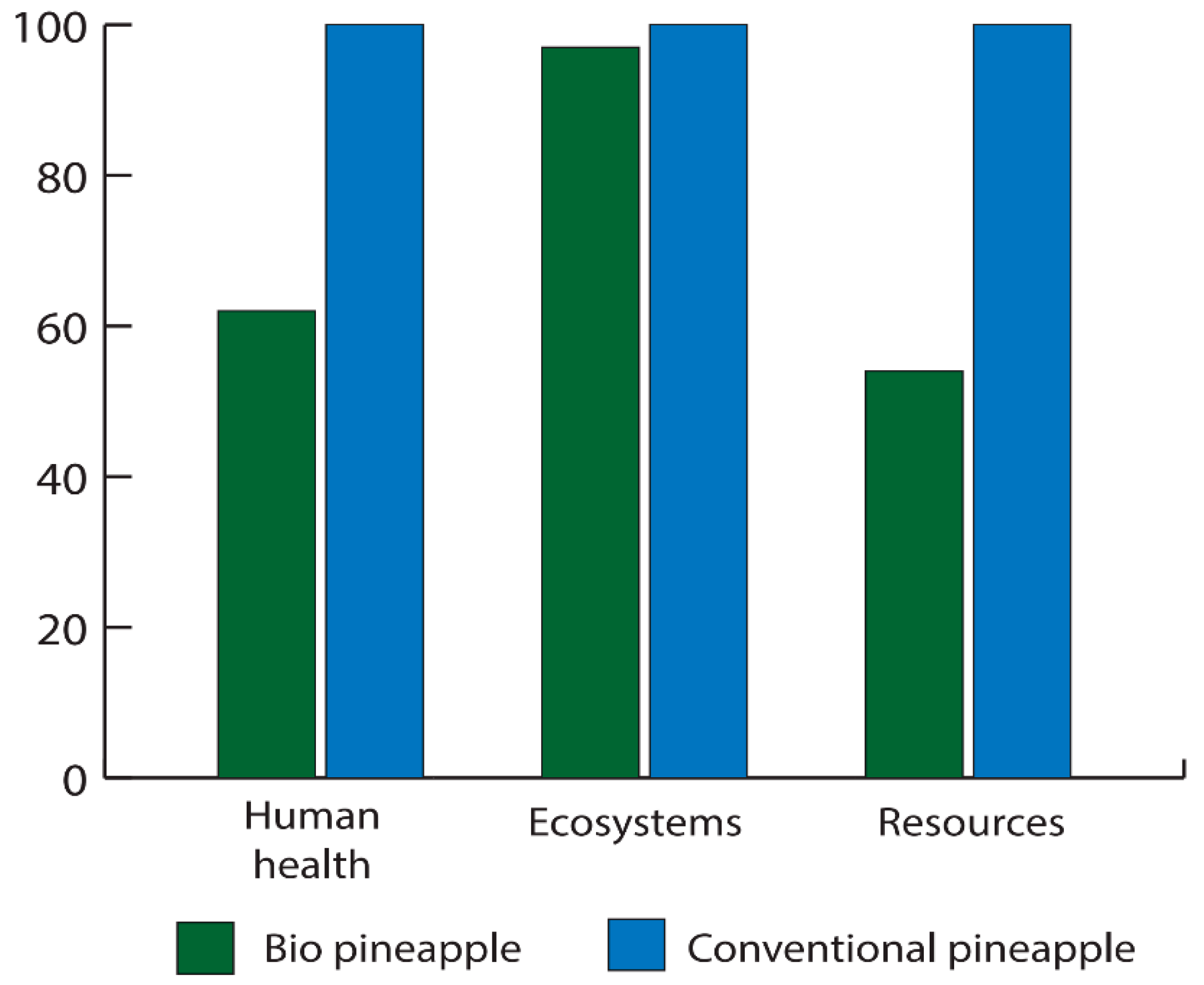

4.1.4. The Environmental Analysis

4.2. The VCA4D Method Applied to the Pineapple Supply Chain in Togo

4.2.1. The Functional Analysis

4.2.2. The Economic Analysis

4.2.3. The Social Analysis

4.2.4. The Environmental Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Limits of the VCA4D Method

5.2. Improvements Suggested for Further Supply Chains Sustainability Analyses

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leal Filho, W.; Tripathi, S.K.; Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.D.; Giné-Garriga, R.; Orlovic Lovren, V.; Willats, J. Using the sustainable development goals towards a better understanding of sustainability challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Mejía, M.; Franco-Garcia, M.-L.; Jauregui-Becker, J.M. Sustainability transitions in the developing world: Challenges of socio-technical transformations unfolding in contexts of poverty. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Flores, R.B.; Cruz-Sotelo, S.E.; Ojeda-Benitez, S.; Ramírez-Barreto, M.E. Sustainable Supply Chain Management—A Literature Review on Emerging Economies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroegindewey, R.; Hodbod, J. Resilience of Agricultural Value Chains in Developing Country Contexts: A Framework and Assessment Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmitt, E.; Keech, D.; Maye, D.; Barjolle, D.; Kirwan, J. Comparing the Sustainability of Local and Global Food Chains: A Case Study of Cheese Products in Switzerland and the UK. Sustainability 2016, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nangl’ole, E.M.; Mithofer, D.; Franzel, S. Review of Guidelines and Manuals for Value Chain Analysis for Agricultural and Forest Products; ICRAF Occasional Paper No. 17; World Agroforestry Center: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, J.; Franzel, S.; Cunha, M.; Gyau, A.; Mithofer, D. Guides for value chain development: A comparative review. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2015, 5, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENABEL. Programme de Coopération Bilatérale Bénino-Belge pour la Période 2019–2023; ENABEL: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ENABEL. Mission D’appui Conseil au Bénin pour la Définition des Orientations du Prochain Programme de Coopération entre la Belgique et le Bénin; ENABEL: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ATDA. Plan de Campagne 2019–2020 de la Filière Ananas; ATDA: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gouvernement du Bénin. Programme D’action du Gouvernement (2016–2021); Gouvernement du Bénin: Cotonou, Benin, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cosinus Conseils. Programme National de Développement de la Filière Ananas (PNDFA); Version Provisoire; Cosinus Conseils: Cotonou, Benin, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cosinus Conseils. Programme National de Développement de la Filière Ananas (PNDFA); Annexe 12 Rapport Diagnostic Détaillé; Cosinus Conseils: Cotonou, Benin, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère du Plan et du Développement (MPD). Plan National de Développement 2018–2025; MPD: Cotonou, Benin, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Value Chain Analysis for Development. Methodological Brief, V2.1; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Development—What Is There to Know and Why Should We Care? Available online: https://www.unssc.org/news-and-insights/blog/sustainable-development-what-there-know-and-why-should-we-care (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Dima, A.M. Mapping the Sustainable Development Goals Relationships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waas, T.; Hugé, J.; Block, T.; Wright, T.; Benitez-Capistros, F.; Verbruggen, A. Sustainability Assessment and Indicators: Tools in a Decision-Making Strategy for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5512–5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pintér, L.; Hardi, P.; Martinuzzi, A.; Hall, J. Bellagio STAMP: Principles for sustainability assessment and measurement. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 17, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, J.; Bond, A.J.; Hugé, J.; Morrison-Saunders, A. Reconceptualising Sustainability Assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 62, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huge, J.; Waas, T.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; Koedam, N.; Block, T. A discourse-analytical perspective on sustainability assessment: Interpreting sustainable development in practice. Sustain. Sci. 2013, 8, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, J.; Grace, W. Sustainability assessment in context: Issues of process, policy and governance. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2006, 8, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaie, H.; Fourcadet, O. Guidelines for Value Chain Analysis in the Agri-food Sector of Transitional and Developing Economies; ESSEC Business School France: Cergy, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Gawankar, S.A. Achieving sustainable performance in a data-driven agriculture supply chain: A review for research and applications. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 219, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, D.; Madzik, P.; Domingues, P. Development of Key Processes along the Supply Chain by Implementing the ISO 22000 Standard. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFDB. Document de Stratégie Pays 2017–2021; AFDB: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MAEP. Plan Stratégique de Développement du Secteur Agricole (PSDSA) 2025 et Plan National d’Investissements Agricoles et de Sécurité Alimentaire et Nutritionnelle PNIASAN 2017–2021; MAEP: Cotonou, Benin, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ahomadikpohou, D.L.; Vigninou, T.; N’Bessa, B. Production Agricole et Sécurité Alimentaire dans le Département de l’Atlantique au Sud du Bénin. Afr. Sci. Vol.11, N°6 (2015), 1 November 2015. Available online: http://www.afriquescience.info/document.php?id=5504. ISSN 1813-548X (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Kpenavoun Chogou, S.; Gandonou, E.; Fiogbe, N. Mesure de l’efficacité technique des petits producteurs d’ananas au Bénin. Cah. Agric. 2017, 26, 25004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cosinus Conseils. Etude de la Qualité du Jus D’ananas Béninois dans le Contexte de Marche Régional: Cas des Pays de L’hinterland (Burkina Faso, Niger) et de Nigeria, et Sénégal; Cosinus Conseils: Cotonou, Benin, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cosinus Conseils. Etude de la Qualité du Jus D’ananas Béninois dans le Contexte de Marche Régional: Cas des Pays de L’hinterland (Burkina Faso, Niger) et de Nigeria, et Sénégal; Cosinus Conseils: Cotonou, Benin, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cosinus Conseils. Etat des Lieux Sommaires des Pertes Post-Récolte au Niveau des Filières Tomate, Ananas et Pisciculture au Bénin; Cosinus Conseils: Cotonou, Benin, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Buck Consultant International. Agro-Logistics in Benin and Nigeria; Buck Consultant International: Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Financial and Economic Analysis of Development Projects; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1997; 420p, ISBN 92-827-9711-2. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. ISO 14040: 2006—Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. ISO 14044: 2006—Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dalberg et Growafrica. Etude des opportunités de marché pour la production commerciale de l’ananas au Bénin; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cosinus Conseils. Etude De Faisabilité Technique, Economique, Sociale Et Environnementale; Cosinus Conseils: Cotonou, Benin, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cosmos Consulting. Etude Des Circuits Economiques De La Filière Ananas; Cosmos Consulting: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kpenavoun Chogou, S.; Dohou, S.; Falade, H.; Hamidou, S.A.; Ichola, J. Recensement des Producteurs et des Unités de Transformation D’ananas au Bénin, pour le PROCAD et PADA; MAEP: Cotonou, Benin, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- MAEP. Recensement des Producteurs et des Unités de Transformation D’ananas au Bénin; MAEP: Cotonou, Benin, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- COLEACP. Itinéraire Technique pour L’ananas Pain de Sucre au Bénin; COLEACP: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MAEP. Analyse de la Performance des Chaînes de Valeurs de L’ananas au Bénin; MAEP: Cotonou, Benin, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- PNDFA. Etude de faisabilité technico-économique et socio- environnementale; Ministère de l’Agricuture: Cotonou, Benin, 2017.

- Sissinto Gbenou, E. Analyse de la Rentabilité Financière et Économique des Systèmes de Production de L’ananas au Benin. Ph.D. Thesis, Universite d’ Abomey Calavi, Godomey, Benin, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yabi, B.D. Analyse économique de la commercialisation de l’ananas au Bénin. Master’s Thesis, Universite d’ Abomey Calavi, Godomey, Benin, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Compétitivité de la Filière Ananas au Bénin; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Restitution FAO du Rapport sur la Compétitivité de la Filière Ananas au Benin; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Agoli-Agbo, M. Le Travail des 10–14 Ans au Bénin: Les Normes à L’épreuve des Faits; CEFORP-UAC: Cotonou, Benin, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- INSAE. Synthèse des Analyses sur les Caractéristiques Socioculturelles et Économiques de la Population; INSAE: Cotonou, Benin, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Synthèse des Analyses sur les Ménages; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- MAEP. Elaboration de la Situation de Référence sur les Conditions Actuelles d’Accès des Agricultrices/Agriculteurs à quatre Services Clés au Bénin; MAEP: Cotonou, Benin, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IBF International Consulting. Bénin Profil Genre 2017, Programme de l’Union Européenne pour le Développement; IBF International Consulting: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Programme Alimentaire Mondial. Analyse Globale de la Vulnérabilité et de la Sécurité Alimentaire (AGVSA); WFP: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- EMICCoV. Enquête Modulaire Intégrée sur les Conditions de Vie des Ménages; MDAEP: Cotonou, Benin, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- INSAE. Synthèse des Analyses sur L’état de la Structure de la Population; INSAE: Cotonou, Benin, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF-Benin. Analyse de la Situation des Enfants au Bénin; UNICEF: Cotonou, Benin, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Desclee, D.; Kinha, C.; Payen, S.; Sohinto, D.; Govindin, J.C. Analyse de la Chaîne de Valeur de L’ananas au Benin; Rapport pour l’Union Européenne, DG-DEVCO; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. VCA4D, N° 22, Pineapple Value Chain Analysis in Benin; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. VCA4D, N° 14, Pineapple value chain analysis in Togo; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Operations/Actors | Net Profit in Francs CFA | Value Added in Francs CFA | Total Net Profits Shares | Total Value-Added Shares |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised producers (Conv) | 3,575,293,997 | 5,493,916,750 | 35% | 31% |

| Isolated producers (Conv) | 2,380,004,363 | 3,062,059,629 | 23% | 17% |

| Collectors/wholesalers | 534,713,094 | 1,257,734,824 | 5% | 7% |

| Semi-industr. Processors | 837,577,711 | 1,753,936,846 | 8% | 10% |

| Retailers | 63,380,186 | 63,380,186 | 1% | 0% |

| Supervised producers (Bio) | 157,375,430 | 238,924,000 | 2% | 1% |

| Producers - exporters | 101,493,490 | 215,858,594 | 1% | 1% |

| Exporters | 671,025,000 | 3,174,000,000 | 7% | 18% |

| Artisanal processors | 351,588,739 | 885,897,126 | 3% | 5% |

| Industrial processor (Conv) | 257,555,457 | 302,120,191 | 3% | 2% |

| Industrial processor (Bio) | 1,221,906,543 | 1,351,011,535 | 12% | 8% |

| Overall Supply Chain | 10,151,914,009 | 17,798,839,681 | 100% | 100% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Desclee, D.; Sohinto, D.; Padonou, F. Sustainability Assessment and Agricultural Supply Chains Evidence-Based Multidimensional Analyses as Tools for Strategic Decision-Making—The Case of the Pineapple Supply Chain in Benin. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042060

Desclee D, Sohinto D, Padonou F. Sustainability Assessment and Agricultural Supply Chains Evidence-Based Multidimensional Analyses as Tools for Strategic Decision-Making—The Case of the Pineapple Supply Chain in Benin. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042060

Chicago/Turabian StyleDesclee, Doriane, David Sohinto, and Freddy Padonou. 2021. "Sustainability Assessment and Agricultural Supply Chains Evidence-Based Multidimensional Analyses as Tools for Strategic Decision-Making—The Case of the Pineapple Supply Chain in Benin" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042060