Rural Economic Development Based on Shift-Share Analysis in a Developing Country: A Case Study in Heilongjiang Province, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Method

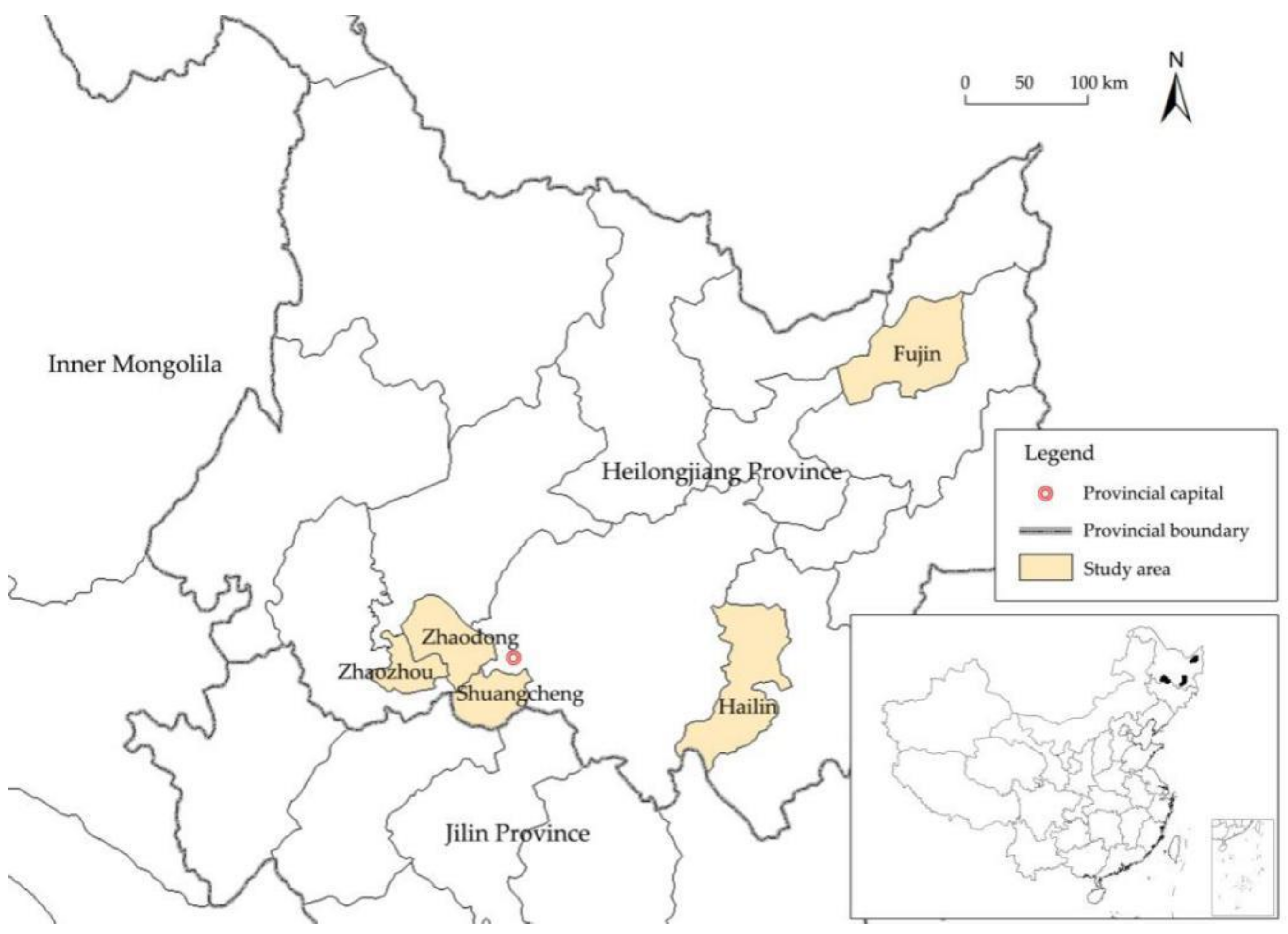

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Method

3.3. Data Sources

4. Results and Analysis

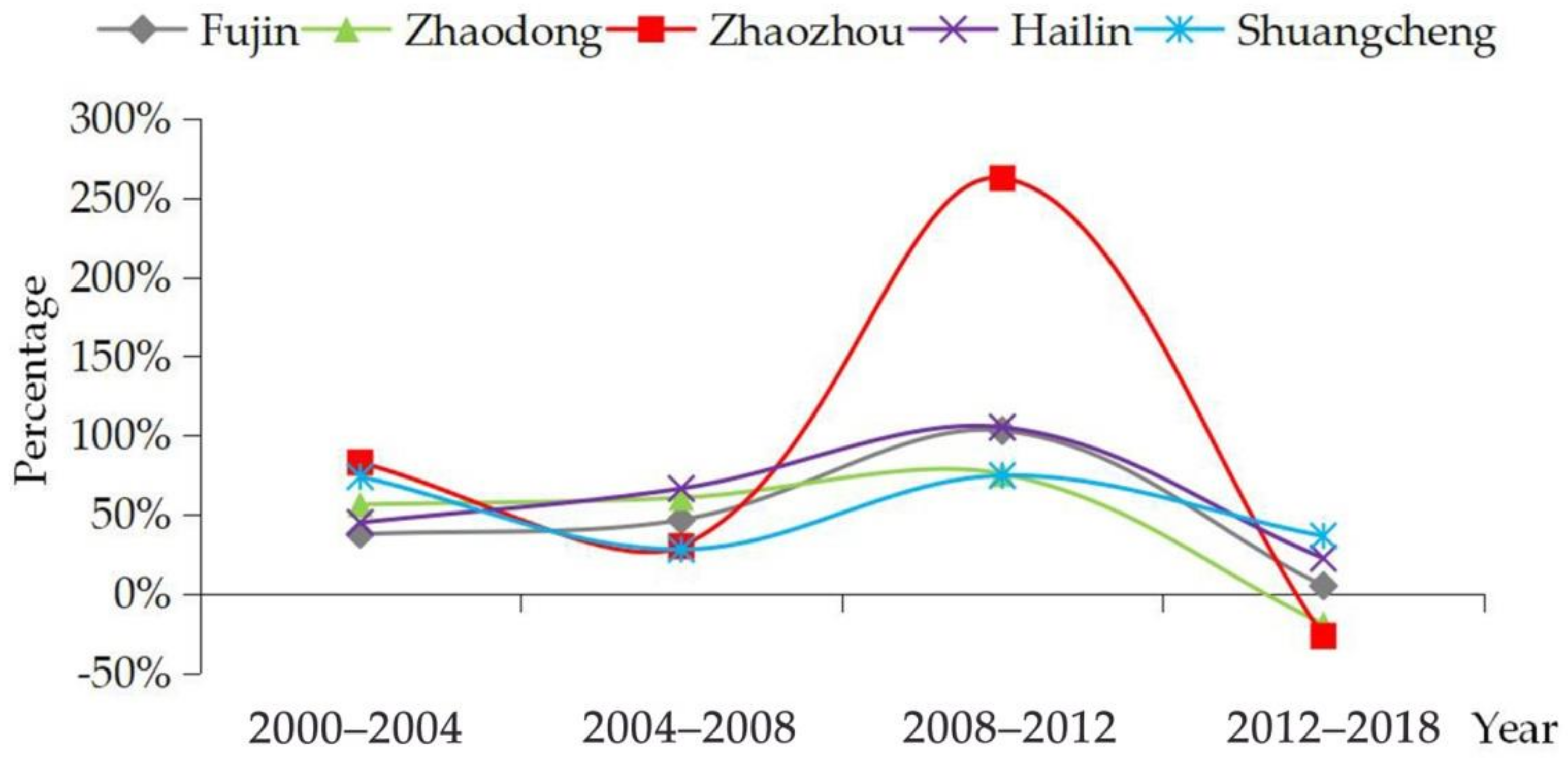

4.1. Decomposition of the Rural Economy Based on the Shift-Share Method

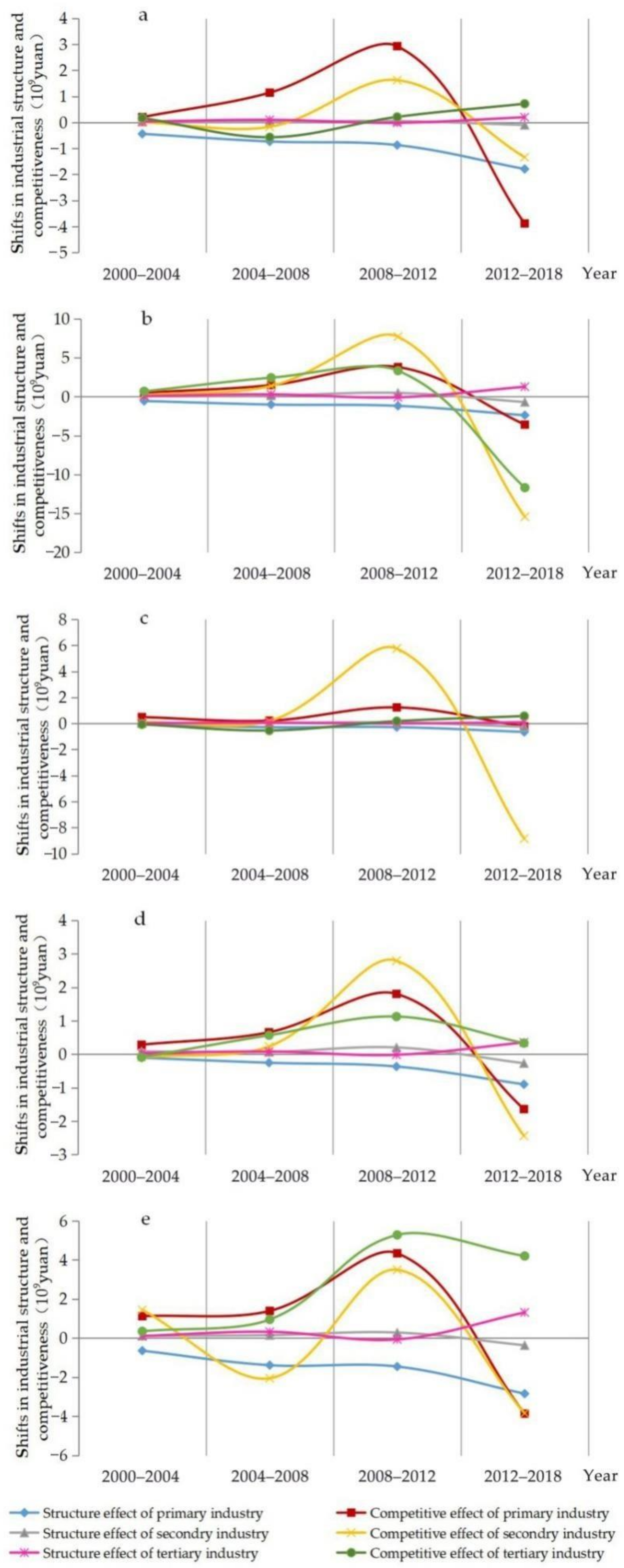

4.2. Shifts in Industrial Structure Share and Competitiveness Share

5. Discussion

- It is important for grain-producing counties such as Fujin to establish a diversified industrial structure, on the one hand, build a rational planting structure and increase corn, rice, soybeans, and other staple food production capacity; on the other hand, expand planting areas of economic and feed crops to meet the needs of diversified consumer demand. That is to say, market-oriented reform should be deepened to ensure the effective supply of agricultural products, especially for grain-producing counties. Additionally, the growth advantages of the tertiary industry should be fully utilized to extend the industrial chain; producer services with strong competitiveness will be supported, such as goods transportation, storage, and e-commerce services for high-quality agricultural products; and the non-agricultural population should be encouraged to engage in the business and logistics industry in connection with the green agricultural production system.

- Zhaodong county is famous for green agriculture and animal husbandry products. For this kind of county economy, the fiscal policy of the agricultural financial support system should be adjusted from being grain-oriented to having a focus on both grain and other high-value agricultural products, thus, it is feasible to construct a production and processing base for agricultural and sideline producing, and agricultural product trade, which will accelerate to form an industrial chain integrating planting (breeding), processing, and trade to improve the competitiveness of the county economy.

- Zhaozhou county should rely on local resources and industrial cluster advantages to explore enterprise transformation, such as food processing and technology-intensive industries (including biological organic fertilizer production and factory production of edible fungi). This is a feasible approach to deepening the division of labor and cooperation within neighboring regions, which may reduce corporations’ costs, improve regional production efficiency, and enhance regional competitiveness. This represents both an opportunity and a challenge for Zhaozhou to form new relationships between industry and agriculture, i.e., industry promoting agriculture or industry and agriculture benefitting each other.

- The leading role of ecotourism in regional economic growth is a promising approach for Hailin. The uniqueness of leisure agricultural products and services can be strengthened, and leisure agriculture management can be improved by exploring the potential of leisure agriculture in Hailin. New methods of media advertising, including web celebrities, and live broadcasts with goods should be encouraged to expand marketing strategies and increase the influence of leisure and sightseeing agriculture. Industrial integration can also be combined with landscape reconstruction, such as in the construction of a tourist town through population agglomeration, service agglomeration, spatial agglomeration, and ecological agglomeration, thus improving accessibility to services and rural public transport.

- The keys to development of urban–rural fringe areas such as Shuangcheng are to take advantage of location and logistics conditions, actively receive industrial transfer and urban economic radiation from Harbin, and construct industrial parks to attract a greater non-agricultural population. These areas can shift from a base of grain-production, dairy product processing, and food processing to a regional service center, such as in the form of a commercial center, logistics center, and service center. Investment, taxes, transfer payments, and other industrial support of local governments can focus reasonably on secondary and tertiary industries. Building large wholesale markets can also help to create jobs, develop agricultural tourism and ecological agriculture, and optimize the employment structure of surplus rural labor.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, H.; Luo, Q. Introduction to Regional Development of Agriculture; Beijing Science Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, J. Territorial types and optimization strategies of agriculture multifunctions: A case study of Jilin Province. Prog. Geogr. 2019, 38, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Regional differentiation and comprehensive regionalization scheme of modern agriculture in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.; Tu, S.; Ge, D.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. The allocation and management of critical resources in rural China under restructuring: Problems and prospects. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Analysis of evolutive characteristics and their driving mechanism of hollowing villages in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2009, 64, 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M. Rural Geography: Processes, Responses and Experiences in Rural Restructuring; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, P.J.; Kefalas, M.J. Hollowing out the Middle: The Rural Brain Drain and What It Means for America; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y. The cognition and path analysis of rural revitalization theory based on rural resilience. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2019, 74, 2001–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Voutilainen, O.; Wuori, O. Rural development within the context of agriculture and socio-economic trends: The case of Finland. Eur. Countrys. 2012, 4, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Priyanka, P.; Mulubrhan, A.; Thanh, T.N.; Christopher, B.B. Signalling change micro insights on the pathways to agricultural transformation. Int. Food Policy Res. Inst. 2019, 1, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Wu, W.H.; Liu, Y. The process of rural transformation in the world and prospects of sustainable development. Prog. Geo. 2018, 37, 627–635. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, J. Food security and the global agrifood system: Ethical issues in historical and sociological perspective. Glob. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perroux, F. Economic space, theory and applications. Q. J. Econ. 1950, 64, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Regional development policy: A case study of Venezuela. Urban Stud. 1967, 4, 309–311. [Google Scholar]

- Terluin, I.J. Differences in economic development in rural regions of advanced countries: An overview and critical analysis of theories. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.M.; Lichter, D.T. Rural depopulation: Growth and decline processes over the past century. Rural Sociol. 2019, 84, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Barrett, C.B. Agricultural industrialization, globalization, and international development: An overview of issues, patterns, and determinants. Agric. Econ. 2000, 23, 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, J. Policy implications of trends in agribusiness value chains. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2006, 18, 572–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, V. Re-figuring the problem of farmer agency in agrifood studies: A translation approach. J. Agric. Hum. Values 2006, 23, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhang, X. Progress in international rural geography research since the turn of the new millennium and some implications. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J. Impulses towards a multifunctional transition in rural Australia: Gaps in the research agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, A. Valuing the outputs of multifunctional agriculture. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2002, 29, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.L.; Marsden, T.; Miele, M.; Morley, A. Agricultural multifunctionality and farmers entrepreneurial skills: A study of Tuscan and Welsh farmers. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Renting, H.; Brunori, G.; Knickel, K.; Mannion, J.; Marsden, T.; De Roest, K.; Sevilla-Guzmán, E.; Ventura, F. Rural development: From practices and policies towards theory. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T. Mobilities, vulnerabilities and sustainabilities: Exploring pathways from denial to sustainable rural development. Sociol. Rural. 2009, 49, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, S.; Domon, G. Changing ruralities, changing landscapes: Exploring social recomposition using a multi-scale approach. J. Rural. Stud. 2003, 19, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G. From ‘weak’ to ‘strong’ multifunctionality: Conceptualising farm-level multifunctional transitional pathways. J. Rural. Stud. 2008, 24, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G. Multifunctional Agriculture: A transition Theory Perspective; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Granvik, M.; Lindberg, G.; Stigzelius, K.A.; Fahlbeck, E.; Surry, Y. Prospects of multifunctional agriculture as a facilitator of sustainable rural development: Swedish experience of Pillar 2 of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Nor. J. Geogr. 2012, 66, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Long, N.; Banks, J. Living Countryside. Rural Development Processes in Europe: The State of the Art; Elsevier: Doetinchem, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, G.; Salvia, R. An index to measure rural diversity in the light of rural resilience and rural development debate. Eur. Countrys. 2014, 6, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Atterton, J. Exploring the contribution of rural enterprises to local resilience. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 40, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuneke, P.; Lans, T.; Wiskerke, J.S.C. Moving beyond entrepreneurial skills: Key factors driving entrepreneurial learning in multifunctional agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.R. Distribution of landholdings in rural India, 1953–1954 to 1981–1982: Implications for land reforms. Econ. Political Wkly. 1994, 29, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Stola, W. The functional classification of rural areas in the mountain regions of Poland. Geogr. Pol. 1986, 52, 235–248. [Google Scholar]

- Linh, T.N.; Anh Tuan, D.; Thu Trang, P.; Trung Lai, H.; Do Anh, Q.; Viet Cuong, N.; Lebailly, P. Determinants of farming households’ credit accessibility in rural areas of Vietnam: A case study in Haiphong City, Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Xu, L.; You, H.; Hu, Y. The socio-economical zoning of the suburb hilly rural area in Beijing: A two-step cluster approach. Urban Stud. 2010, 7, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Liu, G. The demarcating of the rural economy type of Fujian province. J. Fujian Teach. Univ. 2002, 3, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, D.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, T. Farmland transition and its influences on grain production in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Nilsson, P.; Westlund, H. Demographic and economic trends in a rural Europe in transition. In Proceedings of the ERSA 2014—54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 26–29 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Polese, M.; Shearmur, R. Is distance really dead? Comparing location patterns over time in Canada. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2004, 27, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Comprehensive measure and partition of rural hollowing in China. Geogr. Res. 2012, 31, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar]

- Gollege, R.G. Sydney’s Metropolitan fringe: A study in urban-rural relations. Aust. Geogr. 1960, 7, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehand, J.W.R. Fringe belts: A neglected aspect of urban geography. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1967, 41, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Q. Discussion on land use mode in rural-urban fringe. China Land Sci. 1997, 11, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hoggart, K.; Paniagua, A. What rural restructuring. J. Rural. Stud. 2001, 17, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Tu, S. Rural restructuring: Theory, approach and research prospect. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 563–576. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Research overview of urban fringe domestic and overseas. Dev. Small Cities Towns 2019, 37, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Marquillas, J.M. A reinterpretation of shift-share analysis. Reg. Urban Econ. 1972, 2, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P.; Gardiner, B.; Tyler, P. How regions react to recessions: Resilience and the role of economic structure. Reg. Stud. 2016, 50, 561–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, P.; Guan, H.; Tan, J. Analysis of the regional economic resilience characteristics based on Shift-Share method in Liaoning old industrial base. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar]

- Khusaini, M. A shift-share analysis on regional competitiveness—A case of Banyuwangi district, East Java, Indonesia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goschin, Z. Regional growth in Romania after its accession to EU: A shift-share analysis approach. Econ. Financ. 2014, 15, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, X.; Pan, Y.; Hu, Y. Spatial features of agricultural growth by county from the perspective of industrial structure. J. Nat. Resour. 2018, 33, 246–261. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, H.; Zhang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J. A comparative analysis of the economic transition process of China’s old industrial cities based on evolutionary resilience theory. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 771–783. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.M.; Tian, W.M. Analysis of the contribution of rural labor transfer to economic growth in China. Manag. World 2005, 1, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.; Sun, D. Progress in urban shrinkage research. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 37, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, D.L.; Anderson, W.P. Employment change, growth and productivity in Canadian manufacturing: An extension and application of shift-share analysis. Can. J. Reg. Sci. 1993, 16, 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, K.; Dinc, M. Productivity change in manufacturing regions: A multifactor/shift-share approach. Growth Chang. 1997, 28, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrquez, M.A.; Ramajo, J.; Hewings, G.J.D. Incorporating sectoral structure into shift-share analysis. Growth Chang. 2009, 40, 594–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F. Has China’s labor mobility exhausted its momentum? Chin. Rural Econ. 2018, 9, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.L. The contribution of agricultural labor migration to economic growth in China. Econ. Res. J. 2016, 51, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

| County | 2000–2004 | 2004–2008 | 2008–2012 | 2012–2018 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔGDP | NGE | ISE | CE | ΔGDP | NGE | ISE | CE | ΔGDP | NGE | ISE | CE | ΔGDP | NGE | ISE | CE | |

| Fujin | ||||||||||||||||

| PI | 4.2 | 6.6 | −4.4 | 2.0 | 15.3 | 11.2 | −7.3 | 11.4 | 35.6 | 15.1 | −8.7 | 29.3 | −21.3 | 35.4 | −17.9 | −38.8 |

| SI | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 0.2 | −1.7 | 20.3 | 3.6 | 0.5 | 16.2 | 0 | 14.4 | −1.0 | −13.4 |

| TI | 5.4 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 7.7 | 1.0 | −5.7 | 9.0 | 7.1 | −0.1 | 2.1 | 21.9 | 12.8 | 2.0 | 7.1 |

| Zhaodong | ||||||||||||||||

| PI | 7.9 | 8.3 | −5.5 | 5.1 | 20.3 | 15.5 | −10.1 | 14.9 | 46.7 | 20.4 | −11.8 | 38.1 | −12.5 | 47.3 | −23.9 | −35.9 |

| SI | 15.2 | 11.4 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 39.1 | 23.8 | 1.5 | 13.8 | 116.9 | 34.8 | 4.9 | 77.2 | −62.1 | 99.2 | −6.9 | −154.4 |

| TI | 18.0 | 10.1 | 0.9 | 6.9 | 51.1 | 23.7 | 3.0 | 24.4 | 72.6 | 39.9 | −0.8 | 33.5 | −21.4 | 82.9 | 12.8 | −117.0 |

| Zhaozhou | ||||||||||||||||

| PI | 5.2 | 1.1 | −0.7 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 4.5 | −2.9 | 2.1 | 14.4 | 4.9 | −2.9 | 12.3 | 4.1 | 13.0 | −6.6 | −2.3 |

| SI | 2.8 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 63.5 | 5.3 | 0.7 | 57.5 | −53.2 | 38.0 | −2.6 | −88.6 |

| TI | 1.9 | 2.5 | 0.2 | −0.7 | −0.5 | 4.4 | 0.6 | −5.4 | 4.7 | 3.1 | −0.1 | 1.7 | 12.5 | 5.9 | 0.9 | 5.7 |

| Hailin | ||||||||||||||||

| PI | 3.3 | 1.6 | −1.1 | 2.8 | 7.9 | 4.0 | −2.6 | 6.5 | 20.7 | 6.4 | −3.7 | 18.0 | −7.6 | 17.8 | −9.0 | −16.4 |

| SI | 5.7 | 5.8 | 0.8 | −0.9 | 13.9 | 10.9 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 44.2 | 14.2 | 2.0 | 27.9 | 11.7 | 38.8 | −2.7 | −24.4 |

| TI | 2.9 | 3.5 | 0.3 | −0.9 | 12.8 | 6.3 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 21.3 | 10.3 | −0.2 | 11.2 | 29.4 | 22.7 | 3.5 | 3.3 |

| Shuang- cheng | ||||||||||||||||

| PI | 14.5 | 9.7 | −6.5 | 11.2 | 21.3 | 21.2 | −13.9 | 13.9 | 53.9 | 25.1 | −14.6 | 43.4 | −10.8 | 56.4 | −28.5 | −38.7 |

| SI | 23.4 | 7.9 | 1.1 | 14.4 | 4.9 | 24.0 | 1.5 | −20.6 | 57.9 | 20.1 | 2.8 | 34.9 | 10.4 | 52.6 | −3.7 | −38.5 |

| TI | 16.4 | 11.9 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 38.0 | 25.3 | 3.2 | 9.5 | 87.4 | 35.4 | −0.7 | 52.8 | 140.2 | 85.1 | 13.1 | 42.0 |

| County | 2000–2004 | 2004–2008 | 2008–2012 | 2012–2018 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔGDP | NGE | ISE | CE | ΔGDP | NGE | ISE | CE | ΔGDP | NGE | ISE | CE | ΔGDP | NGE | ISE | CE | |

| Fujin | 11.8 | 11.9 | −3.8 | 3.8 | 20.4 | 22.5 | −6.1 | 4.0 | 64.9 | 25.7 | −8.4 | 47.6 | 0.6 | 62.5 | −16.9 | −45.1 |

| Zhaodong | 41.0 | 29.8 | −3.0 | 14.2 | 110.5 | 63.1 | −5.7 | 53.1 | 236.2 | 95.1 | −7.8 | 148.9 | −96.0 | 229.4 | −18.0 | −307.3 |

| Zhaozhou | 10.0 | 5.2 | −0.3 | 5.1 | 8.9 | 12.6 | −2.1 | −1.6 | 82.6 | 13.3 | −2.2 | 71.5 | −36.5 | 56.9 | −8.3 | −85.2 |

| Hailin | 11.9 | 10.9 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 34.6 | 21.3 | −1.1 | 14.4 | 86.2 | 30.9 | −1.9 | 57.2 | 33.5 | 79.3 | −8.2 | −37.6 |

| Shuang- cheng | 54.3 | 29.6 | −4.3 | 29 | 64.1 | 70.5 | −9.2 | 2.8 | 199.3 | 80.6 | −12.5 | 131.1 | 139.9 | 194 | −19.0 | −35.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, D.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Y. Rural Economic Development Based on Shift-Share Analysis in a Developing Country: A Case Study in Heilongjiang Province, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041969

Lv D, Gao H, Zhang Y. Rural Economic Development Based on Shift-Share Analysis in a Developing Country: A Case Study in Heilongjiang Province, China. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041969

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Donghui, Huiying Gao, and Yu Zhang. 2021. "Rural Economic Development Based on Shift-Share Analysis in a Developing Country: A Case Study in Heilongjiang Province, China" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041969

APA StyleLv, D., Gao, H., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Rural Economic Development Based on Shift-Share Analysis in a Developing Country: A Case Study in Heilongjiang Province, China. Sustainability, 13(4), 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041969