Synopsis of Factors Affecting Hydrogen Storage in Biomass-Derived Activated Carbons

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Factors Affecting H2 Storage in Biomass-Derived Activated Carbons

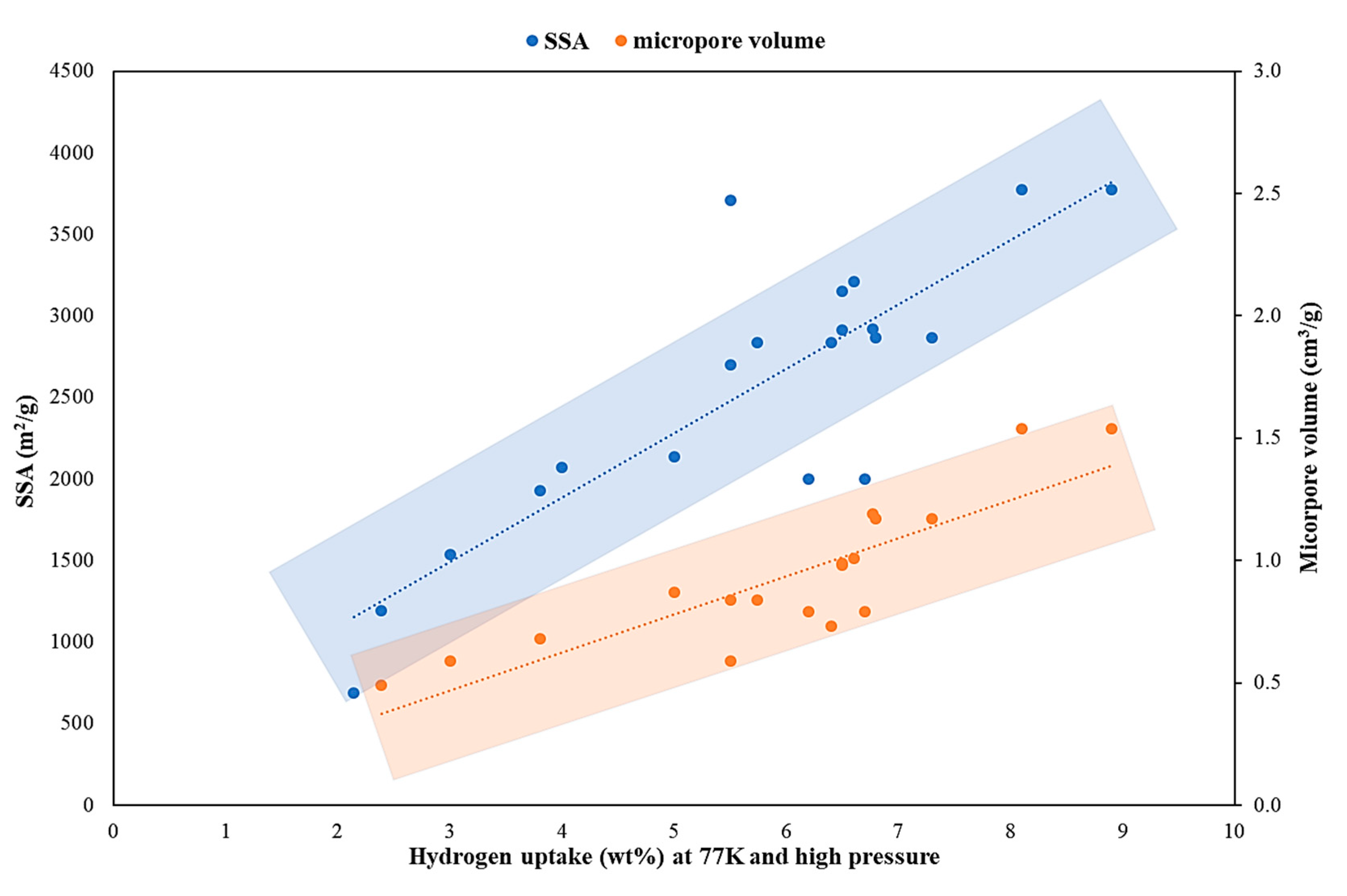

2.1. Role of Surface Morphology of Activated Carbons on H2 Storage

2.2. Role of Surface Functionality of AC on H2 Storage

2.3. Role of Physical Conditions on H2 Storage

2.4. Role of Thermodynamic Properties on H2 Storage

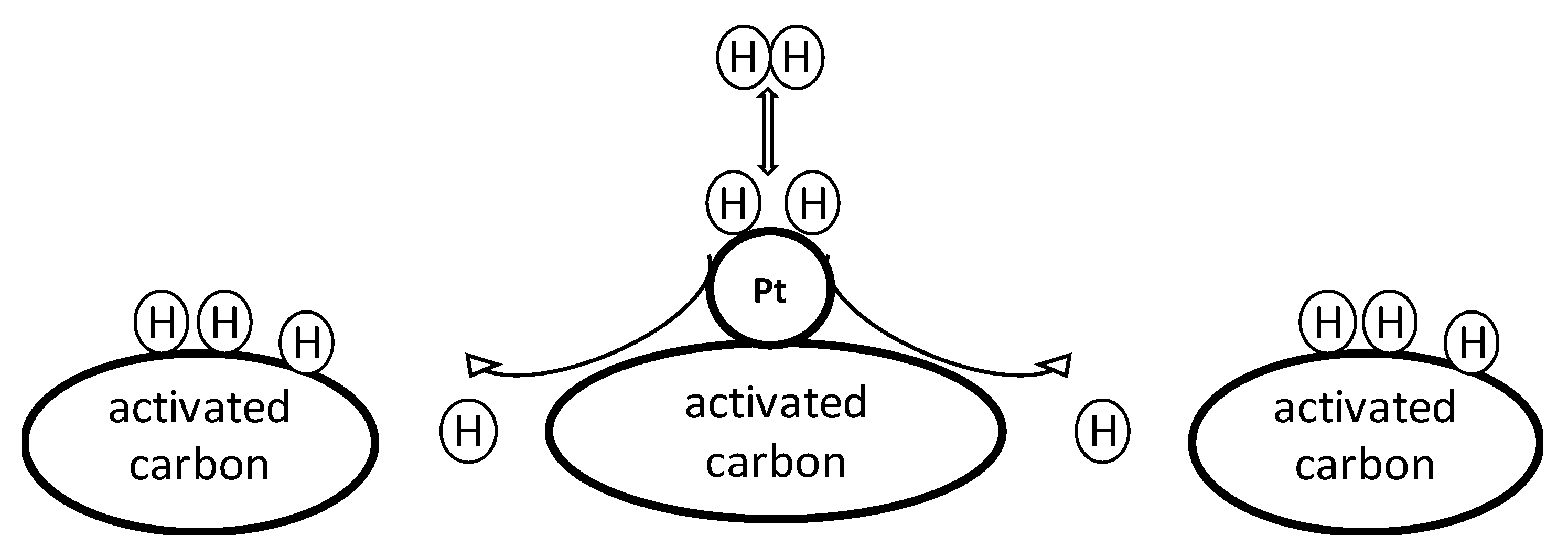

3. Recent Advances in Material Development

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moriarty, P.; Honnery, D. Hydrogen’s role in an uncertain energy future. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2009, 34, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.A. A Realizable renewable energy future. Science 1999, 285, 687–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlapbach, L.; Züttel, A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications. Mater. Sustain. Energy 2011, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenship Ii, T.S.; Balahmar, N.; Mokaya, R. Oxygen-rich microporous carbons with exceptional hydrogen storage capacity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, K.T.; Jensen, T.R.; Akiba, E.; Li, H. Hydrogen—A Sustainable Energy Carrier. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2017, 27, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Road Map to a US Hydrogen Economy. Available online: https://cafcp.org/sites/default/files/Road%2BMap%2Bto%2Ba%2BUS%2BHydrogen%2BEconomy%2BFull%2BReport.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Koroneos, C.; Dompros, A.; Roumbas, G. Hydrogen production via biomass gasification—A life cycle assessment approach. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2008, 47, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamaras, C.M.; Efstathiou, A.M. Hydrogen Production Technologies: Current State and Future Developments. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/cpis/2013/690627/ (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Turner, J.A. Sustainable hydrogen production. Science 2004, 305, 972–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapdan, I.K.; Kargi, F. Bio-Hydrogen production from waste materials. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2006, 38, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I.; Acar, C. Review and evaluation of hydrogen production methods for better sustainability. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 11094–11111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, C.; Dincer, I. Comparative Assessment of hydrogen production methods from renewable and non-renewable sources. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, R.; Buddhi, D.; Sawhney, R.L. Comparison of Environmental and economic aspects of various hydrogen production methods. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, P.; Poullikkas, A. A comparative overview of hydrogen production processes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holladay, J.D.; Hu, J.; King, D.L.; Wang, Y. An Overview of hydrogen production technologies. Catal. Today 2009, 139, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, U.; Felderhoff, M.; Schüth, F. Chemical and physical solutions for hydrogen storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6608–6630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keaton, R.J.; Blacquiere, J.M.; Baker, R.T. Base metal catalyzed dehydrogenation of ammonia−borane for chemical hydrogen storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1844–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluhm, M.E.; Bradley, M.G.; Butterick, R.; Kusari, U.; Sneddon, L.G. Amineborane-based chemical hydrogen storage: enhanced ammonia borane dehydrogenation in ionic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 7748–7749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajo, J.J.; Olson, G.L. Hydrogen storage in destabilized chemical systems. Scr. Mater. 2007, 56, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.-L.; Xu, Q. Liquid organic and inorganic chemical hydrides for high-capacity hydrogen storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 478–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Musyoka, N.M.; Langmi, H.W.; Mathe, M.; Liao, S. Current research trends and perspectives on materials-based hydrogen storage solutions: A critical review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Mokaya, R. Energy Storage applications of activated carbons: Supercapacitors and hydrogen storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1250–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Fuertes, A.B.; Mokaya, R. High Density Hydrogen storage in superactivated carbons from hydrothermally carbonized renewable organic materials. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S.; Jeder, A.; Sdanghi, G.; Gadonneix, P.; Abdedayem, A.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Maranzana, G.; Ouederni, A.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Oxygen-Promoted Hydrogen Adsorption on Activated and Hybrid Carbon Materials. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Mokaya, R. Enhanced hydrogen storage capacity of high surface area zeolite-like carbon materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1673–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masika, E.; Mokaya, R. Exceptional gravimetric and volumetric hydrogen storage for densified zeolite templated carbons with high mechanical stability. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.; Mokaya, R. Evolution of optimal porosity for improved hydrogen storage in templated zeolite-like carbons. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 1773–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Foulston, R.; Mokaya, R. Superactivated carbide-derived carbons with high hydrogen storage capacity. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, E.; Chahine, R.; Bose, T.K. Hydrogen adsorption in carbon nanostructures. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2001, 26, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Lin, X.; Yang, S.; Blake, A.J.; Dailly, A.; Champness, N.R.; Hubberstey, P.; Schröder, M. Exceptionally High H 2 Storage by a metal–organic polyhedral framework. Chem. Commun. 2009, 1025–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, O.K.; Yazaydın, A.Ö.; Eryazici, I.; Malliakas, C.D.; Hauser, B.G.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Nguyen, S.T.; Snurr, R.Q.; Hupp, J.T. De novo synthesis of a metal–organic framework material featuring ultrahigh surface area and gas storage capacities. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 944–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, H.; Ko, N.; Go, Y.B.; Aratani, N.; Choi, S.B.; Choi, E.; Yazaydin, A.Ö.; Snurr, R.Q.; O’Keeffe, M.; Kim, J. Ultrahigh porosity in metal-organic frameworks. Science 2010, 329, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, M.P.; Park, H.J.; Prasad, T.K.; Lim, D.-W. Hydrogen storage in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 782–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, L.J.; Dincă, M.; Long, J.R. Hydrogen Storage in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1294–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S.-Y.; Wang, W. Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs): From Design to applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 548–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Furukawa, H.; Yaghi, O.M.; Goddard Iii, W.A. Covalent organic frameworks as exceptional hydrogen storage materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 11580–11581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalebrook, A.F.; Gan, W.; Grasemann, M.; Moret, S.; Laurenczy, G. Hydrogen storage: Beyond conventional methods. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 8735–8751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Zeng, J.-L.; Zhang, J.; Xu, F.; Sun, L.-X. Improved hydrogen storage in the modified metal-organic frameworks by hydrogen spillover effect. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 4005–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.-L.; Xu, Q. Metal–organic framework composites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5468–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, Y. Porous carbon-based materials for hydrogen storage: Advancement and challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 9365–9381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, R.; Groth, K.M. Hydrogen storage and delivery: Review of the state of the art technologies and risk and reliability analysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 12254–12269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenship, T.S.; Mokaya, R. Cigarette Butt-derived carbons have ultra-high surface area and unprecedented hydrogen storage capacity. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 2552–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, N.; Ouederni, A. Optimization of biomass-based carbon materials for hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 2016, 5, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.K.; Noh, J.S.; Schwarz, J.A.; Davini, P. Effect of surface acidity of activated carbon on hydrogen storage. Carbon 1987, 25, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro, V.; Zhao, W.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Aylon, E.; Celzard, A. Adsorption and compression contributions to hydrogen storage in activated anthracites. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 9038–9045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, S.S.; Mangisetti, S.R.; Ramaprabhu, S. Investigation of room temperature hydrogen storage in biomass derived activated carbon. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 789, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Webley, P.A. Preparation of activated carbons from corncob with large specific surface area by a variety of chemical activators and their application in gas storage. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 162, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balathanigaimani, M.S.; Haider, M.B.; Jha, D.; Kumar, R.; Lee, S.J.; Shim, W.G.; Shon, H.K.; Kim, S.C.; Moon, H. Nanostructured biomass based carbon materials from beer lees for hydrogen storage. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 2196–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, L.; Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Fan, M.; Zhao, W. Preparation and characterization of heteroatom self-doped activated biocarbons as hydrogen storage and supercapacitor electrode materials. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 325, 134941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Luo, L.; Wang, H.; Fan, M. Synthesis of Bamboo-based activated carbons with super-high specific surface area for hydrogen storage. BioResources 2017, 12, 1246–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasaka, H.; Takahata, T.; Toda, I.; Ono, H.; Ohshio, S.; Himeno, S.; Kokubu, T.; Saitoh, H. Hydrogen storage ability of porous carbon material fabricated from coffee bean wastes. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.-J.; Park, S.-J. Synthesis of Activated carbon derived from rice husks for improving hydrogen storage capacity. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 31, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, G.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Hao, X. Preparation and N2, CO2 and H2 Adsorption of super activated carbon derived from biomass source hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) stem. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 158, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Chen, H.-M.; Chen, C.-H. Hydrogen adsorption on modified activated carbon. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 2777–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel-Iwaniec, I.; Díez, N.; Gryglewicz, G. Chitosan-based highly activated carbons for hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 5788–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, J.; Ma, X. Preparation and adsorption of CO2 and H2 by Activated carbon hollow fibers from rubber wood (hevea brasiliensis). BioResources 2019, 14, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Gao, Q.; Jiang, J. High hydrogen uptake capacity of mesoporous nitrogen-doped carbons activated using potassium hydroxide. Carbon 2010, 48, 2968–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Senkovska, I.; Kaskel, S.; Liu, Q. Chemically activated fungi-based porous carbons for hydrogen storage. Carbon 2014, 75, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, N.; Zacharia, R.; Abdelmottaleb, O.; Cossement, D. How the Activation process modifies the hydrogen storage behavior of biomass-derived activated carbons. J. Porous Mater. 2018, 25, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Geng, Z.; Cai, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Xin, H.; Ma, J. Microstructure regulation of super activated carbon from biomass source corncob with enhanced hydrogen uptake. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2013, 38, 9243–9250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T.; Rajalakshmi, N.; Dhathathreyan, K.S. Synthesis and characterization of activated carbon from jute fibers for hydrogen storage. Renew. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2017, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Yakobson, B.I. Challenges in hydrogen adsorptions: From physisorption to chemisorption. Front. Phys. 2011, 6, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panella, B.; Hirscher, M.; Roth, S. Hydrogen adsorption in different carbon nanostructures. Carbon 2005, 43, 2209–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panella, B.; Hirscher, M.; Pütter, H.; Müller, U. Hydrogen adsorption in metal–organic frameworks: Cu-MOFs and Zn-MOFs compared. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2006, 16, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Foy, A.G.; Matzger, A.J.; Yaghi, O.M. Exceptional H2 Saturation uptake in microporous metal−organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3494–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sur, U.K. Graphene: A Rising star on the horizon of materials science. Int. J. Electrochem. 2012, 2012, 237689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czakkel, O.; Nagy, B.; Dobos, G.; Fouquet, P.; Bahn, E.; László, K. Static and Dynamic studies of hydrogen adsorption on nanoporous carbon gels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 18169–18178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yushin, G.; Dash, R.; Jagiello, J.; Fischer, J.E.; Gogotsi, Y. Carbide-derived carbons: Effect of pore size on hydrogen uptake and heat of adsorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2006, 16, 2288–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogotsi, Y.; Portet, C.; Osswald, S.; Simmons, J.M.; Yildirim, T.; Laudisio, G.; Fischer, J.E. Importance of pore size in high-pressure hydrogen storage by porous carbons. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2009, 34, 6314–6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabria, I.; López, M.J.; Alonso, J.A. The Optimum average nanopore size for hydrogen storage in carbon nanoporous materials. Carbon 2007, 45, 2649–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Mokaya, R.; Fuertes, A.B. Ultrahigh surface area polypyrrole-based carbons with superior performance for hydrogen storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2930–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texier-Mandoki, N.; Dentzer, J.; Piquero, T.; Saadallah, S.; David, P. Hydrogen storage in activated carbon materials: Role of the nanoporous texture. Carbon 2004, 42, 2744–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J. Effect of temperature on activated carbon nanotubes for hydrogen storage behaviors. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 6757–6762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Lee, S.-Y. Hydrogen storage behaviors of platinum-supported multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 13048–13054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Fierro, V.; Zlotea, C.; Aylon, E.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Latroche, M.; Celzard, A. Optimization of activated carbons for hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 11746–11751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedicini, R.; Maisano, S.; Chiodo, V.; Conte, G.; Policicchio, A.; Agostino, R.G. Posidonia oceanica and wood chips activated carbon as interesting materials for hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, S0360319920310922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Dong, H.; Long, C.; Zheng, M.; Lei, B.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. Melaleuca Bark based porous carbons for hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 11661–11667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, J.; Chen, Y.; Hao, X.; Jin, X. Characterization, preparation, and reaction mechanism of hemp stem based activated carbon. Results Phys. 2017, 7, 1628–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, K.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Chunmei, L. preparation and characterization of super activated carbon produced from gulfweed by koh activation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 243, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, F.; Özcan, Ö. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from poplar sawdust by chemical activation: Comparison of different activating agents and carbonization temperature. Eur. J. Eng. Res. Sci. 2018, 3, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hendawy, A.-N.A. An insight into the KOH activation mechanism through the production of microporous activated carbon for the removal of Pb2+ cations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 3723–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaojing Chen, H.Z.; Xiaojing Chen, H.Z. Activation mechanisms on potassium hydroxide enhanced microstructures development of coke powder. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, N.; Xin, D.; Chiu, P.C.; Reza, M.T. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on acidic oxygen-containing functional groups and electron storage capacities of pyrolyzed hydrochars. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 8387–8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhomick, P.C.; Supong, A.; Karmaker, R.; Baruah, M.; Pongener, C.; Sinha, D. Activated carbon synthesized from biomass material using single-step koh activation for adsorption of fluoride: Experimental and theoretical investigation. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 36, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, S.; Xing, G. Comparisons of biochar properties from wood material and crop residues at different temperatures and residence times. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 5890–5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisano, S.; Urbani, F.; Mondello, N.; Chiodo, V. Catalytic pyrolysis of mediterranean sea plant for bio-oil production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 28082–28092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spokas, K.A. Review of the stability of biochar in soils: Predictability of O:C molar ratios. Carbon Manag. 2010, 1, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, S.; Chiodo, V.; Crea, F.; Maisano, S.; Milea, D.; Pettignano, A. Biochar from byproduct to high value added material—A new adsorbent for toxic metal ions removal from aqueous solutions. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 271, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeganfar, F.; Shahsavari, R. Oxygen- and lithium-doped hybrid boron-nitride/carbon networks for hydrogen storage. Langmuir 2016, 32, 13313–13321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakis, M.; Stavropoulos, G.; Sakellaropoulos, G.P. Molecular dynamics study of hydrogen adsorption in carbonaceous microporous materials and the effect of oxygen functional groups. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 1999–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, J.; Pera-Titus, M. Influence of surface heterogeneity on hydrogen adsorption on activated carbons. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 350, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gao, Q.; Hu, J. High hydrogen storage capacity of porous carbons prepared by using activated carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7016–7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, D. Investigation of hydrogen physisorption active sites on the surface of porous carbonaceous materials. Chem. A Eur. J. 2008, 14, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 18th World Hydrogen Energy Conference 2010—WHEC 2010: Proceedings. 4: Parallel Sessions Book: Storage Systems, Policy Perspectives, Initiatives and Cooperations; Stolten, D., Grube, T., Eds.; Schriften des Forschungszentrums Jülich Reihe Energie & Umwelt; Forschungszentrum, IEF-3: Jülich, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-89336-654-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bleda-Martínez, M.J.; Pérez, J.M.; Linares-Solano, A.; Morallón, E.; Cazorla-Amorós, D. Effect of Surface chemistry on electrochemical storage of hydrogen in porous carbon materials. Carbon 2008, 46, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.; Shabani, B. The role of hydrogen in a global sustainable energy strategy. Wires Energy Environ. 2014, 3, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, N.; Ouederni, A. Functionalized and metal-doped biomass-derived activated carbons for energy storage application. J. Energy Storage 2017, 13, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Geng, Z.; Cai, M. High-pressure hydrogen storage and optimizing fabrication of corncob-derived activated carbon. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 194, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T.; Rajalakshmi, N.; Dhathathreyan, K.S. Activated carbons derived from tamarind seeds for hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 2015, 4, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Arshad, S.H.; Ngadi, N.; Aziz, A.A.; Amin, N.S.; Jusoh, M.; Wong, S. Preparation of activated carbon from empty fruit bunch for hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 2016, 8, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichtenmayer, M.; Hirscher, M. The usable capacity of porous materials for hydrogen storage. Appl. Phys. A 2016, 122, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahine, R.; Bose, T. Low-Pressure Adsorption Storage of Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 1994, 19, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, B.; Müller, U.; Trukhan, N.; Schubert, M.; Férey, G.; Hirscher, M. Heat of adsorption for hydrogen in microporous high-surface-area materials. ChemPhysChem 2008, 9, 2181–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhung, S.H.; Kim, H.-K.; Yoon, J.W.; Chang, J.-S. Low-temperature adsorption of hydrogen on nanoporous aluminophosphates: effect of pore size. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 9371–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, H.; Dybtsev, D.N.; Kim, H.; Kim, K. Synthesis, X-ray crystal structures, and gas sorption properties of pillared square grid nets based on paddle-wheel motifs: Implications for hydrogen storage in porous materials. Chem. A Eur. J. 2005, 11, 3521–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.K.; Myers, A.L. Optimum conditions for adsorptive storage. Langmuir 2006, 22, 1688–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yürüm, Y.; Taralp, A.; Veziroglu, T.N. Storage of hydrogen in nanostructured carbon materials. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2009, 34, 3784–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta, L.; Arenillas, A.; Pis, J.J. Carbon materials for H2 storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2009, 34, 4575–4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Torres, M.Z.; Domínguez-Ríos, C.; Cabañas-Moreno, J.G.; Vega-Becerra, O.; Aguilar-Elguézabal, A. The synthesis of ni-activated carbon nanocomposites via electroless deposition without a surface pretreatment as potential hydrogen storage materials. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2012, 37, 10743–10749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, M.; Long, J.R. Hydrogen Storage in microporous metal-organic frameworks with exposed metal sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2008, 47, 6766–6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Wojcieszak, R.; Monteverdi, S.; Mercy, M.; Bettahar, M.M. Hydrogen Storage in nickel catalysts supported on activated carbon. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta, L.; Menéndez, J.A.; Pis, J.J.; Arenillas, A. Improving hydrogen storage in ni-doped carbon nanospheres. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2009, 34, 3070–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Huang, C.-C. Enhancement of hydrogen spillover onto carbon nanotubes with defect feature. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 109, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.T.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z. Hydrogen storage on carbon doped with platinum nanoparticles using plasma reduction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 8277–8281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, R.T. Enhanced hydrogen storage on pt-doped carbon by plasma reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 5956–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharia, R.; Rather, S.; Hwang, S.W.; Nahm, K.S. Spillover of physisorbed hydrogen from sputter-deposited arrays of platinum nanoparticles to multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 434, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-T.; Chou, Y.-W.; Lin, J.-Y. Fabrication and electrochemical activity of ni-attached carbon nanotube electrodes for hydrogen storage in alkali electrolyte. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 3457–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.-P.; Ding, Y.-F.; Zheng, P.-P. Electrodeposition of nickel nanoparticles on functional MWCNT surfaces for ethanol oxidation. J. Power Sources 2007, 166, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, C.; Felten, A.; Ghijsen, J.; Pireaux, J.J.; Drube, W.; Erni, R.; Van Tendeloo, G. Decorating carbon nanotubes with nickel nanoparticles. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 436, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-W.; Sun, T.-J.; Hu, J.-L.; Wang, S.-D. Composites of metal–organic frameworks and carbon-based materials: Preparations, functionalities and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 3584–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; El-Sai, N.; Girgis, B. Evaluation and modeling of high surface area activated carbon from date frond and application on some pollutants. Int. J. Comput. Eng. Res. 2014, 4, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, R.-L. Physical and chemical properties and adsorption type of activated carbon prepared from plum kernels by NaOH activation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 147, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, M.; Alexandre-Franco, M.; Fernández-González, C.; Gómez-Serrano, V. Development of activated carbon from vine shoots by physical and chemical activation methods. Some insight into activation mechanisms. Adsorption 2011, 17, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parambhath, V.B.; Nagar, R.; Ramaprabhu, S. Effect of nitrogen doping on hydrogen storage capacity of palladium decorated graphene. Langmuir 2012, 28, 7826–7833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.-Y.; Tsao, C.-S.; Tseng, H.-P.; Chen, C.-H.; Yu, M.-S. Effects of Oxygen functional groups on the enhancement of the hydrogen spillover of Pd-doped activated carbon. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 441, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Luo, L.; Chen, T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Rao, J.; Feo, L.; Fan, M. Synthesis and characterization of Pt-N-doped activated biocarbon composites for hydrogen storage. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 161, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psofogiannakis, G.M.; Froudakis, G.E. Fundamental studies and perceptions on the spillover mechanism for hydrogen storage. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7933–7943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psofogiannakis, G.M.; Steriotis, T.A.; Bourlinos, A.B.; Kouvelos, E.P.; Charalambopoulou, G.C.; Stubos, A.K.; Froudakis, G.E. Enhanced hydrogen storage by spillover on metal-doped carbon foam: An experimental and computational study. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Lueking, A.D. Effect of surface oxygen groups and water on hydrogen spillover in Pt-doped activated carbon. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 4273–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, F.H.; Yang, R.T. Enhanced hydrogen spillover on carbon surfaces modified by oxygen plasma. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, X.; Xin, H.; Liu, X.; Cai, M. Spillover enhanced hydrogen uptake of Pt/Pd doped corncob-derived activated carbon with ultra-high surface area at high pressure. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 13643–13649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.D.; Ostrom, C.K.; Chen, S.; Chen, A. High-performance Pd-based hydrogen spillover catalysts for hydrogen storage. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 19875–19882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, R.T. New sorbents for hydrogen storage by hydrogen spillover—A review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2008, 1, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Guan, C.; He, Z.; Lu, Z.; Chen, T.; Liu, J.; Tan, X.; Yang Tan, T.T.; Li, C.M. Surface Functionalization-enhanced spillover effect on hydrogen storage of Ni–B nanoalloy-doped activated carbon. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 13663–13668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachawiec, A.J.; Qi, G.; Yang, R.T. Hydrogen storage in nanostructured carbons by spillover: bridge-building enhancement. Langmuir 2005, 21, 11418–11424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, R.T. Molecular hydrogen and spiltover hydrogen storage on high surface area carbon sorbents. Carbon 2012, 50, 3134–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.T. Hydrogen storage on platinum nanoparticles doped on superactivated carbon. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 11086–11094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta, L.; Menéndez, J.A.; Job, N.; Marco-Lozar, J.P.; Pirard, J.P.; Pis, J.J.; Linares-Solano, A.; Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Arenillas, A. Ni-doped carbon xerogels for H2 storage. Carbon 2010, 48, 2722–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cheng, J.; Dailly, A.; Cai, M.; Beckner, M.; Shen, P.K. One-pot synthesis of pd nanoparticles on ultrahigh surface area 3D porous carbon as hydrogen storage materials. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 14843–14850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Precursor | Type | N (wt%) | C (wt%) | O (wt%) | H (wt%) | SSA (m2/g) | Micropore Volume, Vµ (cm3/g) | Total Pore Volume, VT (cm3/g) | H2 Uptake (wt%) | H2 Uptake Pressure (bar) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bamboo | biomass | <0.3 | 46.12 | 33.22 | 6.29 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | [50] |

| hydrochar | 0.48 | 77.1 | 14 | 2.62 | 337 | 0.14 | N/A | 0.86 | 1 | ||

| 1.2 | 40 | ||||||||||

| activated carbon | <0.3 | 90.11 | 5.99 | 0.52 | 3208 | 1.75 | 1.75 | 2.58 | 1 | ||

| 6.6 | 40 | ||||||||||

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3148 | 0.98 | 1.6 | 2.67 | 1 | |||

| 6.5 | 40 | ||||||||||

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2914 | 0.99 | 1.85 | 2.50 | 1 | |||

| 6.50 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Sword-Bean Shells | activated carbon | 1.78 | 65.06 | 30.51 | 2.65 | 1537 | 0.59 | N/A | 2.1 | 1 | [49] |

| 3.0 | 40 | ||||||||||

| 1.39 | 78.42 | 19.35 | 0.84 | 1930 | 0.68 | 0.97 | 2.25 | 1 | |||

| 3.8 | 40 | ||||||||||

| 1.56 | 92.9 | 4.8 | 0.74 | 2702 | 0.84 | 1.48 | 2.52 | 1 | |||

| 5.5 | 40 | ||||||||||

| 1.67 | 96.28 | 1.44 | 0.61 | 2838 | 0.84 | 1.54 | 2.63 | 1 | |||

| 5.74 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Posidonia Oceanica | hydrochar | 1.8 | 58 | 37.5 | 2.8 | 41 | N/A | 0.1 | N/A | N/A | [76] |

| activated carbon | 0.6 | 92.7 | 4.6 | 2.1 | 2810 | N/A | 0.48 | 6.3 | 80 | ||

| Wood Chips | hydrochar | 0.2 | 69.2 | 28.8 | 1.8 | 425 | N/A | 0.11 | N/A | N/A | |

| activated carbon | 0 | 95.6 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 2835 | N/A | 0.73 | 6.4 | 80 | ||

| Melaleuca bark | biomass | 0.51 | 58.13 | 33.45 | 7.91 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | [77] |

| hydrochar | 0.43 | 82.26 | 15.41 | 1.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| activated carbon | 0.35 | 87.66 | 10.98 | 1.01 | 1092 | 0.4 | 0.46 | 1.21 | 10 | ||

| 0.28 | 88.69 | 9.6 | 0.89 | 1806 | 0.64 | 0.82 | 2.16 | 10 | |||

| 0.21 | 91.56 | 7.59 | 0.64 | 3170 | 1.07 | 1.51 | 4.08 | 10 | |||

| 0.19 | 91.89 | 7.39 | 0.53 | 2986 | 0.86 | 1.63 | 3.91 | 10 | |||

| Cellulose Acetate | hydrochar | N/A | 66.2 | 29.9 | 3.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | [4] |

| activated carbon | N/A | 76.1 | 22.8 | 1.1 | 2001 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 3.1 | 1 | ||

| 6.2 | 20 | ||||||||||

| 6.7 | 30 | ||||||||||

| 78.3 | 20.6 | 1.1 | 2864 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 3.4 | 1 | ||||

| 6.8 | 20 | ||||||||||

| 7.3 | 30 | ||||||||||

| 81.4 | 17.9 | 0.7 | 3771 | 1.54 | 1.54 | 3.9 | 1 | ||||

| 8.1 | 20 | ||||||||||

| 8.9 | 30 | ||||||||||

| Beer Lees | activated carbon | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1927 | 0.754 | 0.797 | 2.92 | 1 | [48] |

| 2092 | 0.889 | 1.152 | 2.74 | 1 | |||||||

| 2408 | 1.089 | 1.505 | 2.43 | 1 | |||||||

| Hemp stem | activated carbon | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 922 | 0.4 | 0.49 | 1.57 | 1 | [78] |

| 1365 | 0.48 | 0.73 | 2.58 | 1 | |||||||

| 1917 | 0.78 | 1.02 | 2.81 | 1 | |||||||

| 2368 | 0.88 | 1.27 | 2.72 | 1 | |||||||

| 3018 | 0.68 | 1.73 | 2.94 | 1 | |||||||

| 3241 | 0.74 | 1.98 | 3.28 | 1 |

| Precursor | Surface Area (m2/g) | Micropore Volume (cm3/g) | Temperature (K) | Pressure (bar) | H2 Storage (wt%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | 3771 | - | 77 | 1 | 3.90 | [4] |

| 77 | 20 | 8.10 | ||||

| 298 | 20 | 0.50 | [96] | |||

| Olive stone | 1269 | 0.48 | 77 | 1 | 1.48 | [59] |

| 77 | 25 | 6.11 | ||||

| 298 | 200 | 1.22 | ||||

| Chitosan | 2919 | 1.19 | 77 | 1 | 2.71 | [55] |

| 77 | 20 | 6.77 | ||||

| 77 | 40 | 5.01 | ||||

| Olive pomace | 1192 | 0.49 | 77 | 1 | 1.23 | [97] |

| 77 | 40 | 2.39 | ||||

| 298 | 180 | 0.45 | ||||

| Fungi | 2137 | 0.87 | 77 | 1 | 2.40 | [58] |

| 77 | 20 | 5.00 | ||||

| Corncob | 3708 | 0.59 | 77 | 1 | 3.20 | [98] |

| 77 | 40 | 5.50 | ||||

| 298 | 164 | 1.05 | ||||

| Wood chips | 2835 | 0.73 | 77 | 1 | 2.55 | [76] |

| 77 | 80 | 6.40 | ||||

| 298 | 80 | 0.55 | ||||

| Tamarind seeds | 1784 | 0.64 | 303 | 60 | 1.36 | [99] |

| 323 | 60 | 1.14 | ||||

| 348 | 60 | 0.88 | ||||

| 373 | 60 | 0.81 | ||||

| Empty fruit bunch | 687 | 0.30 | 77 | 1 | 1.97 | [100] |

| 77 | 20 | 2.14 | ||||

| Coffee bean waste | 2070 | 1.1 | 77 | 40 | 4.00 | [51] |

| 298 | 12 | 1.10 |

| Storing Condition | Metal Content | H2 Storage (wt%) | Change in Uptake (%) * | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Dopant | With Dopant | ||||

| 298 K 10 MPa | 10 wt% Pd | 0.6 | 1.80 | 200 | [135] |

| 6 wt% Pt | 0.84 | 1.34 | 60 | [136] | |

| 5.6 wt% Pt | 0.60 | 1.20 | 100 | [137] | |

| 3 wt% Pt | 0.30 | 0.90 | 200 | [114] | |

| 298 K 3 MPa | 1 wt% Ni | 0.15 | 0.53 | 253 | [111] |

| 298 K 20 MPa | 9.7 wt% Ni | very low | 1.00 | N/A | [138] |

| 303 K 6 MPa | 10 wt% Pd | 0.41 | 0.53 | 29 | [54] |

| 303K 5 MPa | 10 wt% Ni | 0.82 | 1.60 | 95 | [109] |

| 298 K 18 MPa | 2.5 wt% Pd/Pt | 1.00 | 1.65 | 65 | [131] |

| 298 K 25 MPa | 1.86 wt% Pd | 0.60 | 1.40 | 133 | [139] |

| 77 K 40 bar | 1.73 wt% Pd | 2.39 | 2.46 | 3 | [97] |

| 298 K 180 bar | 1.73 wt% Pd | 0.45 | 0.52 | 16 | [97] |

| 298 K 180 bar | 1.1 wt% Pt | 0.45 | 0.53 | 18 | [97] |

| 298 K 25 bar | 1.8 wt% Ni | 0.126 | 0.13 | 2 | [97] |

| 1.75 wt% Cu | 0.13 | 6 | |||

| 3.71 wt% Ag | 0.13 | 3 | |||

| 1.91 wt% Ni | 0.09 | −31 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sultana, A.I.; Saha, N.; Reza, M.T. Synopsis of Factors Affecting Hydrogen Storage in Biomass-Derived Activated Carbons. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041947

Sultana AI, Saha N, Reza MT. Synopsis of Factors Affecting Hydrogen Storage in Biomass-Derived Activated Carbons. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041947

Chicago/Turabian StyleSultana, Al Ibtida, Nepu Saha, and M. Toufiq Reza. 2021. "Synopsis of Factors Affecting Hydrogen Storage in Biomass-Derived Activated Carbons" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041947

APA StyleSultana, A. I., Saha, N., & Reza, M. T. (2021). Synopsis of Factors Affecting Hydrogen Storage in Biomass-Derived Activated Carbons. Sustainability, 13(4), 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041947