How Leaders’ Positive Feedback Influences Employees’ Innovative Behavior: The Mediating Role of Voice Behavior and Job Autonomy

Abstract

1. Introduction

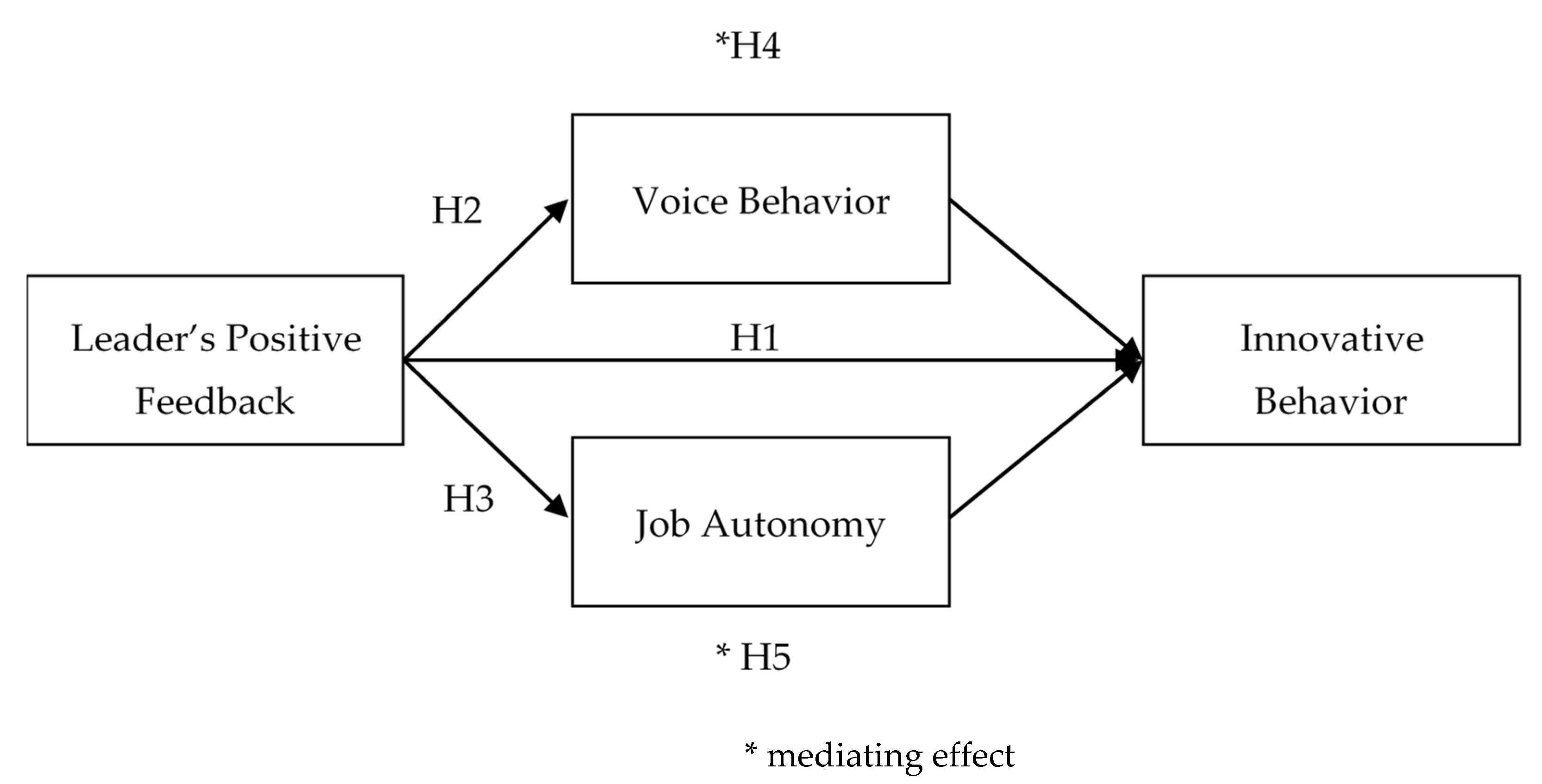

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Leaders’ Positive Feedback and Innovative Behavior

2.2. Leaders’ Positive Feedback and Voice Behavior

2.3. Leaders’ Positive Feedback and Job Autonomy

2.4. Mediating Effect of Voice Behavior

2.5. Mediating Effect of Job Autonomy

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Correlation and Reliability Analyses

4.2. Assessments of Common Method Variance

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ketprapakorn, N. Toward an Asian corporate sustainability model: An integrative review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 117995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audia, P.G.; Brion, S. Reluctant to change: Self-enhancing responses to diverging performance measures. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 102, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.B.; Kang, S.W.; Choi, S.B. Empowering leadership, risk-taking behavior, and employees’ commitment to organizational change: The mediated moderating role of task complexity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigol, T. Influence of authentic leadership on unethical pro-organizational behaviour: The intermediate role of work engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marane, B.M.O. The mediating role of trust in organization on the influence of psychological empowerment on innovation behavior. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 33, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Knol, J.; Van Linge, R. Innovative behaviour: The effect of structural and psychological empowerment on nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, J.B.; Huang, L.; Crede, M.; Harms, P.; Uhl-Bien, M. Leading to stimulate employees’ ideas: A quantitative review of leader–member exchange, employee voice, creativity, and innovative behavior. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 66, 517–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.M.; Higgins, C.A. Champions of technological innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E.E.; Mohrman, S.A.; Ledford, G.E. Creating High Performance Organizations: Practices and Results of Employee Involvement and Total Quality Management in Fortune 1000 Companies; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yidong, T.; Xinxin, L. How ethical leadership influence employees’ innovative work behavior: A perspective of intrinsic motivation. J. Bus. Ethics. 2013, 116, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. The Relationship of Coaching Leadership and Innovation Behavior: Dual Mediation Model for Individuals and Teams across Levels. Open J. Leadersh. 2020, 9, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dai, Y. Coaching Leadership, Job Motivation and Employee Innovation Behavior. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual International Conference on Social Science and Contemporary Humanity Development (SSCHD 2019), Wuhan, China, 15–16 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cameli, A.H.; Meitar, R.; Weisberg, J. Self-leadership Skills and Innovative Behavior at Work. Int. J. Manpow. 2006, 27, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steelman, L.A.; Levy, P.E.; Snell, A.F. The feedback environment scale: Construct definition, measurement, and validation. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2004, 64, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.; Jacobs, A.; Feldman, G.; Cavior, N. Feedback: II. The credibility gap: Delivery of positive and negative and emotional and behavioral feedback in groups. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1973, 41, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Supervisory feedback: Alternative types and their impact on salespeople’s performance and satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, H.J.; Kim, J.S. A field study of the influence of situational constraints leader-member exchange, and goal commitment on performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Parish, J.T.; Cadwallader, S.; Busch, P. Want to, need to, ought to: Employee commitment to organizational change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2008, 21, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, S.J.; Cummings, L.L. Feedback as an individual resource: Personal strategies of creating information. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1983, 32, 370–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; van Knippenberg, B.; de Cremer, D.; Hogg, M.A. Leadership, self, and identity: A review and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 825–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Johnson, D.A.; Moon, K.; Oah, S. Effects of positive and negative feedback sequence on work performance and emotional responses. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2018, 38, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpen, C. The effects of job enrichment on employee satisfaction, motivation, involvement, and performance, A field experiment. Hum. Relat. 1979, 32, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.W. A longitudinal investigation of task characteristics relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 1981, 24, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.P.; Peterson, R.A. Antecedents and consequences of salesperson job satisfaction: Meta-analysis and assessment of causal effects. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, R.M. Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment. Adm. Sci. Q. 1977, 22, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwenk, C.R. Effects of devil’s advocacy on escalating commitment. Hum. Relat. 1988, 41, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. When the presence of creative coworkers is related to creativity: Role of supervisor close monitoring, developmental feedback, and creative personality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eva, N.; Meacham, H.; Newman, A.; Schwarz, G.; Tham, T.L. Is coworker feedback more important than supervisor feedback for increasing innovative behavior? Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 58, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Lin, X.; Ding, H. The influence of supervisor developmental feedback on employee innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, H. Supervisor Feedback and Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Trust in Supervisor and Affective Commitment. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 559160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y. Impact of the supervisor feedback environment on creative performance: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyne, L.; LePine, J.A. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Double loop learning in organizations. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1977, 55, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A.C. Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1419–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Employee voice behavior: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, D.; Rusbult, C.E. Exploring the exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect typology: The influence of job satisfaction, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1992, 5, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J.R.; Burris, E.R. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, R.; Yang, Y. I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identification, and transformational leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Schaubroeck, J. Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, E. Managing for creativity: Back to basics in R&D. R&D Manag. 1986, 16, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of innovative behavior: A pathmodel of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 483–504. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Leiter, M.P. (Eds.) Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Psychology Press: New York, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; De Boer, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 62, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianci, A.M.; Schaubroeck, J.M.; McGill, G.A. Achievement goals, feedback, and task performance. Hum. Perform. 2010, 23, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, E.A.; Tyler, T.R. Critical Issues in Social Justice, The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Jourden, F.J. Self-regulatory mechanisms governing the impact of social comparison on complex decision making. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sias, P.M.; Heath, R.G.; Perry, T.; Silva, D.; Fix, B. Narratives of Work-place Friendship Deterioration. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2004, 21, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Peterson, S.J.; Avolio, B.J.; Hartnell, C.A. An investigation of the relationships among leader and follower psychological capital, service climate, and job performance. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 63, 937–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T.M.; Conti, R.; Coon, H.; Lazenby, J.; Herron, M. Assessing the work environment for creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1154–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, A.O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A.; Van Dyne, L. Predicting voice behavior in work groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R. Group influences on individuals in organizations. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.D., Hough, L.M., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 199–267. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, E.W. Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, E.R.; Detert, J.R.; Romney, A.C. Speaking up vs. being heard: The disagreement around and outcomes of employee voice. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J.R.; Treviño, L.K. Speaking up to higher-ups: How supervisors and skip-level leaders influence employee voice. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.W. Principled organizational dissent: A theoretical essay. Res. Organ. Behav. 1986, 8, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmann, J.; Lanaj, K.; Wang, M.; Zhou, L.; Shi, J. Nonlinear effects of team tenure on team psychological safety climate and climate strength: Implications for average team member performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 940–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Pub: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Development of the job diagnostic survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazanchi, S.; Masterson, S.S. Who and what is fair matters: A multi-foci social exchange model of creativity. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaugh, J.A. The measurement of work autonomy. Hum. Relat. 1985, 38, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.D.; Johnson, J.R.; Hart, Z.; Peterson, D.L. A test of antecedents and outcomes of employee role negotiation ability. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 1999, 27, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.; Vakola, M.; Bourantas, D. Who speaks up at work? Dispositional influences on employees’ voice behavior. Pers. Rev. 2008, 37, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M.; Kim, T.Y.; Wang, J. Dispositional antecedents of demonstration and usefulness of voice behavior. J. Bus. Psychol. 2011, 26, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Van Dyne, L. Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, C.C.; Harlos, K.P. Employee silence: Quiescence and acquiescence as responses to perceived injustice. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2001, 20, 331–369. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, T.S.; Organ, D.W. Job satisfaction and the good soldier: The relationship between affect and employee citizenship. Acad. Manag. J. 1983, 26, 587–595. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiung, H.H. Authentic leadership and employee voice behavior: A multi-level psychological process. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, G.; Zyphur, M.J. Power, Voice, and Hierarchy: Exploring the Antecedents of Speaking Up in Groups. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2005, 9, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Spiegelaere, S.; Van Gyes, G.; Hootegem, G.V. Job design and innovative work behavior: One size does not fit all types of employees. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2012, 8, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S.; Sonnentag, S.; Pluntke, F. Routinization, work characteristics and their relationships with creative and proactive behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bysted, R.; Hansen, J.R. Comparing Public and Private Sector Employees’ Innovative Behavior: Understanding the role of job and organizational characteristics, job types, and subsectors. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistelli, A.; Montani, F.; Odoardi, C. The impact of feedback from job and task autonomy in the relationship between dispositional resistance to change and innovative work behavior. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Farh, C.I.; Farh, J.L. Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neter, J.; Wasserman, W.; Kutner, M.H. Applied Linear Regression Models, 2nd ed.; Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: Essex, UK, 2010; Volume 7, pp. 661–699. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, K.C. The nonlinear effect of green innovation on the corporate competitive advantage. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Edo, M.; Hurtado-Torres, N.E.; Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N. The influence of international scope on the relationship between patented environmental innovations and firm performance. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Konno, N.; Toyama, R. Emergence of “ba”. Knowledge Emergence: Social, Technical, and Evolutionary Dimensions of Knowledge Creation; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2001; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, L.; Ramos, A.; Rosa, A.; Braga, A.C.; Sampaio, P. Stakeholders satisfaction and sustainable success. Int. J. Ind. Syst. Eng. 2016, 24, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Leader’s positive behavior | 3.69 | 0.62 | (0.891) | |||

| 2. Voice behavior | 3.46 | 0.59 | 0.345 *** | (0.907) | ||

| 3. Job autonomy | 3.74 | 0.66 | 0.299 *** | 0.466 *** | (0.835) | |

| 4. Innovative behavior | 3.61 | 0.58 | 0.385 *** | 0.673 *** | 0.423 *** | (0.913) |

| Model | χ2(df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | ∆χ2(df) |

| Hypothesized 4-factor model (LF, VB, JA, IB) | 844.837(414) | 0.955 | 0.949 | 0.044 | |

| 3-factor model (LF, JA, VB and IB) | 11,191.815(417) | 0.918 | 0.909 | 0.059 | 346.978(3) *** |

| 3-factor model (LF and VB, JA, IB) | 1452.945(417) | 0.891 | 0.781 | 0.069 | 608.108(3) *** |

| 2-factor model (LF and JA, VB and IB) | 1797.184(419) | 0.855 | 0.839 | 0.079 | 952.347(4) *** |

| 2-factor model (LF and VB and JA, IB) | 2287.241(419) | 0.803 | 0.781 | 0.092 | 1442.404(5) *** |

| 1-factor model | 2641.014(420) | 0.766 | 0.741 | 0.100 | 1796.177(6) *** |

| Direct Effects | Coefficient | T-Value | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paths | |||

| Leader’s positive feedback→Innovative Behavior(H1) | 0.168 *** | 4.714 | supported |

| Leader’s positive feedback→Voice behavior(H2) | 0.352 *** | 8.619 | Supported |

| Leader’s positive feedback→Job autonomy(H3) | 0.309 *** | 7.464 | Supported |

| Voice behavior→Innovative behavior | 0.576 *** | 16.927 | |

| Job autonomy→Innovative behavior | 0.113 *** | 3.383 | |

| χ2 = 844.837 (df = 414, p < 0.000); RMR = 0.028; GFI = 0.905; CFI = 0.955; RMSEA = 0.044; NFI = 0.915; IFI = 0.955; TLI = 0.949. | |||

| Independent Variable | Mediator Variable | Dependent Variable | SMC | Β | 95% CI (Lower-Upper) | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leader’s positive feedback | Voice behavior | Innovative behavior | 0.124 | 0.576 *** | 0.496 | 0.631 | Supported (H4) |

| Leader’s positive feedback | Job autonomy | Innovative behavior | 0.096 | 0.113 ** | 0.038 | 0.158 | Supported (H5) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, W.R.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.-W. How Leaders’ Positive Feedback Influences Employees’ Innovative Behavior: The Mediating Role of Voice Behavior and Job Autonomy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041901

Lee WR, Choi SB, Kang S-W. How Leaders’ Positive Feedback Influences Employees’ Innovative Behavior: The Mediating Role of Voice Behavior and Job Autonomy. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041901

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Wang Ro, Suk Bong Choi, and Seung-Wan Kang. 2021. "How Leaders’ Positive Feedback Influences Employees’ Innovative Behavior: The Mediating Role of Voice Behavior and Job Autonomy" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041901

APA StyleLee, W. R., Choi, S. B., & Kang, S.-W. (2021). How Leaders’ Positive Feedback Influences Employees’ Innovative Behavior: The Mediating Role of Voice Behavior and Job Autonomy. Sustainability, 13(4), 1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041901