Resident-Tourist Value Co-Creation in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Role of Residents’ Perception of Tourism Development and Emotional Solidarity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Value Co-Creation

2.2. Tourism Value Co-Creation

2.3. Heritage Tourism Value Co-Creation

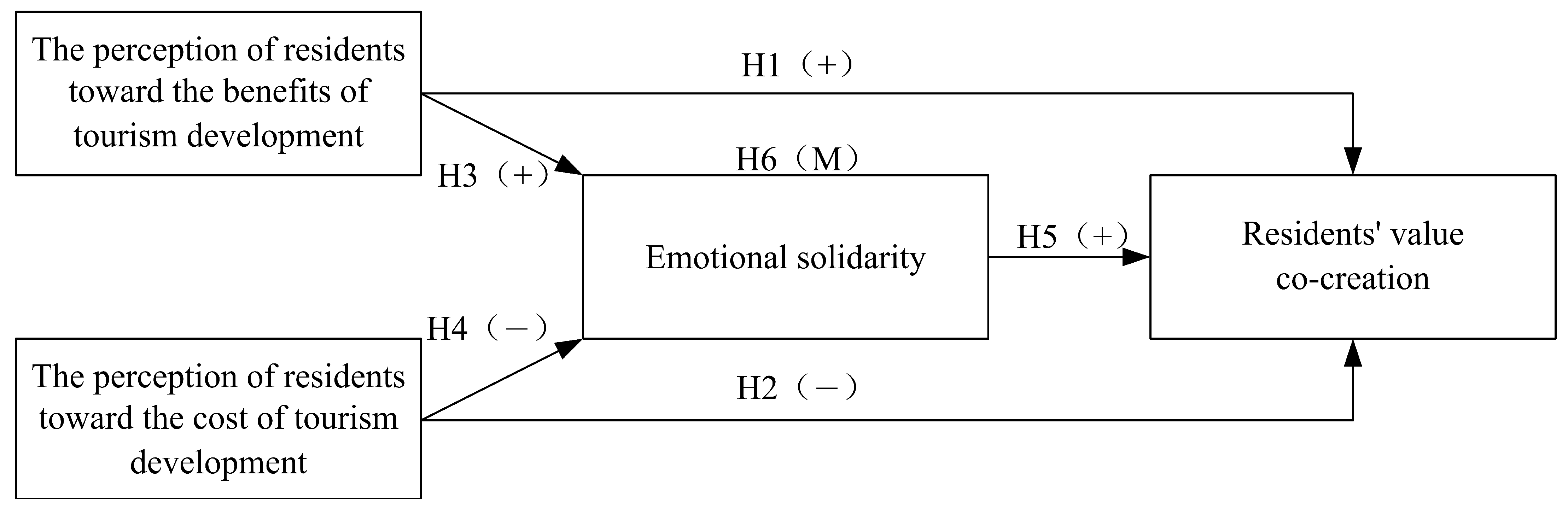

3. Research Hypothesis and Model Design

3.1. The Perception of Tourism Development and Value Co-Creation

3.2. The Perception of Tourism Development and Emotional Solidarity

3.3. Emotional Solidarity and Value Co-Creation

3.4. The Mediating Role of Emotional Solidarity

4. Methodology

4.1. Case Survey

4.2. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

5.2. Reliability and Validity Test

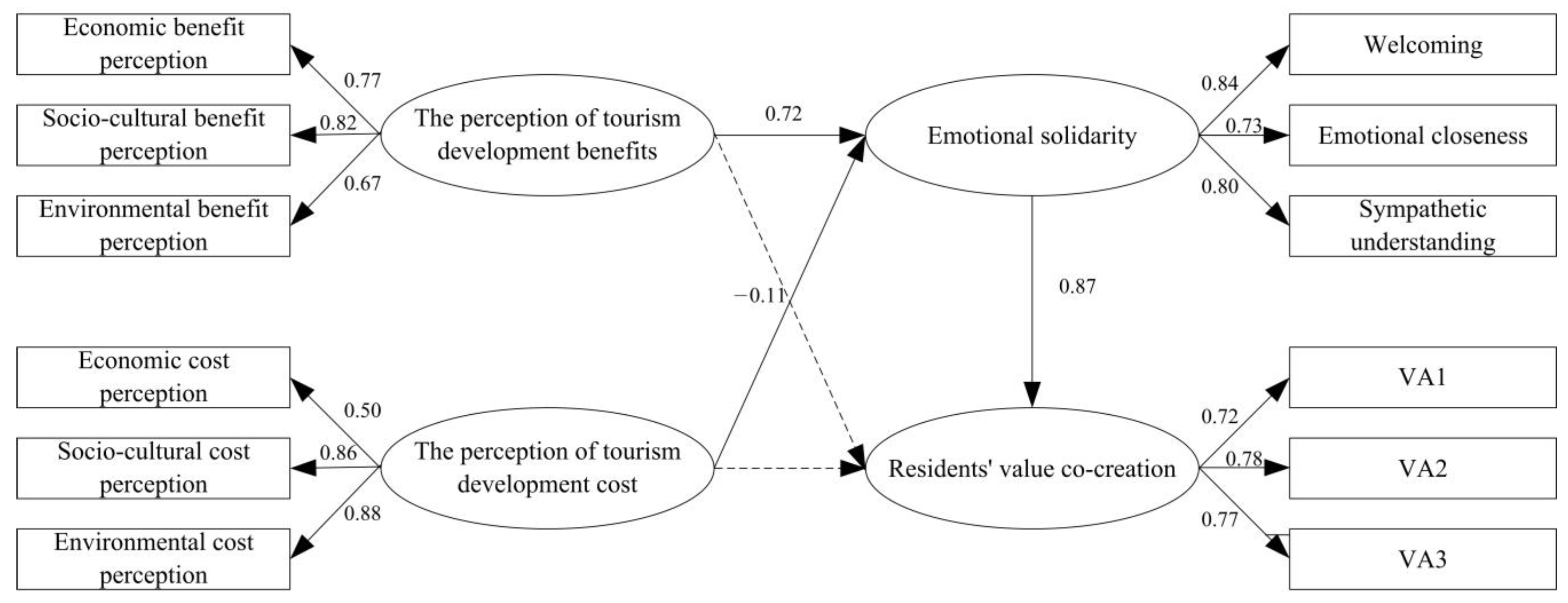

5.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5.4. Model Validation and Analysis

5.5. Mediating Effect Analysis

5.6. Empirical Results

6. Discussion and Conclusion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Binkhorst, E.; Den Dekker, T. Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Vittersø, J.; Dahl, T.I. Value co-creation significance of tourist resources. Ann. Tourism Res. 2013, 42, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Value co-creation in service logic: A critical analysis. Marketing Theor. 2011, 11, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, Q. Value co-creation theory formation path analysis and future research prospects. Int. Econ. Manag. 2012, 34, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Finsterwalder, J.; Tuzovic, S. Quality in group service encounters. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2010, 20, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihova, I.; Buhalis, D.; Moital, M.; Gouthro, M.B. Conceptualising customer-to-customer value co-creation in tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabiddu, F.; Lui, T.; Piccoli, G. Managing value co-creation in the tourism industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, Y.; Filieri, R. Resident-tourist value co-creation: The role of residents’ perceived tourism impacts and life satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, B.; Gustafsson, A.; Pinho, N.; Beirão, G.; Patrício, L.; Fisk, R.P. Understanding value co-creation in complex services with many actors. J. Serv Manag. 2014, 25, 470–493. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Punzo, L.F. Tourist development and host–guest interaction: An economic exchange theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Punzo, L.F. Tourism, residents’ attitudes and perceived carrying capacity with an experimental study in five Tuscan destinations. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 14, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Milito, M.C.; Nunkoo, R. Residents’ support for a mega-event: The case of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, Natal, Brazil. J. Destin Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, D.G.; Wandersman, A. The importance of neighbors: The social, cognitive, and affective components of neighboring. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 1985, 13, 139–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G.; Mathieson, A. Tourism: Change, Impacts, and Opportunities; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Látková, P.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ attitudes toward existing and future tourism development in rural communities. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.R.; Long, P.T.; Perdue, R.R.; Kieselbach, S. The impact of tourism development on residents’ perceptions of community life. J. Travel Res. 1988, 27, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Norman, W.C. Measuring residents’ emotional solidarity with tourists: Scale development of Durkheim’s theoretical constructs. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, S. Host-Tourist Interaction: Emoticon Solidarity and Tourist Loyalty—A Case on Heritage Tourists. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2020, 36, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Norman, W.C.; Ying, T. Exploring the theoretical framework of emotional solidarity between residents and tourists. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Linghu, K.; Li, L. The evolution and prospects of value co-creation research. Int. Econ. Manag. 2016, 38, 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, R. Value co-production: Intellectual origins and implications for practice and research. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-opting customer competence. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolyperas, D.; Maglaras, G.; Sparks, L. Sport fans’ roles in value co-creation. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 19, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjojo, H.; Fontana, A.; Gayatri, G.; Soehadi, A.W. Value co-creation for innovation: Evidence from Indonesian Organic Community. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 32, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntikul, W.; Jachna, T. The co-creation/place attachment nexus. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. Service-dominant logic: Reactions, reflections and refinements. Mark. Theor. 2006, 6, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.; Grönroos, C. Service logic revisited: Who creates value? And who co-creates? Eur. Bus. Rev. 2008, 20, 298–314. [Google Scholar]

- Maglio, P.P.; Spohrer, J. Fundamentals of service science. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohrer, J.; Maglio, P.P.; Bailey, J.; Gruhl, D. Steps toward a science of service systems. Computer 2007, 40, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohrer, J.; Maglio, P.P. The emergence of service science: Toward systematic service innovations to accelerate co-creation of value. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2008, 17, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. From repeat patronage to value co-creation in service ecosystems: A transcending conceptualization of relationship. J. Bus. Mark. Manag. 2010, 4, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. It’s all B2B… and beyond: Toward a systems perspective of the market. Ind. Mark. Manag 2011, 40, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eletxigerra, A.; Barrutia, J.M.; Echebarria, C. Place marketing examined through a service-dominant logic lens: A review. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.X.; Hsu, C.H.; Lin, B. Tourists’ experiential value co-creation through online social contacts: Customer-dominant logic perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 108, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Seo, Y.; Kemper, J. Complaining practices on social media in tourism: A value co-creation and co-destruction perspective. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T.; Rajendran, D.; Rowley, C.; Khai, D.C. Customer value co-creation in the business-to-business tourism context: The roles of corporate social responsibility and customer empowering behaviors. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helkkula, A.; Kelleher, C.; Pihlström, M. Characterizing value as an experience: Implications for service researchers and managers. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Nambisan, S. Service innovation: A service-dominant logic perspective. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, F. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Bailey, A.; Williams, A. Aspects of service-dominant logic and its implications for tourism management: Examples from the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkison, T. The use of co-creation within the luxury accommodation experience–myth or reality? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, E.F.; Kim, H.L.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, J.M.; Prebensen, N.K. The effect of co-creation experience on outcome variable. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihova, I.; Buhalis, D.; Gouthro, M.B.; Moital, M. Customer-to-customer co-creation practices in tourism: Lessons from Customer-Dominant logic. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.; Saxena, G.; Correia, F.; Deutz, P. Archaeological tourism: A creative approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 67, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busser, J.A.; Shulga, L.V. Co-created value: Multidimensional scale and nomological network. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiouras, I.; Skourtis, G.; Giannopoulos, A.; Buhalis, D.; Koniordos, M. Value co-creation and customer citizenship behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.X.; Fong, L.H.N.; Li, S. Co-creation experience and place attachment: Festival evaluation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, U.; Buffa, F.; Notaro, S. Community participation, natural resource management and the creation of innovative tourism products: Evidence from Italian networks of reserves in the Alps. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Sigala, M.; Waligo, V. Social value creation through tourism enterprise. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cottam, E.; Lin, Z. The effect of resident-tourist value co-creation on residents’ well-being. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniccia, P.; Leoni, L.; Baiocco, S. Interpreting sustainability through co-evolution: Evidence from religious accommodations in Rome. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonincontri, P.; Morvillo, A.; Okumus, F.; van Niekerk, M. Managing the experience co-creation process in tourism destinations: Empirical findings from Naples. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharwani, S.; Jauhari, V. An exploratory study of competencies required to co-create memorable customer experiences in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. M 2013, 25, 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosan, C.; DeFranco, A. Co-creating value in hotels using mobile devices: A conceptual model with empirical validation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissemann, U.S.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. Customer co-creation of travel services: The role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijnheer, C.L.; Gamble, J.R. Value co-creation at heritage visitor attractions: A case study of Gladstone’s Land. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; McArthur, S. Integrated Heritage Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, T.H.; Tom Dieck, M.C. Augmented reality, virtual reality and 3D printing for the co-creation of value for the visitor experience at cultural heritage places. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D. Towards meaningful co-creation: A study of creative heritage tourism in Alentejo, Portugal. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2811–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.; Saxena, G. Participative co-creation of archaeological heritage: Case insights on creative tourism in Alentejo, Portugal. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, A.; Telfer, D.J. Transformation of Gunkanjima (Battleship Island): From a coalmine island to a modern industrial heritage tourism site in Japan. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, P.; Gursoy, D.; Sharma, B.; Carter, J. Structural modeling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrubio, C. The impact of spring break behaviour: An integrated threat theory analysis of residents’ prejudice. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Hui, T. Residents’ quality of life and attitudes toward tourism development in China. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Qu, H. The influencing factors of community residents’ attitudes towards tourism development in village heritage sites. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2014, 69, 278–288. [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar, M.; Noor, S.M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Perception of young local residents toward sustainable conservation programmes: A case study of the Lenggong World Cultural Heritage Site. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.T. Residents’ attitudes toward rural tourism in Taiwan: A comparative viewpoint. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Taño, D.; Garau-Vadell, J.B.; Díaz-Armas, R.J. The influence of knowledge on residents’ perceptions of the impacts of overtourism in P2P accommodation rental. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, K.; Johnson, R.L. Modeling resident attitudes toward tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.S.; Pearce, J. How does destination social responsibility contribute to environmentally responsible behaviour? A destination resident perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M. Testing a model of Durkheim’s theory of emotional solidarity among residents of a tourism community. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ivkov, M. Tourists’ emotional solidarity with residents: A segmentation analysis and its links to destination image and loyalty. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.A. Robertson Smith, Durkheim, and sacrifice: An historical context for the elementary forms of the religious life. J. Hist. Behav. Sci. 1981, 17, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarström, G. The construct of intergenerational solidarity in a lineage perspective: A discussion on underlying theoretical assumptions. J. Aging Stud. 2005, 19, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.A.; Wolf, A. Contemporary Sociological Theory Continuing the Classical Tradition. Teach. Sociol. 1995, 15, 434–435. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Pinto, P.; Silva, J.A. Tourists’ destination loyalty through emotional solidarity with residents: An integrative moderated mediation model. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansson, D.H. The grandchildren received affection scale: Examining affectual solidarity factors. South. Commun. J. 2013, 78, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Woosnam, K.M. Measuring tourists’ emotional solidarity with one another—A modification of the emotional solidarity scale. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 1186–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M. Using emotional solidarity to explain residents’ attitudes about tourism and tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wan, Y.K.P. Residents’ support for festivals: Integration of emotional solidarity. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.L. Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hasani, A.; Moghavvemi, S.; Hamzah, A. The impact of emotional solidarity on residents’ attitude and tourism development. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wearing, S.; Wearing, B. Conceptualizing the selves of tourism. Leis. Stud. 2001, 20, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breckler, S.J. Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshinloye, K.D.; Fu, X.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Tasci, A.D. The influence of place attachment on social distance: Examining mediating effects of emotional solidarity and the moderating role of interaction. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 828–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuo, Y.S.S.; Ryan, C.; Liu, G.M. Taoism, temples and tourists: The case of Mazu pilgrimage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. Structural Equation Model: Amos Operation and Application; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, D. General Psychology; Beijing Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Aleshinloye, K.D.; Maruyama, N. Solidarity at the Osun Osogbo Sacred Grove—A UNESCO world heritage site. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2016, 13, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Draper, J.; Jiang, J.K.; Aleshinloye, K.D.; Erul, E. Applying self-perception theory to explain residents’ attitudes about tourism development through travel histories. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.C.; Mendes, J.; Valle, P.O.D.; Scott, N. Co-creation of tourist experiences: A literature review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Theory and Perspective | Participants Who Create Value | Important Theoretical Scholars |

|---|---|---|

| Early service dominant logic | Enterprises and customers are the main participants of value creation, and all social and economic participants are resource integrators. | Vargo & Lusch (2004, 2006, 2008) [24,28,29] |

| Service Logic | Enterprises, customers and suppliers are the main participants of value creation | Grönroos (2008, 2011) [3,30] |

| Service Science | Between the internal members of the complex service system and the service system (focusing on the role and function of technology) | Maglio, Spohrer, Vargo, Lusch, et al. (2007, 2008, 2010, 2011) [31,32,33,34,35] |

| Service Eco-system | All participants who create value together are dynamic network systems, always including beneficiaries; all social and economic participants are resource integrators. | Vargo & Lusch (2010, 2011, 2014, 2016) [34,35,36] |

| Indicator Name. | CMIN/DF | RMSEA | RMR | GFI | AGFI | NFI | RFI | IFI | TLI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation standard | CMIN/DF < 3 | RMSEA < 0.08 | RMR < 0.05 | GFI > 0.9 | AGFI > 0.9 | NFI > 0.9 | RFI > 0.9 | IFI > 0.9 | TLI > 0.9 | CFI > 0.9 |

| Initial model fitting value | 4.478 | 0.090 | 0.037 | 0.919 | 0.869 | 0.917 | 0.887 | 0.935 | 0.910 | 0.934 |

| Initial model adaptation judgment | Accep-table | No | Good | Good | Accep-table | Good | Accep-table | Good | Good | Good |

| Model fitting value after optimization | 3.578 | 0.078 | 0.036 | 0.941 | 0.901 | 0.937 | 0.909 | 0.954 | 0.933 | 0.953 |

| Model adaptation judgment after optimization | Acceptable | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Variable Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Standard Regression Coefficient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value co-creation participation | <--- | Economic benefit perception | 0.251 | 0.078 | 3.208 | 0.001 | 0.291 |

| Value co-creation participation | <--- | Socio-cultural benefit perception | 0.312 | 0.095 | 3.291 | 0.001 | 0.327 |

| Value co-creation participation | <--- | Environmental benefit perception | 0.050 | 0.053 | 0.943 | 0.345 | 0.061 |

| Value co-creation participation | <--- | Economic cost perception | 0.230 | 0.073 | 3.133 | 0.002 | 0.239 |

| Value co-creation participation | <--- | Socio-cultural cost perception | −0.128 | 0.064 | −2.019 | 0.044 | −0.222 |

| Value co-creation participation | <--- | Environmental cost perception | −0.078 | 0.077 | −1.015 | 0.310 | −0.106 |

| Emotional solidarity | <--- | Economic benefit perception | 0.107 | 0.067 | 1.593 | 0.111 | 0.129 |

| Emotional solidarity | <--- | Socio-cultural benefit perception | 0.314 | 0.083 | 3.780 | *** | 0.341 |

| Emotional solidarity | <--- | Environmental benefit perception | 0.243 | 0.049 | 4.998 | *** | 0.307 |

| Emotional solidarity | <--- | Economic cost perception | 0.223 | 0.065 | 3.429 | *** | 0.249 |

| Emotional solidarity | <--- | Socio-cultural cost perception | −0.123 | 0.056 | −2.192 | 0.028 | −0.228 |

| Emotional solidarity | <--- | Environmental cost perception | −0.128 | 0.068 | −1.886 | 0.059 | −0.189 |

| Interval | Variable | Tourism Development Benefit Perception | Tourism Development Cost Perception | Emotional Solidarity | Value Co-Creation Participation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limit | Emotional solidarity | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Value co-creation participation | 0.741 | −0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Lower limit | Emotional solidarity | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Value co-creation participation | 0.401 | −0.196 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| S/N | Hypothetical Content | Test Result |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | The perception of residents toward the benefits of tourism development has a significant positive impact on their value co-creation. | Established |

| H2 | The perception of residents toward the cost of tourism development has a significant negative impact on their value co-creation. | Established |

| H3 | The perception of tourists toward the benefits of tourism development has a significant positive impact on their emotional solidarity toward tourists. | Established |

| H4 | The perception of tourists toward the cost of tourism development has a significant negative impact on their emotional solidarity toward tourists. | Established |

| H5 | The emotional solidarity of residents toward tourists has a significant positive impact on their value co-creation. | Established |

| H6 | Emotional solidarity plays a mediating role between the perception of residents toward tourism development and value co-creation. | Established |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lan, T.; Zheng, Z.; Tian, D.; Zhang, R.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Resident-Tourist Value Co-Creation in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Role of Residents’ Perception of Tourism Development and Emotional Solidarity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031369

Lan T, Zheng Z, Tian D, Zhang R, Law R, Zhang M. Resident-Tourist Value Co-Creation in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Role of Residents’ Perception of Tourism Development and Emotional Solidarity. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031369

Chicago/Turabian StyleLan, Tianning, Zhiyue Zheng, Di Tian, Rui Zhang, Rob Law, and Mu Zhang. 2021. "Resident-Tourist Value Co-Creation in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Role of Residents’ Perception of Tourism Development and Emotional Solidarity" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031369

APA StyleLan, T., Zheng, Z., Tian, D., Zhang, R., Law, R., & Zhang, M. (2021). Resident-Tourist Value Co-Creation in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Role of Residents’ Perception of Tourism Development and Emotional Solidarity. Sustainability, 13(3), 1369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031369