Abstract

Developing the sustainable thinking of students is an important preoccupation of specialists, teachers, and civil society. Information literacy represents the development of students’ skills to search, identify, evaluate, and ethically use scientific information. Is there a connection between sustainable thinking (ST) and information literacy (IL)? Through a scientometric study in the Web of Science (WOS) database, the authors identify clusters of keywords, analyze the articles identified in WOS, and identify the main research directions and the existing concepts. At the same time, a qualitative research study is performed regarding the opinions of students who participated in the IL class. By corroborating and interpreting the results obtained by the two previously mentioned research, the authors demonstrate a close correlation between the two, thus creating an extended map of these concepts, a limited map of the concepts used, and a theoretical map of the concepts. The connection between information literacy and the development of ST is demonstrated, thus creating the premise for a new research direction.

1. Introduction

It is claimed and demonstrated that higher education institutions (HEIs) play a major role in readying the future generations for a sustainable society [1,2,3], thus approaching different aspects of achieving this challenge of the present society [4].

Many studies discuss the issue of awareness, as well as educating and training students, for a sustainable society by creating an adequate curriculum [1,5,6,7,8].

Another approach that does not exclude the importance of curriculum is the one identifying new means of teaching, such as “photovoice methodology” [1]; performing specific activities in the form of task or practice [9,10]; creating a problem [11] or reflection [12]; or even approaching sustainability as a moral issue [13].

Sustainability challenges are complex and call for the effective development of knowledge, skills, and abilities [12], but we know little about how to teach students this complex subject [14]. It has been stated that teachers have inadequate knowledge of sustainability [15], and there is a lack of understanding about sustainable development education (of both individuals and institutions), thus creating a disproportion between knowledge and practice in higher education [16].

The education process is tied to the act of research. The development of society and the current challenges have allowed for a significant evolution of online research, thus the statement “the search and evaluation of information found on the internet is certainly an important component” is of importance [17]. Information literacy (IL) is “a set of abilities requiring individuals to recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” [18] and is seen “as a key to social, cultural, and economic development of nations, communities, institutions, and individuals” [19]. It has also been shown that we must create a background for developing knowledge and skills in order to adapt to “research-informed SD practices” [16]. Regarding the previous statement, universities can do more to support the sustainable development goals (SDGs) by working with faculty, staff, and students, [20] as well as with their wider stakeholder community and alumni body [3]. We consider it appropriate to add the component of university libraries. This addition is supported by the fact that libraries, due to their role of informing the public (students, faculty, staff, and researchers), also support the curriculum [8], as they are places where current technology, facilities, services, and environments are provided in accordance with the expectations and characteristics of the target audience [21].

In a small-scale pilot study onthe IL skills of law students and their ability to find information about environmental protection, these skills and abilities were correlated with the involvement of libraries in such projects and the accreditation of an IL course offered by the library [22].

We must also keep in mind the role of the librarian in forming the IL skills of the students in the present context of the user-centered approach, which requires developing disciplinary expertise and research abilities in a certain field of interest [23]. There have been studies on research abilities and sustainable development, whether as a general competence or one associated with the learning process; the conclusion was that “a holistic view on how both concepts are linked is missing” [24].

A bibliometric study conducted in 2015–2018 [25] concerning the great amount and diversity of information regarding sustainable development after the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were proposed by the UN in 2015 [26] found that the research abilities obtained by an adequate IL are not only necessary but also important concerning environmental sustainability. In this sense, during the IL course taught at the Faculties of Product Design and Environment, Sociology and Communication within the Transilvania University of Brașov, information was presented to develop sustainable thinking. Most importantly, it was intended to change people’s minds towards valuing sustainability [27]. The development of sustainable thinking (ST) involves learning about and understanding the concept of sustainable development, as well as the link between the multiple global crises and unsustainable economic activities [27]. ST intervenes between needs and environmental issues, effectively determining the incorporation of environmental consideration and application [28,29].

A direct connection can be considered to the carbon footprint left each time we search for information on the internet. Starting with this information contained in IL, the present article demonstrates, by scientometric study and qualitative statistical research, the connection between IL and the development of ST. This research is related to the concept of the integrative application of ST [30] by introducing the elements of sustainable environmental development in IL courses.

2. Materials and Methods

In carrying out the paper, starting with the practical situation of ST development through IL courses, we considered it necessary to use two different research methods: a scientometric study and a qualitative statistical research.

Through the first method, the scientometric study, we wanted to explore the current state of research and the vision and opinions of researchers on achieving the goals of sustainable development through ST and the methods of developing ST. The interpretation of the obtained results was concretized in the elaboration of two maps: an extended map of the used concepts and a limited map of the used concepts.

The second method, namely qualitative statistical research was to validate the hypotheses: (i) IL courses develop sustainable thinking by introducing the presentation of the impact of information technologies on the environment, and (ii) the development of digital information retrieval skills reduce the carbon footprint and develops sustainable thinking and sustainable informational behavior.

2.1. Scientometric Study

The scientometric study was conducted by (i) querying the Web of Science (WOS) database, (ii) identifying clusters of keywords, and (iii) analyzing the articles identified in order to determine the main directions of research and existing concepts.

2.1.1. Stages of the Scientometric Study

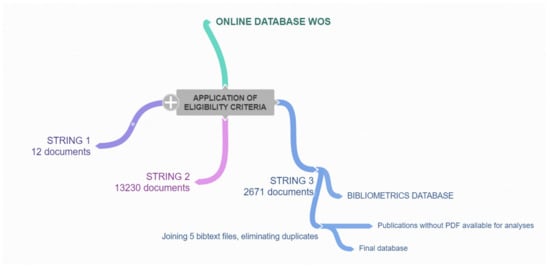

The scientometric study starts with the phrasing of the problem (the filing and bibliometric analysis of publications that use the descriptive terms), establishing the research protocol (STRING 1, STRING 2, STRING 3) and eligibility criteria, and extracting data, which were subsequently analyzed, synthesized, and discussed.

The research stage, which consisted of applying STRING 1, containing all requirements/criteria established as necessary for the study [educationANDSustainabilityAND“ information literacy”], resulted in only 12 articles, which required the introduction of STRING 2 to reduce the criteria to [“education”ANDSustainability]. This stage generated 13,230 documents, which were refined with STRING 3 for the period of 2016–2020, thus resulting in 2671 documents. The period 2016–2020 was chosen as a result of the proposal in 2015 by the UN of the SDGs.

This methodological procedure is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The procedure.

Analyzing the results of the three queries shows that although the interest in education for sustainability is very high: application of STRING 2 resulted in 13,230 documents, and the application of STRING 3 resulted in 2671 documents, only a small part of which are dedicated to interference between the three areas: education, sustainability, and IL, which gives topicality to our research topic.

2.1.2. The Map of Concepts Resulted from STRING 1

The analysis of interrogation of STRING 1 shows that only a part of the identified articles (8 out of 12) meet the strict demands of the research field, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of interrogation of STRING 1.

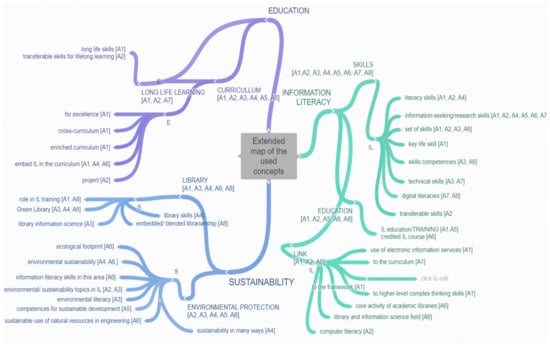

The analysis of the concepts used, which are adequate to the present study, made it possible to create an extended map of the common concepts for each of the three criteria of STRING 1 interrogation, as seen in Figure 2. The map was made by associating each of the three search terms (education, sustainability, and IL) with the common concepts identified for each term (long-life learning (LLL) and curriculum; library and environmental protection; skills, education, and links) and extending with their associated terms, identified in the articles studied and presented in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Extended map of the used concepts.

We can see that there is a connection between the researched articles by using, within the current context, some common terms, grouped according to the three STRING 1 interrogation criteria as follows:

- -

- When the authors refer to education (purple line), they connect with (i) the long-life learning process (LLL) and the associated abilities and (ii) the curricula, on which, in the opinion of the authors, it is necessary to intervene (cross-curricula, enriched, embed) going even towards a curriculum for excellence;

- -

- In regard to sustainability (blue line), the terms that were used were grouped into two areas: libraries and environmental protection. The first group of concepts, associated with libraries, refers to a green library, its role in IL training and obtaining library skills, to library information science and embedded/blended librarianship. The group of terms associated with environmental protection shows the connection determined by the alphabetization in this domain by acquiring competence and skills and by the sustainable use of natural resources or ecological footprint.

- -

- The terms used by the authors when they made the connection with IL (green line) were grouped into three major categories: skills, education, and link. The skills category can be grouped into (i) learning, information, search, and research skills and (ii) technical, transferable skills needed for competence or for life. Skills can, in turn, be grouped into skills (i) for learning, information, search, and research and (ii) technical, transferable skills or life skills. In a close sense to IL, the term “digital literacies” is also used. In the second category, IL was associated with education in the common sense of the word (IL education/training) but also in regard to the need to have credited IL courses for all students. The third category, Link, supports IL’s connection with (i) the library (its main activity and library and information science field), (ii) use of electronic information services and computer literacy, (iii) the forming of higher-level complex thinking skills, curriculum, and the background needed to obtain it.

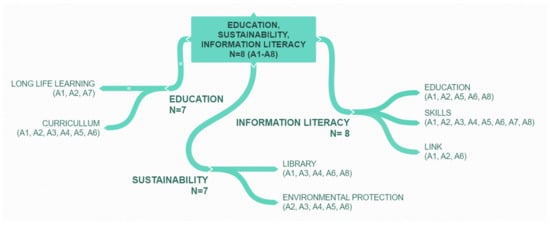

In order to easily use this map, it required its conceptual limitation so as the result was materialized in a conceptual limited map (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Limited map of the used concepts.

We can easily notice that all 8 articles [N = 8 A1–A8] corresponding to STRING 1 are only found in the “SKILLS” subcategory, which is within the “INFORMATION LITERACY” category.

These two maps (extended map of the used concepts and limited map of the used concepts) were used to create a Theoretical map for developing ST of the students by including IL in all forms of education.

2.2. Statistical Research

For statistical research, (i) the aspects regarding IL and one of the most substantial problems specific to sustainable development—energy consumption and the subsequent carbon footprint left by this consumption—were combined, and (ii) the connection between IL and the development of ST was demonstrated.

Other aspects of energy use, such as a problem of HEIs in reaching the goals of sustainable development, were researched by specialty literature [33]; thus a conclusion was reached that points out the lack of general knowledge regarding the energetic context of the academic community [34].

Reducing the carbon footprint has been studied in terms of transitioning to not using paper courses, which would have a significant positive impact [35].

2.2.1. Presentation and Means of Statistical Research

The first objective of this research was to investigate whether the IL course, with information regarding the influence of informational behavior in increasing environmental sustainability, will generate a desire for the students to learn useful strategies in searching for information. Can the IL course develop and help implement an ST?

The second objective was to verify the existence of potential significant differences between different groups of students, grouped according to age, year of study, or gender.

The research method was inquiry, and the tool was a ten-question questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed by using the online platform Survey Monkey. In order to apply this questionnaire, the Ethics Committee from Transilvania University of Brașov provided its approval.

The study was performed on a population of 336 students during March–July 2020. It was desired that the population to whom the questionnaire was applied to was representative; thus, the target group was formed of the students who participated in the information literacy course, the module Development of ST.

2.2.2. Presentation of Questions and Results and Their Interpretation

The first part of the questionnaire contained information regarding the reason for this research, confidentiality of information, and the agreement regarding the participation in the study, which was agreed upon by filling out the questionnaire. No personal data were collected. Study participants included 336 students of Transilvania University of Brașov, including students of Engineering, Communication and Public Relations, and Digital Media. The number of respondents represents 95% of the number of students from these specializations. The students were presented with information regarding the sustainability of the environment and the influence of the means by which we access information resources in generating the carbon print. For a clearer vision of the statistical research carried out, together with the presentation of each question, we can find the results obtained and their interpretation:

- Question 1: “Is the presented information new to you? If it is not new, please note in the comments section what the context was in which you became aware of such information?” This validates the premise of the novel character in establishing a connection between IL and ST; 98.81% of respondents showed that this information was new to them.

- Question 2: “Which sources of information do you prefer?” This is to check if the skills acquired by IL are necessary/will be necessary, by identifying the sources of information of the respondents. Although only 17.42% of the respondents prefer electronic sources of information, 72.79% of them search for their information from both printed sources and electronic sources, which validates the character of the necessity of the skills acquired by IL.

- Question 3: “Do you believe that the information which was presented has an impact on those who use electronic sources of information?” This allows the respondents to analyze the information they have received and decide whether it will have an impact on their online research behavior. We notice that 27.38% of the respondents are undecided and a low percentage of respondents, 4.76%, show that the information they received will not cause any behavioral impact, and 67.86% of the respondents answer positively.

- Question 4: “Does IL help you develop research information skills in the appropriate sources and as quickly aspossible? Do you believe that these skills significantly reduce the carbon emissions and the use of electricity when searching for information?” This establishes the connection between IL and ST starting from the basic information that one access action releases 10 mg of CO2 and that the ability to efficiently search for information can be obtained by IL. This connection is validated by the positive answer of 74.25% of respondents. The increase in percentage, as opposed to the answers given toquestion 3, are owed to the migration of undecided respondents who this time are just 22.16% of them. We also notice a slight decrease (3.59%) in the number of respondents who state that the research abilities acquired by IL will have no effect in reducing the energy use and the carbon print.

- Question 5: “In your opinion, can IL determine ST? 1—Very much, 2—a lot, 3—a little, 4—not at all.” This shows the connection between IL and ST. Thus, if question 4 validates the connection, question 5 determines the influence of IL on ST. It is important to notice that 32.34% of respondents declared that IL very much influences ST, 55.99% of respondents stated that IL influences ST a lot, and only 11.68% of respondents believed that the influence of IL over ST is insignificant. None of the respondents deny the influence of IL on ST.

- Question 6: “Are these explanations useful for your activities so as to change your behavior in searching information by using the techniques learned in IL class? Comment.” This determined the personal involvement of respondents in regard to environmental sustainability.

The answers to question 6:

(i) validate the answers to question 4, which establishes a generic connection between IL and ST, because:

- -

- 79.64% said YES, compared to 74.25% positive answers to question 4,

- -

- 16.77% stated I DON’T KNOW, compared to 22.16% undecided answers to question 4,

- -

- 3.59% said NO, identical with the negative answers to question 4 and

(ii) more importantly, demonstrates that the IL course can develop and implement an ST.

- 7.

- Question 7: “How much time do you spend on the daily?” This shows the fact that the most significant daily use of internet is of 4 h daily (38.81%) and 5 h (32.24%), followed by 3 h (12.54%), 6 h (8.06%), 2 h (3.88%), more than 8 h (2.09%), 8 h (1.49%), and 7 h (0,90%). There were no respondents who used the internet 0 h (0.00%).

- 8.

- Question 8: “Year of study” shows the division of respondents according to study cycles as follows: (i) first year of college, 18.75% (63 respondents); second year, 19.64% (66 respondents); third year, 21.43% (72 respondents); fourth year, 21.43% (72 respondents); (ii) master’s studies,15.18% (51 respondents); (iii) Ph.D. students, 3,57% (12 respondents). The study year shows us a division of the respondents by study cycles, which was balanced: the bachelor cycle: year I, 18.75% (63 respondents); year II, 19.64% (66 respondents); year III, 21.43% (72 respondents); year IV, 21.43% (72 respondents); master’s degree, 15.18% (51 respondents); doctorate, 3.57% (12 respondents).

- 9.

- Question 9: “Your gender” shows the following results: 58.01% of respondents were males and 41.99% of respondents are females. Five of the respondents did not indicate their gender.

- 10.

- Question 10: “Your age”.Groups of respondents were as follows: 11.04% between 18 and 20 years, 8.06% were 20 years old,11.94% were 21 years old, 15.22% were 22 years old, 21.79% were 23 years old, 23.88% were 24 years old, 3.28% were 25 years old, 4.78% are between 25 and 30 years old, and 0,00% are over 30 years old. One respondent did not declare his age.

2.2.3. Method and Materials Used to Correlate Statistical Data

In order to reach the second objective of the study and also to validate the existence of the connection between IL and ST, we performed a statistical analysis by using the SPSS 21 program. First, the internal consistency of the items of the questionnaire was checked. The Alpha Cronbach coefficient obtained had the value 0.716, so questionnaires had good consistency.

Next, we realized a correlation between the obtained answers to (i) questions 3, 8, and 9; (ii) questions 4 and 9; and (iii) questions 3 and 7.

In order to achieve correlation, Table 2 and Table 3 show the characteristics of each lot and the descriptive statistics.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics I.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics II.

The results obtained and their interpretation are presented in Section 3.

3. Results

3.1. The Existence of the Connection between IL and ST

Although the answers received to the questionnaire addressed to students show the existence of a connection between IL and ST, it is important to validate these first results by correlating statistical data and establishing the existence of potentially significant differences between different groups of students, grouped according to age, year of study, or gender within this correlation.

3.1.1. Correlation between Answers Obtained for Questions 3, 8, and 9

By checking if there are significant differences between the respondents who believe this information has an impact on those who use electronic information sources depending on their year of study, we noticed that, out of the 228 subjects who believed that this information has an impact on those use electronic sources: 36 (15.8%) were first-year students, 51 (22.4%) were second-year students, 42 (18.4%) were third-year students, 44 (19.3%) were in masters studies, and 12 (5.3%) are Ph.D. students (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cross-tabulation 1.

By correlating the answer to the third question, which shows the belief of respondents that information has an impact on those who use electronic resources, we notice, in the Chi-Square Tests Table, that the test results are significant χ2 [10] = 34,551, p = 0,00; thus, there is an interdependency that is statistically significant between these two variables (Table 5).

Table 5.

Chi-square test 1.

By checking to see if there were significant differences between the subjects who believed that this information has an impact on those who use the electronic sources depending on the gender of the respondents, we noticed that, out of the 225 subjects who believed that information has an impact on those who use electronic sources, 137 were males and 88 were females (Table 6).

Table 6.

Cross-tabulation 2.

By analyzing the correlation between the respondents’ belief that information has an impact on those who use electronic sources of information and their gender, we noticed in the Chi-Square Tests Table (Table 7) that the test results are significant χ2 [2] = 2.909, p = 0.233; thus, there is no significant statistical interdependency between the two variables.

Table 7.

Chi-Square 2.

3.1.2. Correlation between the Answers to Questions 4 and 9

By checking to see if there were significant differences between, on the one hand, the subjects who believed that this information helps obtain searching abilities and that they substantially reduce carbon emission and use of electricity, and on the other hand, the gender of respondents, we noticed that, out of the subjects who believe that this information has an impact on those who use electronic sources of information, 146 were males and 98 were females (Table 8).

Table 8.

Cross-tabulation 3.

By correlating the question “Does information literacy help you develop information searching abilities in the most appropriate sources and the shortest period of time? Do you believe these abilities substantially reduce carbon emission and the use of electricity when searching information?” and the gender of respondents, we noticed, in the Chi-Square Tests Table (Table 9) that the test results were significant χ2 [2] = 3.629, p = 0.163; thus, there is no statistically significant interdependency between the two variables.

Table 9.

Chi-Square 3.

3.1.3. Correlation between the Answers to Questions 3 and 7

By checking to see if there were significant differences between the subjects who believed that this information has an impact on those who use electronic sources of information and the declared time of daily internet use, we noticed that, out of the 227 subjects who believed that information has an impact on those who use electronic sources of information, the daily use of the internet is 4, namely 5 h a day (Table 10).

Table 10.

Cross-Tabulation 4.

According to the correlation between the answer to the question “Do you believe that the presented information has an impact on those who use the electronic sources of information” and the number of hours of daily internet use of the respondents, according to the Chi-Square Tests Table (Table 11), the results are significant χ2 [14] = 49.914, p = 0.00; thus, there is a statistically significant connection between the two variables.

Table 11.

Chi-Square 4.

It was statistically demonstrated that the presented information will have an impact on the informational behavior of students. They will access the internet for fewer hours daily and will improve their information skills in order to contribute to the sustainability of the environment.

By analyzing the statistical data, it was demonstrated that information received in regard to environmental sustainability, namely the fact that the quick access to information reduces the carbon footprint, has essentially modified the students’ behavior. This information is essential to develop the students’ ST. We believe that the transmission of this information can be best done through IL courses, as shown by the results of statistical research.

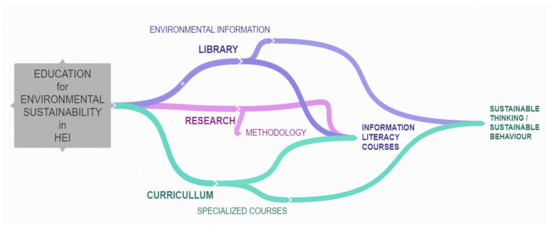

3.2. The Theoretic Map of Concepts

Starting from the premise that IL develops ST, we developed a Theoretical map of concepts thatdemonstrates the development of ST and the sustainable behaviors of students by including IL in all forms of education (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Theoretical map of concepts.

In creating this Theoretical map, we used the Extended Map of concepts and the Limited Map of concepts and articles adequate to this topic resulting from the STRING 2 search, as refined by STRING 3.

The connection between education for sustainability within HEI and ST, including the sustainable behavior of students, can be achieved by any of the three important aspects of education:

- (i).

- Specialized environmental protection classes and IL classes, which can contain necessary information; thus, it requires adequate curricula;

- (ii).

- The research activity and methods of research, which involve competence/skills that can be obtained/developed by IL; and

- (iii).

- Libraries, which offer specialized information in regard to environmental protection and can contribute, by IL, to obtaining/developing the skills needed for sustainable behavior and thinking.

We notice that IL can be considered the common line between these three aspects of education, which can complete the education for environmental sustainability in order to develop ST and determine sustainable behavior.

4. Discussion

Without a doubt, the role of HEI is to educate students and help develop their environmentally ST but also some skills/behaviors that will assist them in reaching the environmental sustainability requirements [1,2,3]. Over the past 40 years, the promotion of sustainable, pro-environmental behavior has been the primary goal of environmental education [36]. Although for years, the relationship between knowledge and behavior has been the focus of environmental studies [37], the current research explains the failure to promote pro-environmental behavior by increasing knowledge with a lack of a full understanding of the relationship between these two factors [36].

There are also critical opinions that show that the current education systems, instead of teaching the crucial skills to make sound and ethical decisions, reinforce unsustainable thinking and practices [15,16,35,38]. Therefore, the efforts to transform society have to focus on educators: building their understanding of sustainability and their ability to transform curriculum and wider learning opportunities [7,39].

Students’ education for a sustainable environment is generally achieved directly by (i) specialized courses; (ii) specific tasks like solving an air pollution problem [9] or preparing an integrated sustainability report for a large corporation [10]; (iii) research, because the teacher’s role is to bring things to the table for study and practice so that the students can give their own meaning to it [11] and because, by research, students develop competence for sustainable development [7,24]; or (iv) specialized information contained in libraries (printed information or databases) because libraries are the hub of campus life and can take the lead in sustainability issues [8], and students have recognized the institution’s library as an important facilitator of information sources on issues connected with the protection of the environment and sustainability [22].

We researched the existence of a connection between IL and the development of ST in students;thus we consider it an indirect means of education, by considering the main skills and competencies of IL courses.

The scientific research of specialty literature was performed in the Web of Science (WOS) database and required two research protocols [STRING 1 and STRING 2] and a refinement [STRING 3] determined by the fact that the results obtained by STRING 1 were reduced and the ones obtained by STRING 2, in order to be conclusive, had to be refined so as to be scientifically accurate between the years 2016 and 2020, which was achieved with STRING 3.

The analysis and interpretation of data, after STRING 1, generated two maps (Figure 1 and Figure 2) of concepts used in the researched specialty literature, maps that pointed out the interdependency of IL with education and environmental sustainability.

In order to develop a general model (Figure 4) through which we can demonstrate that IL can influence the development of ST and determine sustainable behaviors by influencing the most important aspects of education: curricula, research, and library. The obtained information was added, which resulted from applying STRING 3 adequate to this topic.

The statistical research was necessary in order to validate or invalidate the results of the scientometric study and was performed on a representative group of 336 students who participated in the IL course. Questions 3, 4, 5, and 6 of the questionnaire and the provided answers were analyzed in order to validate or invalidate the results of the scientometric research. We concluded that the answers validated the scientometric research, as the respondents believed that (i) the information which was presented has an impact on those who use electronic sources of information (67.86%, question 3); (ii) information research skills in the appropriate sources and in using a shorter period of time substantially reduces carbon emissions and the use of electricity needed for searching for information (74.25%, question 4); (iii) information literacy can determine ST (32.34% strongly believe this and 55.59% believe that it can determine ST in a significant manner, question 5); (iv) they will change their research information behavior by using the techniques learned in the IL class (79.64%, question 6).

The second objective of the statistical research, the correlation of answers of the respondents to questions 3 and 4 with the answers regarding the time of daily internet use, year of study, and gender of respondents show that

- -

- there is a connection between (i) the number of hours in which the respondents access the internet every day and the positive answers, namely that the information that was presented will have an impact on the informational behavior of students, and (ii) the number of respondents who believe that this information has an impact on those who use the electronic sources of information, depending on their year of study; and that

- -

- there are no significant differences between (i) the respondents who believe that this information has an impact on those who use electronic sources of information and the gender of respondents; nor (ii) between the respondents who believe that this information helps obtain searching skills and that these abilities substantially reduce the carbon emission and the use of electricity when searching for information and the gender of respondents.

However, there are some limitations of this research in regard to (i) the application of the questionnaire only at the level of an HEI and (ii) the number of students who participated.

5. Conclusions

This scientometric study pointed out the existence of a new possible direction of research regarding environmental sustainability and ST at the intersection of the three pillars of education: curricula, research, and library. The connection proved to be IL by introducing information on environmental issues. We specify that IL can be both in the form of specialized courses and in the form of modules included in other courses that use or refer to the search and research conducted in the online environment.

The statistical research confirms the scientometric study and validates the connection between IL and the development of ST.

The authors suggest the introduction of a module within the IL course in which the students are informed about the close connection between their research abilities and use of information skills and the reduction of the carbon print generated by the use of electronic resources.

The positive effect of the development of ST, gained through awareness of the importance of acquiring and using research skills, can be multiplied, in terms of reducing the carbon footprint, by applying sustainable behavior to other sources of CO2 production.

This opens a new way to reach the SDGs by identifying new information that can be subsequently introduced in different courses, not only those of IL, and that can have a positive impact on the development of ST and sustainable behavior. The development of ST represents a premise of creating an educated and responsible citizen in regard to environmental sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and C.S.R.; methodology, A.R. and C.S.R.; software, A.R.; validation, A.R., C.S.R. and C.M; formal analysis, A.R. and C.S.R.; investigation, A.R.; resources, C.S.R.; data curation, C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.R.; writing—review and editing, C.S.R.; visualization, A.R.; supervision, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Coronado, C.; Freijomil-Vázquez, C.; Fernández-Basanta, S.; Andina-Díaz, E.; Movilla-Fernández, M.J. Using photovoice to explore the impact on a student community after including cross-sectional content on environmental sustainability in a university subject: A case study. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Harmonizing ecological sustainability and higher education development: Wisdom from Chinese ancient education philosophy. Educ. Philos. Theory 2019, 51, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, W.M.; Henriksen, H.; Spengler, J.D. Universities as the engine of transformational sustainability toward delivering the sustainable development goals: “Living labs” for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barresi, P.A.; Focht, W.J.; Reiter, M.A.; Smardon, R.C.; Humphreys, M.; Reiter, K.D.; Kolmes, S.A. Revealing Complexity in Educating for Sustainability: An Update on the Work of the Roundtable on Environment and Sustainability. In Integrating Sustainability Thinking in Science and Engineering Curricula; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakopoulos, G.; Ntanos, S.; Asonitou, S. Investigating the environmental behavior of business and accounting university students. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCunn, L.J.; Bjornson, A.; Alexander, D. Teaching sustainability across curricula: Understanding faculty perspectives at Vancouver Island University. Curric. J. 2020, 31, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.O. Mapping out Students’ Opportunity to Learn about Sustainability across the Higher Education Curriculum. Innov. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, M.A.; Smith, B.J.; Buehler, M.A. Engagement of academic libraries and information science schools in creating curriculum for sustainability: An exploratory study. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2014, 40, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosronejad, M.; Reimann, P.; Markauskaite, L. ‘We are not going to educate people’: How students negotiate engineering identities during collaborative problem solving. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkowski, A.J.; Kowalczyk, W.; Ahrendsen, B.L.; Kowalski, R.; Majewski, E. Enhancing sustainability education through experiential learning of sustainability reporting. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1233–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Poeck, K.; Östman, L. The Risk and Potentiality of Engaging with Sustainability Problems in Education—A Pragmatist Teaching Approach. J. Philos. Educ. 2020, 54, 1003–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, K.; Paez, A. Student perceptions of reflection and the acquisition of higher-order thinking skills in a university sustainability course. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Cotano-Olivera, C. Driving private schools to go “green”: The case of Spanish and Italian religious schools. Teach. Theol. Relig. 2020, 23, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.O. Charting students’ exposure to promising practices of teaching about sustainability across the higher education curriculum. Teach. High. Educ. 2020, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, Z.A.; Zhang, Q.; Ou, J.; Saqib, K.A.; Majeed, S.; Razzaq, A. Education for sustainable development in Pakistani higher education institutions: An exploratory study of students’ and teachers’ perceptions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Agyeman, Y. Formation of a sustainable development ecosystem for Ghanaian universities. Int. Rev. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucco, C.; Ferranti, C. Developing critical thinking in online search. J. E-Learning Knowl. Soc. 2017, 13, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Library Association. Information Literacy—LibGuides at American Library Association. Available online: https://libguides.ala.org/InformationEvaluation/Infolit (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- Irving, C. National Information Literacy Framework (Scotland): Pioneering Work to Influence Policy Making or Tinkering at the Edges? Libr. Trends 2011, 60, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, T.; Trencheva, T.; Kurbanoğlu, S.; Doğan, G.; Horvat, A.; Boustany, J. A multinational study on copyright literacy competencies of LIS professionals. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2014, 492, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, T.; Eroğlu, Ş. Zenginleştirilmiş Kütüphanelerdeki Mevcut Durum ve Uygulamaların Analizi: Ankara’nın Çankaya İlçesindeki 12 Okulda Gerçekleştirilen Araştırmanın Sonuçları. Türk Kütüphaneciliği 2020, 34, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balog, K.P.; Siber, L. Law Students’ Information Literacy Skills and Attitudes Towards Environmental Protection and Environmental Legislation. Libri 2016, 66, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, E.J. Reflections on an Embedded Librarianship Approach: The Challenge of Developing Disciplinary Expertise in a New Subject Area. J. Aust. Libr. Inf. Assoc. 2019, 68, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W.; Van Petegem, P. The interrelations between competences for sustainable development and research competences. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 776–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelar, A.B.A.; da Silva-Oliveira, K.D.; da Silva Pereira, R. Education for advancing the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals: A systematic approach. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Steering Committee on Education for Sustainable Development. Economic Commission for Europe Committee on Environmental Policy United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Steering Committee on Education. Learning from Each Other: Achievements, Challenges and Ways Forward—Second Evaluation Report of the United Nations. 2011, 8, 1–7. Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/env/esd/6thMeetSC/Informal%20Documents/Paper%20No.%205%20Background%20Paper%20Panel%20Discussion.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2020).

- Deniz, D. Sustainable Thinking and Environmental Awareness through Design Education. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 34, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppelt, B. The Power of Sustainable Thinking: How to Create a Positive Future for the…—Bob Doppelt—Google Cărți. 2008. Available online: https://books.google.ro/books?id=9JsM73OTvc8C&printsec=frontcover&hl=ro#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Audouin, M.; de Wet, B. Sustainability thinking in environmental assessment. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, I.A.; Veeraghanta, S. Embedding information literacy within sustainability research: First year students’ perspectives. ASEE Annu. Conf. Expo. Conf. Proc. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A. Educating at scale: Sustainable library learning at the University of Melbourne. Libr. Manag. 2016, 37, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange Salvia, A.; Londero Brandli, L.; Leal Filho, W.; Gasparetto Rebelatto, B.; Reginatto, G. Energy sustainability in teaching and outreach initiatives and the contribution to the 2030 Agenda. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Lasuen, U.; Ortuzar Iragorri, M.A.; Diez, J.R. Towards energy transition at the Faculty of Education of Bilbao (UPV/EHU): Diagnosing community and building. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, K.R. Information Literacy for Students and Teachers in Indian Context. Pearl A J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2014, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.; Dierkes, P. Evaluating Three Dimensions of Environmental Knowledge and Their Impact on Behaviour. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 1347–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, M. From Knowledge to Action? Exploring the Relationships between Environmental Experiences, Learning, and Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J.; Erickson, J.S. Culture, Recognition, and the Negotiation of Difference: Some Thoughts on Cultural Competency in Planning Education. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2012, 32, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argento, D.; Einarson, D.; Mårtensson, L.; Persson, C.; Wendin, K.; Westergren, A. Integrating sustainability in higher education: A Swedish case. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).