Reconstructive Social Innovation Cycles in Women-Led Initiatives in Rural Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Empirical Background: Gender Equity and Social Innovation in Rural Areas

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Miqqut Program by Ilitaqsiniq-Nunavut Literacy Council (“Ilitaqsiniq-NLC”)

4.2. Women Farmers Social Cooperative—South Tyrol, Italy

4.3. Economic Empowerment of Women in Deir el Ahmar-Lebanon

4.4. Argan Co-Operative of Rural Women, Morocco

4.5. Radanska Ruža Social Enterprise, Serbia

4.6. Summary of the Findings from the Case Studies

5. Discussion

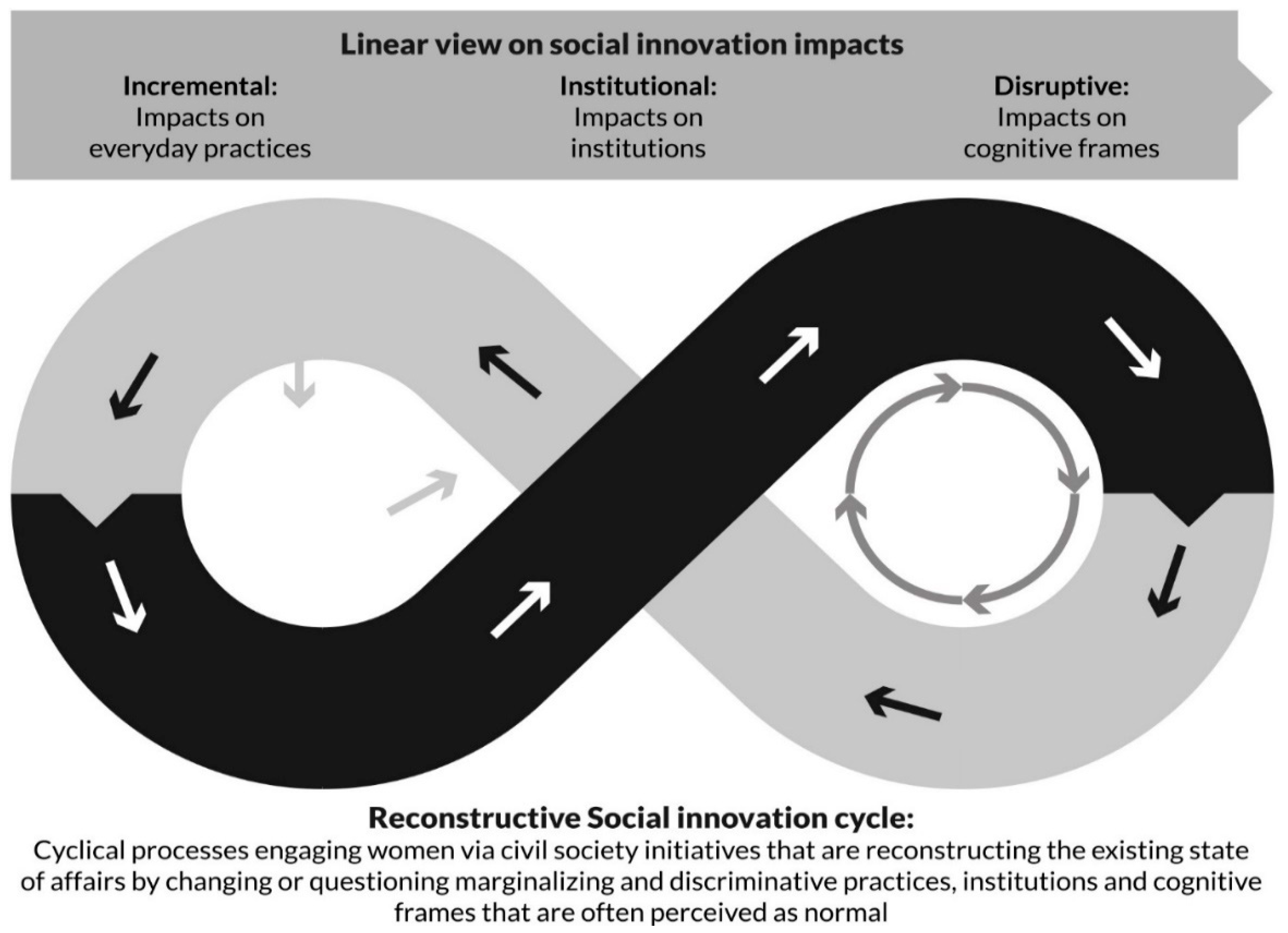

5.1. Intertwined Incremental, Institutional, and Disruptive Dimensions of Social Innovation

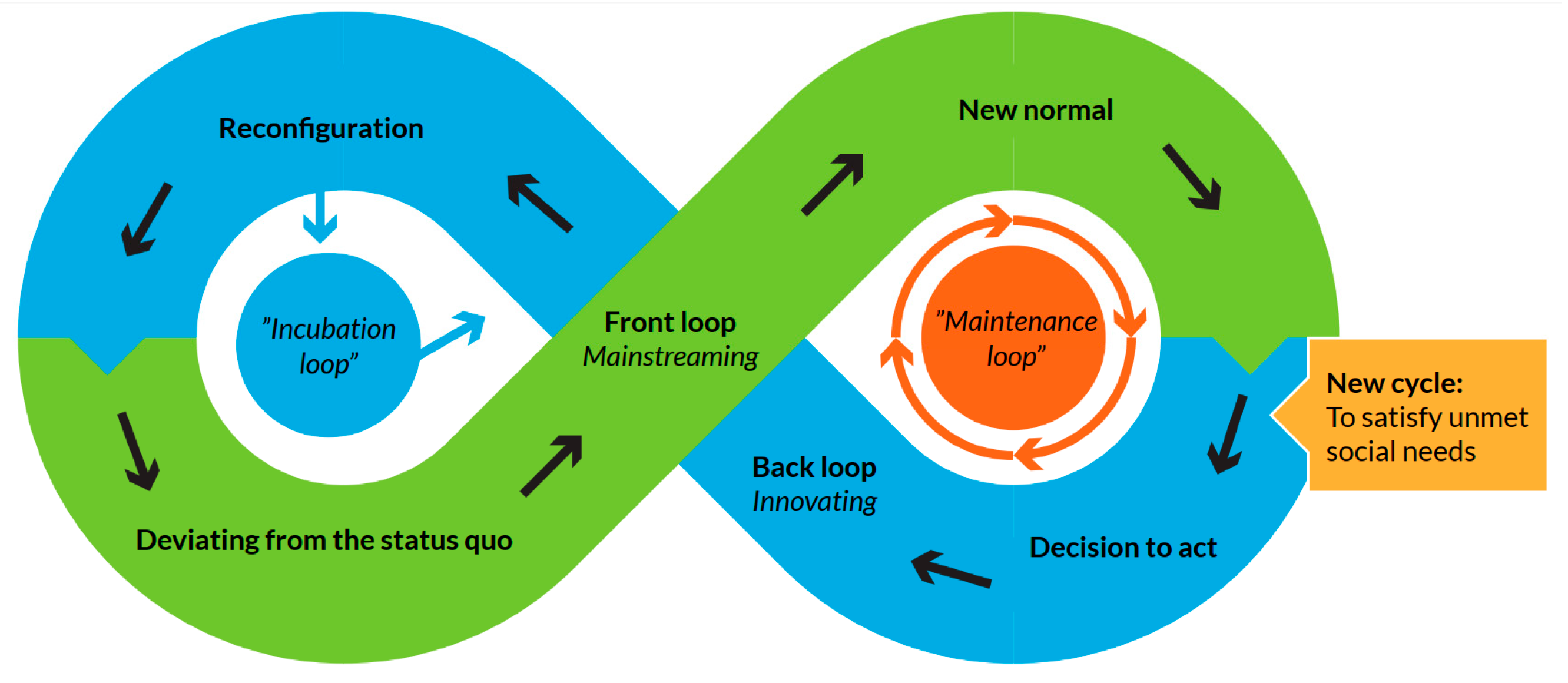

5.2. Reconstructive Social Innovation Cycles

5.2.1. Decisions to Act Leading to Reconfiguration

5.2.2. Deviating from the Status Quo Consisting of Discriminative Institutions and Norms

5.2.3. Impacts: New Normal

5.2.4. Incubation Loop and Maintenance Loop

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). What Does It Mean to Leave No One Behind? A UNDP Discussion Paper and Framework for Implementation. 2018. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/poverty-reduction/what-does-it-mean-to-leave-no-one-behind-.html (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Nhamo, G.; Muchuru, S.; Nhamo, S. Women’s needs in new global sustainable development policy agendas. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). UN SDG 5. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Gender and Sustainable Development: Maximising the Economic, Social and Environmental Role of Women. 2008. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/social/40881538.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Brydon, L.; Chant, S.H. Women in the Third World: Gender Issues in Rural and Urban Areas; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, C.E. Gendered Fields: Rural Women, Agriculture and Environment. In Rural Studies Series; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, M.; Forsberg, L.; Karlberg, H. Gendered social innovation—A theoretical lens for analysing structural transformation in organisations and society. Int. J. Soc. Entrep. Innov. 2015, 3, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguirre, M.V.; Ruelas, G.C.; de La Torre, C.G. Women empowerment through social innovation in indigenous social enterprises. RAM. Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2016, 17, 164–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestripieri, L. Does Social Innovation Reduce the Economic Marginalization of Women? Insights from the Case of Italian Solidarity Purchasing Groups. J. Soc. Entrep. 2017, 8, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.S.H.; Muhamad, M.; Jalil, M. Man Empowering Rural Women Entrepreneurs through Social Innovation Model. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Aff. (IJBEA) 2018, 3, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Mehmood, A.; MacCallum, D.; Leubolt, B. Social Innovation as a Trigger for Transformations. In The Role of Research; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Polman, N.; Slee, W.; Kluvánková, T.; Dijkshoorn, M.; Nijnik, M.; Gezik, V.; Soma, K. Classification of Social Innovations for Marginalized Rural Areas. H2020-SIMRA Deliverable 2.1. 2017. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/D2.1-Classification-of-SI-for-MRAs-in-the-target-region.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2017).

- Nijnik, M.; Kluvankova, T.; Nijnik, A.; Kopiy, S.; Melnykovych, M.; Sarkki, S.; Barlagne, C.; Brnkalakova, S.; Kopiy, L.; Fizyk, I.; et al. Is there a scope for social innovation in Ukrainian forestry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluvankova, T.; Nijnik, M.; Spacek, M.; Sarkki, S.; Lukesch, R.; Perlik, M.; Melnykovych, M.; Valero, D.; Brnkalakova, S. Social innovation for sustainability transformation and its diverging development paths in marginalised rural areas. Sociol. Rural. 2021, 12337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.; Murdock, A. (Eds.) Social Innovation: Blurring Boundaries to Reconfigure Markets; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin, A.M.; Stangl, L.M. The Social Innovation Continuum: Towards Addressing Definitional Ambiguity. 2013. Available online: http://mro.massey.ac.nz/ (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Butler, J. Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre J. 1988, 40, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Fortunes of Feminism: From State-Managed Capitalism to Neoliberal Crisis; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1844679843. [Google Scholar]

- Sabsay, L. Nancy Fraser: Fortunes of Feminism: From State-Managed Capitalism to Neoliberal Crisis. Fem. Leg. Stud. 2014, 22, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleutério, R.P.; van Amstel, F. Matters of Care in Designing a Feminist Coalition. In ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 2nd ed.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Osei, C.D.; Zhuang, J. Rural Poverty Alleviation Strategies and Social Capital Link: The Mediation Role of Women Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 215824402092550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antelo, M.Á.P.; González, R.C.L. The role of European fisheries funds for innovation and regional development in Galicia (Spain). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 2394–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.R.; Mehmood, A. Reproductive health services: “Business-in-a-Box” as a model social innovation. Dev. Pract. 2019, 29, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnecke, T. Social Innovation, Gender, and Technology: Bridging the Resource Gap. J. Econ. Issues 2017, 51, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergaki, P.; Partalidou, M.; Iakovidou, O. Women’s agricultural co-operatives in Greece: A comprehensive review and swot analysis. J. Dev. Entrep. 2015, 20, S1084946715500028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafun, L.; Säävälä, M. Domestic violence made public: A case study of the use of alternative dispute resolution among underprivileged women in Bangladesh. Contemp. South Asia 2014, 22, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, T.O. Gender and Diversity as impetus for social innovations in rural development—A neo-institutional analysis of LEADER. Osterreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 2020, 45, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. Facts and Figures: Economic Empowerment. 2018. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/facts-and-figures (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rural Women: Striving for Gender-Transformative Impacts. 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i8222e.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- UN Women. Turning Promises into Action: Gender Equality in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2018. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2018/2/gender-equality-in-the-2030-agenda-for-sustainable-development-2018 (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Bock, B.; Shortall, S. (Eds.) Rural Gender Relations: Issues and Case Studies. In Rural Gender Relations; CABI Publishing Series; CABI Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2006; p. 374. [Google Scholar]

- Gramm, V.; Torre, C.D.; Membretti, A. Farms in Progress-Providing Childcare Services as a Means of Empowering Women Farmers in South Tyrol, Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živojinović, I.; Ludvig, A.; Hogl, K. Social Innovation to Sustain Rural Communities: Overcoming Institutional Challenges in Serbia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.; Mukherjee, A. No Empowerment without Rights, No Rights without Politics: Gender-equality, MDGs and the post-2015 Development Agenda. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2014, 15, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S. The 2030 Agenda: Challenges of implementation to attain gender equality and women’s rights. Gend. Dev. 2016, 24, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, T.A.; Prasad, A. Entrepreneurship amid concurrent institutional constraints in less developed countries. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 934–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, J. From Hegemonic Masculinity to the Hegemony of Men. Fem. Theory 2004, 5, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfeir, P.R.; Karam, B.; Boutchakdjian, L.; Ayadi, J.L. Coop: The Story of Women Thriving for a Better Future. SIMRA Social Innovation Action “Economic Empowerment of Women in Deir El Ahmar (North Bekaa, Lebanon; led by SEEDS-Int)”. 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XATxMLtgc5Q (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas. Social Innovation in Marginalized Rural Areas. 2020. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/ (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Alkhaled, S.; Jack, S.L.; Binnion, J. The Growing Club: Social Innovation and Women as Agents of Change in Lancashire and Cumbria, North West England, UK. SIMRA Social Innovation Action “Coaching Socially Disadvantaged Women into Developing Successful Small Business Initiatives in Lancashire and Cumbria (Lancaster, UK; Led by Lancaster University)”. 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DZ21Wwys4MU (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Dalla Torre, C.; Gramm, V.; Lolini, M.; Ravazzoli, E. Analytical Case Studies (Case Study Type A) Learning, Growing, Living with Women Farmers—South Tyrol, Italy (Led by EURAC); Unpublished Internal Report; Report 5.4d; Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA): Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2019; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Chorti, H.; Labidi, A.; Boulajfene, H.; Hayder, M.; Melnykovych, M.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Bengoumi, M. Argan Co-Operative of Rural Women in Morocco; Unpublished Internal Report; Report 5.4o; Analytical-Informational Case Studies (Type C) Led by FAOSNE; Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA): Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2019; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Labidi, A.; Boulajfene, H.; Hayder, M.; Melnykovych, M.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Bengoumi, M. Valorisation of Non-Wood Forest Products through the Market Analysis and Development (MAD) Approach in Tunisia; Unpublished Internal Report; Report 5.4p; Analytical-Informational Case Studies (Type C) Led by FAOSNE; Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA): Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2019; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Mifsud, E.G.; Melnykovych, M.; Govigli, V.M.; Alkhaled, S.; Arnesen, T.; Barlagne, C.; Bjerck, M.; Burlando, C.; Jack, S.; Blanco, C.R.F.; et al. Report on Lessons Learned from Innovation Actions in Marginalised Rural Areas. 2019. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/D7.3_Lessons-Learnt-from-Innovation-Actions-in-Marginalised-Rural-Areas_compressed.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Torres, A.N. Female Leadership in Rural Areas. In A Social Innovation Review, Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Social, Business, and Academic Leadership (ICSBAL 2019), Prague, Czech Republic, 21–22 June 2019; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, C.D.; Ravazzoli, E.; Dekker, M.D.; Polman, N.; Melnykovych, M.; Pisani, E.; Gori, F.; da Re, R.; Vicentini, K.; Secco, L. The Role of Agency in the Emergence and Development of Social Innovations in Rural Areas. Analysis of Two Cases of Social Farming in Italy and The Netherlands. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Council. Activist to Entrepreneur: The Role of Social Enterprise in Supporting Women’s Empowerment. 2017. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/social_enterprise_and_womens_empowerment_july.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Franic, R.; Kovacicek, T. The Professional Status of Rural Women in the EU. Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs Directorate General for Internal Policies of the Union; PE 608.868. 2019. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- UN Women. Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals. The Gender Snapshot. 2019. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2019/09/progress-on-the-sustainable-development-goals-the-gender-snapshot-2019#view (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative (WE-FI). We-Fi Annual Report 2019. 2020. Available online: https://we-fi.org/ (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Govigli, V.M.; Alkhaled, S.; Arnesen, T.; Barlagne, C.; Bjerck, M.; Burlando, C.; Melnykovych, M.; Blanco, C.R.F.; Sfeir, P.; Mifsud, E.G. Testing a Framework to Co-Construct Social Innovation Actions: Insights from Seven Marginalized Rural Areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercher, N.; Barlagne, C.; Hewitt, R.; Nijnik, M.; Esparcia, J. Narratives of social innovation. A comparative analysis of community-led initiatives in Scotland and Spain. Sociol. Rural. 2020, 12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, M. Abductive reasoning and qualitative research. Nurs. Philos. 2012, 13, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavory, I.; Timmermans, S. Abductive Analysis: Theorizing Qualitative Research; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Nijnik, M.; Secco, L.; Miller, D.; Melnykovych, M. Can social innovation make a difference to forest-dependent communities? For. Policy Econ. 2019, 100, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Tavory, I. Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis. Sociol. Theory 2012, 30, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. 2019. Available online: https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Final_Report_Vol_1a-1.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Tester, F. Colonial Challenges and Recovery in the Eastern Arctic. In Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: What Inuit Have Always Known to Be True; Karetak, J., Tester, F., Tagalik, S., Eds.; Fernwood Publishing: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2017; Chapter 1; pp. 20–36. ISBN 978-1552669914. [Google Scholar]

- Kral, M.J. Suicide and Suicide Prevention among Inuit in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tester, F.; Kulchyski, P. Tammarniit (Mistakes): Inuit Relocation in the Eastern Arctic, 1939–63; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1994; ISBN 978-0774804943. [Google Scholar]

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada (Pauktuutit). National Strategy to Prevent Abuse in Inuit Communities and Sharing Wisdom: A Guide to the National Strategy. 2006. Available online: https://www.pauktuutit.ca/wp-content/uploads/InuitStrategy_e.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Rotenberg, C. Police-Reported Violent Crimes against Young Women and Girls in Canada’s Provincial North and Territories 2017. In Statistics Canada; Catalogue no. 85-002-X; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Billson, J.M.; Mancini, K. Inuit Women—Their Powerful Spirit in a Century of Change; Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc.: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0742535978. [Google Scholar]

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada (Pauktuutit). Strategy to Engage Inuit Women in Economic Participation. 2016. Available online: https://www.pauktuutit.ca/wp-content/uploads/Engaging_Inuit_Women_in_Economic_Participation.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Arriagada, P. First Nations, Métis and Inuit Women. In Women in Canada: A Gender-Based Statistical Report; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tulloch, S.; Kusugak, A.; Uluqsi, G.; Pilakapsi, Q.; Chenier, C.; Ziegler, A.; Crockatt, K. Stitching Together Literacy, Culture & Well-Being: The Potential of Non-Formal Learning Programs. North Public Aff. 2013, 6, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ilitaqsiniq-Nunavut Literacy Council (Ilitaqsiniq-NLC). The Miqqut Project—Joining Literacy, Culture and Well-Being through Non-Formal Learning in Nunavut: Summary of the Research Report. 2013. Available online: https://fimesip.ca/project/miqqut-project/ (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Auditor General of Canada. Education in Nunavut: November 2013 Report of the Auditor General of Canada. 2013. Available online: http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/nun_201311_e_38772.html (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Pucci, M. Nunavut Races to Fill Dozens of Teaching Spots as School Year Begins. 2018. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/nunavut-teacher-shortage-1.4791025 (accessed on 20 August 2018).

- Minogue, S. Facing Inuit Teacher Shortages, Nunavut Education Minister Wants to Move Deadlines on Bilingual Instruction. 2017. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/bill-37-nunavut-education-act-language-protection-act-1.4020945 (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Kangas, T.S.; Phillipson, R.; Dunbar, R. Is Nunavut Education Criminally Inadequate? An Analysis of Current Policies for Inuktut and English in Education, International and National Law: Linguistic and Cultural Genocide and Crimes against Humanity. 2019. Available online: https://www.tunngavik.com/news/is-nunavut-education-criminally-inadequate/ (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Kusugak, A. Miqqut. First Nations, Inuit and Métis Essential Skills Inventory Project (FIMESIP). Available online: https://fimesip.ca/project/miqqut-project/ (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Tulloch, S.; Kusugak, A.; Chenier, C.; Pilakapsi, Q.; Uluqsi, G.; Walton, F. Transformational Bilingual Learning: Re-Engaging Marginalized Learners through Language, Culture, Community, and Identity. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 2017, 73, 438–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.H. Conflict and Compromise among Borderline Identities in Northern Italy. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2000, 91, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matscher, A.; Larcher, M.; Vogel, S.; Maurer, O. Self-perception of farming women in South Tyrol. Jahrb. Osterr. Ges. Agrar. 2009, 18, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Matscher, A.; Larcher, M.; Vogel, S.; Maurer, O. Zwischen Tradition und Moderne: Das Selbstbild der Südtiroler Bäuerinnen. Z. Agrargesch. Agrarsoziol. 2008, 2, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Autonomous Province of South Tyrol Provincial Statistics Institute—ASTAT. South Tyrol in Figures 2016. Available online: https://astat.provinz.bz.it/downloads/Siz_2016-eng(1).pdf (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Annes, A.; Wright, W. ‘Creating a room of one’s own’: French farmwomen, agritourism and the pursuit of empowerment. Women Stud. Int. Forum 2015, 53, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkki, S.; Ficko, A.; Miller, D.; Barlagne, C.; Melnykovych, M.; Jokinen, M.; Soloviy, I.; Nijnik, M. Human values as catalysts and consequences of social innovations. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 104, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S.; Gunderson, L.H. Resilience and Adaptive cycles. In Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems; Gunderson, L.H., Holling, C.S., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- Salvia, R.; Quaranta, G. Adaptive Cycle as a Tool to Select Resilient Patterns of Rural Development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 11114–11138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resilience Alliance. Assessing Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems: Workbook for Practitioners. Version 2.0.. 2010. Available online: https://www.resalliance.org/ (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Biggs, R.; Westley, F.R.; Carpenter, S.R. Navigating the back loop: Fostering social innovation and transformation in ecosystem management. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.-L.; Westley, F.R.; Tjornbo, O.; Holroyd, C. The Loop, the Lens, and the Lesson: Using Resilience Theory to Examine Public Policy and Social Innovation. In Social Innovation; Nicholls, A., Murdock, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Name of the Social Innovation | “Miqqut” Programs by the Ilitaqsiniq Nunavut Literacy Council (Ilitaqsiniq-NLC) | “Learning, Growing, Living with Women Farmers” Social Cooperative | “Jana Al Ayadi” Cooperative Aiming for Economic Empowerment of Women | Afoulki Cooperative of Rural Women in MOROCCO | Radanska Ruža Social Enterprise Employing Marginalized Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Nunavut, Canada | South Tyrol, Italy | Deir El Ahmar, Lebanon | South Morocco, Morocco | Municipality of Lebane, South Serbia |

| Key challenges for rural women | Intergenerational and socio-psychological traumas from colonial developments, which are connected to losses of culture and tradition, identity confusion, domestic and other types of violence, addictions and breaking down of families. Lack of support with education and childcare, self-confidence issues, lack of housing, geographical isolation, sexism in male-dominated work sectors. | Economic dependency of women on male members in farm families, gendered roles on farms and unpaid work, lack of professionalization and of a specific role of women on farms, resulting in women taking care of many different tasks from child raising to household work, which do not entail strategic decision-making powers relating to family businesses, and patriarchal value structures. | Low levels of literacy, unemployment, male dominated businesses, patriarchal value structures and gender roles, and lack of recognition of women’s agency. | High unemployment and migration rates, poverty, low levels of literacy, subsistence family farming and non-wood forest products as a source of income. | Strong patriarchal gender roles and severe unemployment especially of women |

| Social innovation activities | Not-for-profit organization providing culturally relevant non-formal learning programs (e.g., in sewing) with embedded literacy and essential skills training | Social cooperative providing training program and organization of childcare service provision by women farmers on their farm according to nature pedagogy values. | Women led cooperative specialized in the production and marketing of local authentic products, employing local women. | Rural women’s cooperative created with the aim to improve the livelihoods of rural women through the valorization and commercialization of the Argan oil. | Social enterprise producing traditional agricultural added-value products employing marginalized women |

| Temporal scale | 2011 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2015 |

| Empirical materials | Participant observation in 2018–2019. Semi-structured interviews on this topic (n = 3), and on local women’s lives from various different perspectives (n = 50). Literature review (scientific literature, public/policy reports, national statistics, and grey literature). Social media screening | Semi-structured interviews (n = 11). Focus group (n = 1), Survey (n = 21). Field observations. Literature review (see [32,46,51]). Workshop for discussing of results from previous empirical work. | Field observations (regularly in the period 2017–2019) Unstructured interviews with members of the cooperative (n = 3) Participatory video; Workshop with members of the cooperative, local authorities and other stakeholders | Structured Interviews (n = 5) semi-structured interview (n = 5) | Semi-structured interviews (n = 4). Document analysis focusing on grey literature. Media screening |

| The Social Innovation | Strengths | Weaknesses | Unique Aspects |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Miqqut” programs by the Ilitaqsiniq Nunavut Literacy Council (Ilitaqsiniq-NLC) | Opening opportunities for rural women to overcome marginalizing institutional settings in education and enhancing employment opportunities. | Initiatives not self-sufficient, but dependent on project-based funding | Connecting modern literacy with reviving cultural traditions to empower marginalized women and enhance intergenerational connectivity. Monitoring the impacts of the programs regularly |

| “Learning, growing, living with women farmers” social cooperative | Initiating the process of policy-making on social agriculture in the region; empowering women farmers in the decision-making process of the family farm, as their activity becomes part of the business strategy; increasing their awareness of doing a visible and valued job for the community | In some cases, women farmers are responsible for housekeeping, farming tasks and caring for their own children in addition to their new entrepreneurial activity. The case can be considered a clear example of the ongoing tension between farming tradition and modernization in mountain territories | Changing gender roles in decision-making processes at the micro level (farm), at the meso level (the community) and the provincial level |

| “Jana Al Ayadi” cooperative aiming for economic empowerment of women | Creating successful business employing marginalized women by enterprise producing and marketing agro-food products despite strong patriarchal gender roles | The success in the home village of the cooperative has been demonstrated, but in adjacent areas, social boundaries of male dominated markets and patriarchal cognitive frames remain | Extension of the business by the cooperative enabled smallholder producers to gain a fair space for marketing their products and connecting with the consumers, improve visibility and boost revenues |

| Afoulki cooperative of rural women in Morocco | Improving the living conditions of women by providing an enabling environment to gain a personal income and training opportunities, autonomy, and independence | Women are still mainly unpaid domestic workers and self-employed in subsistence farming | In 2018, the cooperative enlarged and became an umbrella network, for several other small cooperatives |

| Radanska Ruža social enterprise employing marginalized women | It targets especially disadvantaged and marginalized women, who find not only work and income at Radanska Ruža, but also a particularly appreciative social environment. | The initiative may be vulnerable due to high reliance on individual key actor | During an unexpected crisis, several crowdfunding campaigns were organized enabling continuance of the social enterprise |

| Cross-case findings |

| ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarkki, S.; Dalla Torre, C.; Fransala, J.; Živojinović, I.; Ludvig, A.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Melnykovych, M.; Sfeir, P.R.; Arbia, L.; Bengoumi, M.; et al. Reconstructive Social Innovation Cycles in Women-Led Initiatives in Rural Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031231

Sarkki S, Dalla Torre C, Fransala J, Živojinović I, Ludvig A, Górriz-Mifsud E, Melnykovych M, Sfeir PR, Arbia L, Bengoumi M, et al. Reconstructive Social Innovation Cycles in Women-Led Initiatives in Rural Areas. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031231

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarkki, Simo, Cristina Dalla Torre, Jasmiini Fransala, Ivana Živojinović, Alice Ludvig, Elena Górriz-Mifsud, Mariana Melnykovych, Patricia R. Sfeir, Labidi Arbia, Mohammed Bengoumi, and et al. 2021. "Reconstructive Social Innovation Cycles in Women-Led Initiatives in Rural Areas" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031231

APA StyleSarkki, S., Dalla Torre, C., Fransala, J., Živojinović, I., Ludvig, A., Górriz-Mifsud, E., Melnykovych, M., Sfeir, P. R., Arbia, L., Bengoumi, M., Chorti, H., Gramm, V., López Marco, L., Ravazzoli, E., & Nijnik, M. (2021). Reconstructive Social Innovation Cycles in Women-Led Initiatives in Rural Areas. Sustainability, 13(3), 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031231