Is an Appeal Enough? The Limited Impact of Financial, Environmental, and Communal Appeals in Promoting Involvement in Community Environmental Initiatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

Current Research

2. Study 1

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Procedure, Participants, and Design

2.1.2. Measures

2.2. Results

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Procedure, Participants, and Design

3.1.2. Measures

3.2. Results and Discussion

4. Study 3

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Procedure, Participants, and Design

4.1.2. Measures

4.2. Results and Discussion

5. Study 4

5.1. Method

5.1.1. Procedure and Sample

5.1.2. Measures

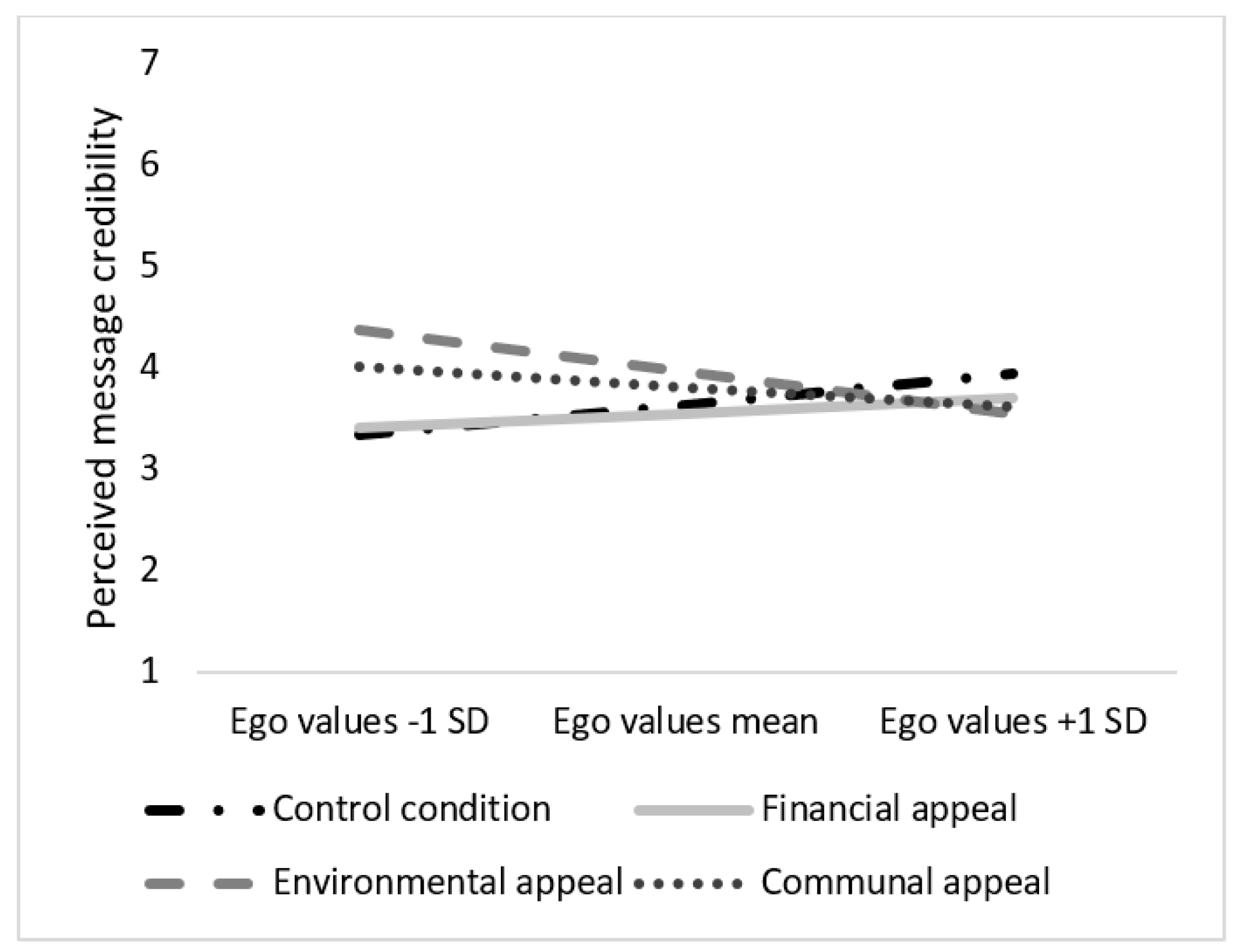

5.2. Results and Discussion

6. General Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Flyer Manipulations Used in Studies 1–3

Appendix A.1. Study 1

Appendix A.2. Study 2

Appendix A.3. Study 3

Appendix B. Comparative Overview of Measures across Studies

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | Study 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Financial, environmental, communal flyer appeal | Environmental, communal, combined flyer appeal | Financial, environmental, communal flyer appeal plus control (no appeal) condition | - |

| Measures | ||||

| Rated appeal emphasis | To what extent are the following aspects emphasised in the flyer? | |||

| (1 = not emphasised at all, 7 = very strongly emphasised) | ||||

| Financial | - Saving money (for example saving money for heating, investments in sustainable energy, increasing the value of the home, subsidies) | |||

| Environmental | - Environmental protection (for example reducing CO2 emissions, being green, protecting the environment) | |||

| Communal | - Sense of community (for example, doing activities together with other community members, meeting other community members, learning from neighbours) | |||

| Membership ratio | Number of initiative members/number of households in the neighbourhood | |||

| Interest to join | What do you think about the flyer? | Please answer the following questions on a scale from 1 to 7 | Please answer the following questions on a scale from 1 to 7 | |

| (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree) | (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree) | (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree) | ||

| - I would like to receive more information on the Movement Against Food Waste | - I would like to receive more information on the Good Food Student Initiative | - I would like to receive more information on the Clothes Swap Initiative | ||

| - I would like to become a member of the Movement Against Food Waste | - I am interested in joining the Good Food Student Initiative | - I am interested in joining the Clothes Swap Initiative | ||

| - I am interested in the Movement Against Food Waste | - I am interested in the Good Food Student Initiative | - I am interested in the Clothes Swap Initiative | ||

| - I would like to attend a meeting to get more information on the Movement Against Food Waste | - I am interested in attending a meeting of the Good Food Student Initiative | - I am interested in joining a meeting of the Clothes Swap Initiative and try swapping clothes myself | ||

| - I am interested in checking out the website or social media accounts of the Good Food Student Initiative | - I plan to check out the website or social media accounts of the Clothes Swap Initiative | |||

| - I intend to take part in the Movement Against Food Waste in the future | - I intend to join the Good Food Student Initiative | |||

| Behavioural DV | Choice to provide an email address (yes/no) | Choice to take a flyer (yes/no) | ||

| Perceived message quality | What do you think about the flyer? | Please answer the following questions on a scale from 1 to 7 | Please answer the following questions on a scale from 1 to 7 | |

| (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree) | (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree) | (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree) | ||

| - I find the information on the flyer convincing | - I find the message of the flyer convincing | - I find the information on the flyer convincing | ||

| - The message of the flyer is credible | - The message of the flyer is credible | - The information on the flyer is credible | ||

| - I find the message on the flyer inspiring | - I find the flyer inspiring | - I find the flyer inspiring | ||

| - I find the flyer appealing | - I find the information on the flyer appealing | |||

| Beliefs | To what extent do you think the initiative would… | |||

| (1 = not at all, 7 = very much) | ||||

| Financial | save you money | |||

| give you clothes for free | ||||

| Environmental | benefit the environment | |||

| reduce energy use and waste and save water | ||||

| Communal | bring students together | |||

| connect you with fellow students | ||||

| Environmental self-identity | Please answer the following questions on a scale from 1 to 7 | Please answer the following questions on a scale from 1 to 7 | ||

| (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree) | (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree) | |||

| - Acting pro-environmentally is an important part of who I am | - Acting pro-environmentally is an important part of who I am | |||

| - I am the type of person who acts pro-environmentally | - I am the type of person who acts pro-environmentally | |||

| - I see myself as an environmentally-friendly person | - I see myself as an environmentally-friendly person | |||

| Communal self-identity | - Being a student at the (name of university) is an important part of who I am | |||

| - I am the type of person who is a (name of university) student | ||||

| - I see myself as a (name of university) student | ||||

| Identification with students | - I identify with students at (name of university) | |||

| - I feel committed to students of (name of university) | ||||

| - I am glad to be a (name of university) student | ||||

| - Being a student at (name of university) is an important part of how I see myself | ||||

| Financial self-identity | - Being responsible about money is an important part of who I am | |||

| - I am the type of person who is responsible about their money | ||||

| - I see myself as someone who is responsible about their money | ||||

| Altruistic values | Could you please rate how important each value is for you AS A GUIDING PRINCIPLE IN YOUR LIFE? | |||

| (-1 = opposed to my values, 0 = not important at all, 1–5 = important, 6 = very important, 7 = of supreme importance) | ||||

| - EQUALITY: equal opportunity for all | ||||

| - A WORLD AT PEACE: free of war and conflict | ||||

| - SOCIAL JUSTICE: correcting injustice, care for the weak | ||||

| - HELPFUL: working for the welfare of others | ||||

| Biospheric values | - RESPECTING THE EARTH: harmony with other species | |||

| - UNITY WITH NATURE: fitting into nature | ||||

| - PROTECTING THE ENVIRONMENT: preserving nature | ||||

| - PREVENTING POLLUTION: protecting natural resources | ||||

| Egoistic values | - SOCIAL POWER: control over others, dominance | |||

| - WEALTH: material possessions, money | ||||

| - AUTHORITY: the right to lead or command | ||||

| - INFLUENTIAL: having an impact on people and events | ||||

| - AMBITIOUS: hard-working, aspiring | ||||

| Hedonic values | - PLEASURE: joy, gratification of desires | |||

| - ENJOYING LIFE: enjoying food, sex, leisure, etc. | ||||

| - SELF-INDULGENT: doing pleasant things |

Appendix C. Overview of Findings for Studies 1–3

| Descriptive Statistics per Experimental Condition | Inferential Statistics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial | Environmental | Communal | Combined env/com | Control | ANOVA | ||||||||

| Study 1 | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | df | p |

| Interest to join | 3.41 | 1.33 | 3.46 | 1.28 | 3.57 | 1.42 | 0.26 | 2, 228 | 0.772 | ||||

| Perceived message quality | 3.31 a | 1.02 | 3.95 b | 1.14 | 3.72 b | 1.19 | 6.74 | 2, 228 | 0.001 | ||||

| Request for more information | 34% | 40% | 37% | χ = 0.62 | 2 | <0.733 | |||||||

| Study 2 | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | df | p |

| Interest to join | 4.52 | 1.49 | 4.15 | 1.45 | 4.37 | 1.50 | 1.31 | 2, 247 | 0.272 | ||||

| Choice to take flyer | 52% | 48% | 60% | χ = 2.45 | 2 | 0.293 | |||||||

| Perceived message quality | 4.47 | 1.31 | 4.75 | 1.03 | 4.64 | 1.21 | 0.21 | 2, 247 | 0.809 | ||||

| Study 3 | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | df | p |

| Interest to join | 3.78 | 1.27 | 3.71 | 1.75 | 4.12 | 1.54 | 3.87 | 1.63 | 0.40 | 3, 120 | 0.751 | ||

| Perceived message quality | 3.63 | 1.03 | 3.88 | 1.35 | 3.82 | 1.24 | 3.61 | 1.29 | 0.35 | 3, 120 | 0.787 | ||

| Belief: financial | 4.95 | 1.21 | 4.94 | 1.51 | 5.50 | 0.95 | 5.41 | 1.11 | 1.81 | 3, 119 | 0.150 | ||

| Belief: environmental | 5.25 | 1.03 | 4.69 | 1.70 | 5.57 | 1.42 | 5.31 | 1.27 | 4.28 | 3, 119 | 0.087 | ||

| Belief: communal | 4.67 | 0.97 | 4.84 | 1.50 | 4.43 | 1.35 | 4.97 | 0.97 | 1.65 | 3, 119 | 0.381 | ||

References

- An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Middlemiss, L.; Parrish, B.D. Building capacity for low-carbon communities: The role of grassroots initiatives. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7559–7566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Haxeltine, A. Growing grassroots innovations: Exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2012, 30, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jans, L. Changing environmental behaviour from the bottom up: The formation of pro-environmental social identities. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, I.; Hopkins, R.; Wilson, G. Some things old, some things new: The spatial representations and politics of change of the peak oil relocalisation movement. Geoforum 2010, 41, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloot, D.; Jans, L.; Steg, L. The potential of environmental community initiatives—A social psychological perspective. In Outlooks on Applying Environmental Psychology Research; Römpke, A., Reese, G., Fritsche, I., Wiersbinski, N., Mues, A., Eds.; Bundesamt für Naturschutz: Bonn, Germany, 2017; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Middlemiss, L. The effects of community-based action for sustainability on participants’ lifestyles. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloot, D.; Jans, L.; Steg, L. Can community energy initiatives motivate sustainable energy behaviours? The role of initiative involvement and personal pro-environmental motivation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomberg, E.; McEwen, N. Mobilizing community energy. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T. Altruism, self-interest and energy consumption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 1654–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Köpetz, C.; Bélanger, J.J.; Chun, W.Y.; Orehek, E.; Fishbach, A. Features of Multifinality. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 17, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloot, D.; Jans, L.; Steg, L. In it for the money, the environment, or the community? Motives for being involved in community energy initiatives. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 57, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóci, G.; Vasileiadou, E. “Let’s do it ourselves” Individual motivations for investing renewables at community level. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 49, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Steg, L. Making small numbers count: Environmental and financial feedback in promoting eco-driving behaviours. J. Consum. Policy 2014, 37, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T. Environmental value. In Oxford Handbook of Values; Brosch, T., Sander, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 329–349. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L. Values, norms, and intrinsic motivation to act proenvironmentally. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Strategies for promoting proenvironmental behavior. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. A behavioral model of rational choice. Q. J. Econ. 1955, 69, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.T. The norm of self-interest. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duurzaam Oss Buurkracht: Besparen Met Eigen Buurt. Available online: https://www.duurzaamoss.nl/initiatieven/e530-besparen-met-eigen-buurt/ (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Bolderdijk, J.W.; Steg, L.; Geller, E.S.; Lehman, P.K.; Postmes, T. Comparing the effectiveness of monetary versus moral motives in environmental campaigning. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.; Fischlein, M.; Asensio, O. Information strategies and energy conservation behavior: A meta-analysis of experimental studies from 1975 to 2012. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.; Bruine de Bruin, W.; Fischhoff, B.; Lave, L. Advertising energy saving programs: The potential environmental cost of emphasizing monetary savings. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2015, 21, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, O.I.; Delmas, M.A. Nonprice incentives and energy conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S.M.; High-Pippert, A. From private lives to collective action: Recruitment and participation incentives for a community energy program. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7567–7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, E.; Johnson, M.; Robinson, S.; Vadovics, E.; Saastamoinen, M. Low-carbon communities as a context for individual behavioural change. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7586–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, B.H.; Hartwick, J.; Warshaw, P.R. The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edinger-Schons, L.M.; Sipilä, J.; Sen, S.; Mende, G.; Wieseke, J. Are two reasons better than one? The role of appeal type in consumer responses to sustainable products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2018, 28, 644–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broek, K.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Steg, L. Individual differences in values determine the relative persuasiveness of biospheric, economic and combined appeals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Hansla, A.; Heiling, J.; Bergstad, C. Public acceptability towards environmental policy measures: Value-matching appeals. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 61, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolderdijk, J.W.; Gorsira, M.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L. Values determine the (in)effectiveness of informational interventions in promoting pro-environmental behavior. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corner, A.; Markowitz, E.; Pidgeon, N. Public engagement with climate change: The role of human values. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. It is a moral issue: The relationship between environmental self-identity, obligation-based intrinsic motivation and pro-environmental behaviour. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloot, D.; Kutlaca, M.; Medugorac, V.; Carman, P. Recycling alone or protesting together? Values as a basis for pro-environmental social change actions. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, J.; Weber, K.; Vail, R. The relationship between the perceived and actual effectiveness of persuasive messages: A meta-analysis with implications for formative campaign research. J. Commun. 2007, 57, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, J.P.; Peck, E. Affect and persuasion. Commun. Res. 2000, 27, 461–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmes, T.; Haslam, S.A.; Jans, L. A single-item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 52, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G.; Van der Werff, E.; Lurvink, J. The Significance of hedonic values for environmentally relevant attitudes, preferences and actions. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, C.; Varum, C.; Botelho, A. Promoting sustainable hotel guest behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C.; Rothengatter, T. A review of intervention studies aimed at household energy conservation. Elsevier 2005, 25, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, S.F.; Reidhav, C.; Lygnerud, K.; Werner, S. Sparse district-heating in Sweden. Appl. Energy 2008, 85, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. Social influence approaches to encourage resource conservation: A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | Financial Reason Was Emphasised | Environmental Reason Was Emphasised | Communal Reason Was Emphasised |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial appeal | 88% | 27% | 1% |

| Environmental appeal | 1% | 99% | 2% |

| Communal appeal | 7% | 46% | 76% |

| Descriptive Statistics per Appeal Condition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial | Environmental | Communal | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Perceived message quality | 3.31 a | 1.02 | 3.95 b | 1.14 | 3.72 b | 1.19 |

| Interest to join | 3.41 | 1.33 | 3.46 | 1.28 | 3.57 | 1.42 |

| Information request | 34% | 40% | 37% | |||

| Environmental Reason Was Emphasised | Communal Reason Was Emphasised | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | M | SD | M | SD |

| Environmental appeal | 6.38 | 0.81 | 4.26 | 1.63 |

| Communal appeal | 3.87 | 2.02 | 6.27 | 0.97 |

| Combined appeal | 6.14 | 1.22 | 6.25 | 1.05 |

| Descriptive Statistics per Appeal Condition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Communal | Combined env/com | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Perceived message quality | 4.47 | 1.31 | 4.75 | 1.03 | 4.64 | 1.21 |

| Interest to join | 4.52 | 1.49 | 4.15 | 1.45 | 4.37 | 1.50 |

| Choice to take a flyer | 52% | 48% | 60% | |||

| Manipulation Check Statement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Message Is Financial | Message Is Environmental | Message Is Communal | |||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Control | 4.13 | 1.63 | 4.06 | 1.81 | 4.29 | 1.55 |

| Financial appeal | 5.63 | 0.96 | 3.87 | 1.70 | 4.30 | 1.51 |

| Environmental appeal | 3.97 | 1.63 | 5.48 | 1.39 | 4.19 | 1.42 |

| Communal appeal | 3.66 | 1.40 | 3.66 | 1.70 | 6.31 | 0.93 |

| Descriptive Statistics per Experimental Condition | Inferential Statistics | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial | Environmental | Communal | Control | ANOVA | |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F(3,120) | p | partial η² | |

| Perceived message quality | 3.63 | 1.03 | 3.88 | 1.35 | 3.82 | 1.24 | 3.61 | 1.29 | 0.35 | 0.787 | 0.009 |

| Interest to join | 3.78 | 1.27 | 3.71 | 1.75 | 4.12 | 1.54 | 3.87 | 1.63 | 0.40 | 0.751 | 0.010 |

| Perceived benefits of joining | F(3,119) | ||||||||||

| Financial | 4.95 | 1.21 | 4.94 | 1.51 | 5.50 | 0.95 | 5.41 | 1.11 | 1.81 | 0.150 | 0.044 |

| Environmental | 5.25 | 1.03 | 4.69 | 1.70 | 5.57 | 1.42 | 5.31 | 1.27 | 4.28 | 0.087 | 0.053 |

| Communal | 4.67 | 0.97 | 4.84 | 1.50 | 4.43 | 1.35 | 4.97 | 0.97 | 1.65 | 0.381 | 0.025 |

| Environmental Benefits | Communal Benefits | Membership Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial benefits | 0.019 | 0.098 | 0.131 |

| Environmental benefits | 0.504 ** | −0.018 | |

| Communal benefits | 0.080 | ||

| Membership ratio |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sloot, D.; Jans, L.; Steg, L. Is an Appeal Enough? The Limited Impact of Financial, Environmental, and Communal Appeals in Promoting Involvement in Community Environmental Initiatives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031085

Sloot D, Jans L, Steg L. Is an Appeal Enough? The Limited Impact of Financial, Environmental, and Communal Appeals in Promoting Involvement in Community Environmental Initiatives. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031085

Chicago/Turabian StyleSloot, Daniel, Lise Jans, and Linda Steg. 2021. "Is an Appeal Enough? The Limited Impact of Financial, Environmental, and Communal Appeals in Promoting Involvement in Community Environmental Initiatives" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031085

APA StyleSloot, D., Jans, L., & Steg, L. (2021). Is an Appeal Enough? The Limited Impact of Financial, Environmental, and Communal Appeals in Promoting Involvement in Community Environmental Initiatives. Sustainability, 13(3), 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031085