Abstract

In an effort to suggest an extended role that art could play in promoting a pro-ecological worldview, this study reviews a two-week artist-led workshop, organized as part of an undergraduate art course offered by a university specializing in engineering and the natural sciences. To explore the potential impact of studio work on engineering student perceptions, we collected data from multiple sources, including field notes, participant observations, outcomes of the group projects, and participants’ responses to studio work during the workshop. In particular, to provide educational implications, our review focused on the findings from post-project surveys collected through online questionnaires and in-person interviews. In order to make suggestions on art courses that are specifically designed to cultivate engineering students’ perceptions of the environment, we carried out online surveys based on the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale. The results of the NEP-based surveys indicated that engineering students’ anti-anthropocentrism, rejection of human exceptionalism, and acknowledgement of the possibility of an eco-crisis were significantly correlated with a belief in public welfare. By comparison, respondents’ stronger public welfare beliefs were not associated with beliefs in limits to growth and the fragility of nature’s balance. This study responds to today’s complex socio-environmental issues by contributing to the discussion about the need to integrate interdisciplinary approaches into engineering education on environmental sustainability.

1. Introduction

The increasingly challenging environmental issues of our time demand that we make fundamental changes to our sociocultural practices. In questioning traditional technocentric approaches to contemporary environmental issues, critics have stressed the need for holistic approaches that do not dismiss the role of art in the dissemination of scientific information and incorporate diverse perspectives from multiple disciplines [1,2,3]. In particular, public outreach and education have been addressed as avenues to increase support for collective behavioral change [1,3,4]. Criticism over conventional environmental education includes “an attitude of emotional detachment from nature” and “the limited scope and perspective of environmental education in general” [5] (p. 13). For problems in the traditional and measurable result-oriented learning system of environmental education [6], educational researchers have examined how the arts can help individuals to engage with ecological issues, communicate their environmental concerns, and propose creative solutions to environmental challenges, expanding the way in which they approach scientific practices [7,8].

Among the empirical studies that have explored the potential of art in various educational settings, Savva, Trims, and Zachariou [9] demonstrated that artistic activities increased their participants’ emotional engagement and promoted environmental awareness. In a study conducted by Jacobson et al. [3], the learning outcomes of an interdisciplinary fieldtrip to a remote marine lab for graduate students from fine arts and natural resource science departments were examined. The authors discovered that the interdisciplinary setting increased student interest and motivation. Moreover, the integrated approach helped to establish emotional connections, stimulate new dialogue, and led to more creative problem-solving amongst the participants. These previous educational discussions suggest that integrated art projects carry the potential to contribute to a pro-ecological view amongst learners. Nevertheless, art projects and environmental awareness have rarely been discussed in tandem during efforts to educate engineering students whose products, knowledge, and belief systems clearly impact environmental sustainability. Although interdisciplinary programs for engineering students have often included liberal arts and ethics, discussions about hands-on experiences with works of art remain scarce [10,11]. Indeed, while several previous studies have measured engineering students’ ecocentric orientation following interdisciplinary education, none have discussed the ways in which art influences these factors [12,13].

Aiming to provide a viable solution that can connect engineering education to the multilateral aspects of ecological values, this study reviews a two-week artist-led workshop, organized as part of an undergraduate art course offered by a university specializing in engineering and the natural sciences. The study was conducted as a form of practitioner inquiry, whereby practitioners play the role of knowledge generators. One particular benefit of this approach is that it is conducted by inquiry-oriented classroom practitioners, meaning that their “theories and knowledge are generated from research grounded in the realities of educational practice” [14] (p. 4). To explore the potential impact of studio work on student perceptions, the workshop was carefully designed to create a lively art experience that would have students work with two practicing artists experienced at developing ecological art projects. During the workshop we collected data from multiple sources, including field notes, participant observations, outcomes of the group project, and participants’ responses to studio work collected using an online questionnaire and in-person interviews. The study outcomes are organized into two parts: (1) descriptions of the studio project development and its outcomes; and (2) reviews of the findings from the participants’ response to studio work.

2. Development of the Studio Project

The workshop was organized and carried out for three weeks in the fall of 2019. In conjunction with an environmental topic included in a required art course, the workshop aimed to provide a unique learning experience of exploring diverse ideas and practices in the visual arts to undergraduate engineering majors. Because most students entered the course with little art experience, the course was structured to provide them with thorough background knowledge on the subject before the beginning of the final studio project. The workshop consisted of four sequential sessions: (1) a warm-up session that provided video clips and reading materials intended to enhance students’ understanding of the art practices that take place in nature; (2) a follow-up class session that reviewed the characteristics of diverse artistic approaches to the environment and discussed the meanings and values of ecological art practices; (3) three studio work sessions where students worked in groups to develop their own projects in connection to the ecological ideas and works of two invited artists; and (4) two sessions allocated for final group presentations and the installation of project outcomes in the exhibition hall.

2.1. Visiting Artists for Studio Projects

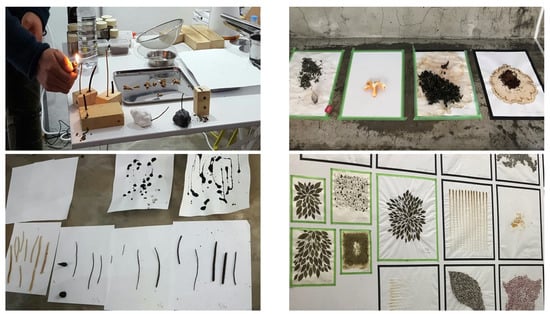

Each group’s studio projects were designed to fit with the ecological art projects that had been developed by artists Seung-Kyun Lim and Soonim Kim while they participated in the Science-Art Residency Program a year before the workshop. The residency program was organized in conjunction with Science Walden, an interdisciplinary research project aimed at building an ecologically sustainable community operated by a renewable energy resource-based economic system. During the four-week residency, the artists lived and worked in the Science Cabin, an on campus residential building that included a laboratory designed to test the effectiveness of the renewable energy system [15]. The artists living in this space were expected to broaden the vision of the Science Walden research project by stimulating innovative ideas and encouraging interdisciplinary practices. The artists’ awareness of these expectations directed them to explore methods for reflecting upon the hidden value of waste (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Visual forms explored by two artists during their residency in the Science Cabin. Lim’s Incense Works (left), Kim’s Panel Works (right). Photo provided by the ‘Science Walden’ Center.

Lim explored ways that sludge and fecal residue from the adjoining laboratory might be processed, settling on the idea of using the sludge to create incense. For this project, he spent some time reviewing a wide range of incense-making techniques developed in many different cultures. He began working by collecting sludge from both human feces and dog and bird excrement and developed it by testing the scent of those materials, mixing different materials and controlling the density. Lim’s incense work, came out as a number of paste strips set in a frame, respectively, helped him reveal ways in which the value of human waste can be reassessed. Kim developed her project using the remains of the food she consumed every day, which included seeds, fruit skins, and tea leaves. The work involved careful observation of the natural processes of change that take place in the physical properties of food remains, in addition to time-consuming labor that involved boiling, drying, separating, spreading, and stretching the remains to turn them into artistic materials. Her practice of revealing the physical properties of the energy in food waste illustrated the unrecognized value of daily waste.

2.2. Studio Activities and Group Projects

For the studio projects, ninety-two students were divided into twenty-six groups of two to four people. Four students with different majors were initially assigned to each group at the beginning of the semester. Each group was assigned to work with one of the two artists and developed its group project in relation to the ideas and works of that artist.

In the group projects that were tied to Lim’s work, students explored sense memories related to smell to generate ideas and forms and to simultaneously collect materials that could be added to their own incense projects. During the next studio activity session, Lim demonstrated the fundamental processes behind incense-making, showing students how to mix basic powders and control density using water. After learning how to make incense, each group developed their own incense project by grinding and adding various materials related to their smell memories to their mixture (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Student activities related to mixing and shaping pastes for incense-making.

For the group projects derived from Kim’s work, students began by considering what they ate and drank every day, developed ideas and forms based on these considerations, and gathered materials to be added to their own works. Individual students were asked to test the qualitative effects (such as exploring the possible range of colors and textures) of the food remains that they wanted to use before they applied those remains to their prepared panel. During the next session, students began their group work by drawing a part of their body on the panel and placing food remains that they had brought with them onto the drawing (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Students working on panels.

2.3. Project Outcomes

The project outcomes were displayed in an exhibition space for one week. Table 3 and Table 4 list the key aspects of four exemplary group projects.

Table 3.

Group projects developed from memories of smell.

Table 4.

Group projects developed with food remains.

3. Participants’ Responses to Studio Work

Participants of this workshop were 92 undergraduate students from diverse majors in engineering and natural sciences. Before the data collection, all students as well as the artists were informed about the aim of the research, data collection methods, and the right to withdraw from the study. Our collection of the data was limited to what we could collect during the workshop, which was primarily designed to encourage students to develop a stronger sense of environmental consciousness. Since we were interested in learning about the potential impact of studio work on engineering student perceptions, we consider this workshop as an intrinsic case pre-selected for the purpose of our study. To obtain credible information on the studio-work experience, we collected the students’ responses immediately after the completion of studio sessions using an anonymous online questionnaire, and the artists’ responses using 20-min in-person interviews (see Table 5). To triangulate the survey and interview data, we collected data from multiple sources, including field notes, participant observations, outcomes of the group projects [16]. By the nature of our study that looked for themes emerging from the data, we applied thematic analysis to the responses to the open-ended survey questions [17]. An initial review of the responses, focused on the notable aspects of each category, was followed by cross-data analysis that looked at the relationships between the responses. Then, we tried to draw out meanings and implications by asking contextual questions such as “In what circumstances was the student’s idea and action allowed or limited?” and “To what extent did the artist influence the student’s idea or practice?”

Table 5.

Post-studio questionnaire.

3.1. Students’ Responses

The student responses to the post-studio questionnaire indicated several consistent points.

3.1.1. Newly Recognized Role of Art

Of the 92 students who participated in the workshop, 65 (70.6%) said that the class sessions for the art and the environment topic helped them to understand art and the roles that it can play in a new light. Of these 65 positive respondents, 30.7% asserted that art was an effective medium for developing public communication. Many of them stressed that the most impactful thing that art can do is create empathy, making art a relatable and effective tool for delivering socio-political messages, bringing public attention to social issues, and raising awareness about environmental problems. Another 30.7% of the positive respondents indicated that the art and the environment topic broadened their views of what can be considered a work of art and what can be used to create art and better understood the appropriate locations for creating or displaying artworks. Their comments included: “I learned what could be considered art shouldn’t be limited to those displayed in a gallery”; “Art helps people see things that they weren’t interested in” and “Art is not only about showing one’s aesthetic sense but also sharing ideas with others and influencing changes in others’ perceptions.”

3.1.2. The Most Meaningful Part of Studio Work

Around half of the respondents reported that working with food remains and incense-making materials was the most interesting part of their experience. The most commonly cited reason for these claims was that the studio activity was unique and encouraged them to discover unusual methods in using familiar materials. More than one third of the respondents said that the process of developing ideas in collaboration with others was the most meaningful part of their work, primarily because this process demonstrated to them that people can have many feelings and interpretations about the same thing. In particular, the students involved in the incense project appreciated that their experience involved the creation of tangible objects that gave shape to their ideas about smell. Student comments in this category included: “It was quite interesting to create art based on old memories of smell”; “…in particular, to see the diverse viewpoints of others in creating stories of everyday experiences”; and “it was both challenging and interesting to shape the ideas and meanings of our group work together by coordinating different opinions”.

3.1.3. Potential Impact of Studio Work

Significant numbers of students reported that they learned the value and importance of collaboration. In particular, many appreciated the group discussions, where diverse viewpoints enriched the process of ideation and shaped project outcomes. One student surmised that “as a group, it was much more challenging. The fact that I was with others enabled me to try out things in a way that I hadn’t done before.” 15 respondents acknowledged that the studio work helped them to learn a wider range of artistic expression modes. A similar number of students also placed considerable value on the experience of translating abstract ideas, such as smell memories, into concrete visual forms. Another similar proportion of students indicated that they now saw art as a means of extending personal expression and that they had begun to perceive everyday life as a form of art and art as something to be created rather than something that already exists within a fixed system. A substantial number of students mentioned that sharing experiences and exchanging ideas with others in group discussions helped them to expand their viewpoints and that this experience would influence their thoughts and actions in future settings.

3.2. Artists’ Responses

Feedback on this kind of studio work was obtained through in-person interviews with the participating artists.

3.2.1. Expectations of Student Work

While Lim was interested in looking at the process of how students shaped ideas into concrete forms and expected them to create something of their own, Kim was more concerned with having the time for hands-on experiences that were based on quality observations of the materials. Kim pointed out the gap between her expectations and the reality of the project: “I came here with an expectation of securing enough time for students to reflect on the range of things they eat every day.” Then, she remarked that “it was quite disappointing to see that the tense academic environment at the end of the semester was too tight for the students to explore things slowly”.

3.2.2. Things Learned from Student Work

In noticing that students had a tendency to reflect on larger issues rather than personal stories, Kim remarked, “The ideas, such as the groups taking a topic of racial reconciliation or a story of family relation, seemed to be somewhat altruistic and typical. If young students in their early 20s reflected what they ate and felt, that would sound more original as a real reflection of our time.” On the other hand, Lim noted the potential benefits of the group project: “There were several groups of students who managed their problem-solving processes quite well. In particular, those who frequently formed different opinions from the other group members learned a lot from the process of coordinating opinions”.

3.2.3. Potential in Student Work

Kim valued the workshop as a setting for the discovery of new possibilities for expressing the material’s various qualities, stating that “in the group activities, I observed that some interesting colors and textures grew out from several panels. It was the unusual handling of the materials—as they were handled differently from the way I would have approached them—that made the accidental visual effects possible.” Lim also observed that he was particularly impressed by the diverse range of outcomes that resulted from students’ memories of smell and appreciated how this exercise enriched his earlier conceptualization of the incense project.

3.3. Implications

The students’ overall responses indicated that they found their hands-on activities unique and enjoyable. In particular, most students appreciated the process of creating art by using familiar materials in creative ways. The qualitatively enriched process of exploring diverse materials and visualizing ideas, which initially concerned the artists the most, was later confirmed by the students to be the most challenging and interesting part of the project. The artists also admitted that the unconventional problem-solving processes and the unusual handling of the materials that they observed during group work expanded their views. Both the students’ and the artists’ responses suggest that the workshop became a space to learn from the integration of diverse perspectives and visual experiences, which could foster creativity. In this interdisciplinary learning context, a considerable number of students predominantly valued collaboration and the contributions of their fellow group members with different majors. Interestingly, in their responses the students spoke little about the role that the artists played in the process of work development. Part of the reason seems to be the absence of questions about the artists in the questionnaire given to students (Table 5). At the same time, the shortage of class time identified in the post-studio report, which may have influenced the scope and depth of the artist–student interactions, suggests the need for less-constrained learning environments that enable artists to serve as significant sources of inspiration.

The two former resident artists were invited with the expectation that their ecological ways of thinking and creating art would play a positive role in readjusting students’ views on the human-environment relationships by stimulating the students’ environmental awareness, sensitivity, and appreciation [1,7,18]. In fact, a significant portion of the students’ responses implied that the artistic exploration by the two artists of the potential value of daily waste encouraged them to reconsider the widespread unsustainable socioeconomic practices [19]. The overall participant responses to the workshop, which show the role of art as a stimulator to develop a stronger sense of social and environmental consciousness, indicate a need for more extended interdisciplinary learning opportunities.

4. Effects of Studio Experience on Students’ Pro-Ecological Views

4.1. Data Collection and Analysis

In order to make suggestions on how an art course might be designed to cultivate pro-ecological views among engineering students in specific, we posted fifteen survey questions online. These questions were developed using the New Ecological Paradigm-Revised (NEP-R) scale and were administered after the studio sessions [20]. The NEP was originally developed by Dunlap and Van Liere [21] after they theorized that individual attitudes toward environmental problems reflected a set of primitive beliefs about the relationship between humans and the earth. Pirages and Ehrlich [22], whose research attributed environmental problems to the Dominant Social Paradigm (DSP), inspired Dunlap and Van Liere’s ideas. The DSP is characterized by the pursuit of economic growth over equity, support of technological over political solutions, and anthropocentrism rather than biocentrism. Accordingly, the NEP, a quantitative measure of pro-environmental attitudes, was comprised of inquiries into “the existence of ecological limits to growth, the importance of maintaining the balance of nature, and rejection of the anthropocentric notion that nature exists primarily for human use” [23] (p. 6).

In addition to the NEP-R, our survey measured students’ beliefs in public welfare. Students were asked to rate statements derived from the NEP and question items derived from Cech [24] using a 5-point Likert-scale. The statements included: I find “professional/ethical responsibilities”, “understanding the consequences of technology”, and “understanding how people use machines” to be important in order to make a successful career in engineering. Moreover, the following two question items measured the respondents’ social consciousnesses: I personally believe “promoting the understanding of race, gender, and class inequality”, and “helping others in need” is important. Using Pearson’s r correlation, we assessed whether respondents’ public welfare considerations correlated with their ecologically-oriented worldview. These findings are discussed below.

4.2. Survey Results

As engineers play a vital role in implementing environmental principles through their work, it is important to incorporate environmental sustainability into engineering education [25,26]. Using our survey analysis, we investigated how engineering students’ ecological views were connected to their broader perspectives of technology and society.

Bernstein and Szuster [27] argued that the views on nature, technology, and societal responses to environmental problems constitute the three key dimensions with which contemporary environmentalists have agreed or disagreed. The environmental movement has evolved substantially since the development of the NEP scale in the 1970s, leading to wide ideological scopes within contemporary pro-environmentalism. It is necessary to investigate what views of nature, technology, and society are associated with engineering students’ environmental attitudes. By adding questions to measure the students’ beliefs in public welfare, we investigated quantitatively how certain attributes of social responsibility might foster pro-environmental views and vice versa.

We were able to draw the following interpretations from our correlational analysis summarized in Table 6:

Table 6.

Correlation between the 5 facets of the NEP and 5 measures of public welfare beliefs.

- The relationship between anti-anthropocentrism and the rated importance of professional/ethical responsibilities, understanding the consequences of technology, and social consciousness was particularly strong. If engineering students have stronger public welfare beliefs, they tend to more strongly disagree with anthropocentrism and are less likely to believe that it is humanity’s right to rule over the rest of nature.

- If engineering students have stronger public welfare beliefs, they tend to reject the human exceptionalism that regards humans having exceptional status to modify or control nature to their benefit.

- If engineering students have strong public welfare beliefs, they are more prone to acknowledging the possibility of an eco-crisis to be significant.

- Somewhat surprisingly, our respondents’ degrees of endorsement for the limits to growth and the fragility of nature’s balance had no significant association with the strength of their public welfare beliefs. This means that engineering students with relatively strong public welfare beliefs, which correlated with higher scores in the other three facets of the NEP, are not more likely to view nature as a limited and delicate resource that needs to remain pristine and undisturbed.

Although previous studies have noted that all five facets of the NEP correlate with a general ecological worldview [28,29], our findings indicate distinct divisions in the belief systems of engineering students. Even engineering students with higher public welfare beliefs were not likely to endorse certain ecological perspectives, such as limits to growth or the fragility of nature’s balance. Therefore, we suggest that engineering education on environmental sustainability may prove effective if it focuses on particular facets of the NEP, such as anti-anthropocentrism. It is also important to investigate how traditional understanding of engineering education, which tend to focus more on technical knowledge, might affect engineering students’ fragmented, rather than holistic ecological worldview [30]. Further research with representative samples needs to be conducted to examine what educational settings could encourage engineering students to endorse the perspectives of limits to growth and the fragility of nature’s balance as well.

5. Discussion

This study’s studio project encouraged students to understand art as a medium for creating empathy, delivering socio-political messages, and bringing public attention to social or environmental issues. Artwork projects can equip engineering students with more skills for collaboration and public engagement. The fact that the students in the current study valued collaboration with their peers during the process of developing their work more than their contact with the visiting artists suggests the need to pay more attention to the relationship between learners’ engineering identities and their ecological perspectives.

In the surveys we administered, a correlation between public welfare beliefs and pro-environmental measures was limited to anti-anthropocentrism, the rejection of human exceptionalism, and the possibility of an eco-crisis from the categories of the NEP-R scale. The students’ beliefs in the limits to growth and the fragility of nature’s balance did not increase with the strength of their public welfare beliefs. Unlike these divided findings, previous studies that have used the NEP scale to measure pro-environment attitudes and cultures have noted relationships among all five facets of the NEP. Our study indicates the need to develop an interdisciplinary program that is specifically designed to cultivate engineering students’ ecological attitudes.

Our findings suggest that anti-anthropocentrism, the rejection of human exceptionalism, and acknowledging the possibility of an eco-crisis could prove useful as educational foci for encouraging future engineers to develop environmental awareness. The studio art project provided a quality venue for our respondents to achieve this purpose. As students interacted with material objects, their positions as autonomous subjects were partially displaced by the non-human, non-anthropocentric agency of those objects. Their human ideas were transformed into concrete (yet simultaneously transient) shapes that represented their abstract memories before they inevitably decomposed.

6. Conclusions

In the data collected at the investigated workshop, we discovered evidence that students formed and shared an environmental and social consciousness. Many claimed that their views on art and the environment were broadened and that they began to see art as an effective medium for public communication. Although the role of the artists who supervised the studio work was somewhat less significant than we had expected, the students’ overall responses to the studio experience indicate that integrated art projects carry the potential to encourage pro-ecological views among engineering students. Both the resident artists and the engineering students stated that their environmental awareness had changed due to their mutual interaction. Such findings contribute to the currently growing discussion on the need to bring interdisciplinary approaches to engineering education about environmental sustainability and to be more responsive to the complex socio-environmental issues we face today. Further studies in different socio-cultural contexts may expand the scope of our understanding on the more extended and socially responsive role of art in this type of educational setting. As it suggests that interactions with artists could provide a meaningful basis for considering pro-environmental values, our research shows how engineering education curricula can be designed to facilitate students’ considerations of ecological issues from diverse perspectives through hands-on experience in studio art practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.-M.P.; methodology, K.-M.P. and H.K.; software, H.K.; validation, H.K.; formal analysis, H.K.; investigation, K.-M.P.; resources, K.-M.P.; data curation, K.-M.P. and H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.-M.P. and H.K.; writing—review and editing, K.-M.P. and H.K.; studio project administration, K.-M.P.; funding acquisition, K.-M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2015R1A5A7037825).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the reason that students’ participation was voluntary and individual students cannot be identified.

Informed Consent Statement

Student consent was waived due to the reason that students’ participation was voluntary and individual students cannot be identified.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Curtis, D.J.; Reid, N.; Ballard, G. Communicating ecology through art: What scientists think. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadzigeorgiou, Y.; Skoumios, M. The development of environmental awareness through school science: Problems and possibilities. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2013, 8, 405–426. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, S.K.; Seavey, J.R.; Mueller, R.C. Integrated science and art education for creative climate change communication. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurevitz, R. Affective approaches to environmental education: Going beyond the imagined worlds of childhood? Ethics Place Environ. 2000, 3, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.I.K. Exploring connections between environmental education and ecological public art. Child. Educ. 2008, 85, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.J. Challenges for environmental education: Issues and ideas for the 21st century. BioScience 2001, 51, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertling, J.G. The art of empathy: A mixed methods case study of a critical place-based Art Education Program. Int. J. Educ. Arts 2015, 16. Available online: http://www.ijea.org/v16n13/ (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Inwood, H.J. At the crossroads: Situating place-based art education. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 13, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Savva, A.; Trimis, E.; Zachariou, A. Exploring the links between visual arts and environmental education: Experiences of teachers participating in an in-service training programme. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2004, 23, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, R.; Gibbs, B. Connecting engineering processes and responsible innovation: A response to macro-ethical challenges. Eng. Stud. 2019, 11, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillette, D.D.; Lowham, E.; Haungs, M. When the hurly-burly’s done, of battles lost and won: How a hybrid program of study emerged from the toil and trouble of stirring liberal arts into an engineering cauldron at a public polytechnic. Eng. Stud. 2014, 6, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, D.; Assaraf, O.B.; Shemesh, J. “Human Nature”: Chemical-engineering students’ ideas about human relationships with the natural world. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2014, 39, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S.-Y.; Jackson, N.L. Influence of an Environmental Studies Course on Attitudes of Undergraduates at an Engineering University. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, N.F.; Yendol-Silva, D. The Reflective Educator’s Guide to Classroom Research: Learning to Reach and Teaching to Learn through Practitioner Inquiry; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paek, K. The Transformative Potential of Creative Art Practices in the Context of Interdisciplinary Research. Creat. Stud. 2019, 12, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stake, R. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hollis, C.L. On developing an art and ecology curriculum. Art Educ. 1997, 50, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R. Critical Pedagogy, Ecoliteracy, and Planetary Crisis: The Ecopedagogy Movement; Peter Lang Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “new environmental paradigm”: A proposed measuring instrument and preliminary results. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirages, D.C.; Ehrlich, P.R. Ark II: Social Responses to Environmental Imperatives; W. H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E. The new environmental paradigm scale: From marginality to worldwide use. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 40, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, E.A. Culture of disengagement in engineering education? Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2014, 39, 42–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academy of Engineering. Emerging Technologies and Ethical Issues in Engineering; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology. Criteria for Accrediting Engineering Programs: Effective for Evaluations during the 2010–2011 Accreditation Cycle. Available online: https://www.abet.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/criteria-eac-2010-2011.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Bernstein, J.; Szuster, B.W. The new environmental paradigm scale: Reassessing the operationalization of contemporary environmentalism. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 50, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A. The NEP scale: Measuring ecological attitudes/worldviews in an African context. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 1477–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amburgey, J.W.; Thoman, D.B. Dimensionality of the new ecological paradigm: Issues of factor structure and measurement. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.; Luk, L.Y. Academics’ beliefs towards holistic competency development and assessment: A case study in engineering education. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2022, 72, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).