Top Management Team Stability and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Effects of Performance Aspiration Gap and Organisational Slack

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Literature Review

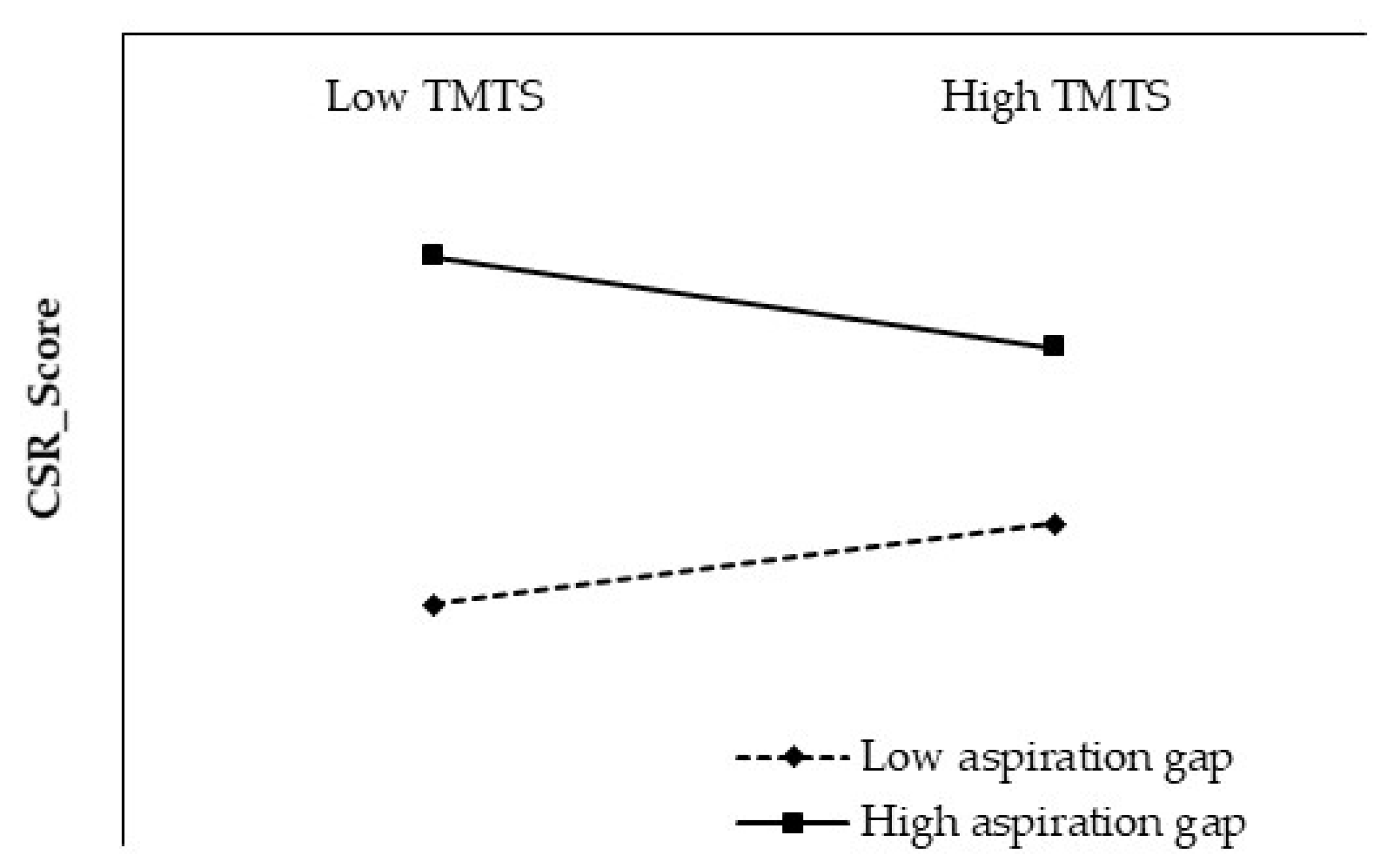

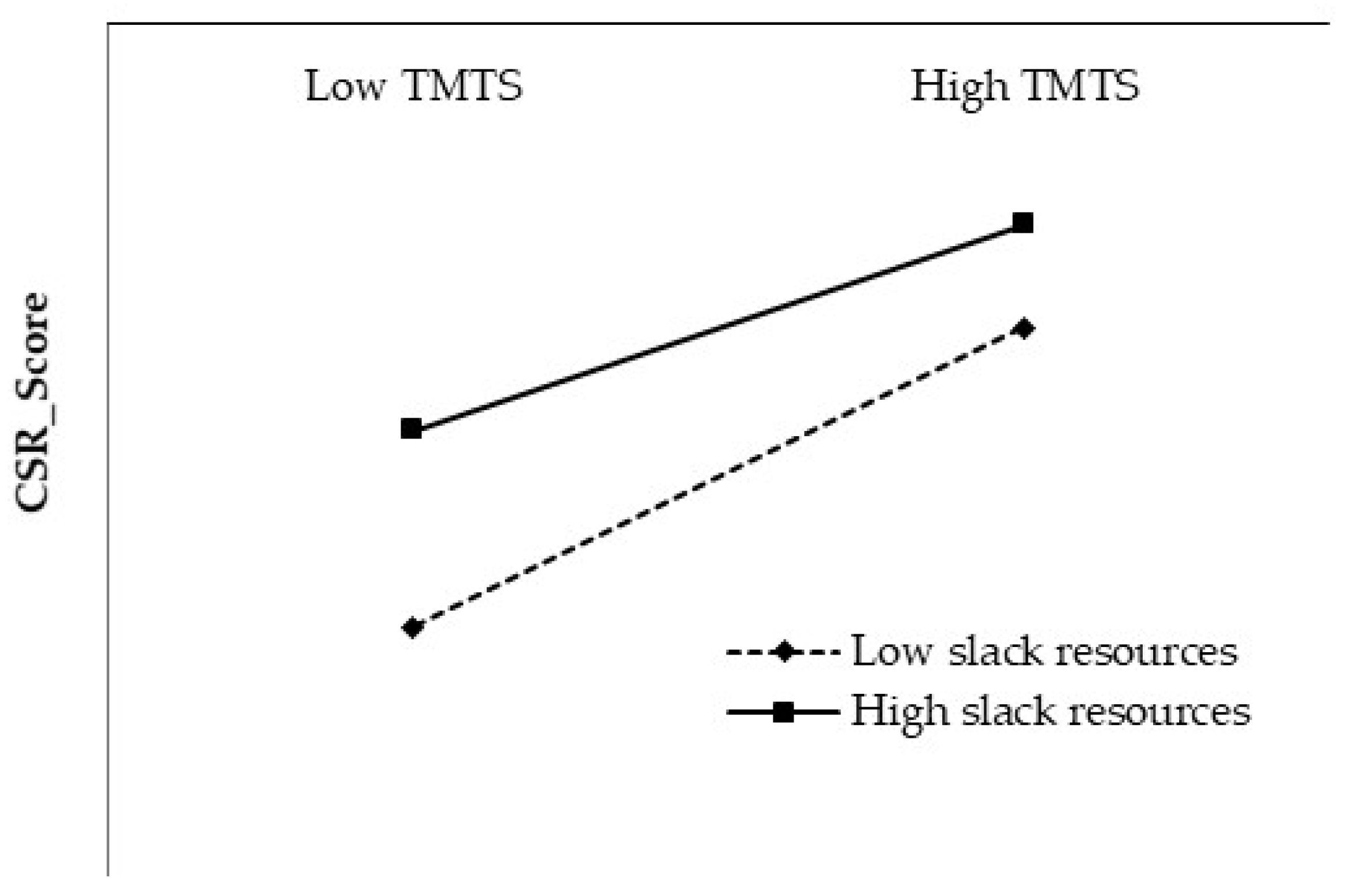

2.2. Hypotheses Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Variable Description

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variable

3.2.3. Control Variables

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Regression Results

4.2. Robustness Tests

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brickson, S.L. Organizational identity orientation: The genesis of the role of the firm and distinct forms of social value. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 864–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, N.; Calvo, F. Corporate social responsibility and multiple agency theory: A case study of internal stakeholder engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.B.; Montanari, J.B. Strategic management of the socially responsible firm: Integrating management and marketing theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U. Absorptive capacity, environmental turbulence, and the complementarity of organizational learning processes. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 822–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.N.; Klebanov, M.M.; Sorensen, M. Which CEO characteristics and abilities matter? J. Financ. 2012, 67, 973–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eberle, D.; Berens, G.; Li, T. The impact of interactive corporate social responsibility communication on corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X. Impression management against early dismissal? CEO succession and corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 999–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Qian, C.; Chen, G.; Shen, R. How CEO hubris affects corporate social (ir) responsibility. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1338–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Kuzey, C.; Kilic, M.; Karaman, A.S. Board structure, financial performance, corporate social responsibility performance, CSR committee, and CEO duality: Disentangling the connection in healthcare. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, S.; Rahman, N.; Post, C. The impact of board diversity and gender composition on corporate social responsibility and firm reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Zhu, H.; Ding, H.-B. Board composition and corporate social responsibility: An empirical investigation in the post Sarbanes-Oxley era. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Tilt, C. Board composition and corporate social responsibility: The role of diversity, gender, strategy and decision making. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, C.; Velayutham, E. The influence of board committee structures on voluntary disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions: Australian evidence. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2018, 50, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, R.S.; Fryxell, G.E. Are conglomerates less environmentally responsible? An empirical examination of diversification strategy and subsidiary pollution in the US chemical industry. J. Bus. Ethics 1999, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Salomon, R.M. Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1304–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.S.; Simerly, R.L. The chief executive officer and corporate social performance: An interdisciplinary examination. J. Bus. Ethics 1994, 13, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.; Logsdon, J.M. How corporate social responsibility pays off. Long Range Plan. 1996, 29, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Holmström, B. Managerial incentive problems: A dynamic perspective. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1999, 66, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.J.; Zimmerman, J.L. Financial performance surrounding CEO turnover. J. Account. Econ. 1993, 16, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishina, Y.; Dykes, B.J.; Block, E.S.; Pollock, T.G. Why “good” firms do bad things: The effects of high aspirations, high expectations, and prominence on the incidence of corporate illegality. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 701–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Zhang, C. Corporate social responsibility and firm risk: Theory and empirical evidence. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 4451–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minor, D.; Morgan, J. CSR as reputation insurance: Primum non nocere. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 53, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, K. Does religion benefit corporate social responsibility (CSR)? Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1206–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Chen, S.; Chen, P. The Relationship between Female Top Managers and Corporate Social Responsibility in China: The Moderating Role of the Marketization Level. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. Confucianism, socialism, and capitalism: A comparison of cultural ideologies and implied managerial philosophies and practices in the PR China. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenkar, O.; Ronen, S. Structure and importance of work goals among managers in the People’s Republic of China. Acad. Manag. J. 1987, 30, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manner, M.H. The impact of CEO characteristics on corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.K.; Hambrick, D.C.; Treviño, L.K. Political ideologies of CEOs: The influence of executives’ values on corporate social responsibility. Adm. Sci. Q. 2013, 58, 197–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.H.; Dey, A.; Smith, A.J. CEO materialism and corporate social responsibility. Account. Rev. 2019, 94, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, S.; Oliver, B.; Song, S. Corporate social responsibility and CEO confidence. J. Bank Financ. 2017, 75, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fabrizi, M.; Mallin, C.; Michelon, G. The role of CEO’s personal incentives in driving corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daboub, A.J.; Rasheed, A.M.; Priem, R.L.; Gray, D. Top management team characteristics and corporate illegal activity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 138–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X. Potentials of top management team career development and corporate social responsibility: A study on listed manufacturing companies in China. Career Dev. Int. 2019, 24, 560–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Nakagawa, K.; Li, J. Impacts of top management team characteristics on corporate charitable activity: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. J. Int. Bus. Econ. 2019, 7, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shahab, Y.; Ntim, C.G.; Chengang, Y.; Ullah, F.; Fosu, S. Environmental policy, environmental performance, and financial distress in China: Do top management team characteristics matter? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 1635–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.S.; Pearson, J.N. Strategically managed buyer–supplier relationships and performance outcomes. J. Oper. Manag. 1999, 17, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z. Is environmental innovation conducive to corporate financing? The moderating role of advertising expenditures. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Shah, S.Z.; Akbar, S. Value relevance of advertising expenditure: A review of the literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, L.A.; Kiefer, C.F. Just Start: Take Action, Embrace Uncertainty, Create the Future; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. The value of corporate culture. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 117, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, A.S.; Calantone, R.J.; Griffith, D.A. Strategic change and termination of interfirm partnerships. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 402–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bruton, G.D.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Transgenerational Succession and R&D Investment: A Myopic Loss Aversion Perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 46, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Germann, F.; Grewal, R. Washing away your sins? Corporate social responsibility, corporate social irresponsibility, and firm performance. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Corporate reputation and philanthropy: An empirical analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Husted, B.W.; Allen, D.B. Corporate Social Strategy: Stakeholder Engagement and Competitive Advantage; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Korsgaard, M.A.; Schweiger, D.M.; Sapienza, H.J. Building commitment, attachment, and trust in strategic decision-making teams: The role of procedural justice. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amason, A.C. Distinguishing the effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict on strategic decision making: Resolving a paradox for top management teams. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uskul, A.K.; Oyserman, D.; Schwarz, N. Cultural Emphasis on Honor, Modesty, or Self-Enhancement: Implications for the Survey Response Process; Kent Academic Repository: Kent, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Fraser, C.; Jaspars, J.M.F. The Social Dimension: Volume 1: European Developments in Social Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pontrandolfo, P.; Pujari, D. Developing sustainable new products in the textile and upholstered furniture industries: Role of external integrative capabilities. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitenga, A.L.; Tearney, M.G. Mandatory CEO retirements, discretionary accruals, and corporate governance mechanisms. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2003, 18, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W.-Y.; Chang, Y.K.; Cheng, Z. When CEO career horizon problems matter for corporate social responsibility: The moderating roles of industry-level discretion and blockholder ownership. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.V.; Garcia, A.; Rodriguez, L. Sustainable development and corporate performance: A study based on the Dow Jones sustainability index. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, J.D.; Fredrickson, J.W. Who directs strategic change? Director experience, the selection of new CEOs, and change in corporate strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 1113–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D.; Donaldson, L. Toward a stewardship theory of management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, D.C.; Lam, S.S. The effects of job complexity and autonomy on cohesiveness in collectivistic and individualistic work groups: A cross-cultural analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 979–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm; Englewood Cliffs: Bergen, NJ, USA, 1963; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-Y.; Miner, A.S. Organizational learning from extreme performance experience: The impact of success and recovery experience. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, C. The antecedents of deinstitutionalization. Organ. Stud. 1992, 13, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, A.T.; Schmidt, R.M. Executive compensation, management turnover, and firm performance: An empirical investigation. J. Account. Econ. 1985, 7, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.W.; Shepherd, D.A.; Wiklund, J. The importance of slack for new organizations facing ‘tough’environments. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1071–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassen, R.; Hinze, A.-K.; Hardeck, I. Impact of ESG factors on firm risk in Europe. J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 86, 867–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, L.J., III. On the measurement of organizational slack. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1981, 6, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibenstein, H. Organizational or frictional equilibria, X-efficiency, and the rate of innovation. Q. J. Econ. 1969, 83, 600–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M. Exploring the origins of organizational paths: Empirical evidence from newly founded firms. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1143–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.; Zhao, H.X. Behind organizational slack and firm performance in China: The moderating roles of ownership and competitive intensity. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2009, 26, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masulis, R.W.; Wang, C.; Xie, F. Corporate governance and acquirer returns. J. Financ. 2007, 62, 1851–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.L.; Kesner, I.F. Organizational slack and response to environmental shifts: The impact of resource allocation patterns. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.M.; Yang, H.; Quan, J.M.; Lu, Y. Organizational slack and corporate social performance: Empirical evidence from China’s public firms. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Xu, R.; Liao, X.; Zhang, S. Do CSR ratings converge in China? A comparison between RKS and Hexun scores. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crutchley, C.E.; Garner, J.L.; Marshall, B.B. An examination of board stability and the long-term performance of initial public offerings. Finan. Manag. 2002, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ref, O.; Shapira, Z. Entering new markets: The effect of performance feedback near aspiration and well below and above it. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1416–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromiley, P.; Harris, J.D. A comparison of alternative measures of organizational aspirations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, E.; Huang, Y.; Peng, M.W.; Zhuang, G. Resources, aspirations, and emerging multinationals. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2016, 23, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-R. Determinants of firms’ backward-and forward-looking R&D search behavior. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Ntim, C.G.; Ullah, F. The brighter side of being socially responsible: CSR ratings and financial distress among Chinese state and non-state owned firms. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2019, 26, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.W. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory. Account. Organ. Soc. 1992, 17, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, H.; Kacperczyk, M. The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Jo, H.; Pan, C. Doing well while doing bad? CSR in controversial industry sectors. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, R. Corporate social responsibility, ownership structure, and political interference: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.M.; Gang, B.; Fareed, Z.; Khan, A. How does CEO tenure affect corporate social and environmental disclosures in China? Moderating role of information intermediaries and independent board. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 9204–9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.; Lin, T.P.; Zhang, Y. Corporate board and corporate social responsibility assurance: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W.-Y.; Chang, Y.K.; Kim, T.-Y. Complementary or substitutive effects? Corporate governance mechanisms and corporate social responsibility. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2716–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J.C.; Kraay, A.C. Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Rev. Econ. Statist. 1998, 80, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; He, L.; Zhong, L. Business groups and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2018, 37, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Salomon, R.M. Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 1101–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Long, X.; Schuler, D.A.; Luo, H.; Zhao, X. External corporate social responsibility and labor productivity: A S-curve relationship and the moderating role of internal CSR and government subsidy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gulzar, M.A.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q. Do interaction and education moderate top management team age heterogeneity and corporate social responsibility? Soc. Behav. Pers. 2018, 46, 2063–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; Gupta, V. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Sage publications: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| Industry/Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture/Forestry/Farming/Fishery | 24 | 34 | 29 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 37 | 36 | 35 | 36 | 330 |

| Mining/Metallurgy | 40 | 49 | 52 | 53 | 57 | 63 | 64 | 66 | 69 | 71 | 584 |

| Food/Textiles | 105 | 132 | 145 | 151 | 152 | 159 | 166 | 178 | 198 | 199 | 1585 |

| Furniture/Chemicals/Pharmaceuticals | 283 | 340 | 391 | 406 | 407 | 420 | 443 | 504 | 582 | 605 | 4381 |

| Machinery/Equipment | 470 | 622 | 749 | 805 | 827 | 869 | 941 | 1029 | 1193 | 1225 | 8730 |

| Other Manufacturing | 24 | 31 | 27 | 34 | 36 | 41 | 47 | 55 | 61 | 62 | 418 |

| Utilities/Energy | 52 | 53 | 57 | 56 | 60 | 68 | 76 | 79 | 81 | 84 | 666 |

| Architectural/Construction | 29 | 36 | 50 | 54 | 56 | 60 | 65 | 77 | 79 | 79 | 585 |

| Wholesale/Retail | 88 | 102 | 126 | 129 | 124 | 126 | 129 | 138 | 143 | 148 | 1253 |

| Transportation/Logistic/Distribution | 38 | 41 | 45 | 54 | 55 | 57 | 62 | 66 | 74 | 78 | 570 |

| Hospitality/Restaurant/Food Services | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 90 |

| Telecom Operators/Service Providers | 66 | 95 | 100 | 118 | 128 | 134 | 163 | 201 | 233 | 246 | 1484 |

| Real Estate Development | 106 | 112 | 125 | 118 | 116 | 115 | 113 | 109 | 111 | 109 | 1134 |

| Property Management | 16 | 24 | 19 | 19 | 21 | 20 | 35 | 38 | 46 | 48 | 286 |

| Science Research/Technology Services | 6 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 17 | 21 | 26 | 44 | 49 | 205 |

| Public Facilities Management | 4 | 5 | 22 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 31 | 34 | 43 | 45 | 262 |

| Entertainment/Leisure/Sports and Fitness | 8 | 14 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 32 | 36 | 43 | 53 | 54 | 305 |

| Conglomerates | 39 | 42 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 16 | 14 | 216 |

| Total | 1407 | 1750 | 1994 | 2114 | 2159 | 2271 | 2456 | 2704 | 3069 | 3160 | 23,084 |

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | p50 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR score | 23,084 | 24.72 | 16.03 | −3.28 | 21.99 | 74.88 |

| TMTS | 23,084 | 0.89 | 0.076 | 0.636 | 0.899 | 1 |

| Aspiration gap | 23,084 | 0.092 | 0.354 | −0.735 | 0.026 | 1.902 |

| Slack resources | 23,084 | 1.696 | 1.852 | 0.246 | 1.062 | 11.59 |

| SOE | 23,084 | 0.385 | 0.487 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Firm age | 23,084 | 2.826 | 0.351 | 1.609 | 2.89 | 3.466 |

| Firm size | 23,084 | 22.16 | 1.291 | 19.8 | 21.98 | 26.15 |

| Asset debt ratio | 23,084 | 0.664 | 0.454 | 0.077 | 0.558 | 2.657 |

| Growth | 23,084 | 0.448 | 1.268 | −0.669 | 0.144 | 9.631 |

| Top1 rate | 23,084 | 34.9 | 14.88 | 8.8 | 32.97 | 74.82 |

| Independent ratio | 23,084 | 0.375 | 0.054 | 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.571 |

| Board size | 23,084 | 2.249 | 0.177 | 1.792 | 2.303 | 2.773 |

| Dual | 23,084 | 0.26 | 0.439 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| TMT average age | 23,084 | 49.06 | 3.127 | 41.39 | 49.14 | 56.38 |

| TMT male ratio | 23,084 | 0.819 | 0.108 | 0.526 | 0.833 | 1 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 1. CSR score | / | |||||||

| 2. TMTS | 0.084 *** | 1.05 | ||||||

| 3. Aspiration gap | 0.160 *** | 0.058 *** | 1.04 | |||||

| 4. Slack resources | 0.016 ** | 0.079 *** | 0.135 *** | 1.26 | ||||

| 5. SOE | 0.132 *** | −0.078 *** | −0.022 *** | −0.231 *** | 1.42 | |||

| 6. Firm age | −0.063 *** | −0.081 *** | −0.115 *** | −0.166 *** | 0.182 *** | 1.16 | ||

| 7. Firm size | 0.282 *** | −0.065 *** | −0.092 *** | −0.378 *** | 0.344 *** | 0.165 *** | 1.48 | |

| 8. Asset debt ratio | 0.083 *** | 0.016 ** | 0.005 | −0.192 *** | 0.079 *** | −0.013 ** | 0.061 *** | 1.08 |

| 9. Growth | 0.029 *** | −0.046 *** | −0.011 * | −0.032 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.058 *** | 0.025 *** | −0.143 *** |

| 10. Top1 rate | 0.147 *** | 0.004 | 0.018 *** | −0.051 *** | 0.225 *** | −0.105 *** | 0.212 *** | 0.087 *** |

| 11.Independent ratio | −0.011 * | −0.034 *** | −0.034 *** | 0.011 * | −0.052 *** | −0.022 *** | 0.024 *** | −0.035 *** |

| 12. Board size | 0.140 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.028 *** | −0.124 *** | 0.261 *** | 0.026 *** | 0.258 *** | 0.044 *** |

| 13. Dual | −0.065 *** | 0.036 *** | 0.002 | 0.132 *** | −0.297 *** | −0.094 *** | −0.181 *** | −0.046 *** |

| 14. TMT average age | 0.088 *** | 0.112 *** | −0.058 *** | −0.148 *** | 0.344 *** | 0.209 *** | 0.356 *** | 0.034 *** |

| 15. TMT male ratio | 0.075 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.011 * | −0.126 *** | 0.236 *** | −0.045 *** | 0.188 *** | 0.047 *** |

| Variables | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| 9. Growth | 1.03 | |||||||

| 10. Top1 rate | 0.015 ** | 1.13 | ||||||

| 11.Independent ratio | 0.019 *** | 0.048 *** | 1.45 | |||||

| 12. Board size | −0.023 *** | 0.026 *** | −0.523 *** | 1.63 | ||||

| 13. Dual | −0.024 *** | −0.048 *** | 0.113 *** | −0.183 *** | 1.13 | |||

| 14. TMT average age | −0.025 *** | 0.130 *** | −0.028 *** | 0.217 *** | −0.177 *** | 1.35 | ||

| 15. TMT male ratio | −0.029 *** | 0.068 *** | −0.065 *** | 0.177 *** | −0.128 *** | 0.249 *** | 1.14 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMTS | 5.409 *** | 7.097 *** | 9.810 *** | 10.858 *** | |

| (0.787) | (0.823) | (1.454) | (1.641) | ||

| Aspiration gap | 15.625 ** | 14.484 ** | |||

| (4.847) | (4.844) | ||||

| TMTS × Aspiration gap | −13.938 *** | −12.846 *** | |||

| (3.533) | (3.544) | ||||

| Slack resources | 3.293 *** | 2.923 *** | |||

| (0.498) | (0.669) | ||||

| TMTS × Slack sources | −2.914 *** | −2.576 *** | |||

| (0.577) | (0.721) | ||||

| SOE | −1.218 ** | −1.219 ** | −1.143 ** | −1.100 ** | −1.039 ** |

| (0.476) | (0.461) | (0.429) | (0.475) | (0.448) | |

| Firm age | −3.759 ** | −3.582 ** | −3.281 ** | −1.679 | −1.575 |

| (1.304) | (1.339) | (1.208) | (1.304) | (1.252) | |

| Firm size | 4.417 *** | 4.437 *** | 4.441 *** | 4.771 *** | 4.741 *** |

| (0.509) | (0.513) | (0.494) | (0.489) | (0.492) | |

| Asset debt ratio | 6.019 *** | 6.019 *** | 5.876 *** | 6.601 *** | 6.409 *** |

| (0.472) | (0.480) | (0.396) | (0.466) | (0.391) | |

| Growth | 0.260 *** | 0.266 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.280 *** | 0.250 *** |

| (0.077) | (0.076) | (0.062) | (0.076) | (0.062) | |

| Top1 rate | 0.043 *** | 0.043 *** | 0.041 *** | 0.043 *** | 0.041 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.007) | |

| Independent ratio | 7.473 * | 7.532 * | 8.115 ** | 7.718 * | 8.249 ** |

| (3.616) | (3.573) | (3.308) | (3.567) | (3.318) | |

| Board size | 1.621 | 1.563 | 1.701 | 1.424 | 1.568 |

| (1.100) | (1.072) | (1.078) | (1.068) | (1.071) | |

| Dual | −0.521 | −0.531 * | −0.541 * | −0.591 * | −0.595 * |

| (0.291) | (0.286) | (0.281) | (0.292) | (0.287) | |

| TMT average age | −0.102 | −0.160 ** | −0.153 ** | −0.144 ** | −0.140 * |

| (0.058) | (0.061) | (0.062) | (0.062) | (0.063) | |

| TMT male ratio | 1.794 | 1.740 | 1.486 | 1.803 | 1.557 |

| (1.691) | (1.685) | (1.711) | (1.626) | (1.659) | |

| Constant | −67.881 *** | −70.594 *** | −74.169 *** | −89.068 *** | −90.536 *** |

| (13.664) | (13.568) | (11.667) | (12.950) | (12.207) | |

| Year/Industry | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Within R2 | 0.176 | 0.176 | 0.184 | 0.181 | 0.187 |

| F | 131.9 *** | 989.4 *** | 99.66 *** | 49.31 *** | 83.91 *** |

| Variables | Heckman Second Phase | PSM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| TMTS | 5.385 *** | 6.886 *** | 9.485 *** | 10.389 *** | 6.098 *** | 7.740 *** | 9.557 *** | 10.618 *** |

| (0.806) | (0.815) | (1.465) | (1.619) | (1.379) | (1.585) | (2.026) | (2.170) | |

| Aspiration gap | 14.153 ** | 13.101 ** | 15.290 ** | 14.342 ** | ||||

| (4.872) | (4.884) | (6.369) | (6.311) | |||||

| TMTS × Aspiration gap | −12.032 *** | −11.043 ** | −13.524 ** | −12.620 ** | ||||

| (3.537) | (3.574) | (5.475) | (5.437) | |||||

| Slack resources | 3.136 *** | 2.780 *** | 2.591 *** | 2.257 *** | ||||

| (0.472) | (0.655) | (0.530) | (0.679) | |||||

| TMTS × Slack sources | −2.726 *** | −2.408 *** | −2.200 *** | −1.901 ** | ||||

| (0.538) | (0.698) | (0.628) | (0.758) | |||||

| IMR | −54.633 *** | −61.936 *** | −54.718 *** | −61.750 *** | ||||

| (7.165) | (5.885) | (7.104) | (5.933) | |||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | 35.697 ** | 46.293 ** | 17.403 | 29.636 | −71.464 *** | −76.489 *** | −88.822 *** | −91.642 *** |

| (13.761) | (17.302) | (13.164) | (17.244) | (20.331) | (18.386) | (18.833) | (17.884) | |

| Year/Industry | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 23,084 | 23,084 | 23,084 | 23,084 | 12,490 | 12,490 | 12,490 | 12,490 |

| Within R2 | 0.1789 | 0.1868 | 0.183 | 0.1901 | 0.1783 | 0.1855 | 0.1815 | 0.188 |

| F | 795.7 *** | 113.3 *** | 342.7 *** | 136.6 *** | 55.31 *** | 158.6 *** | 59.72 *** | 148.0 *** |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shareholder | Society | Environment | Employee | Customer | |

| TMTS | 4.178 *** | 1.101 ** | 2.378 *** | 1.186 *** | 2.135 *** |

| (0.408) | (0.354) | (0.597) | (0.273) | (0.324) | |

| Aspiration gap | 11.455 ** | 3.823 ** | −0.574 | −0.109 | −0.274 |

| (3.641) | (1.350) | (0.571) | (0.397) | (0.497) | |

| TMTS × Aspiration gap | −9.620 *** | −3.317 ** | 0.322 | −0.095 | 0.050 |

| (2.665) | (1.056) | (0.622) | (0.394) | (0.525) | |

| Slack resources | 1.042 *** | 0.096 | 0.812 *** | 0.384 *** | 0.623 *** |

| (0.155) | (0.126) | (0.198) | (0.101) | (0.153) | |

| TMTS × Slack sources | −0.387 ** | −0.018 | −0.981 *** | −0.478 *** | −0.741 *** |

| (0.164) | (0.131) | (0.222) | (0.116) | (0.171) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −21.800 *** | −14.837 *** | −18.617 *** | −16.828 *** | −18.073 *** |

| (2.705) | (1.997) | (4.792) | (2.500) | (3.811) | |

| Year/Industry | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Within R2 | 23,084 | 23,084 | 23,084 | 23,084 | 23,084 |

| F | 0.1819 | 0.038 | 0.1523 | 0.1515 | 0.159 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Q.; Lin, D. Top Management Team Stability and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Effects of Performance Aspiration Gap and Organisational Slack. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413972

Zheng Q, Lin D. Top Management Team Stability and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Effects of Performance Aspiration Gap and Organisational Slack. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413972

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Qiang, and Danming Lin. 2021. "Top Management Team Stability and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Effects of Performance Aspiration Gap and Organisational Slack" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413972

APA StyleZheng, Q., & Lin, D. (2021). Top Management Team Stability and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Effects of Performance Aspiration Gap and Organisational Slack. Sustainability, 13(24), 13972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413972