Components of DMZ Storytelling for International Tourists: A Tour Guide Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Role of Tour Guide

2.2. Storytelling and Travel Destination

3. Method

3.1. Research Questions

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Demographic Characteristics

4. Results

4.1. Being a DMZ Tour Guide

“There was a senior tour guide in my agency so I joined his tour several times. Once, I even recorded all of his talking, but you know, it’s like, it was really helpful for me because I had no experience with taking a tour.”(Interviewee E)

“Maybe my experience before being a tour guide. Because I was in the financial sector for 14 years and I was mostly in the customer relations. So, it was really helpful for me. I really try to determine the interests of the visitors and then make them satisfied.”(Interviewee E)

“But also, I have to know the basics, right? What is the Tunnel? When was it founded? What can you see from the pavilion and what does DMZ mean? Those very logical things, I learned them from books.”(Interviewee I)

4.2. Tour Guides’ Description of the DMZ

“First, usually, we talk about the DMZ or JSA tour, but officially, it’s not a tour. Officially it is called the DMZ and JSA Orientation and Education Program.”(Interviewee H)

“The DMZ and JSA is a peaceful coexistence area. Yeah, it will be a peaceful coexistence place. Not now, but someday, they will open the door. I think it’s the first step. No more control by soldiers. We can go freely, in the future. But these days, we don’t say JSA or DMZ, we say “Peace joint, Peace existence Area”.(Interviewee H)

“The blue houses! Because it’s the most famous picture of the DMZ. The line on the floor symbolizes hope and peace.”(Interviewee L)

“Seeing that one country is divided is amazing. Reactions are different. For us, it’s more the history that is fascinating, but Asians find it mysterious. When you visit Panmunjeom, you can see North Korean soldiers. It’s impressive (…) Technically speaking, you cross the border during the Panmunjeom tour. It’s thrilling. Also, when North Korean soldiers look at you, it’s huge and a little scary. And when there are Chinese tourists on the North Korean side, it’s quite funny. You are looking at each other.”(Interviewee J)

“I would like them to understand and remember that North Korea is a beautiful country. It’s not all about the dictator. It’s still a pretty country with beautiful landscapes.”(Interviewee J)

“Having North Korea next to us is an important part, even though we don’t really talk about it. But it’s actually reality to us, so to talk about our future, knowing about North Korea and what is behind the line, the relations.”(Interviewee E)

“It looks like a tourist attraction. Everybody laughs, smiles, takes pictures (…) It looks more like a tourist place, not the real DMZ.”(Interviewee D)

“Before the historical and cultural side of the DMZ, the site is about money first. For North Korea as well. And some tourists notice that.”(Interviewee J)

“Also, we need more time in the DMZ. In the end, not only for information, but there are many beautiful surroundings, natural surroundings. It’s been a no human being zone for 70 years. So, I hope that the place can become like a둘레길 (walking trail), like in Bukhansan Mountain. That place could be a good walking course or trekking course. But, I hope my guests can enjoy more nature on the DMZ course. But at this moment, it’s too short to enjoy the nature. So, maybe the next theme of the DMZ, I hope, is that people can enjoy the nature or eco-tourism. Because, I mean, the tension is already gone. If we change the theme to eco-tourism, it means that the tension situation is gone. That is my goal, or my hope.”(Interviewee B)

“But many people think only about war and missiles, they don’t know, at first, the richness of DMZ flora and fauna.”(Interviewee J)

“So, I can feel the division of my country. People say, when they go there, “Oh Korea is really divided by the line”, because they see the border line right? Some of them. And especially the building, some buildings are divided by the lines so they really feel like “Korea is really divided by the line.”(Interviewee D)

4.3. DMZ Storytelling Content

“I explain about the tour course. What stops we need to stop by. “There are 5 or 6 courses we need to stop by, so I explain the courses in detail.”(Interviewee B)

“From Seoul to Imjingak it takes one hour. I try to give them everything within 40 min.”(Interviewee A)

“So, DMZ is like divided, right? It’s a demilitarized zone. So, the key component will be the name, what it’s stands for, because many of the people don’t know that. And the second is how it was made, and third it is who was involved. And fourth is why it was made.”(Interviewee K)

“So, I always start with the Japanese colonial time. The later period of the Japanese colonial time. I always start with the history to tell them why we are divided like this: “It started from around 1945.”(Interviewee E)

“Like for example, the story of the thousands of cows that Hyundai CEO offered to North Korea. I learned it after several tours, not at the first one. And it’s a really important story that is related to North Korean History.”(Interviewee J)

“I spend more time talking about the reunification beliefs.”(Interviewee B)

“A lot of people ask me about president Trump, the relationship between North Korea and America. This kind of story (…) So it’s more the lives of people, relationships, opinions about North Koreans’ lives. It’s more like the reality of life (…) my experience, what I did, how many people I met. They want to listen my experience. So, I explain what I saw, the before and after, the changings of North Korean life. I try to explain that.”(Interviewee D)

“The last 20 min, I need to give them the regulations and all that. First of all, it’s the time. It’s the time. The most important. I think it is like “Now we are going into a military restricted area and there are regulations and all that. So, at every stop, we have a very limited amount of time and all that”. Number two is photo regulations. “The thing is that this regulation is always changing depends on the military authority. So sometimes, this place is ok to take pictures at, but not this place. This one, I will inform you again before we get off the bus.” Number three: “please do not disappear by yourselves.”(Interviewee A)

4.4. Factors That Influence Guides’ Storytelling

“So, if I take longer, the bus driver will get mad at me.”(Interviewee A)

“But some people, I mean some tourists, are not allowed to hear these stories. Sometimes soldiers, when they talk, underestimate some nations or a particular gender. Some are not well educated about the attitude they should have with tourists, about how to speak or explain history. They don’t know, before coming to JSA, about the guiding job. When they arrive at the Camp Bonifas, they don’t even imagine that they will become a tour guide. So that can happen. So, I need to explain what the soldier has said.”(Interviewee H)

“Because it’s a sensitive military zone, some places can be restricted all of a sudden, without notification. Sometimes there is a shutdown or some parts of the DMZ are closed. So, in that case, I change my storytelling according to that situation. First, I explain to them about the current situation and why we can’t visit some parts of the DMZ. Then, I have more stories about places we can visit.”(Interviewee G)

“Hmm political opinion matters. Yeah, so I think it depends… very old guides, what they are telling and what I am telling could be a bit different. Like, for example, I think the video we are watching at the DMZ is the Korean government view. It is also South Korea propaganda, I think. Yeah. So, political opinions matter, so some guides will describe North Korea as pure evil, but I don’t. I don’t say that. Well, I say that it’s a fact that they attacked us first. That is a fact, but I try to be more in the middle. I don’t just say, “They are evil, we are good”. I don’t say it like that.”(Interviewee C)

“But every day, actually, it’s a little bit different, because on some days, people listen very carefully and are so interested in my explanations, they ask me a lot of questions. So, it makes me happy and more energetic. I explain a lot in a more enthusiastic way. But some days, tourists are not very interested and some of them sleep or have no reaction. So, it makes me a little depressed because I’m a person, right? Haha. So, I try to explain the history, the facts, but sometimes I explain a little bit less than normal haha.”(Interviewee D)

4.5. Key Components of DMZ Storytelling

“Because we have various people coming from different countries, when I explain, I try to speak slowly in English to be sure that everyone can understand.”(Interviewee G)

“In short, I want to get them to use their five senses. That, I think, is more impactful. If I take them into the bunker, you know, if they can see a soldier and shake hands with him and talk to him. So it’s not just me talking. They use as many as senses as possible—sight, smell, hearing… If they use their senses, they can remember the story more.”(Interviewee F)

“I didn’t have any personal things to show to the tourists, but I would bring up some of my personal stories like… I lived very close to Paju, and in my room, I was able to listen to the North Korea radio. So, when I was young, I often listened to it. So, my mom was like… My mom is an old generation where they had an education of like “anti-North Korea”, right? So I was like listening to it out of curiosity, but my mom was like, “No, you shouldn’t be doing that. The KCIA will catch you and you can go to jail”. So, I told them those kinds of stories and people were very interested in them”.(Interviewee K)

“When we are in the train station, there is a Siberian map and while showing the map, I talk about the future of Korea and the past, as well as my own opinion and vision.”(Interviewee G)

“I do mix a lot of humor in the stories because the tourists are not here to take history lessons. They are tourists.”(Interviewee G)

“Showing our enthusiasm… It’s the most important thing when you guide. Managing to tell a story while making things interesting. Not being too soporific by only giving basic facts. I recently read a review that said that the guide was really enthusiastic, informative, and lovely until the end and they loved that.”(Interviewee J)

“If they don’t Google a lot or use YouTube, I can talk about some hidden stories (…) I want to tell some unusual stories. Everybody knows that North Korea has nuclear weapons. But there are some hidden stories, for example, after the Korean War was provoked, North Korean refugees were delivered by Americans. And during that time, five babies were born but they weren’t with their parents. So, actually, the American commanders who named the babies only knew the Korean word Kimchi. So, they called them Kimchi 1, Kimchi 2… and, afterwards, they got all adopted. It’s interesting right? Learning the daily life stories.”(Interviewee I)

“Well, if somebody asks me a question, I think I have to answer that. And, plus, I think it gives them a better understanding of what Korea is by telling them honestly. And they actually appreciate that. There are some tour guides who avoid that because they just want the tourists to be happy. They never talk about the negative side.”(Interviewee F)

“So, actually the tourists are very interested to see that. How the Koreans feel when they are at the DMZ area. And, actually, I told them that it was my first time seeing North Korea. People are so fascinated about that so that kind of helps, you know. It’s like giving them another kind of information.”(Interviewee K)

“I tried to deliver facts. If I wanted to give them opinionated thoughts, that would be my own opinion, my own story. I wanted to just deliver facts and if they have their own opinion, then that’s fine. Yeah, but I wouldn’t change the story.”(Interviewee K)

“So, I repeat the rules that the guide says. But the guide doesn’t guide all the way through once we are in the camp, for the Panmunjeom tour. There are also military police.”(Interviewee L)

“About Korean history… I think it may be difficult to understand and maybe not all foreign tourists are interested in listening to it. So, if I can, I try to make some comparisons between their own country’s history and culture and Korean history and culture.”(Interviewee M)

“I always bring some maps of the DMZ area, and now smartphones are very convenient. So, I let them see some pictures of North Korea.”(Interviewee D)

“Sometimes I need to bluff, but just in order to control them, in a manner.”(Interviewee A)

“So, we need to push them: “Let’s go! Time to go! No more pictures.”(Interviewee H)

“I really have to repeat again and again.”(Interviewee I)

“So, the meaning is not what I give, the meaning is how they take it.”(Interviewee A)

“Emotionally, we share our memories with them. If they knew some different things before coming to the DMZ that they figured out about the DMZ, I talk to them as a Korean, as someone who lives in a divided country, that’s my goal.” )(Interviewee B)

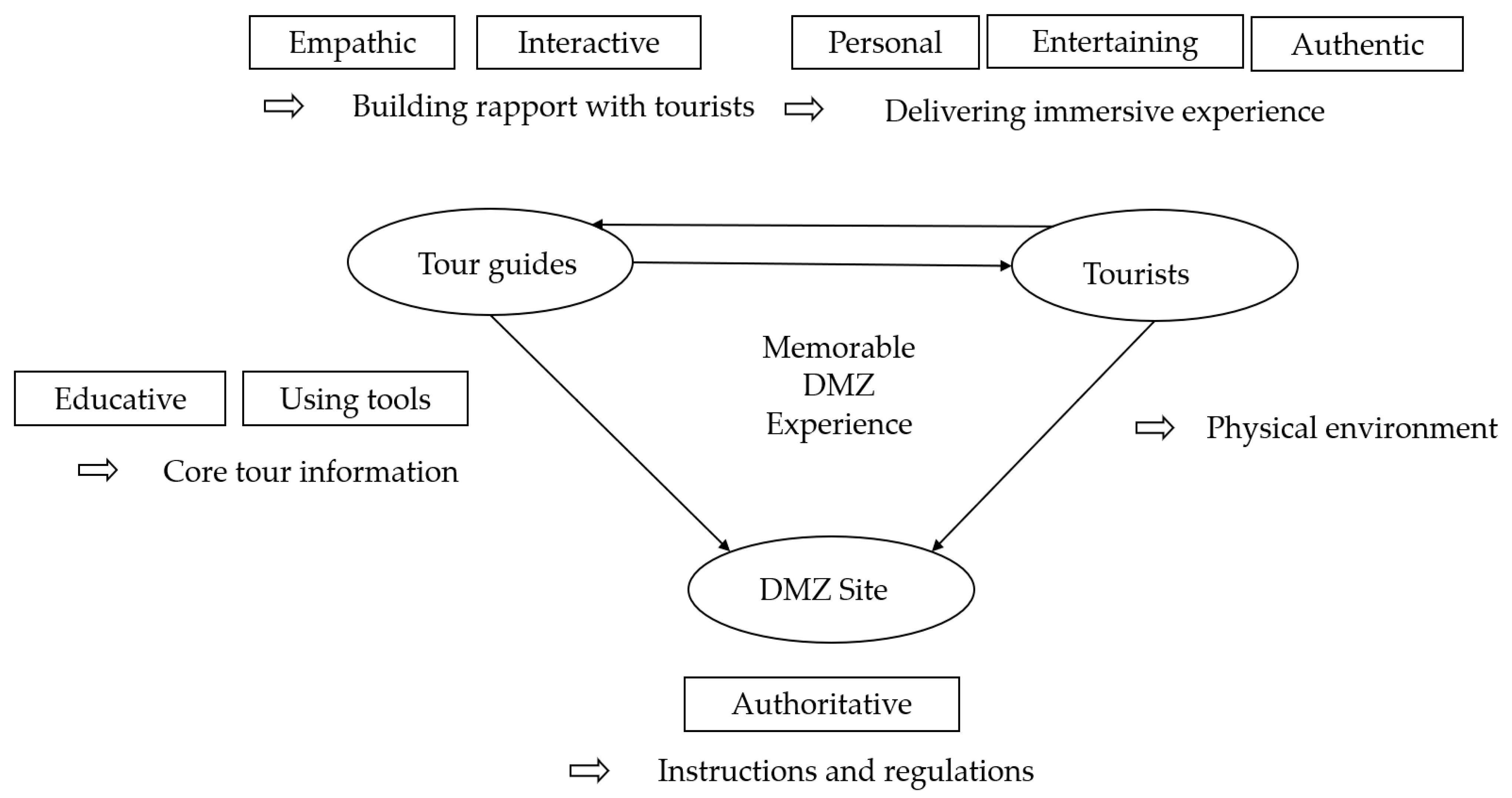

4.6. A proposed Conceptual Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Further Research Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ap, J.; Wong, K.K.F. Case Study on Tour Guiding: Professionalism, Issues and Problems. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronroos, C. A Service-Orientated Approach to Marketing of Services. Eur. J. Mark. 1978, 12, 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, A.; Goldman, A. Satisfaction Measurement in Guided Tours. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetıṅkaya, M.Y.; Öter, Z. Role of Tour Guides on Tourist Satisfaction Level in Guided Tours and Impact on Re-Visiting Intention: A Research in Istanbul. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2016, 7, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, J.-C. Taiwanese Tourists’ Perceptions of Service Quality on Outbound Guided Package Tours: A Qualitative Examination of the SERVQUAL Dimensions. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryon, J. Tour Guides as Storytellers—From Selling to Sharing. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2012, 12, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, L. The Exploration of the Memorable Tourist Experience. In Advances in Hospitality and Leisure; Chen, S.J., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2012; Volume 8, pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KTO. The DMZ Tour Course Guidebook. Available online: https://english.visitkorea.or.kr/upload/itis/enu/dmz_guide_eng.pdf. (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Bigley, J.D.; Lee, C.-K.; Chon, J.; Yoon, Y. Motivations for War-Related Tourism: A Case of DMZ Visitors in Korea. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W. The Visual Representation of Border Tourism: Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and Dokdo in South Korea. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Crompton, J.L. Role of Tourism in Unifying the Two Koreas. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Prideaux, B. Tourism, Peace, Politics and Ideology: Impacts of the Mt. Gumgang Tour Project in the Korean Peninsula. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Bendle, L.J.; Yoon, Y.-S.; Kim, M.-J. Thanatourism or Peace Tourism: Perceived Value at a North Korean Resort from an Indigenous Perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A. Nonmarket Values of Major Resources in the Korean DMZ Areas: A Test of Distance Decay. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 88, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Mjelde, J.W. Valuation of Ecotourism Resources Using a Contingent Valuation Method: The Case of the Korean DMZ. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.-J.; Scott, N.; Lee, T.J.; Ballantyne, R. Benefits of Visiting a ‘Dark Tourism’ Site: The Case of the Jeju April 3rd Peace Park, Korea. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y. A Study on the Development of the DMZ Tourism Merchandising which Use Storytelling. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Ventur. Entrep. 2015, 10, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberger, S. What Is a Tourist Guide? In World Federation of Tourist Guide Association (WFTGA); World Federation of Tourist Guide Associations: Vienna, Austria, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. The Tourist Guide: The Origins, Structure and Dynamics of a Role. Ann. Tour. Res. 1985, 12, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Q.; Chow, I. Application of Importance-Performance Model in Tour Guides’ Performance: Evidence from Mainland Chinese Outbound Visitors in Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, G.; Yarcan, S. The Professional Relationship between Tour Guides and Tour Operators. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.L.; Arnould, E.J.; Tierney, P. Going to Extremes: Managing Service Encounters and Assessing Provider Performance. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Lee, Y. A Study on Effect of Storytelling of Tourist Attraction on Tourists Attitude and Satisfaction. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2014, 26, 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Moin, S.M.A.; Hosany, S.; O’Brien, J. Storytelling in Destination Brands’ Promotional Videos. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassano, C.; Barile, S.; Piciocchi, P.; Spohrer, J.C.; Iandolo, F.; Fisk, R. Storytelling about Places: Tourism Marketing in the Digital Age. Cities 2019, 87, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, K. Making Museum Tours Better: Understanding What a Guided Tour Really Is and What a Tour Guide Really Does. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2012, 27, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, K.; Lu, H.; Lan, W. The Influence of the Components of Storytelling Blogs on Readers’ Travel Intentions. Internet Res. 2013, 23, 160–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Woodside, A.G. Storytelling Research on International Visitors: Interpreting Own Experiences in Tokyo. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2011, 14, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, H.G.; Kelley, S.W. A Story℡ling Perspective on Online Customer Reviews Reporting Service Failure and Recovery. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WOODSIDE, A.G.; MEGEHEE, C.M. Travel Storytelling Theory and Practice. Anatolia 2009, 20, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, M.F.; Mason, P.A. Transformative Tour Guiding: Training Tour Guides to Be Critically Reflective Practitioners. J. Ecotourism 2003, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilden, F.; Craig, R.B.; Dickenson, R.E. Interpreting Our Heritage, 4th ed.; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, A.H.; Mossberg, L. Consumer Immersion: A Key to Extraordinary Experiences. In Handbook on the Experience Economy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zátori, A. Exploring the Value Co-Creation Process on Guided Tours (the ‘AIM-Model’) and the Experience-Centric Management Approach. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carù, A.; Cova, B. Expériences de marque: Comment Favoriser l’immersion Du Consommateur? Décisions Mark. 2006, 41, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, A.S. Personal and Cultural Memories in War Tourism. Polit. Mem. 2013, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Second Edition: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Available online: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/basics-of-qualitative-research (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Bryant, A.; Charmaz, K. The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory: Paperback Edition; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M. Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRADY, L.M. Life in the DMZ: Turning a Diplomatic Failure into an Environmental Success. Dipl. Hist. 2008, 32, 585–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interviewee | Age | Experience | Gender | Nationality | Guide License | Experimented JSA Tour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 38 | 10 years | Male | Korean | Yes | No |

| B | 50 | 10 years | Female | Korean | Yes | No |

| C | 33 | 2 years | Female | Korean | Yes | No |

| D | 45 | 18 years | Female | Korean | Yes | Yes |

| E | 45 | 6 years | Female | Korean | Yes | Yes |

| F | 40’s | 5 years | Male | Korean | Yes | No |

| G | 40’s | 6 years | Male | Korean | Yes | No |

| H | 50’s | 9 years | Female | Korean | Yes | Yes |

| I | 36 | 10 years | Female | Korean | Yes | No |

| J | 35 | 2 years | Female | French | No | Yes |

| K | 32 | 2 years | Female | Korean | No | Yes |

| L | 38 | 5 years | Female | French | No | Yes |

| M | 33 | 7 years | Female | Korean | No | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bessiere, J.; Ahn, Y.-j. Components of DMZ Storytelling for International Tourists: A Tour Guide Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413725

Bessiere J, Ahn Y-j. Components of DMZ Storytelling for International Tourists: A Tour Guide Perspective. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413725

Chicago/Turabian StyleBessiere, Jeanne, and Young-joo Ahn. 2021. "Components of DMZ Storytelling for International Tourists: A Tour Guide Perspective" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413725

APA StyleBessiere, J., & Ahn, Y.-j. (2021). Components of DMZ Storytelling for International Tourists: A Tour Guide Perspective. Sustainability, 13(24), 13725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413725