1. Introduction

Mountain tourism is one of the most common types of tourist activities and appeals to tourists due to the spectacular landscapes, unique natural beauty, wildlife, fresh air, cultural landscape and various types of landforms that are available [

1,

2,

3]. The attraction for tourists relates to a wide range of activities and ways to spend leisure time [

4], including outdoor recreation, hiking, climbing, health and wellness activities, as well as the possibility to practice winter sports [

5]. Of all these, winter sports are among the most popular activities in mountain areas and are key factors for the booming development of mountain tourism in recent decades [

6,

7,

8].

Lately, winter sports have experienced an impetus both at a global and a local level, as people of all age groups and professions practice these activities [

9,

10]. Among winter sports, skiing represents a central element through which an entire industry has developed, acting as one of the most spectacular types of tourism activity [

11,

12,

13].

In this regard, to meet the demand, the specific infrastructure for practicing winter sports has experienced a similar evolution. Romania is no exception to this trend, taking into consideration its permissive landforms. Therefore, the ski area and ski slopes have undergone an upward evolution, both vertically (spatial evolution in the territory) and horizontally (quantitatively and qualitatively). Romania’s optimal geographic conditions have had an important contribution in this regard [

14], and orography has also played a significant role. Overall, 27.91% of the landform units are characterized by mountains and depressions, of which approximately 90% have heights suitable for winter sports of under 1500 m [

15,

16,

17].

The aim of the present study is to identify, quantify, assess and analyze five main indicators (number, length, width, level difference and slope) for the recreational ski slopes in Romania (homologated or not) at the levels of ski run, locality, county and country.

The ski slope is the fundamental unit, providing the basic cell for winter sports. In this study, we develop an understanding of the characteristic features of each ski run.

The locality was viewed in light of its role as a center of gravity for the flows of tourists looking to practice winter sports. Understanding the scale of the main indicators for the ski slopes at a locality level is crucial to conduct simulations, scenarios and proposals regarding the tourism carrying capacity for recreational ski areas, which is a factor that generates tourist motivation.

The county level proves to be significant in the profile analyses because it is a geographical, political, administrative, and sometimes decision-making element with major implications in terms of targeting all the flows to and from the county, including tourist flows.

An analysis of the main features of the ski areas in Romania offers a comprehensive image of their economic importance, as well as economic perspectives for the development of this sector.

In this context, analyzing the share of tourism turnover in total turnover and economic dependence can help to determine the evolution of tourism’s contribution to the total turnover of local economies.

The spectacular development of winter sports in Romania, also stimulated by many opportunities offered by European funding systems, requires an interdisciplinary approach that analyzes the main features of the ski area in Romania, as well as the adaptive capacity of local economies based on winter sports to increase the complexity of tourist functions to offset the changes imposed by climate change.

Romania is almost unanimous, highlighting its special quality, and has all the necessary conditions to become an important European tourism destination. By exploiting its true value, this unique potential can provide the basis for both the diversification and differentiation of Romanian tourism to successfully compete in different segments of the international tourism market. The potential value of tourism in Romania can also generate tourist activity that can act as one of the main engines of sustainable economic development [

18,

19,

20,

21]. As part of the tourist potential of Romania—viewed in a general sense—the mountainous area is distinguished because it has many positive characteristics that can be premises for the intensification of the tourist activity, especially during winter. The Romanian tourism authorities try to communicate abroad that Romania “is an authentic country, with intact nature and with a unique cultural heritage”, and the key attributes of the national tourist brand “Explore the Carpathian Garden!”—intact nature authenticity, unique culture and safety are strongly related to the Carpathian Mountains [

22]. This message matches perfectly the main attributes associated with the destination by foreign tourists who have visited it or who know persons who have visited it: authentic, rural, good hospitality and green [

23]. The mountainous area of Romania has 74,000 km

2 and concentrates 3 million inhabitants. These data correspond to a share of about one-third—31%—of the country’s total area. The Romanian Carpathians, both through their extensive expansion and central position, the general and altitudinal configuration, impose themselves as a basic component in Romania’s geographical and landscape structure. With the same importance, they are part of the tourist activity due to the richness and variety of their tourist potential [

24,

25]. Vanat [

26], in his yearly international report on snow and mountain tourism, stated that in Romania, “snow conditions can be very good through the end of March or even April”. This assertion is general and would require some refinements depending on the exposure, the runway, the altitude and the region concerned [

27,

28]. Romania has 44 ski resorts with about 150 ski lifts, of which 20% have been installed or renewed in the last 15 years. It is an attractive destination for foreign visitors as the prices are relatively low compared to most of Europe, and some ski slopes are lit for night skiing. However, lift permits are not considered to be cheap due to limited infrastructure and poor care [

29]. In Romania, it is estimated that ski resorts attract approximately 1.2 million visits per year.

Romania is not yet an important destination for tourism and winter sports. The highest number of domestic or foreign tourists arriving in the Romanian mountain resorts is reached in the summer months, regardless of the weather. The lack of diversification regarding tourist infrastructure, ski facilities below the international standard and poor performance of tourist services are probably some of the main reasons that lead tourists to choose other destinations [

30,

31]. It takes time to change, but Romania is making major efforts to develop these sectors that will positively influence the evolution of winter tourism. Although there are no substantial increases in accommodation capacity, ski resorts have found solutions to attract visitors by building ski slopes near cities [

32].

2. Materials and Methods

The necessary information for the current study was collected from the webpages of the National Authority for Tourism [

33], “i-Tour Schi”, “which is a national project to promote certified ski slopes across the country” [

34], and of other bodies involved in the promotion of ski slopes and weather conditions for practicing winter sports in Romania [

35,

36], capturing the existing facts at the end of year 2020. Data regarding the turnover were retrieved from the UB1365 Project and from

www.listafirme.ro [

37,

38]. The data were processed in Excel and ArcGIS 10.6. From a methodological point of view, the spatial analysis of the ski slopes in Romania was performed for each spatial point (ski slope, locality) and area (county, country) using the main indicators for the ski slopes: number, length, width, level difference and slope [

39,

40,

41,

42].

The turnover was used as an indicator for the analysis of the share of tourism in the local economy, thus, for all territorial administrative units in Romania with systematized ski areas, the share of turnover in tourism in total turnover of the local economy was analyzed for the period 2000 to 2018. This indicator shows the economic dependence of the analyzed localities on winter sports, with skiing as the dominant activity. Values below 24% show a low dependency, those between 25 and 49% indicate a high economic dependence and values over 50% denote a very high economic dependence.

Based on the average share of tourism contribution to the total turnover of the locality during the analyzed time interval, we decided to classify the localities into five distinct groups:

≤5% (Borșa, Gura Humorului, Muntele Mic, Păltiniș, Bâlea Lac, Râu de Mori, Joseni, Borsec, Câmpulung Moldovenesc, Mioarele, Valea Rece, Gura Râului, Azuga, Voineasa, Căpușul Mare, Mogoșa, Șuior-Baia Sprie Area, Vărșag, Cavnic, Dealul Cozla, Băile Homorod, Poiana Brașov, Izvoare, Bistrița, Pojorâta-Valea Putnei, Harghita-Băi + Miercurea Ciuc, Ciumani, Areas-Parâng-Petroșani, Malini, Feleacu, Ciucea, Straja, Toplița, Cârlibaba, Mădăraș, Izvorul Mureșului, Comandău, Vulcan, Jina, Cheile Butii, Întorsura Buzăului, Lunca de Sus, Rodna Mountains—Sant, Rânca, Luna Șes, Șugaș Băi, Drăguș, Ghelnița, Valea Mare);

Ranging from >5% to 10% (Areas-Muntele Băișorii and Băișoara, Bihor Mountains, Șureanu, Voievodeasa, Stâna de Vale, Mărișel, Piatra Fântânele, Ciceu, Vatra Dornei);

Ranging from >10% to 20% (Bran-Poarta, Arieșeni, Sinaia, Durău, Sovata, Praid, Bușteni, Moieciu, Covasna);

Ranging from >20% to 30% (Crivaia/Semenic, Slănic Moldova, Predeal/Pârâul Rece/Timișul de Sus);

>30% (Băile Tușnad, Gărâna—belonging to the commune Brebu Nou, Fundata, Gârda de Sus), the last ones are grouped as such given their small number.

We decided to use such a range-based classification because low levels of average weights were observed when analyzing the resorts, even in the most favorable cases. Additionally, we decided to take into consideration the groups with average weights exceeding 5% deemed to reflect a minimum acceptable threshold in this respect.

Afterwards basic descriptive statistics were used to detect some characteristics of the items belonging to each of the last four groups, such as mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Number of Ski Slopes in Romania

The number of ski slopes is a fundamental indicator which, together with other main indicators (length, number of localities having ski slopes, etc.), provides information related to the size of fragmentation, spatial distribution, perspectives and possibilities for economic capitalization of these elements that generate tourist motivation.

The analysis of the scientific literature show that the number of ski slopes has been a frequently used indicator from various points of view, such as the analysis of the potential of mountain tourist destinations focused on winter sports [

24,

25], the investigation of the economic efficiency of skiing in close relation with the distribution of infrastructure and thickness with the persistence of the snow layer [

27] and the impact on the environment [

43,

44].

In Romania, 242 ski slopes (of which only 205 were officially homologated) distributed in 78 localities from 20 counties were registered at the end of 2021.

The analysis of the number of ski slopes at county level has depicted five typical categories of such units: very large (7 counties, 161 ski slopes with a length of 168,259 m, distributed in 45 localities), large (3 counties, 42 ski slopes with a length of 40,317 m, distributed in 14 localities), medium (3 counties, 21 ski slopes with a length of 13,821 m, distributed in 8 localities), small (4 counties, 15 ski slopes with a length of 12,575 m, distributed in 8 localities) and very small (3 counties, 3 ski slopes with a length of 3764 m, distributed in 3 localities) (

Table 1).

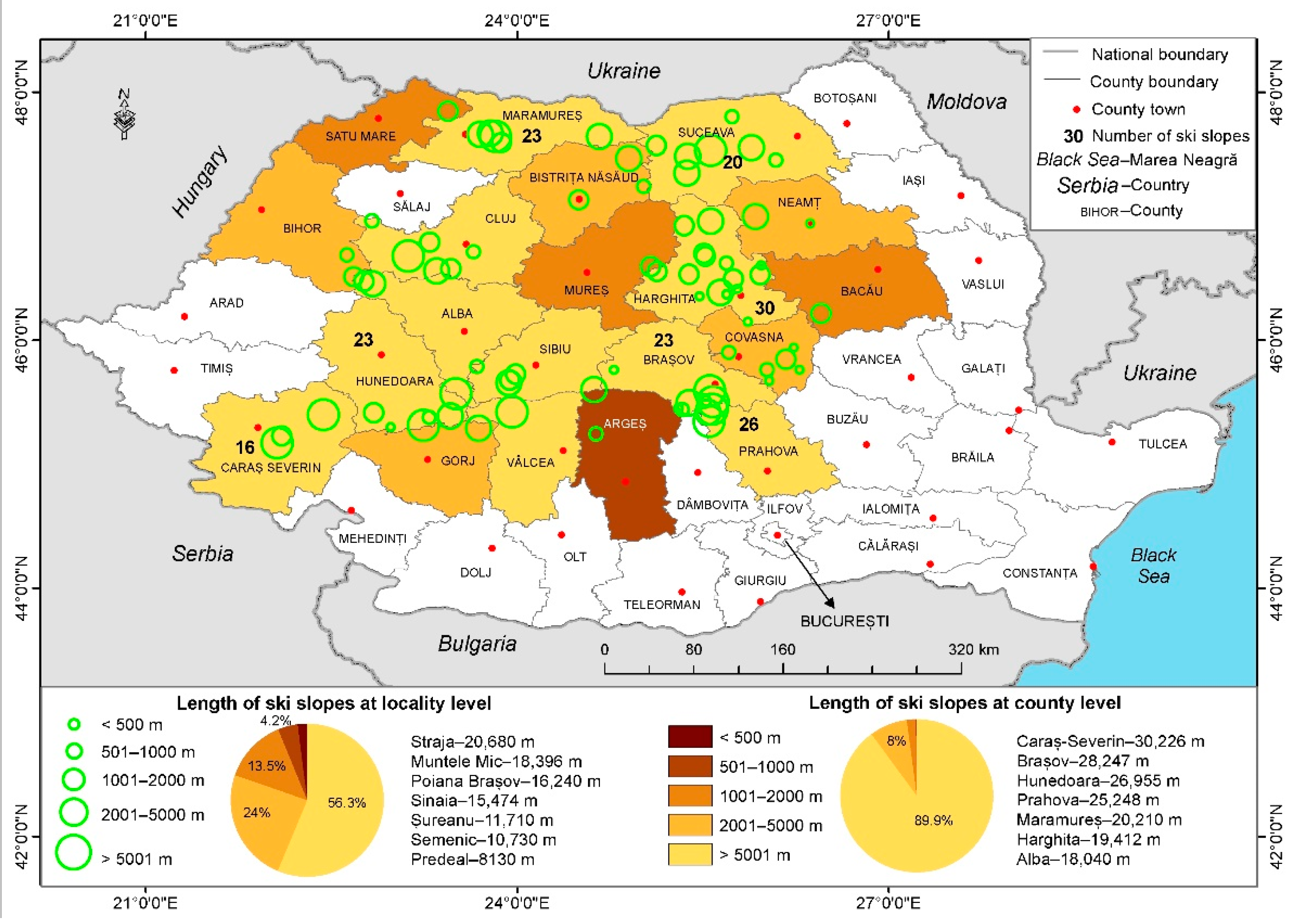

The highest number of ski slopes was identified in Harghita county (30 ski slopes), followed by Prahova (26 ski slopes), Brașov (23 ski slopes), Maramureș (23 ski slopes) and Hunedoara (23 ski slopes). On the opposite, Argeș, Bacău and Satu Mare counties can be found, each having one ski slope (

Figure 1).

The analysis of the number of ski slopes at locality level has delineated five typical categories: very large (Sinaia, 16 ski slopes with a length of 15,474 m), large (Staja, 12 ski slopes with a length of 20,680 m), medium (12 localities, 98 ski slopes with a length of 100,729 m, distributed in 10 counties), small (36 localities, 97 ski slopes with a length of 82,360 m, distributed in 15 counties) and very small (28 localities, 28 ski slopes with a length of 19,493 m, distributed in 12 counties) (

Table 2).

The highest number of ski slopes was identified in Sinaia (16 ski slopes), followed by Staja (10 ski slopes), Șureanu (10 ski slopes), Poiana Brașov (9 ski slopes), Cavnic (9 ski slopes) and Semenic (8 ski slopes). On the opposite side, 28 localities are situated, each having one ski slope (

Figure 1).

3.2. The Length of the Ski Slopes in Romania

The length of the ski slopes is important for the determination of both the status of winter sports resorts and the level of technical equipment. As in the case of the indicator —number of ski slopes, their length was also analyzed from the following perspectives. The analysis of the potential of mountain tourist destinations focused on winter sports [

24,

25], the investigation of the economic efficiency of skiing [

27,

45] and the analysis of its impact on the environment [

43,

44].

At the end of 2020, Romania had 242 ski slopes with a length of 238,736 m, distributed in 78 localities from 20 counties.

The analysis of the length of the ski slopes at county level has indicated four typical categories of such units: very large (11 counties, 210 ski slopes with a length of 214,670 m, distributed in 59 localities), large (5 counties, 27 ski slopes with a length of 19,002 m, distributed in 14 localities), medium (3 counties, 4 ski slopes with a length of 4514 m, distributed in 3 localities) and small (1 county, 1 ski slope with a length of 550 m, in one locality) (

Table 3).

The county with the longest length of ski slopes is Caraș-Severin (16 ski slopes with a length of 30,226 m), followed by Brașov (23 ski slopes with a length of 28,247 m), Hunedoara (23 ski slopes with a length of 26,955 m), Prahova (26 ski slopes with a length of 25,248 m) and Maramureș (23 ski slopes with a length of 20,210 m), while on the opposite, Argeș county is situated, having 1 one ski slope (Chili Slope from Mioarele locality) with a length of 550 m (

Figure 2).

The analysis of the length of the ski slopes at locality level has outlined 5 typological categories: very large (12 localities, 100 ski slopes with a length of 134,478 m, distributed in 9 counties), large (18 localities, 69 ski slopes with a length of 57,142 m, distributed in 12 counties), medium (22 localities, 42 ski slopes with a length of 32,310 m, distributed in 14 counties), small (17 localities, 22 ski slopes with a length of 11,566 m, distributed in 10 counties) and very small (9 localities, 9 ski slopes with a length of 3240 m, distributes in 5 counties) (

Table 4).

The locality with the longest length of the ski slopes is Straja from Hunedoara County (12 ski slopes measuring 20,680 m), followed by Muntele Mic, Caraș-Severin County (6 ski slopes measuring 19,396 m), Poiana Brașov, Brașov county (9 ski slopes measuring 16,240 m) and Sinaia, Prahova County (16 ski slopes measuring 15,474 m), while at the opposite end, the localities Comandău from Covasna County (300 m) and Ciceu from Harghita county (270 m) were situated (

Figure 2).

The analysis of the ski slopes in Romania has delineated five typological categories: very large (4 ski slopes with a length of 31,230 m, distributed in 4 localities, 3 counties), large (17 ski slopes with a length of 40,995 m, distributed in 13 localities, 9 counties), medium (51 ski slopes with a length of 69,452 m, distributed in 33 localities, 16 counties), small (107 ski slopes with a length of 77,642 m, distributed in 55 localities, 17 counties) and very small (63 ski slopes with a length of 19,417 m, distributed in 41 localities, 17 counties) (

Table 5).

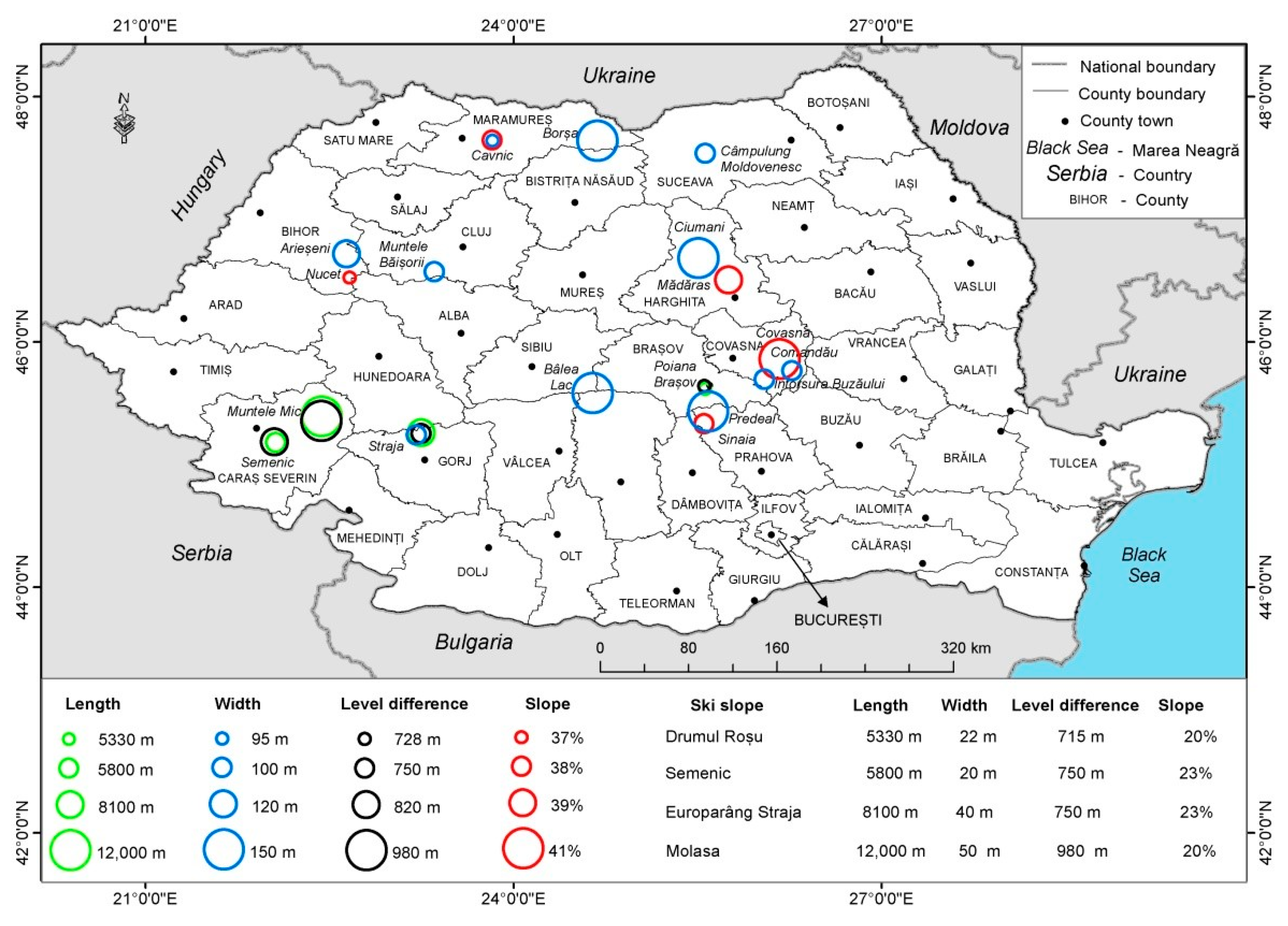

In terms of length, Molasa ski slope from Muntele Mic (12,000 m) ranked first, followed by the following ski slopes: Europarâng from Straja (8100 m), Semenic on Semenic Mountain (5800 m), Drumul Roșu from Poiana Brașov (5300 m), Telegondolă from Straja (3200 m), Subteleferic from Poiana Brașov (2860 m), Sulinar from Poiana Brasov (2820 m) and Rarău from Suceava (2850 m), while at the opposite end, Renul from Stâna de Vale (100 m), Icoană 4 from Cavnic (120 m), Telegondolă Northern variant from Voineasa (120 m) and Kicsi Sugo from Mădăras (140 m) were situated (

Figure 3).

3.3. The Width of the Ski Slopes in Romania

Slope characteristics such as width or steepness are necessary indicators that need to be taken into consideration when analyzing ski runs, especially when investigating possible risk factors [

46]. The width of the ski slopes is an essential indicator reflected in the degree of difficulty of the ski runs, on the one hand, and in the sizing of the accommodation capacity in correlation with the length and the correction index, on the other hand.

In this respect, the analysis of the width of the ski slopes in Romania, performed according to the correction factor [

47], has outlined 8 typological categories with width values ranging from the following: under 19 m (3 ski slopes with a length of 4266 m, distributed in 3 localities, 3 counties); 20–29 m (25 ski slopes with a length of 29,216 m, distributed in 19 localities, 11 counties), 30–39 m (44 ski slopes with a length of 37,945 m, distributed in 28 localities, 16 counties); 40–49 m (74 ski slopes with a length of 68,022 m, distributed in 45 localities, 18 counties), 50–59 m (46 ski slopes with a length of 54,479 m, distributed in 24 localities, 12 counties); 60–99 m (39 ski slopes with a length of 35,412 m, distributed in 22 localities, 11 counties); 100–149 m (6 ski slopes with a length of 3629 m, distributed in 6 localities, 5 counties); 150–199 m (5 ski slopes with a length of 5767 m, distributed in 4 localities, 4 counties) (

Table 6).

The widest ski slopes, of 150 m, were Cocoş Pârâul Rece (Predeal), Veresvirag (Ciumani), Teleschi/Prislop (Borșa), Curba de nivel (Bâlea Lac) and Balea Cascada (Bâlea Lac), while the narrowest were Drumul Tătarilor—B (Valea Putnei, 19.8 m), Cazacu Bretea Legatura Telegondola (Azuga, 19 m) and Ghețarul 3 (Gârda de Sus, 15 m) (

Figure 3).

3.4. The Level Difference of the Ski Slopes in Romania

The level difference of the ski slopes is a primary indicator that offers important information regarding the ski slopes’ rate and their degree of difficulty, as well as a central indicator used in the homologation standards for the ski slopes and leisure trails [

48,

49,

50].

The analysis of the level difference of the ski slopes in Romania has indicated 4 typological categories ranging as follows: under 50 m (32 ski slopes with a length of 10,759 m, distributed in 26 localities, 14 counties), 51–200 m (132 ski slopes with a length of 91,567 m, distributed in 55 localities, 16 counties), 201–500 m (65 ski slopes with a length of 84,018 m, distributed in 35 localities, 18 counties) and 501–1000 m (13 ski slopes with a length of 52,395 m, distributed in 8 localities, 6 counties) (

Table 7).

The ski slope with the highest-level difference was Molasa from Muntele Mic (980 m), followed by Semenic (820 m), Europarâng/Straja (750 m), Lupului/Poaiana Brașov (728 m) and Drumul Roșu/Poiana Brașov (715 m), while the lowest level differences were registered for Telegondolă Northern variant/Transalpina 6 (Voineasa, 6 m), Cazacu Beginners (Azuga, 10 m), Icoană 3 (Cavnic, 12 m) and Gondolă (Sinaia, 16 m) (

Figure 3).

3.5. The Slope of the Ski Runs in Romania

The slope represents the inclination angle of the ski run with direct implications on the determination of the degree of difficulty, the carrying capacity and the ski slope rate for practicing winter sports [

47]. As shown by previous studies, the degree of ski slope inclination is not a constant because it can be modified by a series of changes caused by the degree of soil stability [

51], the characteristics of the snow and the presence of ice [

52].

The analysis of the slopes in Romania, carried out according to the minimum approval criteria for the ski runs [

48,

49,

50], has emphasized 4 typological categories as follows: under 10% (18 ski slopes with a length of 10,586 m, distributed in 16 localities, 13 counties), 11–20% (95 ski slopes with a length of 73,994 m, distributed in 53 localities, 17 counties), 21–30% (91 ski slopes with a length of 100,414 m, distributed in 46 localities, 17 counties) and over 30.1–41% (35 ski slopes with a length of 38,841 m, distributed in 27 localities, 13 counties) (

Table 8).

The highest slope value was registered for Lorincz Zsigmond 2 from Covasna (41%), followed by Nagy Mihaly, Mădăras (39%), Rainer 2, Cavnic (38%), Târle, Sinaia (38%) and Special Piatra Grăitoare Slope from Bihor Mountains (37%), while the lowest level differences were registered for Telegondolă North/Transalpina 6, Voineasa (1.92%), Drumul Tătarilor—A, Valea Putnei (5%) and Clăbucet school, Predeal (7%) (

Figure 3).

3.6. The Economic Dependence of Locations on Winter Sports

Previous studies have demonstrated the impact, either positive or negative, generated by tourist activity on local communities and their economy on various directions: economic, social, cultural and environmental. However, these types of impacts are different depending on the type of tourist activity, destination and context [

53]. However, the tourism industry is fundamental for the economic and sustainable growth of societies [

54]. Worldwide, where landforms and climate are favorable for practicing winter sports, the winter tourism industry contributes significantly to the local economy due to an increased added value and employment in related activities [

55]. According to the World Tourism Organization [

56] the Tourism Direct Gross Domestic Product in Romania, which is one of the most analyzed indicators used to measure the contribution of tourist activity in the total economy, has registered an ascending tendency over the last years.

The analysis of the share of the turnover in tourism in the total turnover of the localities with ski slopes highlights the low number of localities that are highly or very highly dependent on skiing; 11 localities register a general trend of increasing values. For the rest of the localities, the economic dependence of the local economies on winter sports is low (

Appendix A-

Table A1).

Unfortunately, but not at all surprising, the tourism contribution to the overall turnover of the related local economies registers, in most of the cases, insignificant values. The long list of resorts belonging to the first group, with average weights between 0% and 5%, confirms this aspect. More exactly, specific data were collected for about 49 units out of a total of 73.

The average values for the other 24 are all consistently spread upward up to the threshold of 5%, but without exceeding 57.68%: up to 10% for 8 resorts, up to 20% for 9 resorts, up to 30% for 3 resorts and over 30% for 4 resorts, despite some other higher isolated values reaching a maximum of 99% (Gărâna−2001) registered in some years, mainly for resorts ranked in the two best placed groups. Specifically, for the group with average values ranging from 5% to 10%, we obtained the statistical results presented in

Table 9.

The results indicate extreme values for each unit across years, an aspect confirmed by the standard deviation levels, the minimum value being the null one, safe for two of them (Voievodeasa and Vatra Dornei) and the last ones with extremely low levels as well, of 2% and 3%; therefore, basing the budget on tourism might destabilize the local economy, so a prudent approach is recommended in such case.

The asymmetry of the central tendency is mostly positive for the sample from this group, showing that the higher values, with a stronger impact on the average, are reduced as the number within the overall range of values, a fact outlined more than in any other case by Stâna de Vale with a maximum of 71% (in 2000) and a minimum of 0% (in 2014, 2017 and 2018).

The statistics for the group with average values ranging from 10% to 20% are presented in

Table 10.

Additionally, significant differences between the minimum and the maximum values across years are present for each unit, as also clearly reflected by the standard deviation levels, while the null value is registered this time only for Arieșeni (in 2000 and 2001). Yet, Bran-Poarta, Bușteni and Moieciu register minimum values lower than 5%; this stands for the high volatility of the benefits expected in terms of contribution to the turnover in the case of related local economies.

For this sample, the asymmetry relating to the central tendency is bilateral (either positive or negative), both higher and lower values depending on the analyzed unit, with a higher impact on the average weight.

The group with average values ranging from 20% to 30% provided the basic statistics presented in

Table 11.

Although we analyzed a group with an increased, low to medium, average contribution, the extreme values continue to be surprising. Crivaia/Semenic fluctuates across a period of 19 years from 0% to 60% and Slănic Moldova from 7% to 58%, Predeal/Pârâul Rece/Timișul de Sus being the only one with more acceptable differences between the lowest and the highest registered values.

The last group considered in our research, with average values exceeding 30%, therefore including resorts for which tourism represents a more significant contributor to the well-being of the local economies, generated the descriptive statistics rendered in

Table 12.

Unfortunately, this group does not deviate significantly from the already discussed ones as concerns the variation of values across years for the units contained therein. However, the minimum lower bound encountered in the currently analyzed group amounts to 10% (Gărâna), thus representing a low but acceptable level, while the upper values range from 53% (Gârda de Sus) to 99% (Gărâna).

4. Conclusions

The analysis of the indicators from the current study provides both a detailed image (at ski slope and locality level), as well as an overall picture (at county and country level) regarding the spread of winter sports practice in Romania. Our research data and results can be used to initiate and conduct other studies with direct theoretical and practical impact.

The obtained results are part of various studies on the development of territorial systems with a specific function, characterized by exposure to systemic risks which need permanent structural interventions to ensure a sustainable development [

57,

58,

59,

60].

Due to its situation and geographical conditions, Romania benefits from optimum circumstances to develop winter sports. In this respect, amid the growth of demand, the ski slopes seen as areas of convergence for those who practice winter sports have witnessed a steady evolution both quantitatively and qualitatively. The quantitative evolution, at a spatial level, has targeted the increase in the number, length, comfort and equipment of the ski slopes.

Therefore, the analysis of the main indicators of the ski slopes in Romania has pointed out the existence of 242 ski slopes with a length of 238,736 m, distributed unevenly in 78 localities from 20 counties.

The counties with the most ski slopes were Prahova (26 units, 25,248 m), Harghita (23 units, 19,412 m) and Brașov (23 units, 28,247 m), while the counties with the longest ski slopes were Caraș Severin (30,226 m, 16 units), Brașov (28,247 m, 23 units), Hunedoara (26,955 m, 23 units) and Prahova (25,248 m, 26 units).

The localities with most ski slopes were Sinaia (16 units, 15,474 m), Straja (12 units, 20,680 m), Șureanu (10 units, 11,710 m), Poiana Brașov (9 units, 16,240 m) and Cavnic (9 units, 7770 m), while the longest ones were registered in Straja (20,680 m, 12 units), Muntele Mic (18,396 m, 6 units), Poiana Brașov (16,240 m, 9 units) and Sinaia (15,474 m, 16 units).

The longest ski slopes were Molasa from Muntele Mic, Caraș-Severin County (12,000 m), Europarâng from Straja Hunedoara County (8100 m), Semenic from Semenic Mountain, Caraș-Severin County (5800 m) and Drumul Roșu from Poiana Brașov, Brașov County (5330 m). Each slope is also characterized by a range of specific quantitative and qualitative features.

Although the quantitative analysis is restrained to a primary approach, as mentioned in the methodological part, given both the specificity of the data and the aim of this research, we can ascertain that there is no pronounced differentiation within and between the considered groups, all demonstrating a high volatility in terms of the evolution of tourism’s contribution to the overall turnover of the related local economies due to a large variety of reasons that do not fall under the aim of this paper. It is precisely why, in addition to the overall rather low average benefits, such uncertainty that brought a prosperous evolution to the mentioned economies should inform the entitled entities (local authorities and, going upstream, regional and national authorities) about the urgency of taking steps into the right direction, identifying alternatives for a constant, stable and reasonably consistent provision of such benefits.

The investigation on the dependence of local economies on winter sports and the role of winter sports in the sustainable development of tourism in Romania requires complex research, which aims for both the development potential of winter bonuses as well as the exploitation of other resources [

61,

62] based on which to ensure an optimal complexity of the local economy.