1. Introduction

Modern cities tend to over-develop and become overpopulated, forming compact urban structures. This gives rise to fire risks, as fires can spread easily between connected buildings. It also presents a sanitation issue, as direct sunshine is not secured through adjoining buildings. Securing sunshine in an indoor space reduces the psychological closeness and pressure that residents feel and provides appealing views. Sunlight is also essential for a pleasant and clean life in terms of ventilation and sterilization. To prevent fire risks, the Building Act of Korea’s urban planning government office required buildings to feature a minimum setback distance (a minimum requirement of open space between buildings and structures) in between them to improve fire safety and ensure a more pleasant environment for residents. Many studies have proven that securing setback distance between buildings is a significant variable in preventing fires from spreading [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Moreover, side setback areas have been proven to be a key factor for building environments within residential areas, as they facilitate access to sunshine and ventilation [

5,

6,

7].

Recently, side setback areas between buildings have been used for specific purposes, such as outdoor retail or market spaces. This is in line with the trend of urban regeneration, in which small, in-between unused and neglected spaces are created into productive spaces, since supersaturated cities do not have the option of developing large areas of land. In particular, as commercial facilities penetrate the lower levels of buildings in general residential areas (in what is considered commercialization), the adjoining vacant lots within building sites, such as side setback areas, are also becoming commercialized. Stores on the lower levels of adjoining buildings mostly use side setback areas as their outdoor sales space. They sometimes set up small pocket gardens or separate pop-up stores.

These structures are illegal, involving the unauthorized extension or occupation of vacant lots without permission. Structurally speaking, establishing facilities within side setback areas may increase the risk of fires spreading, as the buildings on both sides may become close and connected. In other words, in terms of health management by securing sunshine and fire safety, which is the basis for policy on creating side setback areas, the establishment of other facilities within side setback areas can be considered a risk factor [

8].

Alternatively, some studies argue that various activities using side setback areas may vitalize particular regions. Researchers perceive side setback areas as small unused spaces that are distributed in various parts of the city and serve as a medium for connecting individual urban elements [

9,

10,

11]. It has also been pointed out that these side setback structures address the demand for finding new customized functions considering the limitations of the surrounding areas [

12,

13]. They have also claimed that the existing regulations that unconditionally neglect and prohibit the use of side setback areas are irrational in dense urban centers. Furthermore, they are not public open spaces but private lands and, thus, lead to property rights violations.

Nonetheless, it is clear that the setback distance between buildings is still an indispensable physical element for safety and sanitation. As long as there is a plan to safely use side setback areas without damaging their current purpose, unused space in dense and saturated urban centers can be used wisely. Therefore, this study sets specific guidelines for the use of side setback areas to obtain a common ground between public regulations and the demands of urban residents. This approach is an attempt to reflect on urban space utilization behavior in urban management planning, based on the voluntary demands of urban residents, which raises the need to reestablish existing systems.

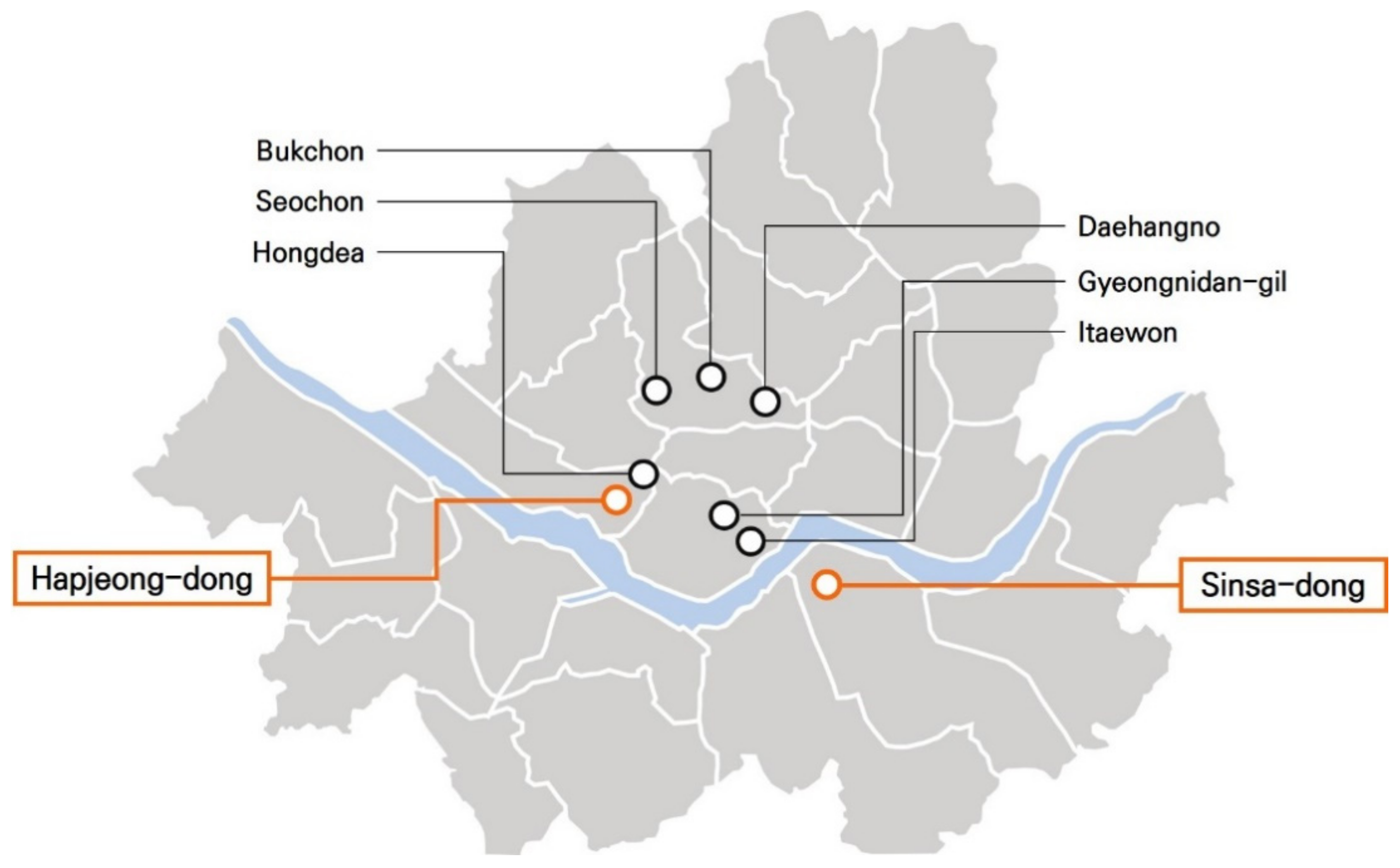

Seoul, which is a typical example of a modern megacity in Asia that is overdeveloped and overpopulated, was selected as the analysis site. According to the zoning system in Seoul, there are regulations on “forming setback distances from the boundary lines of adjacent lots” in residential areas, pertaining to fire safety or access to sunshine. However, this law has not yet been applied to commercial areas. In the 2010s, some residential areas of Seoul showed signs of commercialization, in which commercial facilities penetrated the lower levels of buildings situated on certain streets. Stores on lower levels conduct commercial activities by using the side setback areas of the buildings. This is currently an illegal act that is subject to regulation, but store owners and pedestrians respond positively to the use of this space [

13,

14]. Conflicts between the system and users lead to repetitive acts of closing, demolishing, and installing these spaces, deteriorating the quality of the street environment. As such, Seoul city clearly reveals the need to establish relevant guidelines and reform the system and is, thus, suitable for analysis in this study.

The purpose of this study is to establish a new direction for utilizing side setback areas for fire safety in Seoul. The specific contents and procedures of this study are as follows. First, the relevant acts and systems in Korea are reviewed, as well as the overseas policies related to the creation and regulation of side setback areas. The scope of side setback area utilization is also assessed. We also conducted a literature review on two aspects: regulating and permitting the use of space in terms of fire safety.

Next, we selected specific sites in Seoul and conducted a case analysis. First, we examined the utilization status of side setback areas of buildings and conflicts existing within the system. Next, we surveyed and interviewed relevant public officials and experts on the management and use of these spaces. Here, we conducted in-depth interviews with a few participants so that they could provide specific system reform measures. Lee and Park [

13] conducted a survey on the demand for system reform in using side setback areas among users and store owners and discovered that there was a high demand. It was also proven that, in terms of street landscape, using side setback areas increases vitalizing factors such as street diversity and openness [

14]. With discussions already complete in the private sector, this study is at the stage of establishing the direction for system reform to reach a social consensus that includes the public sector.

Finally, we intended to establish system reform measures and construct guidelines for using side setback areas rationally while meeting the purpose of their establishment (focusing on sanitation/fire hazards). This study is significant in that it establishes a new direction for urban architectural structures in sustainable cities by meeting the changing needs of urban residents. In this process, we focused on improving the structural safety of these spaces against fire, which is a risk factor in supersaturated urban spaces.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Review of Legislations Related to the Formation of Building Setbacks

In general, side setback areas are formed through the process of limiting the actions and development density of buildings. Building-to-land or floor area ratios are applied differently, depending on special-purpose areas and districts, which determine the size and layout of buildings and affect the establishment of remaining vacant lots within the land, excluding the building area. Moreover, the Building Act and other relevant laws regulate the development density and form of buildings depending on their purpose, height, and area and, in some cases, there are conditions such as securing privately owned public spaces for public use. Some countries require separated vacant lots between buildings as well as road and land boundary lines to facilitate evacuation and passage in the case of fire.

In Seoul, the subject of this study, construction restrictions are informed by legislation from the National Land Planning and Utilization Act, the Building Act, the Act on Fire Prevention and Installation, Maintenance, and Safety Control of Firefighting Systems, the Management of Outdoor Advertisements Act, the Promotion of Outdoor Advertisement Industry, and the Parking Lot Act, as they are all related to the formation and use of side setback areas (see

Table 1). Additionally, there are vacant lots within the building site that are part of the process of maintaining a setback distance from adjacent buildings. It is advisable to empty the front and side spaces of buildings that are in contact with the street among vacant lots for purposes such as evacuation, safety, and sanitation.

Singapore, a large city-state in Asia with a similar urban structure, designates four types of outdoor display areas (ODAs) related to fire safety: non-roofed-over ODAs detached from buildings, roofed-over ODAs detached from buildings, ODAs along covered walkways, and ODAs with extended awning/canopies (see

Figure 1). ODAs are vacant lots within building sites but are legally permitted for use, which is different from Seoul. However, there are specific items of fire safety considered applicable to all ODAs, such as bans on open-flame activities and encroachment onto fire engine accessways or access roads, and the mandatory installatios of fire extinguishers within 15 m of roofed-over ODAs [

15].

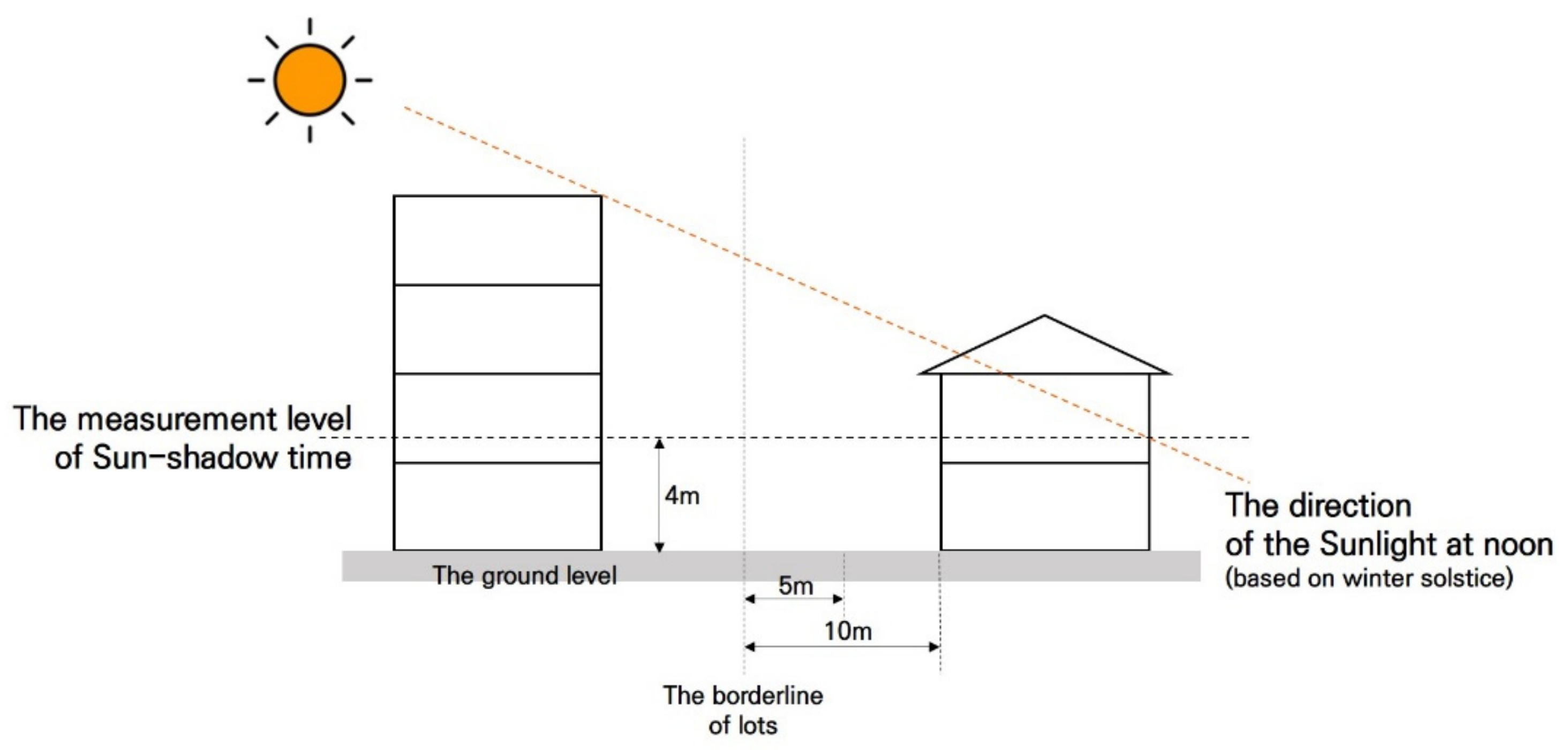

Another Asian city, Tokyo, Japan, also sets regulations on setback distance. However, unlike Singapore, Japan maintains a distance between buildings to guarantee the right to sunlight, rather than for the purpose of safety against fire. There must be a setback distance between roadside buildings due north, considering the angle and direction of sunbeams at noon.

Table 2 is the right-of-light legal regulation standard article 56(2) of the Japanese Building Standards Act [

16,

17]. This regulation secures sunlight for surrounding areas by stipulating the light generated by high-rise buildings within a residential area, within a certain period of time. In

Figure 2, for example, in the mid-/high-rise residential area, a distance of 5 to 10 m from the adjacent building, is required to allow enough sunlight (about 3 h to 5 h of sun-shadow time reference

Table 2) to enter the building at noon. It should be noted that, when designating the sunshine time standard, guidelines on sun-shadow regulations for each use are established based on preliminary surveys so that each local government can autonomously apply them considering the regional characteristics and context (see

Table 2).

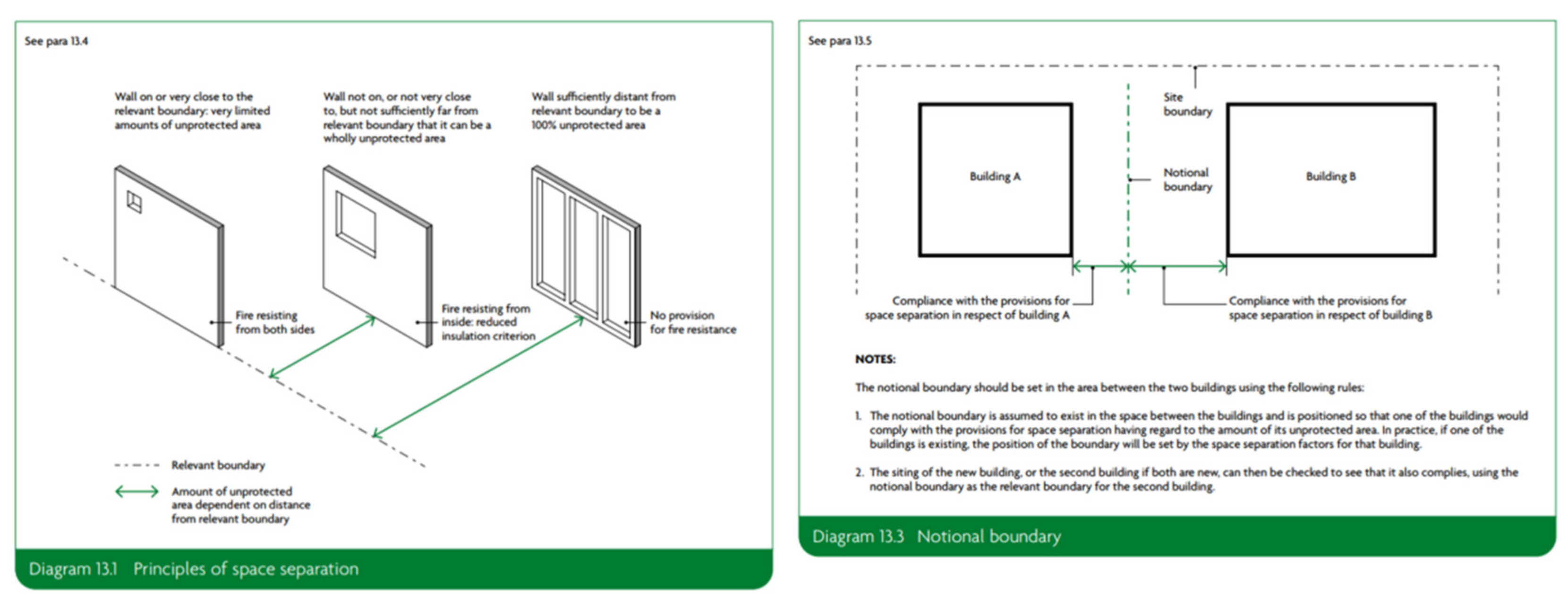

As in Asian countries, various Western cities also create setback distances between buildings to prevent fires or to secure sunshine. The UK has established detailed guidelines to prevent fires from spreading to nearby buildings, according to regulations that establish distances between buildings to prevent fire [

18,

19]. According to the guidelines, it is important to set the distance by calculating the boundary distance between buildings.

Figure 3 is part of the building regulations for fire safety in the UK. The notional boundary is assumed to exist in the space between the buildings, and is positioned so that one of the buildings complies with the provisions for space separation, with regard to its total unprotected area [

18]. In practice, if one of the buildings has already been established, the position of the boundary is set by the space separation factors for that building [

19]. Although the exact value of the separation distance is not determined, the amount of unprotected area dependent on distance from the relevant boundary is determined according to the degree of fire resistance of the wall material, which is known as the principles of space separation.

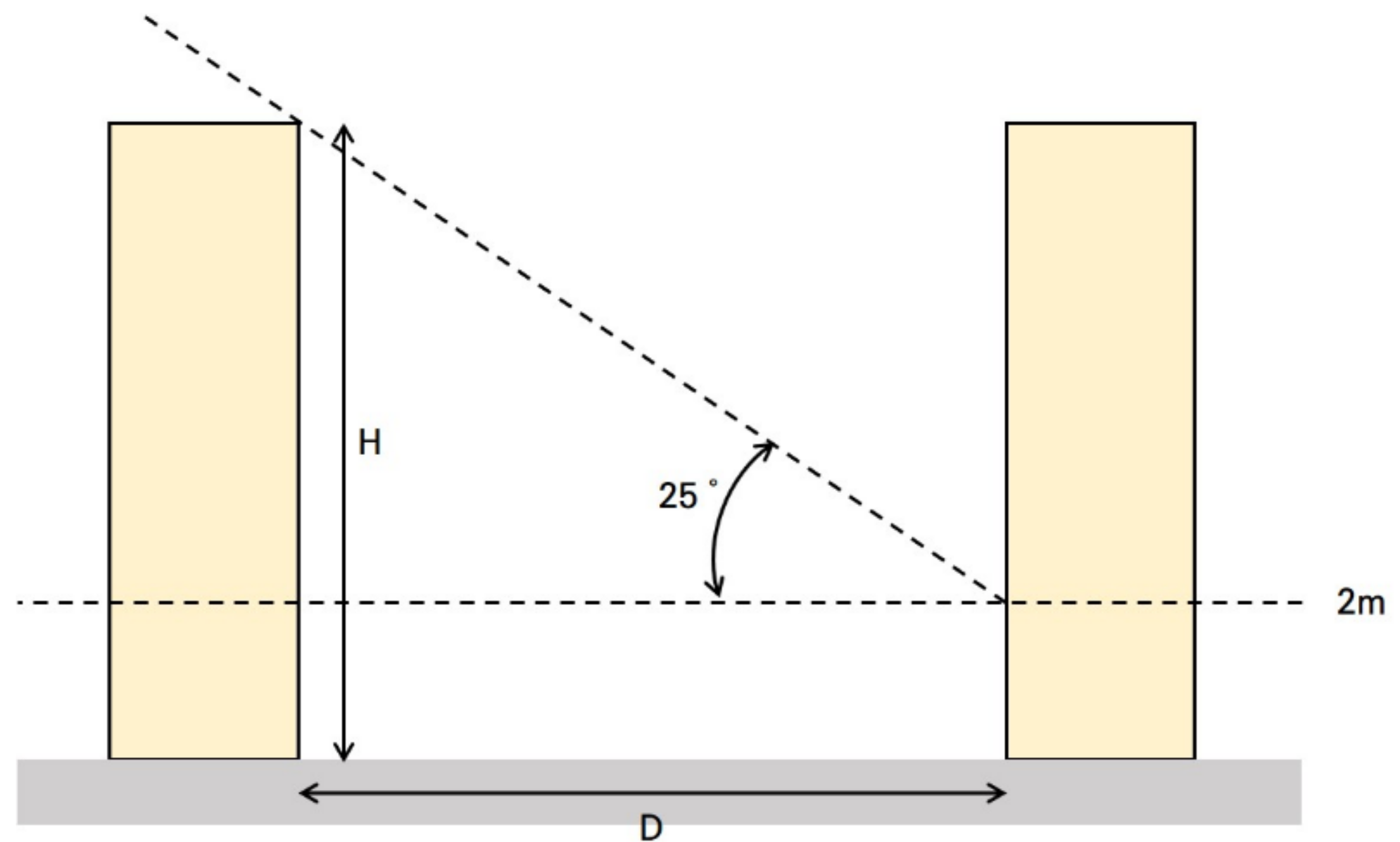

The UK also has concerns over the right to light and guarantees the right to sunlight by addressing the formation of setback distance in various clauses (see

Figure 4) [

20,

21,

22]. In general, the angle of light entering a building should be 25 degrees, and the gap between buildings should be wide enough that the light can shine through a 2 m-high window. In addition, to obtain permission to build, the building’s sunshine is measured and determined based on the design plan and detailed criteria such as the Building Research Establishment (BRE) guidelines and the British Standard (BS) Code to determine in detail the design direction related to lighting in both existing and new buildings.

After reviewing the grounds and regulations for forming setback distances in various other cities and nations, we surmised a few implications that must be applied in Seoul. First, detailed guidelines must be established to guarantee fire safety. Singapore categorized the physical form of side setback areas into four types and provided suitable fire prevention guidelines for each form. Because buildings are already equipped with escape routes and firefighting facilities, user safety is guaranteed even when the setback area is occupied and used. The UK set detailed rules for building materials and layouts to prevent the spread of fires to adjacent spaces. In other words, instead of unconditionally forming side setback areas, they set guidelines for various elements of planning to exclude risk factors while maintaining the utility value of these spaces.

Next, it is necessary to consider locational characteristics when considering sunshine. Both the Japan and the UK guidelines make distinctions depending on the building location and regional characteristics while calculating the distance so that access to sunlight is ensured. Japan considers the use of these areas and decides whether to apply such regulations after considering whether sunshine can be secured. In Seoul, on the other hand, side setback areas are used in residential areas that are becoming commercialized. In other words, buildings have certain uses for which urban residents do not necessarily need sunshine. Therefore, it is necessary to individually review the need for side setback areas for securing sunshine in each special-purpose area.

2.2. The Scope of Side Setback Areas (Definition of the Research Subject)

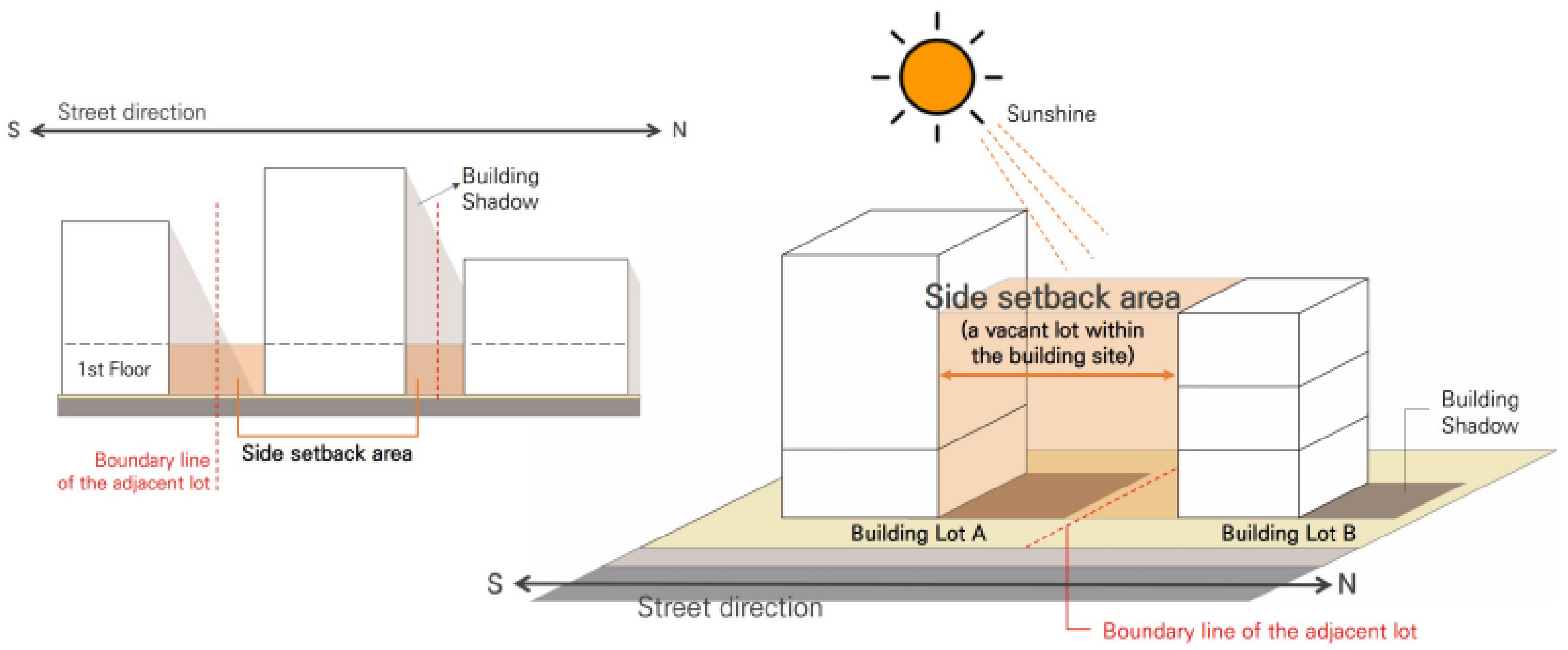

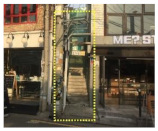

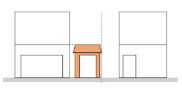

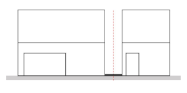

In the previous section, the legislation on side setback areas was reviewed based on different cities and cases, and we defined the specific scope of “side setback areas” to be analyzed in this study (See

Figure 5). First, a side setback area is a vacant lot within the building site and is a private area. However, it must be formed depending on public purposes, and because it is connected to a public walkway between buildings, it is defined as a semi-public area that includes public functions as well.

Second, side setback areas connected to public walkways are used by expanding the use of the lower levels of the building or by installing facilities, thereby showing high spatial utility. On the other hand, the fronts of buildings offer limited space and is considered only in terms of expanding the walkway, and thus the space cannot be independent of the store. Therefore, this study limits the side setback area to the side space of the building and defines it as an in-between space secured by the distance from the adjacent lot.

2.3. Literature Review on Side Setback Areas

There are two academic approaches to side setback areas: (1) studies analyzing side setback areas as significant physical factors that can prevent hazards such as fire, and (2) studies considering its utility value as a small idle land that is discarded.

The first perspective focuses on determining physical factors that prevent building fires as an urban problem. These studies approach research questions in terms of their architectural structure. Himoto and Tanaka [

1] explored solutions for the urban fire-spread model based on physics. In the process of analyzing various factors affecting heat transfer in fires between adjacent buildings, they proved that the “separation of buildings,” such as side setback areas between buildings, plays a significant role. Cheng and Hadjjsophocleous [

2] conducted 12 fire experiments and calculated the optimum setback distance between buildings considering time as a factor.

Cicione et al. [

4] also experimented on unauthorized squatter settlements from a similar perspective, and Yun et al. [

8] did so similarly on traditional markets, discovering that setback distance is the most important factor in minimizing the spread of fires. Nishio et al. [

3] tested horizontal fire spread to prevent their spread in high-density residential areas in Japan. Since it is already assumed that the setback distance is very short, they presented insulation systems and materials to minimize the spread, presuming that there is a high risk.

The second perspective includes studies presenting side setback areas as unused spaces with utility value. Shojai et al. [

5] examined the characteristics of side setback areas in residential districts in Japan. They argued that side setback areas adjacent to public walkways are public in nature and are, thus, perceived as open space by pedestrians. Moreover, since they are located between buildings, they are perceived as spaces that facilitate various events in streets and increase the frequency of social contact [

11]. Some Western researchers defined the empty space between buildings as in-between spaces [

9,

10,

11,

23,

24,

25,

26]. This is not just an outdoor space, but a special space whose significance depends on how it is used. Ubeyrathne [

26] termed small urban units such as side setback area, which are disappearing due to indiscriminate development, urban pockets. According to his research, urban pockets are physical components of cities that provide social and cultural experiences depending on how they are used.

Side setback areas can be used in two ways. First, side setback areas adjacent to residential buildings within a residential district can be used as green spaces or air shafts, which affects housing prices and satisfaction with the residential environment [

5,

6,

7,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Kilnarova and Wittmann [

30] compared the closed courts in the urban block from the 19th central and the open spaces in the housing estates constructed under socialism in the 20th central. They proved that the configuration of open spaces between residential buildings affects the quality of environment, and the quality of life of local residences. In addition, residents are highly aware of large green open spaces in terms of sustainability.

Meanwhile, studies on commercial districts have pointed out that side setback areas in commercial districts reduce street comfort due to negligence [

12,

13,

14,

31]. Therefore, it is necessary to be aware of neglected side setback areas and provide them with more active roles, using them as an element to vitalize the city. This study focuses on the research by Lee and Park [

13]. These authors categorized the use of side setback areas in commercialized streets, as residential areas in Seoul are becoming more commercialized. A satisfaction survey on users and store owners in each category showed that the participants were satisfied with the use of space. Participants also claimed that system reform is needed and that they were willing to use side setback areas at a cost, if necessary. The researchers argued that the right to sunlight is not necessary for commercialized roadside buildings and side setback areas, and with variable and flexible installations, facilities can be easily removed, and people can evacuate quickly in the event of a fire. Thus, side setback areas must be used for various purposes, instead of being neglected.

From another point of view, Mahdzar [

32] analyzed the characteristics that commercial streets should include to activate outdoor activities for people in Malaysia. As a result, it was revealed that densely populated stores have a variety of interfaces with impressive physical characteristics, and the space between buildings is a potential place to play such a role.

In summary, studies from the first perspective argue that it is necessary to form setback distances in dense urban spaces, implying that certain requirements must be met, such as escape routes for fire safety. They also imply that it is important to use non-flammable materials when the side setback areas are too small or when installing certain facilities. Studies from the second perspective focus on the possibility of bigger urban problems if side setback areas are neglected and prove that a region’s vitality increases by using those spaces. In particular, Lee and Park [

13] discovered the positive effects of using side setback areas on urban residents.

Studies from these two perspectives present different arguments about the same type of space. However, it is necessary to consider that the utility of a side setback area is nonetheless important and that there are fundamental requirements regarding fire safety and access to sunshine. In other words, side setback areas must be approached in terms of both urban design and urban management. Therefore, based on Lee and Park [

13], focusing on urban residents’ demand for the use of space, this study gathers opinions from experts who regulate and manage the actual space. To this end, we (1) identify the status and illegalities of using side setback areas and (2) conduct a survey and interview with experts, thereby establishing a direction for guidelines for using side setback areas based on their intended purpose.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Survey Results on the Use of Side Spaces

5.1.1. Categorization of Space Use

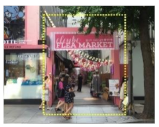

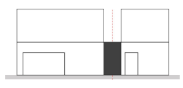

We surveyed 372 side spaces found at the study sites. Approximately 48.7% (Type G) maintained their original function as an outdoor annexed parking lot installed according to the Parking Lot Act. Other spaces were vacant lots formed as an annexed parking lot or remaining vacant lots within the building site that were used for business activities, closed or neglected. To determine the patterns of use, we conducted a complete enumeration and categorized the spatial characteristics according to the standards of the legal system, the functional characteristics according to the current use, and the physical characteristics, such as form and size. Spaces with a frontal width of less than 1 m were excluded as they were perceived as gaps blocked by green space.

The first-level classification was based on physical, functional, and institutional characteristics. The functions were divided into different categories, but then reclassified into the following, considering the business type and form: existing stores, independent stores, parking spaces, vacant lots, closed spaces, and gaps. They were ultimately classified as Types A–G (

Table 6). Other than the sites that maintained the current function as an annexed parking lot, 31.8% of the sites (Types A–E) were engaged in active commercial activities using side spaces (see

Table 7).

Type A is the form that expanded the indoor space of lower-level stores to the side by extending or establishing a temporary building. Type B additionally secured an outdoor space of lower-level stores by installing an outdoor terrace or display stand. These types were mostly occupied and used via the annexed parking lot on the side for business activities without permission. This shows that many stores preferred to secure retail space over using the space as a parking entrance, which increased the continuity of roadside stores.

Type C is the form that installed an accessway and outdoor staircase leading into the store in either the rear lot, from underground, or from at least two stories high. This type is not related to the store on the first floor that is adjacent to the space and secures an accessway; thus, the width of the space bordering the street was 3 m or smaller. In other words, because this type requires a relatively small space, most stores used the remaining vacant lot within the building site. Moreover, they installed plantations, display stands, and terraces on the accessway itself, which appeared to be decorated when seen from the sidewalk.

Type D is the form in which a small independent store was set up in the side spaces separately from the physical building through an extension of the space or by establishing a temporary building. Type E is the form in which temporary business activities (such as a flea market) were carried out separately from the stores in the building by installing an outdoor terrace or display stand. Type D mostly featured independent sales facilities, such as street vendors, using materials that are easy to set up and tear down. Type E changed the annexed parking lot or remaining vacant lot that was usually empty into a temporary commercial space on weekends or at night, constructed with the same type of materials as Type D.

Type F was a case of passive use of space, where the space was too small and, thus, remained closed or was left as an empty lot for the storage of goods. This study focused on Types A–E because our intention was to determine the possibility of system reform for the active use of side spaces.

5.1.2. Violation of Legislations

To determine the conflicts of the current legal system and the use of space more accurately, we analyzed the violations of legislation in the building ledger for roadside buildings in the research sites (see

Table 8). As a result of extracting only violations in side setback areas, 93 (39%) out of 238 buildings in the Sinsa neighborhood were listed as illegal buildings. Of the 309 buildings in Hapjeong, 98 (32%) had records of violations, most of which were categorized as multiple violations. In both sites combined, there were approximately 1.79 cases of violations on average per illegal building.

The specific details of the violations were classified into three types. First, most cases were unauthorized changes in the use of parking spaces. Owing to the nature of the architectural plan within general residential areas, there were many cases in which there was at least one side of an outdoor annexed parking lot that was installed, mostly located on the side of the building. Some stores illegally changed the use of these parking spaces to extend the indoor space of the building or installed a terrace or deck to use as a restaurant, or café, or to sell clothes. They used materials or facilities that were easy to demolish and reinstall, thereby possibly repeating the violation after a crackdown.

Second, business activities were carried out by expanding sales space through unauthorized extensions to the side vacant lot or by installing temporary facilities, such as tables. This was mostly found inside side spaces adjacent to the street, aside from the rear of the building, among vacant lots based on the Building Act (Articles 58, 61, and 49) and Article 242 of the Civil Act. These spaces were used not only for direct business activities but also for functional commercial uses such as storage, a kitchen extension, a maintenance office, and stowage.

Third, there was an unauthorized occupation of space by installing an outdoor staircase to access the store from underground, at least two stories high. The general residential areas in which the sites are located feature many detached or row houses distributed in terms of architectural planning. As the streets are commercialized, semi-basements or spaces from at least two stories high are changed into commercial spaces, starting with the lower levels. There were many cases in which an outdoor staircase was built, occupying the side space, to create an access way from the outside.

To summarize the features of the studied sites, at least 30% of all buildings in the sites violated the law regarding the use of side spaces, and similar violations occurred constantly in the same space. Moreover, the same violations occurred after crackdowns, even when the store owners were aware that they were illegal. This was generally used to secure lower-level retail spaces and access ways. This shows that there is a constant conflict between the demand for the use of these spaces and the legal system.

5.2. Results of the Feasibility Study with Experts

The twenty experts who participated in the survey coincidentally took part in the crackdowns on the sites and had experience of conducting research on legal systems regarding the use of space. The responses for each survey item were as follows.

First, there were opinion items regarding the use of side spaces. The experts responded that business activities in vacant lots outside the building were clearly illegal and, thus, undesirable. However, this was also something to be reviewed positively (as long as there were no safety issues) if legitimate standards are established for operation. Next, they were asked about the commercial use of side spaces, such as the installation of advertisements. They responded that this is also an illegal act, and the law cannot be operated flexibly in this environment. However, the participants conceded that some acceptable utilizations could be allowed to operate, such as a mobile cart or temporary trailer for business by the hour, if it does not present a safety hazard such as a fire hazard or the hindrance of evacuation or if it does not disrupt the streetscape. Some experts argued that there may be encouragement at the administrative level in the guidelines prior to a system reform.

Second, there were questions about crackdowns on the use of side spaces. Most of the experts responded that crackdowns are for unauthorized changes in use, and the intention is to promote public welfare, settle civil complaints, maintain urban aesthetics, and establish law and order. Law enforcement normally visits the scene when there is a complaint, and the crackdown is carried out through the following procedures: corrective order, correction demand, notice on imposing a charge for compelling the execution, and pressing charges on the building owner after 10 days, 20 days, 30 days or more. The penalty is imposed on the building owner; however, law enforcement is not aware of who pays the penalties in the end, which implies insufficient institutional measures regarding the protection of store owners.

The experts also pointed out other difficulties, such as the challenge of cracking down on a violation that involves the entire street rather than an individual structure. In fact, crackdowns can be meaningless in this context because violations continue regardless. Therefore, there is a need for the drastic reform of regulations to apply new laws for when the entire street is changed for commercial use. The experts all agreed that the current system lacks effectiveness and that a new system is needed. Although it is important to comply with related laws, they acknowledged the demand for amending the Building Act that enables the use of space as long as there are no safety issues, such as a hindrance of evacuation.

Third, there were questions about the demand and direction for system reform regarding side spaces. First, they expressed a public perception that the current legislation fails to meet actual demand. The participants expressed an understanding of the current demand of urban residents and the difficulties in meeting these demands; thus, the public sector must consider public interests above those of agents. However, they said there were cases in which some people requested amendments to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport for system reform. Moreover, institutional support under the current legislation seems impossible, and it is necessary to establish a systematic policy plan that may activate the use of side spaces by boldly adopting the cases in advanced countries. The experts emphasized that this demand and improvement must be based on public welfare and safety.

Overall, the experts responded that it is unreasonable to use side spaces while violating current laws and systems. However, they pointed out that the sites changed from a residential area to a more commercialized area, and that the current system is inflexible. Therefore, the current system must be reformed so that it can be used when safety and sanitation requirements are met.

5.3. Setting the Direction for System Reform and Guidelines

This section summarizes the results of examining the use of side spaces, reviewing the relevant laws and systems, and an in-depth survey of the experts based on social discussions. At this point, there is a need for a system reform for the rational use of side spaces; thus, we establish the direction for this reform as follows, based on the key considerations already outlined.

5.3.1. Directions for System Reform

The results of the analysis revealed that Korea still does not have a separate official announcement on management plans or regulations regarding specific actions for business activities on vacant lots within building sites, such as the use of side spaces. Thus, a new urban space management system must be considered to meet the changing demand for space.

First, it is necessary to rationalize the regulations by changing social awareness about the commercial use of side spaces. Other countries have occupation permits for large and small facilities related to commercial use, such as terraces, display stands, souvenir stands, and outdoor billboards (e.g., ODAs in Singapore). This is based on the collective awareness that commercial activities vitalize the region and contribute to improving the city’s appeal. Therefore, using unused space commercially may be one way to achieve harmonious coexistence with the demand for more space.

Second, procedures must be established for district designations to consider and apply the unique characteristics of each place. The commercialization of idle space may contribute to regional vitalization, but it may also raise conflicts with nearby residents, since the district is also a residential area [

13]. Therefore, to permit the commercial use of side spaces, the spatial scope must be limited, and standards must be established, such as the type of facilities or business hours. Thus, it is necessary to improve the general system for the rational use of vacant lots within building sites and to establish district designation requirements and procedures for effective implementation.

Third, equity and procedural legitimacy must exist while applying the system to reach social consensus. Despite the increasing demand for system reform, there are still conflicts between relevant parties, such as complaints raised by nearby residents or controversies regarding public officials. Merchants want to actively use the space to increase their operating income, and users enjoy dining or shopping in a pleasant, open space, whereas nearby residents complain about various problems caused by these business practices. Thus, it is necessary to reach a social consensus by adopting adequate regulation plans.

5.3.2. Setting the Direction for Guidelines

Under the assumption that system reform will be implemented, the specific guidelines for regulations and the use of space can be set as follows. First, there must be specific standards for layout, size, elements, maintenance, and management. Various activities such as sales, promotions, and pedestrian rest spots separate from traffic in commercial streets contribute to street vitalization and landscaping. However, when permitting the commercial use of the lower levels and side spaces of buildings, specific standards must be provided regarding layout, size, elements, maintenance, and management to maintain public safety, private property rights, and a pleasant environment.

Second, public agreement procedures must be established. The process of forming, using, maintaining, and managing commercial roadside or building lower levels and side spaces involves various agents, such as administrative agencies, residents, building owners, store owners, and consumers, with many conflicts of interest. Thus, it is necessary to set a direction for the use and establishment of relevant standards based on public agreement procedures.

Third, the direction of long-term management must be reestablished. Two rules must be followed before establishing a management direction. First, the head of the local government must select streets where a certain number of buildings’ lower levels are commercialized in residential areas. Second, in vacant lots within a building site, activities that disrupt escape routes are prohibited. To permit business inside side spaces for long-term management based on these two rules, it is necessary to establish space utilization plans, assuming that the purpose of the business is to improve pedestrian convenience or street aesthetics and to vitalize the regional economy. For the efficient management and safety of space, rules must be established, such as street conditions for permission, facility location or type or safety standards, space management, and the collection of fees.

5.3.3. The Basic Content of the Guidelines

Based on the above, we designed the following basic content for the guidelines. The guidelines for the use of side spaces provide a reference for establishing facility standards in each autonomous district. Autonomous districts use these guidelines to revise and supplement specific items and criteria depending on the site characteristics and conditions. The main contents of these guidelines include permissions and basic directions for the use of side spaces, categories, and key items to consider in facility standards and minimum facility requirements.

The purpose of the commercial use of side spaces is to contribute to efficient land use and street vitalization using small pieces of land in the city, which are formed within general residential areas and promote urban regeneration and vitality. Furthermore, such activities are permitted as long as they do not violate matters regarding safety or sanitation.

The specific contents of the guidelines are listed in

Table 9. First, they include construction and facility safety standards, suggesting criteria that secure the safety of users directly or indirectly using them according to the Building Act and the Act on Fire Prevention and Installation, Maintenance, and Safety Control of Firefighting Systems. Second, they establish facility standards, which include the type of facilities that can be installed within side spaces, installation principles, and detailed criteria. Third, they provide maintenance standards, or the duties of business managers, such as business hours and cleaning periods, so that the use of side spaces does not hinder the sanitation of street spaces or surrounding living environments.

In addition, it is necessary to implement step-by-step management and operation plans. For example, in the initial step, the current system must be aligned with the district unit plan or environmental improvement project to enable autonomous management underlined by resident agreements (landscape agreements or merchant community projects) and meet the relevant legal requirements. Next, the phased maintenance of the relevant system is included, such as system reform on the formation or limited use of vacant lots limited to areas that are fully commercialized among those with the characteristics of residential areas.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the significance of side setback areas (the open side spaces of buildings) in the dense urban architectural structure of the overpopulated city of Seoul, South Korea. This open space between buildings is a significant physical urban component in minimizing the spread of fire. In actual usage in Seoul, which was the research subject, urban citizens tend to voluntarily use such spaces. Side spaces are small, unused, and often neglected spaces in overdeveloped cities that can be used for various purposes; however, they were originally formed to ensure fire safety and to guarantee access to sunlight. Therefore, even if the utility value of side spaces is proved by this research, it is necessary to consider their original purpose, such as safety and sanitation, as well as how they are actually used. This study conducted in-depth interviews and surveys with 20 experts in charge of managing actual side spaces and studied the related regulations.

The analysis proceeded as follows. First, we undertook a full investigation of 371 spaces and inspection of violations of the building law. As a result of the analysis, violations were classified into seven types; among them, five types (A–E) consisted of active engagement in commercial activities in such spaces. These were violations, in that the business space and the access road had been secured. Second, the feasibility of using the spaces was investigated for the 20 experts, collecting opinions on business activities, facility installation, and gathering opinions on the bases for crackdown, effectiveness, and improvement of the system. Most of the experts pointed out that the current laws and systems should be improved, while safety and sanitary conditions must be implemented. Therefore, it is apparent that the current system must be reformed so that it can be used for the demands of residents if and when all safety and sanitation requirements are met. Based on the above, this study establishes a new direction for system reform and suggests the basic features and guidelines to implement this reform.

Through the results of this study, we established a guideline for utilizing the side setback areas, while accepting basic sanitary conditions such as fire safety guarantees and the right to sunlight. The guidelines are general documents referenced to establish standards for facilities using separate spaces in each autonomous district, and include specific standards for arrangement, scale, element, maintenance, and management. First, the width of the passage (0.9 to 1.5 m) for evacuation and firefighting was set, and the degree of availability of the remaining vacant lot was suggested. Second, for solar access, the size and height of temporary facilities installed in the remaining vacant lot were set to be less than the first floor of the adjacent store. Third, it was established that allowed facilities shall be installed in consideration of publicity and street aesthetics. In addition, only facilities considering publicity and street aesthetics are allowed. Fourth, in order to maintain a pleasant street environment, the available time, period, and cleaning condition of the side setback area were set. Finally, it was established that, in situations such as the expiration of the business license period and the occurrence of civil complaints, the business shall be immediately suspended and the space shall be restored to its original state. If institutional improvement is made based on the guidelines presented in this study, economic, social, and cultural significance can be created in the following areas.

First, small open spaces can be generated and used at a low cost. Using vacant lots for this purpose increases land-use efficiency. This also enhances the efficiency of public management by reducing the social costs of crackdowns on violations. It is also possible to gain added tax revenues and reinvest in other public projects by legalizing the use of side spaces, which ultimately forms a virtuous cycle. Street aesthetics also improve when side spaces are used in this way. The landscape value is increased by creating continuous and diverse commercial streetscapes, while also securing local safety and a pleasant environment by clearly establishing the standards for facilities that can be installed within side spaces.

Second, in the case of Seoul, the study site, there was no consideration for such residual spaces, and the act of simply occupying space itself was judged to be illegal. Therefore, recognizing the existence of the space and creating a system that can manage it, is considered a new approach for Seoul in urban space management. Likewise, it is believed that the effectiveness of related support projects, such as permitting outdoor business, will be strengthened. Seoul’s land use system can be supplemented from a modern perspective via the guidelines in this study.

Third, the results of this study meet not only the fundamental purpose of using side spaces productively in overpopulated urban spaces, but also the general needs of urban residents in the utilization of unused space. Discussions on side spaces presented two conflicting views: one, that they are necessary for fire prevention and, two, that they must be used and not neglected. The significance of this study is that, first of all, it reminds us of the importance of separation spaces. The second is that it proposes a fire prevention function and, at the same time, a practical use of the space between buildings.

This study analyzed Seoul, where many activities were carried out on side spaces. Thus, the guidelines and system reform direction are provided based on legal systems applicable only to the city of Seoul. However, the results of this study can be applied to a variety of cities exhibiting a similar tendency, in order to establish regulations or activation systems for the management of side spaces, after considering their unique characteristics. Furthermore, it is necessary to conduct a feasibility study on the direction provided by experts from diverse fields, thereby laying the groundwork for an actual system reform.