Unpacking B Corps’ Impact on Sustainable Development: An Analysis from Structuration Theory

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- How, and to what extent, does B Corps impact SD?

- RQ2:

- How do B Corps influence social structures to impact SD?

2. Theoretical Background

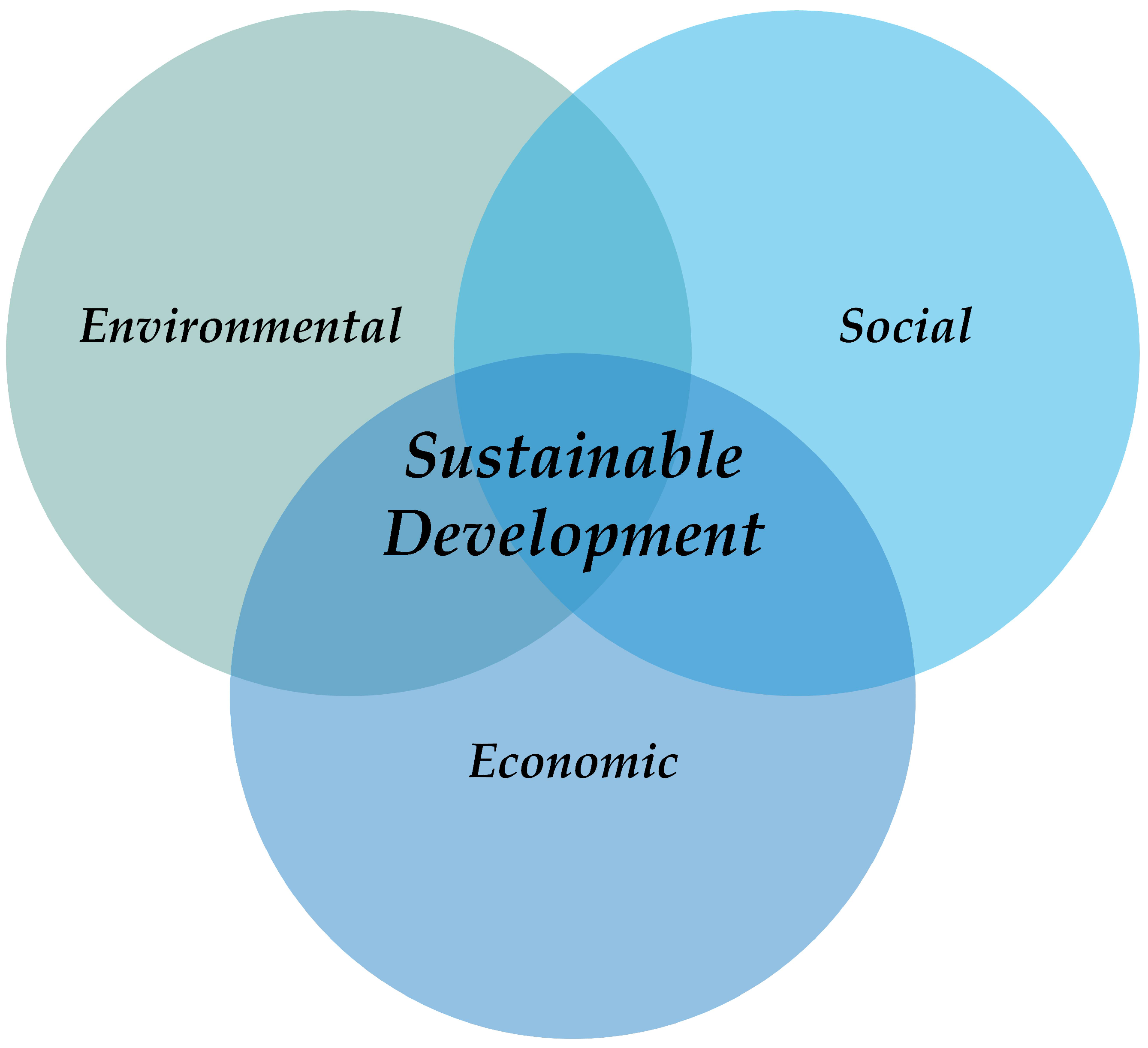

2.1. Sustainable Development and Hybrid Organisations

2.2. B Corp: A Sustainability-Oriented Hybrid Organisation

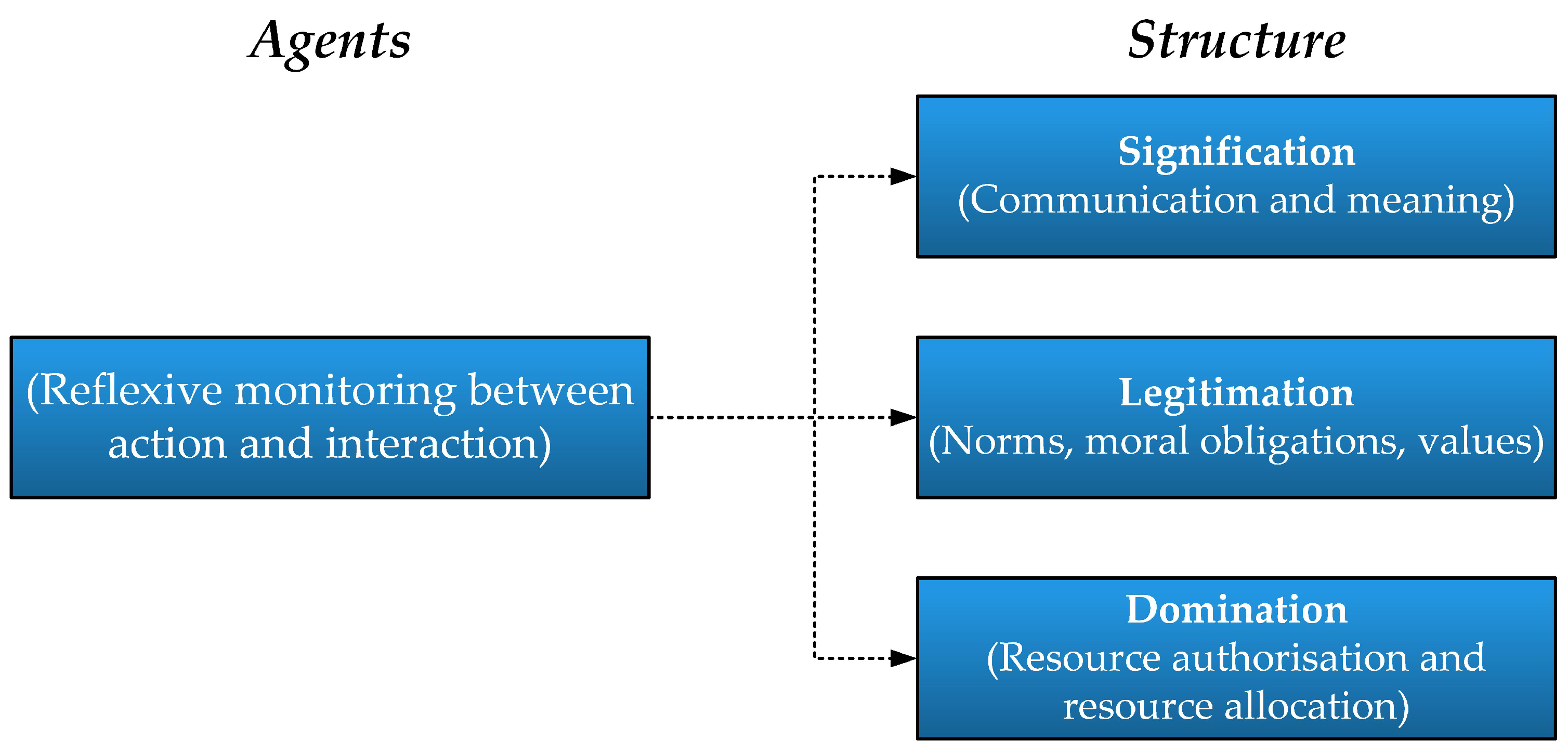

2.3. Structuration Theory

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Setting

3.2. Data Collection

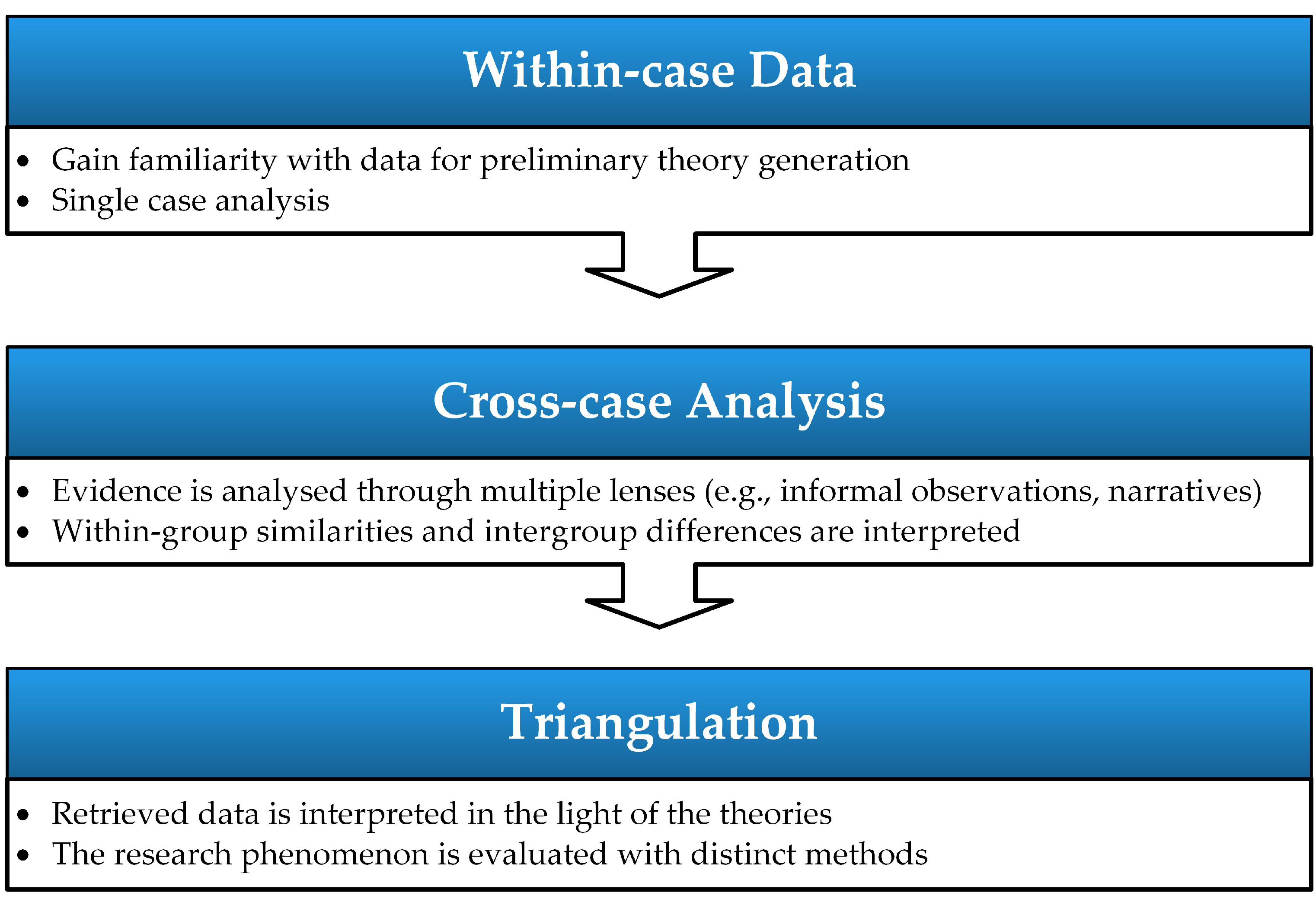

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. B Corps Impact on Sustainable Development

4.1.1. Considering Future Generations

4.1.2. Human Development

4.1.3. Novel Mindsets, Behaviours, and Lifestyles

4.1.4. Socio-Political Engagement

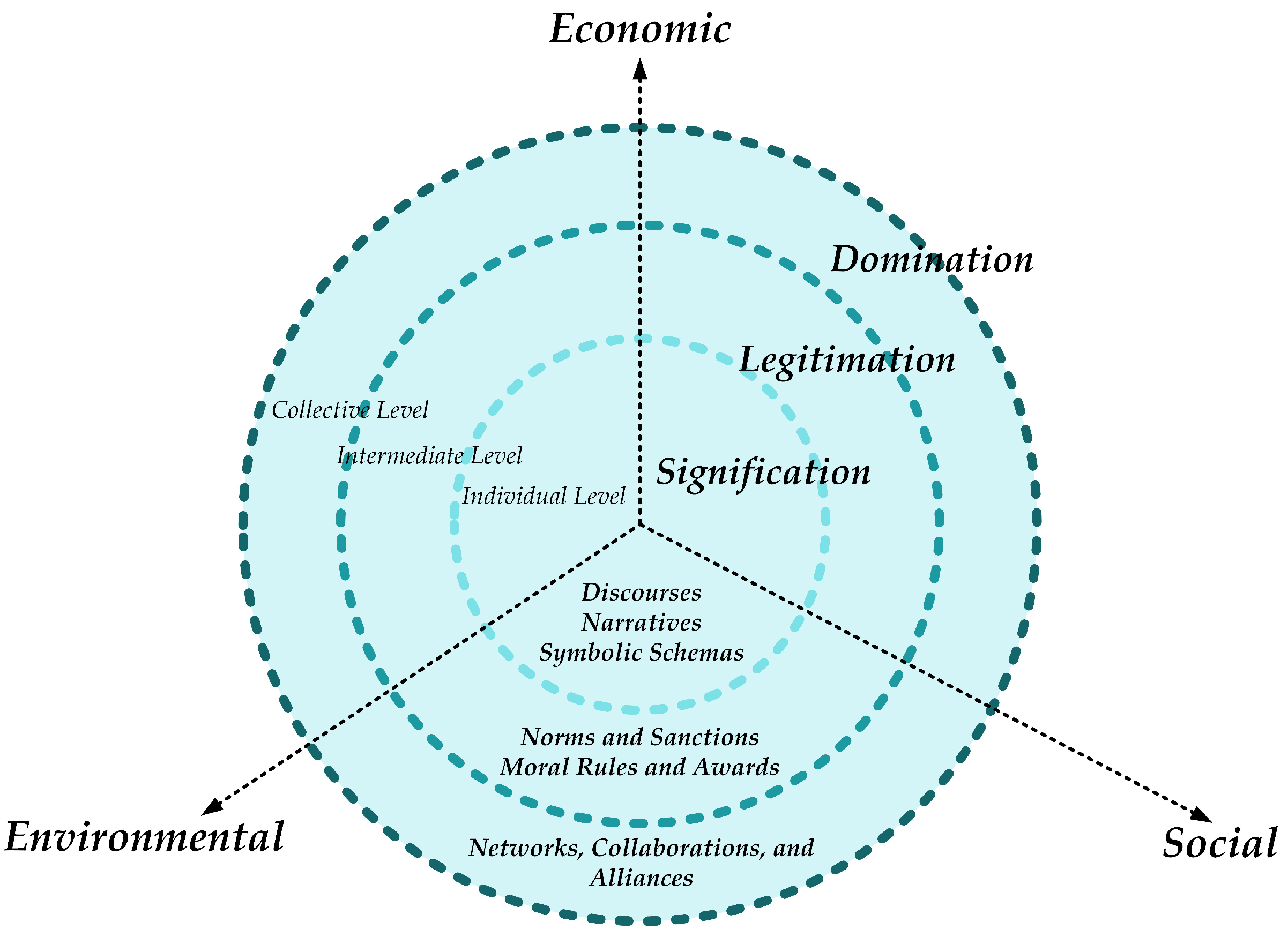

4.2. B Corps Impact in Sustainable Development: An Interpretation from the Structuration Theory Lenses

4.2.1. Signification

We are convinced that the bicycle is an element of change in the structure of our society. Specifically, the bike helps us build a more collaborative economy and brings us closer to each other.(Mejor en Bici)

The private sector is capable of making the whole world work in one way or another, and this capacity to address the problems of inequality, the climate crisis and poverty is an impressive hope.(Informant 1)

Together, we can find the solution to many of the problems that consumerism, industrialisation, and technology have created.(Terramarte)

Our model is a profit through purposes model. We believe in the transformative capacity of private enterprise, which is greater than that of an NGO. We believe in capitalism to transform the world. It is not savage capitalism, nor compassionate capitalism, but a moderate, redistributive, inclusive capitalism.(Cafexport)

The B movement in Colombia seeks to transform the private sector and the traditional version of capitalism, understanding that the traditional version, although it has brought many benefits to humanity, is also responsible for some of the big problems in terms of inequality and in terms of transgressing planetary ecological limits.(Informant 4)

We try to be very consistent with what we propose. We do not use flyers; all information is electronic. We ride a bicycle; we use public transport. We are consistent between what we are and what we promote.(Sentido Verde)

As a company, we are aligned to the SDGs, and we know in advance which SDGs we are targeting when we work with an organisation or a community. We help organisations to align or understand how their product or core business is aligned with the SDGs.(Indeleble Social)

4.2.2. Legitimation

We believe in the power of traditions and ancestral wisdom, mixed with technical knowledge and technology to create businesses that are respectful of communities, and that generate social, environmental and economic well-being.(Ecosistema Jaguar)

We are an organisation that supports the solution of all social and environmental challenges of public, private and non-profit organisations. We have organised six work cells; each one serves very different clients and has very different challenges, but always aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that the world has been working towards since September 2015, at the COP21 in Paris.(Portafolio Verde)

We focus on triple impact; this is really the focus as a B-system. As a global B movement, we encourage companies to differentiate their financial performance as regularly as their social and environmental measures. This is already a global trend, and that is why we believe that the focus should not only be on the business ecosystem but globally as we seek to change the rules of the game of how we are influencing public policy.(Informant 6)

Some things that cannot be judged so lightly. We need to uphold very clear ethical limits. We have anti-corruption policies and we are signatories to the Global Compact. We have a full anti-corruption and transparency paragraph in our statutes. In our Internal Working Rules, we have client exclusion criteria.(Portafolio Verde)

There are companies that want to do the best practices and have the best standards. I call them ‘standard enterprises’. But other companies that like to be full in all standards, they believe in certifications, but regardless of the certification, whatever the standard lovers are, they like to be at the forefront and achieve a B impact.(Informant 5)

4.2.3. Domination

More than 60% of our manufacturers are women, and many of them are vulnerable or disabled. We are working with these populations through a project with the United Nations Development Programme from October 2019 to promote their economic integration into society.(Terramarte)

5. Discussion

5.1. B Corps: At the Intersection of the TBL

5.2. Impacting Sustainable Development: Lessons from the Structuration Theory

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- UNRISD. Policy Innovations for Transformative Change: Implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UNRISD/UN Publications: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alter, K. Social Enterprise: A Typology of the Field Contextualized in Latin America; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hestad, D.; Tàbara, J.D.; Thornton, T.F. The Three Logics of Sustainability-oriented Hybrid Organisations: A Multi-disciplinary Review. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 16, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Rathert, N. Let’s Talk about Problems: Advancing Research on Hybrid Organizing, Social Enterprises, and Institutional Context. In Organizational Hybridity: Perspectives, Processes, Promises; Besharov, M.L., Mitzinneck, B.C., Eds.; Research in the Sociology of Organizations; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020; Volume 69, pp. 189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M.; Biggeri, M.; Testi, E. Social Economy and Social Business Supporting Policies for Sustainable Human Development in a Post-COVID-19 World. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, F.; Etzion, D.; Gehman, J. Tackling Grand Challenges Pragmatically: Robust Action Revisited. Organ. Stud. 2015, 36, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabares, S. Do Hybrid Organizations Contribute to Sustainable Development Goals? Evidence from B Corps in Colombia. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B Lab. About B Lab. Available online: https://bcorporation.net/about-b-lab (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Zebryte, I.; Jorquera, H. Chilean Tourism Sector “B Corporations”: Evidence of Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W. Characterising B Corps as a Sustainable Business Model: An Exploratory Study of B Corps in Australia. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 144, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and B Corps. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B Lab. About B Corps. Available online: https://bcorporation.net/about-b-corps (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Marquis, C. Better Business: How the B Corp Movement Is Remaking Capitalism; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin, J. The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism; Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Abramovay, R.; Correa, M.E.; Gatica, S.; Van Hoof, B. Nuevas Empresas, Nuevas economias: Empresas B en Suramerica. Available online: http://academiab.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/nuevas_empresas__nuevas_economias_las_empresas_b_en_suramerica_2013.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Munck, L.; Tomiotto, M.F.; Santana, A.M.; Borges, M.; Corbett, B.A. To B or not to B: Is the B movement really changing the meaning of business success in Brazilian companies? In Proceedings of the Towards Sustainable Technologies and Innovation Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference of the International Association for Management of Technology, IAMOT, Birmingham, UK, 22–26 April 2018; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Saiz-Álvarez, J.M.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Castillo, D. B Corps: A Socioeconomic Approach for the COVID-19 Post-crisis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society. Outline of the Theory of Structuration; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, A.I.; Dear, M.J. Structuration Theory in Urban Analysis: 1. Theoretical Exegesis. Environ. Plan. A 1986, 18, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabares, S. Certified B Corporations: An Approach to Tensions of Sustainable-driven Hybrid Business Models in an Emerging Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, B.; Hopwood, B.; O’Brien, G. Environment, Economy and Society: Fitting them together into Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, B.; Mellor, M.; O’Brien, G. Sustainable Development: Mapping Different Approaches. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hourneaux Jr, F.; da Silva Gabriel, M.L.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.A. Triple Bottom Line and Sustainable Performance Measurement in Industrial Companies. Rev. Gestão 2018, 25, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanclay, F. The Triple Bottom Line and Impact Assessment: How do TBL, EIA, SIA, SEA and EMS Relate to each Other? J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2004, 6, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M. Advancing Research on Hybrid Organizing—Insights from the Study of Social Enterprises. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 397–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.-C.; Santos, F. Inside the Hybrid Organization: Selective Coupling as a Response to Competing Institutional Logics. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M.; Walker, J.; Dorsey, C. In Search of the Hybrid Ideal. Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. 2012, 10, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, F.; Pache, A.-C.C.; Birkholz, C. Making Hybrids Work: Aligning Business Models and Organizational Design for Social Enterprises. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2015, 57, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Utting, P. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals through Social and Solidarity Economy: Incremental versus Transformative Change; UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nigri, G.; Del Baldo, M.; Agulini, A. Governance and Accountability Models in Italian Certified Benefit Corporations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2368–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B Lab. About B Lab. Available online: https://www.binterdependent.org/#About (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Carvalho, B.; Wiek, A.; Ness, B. Can B Corp Certification anchor Sustainability in SMEs? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liute, A.; De Giacomo, M.R. The Environmental Performance of UK-based B Corp Companies: An Analysis Based on the Triple Bottom Line Approach. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “Sustainability Business Model”. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sewell, W.H.J. A Theory of Structure: Duality, Agency, and Transformation. Am. J. Sociol. 1992, 98, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintosh, N.B.; Scapens, R.W. Structuration Theory in Management Accounting. Account. Organ. Soc. 1990, 15, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. New Rules of Sociological Method; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Buhr, N. A structuration view on the initiation of environmental reports. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2002, 13, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R. The Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (SKAD). Hum. Stud. 2011, 34, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubreuil, B.; Grégoire, J.F. Are moral norms distinct from social norms? A critical assessment of Jon Elster and Cristina Bicchieri. Theory Decis. 2013, 75, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Martí, I. Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Source of Explanation, Prediction, and Delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinerowski, A.A.; Steinerowska-Streb, I. Can Social Enterprise Contribute to Creating Sustainable Rural Communities? Using the Lens of Structuration Theory to Analyse the Emergence of Rural Social Enterprise. Local Econ. 2012, 27, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, S. Ethnic Minority Groups and Social Enterprise: A Case Study of the East London Olympic Boroughs; Middlesex University Research Repository: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, K.; Wilson, J.; Tonner, A.; Shaw, E. How can Social Enterprises Impact Health and Well-being? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarason, Y.; Yuthas, K.; Aziz, A. Toward Improving Impact of Sustainable Ventures in Developing Countries: A Structuration View. Bus. Strateg. Dev. 2020, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications. Design and Methods (Applied Social Research Methods), 5th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Analysis. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Better Stories and Better Constructs: The Case for Rigor and Comparative Logic. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 16, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.A. The Misery in Colombia. Desarro. Soc. 2016, 76, 9–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Colombia. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/colombia/oecd-economic-surveys-colombia-25222961.htm (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. The Sustainable Development Goals and COVID-19. Sustainable Development Report 2020; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Paelman, V.; Van Cauwenberge, P.; Vander Bauwhede, H. Effect of B Corp Certification on Short-Term Growth: European Evidence. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbert, M.; Ruigrok, W.; Wicki, B. What Passes as a Rigorous Case Study? Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B. Examining the Validity Structure of Qualitative Research. Education 1997, 118, 282–292. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.; Cole, R.J. Theoretical Underpinnings of Regenerative Sustainability. Build. Res. Inf. 2015, 43, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Cohen, B. Towards a Social-ecological Understanding of Sustainable Venturing. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Bodin, Ö.; Folke, C. Building Transformative Capacity for Ecosystem Stewardship in Social–Ecological System. In Adaptive Capacity and Environmental Governance; Armitage, D., Plummer, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 263–285. [Google Scholar]

- Ziervogel, G.; Cowen, A.; Ziniades, J. Moving from Adaptive to Transformative Capacity: Building Foundations for Inclusive, Thriving, and Regenerative Urban Settlements. Sustainability 2016, 8, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-level Perspective and a Case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K.; Banister, D.; Schwanitz, V.J.; Wierling, A. The Imperatives of Sustainable Development: Needs, Justice, Limits; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, N.; Hoffman, A.J. Hybrid Organizations: The Next Chapter of Sustainable Business. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 41, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, C.; Brandon, P. An Ecological Worldview as Basis for a Regenerative Sustainability Paradigm for the Built Environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haigh, N.; Hoffman, A.J. The New Heretics: Hybrid Organizations and the Challenges They Present to Corporate Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Capability Expansion. In Readings in Human Development; Fukuda-Parr, S., Shiva Kumar, A., UNDP, HDRP, Eds.; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Beyond the Social Contract: Capabilities and Global Justice. Oxford Dev. Stud. 2004, 32, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K.; Banister, D. The Imperatives of Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability Transitions: An Emerging Field of Research and its Prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, G.M.; Schwarz, E.J. What Sustainable Development Goals do Social Innovations Address? A Systematic Review and Content Analysis of Social Innovation Literature. Sustainability 2019, 11, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piccarozzi, M. Does Social Innovation Contribute to Sustainability? The Case of Italian Innovative Start-Ups. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, A.; Stocker, L. What is a Transition? Exploring Visual and Textual Definitions among Sustainability Transition Networks. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 50, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlmann, F.; Stubbs, W. The Role of Purpose in Supporting Sustainability Transitions. Acad. Manag. 2021, 2021, 12847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| B Corp | Business Description | Interviewees |

|---|---|---|

| Indeleble Social | Experiential training and corporate volunteering | Executive Director/Co-founder, General Manager/Co-founder, Project Coordinator, Administrative Coordinator |

| Mejor en Bici | Bicycle sharing service | General Manager/Co-founder |

| Terramarte | Reusable Ecological Bags | General Manager, Director of Marketing and Communications |

| Jaguar | Agri-food Services Consultancy | CEO/Founder |

| Sentido Verde | Environmental Consultancy and Education | General Manager/Co-founder, Commercial Director |

| Alcagüete | Healthy Snacks | Managing Director/Co-Founder, Marketing Coordinator |

| Siembra Viva | Organic Farm and E-commerce Market Place | CEO, Director of Operations, four Farmers |

| Cafexport | Coffee and Cacao | CEO, General Manager, Director of Sustainability (two interviews) |

| B Corp | Examples * |

|---|---|

| Indeleble Social |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Mejor en Bici |

|

| |

| Terramarte |

|

| |

| Ecosistema Jaguar |

|

| |

| Sentido Verde |

|

| Alcagüete |

|

| Siembra Viva |

|

| Cafexport |

|

| Portafolio Verde |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tabares, S.; Morales, A.; Calvo, S.; Molina Moreno, V. Unpacking B Corps’ Impact on Sustainable Development: An Analysis from Structuration Theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313408

Tabares S, Morales A, Calvo S, Molina Moreno V. Unpacking B Corps’ Impact on Sustainable Development: An Analysis from Structuration Theory. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313408

Chicago/Turabian StyleTabares, Sabrina, Andrés Morales, Sara Calvo, and Valentín Molina Moreno. 2021. "Unpacking B Corps’ Impact on Sustainable Development: An Analysis from Structuration Theory" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313408

APA StyleTabares, S., Morales, A., Calvo, S., & Molina Moreno, V. (2021). Unpacking B Corps’ Impact on Sustainable Development: An Analysis from Structuration Theory. Sustainability, 13(23), 13408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313408