Abstract

The intention-action gap stands out in research on sustainable consumption for decades. The current research explores the role of socially desirable responding (SDR) in the appearance of this gap by utilising an indirect questioning technique. Two online experiments ( and ) demonstrate, in line with most market surveys, that consumers present themselves as highly responsible when being assessed with the standard survey measurement approach (i.e., direct questioning). However, the responses of participants toward the exact same measures of consumers’ social responsibility perceptions and behavioural intentions heavily drop when applying an indirect questioning technique, indicating a substantial overstatement of consumers’ social responsibility perceptions in traditional market surveys. Furthermore, this study provides novel evidence regarding the validity and underlying mechanism of the indirect questioning technique, thereby alleviating long-lasting concerns about this method. Implications for the intention–action gap discussion and consumer ethics research are proposed.

1. Introduction

One of the most pervasive notions in research on sustainable consumption and consumer social responsibility is the so-called attitude–action or intention–action gap [1,2]. The large inconsistency between what consumers say and how they actually behave in the marketplace is considered one of the most puzzling challenges for both academics and practitioners aiming to understand and motivate sustainable consumption [3,4].

Interestingly, most inferences for the presence of this gap derive from contrasting information of two separate sources, i.e., consumer self-reports and market shares [5,6,7]. On the one hand, within self-reports a majority of consumers persistently expresses strong support and high intentions to consider social-ecological aspects within private consumption e.g., [8,9]. On the other hand, market agencies reveal ongoing low market shares of products that actively endorse high social-ecological standards (e.g., organic or fair trade products) and relatively insusceptible market shares of products from companies that violate commonly held social-ecological values (e.g., through usage of sweat shop labour and resource squandering) [10].

In addition to other factors, such as the wilful ignorance of ethical attributes [11] or moral disengagement mechanisms [12,13], there is also initial evidence that large parts of this discrepancy might be merely due to inaccuracies of traditional survey measures, since they are prone to socially desirable responding (SDR) [14]. Consequently, marketing-based attempts aiming to encourage sustainable consumption might rely on systematic misperceptions about real states of consumers’ pro-sustainable attitudes and intentions, potentially leading to employment of strategies that are ultimately ineffective and squander scarce resources.

However, despite the profound implications of potential SDR-tendencies in traditional survey measures generating artificial notions of an intention–action gap in sustainable consumption contexts, to this day, academic literature lacks straightforward evidence on this issue. Furthermore, while there is a wide range of methods to generally address SDR in survey-based research (e.g., SDR-Tendency Scales, Randomized Response Techniques, and Bogus Pipeline Approaches), most of these methods are associated with severe shortcomings (e.g., validity concerns, high effort/costs, and ethical concerns) [15] and are, therefore, of limited utility to cope with SDR-issues in traditional market surveys. Thus, we build upon a particular technique for preventing socially desirable response tendencies that turned out to be both effective and easy to employ, i.e., indirect questioning [16,17]. This technique utilises humans’ propensity to respond more truthfully when being able to project owned psychological states that are potentially undesirable on another entity (e.g., on a referent group) [18]. Yet, to the knowledge of the authors, within research on consumer social responsibility and sustainable consumption, the potential of this technique has not been explored systematically so far.

Therefore, the current research’s main objective is twofold. First, we aim to investigate the ability of indirect questioning to elicit more realistic responses in the domain of consumer social responsibility (e.g., feelings of moral obligation or behavioural intentions towards unsustainable products), thereby assessing the seriousness of SDR effects in such contexts. Second, we aim to provide novel evidence for the validity of this questioning technique related to an inherent and long lasting concern. That is, do respondents indeed implicitly reveal their own feelings, beliefs, and intentions when being approached by indirect questioning or do they just predict those of the respective referent group, rendering results invalid [19]? Thus, our research contributes to the literature on consumer social responsibility by showcasing the relevance of SDR tendencies in surveys on sustainability-related attitudes and intentions, as well as by improving our understanding regarding the ability of the indirect questioning technique to provide SDR-free measures more generally.

2. Theoretical Background and Predictions

2.1. Indirect Questioning Technique and Socially Desirable Responding

Socially desirable responding refers to response tendencies that occur primarily in self-assessment procedures, such as those typically used in personality or attitude measurements [20,21]. In such cases, the respondents do not give an answer that really applies to them, but answer in a way that is socially desirable from their point of view [16]. A major reason for this is to leave a positive impression by giving answers that conform to expectations and to receive social recognition or at least to avoid social rejection [22]. This impression management is often motivated by maintaining or actually increasing self-esteem and is to be distinguished from self-deception, in which a person assumes that the evaluation actually applies to him or her [23]. Furthermore, socially desirable responding is seen to emerge either as a more general personality trait, which can be further distinguished upon fundamental value orientations and the level of its consciousness [24], or from context dependent judgements about the perceived desirability a respondent attributes to a specific item [25,26]. Ethical issues such as the consideration of social-ecological aspects within consumption decisions are generally perceived as being socially desirable traits [14] and respective traditional self-report measures are therefore likely to be affected by item desirability and a general need for approval [27].

The indirect questioning technique is supposed to deprive participants from the motivation to respond in a socially desirable fashion by embarking on the human tendency to project own psychological states onto other entities [18,28]. Psychoanalytic theorists discuss projection as a self-serving defense mechanism, which enables humans to outsource owned “shortcomings” in order to avoid psychological threat [29]. The concept of projection was already applied by Sigmund Freud in various contexts, for example, to explain different psychological phenomena, such as mental illnesses, e.g., paranoia [30] and neuroses [31], as well as to explicate human coping with fear [32] and jealousy [30] or to comprehend the meaning of dreams [33]. Freud understood projection as a simple primitive process of the externalisation of internal mental states and emotions in order to obtain a picture of the outside world [31]. The concept of projection manifests through an attribution of internal drives, properties, and thoughts to an external object [34]. Thus, when projection processes occur, there is a partial transfer of self-presentation to a presentation of objects [35], whereby the objects can also be other people [36]. In this case, people attribute certain characteristics and behaviours to other individuals, which they cannot or do not want in themselves. It is this mechanism that is utilised by the concept of indirect questioning and it has gained great importance not only in psychoanalysis. Indirect questioning techniques have been used for a long time in clinical psychology, motive research, and market research.

In recent decades, various measurement approaches for the indirect determination of needs, attitudes, and values have been developed in order to identify hidden motivations and uncensored attitudes in consumers, which are withheld by the test persons in direct questioning due to feelings of shame or embarrassment [37]. These methods include, e.g., Thematic Apperception Tests (TAT), sentence completion tests, picture storytelling tests, and cartoon tests e.g., [38,39,40,41]. However, all these unstructured measurement methods are qualitative-oriented and often require elaborating materials applicable to the respective survey, e.g., drawing appropriate cartoons or selecting and designing adequate images [42]. In addition, analysing the obtained responses is time-consuming and may introduce distortions due to subjective interpretations of the answers [42]. Accordingly, the reliability and validity of unstructured projective surveys are deemed as problematic [43]. To this end, employing structured approaches with closed questions seems to be helpful since they permit less room for interpretation and for a better comparability of the answers [44].

The indirect questioning technique that is utilised in the current study is one such structured approach. In particular, it enables respondents to project potentially undesirable psychological states (e.g., low levels of caring for ethical issues within a private consumption decision) by a mere alteration of the point of reference for responding to an item. Instead of instructing participants to respond on behalf of themselves (e.g., “How much do you agree with the following statements?”), which is the common standard in traditional survey methods, they are instructed to respond on behalf of an abstract referent group (e.g., “How much would a typical consumer agree with the following statements?”). This is supposed to provide respondents with a feeling of impersonality, allowing for more “realistic” answers even if perceived as socially undesirable [16].

Therefore, we suggest that participants who are approached with indirect questioning to measure consumer social responsibility (e.g., feelings of moral obligation to refrain from consumption options with poor social-ecological value) will omit SDR-related biases within their responses reducing those to lower (i.e., more realistic) levels of consumer responsibility expressions. However, we suggest responses elicited with direct questioning will introduce such biases and therefore indicate higher levels of consumer responsibility expressions. In particular, we expect when consumers judge their perceived social responsibility in regard to consumption options that are of poor social-ecological value, responses on behalf of the self (i.e., direct questioning) will indicate high levels of consumer responsibility perceptions (i.e., problem awareness, self-ascribed accountability, feelings of moral obligation, and pro-sustainable intentions) that are in line with results generally witnessed by traditional surveys. However, we expect for the exact same constructs, when measured with indirect questioning, judgements will indicate much lower levels of social responsibility perceptions, which are more in line with the low real world market shares of ethical products. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Judgements of social responsibility perceptions regarding consumption options with poor social-ecological value will be lower when elicited with indirect questioning than when elicited with direct questioning.

Furthermore, since we expect that the hypothesised differences between social responsibility perceptions in both questioning types are driven by SDR-tendencies, we expect measures that are not prone to social desirability tensions (e.g., functional benefits of products with poor social-ecological value) to be unaffected by the type of questioning. This approach of introducing constructs that are expected to be rather unsusceptible to SDR as baseline measures has been utilised in former studies on SDR with indirect questioning [16]. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Judgements of functional benefits regarding consumption options with poor social-ecological value will be at same levels when elicited with indirect (vs. direct) questioning.

2.2. Response Mode in Indirect Questioning: Prediction or Projection?

In regard to the second objective of this research—evaluating the validity of the indirect questioning technique in more detail—we have developed and applied a tailor-made approach for this purpose. Since participants are asked to indicate responses on behalf of a referent group, a common validity concern is that they might generate mere predictions about the responses of specific referent group representatives [19]. To provide distinct evidence for reconciling this ongoing concern with regard to the indirect questioning technique, we embark on a theory-driven test that utilises individual subjective norms as a yardstick. Since subjective norms are expectations of individuals about what the immediate personal environment judges to be right or wrong [45], norm activation theory and the theory of reasoned action predict them to be particularly related to feelings of moral obligation and behavioural intentions [46,47]. However, the propositions for a relationship of subjective norms with feelings of moral obligation, and with behavioural intentions, respectively, predicate on the premise that relating constructs pertain to the same individual. It is not proposed by those theories that one’s own immediate environment affects moral feelings and behavioural intentions of an abstract other entity. We utilise this logic to clarify the prediction vs. projection issue.

Specifically, we expect when measuring the constructs subjective norms, feelings of moral obligation, and behavioural intentions on behalf of the respondent (i.e., direct questioning), the proposed systematic relationships between subjective norms and both other constructs should be evidenced since the relating constructs explicitly pertain to the same individual. However, maintaining subjective norms being measured on behalf of the respondent (i.e., direct questioning), while feelings of moral obligation and behavioural intentions are measured on behalf of a referent group (i.e., indirect questioning), a systematic relationship between those constructs would not be expected if respondents simply predict the responses of the referent group, since they would not pertain to the same individual as the subjective norms anymore. However, if participants actually project their own feelings of moral obligation and behavioural intentions onto the referent group, we would expect the relationships to remain at the same levels as when all three constructs are measured with direct questioning, indicating projection as the underlying response mode to indirect questioning. We hypothesise the latter and propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).

Judgements of feelings of moral obligation and behavioural intentions to forego products with poor social-ecological value, measured with direct questioning (i.e., on behalf of the self), are positively correlated with the subjective norms of one’s own social environment for considering social-ecological aspects within consumption decisions.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).

Judgements of feelings of moral obligation and behavioural intentions to forego products with poor social-ecological value, measured with indirect questioning (i.e., on behalf of a referent group), are positively correlated with the subjective norms of one’s own social environment for considering social-ecological aspects within consumption decisions.

3. Study 1

The primary objective of study 1 is to provide initial evidence for the occurrence and seriousness of SDR-tendencies in regard to consumer social responsibility judgements toward a product with poor social-ecological value, thereby assessing H1 and H2. This study also aims to provide evidence for the projection vs. prediction issue based on our theory-driven approach with subjective norms as a yardstick (H3a and H3b). We investigate consumer social responsibility judgements and behavioural intentions in this study toward a durable product that is associated with an above average carbon footprint within production.

3.1. Procedure and Participants

This study was part of an online experiment that was conducted at a large university in Germany. A total of 306 participants ( female) were recruited in exchange for a EUR 5 compensation from a local subject pool. During an initial registration process, participants already responded to a measure of green consumption values by Haws et al. [48] alongside other general beliefs and personality traits. To prevent priming effects from responding to the GREEN scale, only after 48 h (not known to the participants) the invitation link for the main study was sent by email.

Participants clicked on the link in the invitation email and started the study. After reading a short introduction, they were presented with an Amazon-like product display that contained a fictional rating attesting a high carbon footprint during production (see Appendix A), aiming to manipulate respondents’ perceptions of the product as being unsustainable (for a similar approach, see [17,48]). Participants were asked to inspect the display and then to judge different product qualities (e.g., price, delivery time, and sustainability). The averaged sum score of the sustainability measure (“environmentally harmful” vs. “environmentally friendly”, “climate-damaging” vs. “climate-friendly”, and “ecologically short-sighted” vs. “ecologically sustainable” (Cronbach’s ), measured on 7-point scales, indicated that our sustainability manipulation was successful and participants perceived the product as of poor social-ecological value (t-test vs. scale midpoint of four; ). After this, participants were provided with different information regarding the production mode of the product (before or after order), which is not part of the present reporting.

Then participants were asked to judge various statements pertaining to problem awareness, self-ascribed accountability, feelings of moral obligation, and behavioural intentions in regard to the displayed product. For this, we randomly assigned participants to one of the two questioning conditions (i.e., direct questioning condition and indirect questioning condition). In the direct questioning condition, participants were asked to judge these items on behalf of themselves (“How much do you agree with the following statements?”). In the indirect questioning condition, participants were instructed to judge the items on behalf of a “typical German consumer” (“How much do you think a ‘typical German consumer’ would agree with the following statements?”). Corresponding to the respective questioning condition, participants were also asked to judge the functional benefits of the product and the importance they attribute to each benefit either on behalf of themselves or on behalf of a “typical German consumer”. The wording of all items was identical across both groups.

After this, participants responded to a measure of perceived subjective norms regarding friends and family to consider social-ecological aspects within consumption decisions, all on behalf of themselves. Lastly, they responded to manipulation checks and to demographic measures.

3.2. Measurements of Focal Constructs

The constructs included in our study that tapped consumers’ social responsibility (i.e., problem awareness, self-ascribed accountability, feelings of moral obligation, and corresponding behavioural intentions) originated from typical theoretical conceptualisations for explaining prosocial behaviour, such as the norm activation model [46] and its descendant the value belief norm theory [49]. For operationalisation, we identified relevant measurements from the literature and tied the context to the issue entailed in the experimental setting (i.e., purchasing a product with a high carbon footprint in production; see Appendix B). As a note to the following description of the measurements, for scales with two items, we additionally used the Spearman-Brown coefficient next to Cronbach’s to evaluate reliability, as it represents a robust measure when the correlation of the two items is relatively strong [50]. Furthermore, Cronbach’s /Spearman-Brown of the indirect questioning condition is presented in square brackets.

As measurement for problem awareness, we employed the awareness of need scale from Harland et al. [51] with two items (Cronbach’s [], Spearman-Brown []) using a 7-point response format ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). Self-ascribed accountability was measured with the situational responsibility scale from Harland et al. [51] consisting of two items (Cronbach’s [], Spearman-Brown []) with a 7-point response format ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). To capture feelings of moral obligation, we formed a scale with a whole of five items (Cronbach’s []) with three self generated items and two items adapted from Vining and Ebreo [52] all measured with a 7-point response format ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). As measurement for purchase intention, we included an instrument from Perugini and Bagozzi [53] with two items (Cronbach’s [], Spearman-Brown []) and for word-of-mouth intention an instrument from Lindenmeier et al. [54] with three items (Cronbach’s []), all measured with a 7-point response format ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree).

Furthermore, drawing on Fisher [16], for functional benefits, participants were asked to judge how much they [a typical German consumer would] belief that the product is “stable” and “comfortable” (ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely), Cronbach’s [=0.80], Spearman-Brown []) and how they [a typical German consumer would] evaluate the importance of these characteristics (ranging from 1 (very unimportant) to 7 (very important), Cronbach’s [=0.83], Spearman-Brown []). Lastly, the measurement for subjective norms, that was only retrieved with direct questioning, was adapted from Taylor and Todd [55] and consisted of two items (Cronbach’s , Spearman-Brown ) measured with a 7-point response format ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). All measures were averaged to mean sum scores for the analysis.

3.3. Findings

3.3.1. Effects of Questioning Type on Consumers’ Stated Social Responsibility and Functional Benefit Evaluations

First, we ensured no systematic differences in the levels of green consumption values and ratings of social-ecological product value p = 0.47) between the two question type conditions, which could have otherwise confounded the results.

Next, we assessed the impact of questioning type on reported social responsibility perceptions and behavioural intentions regarding the product with poor social-ecological value. We conducted a series of five ANOVAs with questioning type as the independent factor and the respective dependent constructs problem awareness, self-ascribed accountability, and feelings of moral obligation as measures of social responsibility perceptions, as well as purchase intention and word-of-mouth intention as measures of behavioural intentions. As expected, the means in the direct questioning condition substantially exceeded those from the indirect questioning condition for all three constructs measuring social responsibility perceptions , , as well as for the reported purchase intentions and word-of-mouth intentions where the type of questioning had an even more pronounced effect (see Table 1). This means respondents expressed significantly lower levels of social responsibility perceptions and significantly higher intentions to purchase and recommend the product with poor social-ecological value when being approached with indirect questioning. The evaluation of the corresponding effect sizes applying recommendations of Cohen [56], yielded large effects of question type on all social responsibility perceptions and behavioural intentions, except for feelings of moral obligation for which a medium effect was evidenced. Most interestingly, comparing the means of purchase intention in the direct questioning condition with the indirect questioning condition , we find them to be located on opposite scale sides, both significantly different from the mid point 4 in the respective direction (, ; , ). This means when participants were being asked directly, they responded on average that it is rather “unlikely” to purchase the product with poor social-ecological value. However, when being asked indirectly (i.e., on behalf of a “typical German consumer”) the average response was that it would be rather “likely” to purchase the product with poor social-ecological value (see Table 1). This indicates the mean responses did not just differ in relative terms, but actually changed scale sides between both types of questioning.

Table 1.

Impact of Questioning Type on Responses to Consumers’ Stated Social Responsibility and Benchmark Constructs.

Next, we focus on the effects of questioning type on the social desirability insensitive constructs. We conducted three ANOVAs with questioning type as the independent variable and the measures of functional benefit beliefs, functional benefit evaluations, and the functional benefit beliefs × functional benefit evaluations interaction [16] as dependent variables, respectively. As expected, for all of our benchmark constructs, no effect of questioning type on mean responses emerged (see Table 1), which supports that SDR is driving the differences between the direct and indirect questioning type. Therefore, these results support hypothesis 1 and 2. Next, we focus on whether participants indeed projected their own thoughts and feelings onto the referent group (i.e., “typical German consumer”), or just predicted those of potentially imagined representatives.

3.3.2. Results on Prediction vs. Projection as Response Mode to Indirect Questioning

First, we calculated the Bravais-Pearson correlation coefficients for both of the relationships, i.e., subjective norms (SN) with feelings of moral obligation (MO) and with purchase intention (PI), respectively, within the direct questioning condition. As expected, the coefficient was significantly different from zero for both of the relationships (, ; , ), supporting hypothesis 3a. Next, we calculated the correlation coefficients for the relationships of subjective norms with feelings of moral obligation and with purchase intention, respectively, for the indirect questioning condition, i.e., where feelings of moral obligation and purchase intention were measured with indirect questioning. The resulting correlations were also significantly different from zero for both relationships (, ; , ) and exhibited the same directions as in the direct questioning condition. Further, a Fisher’s z transformation was conducted to test for significant differences between the correlations, revealing neither a significant difference for the correlations of feelings of moral obligation and subjective norms , nor for the correlations between purchase intention and subjective norm . That means the predicted relationships derived from norm activation theory and theory of reasoned action were also apparent when feelings of moral obligation and behavioural intentions were measured with indirect questioning, while subjective norms were measured with direct questioning. Therefore, hypothesis 3b is confirmed, and based on our argumentation, the notion of projection as the underlying response mode for participants in the indirect questioning condition is supported. We also examined whether the correlations in the indirect questioning condition of subjective norms with feelings of moral obligation and with purchase intentions, respectively, differed across different levels of green consumption values, since one might suspect a matching effect between moderate levels of green values and a definition of a “typical German consumer”, participants may have had in mind in the indirect questioning condition as an alternative explanation for these results. However, no systematic effects of green consumption values on the relationships of subjective norms with feelings of moral obligation , and with purchase intentions , respectively, were apparent.

4. Study 2

After having established initial support for the notion of serious SDR-effects in traditional survey measures for consumers’ stated social responsibility in study 1, the overall objective of study 2 was twofold. First, we aimed to replicate the findings of study 1 in another context under investigation. Thus, in this study we chose a different product category (i.e., clothing) and shifted the sustainability issue from environmental to social (i.e., bad working conditions). Second, we aimed to substantiate our findings regarding the validity of the indirect questioning technique derived from study 1 by replicating the findings of our theory-based validation approach (H3a and H3b). Additionally, we benchmarked the indirect questioning technique against a digital variant of the so-called item randomised response technique (IRRT), another technique for mitigating SDR tendencies ex ante within self-reports [57]. In its original form, this technique, by design, renders the researcher blind to the true responses of each survey participant. This is realised by having participants to throw a dice before responding to every item, which determines whether a truthful or a forced answer is to be given. Consequently, the researcher is then only able to analyse the responses on an aggregate level, applying laws of probability to determine shares of true responses for each scale point, without the possibility to judge an individual answer to be true or forced. When communicated properly to participants, this technique is able to reduce SDR-tendencies effectively by providing a feeling of real privacy allowing for true responses even when considered socially undesirable [57].

Thus, in accordance with the first study, we expect responses to consumer social responsibility constructs [behavioural intention] elicited with the traditional direct questioning approach again will exceed [fall below] those elicited by the indirect questioning technique. However, since we hypothesise only SDR-effects to be reflected in the observed differences between direct and indirect questioning, we expect indirect questioning and IRRT-responses to be at same levels. Along that same line of thought, for constructs supposedly free from SDR-tensions (i.e., judgements of functional benefits), we expect responses in all three questioning conditions to be at same levels.

4.1. Participants and Procedure

A total of 334 participants was recruited from the German clickworker platform “consumerfieldwork.de” to take part in the online experiment. Thirteen participants had to be excluded due to failing the attention checks or indicating “no” as response to the seriousness or comprehension checks. Thus, the responses of 321 participants ( = 25.8; 48.3% female; 1.2% diverse, 3.1% no gender indication) remained for analyses.

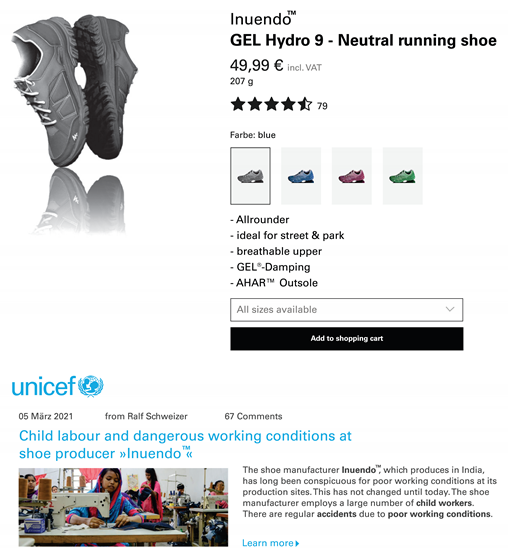

After following the invitation link to the welcome page, participants firstly indicated their gender and age. Then, they were randomly assigned to one of the three questioning technique conditions, i.e., direct questioning, indirect questioning, or IRRT. They were then presented with a product presentation of a running shoe from the fictitious brand “Inuendo” and read a complementary online mock article of “unicef”, illustrating bad working conditions and cases of child labour at the production facilities of “Inuendo” (see Appendix C). In the IRRT-condition, participants received further background information about the anonymisation logic of the IRRT and instructions about its precise procedure prior to the product presentation. They also completed two trials regarding statements that were independent from the issues investigated in the main part of this study (e.g., driving behaviour). After having inspected the product page and having read the complementary article, participants in all three experimental conditions judged the same set of statements regarding problem awareness, self-ascribed accountability, feelings of moral obligations, behavioural intentions, and functional beliefs regarding the presented product. The instructions within the direct and indirect questioning conditions followed the ones that were used in study 1. While in the direct questioning condition participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement on behalf of themselves (“How much do you agree with the following statement?”), participants in the indirect questioning condition were instructed to judge the statement on behalf of a typical consumer (“How much do you belief a typical consumer would agree to the following statement?”). In the IRRT-condition participants were instructed to click on a digital dice, placed above each statement, prior to every response. When the dice showed a number from 1 to 4, they were to indicate their “truthful answer”. When they threw a 5 or 6, they were to role the dice again by clicking the animation and to provide the corresponding answer of the dice. In order to also ensure forced answers for scale-point 7, participants were instructed when they threw a 6 to indicate 6 when the previous throw was a 5 and indicate 7 when the previous throw was a 6. After participants responded to the measures of consumer social responsibility, behavioural intentions, and functional benefits, we measured subjective norms regarding the consideration of working conditions as a general buying criteria in all three conditions with the direct questioning technique as in study 1. Lastly, participants responded to some data quality measures, were debriefed, and directed to the provider for receiving payment.

4.2. Measurements

Within this study, we utilised only single item measurement models, since the procedure of the item randomised response technique is rather time consuming on each item and identical measurements were to be used across all experimental conditions. The consumers’ social responsibility constructs were all measured with a 7-point response format ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). The corresponding items are depicted in the Appendix D. For functional benefit perceptions, participants were asked to judge the likelihood that the presented product was expected to be “comfortable” and “durable” on a 7-point response format ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely). Furthermore, they were asked to evaluate the personal importance of these functional criteria within a running shoe on a 7-point response format ranging from 1 (very unimportant) to 7 (very important). The measurement model for subjective norms was identical to study 1, however, we adjusted the focal sustainability issue to “working conditions”.

4.3. Findings

To investigate the influence of the questioning technique (direct vs. indirect vs. IRRT) on consumer social responsibility judgements and functional belief perceptions, we conducted a series of nine ANOVAs entailing the type of questioning as the independent variable. For consumer social responsibility judgements, we included problem awareness, self-ascribed accountability, feelings of moral obligation, purchase intention, and word-of-mouth intention as the respective dependent variables. For functional benefit perceptions, the two functional benefit beliefs “comfortability” (A) and “durability” (B), as well as the two corresponding importance evaluations were included as the respective dependent variables into the ANOVAs. For all subsequent pairwise comparisons, we employed a Bonferroni-correction of the p-values, since it represents a conservative and stringent form of alpha-error correction [58].

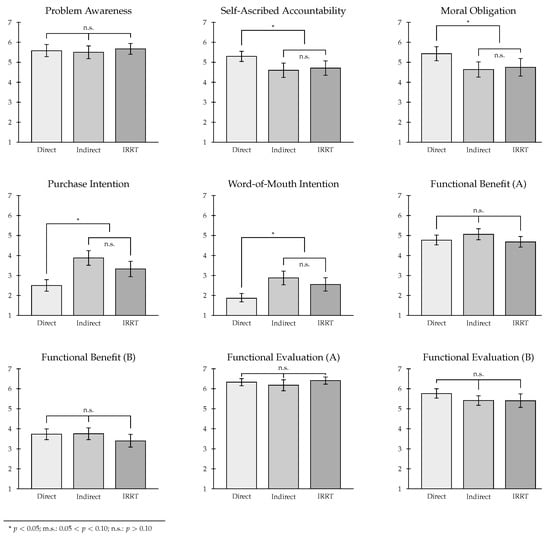

The ANOVAs revealed systematic group differences between the means for most of the consumer social responsibility constructs and behavioural intentions; i.e., self-ascribed accountability (), feelings of moral obligation ( ), purchase intention (), and word-of-mouth intention (), with the exception of problem awareness where no systematic mean differences were apparent (). Pairwise group comparisons on the constructs of consumer social responsibility perceptions [behavioural intentions] further revealed that the means of the direct questioning condition indeed significantly exceeded [fell below] those from the indirect questioning and IRRT condition. However, the means of the indirect questioning and IRRT condition did not differ significantly for consumer social responsibility judgements and behavioural intentions (see Figure 1 and Appendix E). Furthermore, for functional benefit perceptions, no systematic differences were found for any of the four measures, i.e., for the functional benefit beliefs A () and B (), as well as for the two corresponding importance evaluations A () and B (), replicating the findings of study 1 regarding H1 and H2 also in light of the IRRT as a second benchmark. Overall, these results additionally support the notion that SDR-tendencies drive the observed differences between direct and indirect questioning for the social responsibility constructs and behavioural intentions. In the case of problem awareness, we suspect that because of the vivid illustration of the utilised sustainability issue (i.e., bad working conditions) within the experimental stimulus, participants might have perceived this particular problem as especially salient, so that potential differences due to SDR-tendencies were offset. At the same time, however, it shows that while social desirability had no influence on problem perceptions for this particular issue, it still influenced perceptions of one’s own accountability perceptions and moral attitude towards the problematic issue at hand.

Figure 1.

Means of consumer social responsibility constructs, behavioural intentions, and functional benefit beliefs (Study 2).

Next, in order to further substantiate the results of the previous study regarding the question of prediction vs. projection as the underlying response mode of indirect questioning, we repeated the correlation analyses for feelings of moral obligation and purchase intentions with subjective norms, this time, for all three questioning conditions. In line with our hypotheses (H3a and H3b), for the relationship of feelings of moral obligation with subjective norms, we found no differences of the Bravais-Pearson correlation coefficients between the direct questioning and indirect questioning condition (), between the indirect and IRRT condition () as well as between the direct and IRRT condition (). The same pattern emerged for the correlations between purchase intentions and subjective norms. No differences between the Bravais-Pearson correlation coefficients of the direct questioning and indirect questioning condition (), as well as between the indirect and IRRT condition (), and between the direct and IRRT condition () emerged. Thus, based on our argumentation, these results further support the notion of projection as the underlying response mode of the indirect questioning technique.

5. Discussion

The current research provides distinct evidence for severe SDR-biases within self-reports on consumer social responsibility perceptions and intentions measured with a traditional survey format (i.e., direct questioning). It further showcases the ability of the indirect questioning technique to mitigate such SDR-tendencies ex ante. Particularly, within two studies, participants tended to report strong endorsements of social responsibility beliefs and attitudes regarding products with poor social-ecological value, and fairly low purchase and word-of-mouth intentions towards them when being asked with the traditional direct questioning technique. However, responses towards the exact same measures of social responsibility beliefs and attitudes dropped and stated purchase as well as word-of-mouth intentions increased, when utilising an indirect questioning technique. At the same time, no differences between both questioning types emerged for social desirability insensitive constructs across both studies (i.e., functional benefit beliefs and evaluations), indicating SDR-tendencies are driving the observed differences. Furthermore, utilising a second technique to mitigate SDR-tendencies ex ante as an additional benchmark (i.e., IRRT), further supported this notion. In our second study, responses towards consumer social responsibility measures [behavioural intentions] elicited with direct questioning, exceeded [fell below] responses in both the indirect questioning- and the IRRT-condition for all but one construct. However, responses within indirect questioning condition and IRRT-condition were mostly aligned for these SDR-sensitive constructs, further indicating SDR-tendencies to be captured in these observed differences. Thus, our findings suggest, when responding to a direct questioning format, participants are tempted to present themselves in an overly positive light by exaggerating their concerns and moral feelings regarding the social-ecological issues of products (e.g., high carbon footprint) and by downplaying their respective behavioural intentions towards it. The obtained results are also in line with previous research comparing the effect of direct vs. indirect questioning on self-reports in other domains [16,44,59].

Furthermore, the current research provides novel evidence regarding the validity of the indirect questioning technique as a means to circumvent SDR-tendencies within survey-based research, particularly regarding the long lasting validity concern of whether participants indeed reveal their own psychological states and not just predict those of the utilised referent group. The theory-driven approach we applied in this research, utilising subjective norms as a yardstick, supports the notion that participants actually do project their own psychological states, as opposed to just predicting those of the respective referent group. Specifically, we showed that the relationships of directly measured subjective norms with indirectly measured feelings of moral obligation as well as with indirectly measured purchase intentions exhibited similar correlations as when all constructs were measured with direct questioning. Additionally, these relationships did not differ from those observed within the IRRT-condition in study 2. Thus, these results indicate projection to be the underlying response mode for indirect questioning, which substantiates the validity of the indirect questioning technique as means to acquire SDR-free belief and attitude statements in survey-based research more generally.

6. Implications

6.1. Academic Implications

The findings of this research have important implications in a variety of ways. First, they contribute to the question of why we actually perceive a gap between attitudes and intentions of consumers stated in market polls and actual levels of sustainable consumption in the marketplace. Our results suggest this gap might largely be driven by an overly positive picture consumers tend to paint about their pro-sustainable attitudes and intentions in traditional surveys, which might not reflect their true psychological states that are brought to the marketplace. Second, our studies add to the validity concern regarding indirect questioning as a means to circumvent socially desirable responding. To that end, this research converges existing validation attempts [44] to the domain of consumer social responsibility research. More importantly, it provides novel evidence that participants actually project themselves onto the referent groups and not just predict referent group responses, which is a long lasting concern in regard to indirect questioning [15,16,17]. Our results also demonstrate that a structured form of questioning can be a valid approach for projective investigations of attitudes, which is easier to design and to evaluate than unstructured questioning techniques. Thus, this research equips researchers with an increased certainty of the validity of this simple and yet easy to employ technique to elicit more truthful survey responses from participants in regard to issues that are at risk of social desirability tension such as attitudes and intentions towards (un-)sustainable consumption.

6.2. Managerial Implications

Furthermore, our research entails important implications for practitioners as well. First, practitioners aiming to gather insights into consumers’ sustainability related attitudes receive guidance on both determining the relevance of SDR within market poll responses when utilising a traditional opinion measurement approach (i.e., direct questioning) and a potent pathway for effectively circumventing such SDR tendencies. To that end, this research showcased an effective adjustment of the traditional survey measure and further highlights the preservation of its validity. It thereby guides also political institutions, dealing with ecological sustainability, to possibilities for more correct assessments of consumers’ mindsets.

Second, while it is often generally assumed that a large majority of consumers is equipped with positive attitudes and good intentions to consume sustainably, the current findings point to the fact that this might not reflect reality as such. Thus, raising positive attitudes and intentions regarding sustainable consumption still seem to be highly crucial target constructs which should be addressed within marketing activities that aim to encourage sustainable consumption. Consequently, basic attitude-oriented campaigns, e.g., informational campaigns that address raising problem awareness of unsustainable consumption or responsibilities as consumers for sustainability, still seem highly relevant instruments for the practice of motivating sustainable consumption.

7. Limitations

However, there are limitations that should be mentioned. First, our studies were conducted for two specific products with two particular social-ecological issues (i.e., carbon product footprint and bad working conditions) assessed under laboratory conditions, which might provide results differing from real market fields and from other “product by issue” combinations. It also needs to be mentioned that the studies focused on products that were associated with explicit negative properties and observed effects might differ for products with explicit positive effects. Second, we relied on convenience samples containing younger and more educated participants than the general public, which might concur with a particular sensitivity for sustainability-related issues. Lastly, no cultural influences were taken into account that might increase or decrease the social desirability bias. For example, in individualistic cultures the bias could be smaller because social desirability is less considered in subjects’ responses than in collectivistic cultures [60].

8. Conclusions and Further Research

Nonetheless, the current research provides straightforward evidence for the seriousness of socially desirable responding within research on consumers’ social responsibility and sustainable consumption. It points out that at least some portion of the perceived attitude or intention–action gap in this domain is artificially induced by socially desirable responding within traditional market surveys using direct questioning techniques. Thus, the attitude–behaviour gap seems to appear partly due to a false measurement of attitudes and behavioural intentions rather than individuals being unable to implement desired sustainable behaviours due to (insufficient) self-regulatory processes (including old habits and insufficient stamina) or external factors (e.g., lack of opportunities, lack of purchasing power, and time pressure). Our results indicate that the indirect questioning technique is an effective approach to mitigate social desirability biases and can thus contribute to a more valid assessment of the attitude–behaviour relationship in regard to sustainable consumption. This research further suggests a novel account for assessing the validity of the indirect questioning technique based on subjective norms as a theory-based benchmark construct. We hope this might stimulate further research into the generalisability of our findings regarding the validity of the indirect questioning technique more general. For instance, what role might perceived social distance of the utilised referent group play for the response mode (projection vs. prediction) in regard to indirect questioning? What aspects of socially desirable responding (self-deception vs. impression management) are actually captured by indirect questioning? How do participants respond who know about the logic of the indirect questioning technique? What are potential problems when using indirect questioning in cross-cultural studies? Thus, it is our belief that future research on socially desirable responding and employing indirect questioning as a means to circumvent it, will facilitate our understanding of the intention–action gap and institute a refined discussion on motivating sustainable marketplace behaviours.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and A.M.; methodology, S.K.; software, S.K.; validation, S.K. and A.M.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, S.K.; resources, A.M.; data curation, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K. and A.M.; visualization, S.K.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, S.K. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies were conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the studies.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in these studies are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Stimulus Material Study 1

|

Appendix B. Constructs and Items Study 1

| Problem Awareness * [51] |

|

| Perceived Self-Accountability for CO2 Impact * [51] |

|

| Feelings of Moral Obligation * [52] |

|

| Purchase Intention * [53] |

|

| Word-of-Mouth Intention * [54] |

|

| Subjective Norm * [55] |

|

| Social-ecological Product Value *** |

|

| All items were measured with 7-point Scales, * anchored from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree), ** Self-generated Items, *** 1 = left extreme / 7 = right extreme. All scales were translated into German using a backward forward translation approach. |

Appendix C. Stimulus Materials Study 2

|

Appendix D. Constructs and Items Study 2

| Construct | Item |

| Consumers’ Stated Social Responsibility | |

| Problem Awareness | Buying products that are produced under poor working conditions prevents possible improvements in the social situation of the workers. |

| Self-Ascribed Accountability | If I decide to buy this product, I am personally responsible for the social injustices associated with its production. |

| Feelings of Moral Obligation | I would have a guilty conscience if I bought this product. |

| Purchase Intention | I would buy the product offered. |

| Word-of-Mouth Intention | I would recommend friends or acquaintances to buy the product offered. |

| Benchmark Constructs | |

| Functional Benefit (A) | The running shoe offered is comfortable. |

| Functional Benefit (B) | The running shoe offered is durable. |

| Functional Evaluation (A) | How important is it to you in principle that a running shoe is comfortable? |

| Functional Evaluation (B) | How important is it to you in principle that a running shoe is durable? |

| 1 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), 2 7-point scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely), 3 7-point scale from 1 (very unimportant) to 7 (very important). | |

Appendix E. Pairwise Comparisons Study 2

| Condition | n | Mean | SD | p-Value of Pairwise Comparison | ||

| Indirect | IRRT | |||||

| Problem Awareness | Direct | 84 | 5.58 | 1.42 | 0.217 | 0.208 |

| Indirect | 80 | 5.50 | 1.43 | 0.211 | ||

| IRRT | 94 | 5.67 | 1.32 | |||

| Self-Ascribed Accountability | Direct | 84 | 5.30 | 1.17 | 0.011 | 0.035 |

| Indirect | 80 | 4.60 | 1.60 | 1.000 | ||

| IRRT | 90 | 4.71 | 1.72 | |||

| Feelings of Moral Obligation | Direct | 84 | 5.43 | 1.60 | 0.012 | 0.043 |

| Indirect | 80 | 4.64 | 1.70 | 1.000 | ||

| IRRT | 75 | 4.75 | 1.92 | |||

| Purchase Intention | Direct | 84 | 2.50 | 1.36 | < 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Indirect | 80 | 3.88 | 1.64 | 0.090 | ||

| IRRT | 98 | 3.33 | 1.92 | |||

| Word-of-Mouth Intention | Direct | 84 | 1.86 | 1.12 | < 0.001 | 0.005 |

| Indirect | 80 | 2.88 | 1.55 | 0.441 | ||

| IRRT | 96 | 2.55 | 1.65 | |||

| Functional Benefit (A) | Direct | 84 | 4.77 | 1.14 | 0.406 | 1.000 |

| Indirect | 80 | 5.06 | 1.25 | 0.139 | ||

| IRRT | 92 | 4.68 | 1.30 | |||

| Functional Benefit (B) | Direct | 84 | 3.73 | 1.22 | 1.000 | 0.349 |

| Indirect | 80 | 3.75 | 1.30 | 0.287 | ||

| IRRT | 84 | 3.40 | 1.44 | |||

| Functional Evaluation (A) | Direct | 84 | 6.33 | 0.83 | 0.902 | 1.000 |

| Indirect | 80 | 6.18 | 1.22 | 0.363 | ||

| IRRT | 85 | 6.41 | 0.85 | |||

| Functional Evaluation (B) | Direct | 84 | 5.76 | 1.08 | 0.240 | 0.198 |

| Indirect | 80 | 5.41 | 1.09 | 1.000 | ||

| IRRT | 87 | 5.40 | 1.57 | |||

| * with Bonferroni-correction. | ||||||

References

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Shaw, D. Who Says There is an Intention–Behaviour Gap? Assessing the Empirical Evidence of an Intention-Behaviour Gap in Ethical Consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, P.; Maklan, S. How Categorisation Shapes the Attitude–Behaviour Gap in Responsible Consumption. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 57, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Miller, R.A. Consumer Responsibility for Sustainable Consumption. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Consumption; Reisch, L., Thøgersen, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 254–267. [Google Scholar]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable Consumption: Green Consumer Behaviour When Purchasing Products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R.; Carrington, M.J.; Chatzidakis, A. “Beyond the Attitude-Behaviour Gap: Novel Perspectives in Consumer Ethics”: Introduction to the Thematic Symposium. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossmann, E.; Gomez-Suarez, M. Words-Deeds Gap for the Purchase of Fairtrade Products: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone Communications. Cone Communications CSR Study 2017; Cone Communications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boccia, F.; Sarnacchiaro, P. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Consumer Preference: A Structural Equation Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, A.; Dobscha, S.; Freund, J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Luchs, M.G.; Ozanne, L.K.; Thøgersen, J. Sustainable Consumption: Opportunities for Consumer Research and Public Policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, K.R.; Irwin, J.R. Willful Ignorance in the Request for Product Attribute Information. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paharia, N.; Vohs, K.D.; Deshpandé, R. Sweatshop Labor is Wrong Unless the Shoes Are Cute: Cognition Can Both Help and Hurt Moral Motivated Reasoning. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 121, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, S.; Mann, A. When the Damage is Done: Effects of Moral Disengagement on Sustainable Consumption. J. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 20, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T.M. Do What Consumers Say Matter? The Misalignment of Preferences with Unconstrained Ethical Intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.B.E.M.; de Jong, M.G.; Baumgartner, H. Socially Desirable Response Tendencies in Survey Research. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisher, R.J. Social Desirability Bias and the Validity of Indirect Questioning. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The Sustainability Liability: Potential Negative Effects of Ethicality on Product Preference. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holmes, D.S. Dimensions of Projection. Psychol. Bull. 1968, 69, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancarrow, C.; Brace, I.; Wright, L.T. “Tell me Lies, Tell me Sweet Little Lies”: Dealing with Socially Desirable Responses in Market Research. Mark. Rev. 2001, 2, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.S.; Chang, L. A Meta-Analytic Multitrait Multirater Separation of Substance and Style in Social Desirability Scales. J. Personal. 2016, 84, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludeke, S.G.; Weisberg, Y.J.; Deyoung, C.G. Idiographically Desirable Responding: Individual Differences in Perceived Trait Desirability Predict Overclaiming. Eur. J. Personal. 2013, 27, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.; Sargeant, A. Dealing with Social Desirability Bias: An Application to Charitable Giving. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paulhus, D.L. Two-Component Models of Socially Desirable Responding. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D.L. Socially Desirable Responding: The Evolution of a Construct. In The Role of Constructs in Psychological and Educational Measurement; Brown, H.I., Jackson, D.N., Wiley, D.E., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2002; pp. 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, A.L. The Relationship Between the Judged Desirability of a Trait and the Probability That the Trait Will Be Endorsed. J. Appl. Psychol. 1953, 37, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gove, W.R.; Geerken, M.R. Response Bias in Surveys of Mental Health: An Empirical Investigation. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 82, 1289–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D.M.; Fernandes, M.F. The Social Desirability Response Bias in Ethics Research. J. Bus. Ethics 1991, 10, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.M.; McLean, J.L. Anthropomorphizing Dogs: Projecting One’s Own Personality and Consequences for Supporting Animal Rights. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, G.G. Self-Serving Biases in Person Perception: A Reexamination of Projection as a Mechanism of Defense. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 90, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. Certain Neurotic Mechanisms in Jealousy, Paranoia, and Homosexuality. In Collected Papers; Strachey, J., Ed.; The International Psycho-Analytical Library; Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1971; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, S. Totem and Taboo: Resemblances Between the Psychic Lives of Savages and Neurotics; Georg Routledge & Sons: London, UK, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, S. Obsessions and Phobias. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud; Strachey, J., Ed.; Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, S. The Interpretation of Dreams. Standard Edition of the Works of Sigmund Freud, 5th ed.; Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1953; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, P. Externalizing/Projection; Internalizing/Identification: An Examination. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2020, 37, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, W.W. A Note on Projective Identification. J. Am. Psychoanal. Assoc. 1980, 28, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, J.; Perlow, M. Internalization and Externalization. In Projection, Identification, Projective Identification; Sandler, J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, C. Projective Techniques in Market Research: Valueless Subjectivity or Insightful Reality? A Look at the Evidence for the Usefulness, Reliability and Validity of Projective Techniques in Market Research. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 47, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judacewski, P.; Los, P.R.; Lima, L.S.; Alberti, A.; Zielinski, A.A.F.; Nogueira, A. Perceptions of Brazilian Consumers Regarding White Mould Surface–Ripened Cheese Using Free Word Association. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2019, 72, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.d.P.F.; Silva, H.L.A.; Kuriya, S.P.; Maçaira, P.M.; Cyrino Oliveira, F.L.; Cruz, A.G.; Esmerino, E.A.; Freitas, M.Q. Understanding Perceptions and Beliefs About Different Types of Fermented Milks Through the Application of Projective Techniques: A Case Study Using Haire’s Shopping List and Free Word Association. J. Sens. Stud. 2018, 33, e12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, A.; Pulido, A.F.; Mesias, F.J. The Role of Packaging and Presentation Format in Consumers’ Preferences for Food: An Application of Projective Techniques. J. Sens. Stud. 2015, 30, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, V.M.; Minim, V.P.R.; Ferreira, M.A.M.; de Paula Souza, P.H.; Da Silva Moraes, L.E.; Minim, L.A. Study of the Perception of Consumers in Relation to Different Ice Cream Concepts. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 36, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catterall, M.; Ibbotson, P. Using Projective Techniques in Education Research. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2000, 26, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, S. Projective Techniques in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Sci. 2000, 28, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.J.; Tellis, G.J. Removing Social Desirability Bias With Indirect Questioning: Is the Cure Worse Than the Disease? In NA—Advances in Consumer Research Volume 25; Alba, J.W., Hutchinson, J.W., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1998; pp. 563–567. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Deshaies, P.; Cuerrier, J.P.; Pelletier, L.G.; Mongeau, C. Ajzen and Fishbein’s Theory of Reasoned Action as Applied to Moral Behavior: A Confirmatory Analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the World Through GREEN-Tinted Glasses: Green Consumption Values and Responses to Environmentally Friendly Products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Eisinga, R.; Te Grotenhuis, M.; Pelzer, B. The Reliability of a Two-Item Scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. Situational and Personality Factors as Direct or Personal Norm Mediated Predictors of Pro-Environmental Behavior: Questions Derived From Norm-Activation Theory. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, J.; Ebreo, A. Predicting Recycling Behavior From Global and Specific Environmental Attitudes and Changes in Recycling Opportunities. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1580–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The Role of Desires and Anticipated Emotions in Goal–Directed Behaviours: Broadening and Deepening the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmeier, J.; Schleer, C.; Pricl, D. Consumer Outrage: Emotional Reactions to Unethical Corporate Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Decomposition and Crossover Effects in the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Study of Consumer Adoption Intentions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, M.G.; Pieters, R.; Fox, J.P. Reducing Social Desirability Bias through Item Randomized Response: An Application to Measure Underreported Desires. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Mathur, M.B. Some Desirable Properties of the Bonferroni Correction: Is the Bonferroni Correction Really so Bad? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeley, S.M.; Cronley, M.L. When Research Participants Don’t Tell It Like It Is: Pinpointing the Effects of Social Desirability Bias Using Self vs. In direct-Questioning. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research Volume 31; Kahn, B.E., Luce, M.F., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Valdosta, GA, USA, 2004; pp. 432–433. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, S. National Culture and Social Desirability Bias in Measuring Public Service Motivation. Adm. Soc. 2016, 48, 444–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).