Transportation Infrastructure Construction and High-Quality Development of Enterprises: Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of High-Speed Railway Opening in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Institutional Background

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3.1. HSR and High-Quality Development of Enterprises

3.2. The Mediating Role of Information Disclosure Quality

4. Methodology

4.1. Data and Sample

4.2. Variables

4.2.1. High-Quality Development of Enterprises

4.2.2. Information Disclosure Quality

4.3. Research Methods

4.3.1. Baseline Model

4.3.2. The Mediating Role of Information Disclosure Quality

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Summary Statistics

5.2. Baseline Results

5.2.1. HSR and TFP

5.2.2. The Mediating Role of Information Disclosure Quality

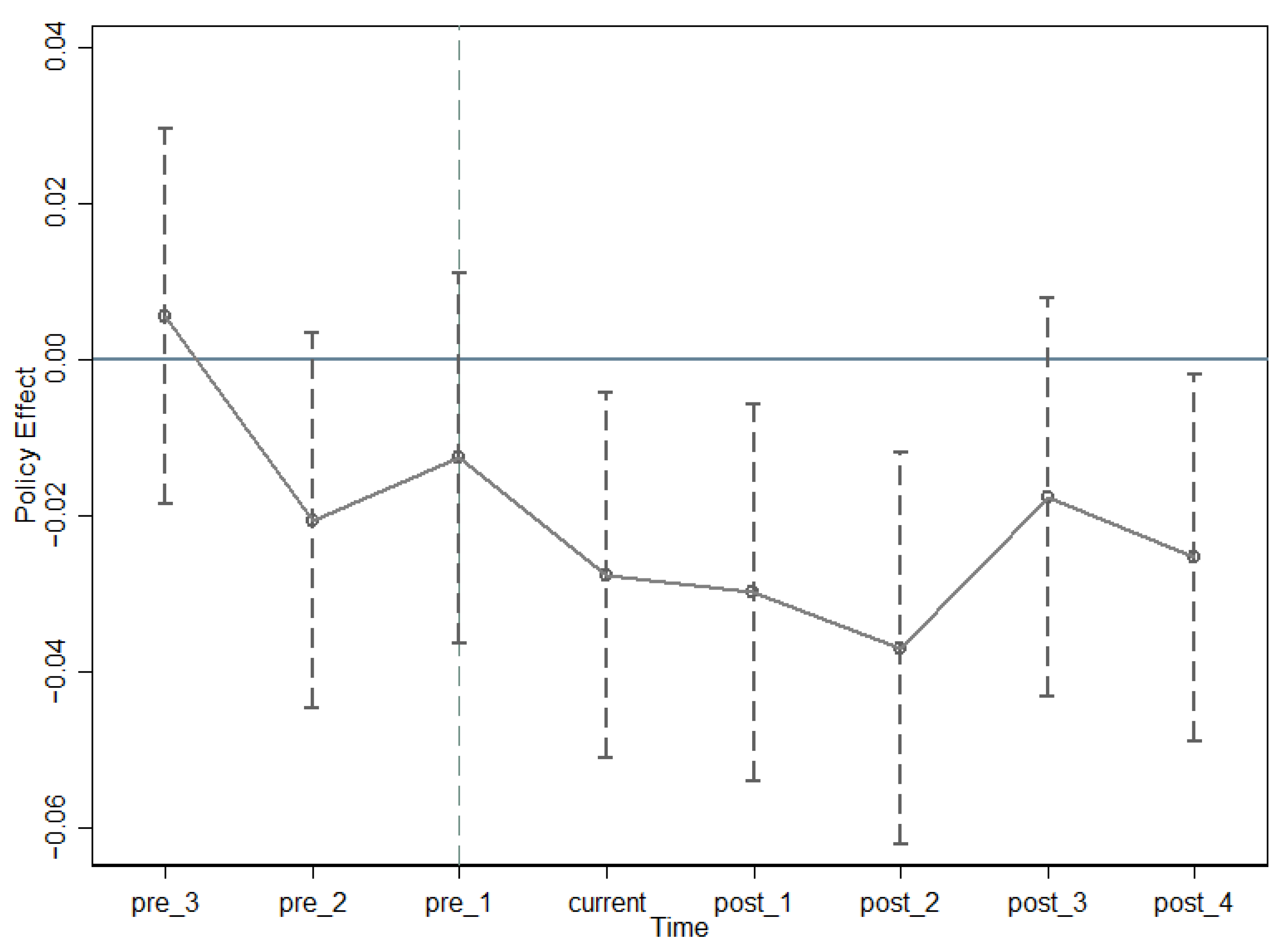

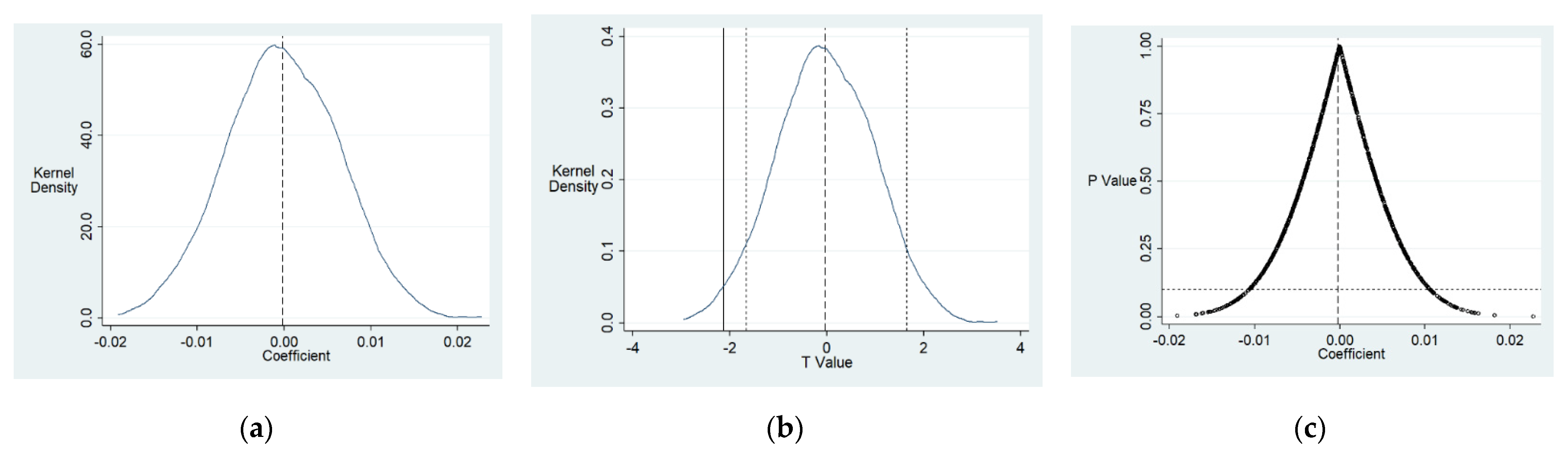

5.3. Endogeneity Mitigation and Robustness Checks

5.3.1. Alternative Measurement for High-Quality Development

5.3.2. Endogeneity Mitigation

5.4. Additional Tests

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Symbols | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | TFP | The total factor productivity of enterprises calculated through Levinsohn–Petrin (LP) method |

| Independent Variables | HSR | If the city where the enterprise is located has high-speed rail in that year, HSR equals to 1, otherwise equals to 0 |

| Intermediary Variable | EM_Accrual | Accrual earnings management calculated through Modified Jones Model |

| EM_Real | Real activity earnings management calculated through Roychowdhury (2006)’s method | |

| Control Variables | SIZE | The natural logarithm of total assets |

| LEV | Total debt/Total assets | |

| ROE | Net income/Total equity | |

| GROWTH | The growth rate of total asset | |

| BtoM | Total assets/Market value | |

| Cashflow | The cashflow of the enterprise | |

| STATE | State-owned firms, STATE = 1; otherwise STATE = 0 | |

| DUAL | The difference between control right and ownership right of a listed company owned by the actual controller | |

| Top1 | The shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder | |

| GDPgrt | The growth rate of annual GDP for each province |

References

- Zou, W.; Chen, L.; Xiong, J. High-speed railway, market access and economic growth. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 76, 1282–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Qian, N. On the Road: Access to Transportation Infrastructure and Economic Growth in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2020, 145, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ke, X.; Chen, H.; Hong, Y.; Hsiao, C. Do China’s high-speed-rail projects promote local economy?—New evidence from a panel data approach. China Econ. Rev. 2017, 44, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. Travel costs and urban specialization patterns: Evidence from China’s high speed railway system. J. Urban Econ. 2017, 98, 98–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, F.; Bruzzone, F.; Nocera, S. Spatial and social equity implications for High-Speed Railway lines in Northern Italy. Transport Res. A-Pol. 2020, 135, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Haynes, K.E. Impact of high-speed rail on regional economic disparity in China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 65, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Sultana, S. The impacts of high-speed rail extensions on accessibility and spatial equity changes in South Korea from 2004 to 2018. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 45, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qin, Y. ‘No county left behind?’ The distributional impact of high-speed rail upgrades in China. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 17, 489–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, S.; Kong, D.; Wang, Q. High-speed rail, small city, and cost of debt: Firm-level evidence. Pac-Basin. Financ. J. 2019, 57, 101194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Lin, Y. Geographic proximity, information flows and corporate innovation: Evidence from the high-speed rail construction in China. Pac-Basin. Financ. J. 2020, 61, 101342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Zhang, N.; Li, H.; Strauss, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, X. The influence of the air cargo network on the regional economy under the impact of high-speed rail in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlfeldt, G.; Feddersen, A. From periphery to core: Measuring agglomeration effects using high-speed rail. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 18, 355–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, D.; Li, J.; Wu, M. High-speed railways and collaborative innovation. Reg. Sci. Urban. Econ. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickerman, R.W. Can high-speed rail have a transformative effect on the economy? Transp. Policy 2017, 62, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- John, K.; Knyazeva, A.; Knyazeva, D. Does geography matter? Firm location and corporate payout policy. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 101, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X. The causes and consequences of venture capital stage financing. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 101, 132–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Kim, J.B.; Qiu, A.A.; Zang, Y. Geographic proximity between auditor and client: How does it impact audit quality? Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2012, 31, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P.C.; Tan, H. Geographic proximity and analyst coverage decisions: Evidence from IPOs. J. Account. Econ. 2015, 59, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, C.J. The geography of equity analysis. J. Financ. 2005, 60, 719–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chan, K.C. Does high speed rail enhance financial development? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gu, X.; Gao, Y.; Lan, T. Sustainability with high-speed rails: The effects of transportation infrastructure development on firms’ CSR performance. J. Contemp. Account. Ec. 2021, 17, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Guo, X.; Zhao, L. How does transportation infrastructure improve corporate social responsibility? Evidence from high-speed railway openings in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Liu, L.; Liu, G. High-speed rail, tourist mobility, and firm value. Econ. Model. 2020, 90, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, L. Effects of high-speed rail on sustainable development of urban tourism: Evidence from discrete choice model of Chinese tourists’ preference for city destinations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Z.; Li, R.; Peng, D.; Kong, Q. China-European railway, investment heterogeneity, and the quality of urban economic growth. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Du, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Seeing is believing: Do analysts benefit from site visits? Rev. Acc. Stud. 2016, 21, 1245–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, A.; Lei, Z. Will China’s airline industry survive the entry of highspeed rail? Res. Transport. Econ. 2012, 35, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givoni, M. Development and impact of the modern high-speed train: A review. Transport. Rev. 2006, 26, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, W. Need for speed: High-speed rail and firm performance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, L.; Ma, G.; Xu, L.C. Hayek, local information, and commanding heights: Decentralizing state-owned enterprises in China. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 2455–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coval, J.D.; Moskowitz, T.J. Home bias at home: Local equity preference in domestic portfolios. J. Financ. 1999, 54, 2045–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Hauswald, R. Distance and private information in lending. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 2757–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J.; Massa, M. Local ownership as private information: Evidence on the monitoring-liquidity trade-off. J. Financ. Econ. 2007, 83, 751–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opie, W.; Tian, G.G.; Zhang, H.F. Corporate pyramids geographical, distance, and investment efficiency of Chinese state-owned enterprises. J. Bank. Financ. 2019, 99, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubick, T.R.; Lockhart, G.B.; Mills, L.F.; Robinson, J.R. IRS and corporate taxpayer effects of geographic proximity. J. Account. Econ. 2017, 63, 428–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivkovic, Z.; Weisbenner, S. Local does as local is: Information content of the geography of individual investors’ common stock investments. J. Financ. 2005, 60, 267–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauswald, R.; Marquez, R. Competition and strategic information acquisition in credit markets. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2006, 19, 967–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Du, F.; Wang, B.Y.; Wang, X. Do corporate site visits impact stock prices? Contemp. Account. Res. 2019, 36, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petersen, M.A.; Rajan, R.G. Does distance still matter? The information revolution in small business lending. J. Financ. 2002, 57, 2533–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Defond, M.L.; Francis, J.R.; Hallman, N.J. Awareness of SEC enforcement and auditor reporting decisions. Contemp. Account. Res. 2018, 35, 277–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, B.C.; Ramalingegowda, S.; Yeung, P.E. Hometown advantage: The effects of monitoring institution location on financial reporting discretion. J. Account. Econ. 2011, 52, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Xia, B.; Chen, Y.; Ding, N.; Wang, J. Environmental uncertainty, financing constraints and corporate investment: Evidence from China. Pac-Basin. Financ. J. 2021, 70, 101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, W.; Tang, Z.; Gao, X.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, X. The impact of government role on high-quality innovation development in mainland China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levinsohn, J.; Petrin, A. Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobervables. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2003, 70, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xie, R.; Ma, C.; Fu, Y. Market-based environmental regulation and total factor productivity: Evidence from Chinese enterprises. Econ. Model. 2021, 95, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Liu, Y. Air quality uncertainty and earnings management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P.M.; Sloan, R.; Sweeney, A. Detecting earnings management. Account. Rev. 1995, 70, 193–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P.M.; Kothari, S.P.; Watts, R.L. The relation between earnings and cash flows. J. Account. Econ. 1998, 25, 133–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roychowdhury, S. Earnings management through real activities manipulation. J. Account. Econ. 2006, 42, 335–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Fan, G.; Hu, L. Marketization Index of China’s Provinces; NERI Report 2018; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Mean | Std. | 25% | Median | 75% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | 8.0693 | 1.0107 | 7.3718 | 7.9937 | 8.6751 |

| HSR | 0.5369 | 0.4986 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| SIZE | 22.0823 | 1.2655 | 21.1786 | 21.9083 | 22.7974 |

| LEV | 0.4593 | 0.2003 | 0.3063 | 0.4631 | 0.6124 |

| ROE | 0.0493 | 0.1552 | 0.0247 | 0.0641 | 0.1113 |

| Growth | 0.1703 | 0.3354 | 0.0098 | 0.0940 | 0.2210 |

| BtoM | 0.6507 | 0.2489 | 0.4572 | 0.6624 | 0.8549 |

| Cashflow | −1.5407 | 4.1458 | −1.0495 | −0.4042 | −0.1787 |

| STATE | 0.4810 | 0.4996 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| DUAL | 5.0777 | 7.8133 | 0 | 0 | 9.1299 |

| Top1 | 35.8807 | 15.2457 | 23.7800 | 33.6600 | 46.6300 |

| EM_Accrual | 0.0118 | 0.0995 | −0.0392 | 0.0112 | 0.0611 |

| EM_Real | 0.0002 | 0.1974 | −0.0929 | 0.0097 | 0.1043 |

| GDPgrt | 0.1171 | 0.0510 | 0.0833 | 0.1027 | 0.1483 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| TFP | TFP | |

| HSR | 0.0276 *** | 0.0214 *** |

| (3.5223) | (2.9283) | |

| SIZE | 0.6138 *** | 0.6351 *** |

| (128.5846) | (129.3674) | |

| LEV | 0.7733 *** | 0.6611 *** |

| (32.6781) | (27.8619) | |

| ROE | 0.9779 *** | 0.9327 *** |

| (27.3383) | (27.3119) | |

| Growth | −0.1446 *** | −0.1175 *** |

| (−10.9278) | (−9.5345) | |

| BtoM | −0.1126 *** | −0.1931 *** |

| (−6.3459) | (−9.0936) | |

| Cashflow | 0.0120 *** | 0.0093 *** |

| (11.7626) | (9.5945) | |

| STATE | −0.0304 *** | 0.0173 ** |

| (−3.5952) | (2.1599) | |

| DUAL | 0.0026 *** | 0.0009 ** |

| (5.2446) | (2.0964) | |

| Top1 | 0.0017 *** | 0.0023 *** |

| (6.2637) | (9.6472) | |

| GDPgrt | 0.7348 *** | 0.2207 * |

| (8.7863) | (1.6953) | |

| INDUSTRY FE | NO | YES |

| YEAR FE | NO | YES |

| Intercept | −5.9160 *** | −6.4900 *** |

| (−59.1043) | (−63.7267) | |

| N | 26,245 | 26,245 |

| Adj R2 | 0.6579 | 0.7326 |

| F | 4827.65 | 1205.62 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | EM_Accrual | TFP | TFP | EM_Real | TFP | |

| HSR | 0.0214 *** | −0.0042 *** | 0.0199 *** | 0.0214 *** | −0.0059 ** | 0.0203 *** |

| (2.9283) | (−3.3569) | (2.7287) | (2.9283) | (−2.2373) | (2.7870) | |

| EM_Accrual | −0.3638 *** | |||||

| (−8.8824) | ||||||

| EM_Real | −0.1862 *** | |||||

| (−9.6910) | ||||||

| SIZE | 0.6351 *** | 0.0040 *** | 0.6365 *** | 0.6351 *** | −0.0233 *** | 0.6307 *** |

| (129.3674) | (4.8196) | (129.9852) | (129.3674) | (−12.6853) | (128.6847) | |

| LEV | 0.6611 *** | −0.0351 *** | 0.6483 *** | 0.6611 *** | 0.1410 *** | 0.6873 *** |

| (27.8619) | (−9.2629) | (27.3622) | (27.8619) | (17.9775) | (28.8338) | |

| ROE | 0.9327 *** | 0.1670 *** | 0.9934 *** | 0.9327 *** | −0.2061 *** | 0.8943 *** |

| (27.3119) | (31.9889) | (28.3383) | (27.3119) | (−20.8581) | (26.1328) | |

| Growth | −0.1175 *** | 0.0344 *** | −0.1050 *** | −0.1175 *** | 0.0384 *** | −0.1104 *** |

| (−9.5345) | (12.0503) | (−8.4621) | (−9.5345) | (6.1748) | (−8.9154) | |

| BtoM | −0.1931 *** | 0.0074 ** | −0.1904 *** | −0.1931 *** | 0.2108 *** | −0.1538 *** |

| (−9.0936) | (2.1148) | (−8.9747) | (−9.0936) | (26.7579) | (−7.1008) | |

| Cashflow | 0.0093 *** | 0.0010 *** | 0.0096 *** | 0.0093 *** | −0.0007 ** | 0.0092 *** |

| (9.5945) | (6.2406) | (9.9844) | (9.5945) | (−2.0318) | (9.5331) | |

| STATE | 0.0173 ** | −0.0016 | 0.0167 ** | 0.0173 ** | 0.0210 *** | 0.0212 *** |

| (2.1599) | (−1.1974) | (2.0914) | (2.1599) | (7.3687) | (2.6541) | |

| DUAL | 0.0009 ** | −0.0001 | 0.0009 ** | 0.0009 ** | −0.0003 * | 0.0009 ** |

| (2.0964) | (−0.7301) | (2.0550) | (2.0964) | (−1.8874) | (1.9703) | |

| Top1 | 0.0023 *** | −0.0001 ** | 0.0023 *** | 0.0023 *** | −0.0003 *** | 0.0022 *** |

| (9.6472) | (−2.1275) | (9.5335) | (9.6472) | (−3.5132) | (9.4217) | |

| GDPgrt | 0.2207 * | −0.0357 | 0.2078 | 0.2207 * | −0.0070 | 0.2194 * |

| (1.6953) | (−1.5981) | (1.5970) | (1.6953) | (−0.1503) | (1.6899) | |

| INDUSTRY FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| YEAR FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Intercept | −6.4900 *** | −0.0795 *** | −6.5189 *** | −6.4900 *** | 0.2615 *** | −6.4413 *** |

| (−63.7267) | (−4.6086) | (−64.1299) | (−63.7267) | (7.1625) | (−63.4894) | |

| N | 26,245 | 26,245 | 26,245 | 26,245 | 26,245 | 26,245 |

| Adj R2 | 0.7326 | 0.1912 | 0.7337 | 0.7326 | 0.0956 | 0.7338 |

| F | 1205.62 | 69.7400 | 1197.23 | 1205.62 | 34.6514 | 1192.96 |

| Sobel Test | 0.0015 *** (z = 3.164) | 0.0011 ** (z = 2.213) | ||||

| Goodman Test 1 | 0.0015 *** (z = 3.15) | 0.0011 ** (z = 2.204) | ||||

| Goodman Test 2 | 0.0015 *** (z = 3.178) | 0.0011 ** (z = 2.222) | ||||

| Mediating effect | 7.04% | 5.15% | ||||

| The ratio of indirect to direct effects | 7.58% | 5.43% | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TobinQ | EM_Accrual | TobinQ | TobinQ | EM_Real | TobinQ | |

| HSR | 0.0307 ** | −0.0037 *** | 0.0300 ** | 0.0307 ** | −0.0067 *** | 0.0275 * |

| (2.0538) | (−3.0727) | (2.0073) | (2.0538) | (−2.5891) | (1.8462) | |

| EM_Accrual | −0.1890 ** | |||||

| (−2.1445) | ||||||

| EM_Real | −0.4817 *** | |||||

| (−11.3219) | ||||||

| SIZE | −0.1689 *** | 0.0034 *** | −0.1682 *** | −0.1689 *** | −0.0241 *** | −0.1805 *** |

| (−14.9095) | (4.2854) | (−14.8389) | (−14.9095) | (−13.7562) | (−15.9668) | |

| LEV | −0.5603 *** | −0.0371 *** | −0.5673 *** | −0.5603 *** | 0.1375 *** | −0.4941 *** |

| (−10.5565) | (−10.2355) | (−10.6331) | (−10.5565) | (18.2467) | (−9.2775) | |

| ROE | −0.0665 | 0.1650 *** | −0.0353 | −0.0665 | −0.2049 *** | −0.1651 *** |

| (−1.0711) | (33.1355) | (−0.5548) | (−1.0711) | (−21.5499) | (−2.6488) | |

| Growth | 0.5693 *** | 0.0352 *** | 0.5760 *** | 0.5693 *** | 0.0412 *** | 0.5892 *** |

| (18.8639) | (12.6645) | (18.8962) | (18.8639) | (6.8127) | (19.5511) | |

| BtoM | −5.2062 *** | 0.0069 ** | −5.2049 *** | −5.2062 *** | 0.2031 *** | −5.1083 *** |

| (−101.3000) | (2.0539) | (−101.2300) | (−101.3000) | (26.8115) | (−99.0689) | |

| Cashflow | −0.0492 *** | 0.0009 *** | −0.0491 *** | −0.0492 *** | −0.0008 *** | −0.0496 *** |

| (−26.8964) | (5.6353) | (−26.7519) | (−26.8964) | (−2.5769) | (−26.9148) | |

| STATE | −0.2440 *** | −0.0015 | −0.2443 *** | −0.2440 *** | 0.0201 *** | −0.2344 *** |

| (−16.2866) | (−1.1375) | (−16.2978) | (−16.2866) | (7.2662) | (−15.7104) | |

| DUAL | −0.0054 *** | −0.0001 | −0.0054 *** | −0.0054 *** | −0.0004 *** | −0.0056 *** |

| (−6.4283) | (−0.7657) | (−6.4394) | (−6.4283) | (−2.7714) | (−6.6662) | |

| Top1 | 0.0039 *** | −0.0001 ** | 0.0038 *** | 0.0039 *** | −0.0003 *** | 0.0037 *** |

| (8.1860) | (−2.0688) | (8.1500) | (8.1860) | (−3.8780) | (7.8813) | |

| GDPgrt | 0.9272 *** | −0.0365 * | 0.9204 *** | 0.9272 *** | −0.0288 | 0.9134 *** |

| (3.8586) | (−1.6971) | (3.8318) | (3.8586) | (−0.6475) | (3.8064) | |

| INDUSTRY FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| YEAR FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Intercept | 9.4083 *** | −0.0611 *** | 9.3967 *** | 9.4083 *** | 0.2845 *** | 9.5453 *** |

| (40.9787) | (−3.6910) | (40.8847) | (40.9787) | (8.1607) | (41.6470) | |

| N | 28,062 | 28,062 | 28,062 | 28,062 | 28,062 | 28,062 |

| Adj R2 | 0.6440 | 0.1927 | 0.6441 | 0.6440 | 0.0928 | 0.6465 |

| F | 350.1929 | 73.4922 | 345.3974 | 350.1929 | 34.7401 | 346.6463 |

| Sobel Test | 0.0007 ** (z = 1.972) | 0.0032 ** (z = 2.572) | ||||

| Goodman Test 1 | 0.0007 * (z = 1.913) | 0.0032 ** (z = 2.565) | ||||

| Goodman Test 2 | 0.0007 ** (z = 2.036) | 0.0032 *** (z = 2.578) | ||||

| Mediating effect | 2.27% | 10.43% | ||||

| The ratio of indirect to direct effects | 2.32% | 11.64% | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | EM_Accrual | TFP | TFP | EM_Real | TFP | |

| HSR | 0.0801 *** | −0.0061 *** | 0.0781 *** | 0.0801 *** | −0.0099 ** | 0.0782 *** |

| (7.3354) | (−3.1835) | (7.1730) | (7.3354) | (−2.5742) | (7.1879) | |

| EM_Accrual | −0.3231 *** | |||||

| (−5.8704) | ||||||

| EM_Real | −0.1946 *** | |||||

| (−7.3473) | ||||||

| SIZE | 0.6171 *** | 0.0056 *** | 0.6189 *** | 0.6171 *** | −0.0263 *** | 0.6120 *** |

| (89.0689) | (4.7555) | (89.5819) | (89.0689) | (−10.4845) | (88.2966) | |

| LEV | 0.6406 *** | −0.0324 *** | 0.6301 *** | 0.6406 *** | 0.1443 *** | 0.6686 *** |

| (20.0182) | (−6.3031) | (19.7254) | (20.0182) | (13.9138) | (20.6565) | |

| ROE | 0.8832 *** | 0.1664 *** | 0.9369 *** | 0.8832 *** | −0.1823 *** | 0.8477 *** |

| (19.9895) | (23.9288) | (20.6012) | (19.9895) | (−14.3347) | (19.1393) | |

| Growth | −0.1220 *** | 0.0300 *** | −0.1123 *** | −0.1220 *** | 0.0390 *** | −0.1144 *** |

| (−7.7680) | (7.8867) | (−7.1147) | (−7.7680) | (4.7330) | (−7.2546) | |

| BtoM | −0.1074 *** | −0.0038 | −0.1086 *** | −0.1074 *** | 0.2076 *** | −0.0670 ** |

| (−3.8029) | (−0.8007) | (−3.8515) | (−3.8029) | (20.1341) | (−2.3366) | |

| Cashflow | 0.0096 *** | 0.0010 *** | 0.0100 *** | 0.0096 *** | −0.0021 *** | 0.0092 *** |

| (5.5157) | (3.4632) | (5.7283) | (5.5157) | (−3.5306) | (5.2975) | |

| STATE | 0.0068 | −0.0031 | 0.0058 | 0.0068 | 0.0094 ** | 0.0086 |

| (0.6279) | (−1.6376) | (0.5370) | (0.6279) | (2.5401) | (0.7986) | |

| DUAL | 0.0015 *** | −0.0001 | 0.0015 *** | 0.0015 *** | −0.0005 ** | 0.0014 ** |

| (2.6967) | (−0.8574) | (2.6521) | (2.6967) | (−2.4706) | (2.5267) | |

| Top1 | 0.0014 *** | −0.0001 | 0.0014 *** | 0.0014 *** | −0.0005 *** | 0.0013 *** |

| (4.2885) | (−1.0498) | (4.2399) | (4.2885) | (−4.0902) | (4.0129) | |

| GDPgrt | 0.7840 *** | −0.0181 | 0.7782 *** | 0.7840 *** | 0.0401 | 0.7918 *** |

| (4.3161) | (−0.5754) | (4.2870) | (4.3161) | (0.6519) | (4.3714) | |

| INDUSTRY FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| YEAR FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Intercept | −6.2981 *** | −0.0989 *** | −6.3301 *** | −6.2981 *** | 0.3440 *** | −6.2312 *** |

| (−44.1146) | (−4.1199) | (−44.4586) | (−44.1146) | (6.9460) | (−43.7497) | |

| N | 13,993 | 13,993 | 13,993 | 13,993 | 13,993 | 13,993 |

| Adj R2 | 0.7308 | 0.2100 | 0.7317 | 0.7308 | 0.1038 | 0.7321 |

| F | 608.8711 | 42.9796 | 602.2675 | 608.8711 | 20.7214 | 601.2643 |

| Sobel Test | 0.0020 *** (z = 2.901) | 0.0019 ** (z = 2.474) | ||||

| Goodman Test 1 | 0.0020 *** (z = 2.876) | 0.0019 ** (z = 2.457) | ||||

| Goodman Test 2 | 0.0020 *** (z = 2.928) | 0.0019 ** (z = 2.491) | ||||

| Mediating effect | 2.44% | 2.40% | ||||

| The ratio of indirect to direct effects | 2.51% | 2.46% | ||||

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| OLS | PSM_OLS | |

| TFP | TFP | |

| HSR | 0.0214 *** | 0.0224 ** |

| (2.9283) | (2.2288) | |

| SIZE | 0.6351 *** | 0.6376 *** |

| (129.3674) | (84.5414) | |

| LEV | 0.6611 *** | 0.6934 *** |

| (27.8619) | (19.6628) | |

| ROE | 0.9327 *** | 0.9278 *** |

| (27.3119) | (19.2758) | |

| Growth | −0.1175 *** | −0.1111 *** |

| (−9.5345) | (−6.3717) | |

| BtoM | −0.1931 *** | −0.1970 *** |

| (−9.0936) | (−6.4572) | |

| Cashflow | 0.0093 *** | 0.0115 *** |

| (9.5945) | (7.1550) | |

| STATE | 0.0173 ** | 0.0257 ** |

| (2.1599) | (2.2431) | |

| DUAL | 0.0009 ** | 0.0001 |

| (2.0964) | (0.2270) | |

| Top1 | 0.0023 *** | 0.0025 *** |

| (9.6472) | (7.6400) | |

| GDPgrt | 0.2207 * | 0.3128 |

| (1.6953) | (1.5706) | |

| INDUSTRY FE | YES | YES |

| YEAR FE | YES | YES |

| Intercept | −6.4900 *** | −6.5888 *** |

| (−63.7267) | (−41.3042) | |

| N | 26,245 | 20,826 |

| Adj R2 | 0.7326 | 0.7215 |

| F | 1205.62 | 579.9309 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| First Stage | Second Stage | |

| HSR | TFP | |

| Slope | −0.0052 *** | |

| (−3.0829) | ||

| HSR | 3.1754 *** | |

| (2.9074) | ||

| SIZE | −0.0112 *** | 0.6704 *** |

| (−2.7522) | (37.3592) | |

| LEV | 0.1522 *** | 0.1909 |

| (8.5725) | (1.0920) | |

| ROE | 0.0486 ** | 0.7767 *** |

| (2.5185) | (9.0230) | |

| Growth | −0.0180 ** | −0.0594 |

| (−2.0467) | (−1.6367) | |

| BtoM | 0.0813 *** | −0.4597 *** |

| (4.6213) | (−4.3093) | |

| Cashflow | 0.0093 *** | −0.0202 * |

| (10.2204) | (−1.8838) | |

| STATE | −0.0872 *** | 0.2919 *** |

| (−12.9481) | (2.9908) | |

| DUAL | −0.0006 | 0.0027 * |

| (−1.5609) | (1.9169) | |

| Top1 | −0.0006 *** | 0.0043 *** |

| (−3.1442) | (4.4321) | |

| GDPgrt | 0.7997 *** | −2.1112 ** |

| (7.6893) | (−2.3672) | |

| INDUSTRY FE | YES | YES |

| YEAR FE | YES | YES |

| Intercept | 0.1249 | −6.8655 *** |

| (1.5346) | (−22.8105) | |

| N | 26,040 | 26,040 |

| F | 443.9940 | 137.5100 |

| Panel A | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |||||

| Better Business Environment | Poorer Business Environment | |||||

| TFP | TFP | |||||

| HSR | 0.0278 *** | 0.0018 | ||||

| (2.7515) | (0.1638) | |||||

| SIZE | 0.6096 *** | 0.6559 *** | ||||

| (93.0630) | (92.1740) | |||||

| LEV | 0.7663 *** | 0.5758 *** | ||||

| (26.9277) | (18.7423) | |||||

| ROE | 0.9472 *** | 0.8671 *** | ||||

| (27.4646) | (26.7122) | |||||

| Growth | −0.1554 *** | −0.0723 *** | ||||

| (−11.1310) | (−4.9185) | |||||

| BtoM | −0.1379 *** | −0.2500 *** | ||||

| (−4.9308) | (−8.3255) | |||||

| Cashflow | 0.0082 *** | 0.0091 *** | ||||

| (5.4409) | (5.8172) | |||||

| STATE | 0.0205 * | 0.0547 *** | ||||

| (1.8774) | (4.7805) | |||||

| DUAL | 0.0014 ** | 0.0005 | ||||

| (2.3461) | (0.7430) | |||||

| Top1 | 0.0013 *** | 0.0032 *** | ||||

| (3.9477) | (9.1449) | |||||

| GDPgrt | 0.4672 ** | 0.4557 *** | ||||

| (2.1183) | (2.7780) | |||||

| INDUSTRY FE | YES | YES | ||||

| YEAR FE | YES | YES | ||||

| Intercept | −5.9930 *** | −6.9880 *** | ||||

| (−43.6491) | (−48.8259) | |||||

| N | 14,307 | 11,938 | ||||

| Adj R2 | 0.7218 | 0.7531 | ||||

| F | 546.8600 | 536.4757 | ||||

| Mean difference test | Chi2(1) = 3.08 | |||||

| Prob > chi2 = 0.0792 | ||||||

| Panel B | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| TFP | EM_Accrual | TFP | TFP | EM_Real | TFP | |

| HSR | 0.0278 *** | −0.0043 ** | 0.0262 ** | 0.0278 *** | −0.0146 *** | 0.0251 ** |

| (2.6291) | (−2.4728) | (2.4815) | (2.6291) | (−3.9532) | (2.3859) | |

| EM_Accrual | −0.3854 *** | |||||

| (−6.9288) | ||||||

| EM_Real | −0.1851 *** | |||||

| (−7.1554) | ||||||

| SIZE | 0.6096 *** | 0.0034 *** | 0.6109 *** | 0.6096 *** | −0.0229 *** | 0.6054 *** |

| (89.8889) | (3.0647) | (90.3719) | (89.8889) | (−9.0838) | (89.5498) | |

| LEV | 0.7663 *** | −0.0365 *** | 0.7522 *** | 0.7663 *** | 0.1512 *** | 0.7943 *** |

| (23.2135) | (−6.9759) | (22.8589) | (23.2135) | (13.9968) | (23.8401) | |

| ROE | 0.9472 *** | 0.1825 *** | 1.0175 *** | 0.9472 *** | −0.2425 *** | 0.9023 *** |

| (18.2247) | (23.9052) | (19.1859) | (18.2247) | (−15.5349) | (17.3155) | |

| Growth | −0.1554 *** | 0.0349 *** | −0.1420 *** | −0.1554 *** | 0.0497 *** | −0.1462 *** |

| (−9.6792) | (9.2166) | (−8.7563) | (−9.6792) | (6.1303) | (−9.0384) | |

| BtoM | −0.1379 *** | 0.0087 * | −0.1345 *** | −0.1379 *** | 0.2137 *** | −0.0983 *** |

| (−4.7085) | (1.8108) | (−4.6040) | (−4.7085) | (19.5790) | (−3.3003) | |

| Cashflow | 0.0082 *** | 0.0010 *** | 0.0086 *** | 0.0082 *** | −0.0003 | 0.0081 *** |

| (5.7589) | (4.5268) | (6.0489) | (5.7589) | (−0.5722) | (5.7608) | |

| STATE | 0.0205 * | −0.0052 *** | 0.0185 | 0.0205 * | 0.0218 *** | 0.0245 ** |

| (1.8071) | (−2.6978) | (1.6338) | (1.8071) | (5.3891) | (2.1679) | |

| DUAL | 0.0014 ** | 0.0000 | 0.0014 ** | 0.0014 ** | −0.0000 | 0.0014 ** |

| (2.4004) | (0.2799) | (2.4227) | (2.4004) | (−0.2141) | (2.3885) | |

| Top1 | 0.0013 *** | −0.0001 | 0.0012 *** | 0.0013 *** | −0.0001 | 0.0012 *** |

| (3.9588) | (−1.0911) | (3.8935) | (3.9588) | (−1.2111) | (3.8842) | |

| GDPgrt | 0.4672 * | −0.0172 | 0.4606 * | 0.4672 * | 0.0751 | 0.4812 ** |

| (1.9544) | (−0.4285) | (1.9309) | (1.9544) | (0.8837) | (2.0181) | |

| INDUSTRY FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| YEAR FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Intercept | −5.9930 *** | −0.0746 *** | −6.0217 *** | −5.9930 *** | 0.1999 *** | −5.9560 *** |

| (−41.5354) | (−3.1058) | (−41.8396) | (−41.5354) | (3.8463) | (−41.5419) | |

| N | 14,307 | 14,307 | 14,307 | 14,307 | 14,307 | 14,307 |

| Adj R2 | 0.7218 | 0.1873 | 0.7230 | 0.7218 | 0.1054 | 0.7230 |

| F | 611.1233 | 39.6044 | 608.4060 | 611.1233 | 20.2517 | 604.7388 |

| Sobel Test | 0.0017 ** (z = 2.345) | 0.0027 *** (z = 3.561) | ||||

| Goodman Test 1 | 0.0017 ** (z = 2.329) | 0.0027 *** (z = 3.539) | ||||

| Goodman Test 2 | 0.0017 ** (z = 2.362) | 0.0027 *** (z = 3.584) | ||||

| Mediating effect | 5.96% | 9.70% | ||||

| The ratio of indirect to direct effects | 6.34% | 10.75% | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, T.; Xiao, X.; Dai, Q. Transportation Infrastructure Construction and High-Quality Development of Enterprises: Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of High-Speed Railway Opening in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13316. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313316

Zhao T, Xiao X, Dai Q. Transportation Infrastructure Construction and High-Quality Development of Enterprises: Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of High-Speed Railway Opening in China. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13316. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313316

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Tianjiao, Xiang Xiao, and Qinghui Dai. 2021. "Transportation Infrastructure Construction and High-Quality Development of Enterprises: Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of High-Speed Railway Opening in China" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13316. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313316

APA StyleZhao, T., Xiao, X., & Dai, Q. (2021). Transportation Infrastructure Construction and High-Quality Development of Enterprises: Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of High-Speed Railway Opening in China. Sustainability, 13(23), 13316. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313316