The Innovative Response of Cultural and Creative Industries to Major European Societal Challenges: Toward a Knowledge and Competence Base

Abstract

1. Introduction

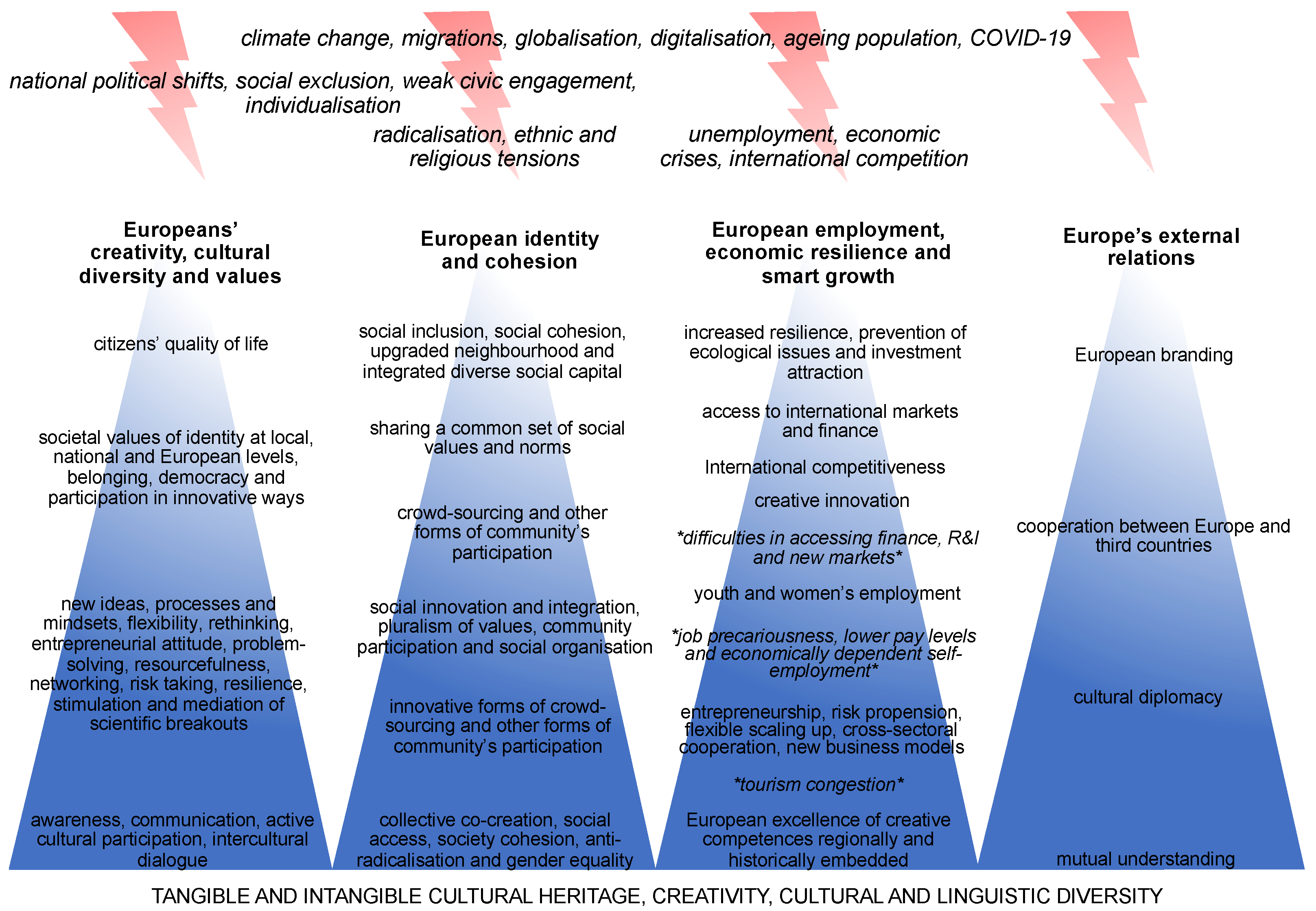

2. Europeans’ Creativity, Cultural Diversity and Values

3. European Identity and Cohesion

4. European Employment, Economic Resilience and Smart Growth

4.1. Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Job Creation

4.2. Cultural Heritage—A European Competitive Advantage

5. A Policy State of the Art of Knowledge and Competence Base in the CCI

5.1. EU Policy for the CCI

5.2. R&I Strategies for Smart Specialization and a Creative Europe

5.3. Horizon 2020—European Framework Program for Research and Innovation

5.4. National and International Promotions for Innovation

6. Toward a Possible EU Policy Framework Enabling Creative Spillovers

7. Discussion

8. Future Research

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- KEA. The Economy of Culture in Europe. 2006. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/culture/library/studies/cultural-economy_en.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Ndou, V.; Schiuma, G.; Passiante, G. Towards a framework for measuring creative economy: Evidence from Balkan countries. Meas. Bus. Excel. 2019, 23, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, I.B.-S.; Herrero-Prieto, L.C. Reliability of creative composite indicators with territorial specification in the EU. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Institute of Innovation and Technology. Potential Future EIT Thematic Areas—Input to the EIT Strategic Innovation Agenda 2021–2027; European Institute of Innovation and Technology: Budapest, Hungary, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Report on a Coherent EU Policy for Cultural and Creative Industries (2016/2072(INI); European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Guide to Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation (RIS3); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stanojev, J.; Gustafsson, C. Smart specialisation strategies for elevating integration of cultural heritage into circular economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comunian, R.; England, L. Creative and cultural work without filters: Covid-19 and exposed precarity in the creative economy. Cult. Trends 2020, 29, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. The concentric circles model of the cultural industries. Cult. Trends 2008, 17, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flew, T. The Creative Industries: Culture and Policy; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Snowball, J.D. Cultural value. In A Handbook of Cultural Economics, 2nd ed.; Towse, R., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, A.C.; Jeffcutt, P. Creativity, Innovation and the Cultural Economy; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2009; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, P.; De Propris, L. A policy agenda for EU smart growth: The role of creative and cultural industries. Policy Stud. 2011, 32, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaro, E. Linking the creative economy with universities’ entrepreneurship: A spillover approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L. Creative Industries and Innovation in Europe. Concepts, Measures and Comparative Case Studies; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Mapping the Creative Value Chains. A Study on the Economy of Culture in the Digital Age; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A New European Agenda for Culture; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro, E. Cultural and creative entrepreneurs. In Culture, Innovation and the Economy; Doyle, J.E., Mickov, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro, E. Art at the crossroads between creativity, innovation, digital technology and business, a case study. In Teaching Cultural Economics; Teaching Economics Series; Bille, T., Mignosa, A., Towse, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 238–240. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, P.L.; Ferilli, G.; Blessi, G.T. From culture 1.0 to culture 3.0: Three socio-technical regimes of social and economic value creation through culture, and their impact on European cohesion policies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, I. Cultural and creative industries concept—A historical perspective. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 110, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Impulse Paper on the Role of Cultural and Creative Sectors in Innovating European Industry; European Commission, Directorate General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The Value of Culture and the Creative Industries in Local Development; OECD: Trento, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Poussin, G. Public-private partnerships and the creative sector. Int. Trade Forum Mag. 2009, 4, 39. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. A Coherent EU Policy for Cultural and Creative Industries European Parliament. Resolution of 13 December 2016 (2016/2072(INI)) (2018/C 238/02); European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Horizon 2020—The Framework Programme for Research and Innovation; Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. COM, Brussels (2011) 808 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission-Oriented Research & Innovation in the European Union. A Problem-Solving Approach to Fuel Innovation Led Growth; European Commission, Directorate General for Research and Innovation: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, J. Creative Industries; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sonkoly, G.; Vahtikari, T. Innovation in Cultural Heritage: For an Integrated European Research Policy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshi, H.; McVittie, E. Creative supply-chain linkages and innovation: Do the creative industries stimulate business innovation in the wider economy? Innovation 2009, 11, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benghozi, P.-J.; Salvador, E. How and where the R&D takes place in creative industries? Digital investment strategies of the book publishing sector. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2015, 28, 568–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latilla, V.M.; Frattini, F.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Berner, M. Knowledge management and knowledge transfer in arts and crafts organizations: Evidence from an exploratory multiple case-study analysis. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1335–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominelli, F.; Greffe, X. Intangible cultural heritage: Safeguarding for creativity. City Cult. Soc. 2012, 3, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovchin, S.; Pennycook, A.; Sultana, S. Popular Culture, Voice and Linguistic Diversity: Young Adults On- and Offline; Palgrave-Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spiridon, P.; Kosic, M.; Tuci, B. Creactive youth promoting cultural heritage for tomorrow. Ad Alta J. Interdiscip. Res. 2014, 4, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tafel-Viia, K.; Viia, A.; Terk, E.; Lassur, S. Urban policies for the creative industries: A European comparison. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 796–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrocu, E.; Paci, R. Regional development and creativity. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2012, 36, 354–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateljević, J.; Trivić, J. Economic Development and Entrepreneurship in Transition Economics. Issues, Obstacles and Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fontainha, E.; Lazzaro, E. Cultural and creative entrepreneurs in financial crises: Sailing against the tide? Sci. Ann. Econ. Bus. 2019, 66, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, P.L.; Ferilli, G.; Tavano Blessi, G.; Nuccio, M. Culture as an engine of local development processes: System-wide cultural districts. I: Theory. Growth Chang. 2013, 44, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, P.L.; Ferilli, G.; Tavano Blessi, G.; Nuccio, M. Culture as an engine of local development processes: System-wide cultural districts. II: Prototype cases. Growth Chang. 2013, 44, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, P.L. Culture 3.0: A New Perspective for the EU 2014–2020 Structural Funds Programming. Available online: http://www.eenc.info/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/pl-sacco_culture-3-0_CCIsLocal-and-Regional-Development_final.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Sacco, P.L.; Tavano Blessi, G.; Nuccio, M. Culture as an Engine of Local Development Processes: System-Wide Cultural Districts; Working Paper; University IUAV of Venice: Venice, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Buscema, P.M.; Ferilli, G.; Gustafsson, C.; Sacco, P.L. The complex dynamic evolution of cultural vibrancy in the region of Halland, Sweden. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2020, 43, 159–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaro, E. Prospettive economiche delle tecnologie dell’informazione per il patrimonio culturale e la creatività. Knowl. Transf. Rev. Focus Cult. Creat. Ind. 2018, 1, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Vinas, S.M. Contemporary theory of conservation. Stud. Conserv. 2002, 47, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Luiten, E.; Renes, H.; Stegmeijer, E. Heritage as sector, factor and vector: Conceptualizing the shifting relationship between heritage management and spatial planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1654–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galison, P. Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, C. The Halland Model—A Trading Zone for Building Conservation in Concert with Labour Market Policy and the Construction Industry, Aiming at Regional Sustainable Development; Chalmers University of Technology: Göteborg, Sweden, 2009; Volume 13, p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- Regeringen. Kulturarvspolitik. Regeringens Proposition 2016/2017:116; Regeringen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Feilden, B.M. Conservation of Historic Buildings, 3rd ed.; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK; Burlington, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stedman, M.; Lichfield, N. Economics in urban conservation. Geogr. J. 1990, 156, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijkamp, P. Evolution measurement in conservation planning. J. Cult. Econ. 1991, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rypkema, D.D. The Economics of Historic Preservation: A Community Leader’s Guide; PlaceEconomics: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R. Be interested and beware: Joining economic valuation and heritage conservation. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2008, 14, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardi, G.; Amirtahmasebi, R. The Economics of Uniqueness: Investing in Historic City Cores and Cultural Heritage Assets for Sustainable Development; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CHCFE Consortium. Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe; International Culture Center: Krakow, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ripp, M. A Metamodel for Heritage-Based Urban Development; Brandenburg University of Technology: Cottbus, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stanojev, J.; Gustafson, C. Towards cultural heritage-based innovation strategies by evolution of the knowledge triangle of research, education and business innovation. Built Herit. J. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Fusco Girard, L.; Ost, C.; Saleh, R. Evolution criteria for circular adaptive reuse of Cultural Heritage. BDC Bull. Centro Calza Bini 2017, 17, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Micheletti, S.; Bosone, M. A Participatory approach for “circular” adaptive reuse of cultural heritage. Building a heritage community in Salerno, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickerill, T. Investment leverage for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.; Saleh, R. The adaptive reuse of cultural heritage in European circular city plans: A systematic review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszczynska-Kurasinska, M.; Domaradzka, A.; Wnuk, A.; Oleksy, T. Intrinsic value and perceived essentialism of culture heritage sites as tools for planning interventions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J. Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd is Driving the Future of Business; Crown: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lafleur, B.; Maas, W.; Mors, S. Courageous Citizens: How Culture Contributes to Social Change; European Cultural Foundation: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Degen, M.; Garcia, M. The transformation of the ‘Barcelona model’: An analysis of culture, urban regeneration and governance. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 1022–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, S. Presumption in art. Am. Behav. Sci. 2012, 56, 550–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzmann, K. Culture, creativity and spatial planning. Town Plan. Rev. 2004, 75, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullally, G. Shakespeare, the structural funds and sustainable development reflections on the Irish experience. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2004, 17, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contò, F.; Vrontis, D.; Fiore, M.; Thrassou, A. Strengthening regional identities and culture through wine industry cross border collaboration. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1788–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černevičiūtė, J.; Strazdas, R.; Kregždaitė, R.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Cultural and creative industries for sustainable postindustrial regional development: The case of Lithuania. J. Int. Stud. 2019, 12, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Noccia, F. Moving towards the circular economy/city model: Which tools for operationalizing this model? Sustainability 2019, 11, 6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, C. Conservation 3.0—Cultural Heritage as a driver for regional growth. Ric. Sci. Tecnol. Inf. 2019, 9, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Foord, J. Strategies for creative industries: An international review. Creat. Ind. J. 2009, 1, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, N.; Petridou, E. Venture performance factors in creative industries: A sample of female entrepreneurs. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 33, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leovardis, C.; Banha, M.; Cismaru, D.M. Between motherhood and entrepreneurship: Insights on women entrepreneurs in the creative industries. In Strategica: Challenging the Status Quo in Management and Economics; Bratianu, C., Zbuchea, A., Vitelar, A., Eds.; National University of Political Studies and Public Administration: Bucharest, Romania, 2018; pp. 1383–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, C. Women and the creative industries: Exploring the popular appeal. Creat. Ind. J. 2009, 2, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culture Statistics—Cultural Employment. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Culture_statistics_-_cultural_employment#Cultural_employment_by_sex.2C_age_and_educational_attainment (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Lee, B.; Kelly, L. Cultural leadership ideals and social entrepreneurship: An international study. J. Soc. Entrep. 2019, 10, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devece, C.; Peris-Ortiz, M.; Rueda-Armengot, C. Entrepreneurship during economic crisis: Success factors and paths to failure. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5366–5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culture Statistics—Cultural Enterprises. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Culture_statistics_-_cultural_enterprises (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Hotho, S.; Champion, K. Small businesses in the new creative industries: Innovation as a people management challenge. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, I.; Pachhi, C.; Vita, S. Co-working spaces in Milan: Location patterns and urban effects. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Guerra, P.; Marques, T.S. Entrepreneurial mission of an academic creative incubator: The creative industries pole of Science and Technology Park of Oporto’s University. In Smart Specialization Strategies and the Role of Entrepreneurial Universities; Caseiro, N., Domingos, S., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- O′Connor, J. The Cultural and Creative Industries: A Review of the Literature; Arts Council England: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Towse, R. Economics of copyright collecting societies and digital rights: Is there a case for a centralised digital copyright exchange? Rev. Econ. Res. Copyr. Issues 2012, 9, 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, G.; Bustinza, O.F.; Vendrell-Herrero, F. Copyright and creation: Repositioning the argument. Strat. Dir. 2014, 30, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzani, G.; Pozzi, F.; Dagnino, F.; Katos, A.V.; Katsouli, E.F. Innovative technologies for intangible cultural heritage education and preservation: The case of i-Treasures. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2017, 21, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Pardo, T.A.; Nam, T. What makes a city smart? Identifying core components and proposing an integrative and comprehensive conceptualization. Inf. Polity 2015, 20, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Vassilopoulou, P.; Stergioulas, L. Technology roadmap for the creative industries. Creat. Ind. J. 2017, 10, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, G.; Bustinza, O.F.; Vendrell-Herrero, F. Servitisation and value co-production in the UK music industry: An empirical study of Consumer Attitudes. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangematin, V.; Sapsed, J.; Schüßler, E. Disassembly and reassembly: An introduction to the special issue on digital technology and creative industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 83, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoneman, P. Soft Innovations: Economics, Product Aesthetics and the Creative Industries; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, A. Digitalization for Value Creation; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt-Grau, A.; Busquin, P.; Clausse, G.; Gustafsson, C.; Kolar, J.; Lazzaro, E.; Smith, B.; Spek, T.; Thurley, S.; Tufano, F. Getting Cultural Heritage to Work for Europe—H2020 Expert Group in Cultural Heritage; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, C. Research for Culture Committee—Best Practices in Sustainable Management and Safeguarding of Cultural Heritage in the EU; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Council of European Union. Council Conclusions of 21 May 2014 on Cultural Heritage as a Strategic Resource for a Sustainable Europe; Council of Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Council. Cultural Heritage as a Strategic Resource for a Sustainable Europe. Council Conclusions of 21 May 2014 (2014/C 183/08); European Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Juul, M. Tourism and the European Union. Recent Trends and Policy Developments; European Parliamentary Research Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nypan, T.; Warr, A. The economic taskforce. In The Commission initiative for improved cultural statistics (ESS-net). In Proceedings of the 10th Annual Meeting of the European Heritage Heads Forum (EHHF), Dublin, Ireland, 20–22 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Valentina, V.; Marius-Răzvan, S.; Ioana-Alexandra, L.; Stroe, A. Innovative valuing of the cultural heritage assets. Economic implication on local employability, small entrepreneurship development and social inclusion. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 188, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durieux-Paillard, S. Differences in language, religious beliefs and culture: The need for culturally responsive health services. In Migration and Health in the European Union; Rechel, B., Mladovsky, P., Devillé, W., Rijks, B., Petrova-Benedict, R., McKee, M., Eds.; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2012; pp. 203–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Psychogiopoulou, E. Cultural Governance and the European Union: Protecting and Promoting Cultural Diversity in Europe; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Figueira, C. A Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council: Towards an EU Strategy for International Cultural Relations, by the European Commission, 2016. Cult. Trends 2017, 26, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von der Leyen, U. A Union that Strives for More: My Agenda for Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Towards an EU Strategy for International Cultural Relations; Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council of 8 June 2016—JOIN(2016) 29 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Agenda for Culture in a Globalizing World; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication “Europe 2020: A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth”—COM(2010) 2020); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Setting Out the EU Approach to Standard Essential Patents; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Horizon 2020 Cultural Heritage and European Identities—List of Projects 2014–2017; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Year of Cultural Heritage. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Implmnetation, Results and Overall Assessment of the European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjS0dHo6LL0AhXJl2oFHRBwCDoQFnoECBoQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.heritagecouncil.ie%2Fcontent%2Ffiles%2FEuropean-Year-of-Cultural-Heritage-2018-Report-Ireland.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1n7_SEAO7NQciRT0wTqvc9 (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Council of European Union. Council Conclusions on Participatory Governance of Cultural Heritage; Council of Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Towards an Integrated Approach Cultural Heritage for Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Conticelli, E.; De Luca, C.; Egusquiza, A.; Santangelo, A.; Tondelli, S. Inclusion of migrants for rural regeneration through cultural and natural heritage valorization. In Planning, Nature and Ecosystem Services; Gargiulo, C., Zoppi, C., Eds.; FedOAPress: Naples, Italy, 2019; pp. 323–332. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, C.; Tondelli, S.; Åberg, H.E. The Covid-19 pandemic effects in rural areas. TeMa J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2020, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda. 2017. Available online: http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/NUA-English.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- UNESCO. Recommendations on Historic Urban Landscapes. 2013. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul/ (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- UNCTAD-UNDP. Creative Economy Report 2010. 2010. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditctab20103_en.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- UNDP-UNESCO. Creative Economy Report 2013. Special Edition Widening Local Development Patheways. 2013. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/culture/pdf/creative-economy-report-2013.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- UNCTAD. Creative Economy Outlook. Trends in International Trade in Creative Industries 2002–2015 Coutnry Profiles 2005–2014. 2015. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditcted2018d3_en.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- ICOMOS. ICOMOS Annual Report 2015; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, F.H.; Mulatero, F. Knowledge Policy in the EU: From the Lisbon Strategy to Europe 2020. J. Knowl. Econ. 2010, 1, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heger, T.; Bub, U. The EIT ICT Labs—Towards a leading European innovation initiative. IT Inf. Technol. 2012, 54, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, G.; Leceta, J.M.; Tejero, A. Impact of the EIT in the creation of an open educational ecosystem: UPM experience. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 10, 178–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leceta, J.M.; Könnölä, T. Fostering entrepreneurial innovation ecosystems: Lessons learned from the European Institute of Innovation and Technology. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinkorova, J.; Topolcan, O. Knowledge and innovation communities, new potential for biomedical research in Europe. EPMA J. 2014, 5, A144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gustafsson, C.; Lazzaro, E. Input to EIT’s Strategic Innovation Agenda: Future EIT Thematic Area of Culture, Cultural Heritage and Creative Industries—Expert Analysis; European Institute of Innovation and Technology: Budapest, Hungary, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Boosting the Innovation Talent and Capacity of Europe; Proposal for a Decision of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Strategic Innovation Agenda of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) 2021–2027; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen, I. Towards transnational academic capitalism. High. Educ. 2012, 64, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Economic Modelling System: Assessment of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) Investments in Innovation and Human Capital. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/74bde06e-e591-11e9-9c4e-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- OECD. Innovating Education and Educating for Innovation: The Power of Digital Technologies and Skills; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. Curating the ‘third place’? Coworking and the mediation of creativity. Geoforum 2017, 82, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaina, V.; Karoewski, I.P.; Kuhn, S. European Identity Revisited. New Approaches and Recent Empirical Evidence; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, A.; Petersson, B. Temporality in the construction of EU identity. Eur. Soc. 2003, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ham, P. Europe’s postmodern identity: A critical appraisal. Int. Politics 2001, 38, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Graham, B.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. Pluralising the Pasts: Heritage, Identity and Place in Multicultural Societies; Pluto: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey David, C. Heritage pasts and heritage presents. Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. In Cultural Heritage: Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies; Smith, L., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rodney, H. Understanding the Politics of Heritage; The Open University: Milton Keynes, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Borin, E.; Donato, F.; Sinapi, C. Financial sustainability of small- and medium-sized enterprises in the cultural and creative sector: The role of funding. In Entrepreneurship in Culture and Creative Industries; FGF Studies in Small Business and Entrepreneurship; Innerhofer, E., Pechlaner, H., Borin, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A.; Haenlein, M. Rulers of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of artificial intelligence. Bus. Horizons 2020, 63, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P. Persistent Creativity: Making the Case for Art, Culture and the Creative Industries; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. LAB—FAB—APP Investing in the European Future We Want; Report of the Independent High-Level Group on Maximising the Impact of EU Research & Innovation Programmes; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro, E.; Noonan, D. Cultural and creative crowdfunding: A comparative analysis of regulatory frameworks in Europe and the USA. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020, 27, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaro, E.; Noonan, D. Cultural entrepreneurship in a supportive ecosystem: The contribution of crowdfunding regulation. In Cultural Initiatives for Sustainable Development: Management, Participation and Entrepreneurship in the Cultural and Creative Sector; Book Series: Contributions to Management Science; Demartini, P., Marchegiani, L., Marchiori, M., Schiuma, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vang, J. The spatial organization of the news industry: Questioning assumptions about knowledge externalities for clustering of creative industries. Innovation 2007, 9, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampel, J.; Germain, O. Creative industries as hubs of new organizational and business practices. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2327–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, E.; Sacco, P.L.; Blessi, G.T.; Cerutti, R. The impact of culture on the individual subjective well-being of the Italian population: An exploratory study. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2010, 6, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Why European Higher Education Systems Must be Modernised? MEMO/06/190 Date: 10 May 2006; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gustafsson, C.; Lazzaro, E. The Innovative Response of Cultural and Creative Industries to Major European Societal Challenges: Toward a Knowledge and Competence Base. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313267

Gustafsson C, Lazzaro E. The Innovative Response of Cultural and Creative Industries to Major European Societal Challenges: Toward a Knowledge and Competence Base. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313267

Chicago/Turabian StyleGustafsson, Christer, and Elisabetta Lazzaro. 2021. "The Innovative Response of Cultural and Creative Industries to Major European Societal Challenges: Toward a Knowledge and Competence Base" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313267

APA StyleGustafsson, C., & Lazzaro, E. (2021). The Innovative Response of Cultural and Creative Industries to Major European Societal Challenges: Toward a Knowledge and Competence Base. Sustainability, 13(23), 13267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313267