Do National Policies Translate into Local Actions? Analyzing Coherence between Climate Change Adaptation Policies and Implications for Local Adaptation in Nepal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Policy Coherence: Definitions and Analytical Frameworks

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection Tools and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Content and Coherence of Climate Change Policies and Strategies of Nepal

4.1.1. Focus of Climate Policies and Strategies

4.1.2. Provisions and Instruments in the Policies

4.1.3. Institutional Structure for Policy Implementation

Central Level Institutions

Provincial-Level Institutions

District Level/Local-Level Institutions

4.1.4. Coherence between Climate Change Policy, NAPA, PAPA, and LAPA

4.2. Reflection of Climate Change Policies’ Provisions in Local Adaptation Actions and Complimentary Community Practices

4.2.1. Assessing Climate Vulnerability and Local Impacts

4.2.2. Responding to Locally Identified Impacts

4.2.3. Shifting Local Priority toward Climate Issues

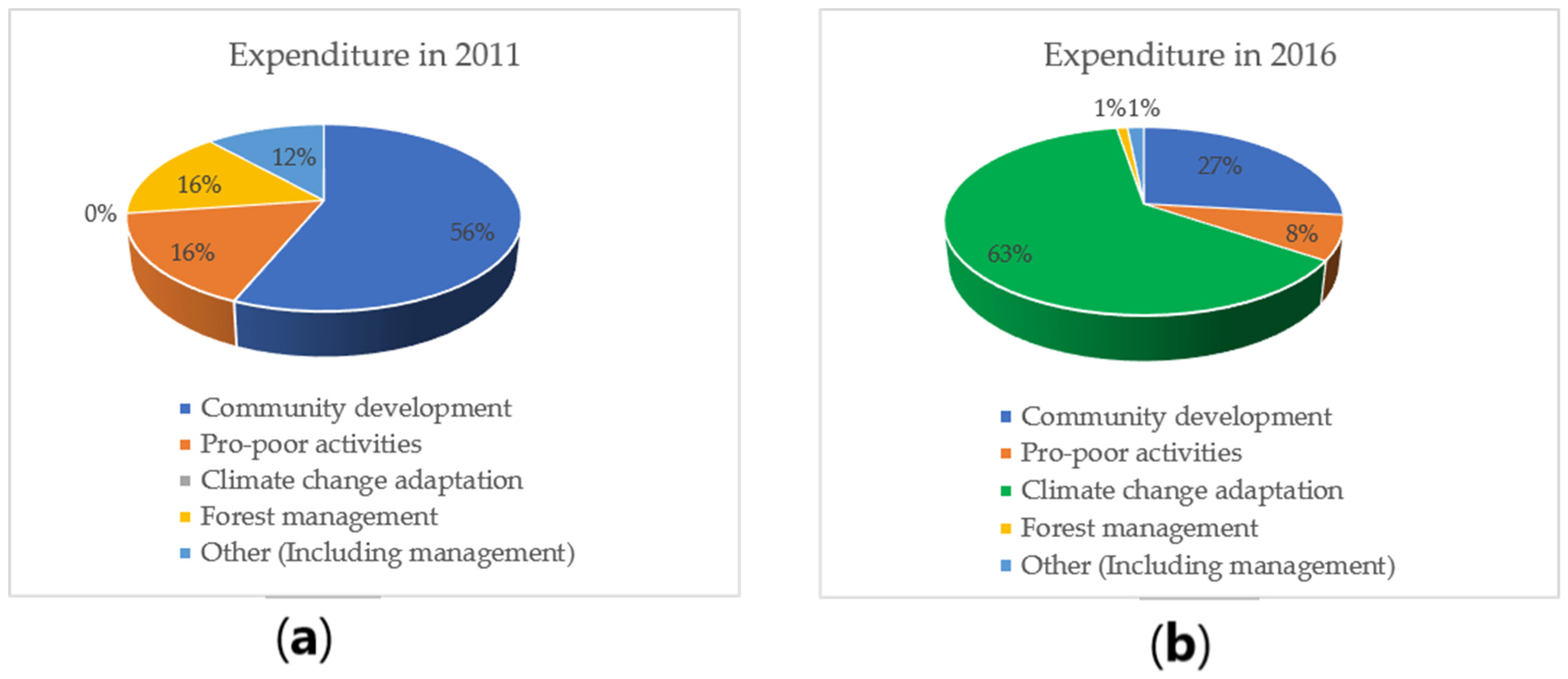

4.2.4. Overall CAPA Activities Linking to Policy Priority

4.2.5. CFUG’s Practices as Complementary to Climate Change Policy 2019

4.3. National Policies and Local Implementation: Gaps between Climate Change Policy 2019, NAPA, and LAPA

5. Discussions

5.1. How Are Climate Change Policies Coherent? Contents and Provisions of Climate Change Policy 2019, NAPA, and LAPA

5.2. How Climate Change Policy Provisions Are Translated into Local Actions? A Case of CAPA Implementation by CFUG

5.3. Gaps Hindering the Policy Coherence and the Localization of National Policies

5.3.1. Ambiguous Institutional Framework for Implementation and Coordination

5.3.2. Insufficient Information, Knowledge and Capacity Related to Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Measures for Policy Implementation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudhary, P.; Aryal, K.P. Global warming in Nepal: Challenges and policy imperatives. J. For. Livelihood 2009, 8, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, B.; Burton, I.; Klein, R.J.; Wandel, J. An anatomy of adaptation to climate change and variability. In Societal Adaptation to Climate Variability and Change; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 223–251. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; Huq, S.; Brown, K.; Conway, D.; Hulme, M. Adaptation to climate change in the developing world. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2003, 3, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Regmi, B.R. Adverse impacts of climate change on development of Nepal: Integrating adaptation into policies and activities. Bangladesh Cent. Adv. Stud. 2004, 69, 447–451. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Article 2 and Article 11. Text of the Convention. 1992. Available online: http://unfccc.int/essential_background/convention/background/items/1353.php (accessed on 18 February 2017).

- Schipper, L.; Pelling, M. Disaster risk, climate change and international development: Scope for, and challenges to, integration. Disasters 2006, 30, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GoN. National Framework on Local Adaptation Plans for Action; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Forest and Environment (MoFE): Singhdurbar Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019.

- Rai, J.K.; Gurung, G.B.; Pathak, A. Climate Change Adaptation in MSFP Working Districts: Lessons from LAPA and CAPA Preparation and Implementation in the Koshi Hill Region; ForestAction Nepal and RRN: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pyakurel, D.; Bista, R.; Ghimire, L. Document Review and Analysis of Community Adaptation Plan of Action and Local Adaptation Plan of Action. Final Report Submitted to Multi-Stakeholder Forestry Programme-Service Support Unit (MSFP-SSU); MSCFP: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- GoN. Climate Change Policy, 2019; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Forest and Environment (MoFE): Singhdurbar Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019.

- Neupane, P.R. Viability Assessment of Jurisdictional Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) Implementation in Vietnam; Universität Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Neupane, P.R.; Wiati, C.B.; Angi, E.M.; Köhl, M.; Butarbutar, T.; Reonaldus; Gauli, A. How REDD+ and FLEGT-VPA processes are contributing towards SFM in Indonesia—The specialists’ viewpoint. Int. For. Rev. 2019, 21, 460–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, F.; Silveira, S.; Khatiwada, D. Land allocation to meet sectoral goals in Indonesia—An analysis of policy coherence. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraiappah, A.K.; Bhardwaj, A. Measuring Policy Coherence among the MEAs and MDGs; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, M.; Zamparutti, T.; Petersen, J.E.; Nykvist, B.; Rudberg, P.; McGuinn, J. Understanding policy coherence: Analytical framework and examples of sector–environment policy interactions in the EU. Environ. Policy Gov. 2012, 22, 395–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.; Dougill, A.; Pardoe, J.; Vincent, K. Policy brief Policy coherence for sustainable development in sub-Saharan Africa. Target 2018, 17, 1. [Google Scholar]

- UN. General Assembly Takes Action on Second Committee Reports by Adopting 37 Texts. 2016. Available online: https://www.un.org/press/en/2016/ga11880.doc.htm (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- UNFCCC. Adoption of the Paris agreement. UN, D.C. & Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Pearson, L.; Pelling, M. The UN Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030: Negotiation process and prospects for science and practice. J. Extrem. Events 2015, 2, 1571001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Rayner, J. Design principles for policy mixes: Cohesion and coherence in ‘new governance arrangements’. Policy Soc. 2007, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.J.; Song, A.M.; Morrison, T.H. Policy coherence with the small-scale fisheries guidelines: Analysing across scales of governance in Pacific small-scale fisheries. In The Small-Scale Fisheries Guidelines; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, T.G. Fisheries subsidies in China: Quantitative and qualitative assessment of policy coherence and effectiveness. Mar. Policy 2016, 68, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development 2018: Towards Sustainable and Resilient Societies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, M.; Milner, J.; Williams, J.L. Translating Policy Intent into Action. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103199/translating-policy-intent-into-action-a-framework-to-facilitate-implementation-of-agricultural-policies-in-africa_0.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Ranabhat, S.; Ghate, R.; Bhatta, L.D.; Agrawal, N.K.; Tankha, S. Policy coherence and interplay between climate change adaptation policies and the forestry sector in Nepal. Environ. Manag. 2018, 61, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentle, P.; Maraseni, T.N. Climate change, poverty and livelihoods: Adaptation practices by rural mountain communities in Nepal. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 21, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulal, H.B.; Brodnig, G.; Thakur, H.K.; Green-Onoriose, C. Do the poor have what they need to adapt to climate change? A case study of Nepal. Local Environ. 2010, 15, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Boyd, E. Exploring social barriers to adaptation: Insights from Western Nepal. Glob. Environ. Chang. Hum. Policy Dimens. 2011, 21, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, P.; Keenan, R.J.; Ojha, H.R. Community institutions, social marginalization and the adaptive capacity: A case study of a community forestry user group in the Nepal Himalayas. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 92, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, S.; Sigdel, E.; Sthapit, B.; Regmi, B. Tharu Community’s Perception on Climate Changes and Their Adaptive Initiations to Withstand Its Impacts in Western Terai of Nepal. Int. NGO J. 2011, 6, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Regmi, B.R.; Bhandari, D. Climate change adaptation in Nepal: Exploring ways to overcome the barriers. J. For. Livelihood 2013, 11, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, S.H.; Nightingale, A.J.; Eakin, H. Reframing adaptation: The political nature of climate change adaptation. Glob. Environ. Chang. Hum. Policy Dimens. 2015, 35, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, H.R.; Ghimire, S.; Pain, A.; Nightingale, A.; Khatri, D.B.; Dhungana, H. Policy without politics: Technocratic control of climate change adaptation policy making in Nepal. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silwal, P.; Roberts, L.; Rennie, H.G.; Lexer, M.J. Adapting to climate change: An assessment of local adaptation planning processes in forest-based communities in Nepal. Clim. Dev. 2019, 11, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, N.S.; Ojha, H.; Karki, R.; Gurung, N. Integrating climate change adaptation with local development: Exploring institutional options. J. For. Livelihood 2013, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, K.; Laudari, H.K.; Neupane, P.R.; Maraseni, T. Who shapes the environmental policy in the global south? Unpacking the reality of Nepal. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 121, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerlings, H.; Stead, D. The integration of land use planning, transport and environment in European policy and research. Transport. Policy 2003, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis, L.; Fuller, S.; Klein, R.; Henwood, M.; Plowden, W.; Webb, A.; Whittingham, P.; Wistow, G. Joint Approaches to Social Policy: Rationality and Practice; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/DAC. DAC Guidelines-Poverty Reduction; OECD Publications: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Improving Policy Coherence and Integration for Sustainable Development: A Checklist; OECD: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, A.; Pierre-Antoine, D. Poverty and Policy Coherence: A Case Study of Canada’s Relations with Developing Countries; North-South Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- May, P.J.; Jones, B.D.; Beem, B.E.; Neff-Sharum, E.A.; Poague, M.K. Policy coherence and component-driven policymaking: Arctic policy in Canada and the United States. Policy Stud. J. 2005, 33, 37–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.J.; Sapotichne, J.; Workman, S. Policy coherence and policy domains. Policy Stud. J. 2006, 34, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.N. Public Policy Analysis: An Introduction; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, M.; Wiklund, H.; Finnveden, G.; Jonsson, D.K.; Lundberg, K.; Tyskeng, S.; Wallgren, O. Analytical framework and tool kit for SEA follow-up. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2009, 29, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M. Mission impossible: The European Union and policy coherence for development. Eur. Integr. 2008, 30, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.; Bynum, N.; Johnson, E.; King, U.; Mustonen, T.; Neofotis, P.; Oettle, N.; Rosenzweig, C.; Sakakibara, C.; Shadrin, V.; et al. Linking Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge of Climate Change. Bioscience 2011, 61, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoebink, P. A tale of two countries: Perspectives from the South on the coherence of Eu policies. In Tales of Development: People, Power and Space; Hoebink, P., Slootweg, S., Smith, L., Eds.; Assen: Van Gorcum, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Siitonen, L. Theorising Politics behind Policy Coherence for Development (PCD); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Briassoulis, H. Policy integration for complex policy problems: What, why and how. Presented at the 2004 Berlin Conference “Greening of Policies: Interlinkages and Policy Integration”, Berlin, Germany, 3–4 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman, L. Promoting Policy and Institutional Coherence for the Sustainable Development Goals. Presented at 17th Session of the UN Committee of Experts on Public Administration, New York, NY, USA, 23–27 April 2018; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1476289/files/E_C-16_2018_2-EN.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Kivimaa, P.; Mickwitz, P. Making the Climate Count: Climate Policy Integration and Coherence in Finland; Finnish Environment Institute: Helsinki, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaba, F.K.; Quinn, C.H.; Dougill, A.J. Contribution of forest provisioning ecosystem services to rural livelihoods in the Miombo woodlands of Zambia. Popul. Environ. 2013, 35, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkonen, M.; Huttunen, S.; Primmer, E.; Repo, A.; Hildén, M. Policy coherence in climate change mitigation: An ecosystem service approach to forests as carbon sinks and bioenergy sources. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 50, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, W.P. Studies in government and public policy (USA). In Cultivating Congress: Constituents, Issues, and Interests in Agricultural Policymaking; University Press of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, A.P. Complementarity theory: Why human social capacities evolved to require cultural complements. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 4, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayers, J.; Forsyth, T. Community-Based Adaptation to Climate Change: Strengthening Resilience through Development. Environment 2009, 51, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, S.; Reid, H. Community-Based Adaptation: A Vital Approach to the Threat Climate Change Poses to the Poor; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Khatri, D.B.; Bista, R.; Gurung, N. Climate change adaptation and local institutions: How to connect community groups with local government for adaptation planning. J. For. Livelihood 2013, 11, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate change 2014: Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. In Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Barros, V.R., Field, C.B., Dokken, D.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-PartB_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2018).

- MoE. National Adaptation Program of Actions; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Environment: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2010.

- MoE. Climate Change Policy, 2011; Ministry of Environment, Government of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2011.

- Agrawal, A. The Role of Local Institutions in Adaptation to Climate Change; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.K. The political economy of climate change governance in the Himalayan region of Asia: A case study of Nepal. Reg. Environ. Gov. Interdiscip. Perspect. Theor. Issues Comp. Des. 2011, 14, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dixit, A. Ready or Not: Assessing Institutional Aspects of National Capacity for Climate Change Adaptation; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- MoITFE. Provincial Adaptation Program of Action (PAPA) to Climate Change (Draft); Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment, Gandaki Province: Pokhara, Nepal, 2019.

- MoE. Local Adaptation Plan of Action (LAPA) Framework; Ministry of Environment, Government of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2011.

- Rupantaran Nepal. Consolidating Learning of Local and Community Based Adaptation Planning: Implications for Adaptation Policy and Practice. Available online: http://rupantaran.org.np/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Consolidating-learning-of-local-and-community-based-adaptation-planning-Implications-for-Adaptation-Policy-and-Practice.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Jamarkattel, B.K. Institutional Mechanism for Intervention on Climate Change Adaptation at the Local Level. Master’s Thesis, Tribhuvan University, Institute of Forestry, Pokhara, Nepal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- GoN. The Guideline for Community Forestry Development Programme; Forest Department, C.F.D., Ed.; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation (MoFSC): Babarmahal Kathmandu, Nepal, 2014.

- Ayers, J. Understanding the Adaptation Paradox: Can Global Climate Change Adaptation Policy be Locally Inclusive? The London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Helvetas, N. Nepal’s climate change polices and plans: Local communities’ perspective. Environ. Clim. Ser. 2011, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, M.W. Learning from experience: Lessons from policy implementation. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1987, 9, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GoN. The Environment Protection Act, 2019; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Forest and Environment (MoFE): Singhdurbar Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019.

- GoN. Local Government Operation Act, 2017; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2017.

- GoN. Forest Act 2019; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Forest and Environment (MoFE): Singhdurbar Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019.

- Tiwari, K.R.; Rayamajhi, S.; Pokharel, R.K.; Balla, M.K. Does Nepal’s Climate Change Adaption Policy and Practices Address Poor and Vulnerable Communities. JL Pol’y Glob. 2014, 23, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, H.; Huq, S. Mainstreaming community-based adaptation into national and local planning introduction. Clim. Dev. 2014, 6, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, M.I.; Dougill, A.J.; Stringer, L.C.; Vincent, K.E.; Pardoe, J.; Kalaba, F.K.; Mkwambisi, D.D.; Namaganda, E.; Afionis, S. Climate change adaptation and cross-sectoral policy coherence in southern Africa. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 18, 2059–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Blanco, C.R.; Burns, S.L.; Giessen, L. Mapping the fragmentation of the international forest regime complex: Institutional elements, conflicts and synergies. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2019, 19, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, M.; Brown, K.; Rosendo, S. Policy misfits, climate change and cross-scale vulnerability in coastal Africa: How development projects undermine resilience. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Perrin, N.; Chhatre, A.; Benson, C.; Cononen, M. Climate Policy Processes, Local Institutions and Adaptation Actions: Mechanisms of Translations and Influence. Social Development Paper 119; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Darjee, K.B.; Ankomah, G.O. Climate Change Adaptation Practices of Forest Dependent Poor People: Comparative Study of Nepal and Ghana. In Proceedings of the Science Policy Gap Regarding Informed Decisions in Forest Policy and Management. What Scientific Information Are Policy Makers Really Interested in?: Proceedings of the 6th International DAAD Workshop, Santiago, Chile, 12–20 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pokharel, B.K.; Branney, P.; Nurse, M.; Malla, Y.B. Community forestry: Conserving forests, sustaining livelihoods and strengthening democracy. J. For. Livelihood 2007, 6, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- CBS. National Climate Change Impact Survey 2016. A Statistical Report; Central Bureau of Statistics: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2017.

- GoN. Nepal Disaster Report; Ministry of Home Affairs (MoHA) and Disaster Preparedness Network-Nepal (DPNet-Nepal): Kathmandu Nepal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, A.J. A socionature approach to adaptation: Political transition, intersectionality, and climate change programmes in Nepal. In Climate Change Adaptation and Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, S.; Brown, K. Sustainable Adaptation to Climate Change; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, D.M. Local Adaptation to Climate Change: A Case Study Among the Indigenous Palaw’ans in the Philippines. In Climate Change in the Asia-Pacific Region; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Laidler, G.J. Inuit and Scientific Perspectives on the Relationship Between Sea Ice and Climate Change: The Ideal Complement? Clim. Chang. 2006, 78, 407–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Perrin, N. Climate adaptation, local institutions and rural livelihoods. Adapt. Clim. Chang. Threshold. Values Gov. 2009, 350–367. Available online: https://www.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=dsD5UdpEOPsC&oi=fnd&pg=PA350&dq=Climate+adaptation,+local+institutions+and+rural+livelihoods&ots=4zh_smhkqS&sig=vOrbL8s44o9jFt_7j8STkzusSxU (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Amaru, S.; Chhetri, N.B. Climate adaptation: Institutional response to environmental constraints, and the need for increased flexibility, participation, and integration of approaches. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 39, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodima-Taylor, D.; Olwig, M.F.; Chhetri, N. Adaptation as innovation, innovation as adaptation: An institutional approach to climate change. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 33, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, B.R.; Star, C.; Leal, W. Effectiveness of the Local Adaptation Plan of Action to support climate change adaptation in Nepal. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2016, 21, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, P.; Gauli, A.; Mundhenk, P.; Köhl, M. Developing indicators for participatory forest biodiversity monitoring systems in South Sumatra. Int. For. Rev. 2020, 22, 464–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J. Vulnerability does not just fall from the sky: Toward multi-scale pro-poor climate policy. In Handbook on Climate Change and Human Security; Edward Elgar Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gentle, P.; Thwaites, R.; Race, D.; Alexander, K. Differential impacts of climate change on communities in the middle hills region of Nepal. Nat. Hazards 2014, 74, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamarkattel, B.K.; Dhakal, S.; Joshi, J.; Gautam, D.R.; Hamal, S.S. Responding to Differential Impacts: Lessons from Hariyo Ban Program in Nepal; CARE Nepal: Dhobighat Nepal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers, J.M.; Huq, S. The value of linking mitigation and adaptation: A case study of Bangladesh. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Forests and Environment. Nepal’s National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Process: Reflecting on Lessons Learned and the Way Forward. The NAP Global Network, Action on Climate Today (ACT) and Practical Action Nepal; Government of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2018.

- Bishokarma, N.K. Capacity Gaps and Needs Analysis Report: Livelihoods and Governance Sector; Climate Change Management Division, National Adaptation Plan Formulation Process: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The Food and Agriculture Organization. An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security. Food Security Information for Action. Practical Guides; The Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Edame, G.; Anam, B.E.; Fonta, W.; Duru, E. Climate Change, Food Security and Agricultural Productivity in Africa: Issues and Policy Directions. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 1, 205–223. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Declaration of the World Summit on Food Security. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/k6050e/k6050e.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Ochieng, J.; Kirimi, L.; Mathenge, M. Effects of climate variability and change on agricultural production: The case of small scale farmers in Kenya. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 77, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichamu, E.A.; Ziro, J.S.; Palaniappan, G.; Ross, H. Climate change perceptions and adaptations of smallholder farmers in Eastern Kenya. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 2663–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, J.P.; Sapkota, T.B.; Khurana, R.; Khatri-Chhetri, A.; Rahut, D.B.; Jat, M.L. Climate change and agriculture in South Asia: Adaptation options in smallholder production systems. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 5045–5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B. Resilience in agriculture through crop diversification: Adaptive management for environmental change. BioScience 2011, 61, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, E.; Mirasgedis, S.; Sarafidis, Y.; Vitaliotou, M.; Lalas, D.; Theloudis, I.; Giannoulaki, K.-D.; Dimopoulos, D.; Zavras, V. Climate change impacts and adaptation options for the Greek agriculture in 2021–2050: A monetary assessment. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 16, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, N. The Future for Climate Finance in Nepal. Report for CDDE Bangkok; Overseas Development Insitutte (ODI): London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, S. Adaptation United: Building Blocks from Developing Countries on Integrated Adaptation; Tearfund: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dongol, Y.; Heinen, J.T. Pitfalls of CITES implementation in Nepal: A policy gap analysis. Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, S.; Borie, M.; Chilvers, J.; Esguerra, A.; Heubach, K.; Hulme, M.; Lidskog, R.; Lövbrand, E.; Marquard, E.; Miller, C. Towards a reflexive turn in the governance of global environmental expertise. The cases of the IPCC and the IPBES. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2014, 23, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, M. Problems with making and governing global kinds of knowledge. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhout, J.; Beyers, J.; Braun, C.; Hanegraaff, M.; Lowery, D. Making inference across mobilisation and influence research: Comparing top-down and bottom-up mapping of interest systems. Political Stud. 2018, 66, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkhout, J.; Lowery, D. Short-term volatility in the EU interest community. J. Eur. Public Policy 2011, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.J.; da Silva Hyldmo, H.; Ford, R.M.; Larson, A.M.; Keenan, R.J. Guinea pig or pioneer: Translating global environmental objectives through to local actions in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia’s REDD+ pilot province. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Bokelmann, W.; Dunn, E.S. Determinants of Farmers’ Perception of Climate Change: A Case Study from the Coastal Region of Bangladesh. Am. J. Clim. Chang. 2017, 6, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.N. | Data Collection Tools | Events (No) | Participants (No) | Men (No) | Women (No) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Household survey (semi-structured interviews) | 61 | 61 (25%) * | 38 | 23 |

| 2 | Focus group discussions | 4 | 109 (45%) * | 58 | 51 |

| 3 | Key informant interviews | 11 | 11 | 7 | 4 |

| 4 | Expert interviews | 17 | 17 | 15 | 2 |

| S.N. | Vulnerability | No of HHs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||

| 1 | Very high | 9 | 11 | 20 |

| 2 | High | 22 | 4 | 26 |

| 3 | Moderate | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| 4 | Low | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Total | 38 (62%) | 23 (38%) | 61 | |

| SN | Organizations | Number | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ministry of Forest and Environment (MoFE) (Then) | 3 | Experts |

| 2 | Department of Forest and Soil Conservation (DoFSC) | 2 | Experts |

| 3 | REDD Implementation Centre | 1 | Experts |

| 4 | Climate change adaptation projects, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and national non-governmental organizations (NGOs) | 11 | Experts |

| 5 | Federation of Community Forestry Users Nepal (FECOFUN), ex-chairperson of CFUG | 4 | Key informants |

| 6 | Local climate change facilitators | 2 | Key informants |

| 7 | Health technicians | 2 | Key informants |

| 8 | Local entrepreneurs | 3 | Key informants |

| Policy Documents | Focus of Goal/Objectives | Policy Provisions and Instruments | Implementing Actors (Institutional Responsibility) | Policy Coherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Change Policy, 2019 |

|

|

|

|

| National Adaptation Program of Action, 2010 |

|

|

| |

| Provincial Adaptation Program of Action, 2019 |

|

|

| |

| Framework for Local Adaptation Plan of Action, 2019 |

|

|

|

| Principal Institutional Mechanisms | Level | Project/Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Village Forest Coordination Committee (VFCC), Agriculture Forest and Environment Coordination Committee (AEFCC) | LAPA | Livelihoods & Forestry Program/ Department for International Development (LFP/DFID) and Interim Forestry Project/Multi-stakeholder Forestry Program (FP/MSFP): from 2011 to 2016 |

| CFUGs and public land management groups | CAPA | |

| Village Energy Environment and Climate Change Coordination Committee (VEECCCC) | LAPA | Nepal Climate Change Support Program/Government of Nepal (NCCSP/GON-European Union/Department for International Development (EU/DFID) |

| CFUGs | CAPA | Hariyo Ban Program/ United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Nepal |

| Village Climate Change Coordination Committee (VC4) | LAPA | Initiative for Climate Change Adaptation/(ICCA/USAID) |

| VFCC | LAPA | |

| CFUG and Farmers Group (FG) | CAPA | |

| VC4 | LAPA | Creating Community Climate Change Capacity (5C/Adventist Development and Relief Agency-ADRA-Australia and Rupantaran Nepal) |

| Cooperatives | CAPA | |

| CFUGs and groups of poor and vulnerable communities | CAPA | CARE Nepal |

| Source: [68,69] |

| Impacts | Agriculture Crops Loss | Landslide/Erosion | Water Deficiency | Fodder Scarcity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very high | 9 (15%) | 5 (8%) | 47 (77%) | 0 (0%) |

| High | 39 (64%) | 8 (13%) | 11 (18%) | 3 (5%) |

| Medium | 12 (20%) | 34 (55%) | 3 (5%) | 12 (20%) |

| Low | 1 (2%) | 14 (23%) | 0(0%) | 46 (75%) |

| SN | Infrastructures (Unit) | Before 2011 | After 2011 till 2017 | Total | HHs Benefited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Earthen road (km) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 180 |

| 2 | Walking trails (km) | 2 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 200 |

| 3 | Water reservoirs tank (no.) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 190 |

| 4 | Water source protection (no.) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 202 |

| 5 | Water tap (no.) | 0 | 72 | 72 | 72 |

| 6 | Water pond (no.) | 2 | 17 | 19 | 19 |

| 7 | Rainwater harvest (no. of household) | 20 | 200 | 220 | 220 |

| 8 | Pumping water from river (no.) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 20 |

| 9 | Improved cooking stoves (no.) | 20 | 130 | 130 | 150 |

| 10 | Check dam/Gabion box (no.) | 0 | 45 | 45 | 65 |

| 11 | Fire lines (meter) | 2 | 3 | 5 | 242 |

| 12 | Nursery (no.) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 180 |

| Climate Change Policy and NAPA’s Thematic Priority | Locally Implemented Measures (CAPA) | Implementation Level |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Agriculture and Food security | Drought resistant crop e.g., Ghaiya | Household (HH) |

| Kitchen garden | HH | |

| 2. Forests and Biodiversity | Plantation | Community/Group |

| Fire line in the forest | Community/Group | |

| Improve cooking stove | HH | |

| Nursey promotion | HH | |

| 3. Water resources and Energy | Water reservoir tank | Community/Group |

| Water pond | Community/Group | |

| Pumping water from river | Community/Group, HH | |

| Rain water harvest | HH | |

| 4. Climate-induced disasters | Check dam for landslide/erosion control | Community/Group, HH |

| Trail improvement | Community/Group, HH | |

| Forest plantation | Community/Group | |

| 5. Public health | Water taps at households | HH |

| Improve cooking stove | HH | |

| Kitchen garden-for vegetable | ||

| 6. Urban settlements and Infrastructure | Earthen road improvement | Community/Group |

| Walking trail improvement | Community/Group/HH | |

| Justice and Equity | Allocate patch of forest | HH (poorest of the poor HH) |

| Supply of timber quantity reduced from 30 cubic feet/HH per annum to 22 cubic feet/HH per annum | Promote forest/support vulnerable | |

| interest free loan | Poor |

| CFUG’s Activities Implemented while Executing the Forest Management Operational Plan | Complementing Areas of Climate Change Policies (Complementary to the Policy) |

|---|---|

| Well-being ranking | Vulnerability assessment (Climate Change Policy 2019, NAPA, PAPA, LAPA) |

| Pro-poor forest product distribution | Priority to poor and climate vulnerable people, distributional equity |

| Allocation of forest land to small groups of the poorest of the poor CFUG members | Contribute to reducing vulnerability of poor people, distributional equity |

| Interest-free loan for income generation activities | Access to finance or loan particularly for vulnerable and poor people |

| Establishment of local saving and credit cooperatives | Emergency use for all |

| Policy Provision | Gaps and Contradictions in Implementation | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| NAPA does not spell out any separate plan for adaptation; rather, it presumes that sectoral ministries would mainstream the climate change adaptation into their sectoral plans. | Although LAPA emphasized integrating climate change adaptation into local development planning, it has focused on the development of separate climate change adaptation plans. | Created confusion of providing a proper institutional framework for integrating an adaptation program of line ministries into locally developed climate change adaptation plans. |

| The Climate Change Policy 2019 does not explicitly determine the implementing unit; however, it emphasized that the local adaptation plan was intended to households and the community. “Adaptation measures will be adopted in line with local and indigenous knowledge, skills and technologies by identifying climate change affected households, communities and risk zones (Climate Change Policy 2019)”. However, NAPA is clear about implementing units that local level groups can implement as adaptation programs. “Program/project implementation through existing community level organization/s like CFUG, different farmers groups, irrigation groups and other interest group (NAPA 2010)”. | LAPA emphasizes that local governments ought to prepare and implement adaptation programs. “Local government will prepare climate friendly adaptation plan and implement (LAPA 2019)”. LAPA suggests to select and prioritize adaption measures at the ward, municipality, and rural municipality level. | Role of community-level institutions has been overlooked/negated, because LAPA does not recognize CAPAs. |

| 80% of climate budget should reach the local community. “Mobilization of at least 80 percent of amount will be ensured for implementation of programs at the local level (Climate Change Policy 2019)”. | No clear mechanism for expenditure and authority. | Vulnerable people lack access to available funding. More expense in district level meeting, workshop, etc. |

| Food security and technology development for agriculture promotion. “Food security, nutrition and livelihoods will be improved by adopting [a] climate-friendly agriculture system (Climate Change Policy 2019)”. | Lack of concrete program at the local level for food production and security (in LAPA framework). | Duration of food insufficiency has been increased at a local level. Kept lands fallow due to the high insurgency of drought period (lack of introducing drought-tolerant crops). |

| FUG’s CAPA translated most of the policy prioritized actions mentioned in Climate Change Policy 2019 and NAPA. | However, CAPA are not legitimized as an implementing unit in the LAPA framework. DFO does not take the responsibility to approve it. Progress of the CAPA is not reflected in any of the government official reports. | Lack of funding for CAPA implementation Majority of the CAPA became functionless due to lack of funding after accomplishing the first duration (dormant). Struggling for legitimacy. |

| Capacity development of local government authorities including DFOs. “Capacity of relevant governmental, non-governmental and academic institutions and community associations/organizations of all three levels will be enhanced to mainstream climate resilience into development programs (Climate Change Policy 2019)”. | No clear mechanism and program for capacity development of local government authorities. | Communities rely on temporary project’s staff. Lack of coordination with government authority. Paucity of local government authority’s participation in the CAPA process. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Darjee, K.B.; Sunam, R.K.; Köhl, M.; Neupane, P.R. Do National Policies Translate into Local Actions? Analyzing Coherence between Climate Change Adaptation Policies and Implications for Local Adaptation in Nepal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313115

Darjee KB, Sunam RK, Köhl M, Neupane PR. Do National Policies Translate into Local Actions? Analyzing Coherence between Climate Change Adaptation Policies and Implications for Local Adaptation in Nepal. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313115

Chicago/Turabian StyleDarjee, Kumar Bahadur, Ramesh Kumar Sunam, Michael Köhl, and Prem Raj Neupane. 2021. "Do National Policies Translate into Local Actions? Analyzing Coherence between Climate Change Adaptation Policies and Implications for Local Adaptation in Nepal" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313115

APA StyleDarjee, K. B., Sunam, R. K., Köhl, M., & Neupane, P. R. (2021). Do National Policies Translate into Local Actions? Analyzing Coherence between Climate Change Adaptation Policies and Implications for Local Adaptation in Nepal. Sustainability, 13(23), 13115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313115