Abstract

Rural revitalization to promote sustainable rural development is a key strategy promoted by the Communist Party of China. We conducted a comprehensive policy analysis to explore the development of sustainable rural education for promoting rural revitalization in China. Integrity, openness, and endogeneity are critical in the development of sustainable rural education. We investigated the formulation and implementation of sustainable development policies supporting rural education in China through an in-depth analysis of the rural education policy circle (policy design, content, and implementation) and administered a survey among rural education administrators and teachers to elicit their perspectives. Education personnel employed in rural areas within 10 provinces, including school and education administrators, teaching staff and researchers, and teachers (in kindergartens, primary schools, and middle schools) were recruited for the study. A total of 741 questionnaires were sent out and returned (a recovery rate of 100%). Our findings indicated that the policy design was unreasonable, and its focus on rural-based care was inadequate. Moreover, integration and symbiosis of policy content was lacking, and the governance system was also inadequate, leading to poor policy implementation associated with insufficient support of teacher resources. In addition to addressing the above issues, we suggest that the policy should have a rural orientation to enhance integration and symbiosis, with a focus on building and consolidating the ranks of rural teachers.

1. Introduction

Rural revitalization is a major component of strategic planning designed by the Communist Party of China to promote sustainable rural development. In 2017, A rural revitalization strategy was proposed at the 19th National Congress for the following reasons: Issues concerning agriculture, rural areas, and farmers are fundamental to the national economy and people’s livelihoods, and we must always make solving these issues a top priority in the work of the whole Party [1,2]. We should give priority to the development of agriculture and rural areas, establish and improve systems, mechanisms and policies for integrated urban–rural development, and accelerate the modernization of agriculture and rural areas in accordance with the general requirements of thriving industries, livable ecosystems, civilized local customs, effective governance and a well-off life [3,4,5].

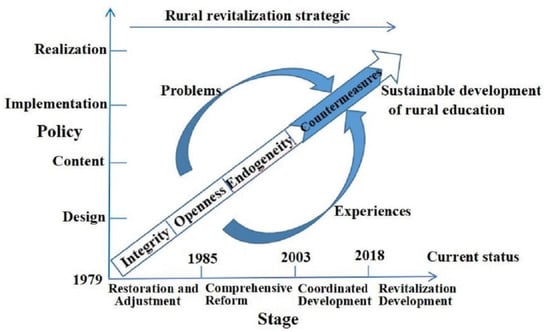

We therefore conducted an analysis of policies that have been implemented to promote rural revitalization in China through the sustainable development of rural education. The paper is organized as follows. Section 1 focuses on the sustainable development of rural education. Section 2 presents a review of historical policies for promoting the sustainable development of rural education in China. Section 3 describes the use of quantitative methods for exploring stakeholders’ perspectives, notably those of education administrators and teachers in rural areas within 10 provinces, who included school and education administrators, teaching staff and researchers, and teachers (at kindergartens, primary schools, and middle schools). Section 4 explores issues faced in the formulation of policies to promote the sustainable development of rural education in China. Section 5 offers concluding remarks relating to the study (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The outline of the sustainable rural education development for rural revitalization in China.

Strategic Relationships between the Sustainable Development of Rural Education and Rural Revitalization

Rural education in China refers to education imparted in rural areas, covering towns and villages below the county level within the administrative structure. The sustainable development of rural education is an essential component in the process of bringing about rural transformation and development [6,7]. Rural revitalization and sustainably designed rural education mutually reinforce each other, with the former providing a political, economic, cultural, and ecological foundation for the latter’s development, which in turn, can promote the construction of rural politics, the economy, culture, and ecology. In other words, these two processes are internally related: the sustainable development of rural education plays an important strategic role in fostering rural revitalization, while rural revitalization importantly promotes the sustainable development of rural education. In the 1990s, the concept of sustainable development gained widespread acceptance and became a universal goal worldwide. Core values driving the sustainable development of rural education are integrity, openness, and endogenous development [8,9]. These values are briefly discussed below.

Integrity refers to the integrated development of rural education and society, with the revitalization of rural education being a “sub-project” under the overall national strategy of rural revitalization, and rural education being one dimension of rural society. The strategy of rural revitalization encompasses content relating to the revitalization of rural education. In September 2018, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued “The Strategic Plan for Rural Revitalization (2018–2022),” which clearly states that “we should adhere to comprehensive rural revitalization, make overall plans for rural economic, political, cultural, social, ecological, and Party building, and give priority to the development of rural education”. In sum, the sustainable development of rural education and rural revitalization are holistically related, with sustainable rural development being an essential part of rural revitalization [10,11].

Openness refers to the coordinated development of rural education and society. The sustainable development of rural education evidently does not take place in isolation; rather, it should be the outcome of the coordinated development of rural education and society. Within the strategy of rural revitalization, the sustainable development of rural education clearly reveals characteristics of openness, reflected in inputs and outputs within a continuous flow of materials, energy, and information between the rural education system and other subsystems of rural society [12,13]. In conjunction with a continuous process of adjusting rural social, political, economic, cultural, and ecological developmental strategies, the rural education system absorbs materials, abilities, and information, makes timely adjustments relating to the strategy for developing rural education and actively responds to new requirements and areas of support required to achieve rural revitalization [14]. At the same time, through the training of personnel as well as through cultural inheritance and social services, the rural education system provides material resources, energy, and information, including human and cultural resources and intellectual support needed to foster rural revitalization. Thus, the sustainable development of rural education and rural revitalization occurs synergistically within open, two-way interactions.

Endogeneity refers to the humanistic development of rural education and society. The sustainable development of rural education must be an endogenous process. Human capital in education is an endogenous and not an exogenous factor. Endogenous development of rural education critically focuses on the development of people [15,16]. Moreover, rural human capital comprising people and human modernization is the key factor driving the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy. Accordingly, the sustainable development of rural education and rural revitalization are essentially compatible, demonstrating a natural internal fit. Both foreground the sustainable development of people and promote rural education and society as endogenous, human-oriented development projects through the sustainable development of people [17,18]. Sustainable development of rural education revitalizes rural communities, providing an endogenous engine of rural revitalization, with rural education being an important carrier and driving force of the revitalization of rural communities.

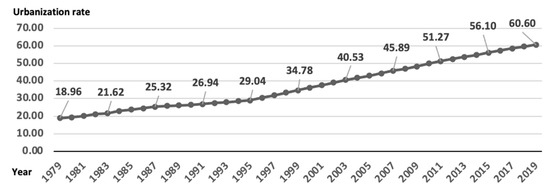

Data available at the National Bureau of Statistics reveal that since the initiation of China’s reform and opening-up process, the urbanization process has accelerated, with the urbanization rate rising from 18.96% in 1979 to 60.60% in 2019, reflecting an increase of 41.64 percentage points (see Figure 2). By the end of 2019, China’s total rural population had reached 551.62 million, accounting for 39.40% of the country’s total population. In the process of rapid urbanization, large proportions of rural populations migrate to cities. Consequently, the rural human capital base is increasingly eroded and weakened, and the dualistic urban–rural structure becomes increasingly prominent. Therefore, the revitalization of rural communities has become the top priority within rural revitalization programs and strategies. The sustainable development of rural education plays a crucial and strategic role in the revitalization of rural communities, notably through rural vocational education and community education. China’s central government concentrates on promoting the sustainable development of rural talent, including re-educating farmers, rural operators, and managers and increasing the stock and quality of rural human capital.

Figure 2.

Changes of China’s urbanization rate since the reform and opening (1979–2019).

Sustainable development of rural education boosts the revitalization of rural culture. The unique social ecology, which refers to pursing the social sustainable development environment, of the countryside sustains the culture and civilization of the Chinese nation. Revitalization of rural culture is naturally inseparable from the sustainable development of rural education. Using local teaching materials and the design of local courses, rural education serves to revive a declining rural culture not only enabling the preservation of its traditional roots but also contributing to its formative influence in shaping the contemporary rural culture [19].Throughout rural cultural responsibility education practice, and changes in the rural construction service process, a five-fold initiation, rise, radical development, transition, and peak has been generally experienced [20]. Practical experience has demonstrated that rural education plays an important role in the development of rural culture, transmitting memories and the traditional heritage of village culture. Moreover, it facilitates the resolution of urban and rural cultural conflict and provides a cultural space for engaging fruitfully with rural cultural dilemmas [21]. Sustainable development of rural education facilitates the realization of the comprehensive revitalization of rural areas, which encompasses rural politics, economy, culture, society, and ecology [22]. Rural education is the first step in the process of rural revitalization and the endogenous driving force of this process. The construction of rural politics, economics, culture, society, and ecologies requires human resources for which an urban education alone is inadequate [23].

Rural education can facilitate comprehensive revitalization of rural areas through the provision of a base education, that is, a vocational education that leads to improved technical skills; a community education that generates rural human resources, and through the cultivation of positive sentiments towards rural areas [24]. It generates local human resources with the capabilities of implementing comprehensive rural revitalization that, in turn, can strengthen rural democracy. The Chinese Communist Party attaches considerable importance to the strategic prioritization and development of rural education and to the provision of all-round strategic support for the sustainable development of rural education through policies, resources, and institutional mechanisms. The sustainable development of rural education has been strategically prioritized under the rural revitalization strategy, which entails policy support for the prioritized development of rural education and aims to bridge existing shortcomings in rural education. Policies such as the 13th Five-Year Plan for Poverty Reduction through Education, “Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Deepening Reform and Standardizing Development of Preschool Education” and the “East–West Cooperation Action Plan for Vocational Education (2016–2020)” have been enacted to promote the sustainable development of rural education [25].

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

We conducted an in-depth investigation of the formulation and implementation of sustainable development policies for rural education in China. Specifically, we examined the rural education policy circle (policy design, content, and implementation) followed by rural education administrators and teachers in ten Chinese provinces. Applying descriptive and content analyses and an analysis of group differences, we assessed the current situation and issues relating to China’s rural education policy and its sustainable development, providing empirical inputs for its further optimization.

2.2. Research Methods and Tools

We administered a questionnaire-based survey as our primary research tool, which we developed using the Questionnaire Star app. This study includes a total of 741 applied questionnaires. The survey was conducted on Wenjuanxing, an online platform, targeting rural education managers and teachers and seeking their views on the design, content, and implementation of rural education policies, problems encountered, and their suggestions and inputs. The questionnaire, titled “Policy Questionnaire on Sustainable Development of Rural Education in China” was compiled by the research group. It comprised three parts. The first part elicited basic information. The second part entailed a quantitative survey, focusing on policy design, content, and implementation. A total of 14 items were included in the second section, which were scored using a 5-point scale: very consistent (5 points), consistent (4 points), general (3 points), not consistent (2 points), and very inconsistent (1 point). The third section consisted of four open questions designed to elicit the reflections and suggestions of rural education managers and teachers on rural education, rural education policies, and rural teacher development. Cronbach’s α was 0.938; The questionnaire was evaluated by four experts in the field of education, six rural education administrators, and six rural teachers, all of whom agreed that the content validity of the questionnaire was good.

2.3. Research Participants and Data Sources

Education administrators and teachers in rural areas (towns and villages) in 10 provinces were selected as the research participants. They included school and education administrators, teaching and research staff, and teachers (at kindergartens, primary schools, and middle schools). A total of 741 questionnaires were sent out and all 741 were returned, indicating a recovery rate of 100%. A total of 734 samples were obtained after excluding seven invalid questionnaires. Respondents were selected from the following provinces: Guangdong (N = 17), Jilin (N = 24), Zhejiang (N = 17), Hebei (N = 18), Hubei (N = 432), Henan (N = 14), Sichuan (N = 131), Guizhou (N = 35), Yunnan (N = 36), and Xinjiang (N = 10) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample distribution of questionnaires.

2.4. Data Processing Procedures

From 11 August 2021 to 26 August 2021, questionnaires were distributed through the Wenjuanxing platform, and the collected data were inputted, organized, and analyzed using the SPSS 22.0 statistical software.

Description and analysis of differences. Using the descriptive statistics function in SPSS 22.0, we analyzed the scores for five dimensions: policy understanding, design, content, and implementation to gain deeper insights into respondents’ general understanding of the policy to promote the sustainable development of rural education in China. We performed a one-way ANOVA using SPSS 22.0 and analyzed demographic differences relating to views on policy design, content, and implementation to elucidate cognitive differences relating to demographic variables.

Cluster analysis. As a first step, we coded textual data, applying content analysis to analyze and code the responses to the open-ended items in the questionnaire. Following preliminary screening, 256 invalid samples were deleted, and 485 valid samples were retained. We conducted an in-depth analysis of the original text and performed first-order coding. A total of 485 key themes were obtained after we had further condensed the theme. As a second step, we filtered high-frequency key topics using the frequency statistics function in SPSS 22.0 to calculate the frequency of 485 valid key topics. The frequency distribution of these key topics revealed 28 high-frequency key topics with frequencies greater than or equal to six. The total frequency was 447, accounting for 92.16% of the effective key topics. To a large extent, these 28 high-frequency key themes reflect the status quo of China’s sustainable development policies on rural education (See Table 2).

Table 2.

High-frequency key topics.

3. Results

General understanding of China’s sustainable development policy relating to rural education.

Educators and teachers in rural areas demonstrated an average understanding (an average score of 3.73) of the sustainable development policy on rural education. Scores for satisfaction levels relating to policy design, content, and implementation were average at 3.34, 3.04, and 3.14, respectively. The degree of satisfaction with policy implementation was the lowest, with a score of just 2.99. Senior school administrators and title holders, those within an age range of 41–50 years, and respondents with a junior college education or below demonstrated a better understanding of sustainable development policies relating to rural education, but scores for other dimensions were below 4, except for those of senior school administrators, who demonstrated a good level of understanding. All the dimensions related to satisfaction with policy design were at an average level, with scores ranging between 3 and 4, except for those with doctoral degrees, whose average satisfaction score was below 3. Educational administrators, intermediate job holders, individuals in the age range of 31–40 years, and master’s and doctoral degree holders all scored less than 3 points for satisfaction with policy content, demonstrating a low level of satisfaction, while scores for other dimensions were average. The scores of teaching and research staff and master’s and doctoral degree holders for satisfaction with policy implementation were all below 3 points, indicating a low level of satisfaction, while scores for other dimensions were average. Education administrators, teachers, teaching and research staff, middle-level professionals, respondents in the age range 31–40 years, and those with bachelor’s degrees or above all scored less than 3 points for satisfaction with policy implementation, indicating a low level of satisfaction, while scores for other dimensions were average (see Table 3 for details).

Table 3.

General cognition of sustainable development policy of Rural education in China.

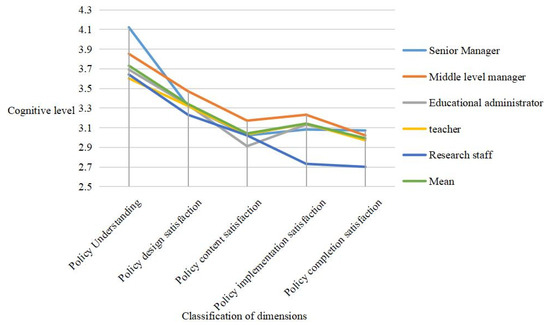

Considering the dimension of position, the degree of understanding of the policy was good (the highest) among senior school managers, whereas respondents with other positions demonstrated an average level of understanding, with the degree of understanding of the teachers being the lowest. Not all the educators and frontline teachers were satisfied with the policy design, which was at an average level. However, middle managers were relatively satisfied with the policy design. Educational administrators demonstrated the lowest (poor) degree of satisfaction with the policy content, while the degree of satisfaction of other educational workers and teachers was average. The degree of satisfaction with policy implementation was lowest (weak) among teaching and research staff, with the satisfaction level among the remaining educational workers and teachers being average. Whereas satisfaction levels relating to policy implementation were average among senior and middle school managers, those of the remaining educational workers and frontline teachers were very low (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Policy cognition of different positions on sustainable development of rural education in China.

For the dimension of professional titles, the degree of understanding of those with senior titles was the highest but was still not strong, remaining at an average level. The degree of understanding of the policy among respondents with junior and intermediate titles was average, whereas those with junior titles had the lowest degree of understanding of the policy. All the educators and teachers demonstrated low satisfaction levels relating to the policy design, which were at an average level. The satisfaction level of intermediate teachers regarding the policy design was relatively low. Those with intermediate positions evidenced the lowest degree of satisfaction with policy content, which was weak, whereas the remaining educational workers and frontline teachers demonstrated an average degree of satisfaction with policy content. All the educators and frontline teachers had low scores for satisfaction with the policy design, which were at an average level. Intermediate and senior teachers have relatively low satisfaction scores for policy implementation. Those with intermediate positions demonstrated the lowest (weak) satisfaction levels with policy implementation, whereas the remaining educational workers and frontline teachers demonstrated an average level of satisfaction with policy content (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cognition of Chinese rural education sustainable development policy by different title holders.

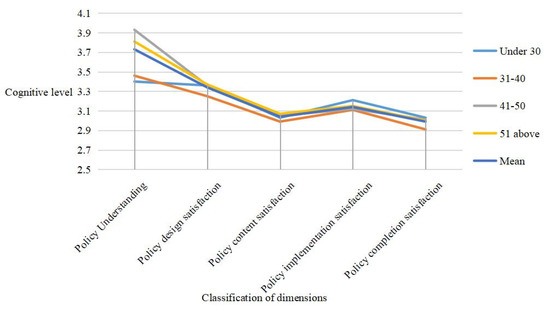

Among different age groups, those aged 41–50 years had the highest level of policy understanding, which approximated a good level, followed by respondents aged 51 years and above. Those aged 30 years and below had the lowest level of policy understanding, and individuals aged 31–40 years had the lowest (poor) level of satisfaction with policy content. Other educational workers and frontline teachers demonstrated an average level of satisfaction with the policy content, with a small gap. Not all of the educational workers and frontline teachers were satisfied with the implementation of the policy, which was at an average level with a small gap. Those aged 31–40 years demonstrated the lowest degree of satisfaction with the implementation of the policy, which was at a poor level, whereas other educational workers and frontline teachers demonstrated an average degree of satisfaction with the policy’s implementation with a small gap (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The cognition of different age groups on the policy of sustainable development of Rural education in China.

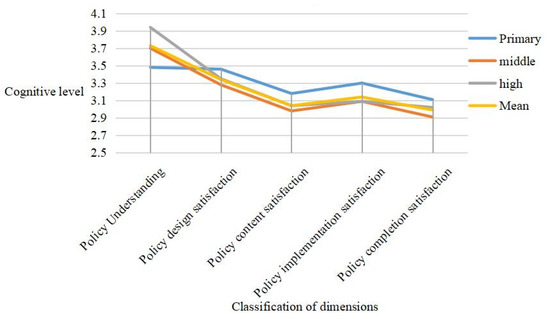

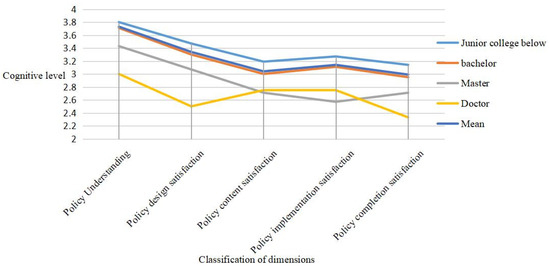

Among the educators and frontline teachers, those with an educational background of junior college or below had a relatively good understanding of the policy. Educational administrators demonstrated the lowest degree of satisfaction with the content of the policy, which was poor, whereas other educational workers and frontline teachers demonstrated an average degree of satisfaction with the content of the policy. The level of satisfaction with the content and implementation of the policy was lowest (poor) among doctoral and master’s degree holders, whereas other educators and frontline teachers had an average degree of satisfaction with the content and implementation of the policy. Apart from respondents with an educational background of junior college or below, respondents’ satisfaction levels relating to the policy’s implementation were at a low level (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Cognition of Chinese rural education sustainable development policy among people with different educational backgrounds.

3.1. Cognitive Differences in Demographic Variables of Sustainable Education Policy in Rural China

We performed a one-way multivariate ANOVA, considering the posts held by rural educators and frontline teachers as well as their professional titles, ages, and educational backgrounds as independent variables. Levels of satisfaction regarding the policy design, content, and implementation were taken as the dependent variables. Our results indicated that there were no significant differences in satisfaction relating to policy design, content, and implementation among rural educators and frontline teachers whose positions, professional titles, ages, and educational backgrounds differed. These results indicate a consensus of opinions among rural educators and frontline teachers relating to China’s policy on sustainable development of rural education (see Table 4).

Table 4.

One-way ANOVA of policy satisfaction based on demographic variables.

3.2. Cluster Analysis of Issues Relating to the Policy of Sustainable Development of Rural Education in China

The core issue was not predetermined; rather, it was formulated through the processes of textual content analysis and induction. First, 12 core themes were obtained through second-order coding on the basis of the high-frequency key themes (derived from first-order coding), as shown in Table 5. Next, we conducted a semantic interpretation of the core themes and identified four dimensions within the cluster unit of “policy”: policy design, content, and implementation.

Table 5.

Clustering of key themes on policy issues of sustainable development of Rural education in China.

4. Discussion

The findings of our literature review and policy text and data analyses revealed that although the policy of sustainable development of rural education implemented in China has made remarkable strides from a historical perspective, many problems remain. There was a consensus of opinions and satisfaction levels relating to the policy, with no significant differences. The satisfaction levels of respondents relating to the design, content, and implementation of the policy were average, with the degree of satisfaction with policy implementation being the lowest and rated as poor. Key findings of the study are outlined below.

4.1. An Unreasonable Policy Design: Rural-Based Care Is Not Enough

Since the initiation of China’s reform and opening-up process, rural education has played an increasingly important role in the national strategy, and its strategic positioning for priority development has been clearly defined. However, the problem of insufficient consideration of a rural orientation has remained prominent during the process of designing a rural education policy. Importantly, the actual status of rural education is not reflected in the policy design. One frontline teacher pointed out that “under the current policy background, rural education seems to be attached to urban education, and there is still a great imbalance between urban and rural education resources”. Keywords, such as “support”, “compensation”, and “balance” occur frequently in the text of the policy document, implying value-based assumptions and judgments of “strong cities” and “weak villages”. The design of the policy focuses mainly on the support of rural education through the extension of urban educational resources, for example, through urban and rural rotation plans for principals and teachers and matching support between the East and West. The intention of these policies is to improve the skills of teaching staff and the operational procedures of rural schools. However, rather than fostering the sustainable development of rural education, this approach, which can be viewed as being analogous to a blood transfusion, may end up reinforcing a weak position of passive acceptance of rural education. Second, actual rural care is inadequate. According to the results of our survey, only 10% of rural educators and teachers felt that rural education policies closely or adequately meet the needs of rural areas, with nearly half of the respondents (46.9%) believing rural education policies do not closely or adequately meet the needs of rural areas. The aim of the policy is to optimize educational resources. However, in practice, the policy does not reflect full consideration of the special case of rural China and is the result of top-down administrative promotion of junior high, from birth, which will face enormous controversy.

Since the central Chinese government issued the “Decision on the Reform and Development of Basic Education” in 2001 and formally proposed to “merge schools”, the number of rural primary schools across the country has dropped by 65% from 440,000 to 155,000, which has negatively affected primary school enrollment rates. Moreover, rural education policies do not sufficiently reflect rural characteristics. According to the results of our survey, only 16.8% of rural educators and frontline teachers thought that rural education policies reflect rural characteristics, with 39.4% believing the policies do not reflect rural characteristics or hardly do so. Rural society and culture have unique characteristics that are not adequately incorporated into the current educational policy design. One school administrator pointed out that “rural education policy pertinence is not strong, and the characteristics of rural society are not obvious [in the policy]”. The focus has been on the construction of the “infrastructure” of rural education and on teams of rural teachers, with less attention given to the construction of the sociocultural dimensions of rural education. In other words, the concept of comprehensive rural revitalization is still not fully reflected in rural education policies, with attention directed at the “educational” aspects of rural education and little consideration given to aspects of “rurality”. Consequently, local elements are missing.

4.2. Imperfect Policy Content: Integration and Symbiosis Are Still Lacking

Although the quality of rural education has improved significantly since the initiation of China’s reform and opening up process, there are still deficiencies relating to the integration of urban and rural areas, family education, and the symbiosis of the three types of education. First, urban and rural development remain to be fully integrated. According to the results of our survey, only 23.9% of rural education workers and frontline teachers believed that rural education policies reflect the integrated development of urban and rural areas, with 34.8% opining that the policies poorly reflect integrated development of urban and rural areas or not at all. Within the current rural education policy, the focus is on the balanced development of urban and rural education; education reflects a mostly unidirectional flow from urban to rural education. Consequently, rural education does not have a clearly defined position and role within the overall education system, which does not reflect its role. Thus, the two-way interaction and integration of urban and rural education development remains to be achieved.

A second gap relates to rural family education. According to the results of the survey, 37.2% of rural education workers and frontline teachers felt that rural education policies pay more or a lot of attention to family education, 35.3% felt that rural education policies pay more or a lot of attention to family education, and 27.5% felt that rural education policies pay less or a little attention to family education. Family education is an important component of rural education and is an essential resource for students. However, rural family capital is relatively weak, and there is a tendency for rural parents to be absent. The respondents highlighted the problem of left-behind children. For example, one frontline teacher pointed out the gravity of the problem, noting that “half of the students in our class have parents who are working away and rarely return home, they lack family education”. Currently, rural education policies focus on school education, while neglecting family education. There is a dearth of policy support for rural family education and a lack of attention to organizational development, the provision of necessary resources, the development of a service mechanism, and other requirements. A third issue relates to the lack of clarity regarding the “coexistence of the three religions”. According to the survey results, 31.2% of rural educators and frontline teachers felt that rural education policies focus on the “coexistence of education, education and education”, whereas 40.7% felt that they paid little or only limited attention, and 28.1% felt that they pay little or only limited attention. Sole reliance on school education is not sufficient for developing talents in rural areas required to construct an industrial culture, safeguard ecologies, and revitalize organizations. Comprehensive revitalization of rural education not only entails the revitalization of education within rural schools and a focus on rural students; it also requires the revitalization of adult farmers, rural areas, and rural practitioners. Thus, the co-development of school education, family education, and community education is essential for the comprehensive revitalization of rural education. Currently, there is still insufficient attention paid to family education and social education within rural education policies, and the organizational structure, mechanism, and respective responsibilities and obligations entailed the development and balancing of the three types of education remain to be clarified.

4.3. Poor Policy Implementation: Continuing Gaps in the Governance System

The effective implementation of rural education policies requires a strong governance system for the management of rural education. Since the initiation of the reform and opening-up process, rural education policies for enabling reforms of the management systems and mechanisms of rural education have received focused attention, and the governance system has been continually improved. However, some outstanding problems remain to be resolved. The survey results showed that 82.7% of rural educators and frontline teachers thought that the implementation of rural education policies was average, poor, or very poor. The first point to consider is that there is just one primary governance body. Of the respondents, 30.8% of rural education workers and frontline teachers reported minimal or no participation in governance relating to rural education. Rural revitalization is not only an aspect of rural revitalization, and rural education is not confined to rural school education; rather, rural education encompasses the relevant government departments, schools, communities, social organizations, teachers, students and parents, and other subjects. Currently, the implementation of rural education policies is mostly government-led, comprising “top-down” administrative interventions.

Second, the level of coordination among departments is weak. According to the survey results, only 14.3% of rural education workers and frontline teachers considered the level of coordination among different departments in the implementation of the rural education policy to be good or very good, with 51.5% considering it to be average, and 37.1% viewing it as poor or very poor. To promote rural revitalization, more government departments need to be involved in the management of rural education management compared with those presently involved. Moreover, collaborations among administrative departments remain inadequate despite the establishment of a revitalization bureau tasked with planning China’s revitalization at a national level. However, achieving the sustainable development of rural education will require the administrative strengthening of the education department and of other relevant departments. One rural education administrator made the following point: “There are many difficulties in cross-departmental collaborative work, and some policies are difficult to implement effectively and efficiently”. A third issue relates to a flawed governance mechanism. According to the survey results, only 20% of rural education workers and frontline teachers consider the governance mechanism relating to rural education to be sound or very sound, with 46.3% considering it to be average and 33.7% viewing it as flawed or not very sound. There is a lack of effective governance mechanisms, notably those associated with organizational coordination, communication, social participation, and supervision, for example, of left-behind children within the management structure of rural education. Consequently, there is no clear delineation of responsibilities and job requirements within organizational structures so that the relevant social forces to participate in the project diversification end up as wasted resources.

4.4. Inadequate Policy Implementation: Insufficient Support of Teacher Resources

Teacher resources are critical for the sustainable development of rural education. Commencing from the beginning of this century, China’s policies on rural teachers have evidenced a gradual trend of becoming increasingly systematic and comprehensive, effectively alleviating the problems of ineffective teaching and the failure to retain rural teachers. However, there is still a paucity of high-quality teachers. Thus, in 2019, there was a significant gap between urban and rural preschool education teachers. The proportion of senior principals and full-time teachers with postgraduate degrees employed at urban kindergartens was considerably higher than the average number of such individuals working at kindergartens in towns, villages, and across the entire country.

There have also been some problems in the implementation of the policy on rural teachers. First, despite their traditional role as models and as a leading force of social governance within traditional rural society, rural teachers are accorded a marginalized status. Currently they are marginalized within the process of rural revitalization.

Second, the remuneration of rural teachers is low and needs to be improved. According to the results of our survey, 16.1% of rural educators and frontline teachers believed that efforts to improve the status of rural teachers have not achieved the expected outcome or that they have been far from adequate. At present, the treatment of rural teachers remains poor, and the relevant policies on rural teachers’ salary standards and living subsidies are not sufficiently strong and lack binding force. Moreover, the demarcation range of policy target groups and subsidy standards are not sufficiently detailed. There is no clear preferential policy prioritizing rural teachers and no corresponding social welfare system.

Third, there is inadequate support for the professional development of rural teachers. The findings of the survey indicated that currently there are 35.6% of rural education workers, and many teachers feel that rural teachers’ professional development support is neither good or bad. The implementation of a training policy for rural teachers has not achieved its targets and expected impacts, with rural teacher training remaining inadequate. Thus, the lack of high-quality training of teachers in rural education remains a serious concern. In addition, standards for evaluating rural teachers’ titles need to be refined, and an appropriate evaluation index system for promoting rural teachers’ professional development needs to be established.

5. Conclusions and Remarks

Adhering to a rural orientation: The concept of rural-oriented development has gradually been strengthened through policy implementation, leading to the consolidation of the priority status of rural education and the promotion of rural education aligned to sustainable development. Therefore, the policy design should be aimed at strengthening a rural orientation by applying the following approaches. The first is to ensure the equal status of rural and urban education. This construction of rural education requires tackling inherent biases in the policy design relating to rural education. Specifically, there is a need to shift from a view of rural education grounded in a “country standard” and “country revitalization” whereby the mode of urban education provides the basis for developing rural education. Moreover, a shift from a passive approach to rural education to one that emphasizes endogenous development of rural education is required. It is also necessary to strengthen the particularity of rural education field care. The special situation of rural education, determined through in-depth research in rural areas should be incorporated in the policy design. The urban mode of education should not be blindly pursued; rather, practical, targeted rural education policies that are based on actual rural contexts should be developed. Lastly, there is a need to introduce the concept of localization into the process of developing rural education. Implementation and associated sustenance of education is needed to transform the modernization of rural education into a viable path in policy design. Rural human and natural environments need to be incorporated into and firmly established within the development philosophy of rural education for standardizing and implementing national education reforms and initiating efforts to support the country’s revitalization, while also strengthening local cultures. All of these activities can contribute to promoting the sustainable development of rural education.

Improving the integration and symbiosis of policy content: Considering China’s rural revitalization strategy, urban and rural development are gradually moving toward integration and symbiosis. The extension of integration and symbiosis to rural education policies should also gradually lead to improvements in their content. It is important to construct a system of urban and rural education resources that reflects their integration and symbiosis. This requires the pursuit of policy equality and improved policies for achieving integrated urban and rural development. An “equality” consciousness should permeate the content of rural education policies, covering all aspects from balanced fairness to integrated equality to ensure the equality of urban and rural education. Further efforts to promote two-way interactions of urban and rural education resources, reshape the cultural confidence of rural education, build a system and mechanism for fostering the integrated development of urban and rural education, improve the policy content, and provide policy support for the integrated development of urban and rural education are required. Improving rural family education policies also requires attention. The family is the basic unit of rural education, transmitting the moral quality of family culture across generations, and family education is the foundation and “soft power” driving rural education. There is a need to improve policies for supporting family education that encourage the cultivation of sound family traditions in the new era, while continuing to focus on the issue of left-behind children and formulate policies to promote organizational development, resource provision, and the design of service mechanisms. A third requirement is the coordinated development and improvement of the policy of co-existence of the three types of education. In the context of rural revitalization, the sustainable development of rural education necessarily entails the symbiotic development of school education, family education, and community education so that these three types of education as well as rural family education and community education policies assume complementary positions and functions with the rural education system. In addition, supportive measures and an appropriate organizational mechanism will be required to strengthen the co-development of the three education sectors.

Building the ranks of rural teachers. Teachers play a key role in the sustainable development of rural education and in the overall process of rural revitalization. Therefore, the following issues relating to rural teachers require attention. First, continuing and comprehensive efforts should be made to improve the status and treatment of rural teachers. The salaries of frontline teachers and head teachers should be raised, and they should be provided with benefits to incentivize them to perform well. A system of differentiated allowances and subsidies for rural teachers should be introduced, and improvements should be made in existing systems of rewards, social security, and honoring teachers. The social status of teachers should be improved, and communication channels enabling rural teachers to participate in rural affairs should be opened up. Reasonable preferential social treatment of rural teachers should also be introduced. Comprehensive reforms of rural teacher education should be continued.

An integrated approach to teachers’ pre- and post-service training and the curriculum content for rural teachers’ education should be introduced. County (district) level rural teacher development centers should be established, and public funding of local students should be continued. Rural teacher training and master of rural school education teacher training should be introduced to encourage rural teachers to promote education. The continued development and implementation of plans to improve the information literacy of rural teachers (and principals) and to promote their all-round professional development is also necessary.

Rich experience has accumulated because of policy shifts to promote the sustainable development of rural education in China, and considerable progress has been made in this area. However, formidable challenges remain, requiring developmental interventions. We conducted a literature review in conjunction with policy and empirical research, aimed at comprehensively analyzing experiences and problems relating to China’s policy on the sustainable development of rural education and proposed recommendations for its improvement and optimization. The study had some limitations. First, while we conducted a literature review as well as policy analysis and empirical research, we were unable to implement a large-scale experiment on rural education because of time and research constraints. Second, we conducted an analysis of rural education policies that focused on the macro level but did not pay sufficient attention to the meso and micro levels. Because of spatial and research limitations, we devoted limited attention to schools, curricula, and teaching research in the field of rural education. Future studies should attend to the following aspects. They should enrich and expand their research methods by including a large-scale rural education construction experiment, combining theoretical and empirical research. The research scope should also be expanded, combining the macro, meso, and micro scales and including a consideration of rural schools, curricula, and teaching research. The conclusions of this study also require verification by exploring and testing their practical application, followed by iterative revision.

In conclusion, this study analyzed China’s policies in the field of education, and it has shown that rural education has undergone several stages since the initiation of the reform and opening-up process in China: a recovery stage following adjustments, comprehensive reform, and an emphasis on overall development and revitalization. Adhere to the unified leadership of the party as a fundamental, according to the guideline of the reform of comprehensive, rural construction to serve as the goal, to promote education fair as the main line, teacher team construction as the key policy experience, etc. The findings of our empirical research revealed that the policy of sustainable development of rural education in China is unsatisfactory, and there are outstanding problems in policy design, content, and implementation, such as insufficient rural-based care, a lack of integration and synthesis and of an effective governance structure, and insufficient support for teachers. Considering our textual and empirical analyses, we recommend optimizing the following aspects of the policy on the sustainable development of rural education in China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.X. and J.L.; methodology, E.X. and J.L. software, E.X., J.L. and X.L.; validation J.L. and X.L.; formal analysis, E.X., J.L. and X.L.; investigation, E.X., J.L. and X.L.; resources, E.X. and J.L.; data curation, J.L. and X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.X., J.L. and X.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and E.X.; visualization, J.L. and X.L.; supervision, E.X.; project administration, E.X.; funding acquisition, E.X. E.X. and J.L. share the co-first authorship; J.L. and X.L. share the co-corresponding authorship in this study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Beijing Education and Science Priority Research Project: Coordinated Development of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and Optimal Allocation of Vocational Education Resources in Beijing (Project Number: AEAA17010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Shi, Z.; Xue, E. The problems, needs and strategies of rural teacher development at deep poverty areas in China: Rural schooling stakeholder perspectives. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 99, 101496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Xu, L. Government responsibility in the development of rural school bus—Based on the layout adjustment of compulsory education schools. J. Educ. China 2011, 20, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.; Wang, S. The impact of education public goods allocation adjustment on human capital: A study based on school merger. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 5, 138–154. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Li, L. Values, difficulties and suggestions of social forces in rural education governance. J. Southwest Univ. 2019, 20, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. The process of rural development and the path of rural revitalization in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 20, 1408–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Jiang, J. Thoughts on the strategy of rural revitalization serving education. J. Wuhan Univ. 2021, 20, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Wang, J. Historical context and modern enlightenment of rural education development in China. J. Southwest Univ. 2017, 20, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Compulsory educational policies in rural China since 1978: A macro perspective. Beijing Int. Rev. Educ. 2020, 2, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J. Improving teacher development in rural China: A case of “rural teacher support plan”. Beijing Int. Rev. Educ. 2020, 2, 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, Y. Empowerment approach to include women in rural development and motivate adolescent girls through education job training: Successful NGO’s activities. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2012, 10, 128–140. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Yang, X. Rural revitalization: Rural education as strategic support and its development path. J. South China Norm. Univ. 2018, 20, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J. Research on action logic and path of promoting educational equity in urban and rural areas from the perspective of targeting poverty alleviation. Educ. Econ. 2018, 201, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Tang, W. Research on the optimization strategy of rural teachers’ policy targeting. J. Natl. Inst. Educ. Adm. 2020, 20, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, B.; Yi, W. The role and status of non-governmental (‘daike’) teachers in China’s rural education. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2008, 28, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Tian, X. Development and innovation of rural teacher team construction policies in China. Educ. Res. 2018, 20, 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, P. The logical purpose of rural school principal’s leadership in localization education. Educ. Res. 2020, 20, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Li, Y. On the revitalization of rural education—Based on the theory of the co-existence of urban and rural education resources. Educ. Res. 2020, 20, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, S.; Walker, L.; Farthing, A.; Brown, L.; Moran, M. Understanding the elements of a quality rural/remote interprofessional education activity: A rough guide. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2021, 29, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J. Unequal education, poverty and low growth—A theoretical framework for rural education of China. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2008, 27, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anlimachie, M.A.; Avoada, C. Socio-economic impact of closing the rural-urban gap in pre-tertiary education in Ghana: Context and strategies. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2020, 77, 102236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, A. Moving mountains stone by stone: Reforming rural education in China. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2009, 29, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bor, W.; Holen, P.; Wals, A.; Filho, W.L. (Eds.) Integrating Concepts of Sustainability in Education for Agriculture and Rural Development; Peter Lang Publishing: Bern, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Hu, N. Realistic dilemma and path choice of rural education revitalization in the new era. J. Southwest Univ. 2019, 20, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, E.; Liu, M. New achievements, challenges and trends in the development of educational equity in China. Educ. Res. Tsinghua Univ. 2018, 20, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z. On the role of rural teachers as new villagers in rural revitalization strategy. Educ. Res. 2020, 20, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).