Social Entrepreneurs as Role Models for Innovative Professional Career Developments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Previous Relevant Literature

2.1. Social Entrepreneurs

2.2. The Decision-Making Process in Social Entrepreneurships

3. Materials and Methods

- What is the most important value in your life, personal as well as professional?

- How has this value been present throughout your life?

- Any example or specific situation showing the importance of this value?

- How is this value reflected in your social enterprise?

- Why did you create this specific enterprise?

- How did you create it?

- How is your company now?

- How do you visualize it in the future?

- What problem is your company trying to solve?

- Why did you focus on this specific problem?

- How do you understand this problem and its possible solution?

- Do you have professional career development with a purpose?

- If so, what is your purpose?

- What is your personal definition of success?

4. Results

You also must be lucky. I anticipated the issue of edible straws, but, at the same time, we have arrived at a good moment with all the awareness regarding the problem of plastic. (Case 5)

4.1. Group 1: Motivation Factors

It made me empathize with her problem, seeing that, in addition, it was relatively easy to solve and not much was being done. Her pain hurt me, that they could laugh at her, and she couldn’t live a normal life. (Case 3)

My purpose is to transcend, be helpful to improve things, go beyond my own limits. From there, I´m aware that my happiness consists of generating happiness for others, that I´m not the most important, but what happens through me. (Case 6)

The key value we pursue is that of social equality, democratizing access to science in very vulnerable environments. In poor neighborhoods, children don’t have any exposure to science for interest in it to emerge. (Case 2)

Hugo, my partner, had six stores distributed in six towns in the province of Soria, and, in June 2013, with the crisis, there came a time when we had to close them. (Case 8)

The problem is twofold, on the one hand, a huge rate of youth unemployment, around 50%, and on the other, the shortage of scientific callings. (Case 2)

4.2. Group 2: Personal Resources

At that time, we did not know the entire ecosystem that exists around the entrepreneurial world and start-ups. We discovered that we were a start-up with an idea and that we needed investors to make that idea a commercial reality. There, we realized the difficulty of presenting and explaining a project, and we got a lot of negatives. But, in the end, we learned. (Case 7)

We started 4 years ago, having a few beers with two friends, one of them already working in a social enterprise, and we decided to combine social enterprise and water. We went to see a friend of my father who was dedicated to the valuation of companies. It helped us to know what a business plan was. (Case 4)

Persistence is also key, insisting and insisting, over and over again. Many investors have valued that we presented the project several times after successive refusals. According to them, with this, we demonstrate the ability to learn, correct, and apply the improvements that they suggested, and that is very good. (Case 7)

Within this digital world, we are getting them to trust us for their basic and essential purchases. We have already overcome one difficulty, that of the need to “touch” the product, and they believe in us. We are putting together basic, natural, and traditional products with digital technology; what is local, rural, and ecological, with what is global. (Case 1)

I believe that it is essential to make social good and, at the same time, manage efficiently and professionally. It is necessary to generate economic profits so that social development can be funded. (Case 6)

4.3. Group 3: Facilitating Factors

Initially, we raised 100,000 euros through a crowd-funding system. We had 36 participating partners. We also opted for a mentorship program, which gave us visibility and more funding partners. In the next round, we raised another 250,000 euros from 40 more participating partners. (Case 1)

In Peru, the people I knew didn’t ask themselves these kinds of questions; they couldn’t afford that luxury, they couldn’t get depressed; their struggle was to survive each day. (Case 4)

I got the Hong Kong scholarship first. Then, I got another scholarship to study molecular biology at Princeton. Later, I entered the CNIO (National Center for Oncological Research), also with a scholarship system. From there, I decided to do my doctorate with good publications. I was awarded the doctorate with an extraordinary prize. Everything indicated that if I continued, I would get a post-doctorate in a cool place. (Case 2)

I started in this five years ago as a brand ambassador. I was a salesman, with grace, to promote the brand that was paying me. I wanted to sell the product, the gin, in another way, with a different touch. (Case 5)

These people have taught me that sometimes I must make decisions with my heart. I have discovered that there is a key role for personal relationships, that decisions are not always analytical and rational. (Case 3)

Before, I had worked 10 years in an international NPO. I was passionate about that job. (Case 8)

“La Exclusiva” is mine and Hugo’s, something that we created. It is our life project. I have learned more than ever; I really enjoy it. Also, I have met people along the way who work just like me to achieve their goals. It is exciting; I have a great time. (Case 8)

I had always thought that I wanted to do something big, something that would impact the world, like winning a Nobel Prize. (Case 3)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dacin, P.A.; Dacin, M.T.; Matear, M. Social Entrepreneurship: Why We Don’t Need a New Theory and How We Move Forward From Here. Acad. Manag. 2017, 24, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez de Mon, I.; Gabaldón, P.; Nuñez-Canal, M. Social entrepreneurs: Making sense of tensions through the application of alternative strategies of hybrid organizations. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei-Skillern, J. Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Rev. Adm. 2012, 47, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelos, C.; Mair, J. Social entrepreneurship: Creating new business models to serve the poor. Bus. Horiz. 2005, 48, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L. The Rhythm of Leading Change: Living With Paradox. J. Manag. Inq. 2012, 21, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Toward a Theory of Paradox: A Dynamic equilibrium Model of Organizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanos-Contreras, O.; Jabri, M.; Sharma, P. Temporality and the role of shocks in explaining changes in socioemotional wealth and entrepreneurial orientation of small and medium family enterprises. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1269–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawhouser, H.; Cummings, M.; Newbert, S.L. Social Impact Measurement: Current Approaches and Future Directions for Social Entrepreneurship Research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 43, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Martí, A.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Palacios-Marqués, D. A bibliometric analysis of social entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1651–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Gedajlovic, E.; Neubaum, D.O.; Shulman, J.M. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-L.; Williams, J.; Tan, T.-M. Defining the ‘Social’ in ‘Social Entrepreneurship’: Altruism and Entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 1, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agafonow, A. Toward A Positive Theory of Social Entrepreneurship. On Maximizing Versus Satisficing Value Capture. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Besharov, M.L.; Wessels, A.K.; Chertok, M. A Paradoxical Leadership Model for Social Entrepreneurs: Challenges, Leadership Skills, and Pedagogical Tools for Managing Social and Commercial Demands. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seanor, P.; Bull, M.; Baines, S.; Ridley-Duff, R. Narratives of transition from social to enterprise: You can’t get there from here! Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2013, 19, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, S.; Mickiewicz, T.; Stephan, U. Human capital in social and commercial entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 4, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 1, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschee, J. Social entrepreneurs. Across Board 1995, 32, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Alvord, S.H.; Brown, L.D.; Letts, C.W. Social Entrepreneurship and Societal Transformation: An Exploratory Study. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2016, 40, 260–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verreynne, M.-L.; Miles, M.P.; Harris, C. A short note on entrepreneurship as method: A social enterprise perspective. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2012, 9, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.; Majumdar, S. Social entrepreneurship as an essentially contested concept: Opening a new avenue for systematic future research. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Jiang, S.; Hu, S. Social entrepreneurs’ personal network, resource bricolage and relation strength. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 2774–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.X.; Liu, C.F.; Yain, Y.S. Social Entrepreneur’s Psychological Capital, Political Skills, Social Networks and New Venture Performance. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundström, A.; Zhou, C. Rethinking Social Entrepreneurship and Social Enterprises: A Three-Dimensional Perspective. Soc. Entrep. 2014, 29, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, L.A.; Zhang, D.D. The social entrepreneurship zone. J. Nonprofit Public Sector Mark. 2010, 22, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froelich, K.A. Diversification of revenue strategies: Evolving resource dependence in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 1999, 28, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource Dependence Theory: A Review. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, S.; Butt, M.; Ashfaq, F.; Maran, D.A. Drivers for Non-Profits’ Success: Volunteer Engagement and Financial Sustainability Practices through the Resource Dependence Theory. Economies 2020, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, X. Performance Management System in a Non-profit Local Governmental Broadcaster. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2013, 5, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Helmig, B.; Ingerfurth, S.; Pinz, A. Success and Failure of Nonprofit Organizations: Theoretical Foundations, Empirical Evidence, and Future Research. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2013, 25, 1509–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.; Szkudlarek, B.; Seymour, R.G. Social impact measurement in social enterprises: An interdependence perspective. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2015, 32, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei-Skillern, J. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.R.; Stevens, C.E. Different types of social entrepreneurship: The role of geography and embeddedness on the measurement and scaling of social value. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 575–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L.; Tornikoski, E.T. Resource acquisition in the emergence phase: Considering the effects of embeddedness and resource dependence. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 249–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, P.; Pazzaglia, F.; Sonpar, K. Large-Scale Events as Catalysts for Creating Mutual Dependence Between Social Ventures and Resource Providers. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 470–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, A.; Venkatraman, N. Relational governance as an interorganizational strategy: An empirical test of the role of trust in economic exchange. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-W.; Fu, L.-W.; Wang, K.; Tsai, S.-B.; Su, C.-H. The Influence of Entrepreneurship and Social Networks on Economic Growth—From a Sustainable Innovation Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; Moss, T.W.; Lumpkin, G.T. Research in social entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future opportunities. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2009, 3, 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, B. Against the Cult(ure) of the Entrepreneur for the Nonprofit Sector. Adm. Theory Prax. 2016, 38, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargadon, A.B.; Douglas, Y. When Innovations Meet Institutions: Edison and the Design of the Electric Light. Adm. Sci. Q. 2016, 46, 476–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, M.K. Organizational Innovation and Substandard Performance: When is Necessity the Mother of Innovation? Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Nelson, R.E. Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundry, L.K.; Kickul, J.R.; Griffiths, M.D.; Bacq, S.C. Creating Social Change Out of Nothing: The Role of Entrepreneurial Bricolage in Social Entrepreneurs’ Catalytic Innovations. In Social and Sustainable Entrepreneurship; Lumpkin, G.T., Katz, J.A., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; Volume 13, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Ofstein, L.F.; Kickul, J.R.; Gundry, L.K. Bricolage in Social Entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2015, 16, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilber, T.B. Stories and the Discursive Dynamics of Institutional Entrepreneurship: The Case of Israeli High-tech after the Bubble. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, C.; Howorth, C. The language of social entrepreneurs. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2008, 3, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeilstetter, R.; Gómez-Carrasco, I. Local meanings of social enterprise. A historical-particularist view on hybridity of organizations. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2020, 134, e69162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Leca, B.; Boxenbaum, E. How Actors Change Institutions: Towards a Theory of Institutional Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 65–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Entrepreneurship for social impact: Encouraging market access in rural Bangladesh. Corporate Governance: Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, H.; Katz, H. Social entrepreneurs narrating their careers: A psychodynamic-existential perspective. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2016, 25, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, Y.; Shang, L. Unpacking the biographical antecedents of the emergence of social enterprises: A narrative perspective. VOLUNTAS: Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2017, 28, 2498–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asarkaya, C.; Taysir, N.K. Founder’s background as a catalyst for social entrepreneurship. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2019, 30, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruskin, J.; Seymour, R.G.; Webster, C.M. Why Create Value for Others? An Exploration of Social Entrepreneurial Motives. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 1015–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K. Determinants of Social Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyoike, C.N.; Maseno, M. Exploring the motivation of social entrepreneurs in creating successful social enterprises in East Africa. N. Engl. J. Entrep. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandyoli, B.; Iwu, C.G. Determining The Nexus Between Social Entrepreneurship and the Employability of Graduates. Socioecon. Naučni Časopis Teoriju Praksu Društveno-Ekon. Razvoja 2016, 5, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, A.; Gilbert, D.H. Enhancing graduate employability through work-based learning in social entrepreneurship: A case study. Educ. + Train. 2013, 55, 550–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H. A conceptual model for social entrepreneurship directed toward social impact on society. Soc. Enterp. J. 2011, 7, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Alvy, G.; Lees, A. Social entrepreneurship—A new look at the people and the potential. Manag. Decis. 2000, 38, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guclu, A.; Dees, J.G.; Anderson, B.B. The Process of Social Entrepreneurship: Creating Opportunities Worthy of Serious Pursuit; Fuqua Shool of Business: Durham, NC, USA, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Simms, S.V.K.; Robinson, J. Activist or Entrepreneur? An Identity-based Model of Social Entrepreneurship. Int. Perspect. Soc. Entrep. Res. 2009, 9–26. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253737397_Activist_or_entrepreneur_an_identity-based_model_of_social_entrepreneurship (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 27, p. 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Becker, G. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, P.; Honig, B. The role of social and human capital among nascent enrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventiruing 2003, 18, 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danna, D.; Porche, D. Establishing a Nonprofit Organization: A Venture of Social Entrepreneurship. J. Nurse Pract. 2008, 4, 751–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G. The Meaning of “Social Entrepreneurship.” Duke Faqua 2001, 1–5. Available online: https://centers.fuqua.duke.edu/case/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/03/Article_Dees_MeaningofSocialEntrepreneurship_2001.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Mort, S.G.; Weerawardena, J.; Carnegie, K. Social entrepreneurship: Towards conceptualisation. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2003, 8, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. A Conceptual Model of Entrepreneurship as Firm Behavior. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1991, 16, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field Definition of Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Market Orientation and the Learning Organization. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; He, H. Identification and decision making of social entrepreneurship opportunities based on family social capital and prior knowledge. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Educ. 2020, 57, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes. In The Social Structure of Competition; Havard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Wacquant, L. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, J.G.; Emerson, J.; Economy, P. Strategic Tools for Social Entrepreneurs: Enhancing the Performance of Your Enterprising Nonprofit; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rangan, V.K.; Gregg, T. How Social Entrepreneurs Zig-Zag Their Way to Impact at Scale. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 62, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, J.-E. (Wie); Sloan, M.F. Effectual Processes in Nonprofit Start-Ups and Social Entrepreneurship: An Illustrated Discussion of a Novel Decision-Making Approach. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2015, 45, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S.D. What Makes Entrepreneurs Entrepreneurial? Bus. Soc. Rev. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ladevéze, N.L.; Núñez, M. Noción de emprendimiento para una formación escolar en competencia emprendedora. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2016, 71, 1068–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittz, T.G.; Madden, L.T.; Mayo, D. Catalyzing Social Innovation: Leveraging Compassion and Open Strategy in Social Entrepreneurship. N. Engl. J. Entrep. 2017, 20, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.; Carter, S. Social entrepreneurship: Theoretical antecedents and empirical analysis of entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2007, 14, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.L.; Grimes, M.G.; Mcmullen, J.S.; Vogus, T.J. Venturing for others with heart and head: How compassion encourages social entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 616–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miculaiciuc, A. Social Entrepreneurship: Evolucions, Characteristics, Values and Motivations. Ann. Univ. Oradea Econ. Sci. 2019, 28, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kotlar, J.; De Massis, A. Goal Setting in Family Firms: Goal Diversity, Social Interactions, and Collective Commitment to Family–Centered Goals. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 1263–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Massis, A.; Kotlar, J. The case study method in family business research: Guidelines for qualitative scholarship. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, T.G.; Garry, T. An overview of content analysis. Mark. Rev. 2003, 3, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2016, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, C.; Piekkari, R.; Plakoyiannaki, E.; Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for Int. business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 42, 740–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaskoff, J. Building the Heart and the Mind: An Interview With Leading Social Entrepreneur Sarah Harris. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Bailey, J.M.; Lee, J.; McLean, G.N. “It’s not about me, it’s about us”: A narrative inquiry on living life as a social entrepreneur. Soc. Enterp. J. 2020, 16, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M.B. Crafting Brand Authenticity: The Case of Luxury Wines. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 1003–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Propositions, Classification, and Factors | Literature | |

|---|---|---|

| Motivations | Emotional connection | Emotional antecedents (empathy) [80] |

| Moral judgment | Compassion [81]; Social justice and sense of obligation [53]; Spiritualism [51]; Compassion [79]; Morality [82] | |

| Personal dissatisfaction or need | Emotional antecedents and frustration [80] | |

| Purpose, achievement, change recognition | Prosocial cost–benefit analysis [81]; Altruism, achievement, influence [53]; Altruism [51]; Prosocial benefit [79]; Altruism [82]; Achievement orientation, changing structures and policies [55] | |

| Social and community needs | The entrepreneurial process [80]; Commitment to alleviating suffering [81]; Nurturance [53]; Positive externalities [79]; Closeness to social problem and commitment to helping society, creating social value [55] | |

| Personal resources | Connection skills | Network embeddedness [80]; Integrative thinking [81]; Relatedness [53]; Collectivism [51]; Stakeholder involvement [79]; Relationship with the community, Cooperation [82] |

| Conviction | Persistence [82] | |

| Creativity | Creativity and innovation [80]; Innovation [82] | |

| Efficiency skills | Managing and structuring social enterprise [80]; Autonomy [53] | |

| Learning orientation | Strategic openness [79] | |

| Facilitating factors | Financial and social support | The nature of financial risks and profit [80]; Institutional conditions [81]; Resources [51] |

| Education | Higher education [51] | |

| Past events | Emotional antecedents [53] | |

| Professional experience | Entrepreneurialism, professionalism [51] | |

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of venture | 6 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 6 |

| Sector | Food | Education | Health | Water | Food | Consulting | Health | Logistic |

| Product/Service | Natural food | Science education | Medical software | Water | Straws | Consulting | Medical software | Food retail |

| Target communities | Local community, environmental | Poorer neighborhoods | Unattended health niches | Development, water resources | Environmental | Support for social entrepreneurs | Unattended health niches | Rural communities |

| Number of employees | 15 | 5 | 4 | 20 | 25 | 12 | 5 | 4 |

| Seniority of entrepreneur (age) | 55 | 33 | 31 | 29 | 32 | 52 | 38 | 35 |

| Education (school, graduate, post-graduate) | Graduate | Doctor | Graduate | Graduate | Graduate | Graduate | Graduate | Graduate |

| Experience (business experience, social sector experience, work in sector) | Business and sector | Business, social, and sector | Sector | Social | Sector | Business, social, and sector | Business | Social and sector |

| Observed Factors | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | Total | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivations | Emotional connection | 10 | 11 | 18 | 6 | 13 | 11 | 4 | 9 | 82 | 13% |

| Moral judgement | 6 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 37 | 6% | |

| Personal dissatisfaction or need | 7 | 2 | 15 | 6 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 45 | 7% | |

| Purpose achievement—change recognition | 6 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 56 | 9% | |

| Social and community needs | 4 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 15 | 49 | 8% | |

| Total motivations | 33 | 33 | 53 | 37 | 24 | 41 | 16 | 32 | 269 | 44% | |

| Personal resources | Connection skills | 4 | 4 | 14 | 4 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 51 | 8% |

| Conviction | 4 | 8 | 0 | 7 | 15 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 49 | 8% | |

| Creativity | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 25 | 4% | |

| Efficiency skills | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 15 | 2% | |

| Learning orientation | 8 | 14 | 13 | 10 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 71 | 12% | |

| Total personal resources | 18 | 29 | 35 | 22 | 44 | 15 | 28 | 20 | 211 | 34% | |

| Facilitating factors | Financial and socials | 3 | 9 | 12 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 46 | 8% |

| Higher and social education | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 3% | |

| Past events | 4 | 4 | 18 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 41 | 7% | |

| Professional experience | 5 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 25 | 4% | |

| Total facilitating factors | 14 | 27 | 33 | 14 | 9 | 9 | 13 | 9 | 128 | 21% | |

| Unintended consequences | Total unintended consequences | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1% |

| Total coding references | 65 | 90 | 121 | 73 | 79 | 65 | 58 | 61 | 612 | 100% | |

| Factors | Sample Quotes | Cases | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivations | Emotional connection | These people have taught me that sometimes I must make decisions with my heart. I have discovered that there is a key role for personal relationships, that decisions are not always analytical and rational. | Case 3 |

| Moral judgment | There is less material misery in the world, but spiritual poverty is on the rise. The lack of spirituality leads to not seeing others as persons, and they suffer. Persons are deprived of their true human value because we treat them as objects. | Case 4 | |

| The key value we pursue is social equality, democratizing access to science in very vulnerable environments. In poor neighborhoods, children don’t have any exposure to science at all for interest in it to emerge. | Case 2 | ||

| Personal dissatisfaction or need | I did not last in any of my jobs, restlessly changing from one company to another. Meeting objectives, working under pressure with little care for people was meaningless for me and made me feel alien to myself. | Case 1 | |

| Purpose achievement, change-recognition | I had always thought that I wanted to do something big, something that would impact the world, like winning a Nobel Prize. | Case 3 | |

| Social & community needs | The problem is twofold, on the one hand, a huge rate of youth unemployment, around 50%, and on the other, the shortage of scientific callings. | Case 2 | |

| Personal resources | Connection skills | During a tour in Asia, while we were presenting our project, someone came, very impressed, and offered to put me in touch with someone who wanted to invest in health and the environment, so our investor finally came from Sweden. | Case 5 |

| Conviction | Persistence is also key, insisting and insisting, over and over again. Many investors valued that we presented the project several times. According to them, “if you come one day and I don’t see you again, how do you want me to trust you? Most likely, you have already given up.“ | Case 7 | |

| Creativity | The child, almost blind, could only see shadows. He had the idea of what a star was but had not seen one. That gave us the clue to combine a laser with binoculars to re-create a star. It was “the great moment” for him; he saw a star for the first time. | Case 3 | |

| Efficiency skills | I believe that it is essential to make social good and, at the same time, manage efficiently and professionally. It is necessary to generate economic profits so social development can be funded. | Case 6 | |

| Learning orientation | When we listened to the stories of these people, we found that water played a central role in their miseries, from stomach diseases from drinking contaminated water. | Case 5 | |

| At that time, we did not know the entire ecosystem that exists around the entrepreneurial world and start-ups. We discovered that we were a start-up with an idea and that we needed investors to make that idea a commercial reality. There, we realized the difficulty of presenting and explaining a project, and we got a lot of negatives. But, in the end, we learned. | Case 7 | ||

| Facilitating factors | Financial and social support | Initially, we raised 100,000 euros through a crowd-funding system. We had 36 participating partners. We also opted for a mentorship program, which gave us visibility and more funding partners. In the next round, we raised another 250,000 euros from 40 more participating partners. | Case 1 |

| Higher and social education | I was studying architecture in Madrid, and in the summer of the second year of university, I went with a missionary to help build a school in Peru. | Case 4 | |

| Past events | At the age of 21, I suffered my first anxiety attack. I was stubborn, and, ignoring the signs, I kept on living as before. After not too many years, I was back in hospital, this time in panic. That made me rethink my life decisions. | Case 6 | |

| Professional experience | Before, I had worked 10 years in an international NPO. I was passionate about that job. | Case 8 | |

| As a computer engineer, I devoted my efforts to designing robots for artificial vision. Not only did I bring technical knowledge but also the project management skills I acquired in my role as chief engineer at a multinational company. | Case 7 | ||

| Unintended consequences | Unintended consequences | By accident, I got involved in science dissemination activities at the National Centre for Oncological Research (CNIO in Spanish). Once in the job, we realized that these activities fell a bit short, so we developed many more as there was a lot of unmet demand in unexpected segments of the public. | Case 2 |

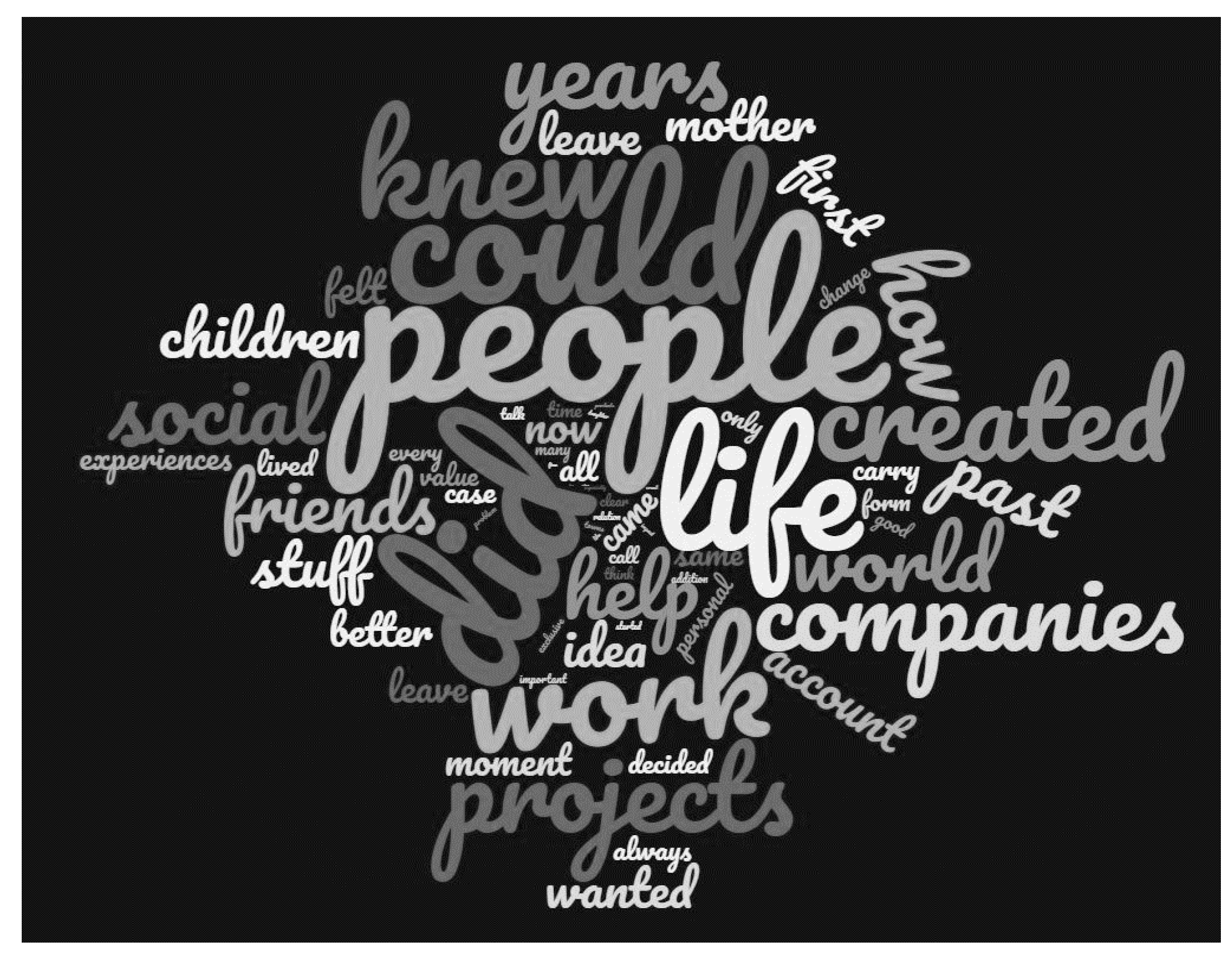

| Word | Count 1 | % | % Cum. | Word | Count | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | people | 158 | 1.56 | better | 34 | 0.34 | |

| 2 | did | 136 | 1.35 | felt | 34 | 0.34 | |

| 3 | could | 96 | 0.96 | leave | 33 | 0.33 | |

| 4 | life | 90 | 0.89 | moment | 33 | 0.33 | |

| 5 | work | 82 | 0.81 | came | 32 | 0.32 | |

| 6 | knew | 65 | 0.65 | experiences | 31 | 0.31 | |

| 7 | created | 63 | 0.63 | same | 31 | 0.31 | |

| 8 | projects | 58 | 0.58 | all | 31 | 0.31 | |

| 9 | companies | 57 | 0.57 | case | 30 | 0.30 | |

| 10 | years | 56 | 0.56 | 8.56 | carry | 30 | 0.30 |

| 11 | how | 55 | 0.55 | decided | 29 | 0.29 | |

| 12 | social | 53 | 0.53 | always | 29 | 0.29 | |

| 13 | help | 49 | 0.49 | value | 29 | 0.29 | |

| 14 | world | 49 | 0.49 | lived | 29 | 0.29 | |

| 15 | friends | 45 | 0.45 | 11.07 | every | 28 | 0.28 |

| 16 | past | 44 | 0.44 | form | 28 | 0.28 | |

| 17 | stuff | 41 | 0.41 | personal | 28 | 0.28 | |

| 18 | children | 41 | 0.41 | only | 28 | 0.28 | |

| 19 | first | 38 | 0.38 | change | 27 | 0.27 | |

| 20 | account | 38 | 0.38 | good | 26 | 0.26 | |

| 21 | idea | 38 | 0.38 | call | 26 | 0.26 | |

| 22 | now | 37 | 0.37 | time | 26 | 0.26 | |

| 23 | mother | 37 | 0.37 | many | 25 | 0.25 | |

| 24 | leave | 37 | 0.37 | clear | 24 | 0.24 | |

| 25 | wanted | 37 | 0.37 | 14.95 | talk | 24 | 0.24 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alvarez de Mon, I.; Merladet, J.; Núñez-Canal, M. Social Entrepreneurs as Role Models for Innovative Professional Career Developments. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313044

Alvarez de Mon I, Merladet J, Núñez-Canal M. Social Entrepreneurs as Role Models for Innovative Professional Career Developments. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313044

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlvarez de Mon, Ignacio, Jorge Merladet, and Margarita Núñez-Canal. 2021. "Social Entrepreneurs as Role Models for Innovative Professional Career Developments" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313044

APA StyleAlvarez de Mon, I., Merladet, J., & Núñez-Canal, M. (2021). Social Entrepreneurs as Role Models for Innovative Professional Career Developments. Sustainability, 13(23), 13044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313044