The Role of Housing in Facilitating Middle-Class Family Practices in China: A Case Study of Tianjin

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Housing Resources and Mismatched Housing Needs

2.1. The Rise of Inequality Driven by Housing

2.2. The Mismatch between Housing Need and Supply

3. The Role of Housing in Later Life and Middle-Class Family

3.1. Implications of Housing Location for Later Life

3.2. The Role of Housing in Maintaining Middle-Class Advantage

4. Site Selection

5. Recruiting Participants

6. Methods

7. Findings

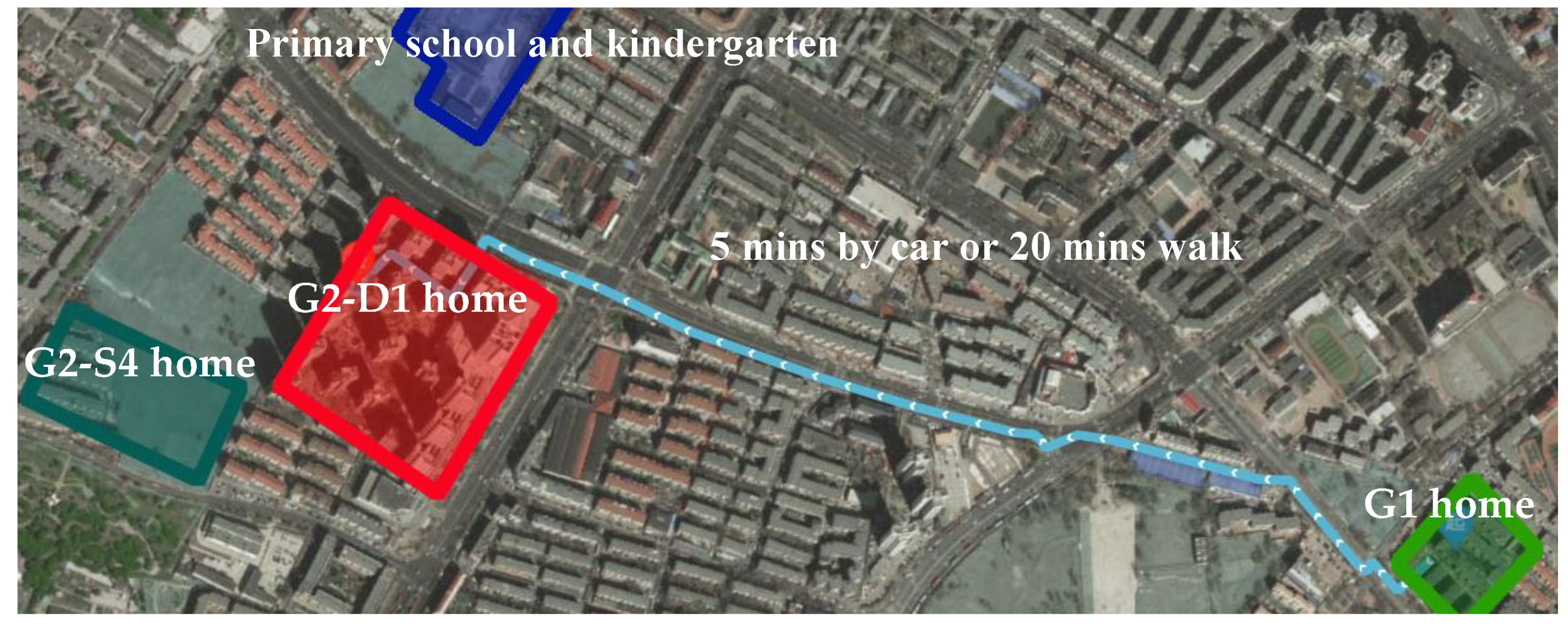

I used to live at the city’s south end, close to my workplace. Then, in 2000, I purchased a new apartment where the top schools are concentrated because I was more concerned with my son’s (G3) education at that time. I could not stop worrying about my parents’ (G1) health until I was close to retirement age, so I decided to buy another flat since it is handy for me to visit my parents. I also hope that my parents will come to live with me(G2-D2, 60 years old, in the Li family).

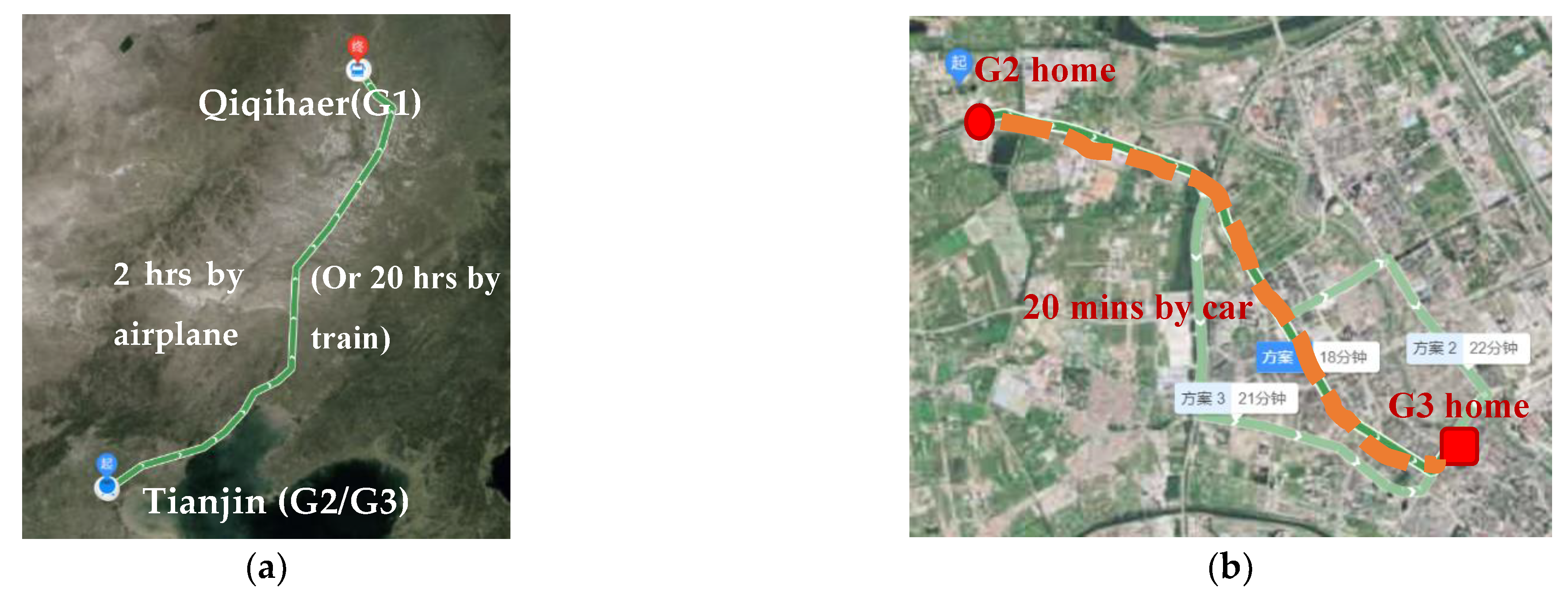

Although we moved from the big home to this 70 m2 apartment, life is so simple. Since the year our daughter-in-law was pregnant, we often travelled between Tianjin and Qingdao. After retirement, we felt the big home was not only unnecessary and also tricky to manage. Now we are delighted to live in this lovely apartment, and the space is enough for our everyday life.(G2 couple, Mr G2-68 and Mrs 67, in the Fu family).

I was used to living in my own home. It was good to live with my oldest daughter (G2-D1) because she has good hands for taking care of me, I know, but I prefer that she comes and visits me in my home. It is different … they (G2, G3) are so busy … they (G2) have to help [G3] to decorate the apartment, I can do nothing to help …(Mrs G1, 86-year-old, in the Zhao family).

My mother never looks after my son at all! My father wants to help me, but he is careless. I could not depend on them, so I quit my job and focused on taking care of him by myself. I do regret now that I asked my parents to live with me.(G3-wife in the Kong family).

My parents-in-law live with us to help to look after my son. With their help, I can focus on my work and have a competitive salary better than my husband’s. I think they are satisfied living with us because they sleep in the best room in my home [she and her husband bought this flat], and my husband, my son and I sleep in the small bedroom, but I always appreciate their support and will repay this in their later life.

8. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bostrom, M.A. Missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustinability: Introductory article in the special issue. Sustainability 2012, 8, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Dijst, M.; Geertman, S.; Cui, C. Social sustinability in an Ageing Chinese Society: Towards an Integrative Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations. World Population Ageing 2019; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/ (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Chen, L.; Han, W.-J. Shanghai: Front-runner of community-based eldercare in China. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2016, 28, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Walker, A. The need for community care among older people in China. Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 1312–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Ye, M. The development of community eldercare in Shanghai. In Community Eldercare Ecology in China; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2020; Chapter 3; pp. 55–83. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-15-4960-1_3 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Fu, Y.Y.; Chui, E.W.T. Determinants of patterns of need for home and community-based care services among community-dwelling older people in urban China: The role of living arrangement and filial piety. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 39, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, D.T.; Kirby, J.B. The relationship between living arrangement and preventive care use among community-dwelling elderly persons. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Chen, C.Y. Living arrangement preferences of elderly people in Taiwan as affected by family resources and social participation. J. Fam. Hist. 2012, 37, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izuhara, M. (Ed.) Ageing and Intergenerational Relations: Family Reciprocity from a Global Perspective; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2010; pp. 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, W.A.; Huang, Y.; Yi, D. Can millennials access homeownership in urban China? J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yi, D.; Clark, W.A.V. A homeownership paradox: Why do Chinese homeowners rent the housing they live in? Hous. Stud. 2020, 36, 1318–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; He, S.; Gan, L. Introduction to SI: Homeownership and housing divide in China. Cities 2021, 108, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council. A notification from the state council on further deepening the reform of urban housing system and accelerating housing construction No.23. In Guowuyuan Guanyu Jingyibu Shenhua Chengzhen Zhufang Zhidu Gaige Jiakuai Zhufang Jianshe De Tongzhi; State Council: Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Murie, A. The Right to Buy? Selling off Public and Social Housing; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2016; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Clapham, D.; Hegedüs, J.; Kintrea, K.; Kay, H.; Tosics, I. (Eds.) Housing Privatization in Eastern Europe; Greenwood Publishing Group: London, UK, 1996; pp. 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Bian, Y.; Zhang, W. Housing ownership and housing wealth: New evidence in transitional China. Hous. Stud. 2019, 34, 448–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z. The winners in China’s urban housing reform. Hous. Stud. 2010, 25, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ge, J. Dual institutional structure and housing inequality in transitional urban China. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2014, 37, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yi, D.; Clark, W.A.V. Multiple home ownership in Chinese cities: An institutional and cultural perspective. Cities 2020, 97, 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotta, D. Real Estate in China—Statistics and Facts; Statista Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hearne, R. A Home or a Wealth Generator? Inequality, Financialization and the Irish Housing Crisis; MURAL: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/12052/1/RH_Home%20or.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Pawson, H.; Martin, C. Rental property investment in disadvantaged areas: The means and motivations of Western Sydney’s new landlords. Hous. Stud. 2021, 36, 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doling, J.; Ronald, R. Home ownership and asset-based welfare. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2010, 25, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ronald, R.; Lennartz, C. Housing careers, intergenerational support and family relations. In Housing Careers, Intergenerational Support and Family Relations; Lennartz, C., Ronald, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; Chapter 1; pp. 1–14. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/25114 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Forrest, R. The ongoing financialization of home ownership–new times, new contexts. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2015, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, R. Generation rent and intergenerational relations in the era of housing financialization. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2018, 5, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, W.A.V.; Yi, D.; Zhang, X. Do house prices affect fertility behaviour in China? An empirical examination. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2020, 43, 423–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, R. Planning for an Ageing Society; Lund Humphries: London, UK, 2021; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A.; James, A. Housing, Residential Mobility and Ageing. In Geographies of Ageing: Social Processes and the Spatial Unevenness of Population Ageing, 1st ed.; Davies, A., James, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; Chapter 8; pp. 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, G. Bourdieu, rational action and the time–space strategy of gentrification. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2001, 26, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Edensor, T.; Cheng, J. Beyond space: Spatial (Re) production and middle-class remaking driven by Jiaoyufication in Nanjing City, China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Waley, P. Jiaoyufication: When gentrification goes to school in the Chinese inner city. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 3510–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, W.; Zhou, Z. Tianjin Ranked No.3 Accounting from the Latest Statistical Data on the Ageing Population, Sohu News. 2016. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/71260579_259491 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Duan, W.; Xu, L. Tianjinshi Minzhengju Juzhang Wu Songlin: Tianjin Yijinru Shendu Laolinghua Shehui (Wu Songlin, Director of Tianjin Civil Affairs Bureau: Tianjin Has Entered a Deeply Ageing Society), Enorth News. 2018. Available online: https://news.enorth.com.cn/system/2018/12/12/036514024.shtml (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Hurun Report. China New Middle-Class Report 2018. Available online: https://www.hurun.net/CN/Article/Details?num=F5738E8F8C63 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2014; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. Available online: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR13-4/baxter.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P.L.A. Changing perception of the rights and responsibilities in family care for older people in urban China. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2019, 31, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Xu, G.; He, L.; Zhang, M.; Lin, D. What determines the preference for future living arrangements of middle-aged and older people in urban China? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhuoga, C.; Deng, Z. Adaptations to the one-child policy: Chinese young adults’ attitudes toward elder care and living arrangement after marriage. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Requirements |

|---|---|

| Annual income | Minimum CNY 100 K per year (about GBP 11,401). |

| Occupation | Specialist or skilled job, or work at a managerial, or comparable, level, either in the state or private sectors. |

| Education | Above bachelor’s degree or college degree. |

| Hukou | Urban household registration |

| House/car | Own a house and/or car, either with a mortgage or outright ownership. Lives in a gated community. |

| Self-identity | Seeks a lifestyle rather than a living and interested in self-exploration and self-actualisation. |

| Family | Generations and Ages | Incomes of Households (Per Year) and Property Ownership |

|---|---|---|

| Li | Mr. G1—86, Mrs. G1—85. | G1 around CNY 100 K (about GBP 11 K). G1 own one apartment for their occupation. |

| Mr. G2—61, Mrs. G2 (D1)—62. | G2 around CNY 250 K (about GBP 27 K). G2 own two apartments, one for their occupation and one for their daughter (G3-D). | |

| G3-wife (34, daughter), husband (35). G4—two girls. | G3: CNY 300 K (about GBP 33 K) | |

| Hao | Mr. G1—82. | G1 around CNY 80 K (about GBP 8 K). G1 owns one apartment for occupation. |

| Mr. G2—62, Mrs. G2 (D1)—60. | G2 around CNY 400 K (about GBP 43 K). G2 own three apartments, one for living, one for a holiday home, and one in a good school district for their granddaughter’s, G4′s, education. | |

| G3-wife (34, daughter), husband (34). G4—one girl was of primary-school age. | G3: CNY 650 K (about GBP 71 K) and own one apartment for G3/G4′s occupation. | |

| Mrs. G1—83. | G1 around CNY 60 K (about GBP 6 K). G1 owns two apartments; one for Mrs. G1′s occupation, and another for G2-S1′s occupation. | |

| Mr. G2(S1)—62, Mrs. G2—60. | G2 around CNY 80 K (about GBP 8 K). G2 live in one of G1′s apartment. | |

| G3-wife (34, daughter), husband (36). | G3: CNY 150 K (about GBP 16 K). G3 live with husband’s mother, who owns the flat. | |

| Huo | Mr. G1—79, Mrs.G1—80. | G1 around CNY 70 K (about GBP 7 K). G1 live with their second daughter (G2-D2), and the apartment was bought by their youngest son (G2-S3). |

| Mr. G2 (S1)—56, Mrs. G2—60. | G2 around CNY 220 K (about GBP 24 K). G2 own two apartments, one for living, one for their son (G3-S). | |

| G3-S (25, son). | G3: CNY 130 K (about GBP 14 K). | |

| Ye | Mr. G1—85, Mrs. G1—84. | G1 around CNY 100 K (about GBP 11 K). G1 own one apartment for living. |

| Mr. G2—60, Mrs. G2(D1)—60. | G2 around CNY 180 K (about GBP 19 K). G2 own two apartments, one for living, and one is rented to increase income. | |

| G3-wife (33), husband (33, son). | G3: USD 80 K (about GBP 61 K). G3 own a house in the US and were supported financially by G2. | |

| Zhao | Mrs.G1—86. | G1 around CNY 70 K (about GBP 7 K). G1 own one apartment for living. |

| Mr. G2—63, Mrs.G2(D1)—62. | G2 around CNY 250 K (about GBP 27 K). G2 own two apartments, one for living, and one for their daughter (G3-D) and her husband. | |

| G3-wife (daughter), husband. | G3: CNY 250 K (about GBP 27 K). | |

| Wang | Mr. G1—87, Mrs. G1—87. | G1 around CNY 80 K (about GBP 8 K). G1 own one apartment for living. |

| Mr. G2 (S1)—63, Mrs. G2—61. | G2 around CNY 250 K (about GBP 27 K). G2 own two apartments, one for living, and one is rented to earn more income. | |

| G3-wife (33, daughter). | G3: CNY 200 K (about GBP 22 K). G3 owns a flat in Beijing, which was financially underpinned by G2. | |

| Kong | Mr. G2—60, Mrs. G2—59. | G2 around CNY 80 K (about GBP 8 K). G2 sold their flat to help G3 to buy their first apartment and they now live with G3. |

| G3-wife (35, daughter), husband (41). G4—one boy, and one girl. | G3: CNY 400 K (about GBP 44 K). G3 own two apartments, one for G2/G3/G4 to live as an extended family and another for rent. | |

| Han | Mr. G2—63, Mrs. G2—62. | G2 around CNY 80 K (about GBP 8 K). G2 own a flat in their hometown. |

| G3-wife (36), husband (36, son). G4—one boy | G3: CNY 700 K (about GBP 77 K). G3 own a flat and they were planning to buy a school-district apartment. | |

| Fu | Mr. G2—68, Mrs. G2—67. | G2 around CNY 220 K (about GBP 24 K). G2 own two apartments, one in Tianjin and one in Qingdao. |

| G3-wife (40), husband (41, son). G4—one girl (12). | G3: CNY 800 K (about GBP 88 K). G3 own one apartment. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Gilroy, R. The Role of Housing in Facilitating Middle-Class Family Practices in China: A Case Study of Tianjin. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313031

Wang L, Gilroy R. The Role of Housing in Facilitating Middle-Class Family Practices in China: A Case Study of Tianjin. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313031

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lu, and Rose Gilroy. 2021. "The Role of Housing in Facilitating Middle-Class Family Practices in China: A Case Study of Tianjin" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313031

APA StyleWang, L., & Gilroy, R. (2021). The Role of Housing in Facilitating Middle-Class Family Practices in China: A Case Study of Tianjin. Sustainability, 13(23), 13031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313031