Evolution of Sustainable Tourism Concepts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

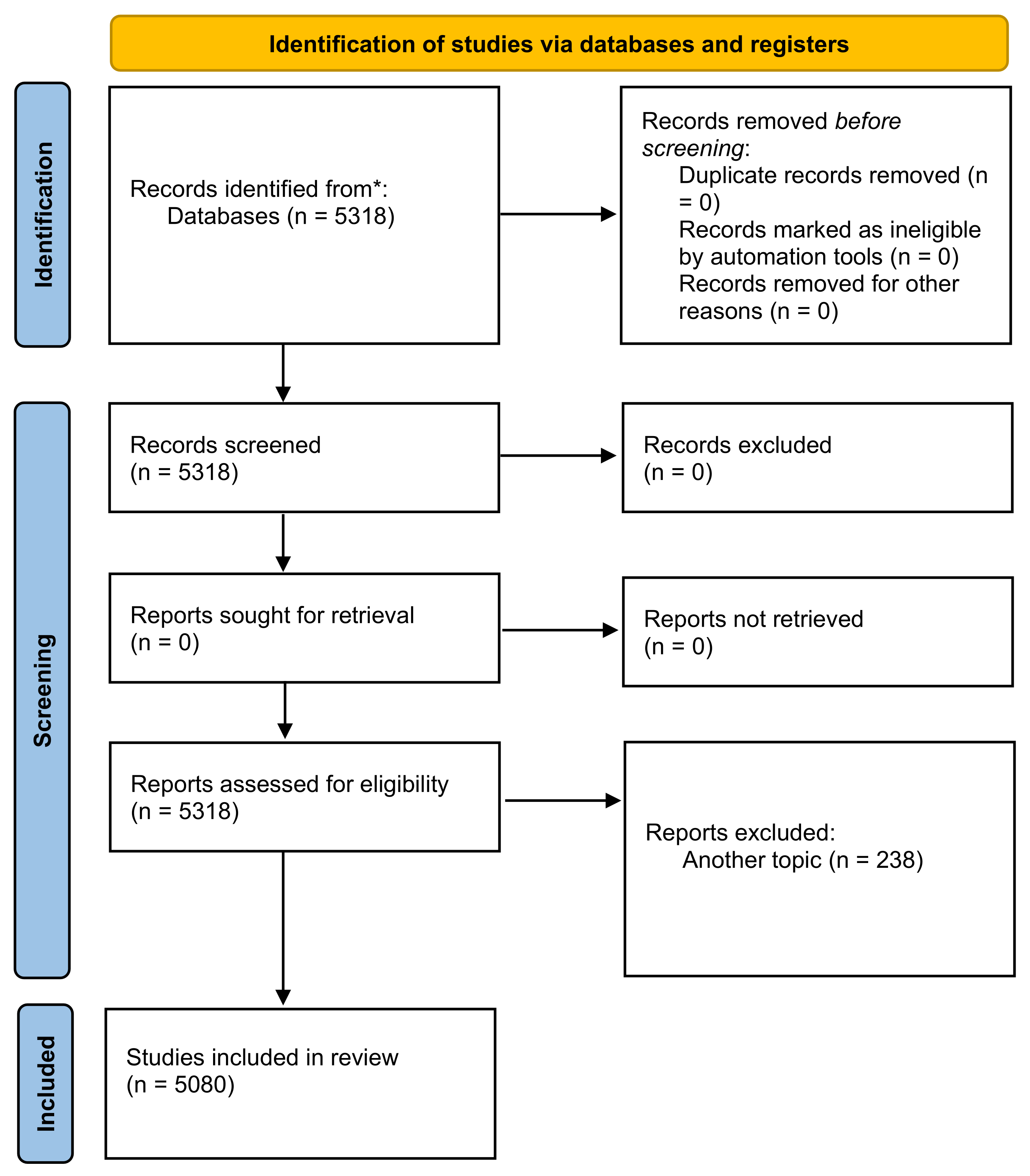

2. Research Design

2.1. Data Selection

2.2. Automated Content Analysis

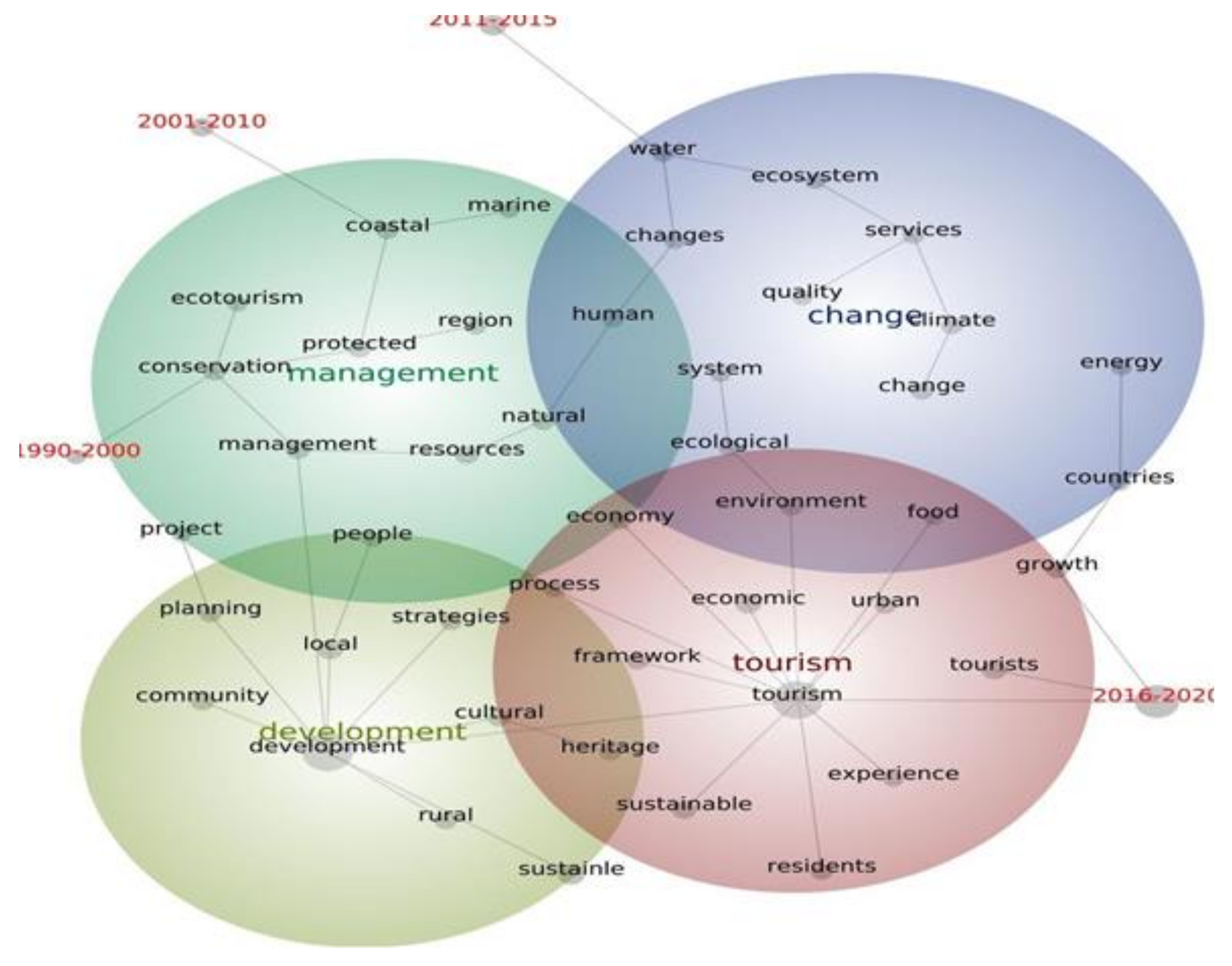

2.3. Results and Thematic Concerns in Scientific Journal Articles

3. Discussion

3.1. Evolution of Sustainable Tourism Development between 1990–2000

3.1.1. Action Management for Eco and Green Tourism

3.1.2. The Role of Supply and Value Chains of Tourism Enterprises

3.2. Evolution of Sustainable Tourism Development between 2001–2010

3.2.1. Sustainable Tourism Development Policies and Their Impact on the Rural Environment

3.2.2. Environmental Protection

3.2.3. Problematics of Mass Tourism

3.3. Evolution of Sustainable Tourism Development between 2011–2015

3.3.1. Sustainable Tourism Practices for the Protection of the Natural Environment

3.3.2. Management of Protected Areas

3.3.3. Maritime and Coastal Cultural Landscape

3.3.4. Rural Tourism Development

3.3.5. Climate Change and Coastal Development

3.3.6. Social Impacts Management for Tourism Organizations

3.3.7. Emergence of a New Form of Sustainable Tourism

3.4. Evolution of Sustainable Tourism Development between 2016–2020

3.4.1. Cultural Heritage Tourism

3.4.2. Disruptive Innovations in the Tourism Industry

3.4.3. The Role of Social Innovations and Digitalization in Tourism Industry Transformation

4. Conclusions

4.1. Research Summary

4.2. Theoretical Implications

4.3. Managerial Implications

4.4. Knowledge Gaps and Research Opportunities

4.5. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Rio+20. Report on the UN Conference on Sustainable Development. Available online: http://www.uncsd2012.org/content/documents/814UNCSD%20REPORT%20final%20revs.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Robertson, V.J. UNESCO Statement for the World Summit on Ecotourism. Available online: http://www.unep.fr/shared/publications/cdrom/WEBx0139xPA/statmnts/pdfs/rouneef (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- UNWTO—United Nations World Tourism Organisation. The Guidebook “Sustainable Tourism for Development” Brussels. Available online: http://icr.unwto.org/content/guidebook-sustainable-tourism-development (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Nathaniel, S.P.; Adedoyin, F.F. Tourism development, natural resource abundance, and environmental sustainability: Another look at the ten most visited destinations. J. Public Aff. 2020, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrandi, R.; Rinaldi, S. A Theoretical Approach to Tourism Sustainability. Conserv. Ecol. 2002, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. Ecotourism Behavior of Nature-Based Tourists: An Integrative Framework. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 792–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. Is eco-tourism sustainable? Environ. Manag. 1997, 21, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L.; Miao, L. Image matters: Incentivising green tourism behavior. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrai, E.; Buda, D.-M.; Stanford, D. Rethinking the ideology of responsible tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 992–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Pourhashemi, S.O.; Nilashi, M.; Abdullah, R.; Samad, S.; Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Aljojo, N.; Razali, N.S. Investigating influence of green innovation on sustainability performance: A case on Malaysian hotel industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Edwards, D. A comparative automated content analysis approach on the review of the sharing economy discourse in tourism and hospitality. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Gómez, A.; Ruiz-Palomo, D.; Fernández-Gámez, M.A.; García-Revilla, M.R. Sustainable tourism development and economic growth: Bibliometric review and analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Nash, N.; Whitmarsh, L. Big data or small data? A methodological review of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, P.; Santoro, L.; Thomas, A.A. Systematic literature review from 2000–2016. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blei, D.M. Probabilistic topic models. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Usai, A.; Pironti, M.; Mital, M.; Mejri, C.A. Knowledge discovery out of text data: A systematic review via text mining. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1471–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunez-Mir, G.C.; Iannone, B.V., III; Pijanowski, B.C.; Kong, N.; Fei, S. Automated content analysis: Addressing the big literature challenge in ecology and evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leximancer. Leximancer User Guide. 2020. Available online: https://info.leximancer.com/ (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/outcomedocuments/agenda21 (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Maikhuri, R.K.; Rana, U.; Rao, K.S.; Nautiyal, S.; Saxena, K.G. Promoting ecotourism in the buffer zone areas of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve: An option to resolve people—Policy conflict. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 7, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.W.; Hendrickson, T.; Castillo, A. Ecotourism and conservation in Amazonian Perú: Short-term and long-term challenges. Environ. Conserv. 1997, 24, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpole, M.J.; Goodwin, H.J. Local economic impacts of dragon tourism in Indonesia. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.E. Development of a model system for touristic hunting revenue collection and allocation. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearing, S.; Wearing, M. Decommodifying Ecotourism: Rethinking global-local interactions with host Communities. Soc. Leis. 1999, 22, 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Interpretation and sustainable tourism: Functions, examples and principles. J. Tour. Stud. 1998, 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jurowski, C.; Olsen, M.D. Scanning the environment of tourism attractions: A content analysis approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1995, 4, 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, F.; Roberts, L. Help or Hindrance? Sustainable Approaches to Tourism Consultancy in Central and Eastern Europe. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthman, J. Representing Crisis: The Theory of Himalayan Environmental Degradation and the Project of Development in Post-Rana Nepal. Dev. Chang. 1997, 28, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A. Tourism development and natural capital. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welford, R.; Ytterhus, B. Conditions for the transformation of eco-tourism into sustainable tourism. Eur. Environ. 1998, 8, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Wall, G. Ecotourism: Towards congruence between theory and practice. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juda, L. Considerations in Developing a Functional Approach to the Governance of Large Marine Ecosystems. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 1999, 30, 89–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wescott, G. The development and initial implementation of Australia’s ‘integrated and comprehensive’ Oceans Policy. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2000, 43, 853–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.R. Coastal zone management for the new century. Ocean Coast. Manag. 1997, 37, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenchington, R.; Crawford, D. On the meaning of integration in coastal zone management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 1993, 21, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Tourism, Environment, and Sustainable Development. Environ. Conserv. 1991, 18, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, M.T. Tourism and economic development: A survey. J. Dev. Stud. 1998, 34, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M. Consumerism and Sustainable Tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2000, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenosky, D.B. Nature-based tourists’ use of interpretive services: A means-end investigation. J. Tour. Stud. 1998, 9, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Von Frantzius, I. World Summit on Sustainable Development Johannesburg 2002: A Critical Analysis and Assessment of the Outcomes. Environ. Polit. 2004, 13, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Sustainable performance index for tourism policy development. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Framke, W. The Destination as a Concept: A Discussion of the Business-related Perspective versus the Socio-cultural Approach in Tourism Theory. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2002, 2, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, M.; Dubini, P. Integrating heritage management and tourism at Italian cultural destinations. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2010, 12, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S. Sustainable Tourism Development in Developing Countries: Some Aspects of Energy Use. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawley, M.; Gillmor, D.A. Integrated rural tourism: Concepts and Practice. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Wornell, R.; Youell, R. Re-conceptualising rural resources as countryside capital: The case of rural tourism. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellecco, I.; Mancino, A. Sustainability and tourism development in three Italian destinations: Stakeholders’ opinions and behaviours. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 2201–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Momsen, J.H. Tourism and Poverty Reduction: Issues for Small Island States. Tour. Geogr. 2008, 10, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitto, J.I. International Cooperation for Sustainable Coastal and Marine Management in East Asia. Geogr. Rev. Jpn. 2003, 76, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.T.; Courtney, C.A.; Salamanca, A. Experience with Marine Protected Area Planning and Management in the Philippines. Coast. Manag. 2002, 30, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavovic, B.C.; Boonzaier, S. Confronting coastal poverty: Building sustainable coastal livelihoods in South Africa. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2007, 50, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S.K.; Chipeniuk, R. Mountain tourism: Toward a conceptual framework. Tour. Geogr. 2005, 7, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.; Queiroz, C.; Pereira, H.; Vicente, L. Ecosystem Services and Human Well-Being: A Participatory Study in a Mountain Community in Portugal. Ecol. Soc. 2005, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieger, T.; Wittmer, A. Air transport and tourism—Perspectives and challenges for destinations, airlines and governments. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2006, 12, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadaroo, J.; Seetanah, B. Transport infrastructure and tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, D.; Craig, D. The third way and the third world: Poverty reduction and social inclusion in the rise of ‘inclusive’ liberalism. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2004, 11, 387–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascante, D.M. Beyond Growth: Reaching tourism-led development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 1141–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaiwa, J.E. The Socio-cultural Impacts of Tourism Development in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2005, 2, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, M.B.; Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Bouris, A.; Reyes, A.M. HIV/AIDS and Tourism in the Caribbean: An Ecological Systems Perspective. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, A.L. Economies of Desire: Sex and Tourism in Cuba and the Dominican Republic; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, S.; Kunc, M.; Jones, E.; Tiffin, S. Supporting innovation for tourism development through multi-stakeholder approaches: Experiences from Africa. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minciu, R.; Pădurean, M.; Popescu, D.; Hornoiu, R. Demand for Vacations/Travel in Protected Areas–Dimension of Tourists’ Ecological Behavior. Amfit. Econ. J. 2012, 14, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, A.M.; Prideaux, B. Indigenous ecotourism in the Mayan rainforest of Palenque: Empowerment issues in sustainable development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J.; Neuts, B.; Nijkamp, P.; Shikida, A. Determinants of trip choice, satisfaction and loyalty in an eco-tourism destination: A modelling study on the Shiretoko Peninsula, Japan. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 107, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.-P.; Dubois, G. Consumer behaviour and demand response of tourists to climate change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-J.; Liaw, S.-C. What is the Value of Eco-Tourism? An Evaluation of Forested Trails for Community Residents and Visitors. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 871–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakzad, S.; Pieters, M.; Van Balen, K. Coastal cultural heritage: A resource to be included in integrated coastal zone management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 118, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.J.; Lima, J.; Silva, A.L. Landscape and the rural tourism experience: Identifying key elements, addressing potential, and implications for the future. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1217–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnet, I.C.; Konold, W. New approaches to support implementation of nature conservation, landscape management and cultural landscape development: Experiences from Germany’s southwest. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAreavey, R.; McDonagh, J. Sustainable Rural Tourism: Lessons for Rural Development. Sociol. Rural. 2011, 51, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGehee, N.G.; Knollenberg, W.; Komorowski, A. The central role of leadership in rural tourism development: A theoretical framework and case studies. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1277–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komppula, R. The role of individual entrepreneurs in the development of competitiveness for a rural tourism destination—A case study. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazcarro, I.; Hoekstra, A.; Chóliz, J.S. The water footprint of tourism in Spain. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.; Gomes, C.; Guerreiro, S.; O’Riordan, T. Are we all on the same boat? The challenge of adaptation facing Portuguese coastal communities: Risk perception, trust-building and genuine participation. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeoshenkova, V.; Newton, A. Overview of erosion and beach quality issues in three Southern European countries: Portugal, Spain and Italy. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 118, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucrezi, S.; Saayman, M.; Van der Merwe, P. Managing beaches and beachgoers: Lessons from and for the Blue Flag award. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCombes, L.; Vanclay, F.; Evers, Y. Putting social impact assessment to the test as a method for implementing responsible tourism practice. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 55, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razumova, M.; Ibáñez, J.L.; Palmer, J.R.-M. Drivers of environmental innovation in Majorcan hotels. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1529–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugores, M.; García, D. The Impact of Innovation on Firms’ Performance: An Analysis of the Hotel Sector in Majorca. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timms, B.F.; Conway, D. Slow Tourism at the Caribbean’s Geographical Margins. Tour. Geogr. 2012, 14, 396–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Özdemir, G.; Yilmaz, M.; Yalçin, M.; Alvarez, M.D. Stakeholders’ Perception of Istanbul’s Historical Peninsula as a Sustainable Destination. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2015, 12, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Swain, R.B.; Yang-Wallentin, F. Achieving sustainable development goals: Predicaments and strategies. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galli, A.; Đurović, G.; Hanscom, L.; Knežević, J. Think globally, act locally: Implementing the sustainable development goals in Montenegro. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caust, J.; Vecco, M. Is UNESCO World Heritage recognition a blessing or burden? Evidence from developing Asian countries. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Gheitasi, M.; Timothy, D.J. Urban regeneration through heritage tourism: Cultural policies and strategic management. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 18, 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Fagnoni, E. Managing World Heritage Site stakeholders: A grounded theory paradigm model approach. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; Sakellarios, N.; Pritchard, M. The theory of planned behaviour in the context of cultural heritage tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2015, 10, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomi, A.; Tussyadiah, I.; Ling, E.C.; Miller, G.; Lee, G. x = (tourism_work) y = (sdg8) while y = true: automate(x). Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movono, A.; Hughes, E. Tourism partnerships: Localizing the SDG agenda in Fiji. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Mills, J.; Guidi, G.; Rodríguez-Gonzálvez, P.; Barsanti, S.G.; González-Aguilera, D. Geoinformatics for the conservation and promotion of cultural heritage in support of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 142, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, R.S.; Lück, M.; Schänzel, H.A. A conceptual framework of tourism social entrepreneurship for sustainable community development. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, N.; Roblek, V.; Papachashvili, N. Decision support based on data mining for post COVID-19 tourism industry. In Proceedings of the XV International SAUM Conference, Niš, Serbia, 9–10 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peterlin, J.; Meško, M.; Dimovski, V.; Roblek, V. Automated content analysis: The review of the big data systemic discourse in tourism and hospitality. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 38, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.; Rainoldi, M.; Egger, R. Virtual reality in tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 586–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranmer, E.E.; Dieck, M.C.T.; Fountoulaki, P. Exploring the value of augmented reality for tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Kumar, N.; Chen, J.; Gong, Z.; Kong, X.; Wei, W.; Gao, H. Realizing the Potential of Internet of Things for Smart Tourism with 5G and AI. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, V.; Karam, E. New-age technologies-driven social innovation: What, how, where, and why? Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, D.A.L.; Morita, M.M.; Bilmes, G.M. Virtual museums. Captured reality and 3D modeling. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 45, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The “war over tourism”: Challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagosa, F. The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Entrepreneurs in rural tourism: Do lifestyle motivations contribute to management practices that enhance sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, F.M.Y.; Rivera, J.P.R.; Gutierrez, E.L.M. Mapping stakeholders’ roles in governing sustainable tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. International Tourism Receipts Worldwide from 2006 to 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/273123/total-international-tourism-receipts/ (accessed on 19 September 2021).

- Kaushal, V.; Srivastava, S. Hospitality and tourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on challenges and learnings from India. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, P.L. Tourists’ perception of time: Directions for design. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sethia, N.K.; Srinivas, S. Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, U.; Filimonau, V.; Vujičić, M.D. A mindful shift: An opportunity for mindfulness-driven tourism in a post-pandemic world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, C.; Huang, Q.; Morrison, A.M. Smart tourism destination experiences: The mediating impact of arousal levels. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.R.; Park, S. Mindfulness training for tourism and hospitality frontline employees. Ind. Commer. Train. 2020, 52, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.; Hassan, A.; Ekis, E. Augmented reality for relaunching tourism post-COVID-19: Socially distant, virtually connected. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020, 12, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, N.; Tošić, M.; Nejković, V. AR-enabled mobile apps for robot coordination. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference with International Participation Knowledge Management and Informatics, Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia, 2–4 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, N.; Roblek, V.; Khokhobaia, M.; Gagnidze, I. AR-enabled mobile apps to support post COVID-19 tourism. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Advanced Technologies, Systems and Services in Telecommunications (TELSIKS), Niš, Serbia, 20–22 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Theme | Hits | Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Development | 14,100 | development, tourism, sustainable, local, economic, community, social, environment, rural, cultural, heritage, residents, framework, strategies, process, economy, experience |

| Management | 7257 | management, resources, protected, natural, region, conservation, planning, coastal, eco-tourism, people, marine, project |

| Change | 4763 | change, climate, services, ecological, system, ecosystem, human, changes, water, quality |

| Tourists | 4606 | tourists, growth, urban, countries, energy, food |

| (a) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept | Rel. Freq. (%) | Strength (%) | Prominence |

| coastal | 18 | 9 | 4 |

| conservation | 16 | 7 | 3.7 |

| protected | 16 | 6 | 3 |

| management | 20 | 5 | 2.8 |

| planning | 11 | 5 | 2.7 |

| resources | 15 | 5 | 2.6 |

| local | 20 | 4 | 2.5 |

| community | 16 | 4 | 2.4 |

| tourism | 72 | 3 | 1.7 |

| economic | 13 | 3 | 1.5 |

| (b) | |||

| Concept | Rel. Freq. (%) | Strength (%) | Prominence |

| conservation | 6 | 23 | 1.3 |

| protected | 6 | 20 | 1.1 |

| resources | 7 | 20 | 1.1 |

| region | 6 | 20 | 1.1 |

| management | 7 | 17 | 1 |

| local | 8 | 16 | 0.9 |

| economic | 7 | 16 | 0.9 |

| community | 6 | 15 | 0.9 |

| tourism | 33 | 14 | 0.8 |

| sustainable | 6 | 10 | 0.6 |

| (c) | |||

| Concept | Rel. Freq. (%) | Strength (%) | Prominence |

| conservation | 4 | 29 | 1 |

| change | 4 | 25 | 0.9 |

| community | 5 | 22 | 0.8 |

| management | 6 | 22 | 0.8 |

| local | 6 | 21 | 0.8 |

| social | 5 | 21 | 0.8 |

| tourism | 31 | 21 | 0.7 |

| economic | 6 | 20 | 0.7 |

| resources | 4 | 20 | 0.7 |

| sustainable | 7 | 20 | 0.7 |

| (d) | |||

| Concept | Rel. Freq. (%) | Strength (%) | Prominence |

| growth | 6 | 68 | 1.3 |

| sustainable | 13 | 67 | 1.3 |

| social | 8 | 63 | 1.2 |

| rural | 6 | 61 | 1.2 |

| tourism | 49 | 61 | 1.2 |

| economic | 9 | 59 | 1.2 |

| community | 7 | 57 | 1.1 |

| local | 9 | 56 | 1.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roblek, V.; Drpić, D.; Meško, M.; Milojica, V. Evolution of Sustainable Tourism Concepts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12829. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212829

Roblek V, Drpić D, Meško M, Milojica V. Evolution of Sustainable Tourism Concepts. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12829. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212829

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoblek, Vasja, Danijel Drpić, Maja Meško, and Vedran Milojica. 2021. "Evolution of Sustainable Tourism Concepts" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12829. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212829

APA StyleRoblek, V., Drpić, D., Meško, M., & Milojica, V. (2021). Evolution of Sustainable Tourism Concepts. Sustainability, 13(22), 12829. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212829