A Bibliometric Overview of Tourism Family Business

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Tourism Family Business Conceptualization

2.1. Family Business Objectives and Characteristic Behaviors of Family Owners and Management

2.2. Family Business Assets, Ownership, and Governance Structure

2.3. External Effects: Geographical Location, Natural Environment, and Tourist Destination

2.4. Tourist Perspective and Behavior

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

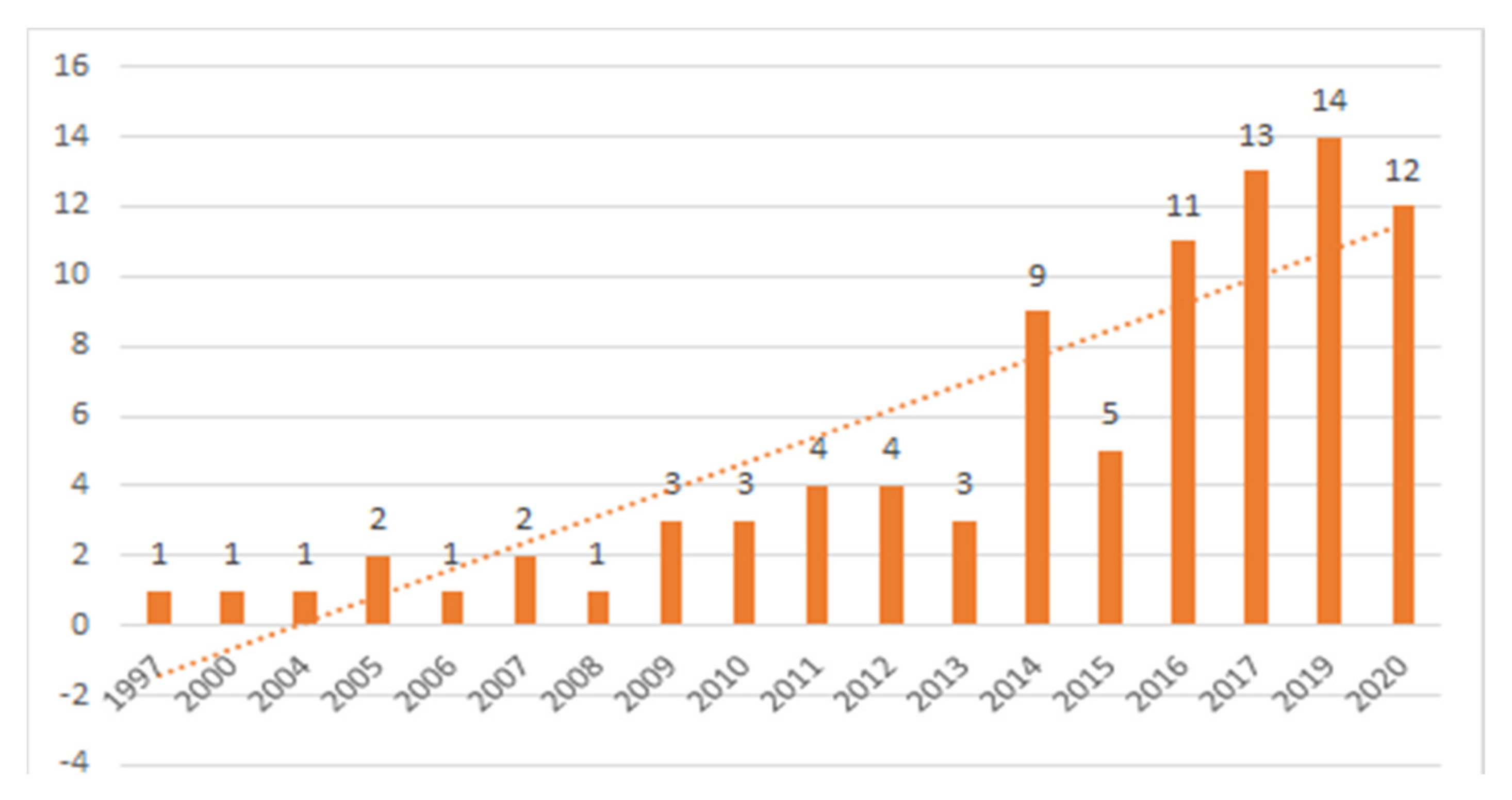

4.1. Evolution of Published Papers and Main TFB Research Streams

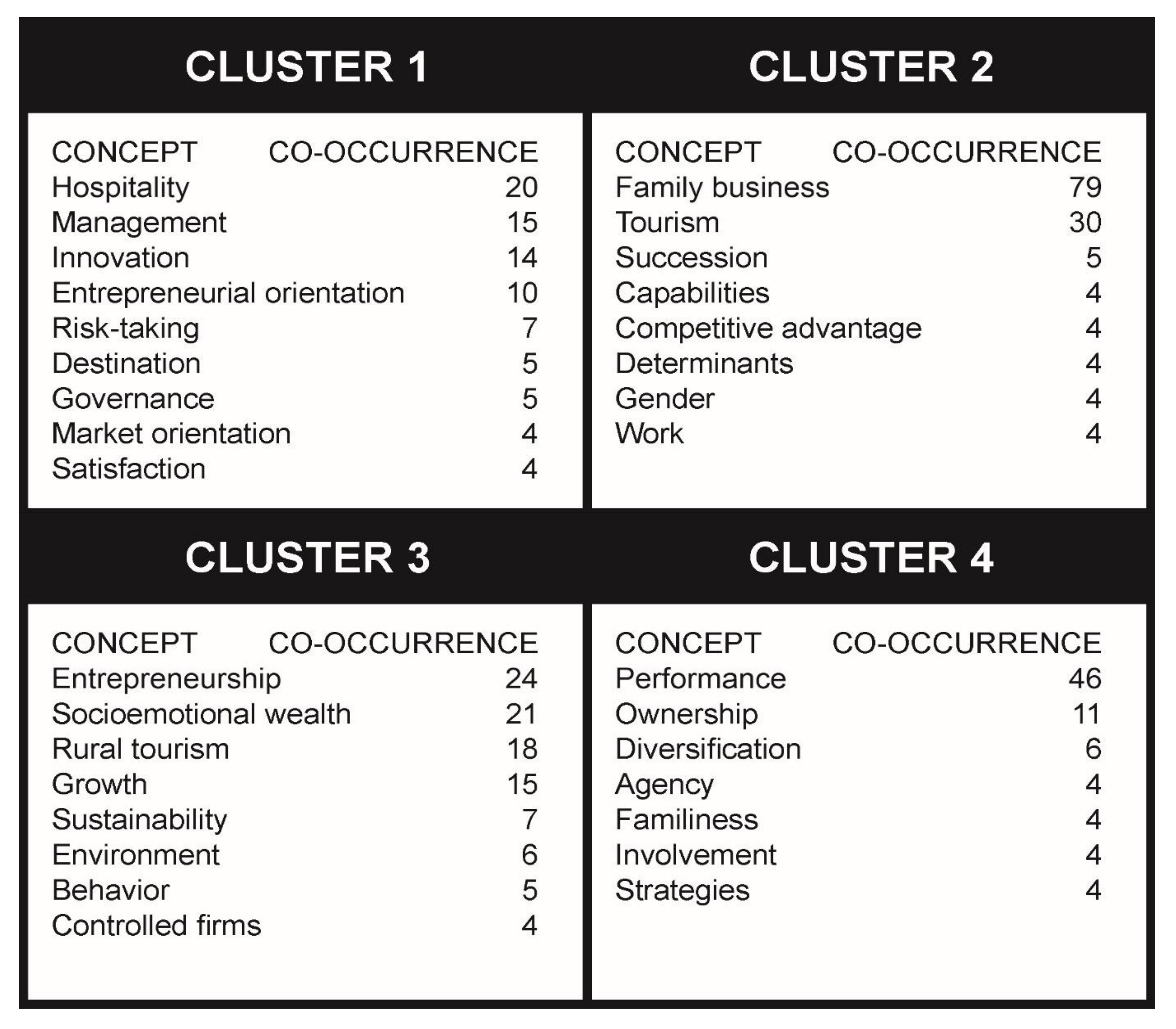

4.2. Cluster 1: Entrepreneurship, Marketing Orientation, and Innovation Performance

4.3. Cluster 2: Capabilities and Competitiveness

4.4. Cluster 3: Sustainability

4.5. Cluster 4: Strategy and Economic Performance

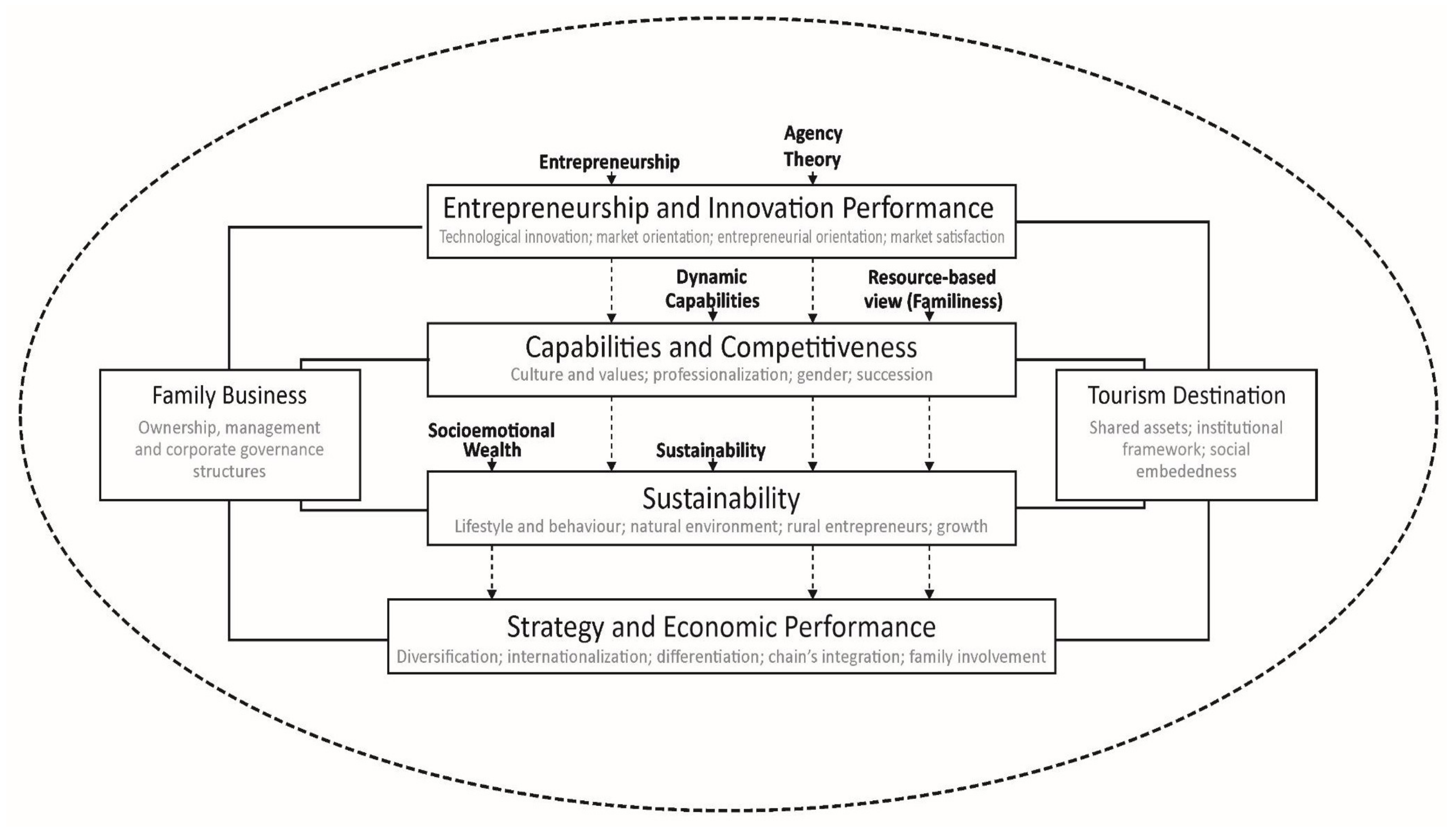

4.6. An Integrative Framework for Studying Tourist Family Businesses

- RQ1: What insights about TFB founders’ decision-making processes can be gained through different theoretical lenses, such as SEW and/or stewardship theory?

- RQ2: How does the legacy and culture of the family affect the objectives, asset investment, and innovation performance of TFB?

- RQ3: What impact do environmental competitive forces at the national, regional, industry, and tourist destination level have on TFB orientation, resources, and capabilities, and how do they affect innovation performance?

- RQ4: How is the embeddedness of TFB in a tourist destination translated into more innovation capabilities and innovation performance? Specifically, which TFB characteristics allow them to absorb and integrate external shared knowledge competences with the firm’s internal ones to boost innovation performance?

- RQ5: What are the moderating effects of defining TFB elements—ownership, management, and governance—on the relationship between dynamic capabilities and innovation performance?

- RQ6: What ownership and control structures, related to family involvement, are the most suitable for promoting dynamic capabilities and innovation performance in TFB?

- RQ7: How does the professionalization of the manager and the development of adequate corporate governance mechanisms impact the development of dynamic capabilities in TFB?

- RQ8: What effect does family involvement have on the learning mechanisms underlying dynamic capabilities, considering intangible assets such as the family’s values and culture?

- RQ9: How can innovation or dynamic capabilities be used to involve young heirs in TFB?

- RQ10: Which strategies, structures, and practices can TFB use to reduce potential conflicts in a succession process, and extract the benefits of knowledge diversity for dynamic capabilities development?

- RQ11: What are the main characteristics, behaviors, and assets of women’s managerial capabilities in TFB?

- RQ12: Can gender-diverse management teams provide more dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage for TFB?

- RQ13: Which specific strategies, capabilities, and governance mechanisms influence sustainability performance (economic, social, and environmental) in TFB?

- RQ14: How do environmental and social performance objectives interact with innovation strategies?

- RQ15: What role do dynamic capabilities play in the sustainability performance of TFB?

- RQ16: Which sections of the tourism chain are most in need of assistance to execute strategies aimed at improving sustainability performance in TFB?

- RQ17: How is sustainability performance approached in the different subsectors of the family H&T industry?

- RQ18: Which contingent factors help strengthen family managerial involvement and positively affect its economic performance?

- RQ19: How do the different roles played by different family members and their life aspirations impact TFB performance?

- RQ20: As viewed through the SEW theoretical lens, what are the TFB characteristics that have the greatest impact on the achievement of a balanced economic, social, and environmental performance?

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Research Avenues

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Della Corte, V.; Del Gaudio, G.; Sepe, F.; Sciarelli, F. Sustainable Tourism in the Open Innovation Realm: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguilera, N.P.; Anzardo, L.E.P.; Sosa, P.B.; Campdesuñer, R.P. Bibliometric Analysis of Scientific Production on Tourism and Tourism Product. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Estevão, C.; Costa, C.; Fernandes, C. Competitiveness in the Tourism Sector: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2019, 7, 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Memili, E.; Patel, P.C.; Koç, B.; Yazıcıoğlu, İ. The Interplay between Socioemotional Wealth and Family Firm Psychological Capital in Influencing Firm Performance in Hospitality and Tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V.; Fakhar Manesh, M.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Dabic, M. The Journal of Family Business Management: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2020, 11, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Hayton, J.C.; Salvato, C. Entrepreneurship in Family vs. Non–Family Firms: A Resource–Based Analysis of the Effect of Organizational Culture. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2004, 28, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J. Family Business in Tourism: State of the Art. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, R.; Claver-Cortés, E.; Quer, D.; Rienda, L. Family ownership and Spanish hotel chains: An analysis of their expansion through internationalization. Universia Bus. Rev. 2018, 59, 1698–5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A. A Contextualisation of Entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2006, 12, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Shaw, G.; Page, S.J. Understanding Small Firms in Tourism: A Perspective on Research Trends and Challenges. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, J.; Prügl, R. Innovation Activities during Intra-Family Leadership Succession in Family Firms: An Empirical Study from a Socioemotional Wealth Perspective. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2015, 6, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Nikolakis, W.; Peters, M.; Zanon, J. Trade-Offs between Dimensions of Sustainability: Exploratory Evidence from Family Firms in Rural Tourism Regions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1204–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Kallmuenzer, A. Entrepreneurial Orientation in Family Firms: The Case of the Hospitality Industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga, B.; Amit, R.; Trujillo, M.-A.; Guzmán, A. Governance of Family Firms. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2015, 7, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cabrera-Suárez, M.K.; García-Almeida, D.J.; De Saá-Pérez, P. A Dynamic Network Model of the Successor’s Knowledge Construction From the Resource- and Knowledge-Based View of the Family Firm. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2018, 31, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casprini, E.; Dabic, M.; Kotlar, J.; Pucci, T. A Bibliometric Analysis of Family Firm Internationalization Research: Current Themes, Theoretical Roots, and Ways Forward. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Haynes, K.T.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.L.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional Wealth and Business Risks in Family-Controlled Firms: Evidence from Spanish Olive Oil Mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koseoglu, M.A.; Rahimi, R.; Okumus, F.; Liu, J. Bibliometric Studies in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Okumus, F.; Wu, K.; Köseoglu, M.A. The Entrepreneurship Research in Hospitality and Tourism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, R.; Güttel, W.H. The Dynamic Capability View in Strategic Management: A Bibliometric Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigos-Simon, F.J.; Narangajavana-Kaosiri, Y.; Narangajavana, Y. Quality in Tourism Literature: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benckendorff, P.; Zehrer, A. A Network Analysis of Tourism Research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguí-Amortegui, L.; Clemente-Almendros, J.A.; Medina, R.; Grueso Gala, M. Sustainability and Competitiveness in the Tourism Industry and Tourist Destinations: A Bibliometric Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aparicio, G.; Iturralde, T.; Sanchez-Famoso, V. Innovation in Family Firms: A Holistic Bibliometric Overview of the Research Field. Eur. J. Fam. Bus. 2019, 9, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmo, G.C.; Arcese, G.; Valeri, M.; Poponi, S.; Pacchera, F. Sustainability in Tourism as an Innovation Driver: An Analysis of Family Business Reality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbershon, T.G.; Williams, M.; MacMillan, I.C. A Unified Systems Perspective of Family Firm Performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbershon, T.G.; Williams, M.L. A Resource-Based Framework for Assessing the Strategic Advantages of Family Firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1999, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H.; De Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Wright, M. The Ability and Willingness Paradox in Family Firm Innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D.; Donaldson, L. Toward a Stewardship Theory of Management. AMR 1997, 22, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms: Theoretical Dimensions, Assessment Approaches, and Agenda for Future Research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Hayton, J.C.; Neubaum, D.O.; Dibrell, C.; Craig, J. Culture of Family Commitment and Strategic Flexibility: The Moderating Effect of Stewardship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, J.H.; Jaskiewicz, P. Emotional Returns and Emotional Costs in Privately Held Family Businesses: Advancing Traditional Business Valuation. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 21, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, W. Socio-Emotional Wealth and Family: Revisiting the Connection. Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2016, 14, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barros, I.; Hernangómez, J.; Martin-Cruz, N. A Theoretical Model of Strategic Management of Family Firms. A Dynamic Capabilities Approach. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2016, 7, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, A.; Vecchiarini, M.; Gast, J.; Campopiano, G.; De Massis, A.; Kraus, S. Innovation in Family Firms: A Systematic Literature Review and Guidance for Future Research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 317–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón-Zornosa, C.; Forés, B.; Puig-Denia, A.; Camisón-Haba, S. Effects of Ownership Structure and Corporate and Family Governance on Dynamic Capabilities in Family Firms. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1393–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, R.W.; Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-471-01557-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ollenburg, C.; Buckley, R. Stated Economic and Social Motivations of Farm Tourism Operators. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Schuckert, M. Tourism Entrepreneurs’ Perception of Quality of Life: An Explorative Study. Tour. Anal. 2014, 19, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.; Carlsen, J.; Getz, D. Family Business Goals in the Tourism and Hospitality Sector: Case Studies and Cross-Case Analysis from Australia, Canada, and Sweden. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 15, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Petersen, T. Identifying Industry-Specific Barriers to Inheritance in Small Family Businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 17, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Peters, M. Innovativeness and Control Mechanisms in Tourism and Hospitality Family Firms: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 70, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacosa, E.; Ferraris, A.; Monge, F. How to Strengthen the Business Model of an Italian Family Food Business. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2309–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowka, G.; Kallmünzer, A.; Zehrer, A. Enterprise Risk Management in Small and Medium Family Enterprises: The Role of Family Involvement and CEO Tenure. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 1213–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C.; Forés, B.; Puig-Denia, A. Return on Capital in Spanish Tourism Businesses: A Comparative Analysis of Family vs Non-Family Businesses. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bensemann, J.; Hall, C.M. Copreneurship in Rural Tourism: Exploring Women’s Experiences. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2010, 2, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Peters, M.; Buhalis, D. The Role of Family Firm Image Perception in Host-Guest Value Co-Creation of Hospitality Firms. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2410–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J.; Getz, D.; Ali-Knight, J. The Environmental Attitudes and Practices of Family Businesses in the Rural Tourism and Hospitality Sectors. J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memili, E.; Fang, H. “Chevy”; Koç, B.; Yildirim-Öktem, Ö.; Sonmez, S. Sustainability Practices of Family Firms: The Interplay between Family Ownership and Long-Term Orientation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J. Characteristics and Goals of Family and Owner-Operated Businesses in the Rural Tourism and Hospitality Sectors. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Nilsson, P.A. Responses of Family Businesses to Extreme Seasonality in Demand: The Case of Bornholm, Denmark. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J. Whitbread: Routines and Resource Building on the Path from Brewer to Retailer. Manag. Organ. Hist. 2018, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A. Exploring Drivers of Innovation in Hospitality Family Firms. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1978–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Costanzo, L.A.; Karatas-Özkan, M. Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Sustainable Entrepreneurship within the Context of a Developing Economy. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Shin, W. Marketing Tradition-Bound Products through Storytelling: A Case Study of a Japanese Sake Brewery. Serv. Bus. 2015, 2, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vrontis, D.; Culasso, F.; Giacosa, E.; Stupino, M. Entrepreneurial Exploration and Exploitation Processes of Family Businesses in the Food Sector. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2759–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R.; Assaker, G.; O’Connor, P. Are Family and Nonfamily Tourism Businesses Different? An Examination of the Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy–Entrepreneurial Performance Relationship. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 388–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banki, M.B.; Ismail, H.N. Understanding the Characteristics of Family Owned Tourism Micro Businesses in Mountain Destinations in Developing Countries: Evidence from Nigeria. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 13, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Getz, D.; Petersen, T. Growth and Profit-Oriented Entrepreneurship among Family Business Owners in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujan, I. Family Business in Tourism Characteristics—The Owner’s Perspective. Ekon. Pregl. 2020, 71, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A. Revising the “Five-Fold Framework” in Human Resource Management Practices: Insights from a Small-Scale Travel Agent. Tour. Anal. 2014, 19, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, A. Performance Measurement and Management in Small Companies of the Service Sector; Evidence from a Sample of Italian Hotels. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2019, 24, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-B.; Doh, K.-R.; Kim, K.-H. Successful Managerial Behaviour for Farm-Based Tourism: A Functional Approach. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcese, G.; Valeri, M.; Poponi, S.; Elmo, G.C. Innovative Drivers for Family Business Models in Tourism. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2020, 11, 402–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, D.; Chaudhry, S.; Crick, J.M. Risks/Rewards and an Evolving Business Model: A Case Study of a Small Lifestyle Business in the UK Tourism Sector. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2018, 21, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. Succession in Tourism Familiy Business: The Motivation of Succeeding Family Members. Tour. Rev. 2005, 60, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masset, P.; Uzelac, I.; Weisskopf, J.-P. Family Ownership, Asset Levels, and Firm Performance in Western European Hospitality Companies. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 867–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baggio, R.; Valeri, M. Network Science and Sustainable Performance of Family Businesses in Tourism. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Madanoglu, M.; Daniele, R.; Lashley, C. The Influence of Family Tradition and Psychological Traits on Entrepreneurial Intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, K.; Park, S.; Kim, D.-Y. Antecedents and Consequences of Managerial Behavior in Agritourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Kraus, S.; Peters, M.; Steiner, J.; Cheng, C.-F. Entrepreneurship in Tourism Firms: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Performance Driver Configurations. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F.; Kallmuenzer, A.; Peters, M. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in Hospitality: The Relevance of Entrepreneurs’ Quality of Life. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F.; Kallmuenzer, A.; Peters, M.; Petry, T.; Clauss, T. Regional Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: How Family Firm Embeddedness Triggers Ecosystem Development. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C.; Forés, B. Is Tourism Firm Competitiveness Driven by Different Internal or External Specific Factors?: New Empirical Evidence from Spain. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; Bressan, A. Innovation in the Context of Small Family Businesses Involved in a ‘Niche’ Market. Int. J. Bus. Environ. 2014, 6, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Z. Entrepreneurship in the Small and Medium-Sized Hotel Sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 328–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapalska, A.M.; Brozik, D. Managing Family Businesses in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry: The Transitional Economy of Poland. Proc. Rij. Fac. Econ. J. Econ. Bus. 2007, 25, 141–165. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, M.; Schmitz, B.; Spencer, T. Networks, Clusters and Innovation in Tourism: A UK Experience. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimerl, P.; Peters, M. Shaping the Future of Alpine Tourism Destinations’ next Generation: An Action Research Approach. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2019, 67, 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Vrontis, D.; Bresciani, S.; Giacosa, E. Tradition and Innovation in Italian Wine Family Businesses. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 1883–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betton, M.E.; Branston, J.R.; Tomlinson, P.R. Owner–Manager Perceptions of Regulation and Micro-Firm Performance: An Exploratory View. Compet. Chang. 2021, 25, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte Alonso, A. Socioeconomic Development in an Ultra-Peripheral European Region: The Role of a Food Regulatory Council as a Social Anchor. Community Dev. 2014, 45, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeset, A.B. “For Better or for Worse”—The Role of Family Ownership in the Resilience of Rural Hospitality Firms. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 20, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasella, B.; Ali, A. The Importance of Personal Values and Hospitableness in Small Foodservice Businesses’ Social Responsibility. Hosp. Soc. 2019, 9, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presas, P.; Guia, J.; Muñoz, D. Customer’s Perception of Familiness in Travel Experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presas, P.; Muñoz, D.; Guia, J. Branding Familiness in Tourism Family Firms. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 18, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Frehse, J. Small and Family Businesses as Service Brands: An Empirical Analysis in the Hotel Industry. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2011, 12, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, S.; Köseoglu, M.A.; Okumus, F. Identification of Growth Factors for Small Firms: Evidence from Hotel Companies on an Island. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2016, 29, 994–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, W.; Qiu, J. Semantic Information Retrieval Research Based on Co-Occurrence Analysis. Online Inf. Rev. 2014, 38, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainaghi, R.; Köseoglu, M.A.; d’Angella, F.; Lawerh Tetteh, I. Foundations of Hospitality Performance Measurement Research: A Co-Citation Approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lai, N.; Zuo, J.; Chen, G.; Du, H. Characteristics and Trends of Research on Waste-to-Energy Incineration: A Bibliometric Analysis, 1999–2015. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier-Fuentes, H.; Hormiga, E.; Miravitlles, P.; Blanco-Mesa, F. International Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review of the Research Field. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2019, 13, 381–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. Paradoxes of Tourism in Goa. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundin, E.; Wigren-Kristoferson, C. Where the Two Logics of Institutional Theory and Entrepreneurship Merge: Are Family Businesses Caught in the Past or Stuck in the Future? S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2013, 16, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hallak, R.; Assaker, G. Family vs. Non-Family Business Owners’ Commitment to Their Town: A Multigroup Invariance Analysis. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 618–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Peters, M. Entrepreneurial Behaviour, Firm Size and Financial Performance: The Case of Rural Tourism Family Firms. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters, M.; Bichler, B.F. Innovation Research in Tourism: Research Streams and Actions for the Future. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 41, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, A.; Mensah, H.K.; Ayuuni, A.M. The Moderating Role of Social Network on the Relationship between Innovative Capability and Performance in the Hotel Industry. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2018, 13, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbin Praničević, D.; Mandić, A. ICTs in the Hospitality Industry: An Importance-Performance Analysis among Small Family-Owned Hotels. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2020, 68, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Zhan, Z.; Fong, P.S.W.; Liang, T.; Ma, Z. Planned Behaviour of Tourism Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions in China. Appl. Econ. 2016, 48, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, R.S.; Jensen, T.C. Honoring the Kun Lun Way: Cross-Cultural Organization Development Consulting to a Hospitality Company in Datong, China. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2009, 45, 305–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Raich, M.; Märk, S.; Pichler, S. The Role of Commitment in the Succession of Hospitality Businesses. Tour. Rev. 2012, 67, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-M. (Mindy); Tseng, C.-Y.; Chen, L.-C. Choosing between Exiting or Innovative Solutions for Bed and Breakfasts. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiçek, D.; Zencir, E.; Kozak, N. Women in Turkish Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmawati, E.; Suliyanto; Suroso, A. Direct and Indirect Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Family Involvement and Gender on Family Business Performance. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Kallmuenzer, A.; Buhalis, D. Hospitality Entrepreneurs Managing Quality of Life and Business Growth. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2014–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanrıvermis, H.; Sanlı, H. A Research on the Impacts of Tourism on Rural Household Income and Farm Enterprises: The Case of the Nevsehir Province of Turkey. J. Agric. Rural. Dev. Trop. Subtrop. (JARTS) 2007, 108, 169–189. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, S.; Yagi, H.; Kiminami, A.; Garrod, G. Farm Diversification and Sustainability of Multifunctional Peri-Urban Agriculture: Entrepreneurial Attributes of Advanced Diversification in Japan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ertuna, B.; Karatas-Ozkan, M.; Yamak, S. Diffusion of Sustainability and CSR Discourse in Hospitality Industry: Dynamics of Local Context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2564–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Getz, D. Characteristics and Goals of Rural Family Business Owners in Tourism and Hospitality: A Developing Country Perspective. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2008, 33, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.N.; Mohd Puzi, M.A.; Banki, M.B.; Yusoff, N. Inherent Factors of Family Business and Transgenerational Influencing Tourism Business in Malaysian Islands. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2019, 17, 624–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsos, G.A.; Carter, S.; Ljunggren, E. Kinship and Business: How Entrepreneurial Households Facilitate Business Growth. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2014, 26, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Álvaro, J.-J.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Sáez-Martínez, F.-J. Rural Tourism: Development, Management and Sustainability in Rural Establishments. Sustainability 2017, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crawford, A.; Naar, J. Exit Planning of Lifestyle and Profit-Oriented Entrepreneurs in Bed and Breakfasts. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2016, 17, 260–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognazzo, A.; Neubaum, D.O. Family Business Leaders’ Metaphors and Firm Performance: Exploring the “Roots” and “Shoots” of Symbolic Meanings. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2020, 33, 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banki, M.B.; Ismail, H.N.; Muhammad, I.B. Coping with Seasonality: A Case Study of Family Owned Micro Tourism Businesses in Obudu Mountain Resort in Nigeria. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, M. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry: Do Family Control and Financial Condition Matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, H.; Memili, E.; Steeger, J. Expert Insights on the Determinants of Cooperation in Family Firms in Tourism and Hospitality Sector. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2015, 3, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza Aguilar, J.L. Corporate Social Responsibility Practices Developed by Mexican Family and Non-Family Businesses. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2018, 9, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diéguez-Soto, J.; Fernández-Gámez, M.A.; Sánchez-Marín, G. Family Involvement and Hotel Online Reputation. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2017, 20, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, R.; Quer, D.; Rienda, L. The Influence of Family Character on the Choice of Foreign Market Entry Mode: An Analysis of Spanish Hotel Chains. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2020, 26, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienda, L.; Claver, E.; Andreu, R. Family Involvement, Internationalisation and Performance: An Empirical Study of the Spanish Hotel Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. The Effects of Involvement and Social Support on Frontline Employee Outcomes: Evidence from the Albanian Hotel Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2009, 10, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza-Aguilar, J.L.; García-Pérez-de-Lema, D.; Duréndez, A. The Effect of Accounting Information Systems on the Performance of Mexican Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Family Firms: An Exploratory Study for the Hospitality Sector. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 1104–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-S.; Chiang, C.-F.; Huangthanapan, K.; Downing, S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: The Case Study of Family-Owned Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 48, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Zehrer, A. Innovation and Service Experiences in Small Tourism Family Firms. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism, Competitiveness, and Societal Prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowka, G.; Zehrer, A. Tourism Family-Business Owners’ Risk Perception: Its Impact on Destination Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, A.; Melin, L.; Nordqvist, M. Entrepreneurship as Radical Change in the Family Business: Exploring the Role of Cultural Patterns. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2001, 14, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton-Miller, I.L.; Miller, D. Family Firms and Practices of Sustainability: A Contingency View. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2016, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiczy, N.D.; Hack, A.; Kellermanns, F.W. What Makes a Family Firm Innovative? CEO Risk-Taking Propensity and the Organizational Context of Family Firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Organizational Forms and Investment Decisions. J. Financ. Econ. 1985, 14, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, A.; Torchia, M.; Jimenez, D.G.; Kraus, S. The Role of Human Capital on Family Firm Innovativeness: The Strategic Leadership Role of Family Board Members. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 261–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arteaga, R.; Menéndez-Requejo, S. Family Constitution and Business Performance: Moderating Factors. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2017, 30, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujan, I. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Socioemotional Dimensions in Small Family Hotels: Do They Impact Business Performance? Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2020, 33, 1925–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cruz, T.; Clemente-Almendros, J.A.; Puig-Denia, A. Family Governance Systems: The Complementary Role of Constitutions and Councils. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F. Knowledge Accumulation in Family Firms: Evidence from Four Case Studies. Int. Small Bus. J. 2008, 26, 433–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sciascia, S.; Mazzola, P.; Kellermanns, F.W. Family Management and Profitability in Private Family-Owned Firms: Introducing Generational Stage and the Socioemotional Wealth Perspective. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Kotlar, J.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Wright, M. Innovation Through Tradition: Lessons from Innovative Family Businesses and Directions for Future Research. AMP 2016, 30, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, D.; Xu, X.; Mehrotra, V. When Is Human Capital a Valuable Resource? The Performance Effects of Ivy League Selection among Celebrated CEOs. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 930–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.A.; Celdrán-Bernabeu, M.A.; Mazón, J.-N.; Perles-Ivars, Á.F. Smart Destinations and the Evolution of ICTs: A New Scenario for Destination Management? Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1581–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Journal | NC | Authors | Year | Theoretical Lens(es) | Sample | Main Variables | Main Results | Family Business Concept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOURISM MANAGEMENT | 210 | Thomas, R; Shaw, G; Page, SJ | 2011 | SMEs | Inter-, multi- and disciplinary studies that contribute to current understanding of small firms in tourism | Small tourism firms, future research agenda | Three areas for future research: i) development (application of theories of business growth or the development of explanations for structural changes within the sector); ii) emerging areas (informal economy, local economic development and policy formation for the sector); iii) established areas topics where research on certain aspects lags behind (such as small firms and sustainability) or because there has been a sustained effort which has borne fruit but requires development, notably theoretically (such as lifestyle businesses) | Firms that may be owned and managed by a family (a structure) |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENTREPRENEURIAL BEHAVIOR & RESEARCH | 98 | Morrison, A | 2006 | Entrepreneurship | Application of a systematic framework | Entrepreneurial process, industry setting, organisational context, entrepreneurial socio-economic outcomes | Entrepreneurial process in family business depends on cultural, industry and organizational context | Within the context of entrepreneurship, family businesses may be established for social and economic purposes, and mesh domestic and business dimensions towards the attainment of lifestyle goals |

| BRITISH FOOD JOURNAL | 94 | Vrontis, D; Bresciani, S; Giacosa, E | 2016 | Innovation strategy | Three semi-structured interviews with the CEO; direct observations in wine shops and restaurants; documentation from websites, interviews in magazines and websites with other family members | Consumer perception, cultural identity, tradition, product innovation, process innvation, territory | Innovation and tradition are not opposites; on the contrary, a blend of the two has been crucial in achieving and maintaining a sustainable competitive advantage | Family businesses has specific mechanisms and dynamics (Chrisman et al., 2012). In its innovation, the company is strictly connected to the “familiness” factor (Dunn, 1995; Sirmon and Hitt, 2003) |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT | 64 | Altinay, L; Madanoglu, M; Daniele, R; Lashley, C | 2012 | Entrepreneurship | 205 British university students pursuing tourism and hospitality management degree at a major British university | Family tradition, locus of control, tolerance ambiguity, innovativeness, need for achievement, risk taking, entrepreneurial intention | Family entrepreneurial background and innovation influence the intention to start a new business; there is positive relationship between tolerance of ambiguity and risk taking propensity; and a negative relationship between locus of control and risk taking propensity. It’s important to take a more holistic approach when researching the factors that influence entrepreneurial intention | Socio-cultural factors and in particular family tradition in the same line of business is identified as an influential factor on the entrepreneurial behaviours of individuals. So, family tradition was measured, based on the question whether anybody in the family has a prior entrepreneurship experience |

| CURRENT ISSUES IN TOURISM | 27 | Peters, M; Kallmuenzer, A | 2015 | Entrepreneurship | 17 interviews with family owner-managers of hospitality family firms throughout the state of Tyrol, Austria, from different Tyrolean regions and from businesses of different sizes and age. | Performance, entrpreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial behavior | Family firms in hospitality and tourism are peculiar. Their embeddedness in the destinations and regions outlines their entrepreneurial behavior | (i) Ownership and management, (ii) majority of shares, (iii) family members in the business (Chua, Chrisman and Sharma, 1999; Litz, 1995; Miller, Le Breton-Miller and Scholnick, 2007; Westhead and Cowling, 1998) |

| BRITISH FOOD JOURNAL | 21 | Giacosa, E; Ferraris, A; Monge, F | 2017 | Innovation strategy | Two semi-structured interviews with the CEO; direct observations in shops; documentations, and past interviews in magazines and websites with other family members | Food innovation, customer perception, cultural identity, tradition, territory | The company is characterized by a strong combination of tradition and innovation, both in products and processes. Its competitiveness is the result of a balanced management of innovation, in respect of the family’s values, thanks to the active presence of two family generations. | Family businesses has specific features, mechanisms, and behavior (Chrisman et al., 2012), and a heterogeneous nature – stemming from a merging of family and business (Chua et al., 2012) |

| Journal | NC | Authors | Year | Theoretical Lens(es) | Sample | Main Variables | Main Results | Family Business Concept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANNALS OF TOURISM RESEARCH | 157 | Getz, D; Carlsen, J | 2005 | Family Business | A priori determination of keywords (owner, owner–operator, family, gender, small business, entrepreneur, business growth/failure) summarizes the literature review paper’s about family business in tourism | Family business, family dynamics, entrepreneurship, development | Four major themes identified in the literature are discussed: i) small and family business operations, ii) links to entrepreneurship, iii) roles and responsibilities of family members, iv) destination or community development | Three-dimensional developmental model of family business (Gersick, Davis, Hampton and Lansberg, 1997) |

| JOURNAL OF FAMILY BUSINESS STRATEGY | 55 | Hauck, J; Prugl, R | 2015 | SEW | 81 owner-managers of familiy firms in the Austrian tourism industry | Perceived suitability of the succession phase for innovation activities, adaptabilty, intergenerational authority, family member’s closeness to the firm, history of family bonds, investment in social ties | Family adaptability and its member’s closeness to the firm are associated with the succession phase as opportunity for innovation | Firms entirely owned (100%) and managed by the family |

| CURRENT ISSUES IN TOURISM | 26 | Ahmad, SZ | 2015 | Entrepreneurship | 115 small- and medium-sized hotels owners/managers from three cities in the United Arab Emirates | SMSHs and SMEs motivation and business challenges | Characteristics of the owners/managers of SMSHs in the UAE: male, young and middle-aged with secondary- and higher-education levels, new to the tourism industry. Motivations for the business ventures: wanting to be financially independent, become one’s own boss, involvement in family business and the opportunities of the hotel business. Key business challenges: stiff competition in the hotel industry, increased operating costs, reduced demand and lack of skilled employees. Key strategies employed to face these challenges: offering competitive pricing, improving the marketing and channels of promotion, enhancing the quality of service and providing superior customer service. | Small and medium companies |

| JOURNAL OF BRAND MANAGEMENT | 17 | Presas, P; Munoz, D; Guia, J | 2011 | Corporate branding | A tourism-based family company (Grup Mas de Torrent) based in Catalonia (Spain) | Familiness, corporate branding, sustainable development, business growth, tourism experience | Familiness support sustainable practices; being a family business is essencial for the guest | Familiness (Habbershon and Williams, 1999) |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT | 14 | Kallmuenzer, A | 2018 | Innovation | 22 hospitality family firm owner-managers in Western Austria | Drivers of innovation, competitive advantage, entrepreneurial family | Entrepreneurial family and employees are key drivers for innovation as actors internal to the firm, but also the guests and regional competitors as external drivers provide comprehensive innovation input. These innovation efforts are perceived to stimulate growth and business development | Families are owners and managers at the same time and that; a minimum of two members are active in the management (Chua et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2007; Westhead and Cowling, 1998) |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GENDER AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP | 13 | Bensemann, J; Hall, CM | 2010 | Entrepreneurship | 10 interviews with female copreneurs and 108 questionnaires from tha New Zealand owners from the farmstay or B&B sector of rural tourism businesses | Copreneurial expectations, roles and responsabilities of women’s experiences specifically | Rural tourism accommodation sector in New Zealand is characterised by lifestylers and copreneurs running their businesses as a “hobby”; non-economic and lifestyle motivations are important stimuli to business formation; a gendered ideology persists, as copreneurial couples appear to engage in running the accommodation business using traditional gender-based roles mirroring those found in the private home | Couples in business together (copreneurs) are one form of family business |

| Journal | NC | Authors | Year | Theoretical Lens(es) | Sample | Main Variables | Main Results | Family Business Concept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOURISM MANAGEMENT | 240 | Getz, D; Carlsen, J | 2000 | Managerial perception, objectives and expectations | 198 family-owned business of Western Australia | Lifestyle, family-related goals, profitabilty, succession plans | The motivations of entrepreneurs in rural tourism are predominantely lifestyle-related, and profitability driven, being the family succession not clearly defined | A business-owned business which is owner operated or one family owns controlling interests |

| ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT | 74 | Alsos, Gry Agnete; Carter, Sara; Ljunggren, Elisabet | 2014 | Entrepreneurial household strategy and Familiness | 4 case studies of rural regions of Norway and Scotland | Household strategy, family business growth and diverfication, resources and capabilities, networks, trust, behavioural control | Entrepreneurial household strategy for supporting the development of new family business growth through its management and use of business portfolios and resources, the use of family kinship relations and the mitigation of risks and uncertainty through self-imposed controls of the activities and behaviour. | A business-owned business which is owner operated or one family owns controlling interests |

| ANNALS OF TOURISM RESEARCH | 55 | Wilson, D | 1997 | Etnographic approach | Perceptions of tourists and the host community; participant information | Environmental protection, local community health | Low-budget tourism as the best option to involve small indigenuos family business in North Goa, just for the protection of environment and the local community wealth and sociocultural values, in spite of the government’s promotion of hotel development. | Small indigenous family business (analyzed them, but didn’t conceptualize FF) |

| SUSTAINABILITY | 22 | Villanueva-Alvaro, Juan-Jose; Mondejar-Jimenez, Jose; Saez-Martinez, Francisco-Jose | 2018 | Sustainability | 396 Spanish small rural tourism companies | Environmental management practices and outcomes | Identification of actors which determine the sustainability behaviour of rural establishments. The establishments of low categories with more sustainable managerment practices and outcomes | Entrepreneurs from small and medium companies (analyzed them, but didn’t conceptualize FF) |

| TOURISM MANAGEMENT | 17 | Park, Duk-Byeong; Doh, Kyung-Rok; Kim, Kyung-Hee | 2014 | Managerial behaviour | 225 Korean tourism farms | Product/service development, business planning and evaluation, promotions, human resource management, networking, cost reductions and financial performance | The results reveal that managers have primarily focused on product/service development, human resource management and cost reduction; and only product/service development and promotions have a significant impact on financial results | A business-owned business which is owner operated or one family owns controlling interests |

| JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE TOURISM | 16 | Kallmuenzer, A; Nikolakis, W; Peters, M; Zanon, J | 2017 | Socio-emotional wealth (SEW) | 152 rural family firms of Western Austria | Economic, social and environmental performance trade-offs | The results show that after satisfying financial requirements, these firms are predominantly motivated by environmental and social objectives in their decision-making, instead of obtaining greater utility from these outcomes than additional financial profits. The findings show that respondents place greater importance on environmental legal regulations, and the impact on ecosystems and jobs creation and stakeholder satisfaction. | Firms having at least two family members actively involved in managing the firm and the family owning at least 50% of the company |

| Journal | NC | Authors | Year | Theoretical Lens(es) | Sample | Main Variables | Main Results | Family Business Concept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOURISM MANAGEMENT | 84 | Getz, D; Nilsson, PA | 2004 | Seasonality of tourist demand | Survey with 84 owners of different activities related to tourism, from two municipalities on Bornholm; structured interviews with 33 owner-operators | Demand, extreme seasonality, family business, strategy | Extreme seasonality has implications for family life, business growth or viability | A business venture owned and/or operated by one person, couple or family (Barry, 1975) |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT | 31 | Singal, M | 2014 | Instrumental theory | The matching of ESG data, with Standard and Poor’s credit ratings data and stock return data, stock files results in a final panel sample of 580 firm-years related to the hospitality and tourism sector on U.S. | Family firm, corporate social responsability, financial performance, financial condition, slack resources, credit ratings | Family firms are financially stronger, but don’t invest more in CSR than nonfamily firms | Fractional ownership by founding family or descendants plus membership on the board of directors (Anderson and Reeb, 2003) |

| JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH | 23 | Hallak, R; Assaker, G; O’Connor, P | 2014 | Entrepreneurship | 298 usable responses from family-owned (158) and nonfamily-owned (143) small-and medium-sized tourism enterprise owners in regional South Australia | Entrepreneurial self-efficacy, enterprise performance | Tourism business owners’ Entrepreneur Self Efficacy (ESE) have a significant positive effect on enterprise performance, being an important predictor of business performance | “Is your business a family-owned business?” (Getz and Carlsen, 2000) |

| TOURISM MANAGEMENT | 14 | Kallmuenzer, A; Kraus, S; Peters, M; Steiner, J; Cheng, CF | 2019 | Entrepreneurship | 113 owner-managers of SMEs tourism firms from from the tourism and hospitality industry in the Austrian Chamber of Commerce’s database of owner-manager led firms; 13 face-to-face interviews with these respondents | Entrepreneurial orientation, financial resource, environmental uncertainty, performance | Six different configuritons, which can be grouped grouped into high or low environmental uncertainty settings and highlight the relevance of multidimensional Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), financial endowment, and personal and professional networks to high firm performance | Small and medium companies |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM ADMINISTRATION | 8 | Karatepe, OM | 2009 | Psychological involvement and Social support | 107 fulltime frontline employees of the 4- and 5-star hotels of Albania | Job involvement, family involvement, work social support, family social support, job satisfaction, family satisfaction, turnover intentions | Family involvement and family support increased family satisfaction, while job involvement and work support amplified job satisfaction. Work support did not significantly affect family satisfaction and family support did not demonstrate any significant relationship with job satisfaction. There are significant negative effects of both work and family support on turnover intentions. Lower job satisfaction led to higher turnover intentions. In contrast, family satisfaction was found to exacerbate employees’ turnover intentions | Ownership structure (independently/family-owned) |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY AND TOURISM ADMINISTRATION | 7 | Crawford, A; Naar, J | 2016 | Entrepreneurship and Cognitive Dissonance Theory | 120 B&B owner/operators, innkeepers, and entrepreneurs from U.S. market | Job satisfaction, work life balance, family involvement, exit planning | B&B entrepreneurs are aware of and engaged in exit planning and the majority of Bed and Breakfast entrepreneurs are lifestyle entrepreneurs | “Are you the owner/entrepreneur?” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forés, B.; Breithaupt Janssen, Z.; Takashi Kato, H. A Bibliometric Overview of Tourism Family Business. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212822

Forés B, Breithaupt Janssen Z, Takashi Kato H. A Bibliometric Overview of Tourism Family Business. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212822

Chicago/Turabian StyleForés, Beatriz, Zélia Breithaupt Janssen, and Heitor Takashi Kato. 2021. "A Bibliometric Overview of Tourism Family Business" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212822

APA StyleForés, B., Breithaupt Janssen, Z., & Takashi Kato, H. (2021). A Bibliometric Overview of Tourism Family Business. Sustainability, 13(22), 12822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212822