1. Introduction

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) is currently one of the main focus areas for policy makers worldwide.

In December 2016, the European Commission formed a high-level expert group (HLEG) to develop an overarching and detailed EU sustainable finance strategy. On 31 January 2018, the HLEG released its final report [

1]. This report presented an holistic view of European sustainable finance and established two financial system imperatives. The first is to increase finance’s commitment to long-term, inclusive development. The second goal is to improve financial stability by fostering the awareness about environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues while making investment decisions. The United Nations-backed Principles for Responsible Investment Directive 2016/234 incorporates ESG considerations into the EU legislative framework. The increased attention by policy makers toward this topic has also been followed by an improved appetite of financial investors for ESG funds. According to the ECB’s Financial Stability Review, the Asset Under Management (AUM) of these funds has increased by 170%, soaring from 500 billion USD in 2015 to more than 1.3 trillion USD in 2020 [

2].

As suggested by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Inquiry and the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), we can refer to ESG as the following: (i) Environmental (E) issues are related to the natural environment and natural systems; (ii) Social (S) issues refer to the rights of people and communities; and (iii) Governance (G) issues pertain to corporate governance of firms.

The proposal for a disclosure law, in particular, seeks to incorporate environmental, social and governance aspects into investors’ and asset managers’ decision-making processes. It also seeks to improve financial intermediaries’ disclosure obligations to end-investors in terms of sustainability risks and investment goals. In this regard, this paper aims to review the current legislative framework on ESG in Europe as related to banks.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first policy review assessment on ESG. We thus contribute to the literature on the three different factors related to ESG (environmental, social and governance factors) by providing a critical assessment of the legislative framework proposed about ESG practices in Europe, comparing and contrasting the different policies proposed in different countries all over Europe, to expose their pros and cons and inspire further best practices for both policy makers and practitioners.

This paper is presented as follows. The next section will provide an overview of the literature on the principles while

Section 3 summarises the guidelines and regulations issued in recent years with regard to these principles, with a focus on Europe.

Section 4 compares and contrasts the regulations implemented at a national level by each European country. The last section discusses and concludes by identifying room for improvement and offering suggestions to guide policy makers’ actions.

2. Literature Review

The literature related to social responsibility of private companies is extremely rich and articulated. The first studies focused on the need to integrate aspects related to social responsibility issues into strategic planning processes and management systems of companies in order to properly consider the expectations of all stakeholders. The neoclassical position, whose main advocate was Friedman, maintained that the only objective that a private company should pursue is to use resources in activities that lead to the maximization of profits abiding by the basic rules of a civil society as enshrined into the laws and ethical principles [

3]. An antithetical position as compared to the neoclassical one was expressed by Freeman that argued that a firm should consider not only the interests of its shareholders but also those of the plurality of actors involved in its activities (employees, customers, local communities, etc.) [

4]. Following this theory, some authors such as Post, Preston and Sachs argued that companies should apply the principles of social, environmental and governance responsibility regardless of the costs involved [

5]. Other authors, in particular Porter and Kramer, have argued that the primary objective of private companies should be the profits maximization while trying to follow the principles of social, environmental responsibility and corporate governance [

6].

At the beginning, the studies in the banking sector were also specifically focused on social responsibility issues. They mainly analysed the correlation between banks’ financial performance and the integration of the social responsibility principles within their management processes and systems. The results of these studies have led to divergent conclusions; Simpsons and Kohers [

7] found a strong positive correlation between the introduction of socially responsible practices and the financial performance of banks. However, the result of the work of Esteban-Sánchez et al. conducted between 2005 and 2010 on a sample of 154 banks from 22 countries that enacted social responsibility principles, showed mixed results that rejected the positive relationship between the adoption of these principles and the financial performance of banks [

8].

Some authors employ a “reputation-building” hypothesis, according to which sound environmental management can help firms improve their reputations and thus their performance (Konar and Cohen, 2001) [

9]; however, there is a dearth of unifying findings regarding the relationship between ESG and bank performance. Dell’Atti et al. (2017) [

10] discovered a positive correlation between reputation and social performance and a negative correlation between corporate governance and environmental performance. The authors assert that this unfavorable link is the result of banks’ ineffective implementation of environmental awareness practices. On the other hand, Forcadell and Aracil (2017) [

11] found that responsible banks gain from reputational benefits that are reflected in their financial success.

Fayad et al. (2017) [

12], in particular, make a strong connection between their findings and the stakeholder theory because voluntary activities to strengthen banks’ social responsibilities are taken in the interest of social, economic and environmental protection. Additionally, they conclude that a bank that operates sustainably and responsibly will earn above-average profits, which will motivate the bank’s management to invest in ESG activities aimed at resolving environmental and social problems and achieving that mission through a credible and quality management system.

Recently, the focus of research has been broadened by shifting more to environmental issues. Relevant studies include those by Jeucken [

13], Jo et al. [

14], Finger et al. [

15] and Laguir et al. [

16] that focused on creation of value by banks that carry out activities having a positive environmental impact. Hernández et al. [

17] analysed the relationship between the adoption of ESG principles (thus considering environmental as well as social responsibility issues) by banks and the impact on their financial performance. This analysis found empirical evidence of a positive correlation between the banks’ Tobin Q and the adoption of the ESG principles. At the same time, it also found a negative correlation between the adoption of these principles and the creation of shareholders’ value. Brogi and Lagasio [

18] focused on the impact of the implementation of ESG practices on the financial performance of a sample of US banks compared to a sample of industrial firms. This study found empirical evidence of a high positive correlation between ESG policies and banks’ financial performance; the study also found that this correlation is even more pronounced in banks than in industrial firms.

There are few contributions in the literature related to the role of ESG practices in bank regulation. Kern and Fischer [

19] focused on initiatives that regulation and prudential supervision should undertake to encourage banks to foster the development of business practices that have a positive environmental sustainability impact.

3. Current European Regulatory Framework for Banking Institutions with Reference to the ESG Principles

Specific disclosure requirements have been introduced in the current European regulatory framework for industrial companies and for banks alike in order to support the implementation of the so-called European Green Deal [

20].

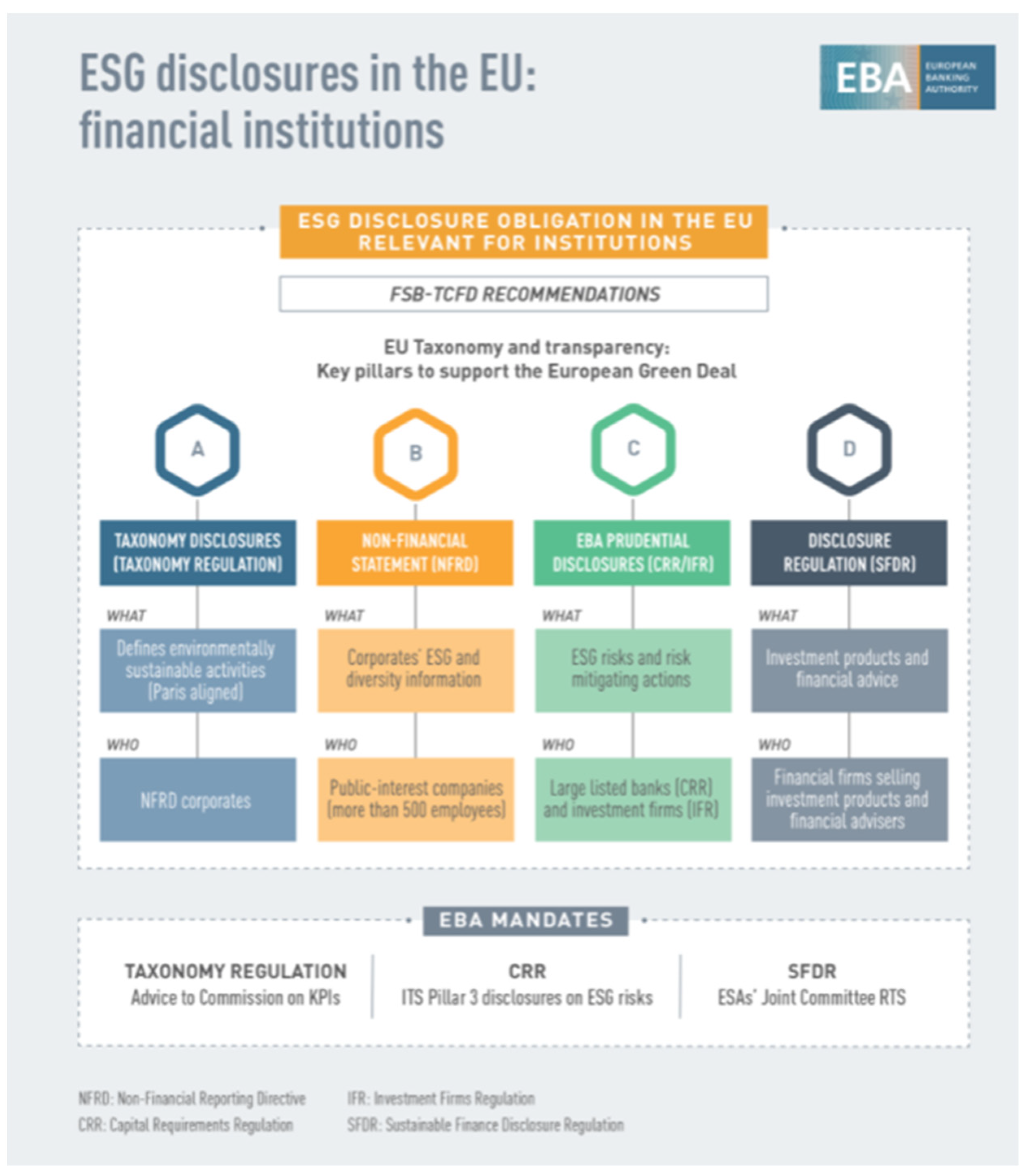

Figure 1 summarises the disclosure requirements for banks under the current European regulatory framework.

As shown in

Figure 1, the Taxonomy Regulation, that came into force in 2020, introduces some criteria for the classification of the activities performed by industrial companies based on their environmental sustainability (in line with the provisions of the Paris Climate Agreement). The definition of specific criteria for the classification of the activities performed by industrial companies provides more clarity regarding the environmental sustainability of the firms’ businesses.

The Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) imposes additional disclosure requirements on listed industrial companies with more than 500 employees. The aim of this directive is to improve the quality of data available to banks and investors to direct financial resources toward sustainable investments.

Furthermore, following the introduction of the so-called CRR2 (i.e., Capital Requirements Regulation) the European significant banks are expected to disclose in the information provided to investors the risks related to ESG factors to which they are exposed, and the related mitigating actions being undertaken to reduce their severity.

Finally, in 2021, the Financial Services Sustainability Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) also came into force. This regulation introduces a new set of rules that is aimed at making the sustainability profile of funds and financial products more comparable and easier for investors to understand. The new rules will lead to the classification of financial products in specific types by including metrics to assess their environmental, social and governance (ESG) impacts.

It has also been noticed that the EBA has been given three specific mandates to further enforce the introduction of the ESG principles in the European banking regulation. Under the taxonomy regulation, the EBA has been requested to propose to the European Commission a number of key performance indicators (KPIs), together with the related methodology for the disclosure by credit institutions and by investment firms, on how and to what extent their activities qualify as environmentally sustainable. In its opinion released in March 2021 [

22], the EBA underlined the importance of the green asset ratio (GAR) as a key means to understand how institutions are financing sustainable activities and meeting the Paris agreement targets.

In March 2021, the EBA also published a consultation paper on draft implementing technical standard (ITS) [

23] on Pillar 3 disclosures on environmental, social and governance risks as a response to the second mandate highlighted in

Figure 1. In line with the requirements laid down in the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), the draft ITS proposes comparable quantitative disclosures on climate-change related transition and physical risks, including information on exposures towards carbon related assets and assets subject to chronic and acute climate change events. They also include quantitative disclosures on institutions’ mitigating actions supporting their counterparties in the transition to a carbon neutral economy and in the adaptation to climate change. In addition, they request significant banks to disclose their GAR. The green asset GAR identifies the institutions’ assets financing activities that are environmentally sustainable according to the EU taxonomy, such as those consistent with the European Green Deal and the Paris agreement goals. Finally, the draft ITS provides qualitative information on how institutions are embedding ESG considerations in their governance, business model and strategy and risk management framework.

The new banking regulation package, CRR2 and CRDV (i.e., Capital Requirements Directive), has also provided a number of mandates to the European Banking Authority (EBA) to issue specific regulations and guidelines for banks and supervisory authorities with regards to the sustainable finance.

Figure 2 summarises the main mandates that have been provided to the EBA through the new banking regulatory package.

The first mandate (also mentioned in

Figure 1), stemming from the introduction of the SFDR, that was given to the European Banking Authority (EBA) and the other two authorities that are part of the European Supervisory Authorities (ESMA and EIOPA) led to the introduction of a binding technical standard that provides detailed indications on how financial investors must communicate the potential negative impacts of their investment choices (through the disclosure of specific indicators) on sustainability factors [

25]. Furthermore, the technical standard also provides detailed indications on the pre-contractual information on sustainability issues to be provided when placing financial products on the market.

The second mandate entrusts the EBA with the task of exploring the possibility of introducing ESG risk factors within the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) and the regulatory stress tests.

Indeed, the EBA sees a need to strengthen institutions’ integration of ESG risks into their business objectives and procedures, as well as to include ESG risks appropriately into their internal governance frameworks. Adapting an institution’s business plan to include ESG risks as drivers of prudential risks might be regarded as a progressive risk management method for mitigating the potential impact of ESG risks. Additionally, the EBA sees a need to gradually develop methodology and approaches for conducting a climate risk stress test, while taking methodological and data constraints into account. The purpose of a climate risk stress test should be to inform institutions about their own business models and investment strategies’ resilience. However, supervisors’ current assessment of credit institutions under the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) may not be sufficient to enable them to comprehend the longer-term impact of ESG risks, their breadth and magnitude, on future financial positions and associated long-term vulnerabilities. In this context, the EBA believes that a new area of analysis should be added to supervisory assessment: determining whether credit institutions adequately test the long-term resilience of their business models against the time horizons of relevant public policies or broader transition trends, i.e., beyond commonly used timeframes of 3–5 years or potentially even the 10-year horizon already applied in some jurisdictions [

26].

Finally, another mandate requires the EBA to support the work of the group of experts (set up by the European Commission) on sustainable finance. EBA is expected to provide its technical support on issues, such as the update of the taxonomy of sustainable assets, the definition of binding standards for the identification of so-called “Green Bonds” and the issuance of guidelines on the disclosure of information relating to climate risk.

In addition to the mandates specifically received by the European Commission, the EBA has recently updated its guidelines on loan origination and monitoring targeted to banks [

27]. In these guidelines, it is explicitly requested that banks incorporate ESG risk factors in the definition of their credit risk appetite and in their credit risk management practices.

Furthermore, the Single Supervisory Mechanism (European Central Bank), the supervisory authority of the significant banks of the 19 Eurozone countries, has issued its own guide on climate and environmental risks in which it sets out the expectations with regard to the management of such risks and the related disclosure to investors [

28]. The table below (

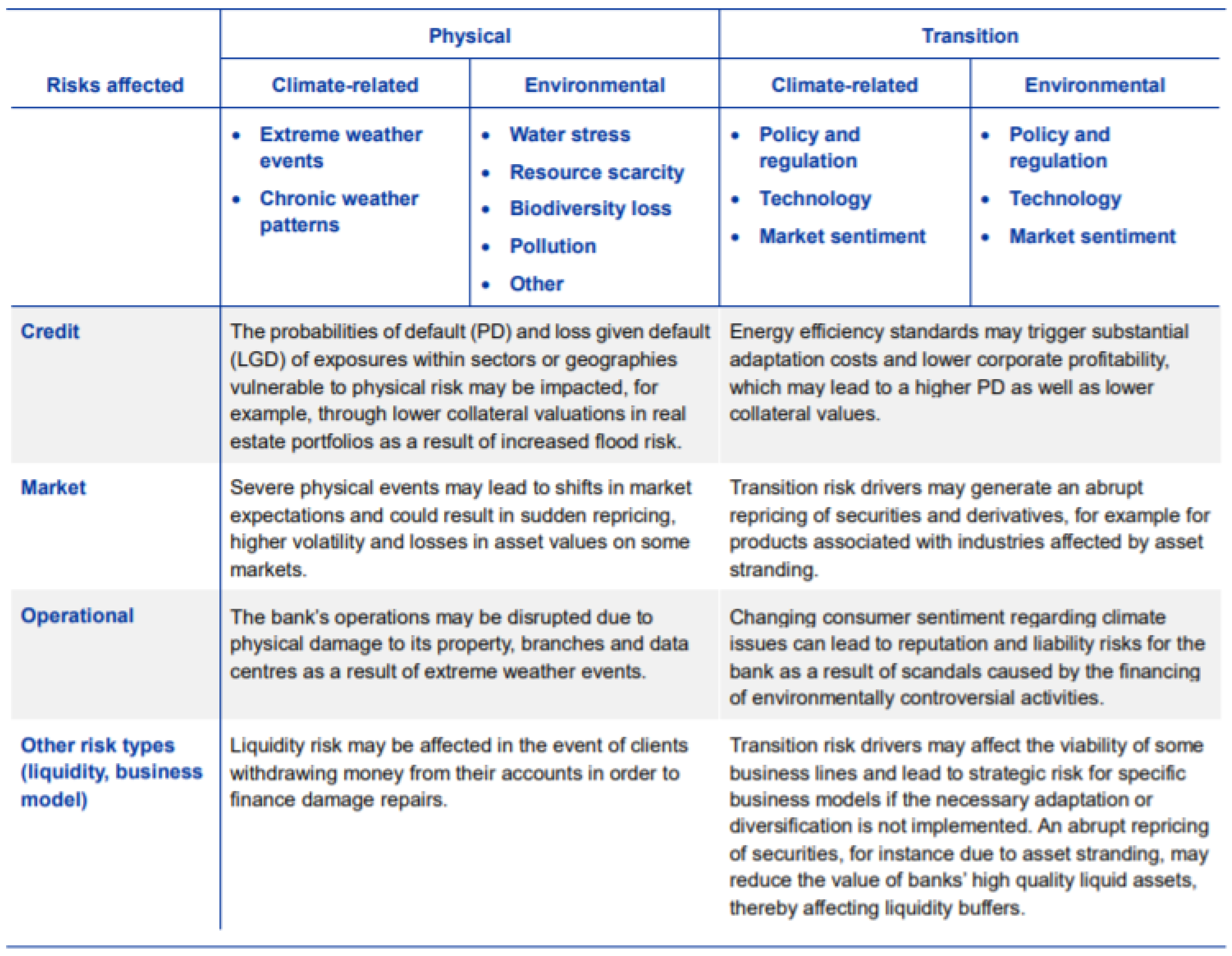

Figure 3) shows the main impacts on the various risk categories highlighted in the guide issued by the European Central Bank.

As reported in the table above, the credit risk area might be negatively impacted by the physical risk through the lower collateral valuations in real estate portfolios in areas that are highly exposed to flood risk. This, in turn, may negatively affect the PDs and LGDs of these portfolios. Similarly, severe climate events might lead to shifts in the market sentiment that could trigger a market crash. Extreme climate events might also have a negative impact on operational risk as they could entail physical damages to the credit institutions’ premises and properties causing disruptions in the provision of services.

Moreover, the EBA recognizes that the qualitative and quantitative indicators, metrics, and procedures available to institutions for risk assessment may be more sophisticated for environmental hazards than for social and governance concerns. Thus, institutional management of ESG risks, as well as the incorporation of ESG risks into monitoring, may first prioritize environmental issues. Nonetheless, developments in this policy area, especially the further development of the EU Taxonomy Regulation, will progressively enable institutions and regulators to use and incorporate social and governance indicators into the management and supervision of ESG risks [

26].

4. Comparing and Contrasting National Level Regulations for Banking Institutions

The introduction of the abovementioned regulations should help in ensuring consistency for the disclosure practices of banks and financial intermediaries across the EU. In fact, the European national legal obligations on environmental, social and governance disclosures are generally incoherent [

29].

All the European countries do not have specific prudential regulatory requirements to request financial intermediaries to consider ESG factors in their business practices (

Table 1). The absence of such requirements is mainly attributable to the lack of a common definition of ESG factors. In this respect, it is worth noticing that the academic literature has observed that the ESG scores assigned to the major listed companies in the euro area by three of the main providers vary significantly for the same firm, while the correlation between the more traditional credit ratings is over 90 per cent [

30]. With reference to the disclosure requirements, the practices across the EU vary widely with jurisdictions that have more stringent disclosure requirements than others.

Countries such as France, Denmark, and Italy require all classes of investors, including banks, mutual funds, insurance firms and asset managers, to disclose their holdings. Even if this first group of countries requires the disclosure of the holdings from all investors, they still have different requirements and practices for disclosing this information to the market. This, in turn, determines different disclosure conventions followed by the investors operating in these countries. Furthermore, it has to be noticed that investors do not have legal requirements requesting them to disclose any specific information on ESG.

A second group of countries has specific requirements in place only for certain classes of investors. On one hand, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom have legal obligations requiring pension funds (which typically have long-term investment horizons) to disclose their holding to the market. This group of countries does not have additional legal obligations with regards to the disclosures of ESG factors required from investors. On the other hand, even if in absence of a specific requirement entailing the disclosure of the holdings, Belgium requires only asset managers (but not the other investors) to explain how ESG considerations are factored into their investment strategy.

A third group of countries, including Austria, Luxembourg, Portugal and Sweden impose no legal obligations on disclosure on institutional investors or fund managers nor specific requirements related to ESG factors.

Against this background, it is important to notice that notwithstanding the absence of specific national requirements, the IORP II Directive allows member states to ensure that entities subject to the directive report the importance and materiality of ESG factors. The deadline for the transposition of this directive into the national regulations was January 2019 and not all member states fully transposed the provisions included in it. As a consequence, the practices followed by the EU countries are still divergent. After Brexit, the UK does not have to adhere to the European regulatory framework any longer. However, in 2019 it published its “Green Finance Strategy” in which it pledged, among other things, to follow the ambitions of the EU’s action plan. Despite the claims made by the UK government, it still lacks a sustainable finance regulatory taxonomy (already available in the EU) [

31] and most probably will not endorse similar regulations as those endorsed by the EU Commission.

The initiatives launched at a European level (see

Section 3) will therefore ensure a consistent treatment of the ESG factors by the European financial intermediaries and will provide more clarity on what should be understood as ESG compliance, leading the way to the collection of reliable data in this area.

5. Conclusions

In recent years, European policy makers have ramped up their efforts to create a regulatory framework for banks that encompasses ESG principles.

This paper presents patterns, gaps and reflections on the evolution of European policies published in recent years on Environmental, Social, and Governance issues for financial intermediaries supporting the view of a need for strengthening the awareness on these aspects in the future. We surveyed the official European legislative documents issued on ESG, to offer a complete overview of the state of art of the policy framework on this topic. Moreover, we contrasted and compared policies issued at a national level, to provide new insights for policy makers around Europe for improving the existing framework in each European country. However, this paper does not consider the ESG policies implemented in countries outside the European Union.

The main efforts have been devoted to enhancing the disclosure requirements for banks, financial intermediaries and industrial companies alike. The main initiatives that are worth mentioning are: (i) the taxonomy regulation, that introduces specific criteria for the classification of the activities performed by industrial companies; (ii) the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) that imposes additional reporting requirements for listed companies having more than 500 employees to facilitate the comparability of the information provided to financial investors; (iii) the CRR2 that requires European banks to disclose the ESG risks to which they are exposed to as well as the remedial actions undertaken to reduce the severity of these risks and (iv) the Financial Services Sustainability Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) aimed at making the sustainability profile of funds more comparable and easy to understand for financial investors.

All these initiatives have been beneficial given that the disclosure requirements at a national level have been quite diverging [

32]. Moreover, through the introduction of clearer criteria for the classification of the activities performed by industrial companies, they set the stage for the introduction of more specific guidelines and regulations. The mandates given to the EBA by the new banking regulatory package (CRR2 and CRDV) are explicitly aimed at introducing the ESG principles in the regulatory framework for banks. Other relevant initiatives in this respect are the introduction of these principles in the EBA guidelines on loan origination and monitoring for banks and the SSM guide on climate risk targeted at the significant banks of the Eurozone countries.

In line with the academic and institutional debate on ESG in finance, we support the need for improving the level of awareness about ESG, sharing the view that the financial system can act as a catalyst for the transition to a more sustainable economy as a whole. Future works could leverage this policy review to assess the efficacy of the policies implemented in Europe with regards to the ESG principles. Furthermore, future works might contribute to the discussion by enlarging the scope of the analysis and including the regulatory framework of countries outside the EU.