A Model for Measuring and Managing the Impact of Design on the Organization: Insights from Four Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

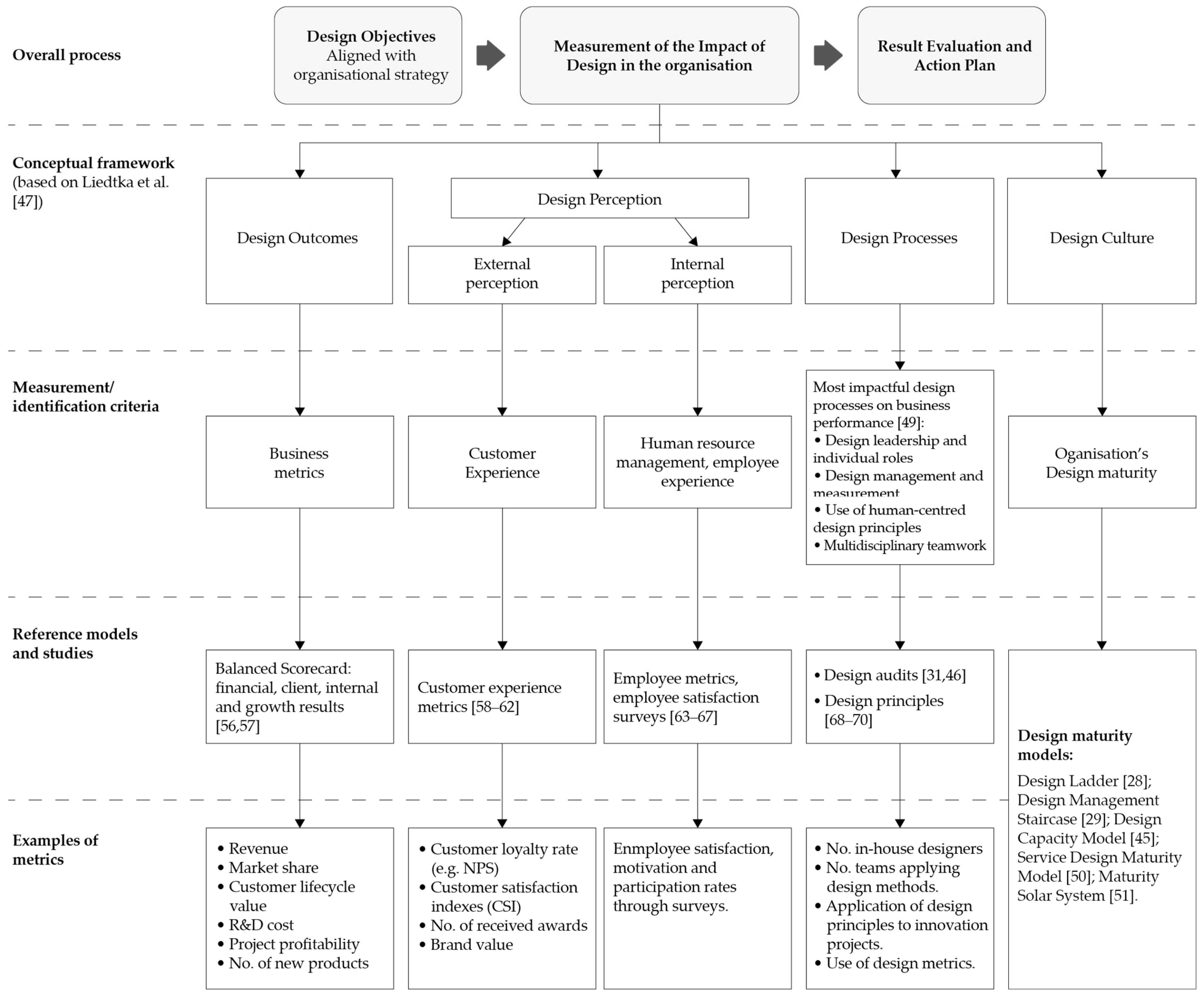

2. The Impact of Design on the Organization

- In the first place, we identify the changes in people’s perception of the company. It is reasonable to assert that a higher likelihood of customer recommendation will positively impact sales, just as higher employee satisfaction will imply a higher quality of service. At this level, the changes are still measurable—e.g., through satisfaction questionnaires—although the type of information collected is far from the traditional economic/financial indicators and is closer to emotional aspects such as satisfaction, loyalty, brand perception, motivation, etc.

- Secondly, there are changes in the conversations between people in the organization, for example, companies that spend time discussing customer experience or leaders who encourage their teams to experiment and take risks. These changes are reflected more clearly in design processes, such as an increase in the number of designers on staff, the systematization of design processes, or the use of indicators to manage the customer experience, among others.

- Thirdly and finally, the integration of design in the company entails changes in the individual mindsets of staff members and, consequently, in the organizational culture, understood as the aggregation of these mindsets. Liedtka et al. [47] explained it with the example of a management team in a financial company that started to think about customers in a more empathetic way, and a food chain that made kitchen staff feel like “chefs”.

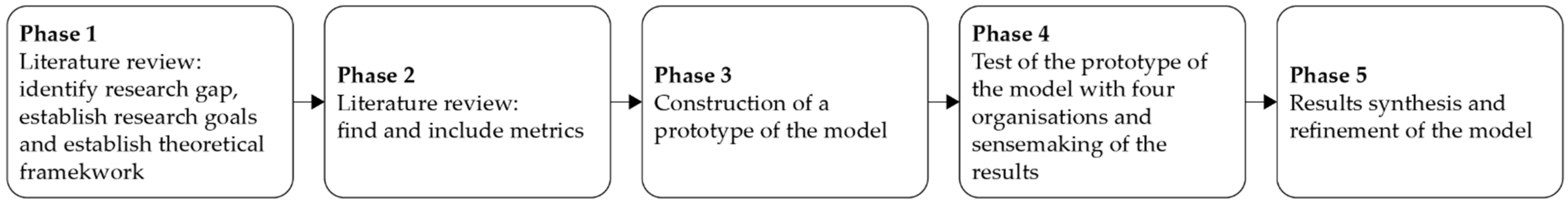

3. Methodology

- Contcen is a medium-sized company dedicated to providing contact center and customer care solutions. The company was recently introduced to human-centered design by one of its major clients. The latter showed the company a project developed in collaboration with the author’s university in which an innovative service concept was developed. The ability to come up with creative and differentiating value propositions through design aroused great interest in Contcen’s management. Since then, the company has been working on redesigning and optimizing its processes based on its own design methods, which are now a differentiator of its services.

- FoodCollective is a business group with more than 11,000 employees and is a national leader in industrial catering. It offers catering and cleaning services for schools, nursing homes, hospitals, and companies. However, its experience with design is focused on the catering division for schools in the north of Spain. A local competitor surprised FoodCollective with a disruptive design-based value proposition using participatory processes to create new school canteen services. FoodCollective reacted by hiring a designer and external consultants to develop a new service, based on user research and participatory design processes, that would give it a competitive advantage over its competitors. As a result, FoodCollective used design to capture each facility’s particular needs and generate tailored dining experiences. Having realized the potential value of design for the company, today FoodCollective remains committed to building design capabilities to continuously improve its innovation processes.

- Bankop is a credit union renowned locally for its customer orientation. Despite its status as a large organization, it is a small player in a sector led by gigantic multinationals. While the company has deemed the customer experience to be a key aspect of its frontline services for years, it has had little presence in internal processes such as innovation. Nevertheless, market demand and competitor moves led Bankop to position customer experience as one of the main goals of its latest strategic plan. The company thus developed its own methodology based on the principles and methods of design for the development of services with a human-centered focus, so as to respond to the current societal needs. A recently formed four-member team, namely the Customer and Service Development team, was trained in human-centered design to take responsibility for implementing the new methodology. The team had already applied it in the design of a new mortgage service, although it is still in the implementation stage.

- Propind is the fourth participating organization, a small consultancy office specializing in industrial property (IP) services. The relationship of the company with design started with the need for differentiating themselves from low-cost competitors. They found the opportunity to add value to their service offering by moving from transactional to relational interactions with clients, to assist them in the strategic management of IP assets. Some Propind members participated in the design of the new strategic IP services, which were led by outsourced designers. Even though the company develops new services sporadically, first-hand experience with the design process generated an awareness of some design methods and tools that Propind could use to capture customer insights, continuously improve their services, and enhance strategic decision-making in their routine work.

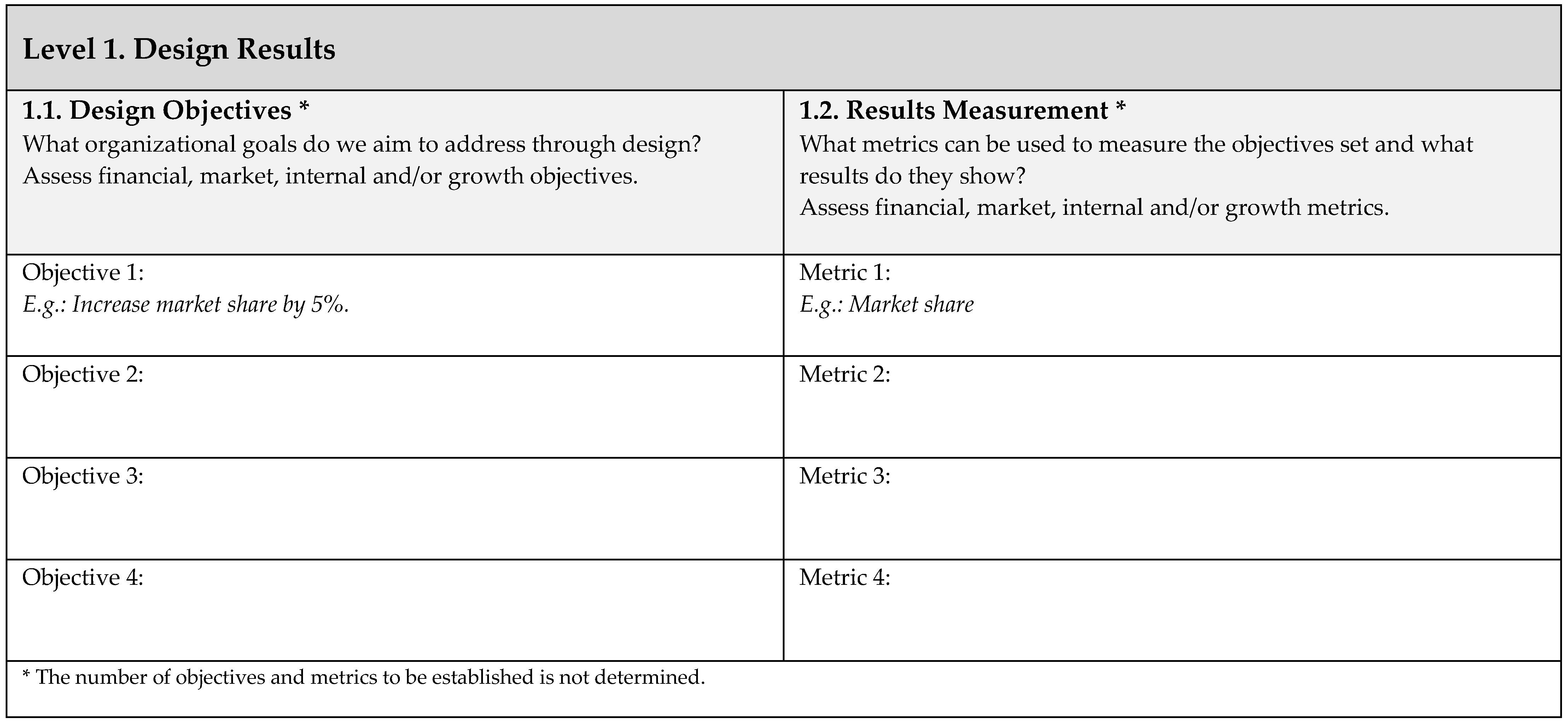

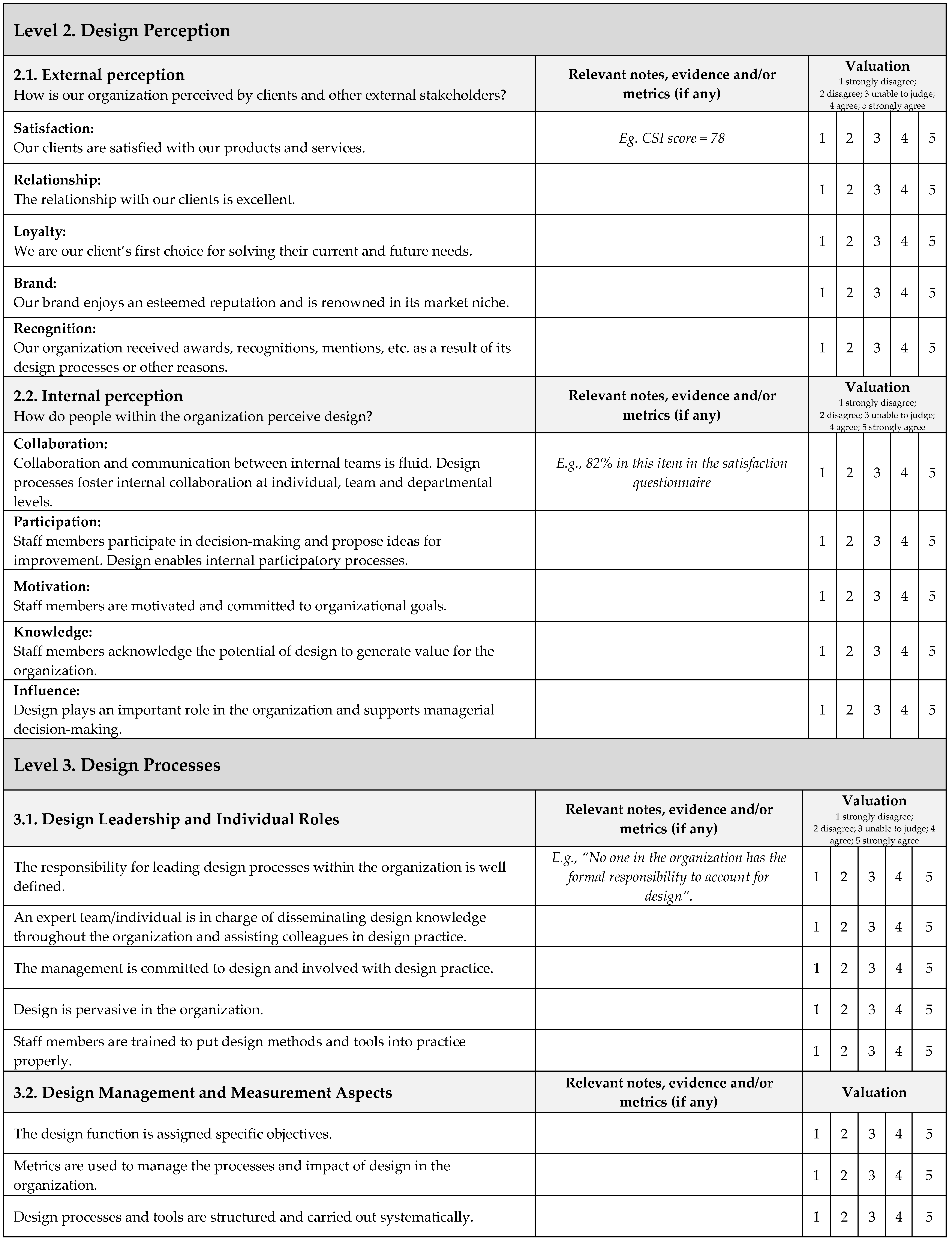

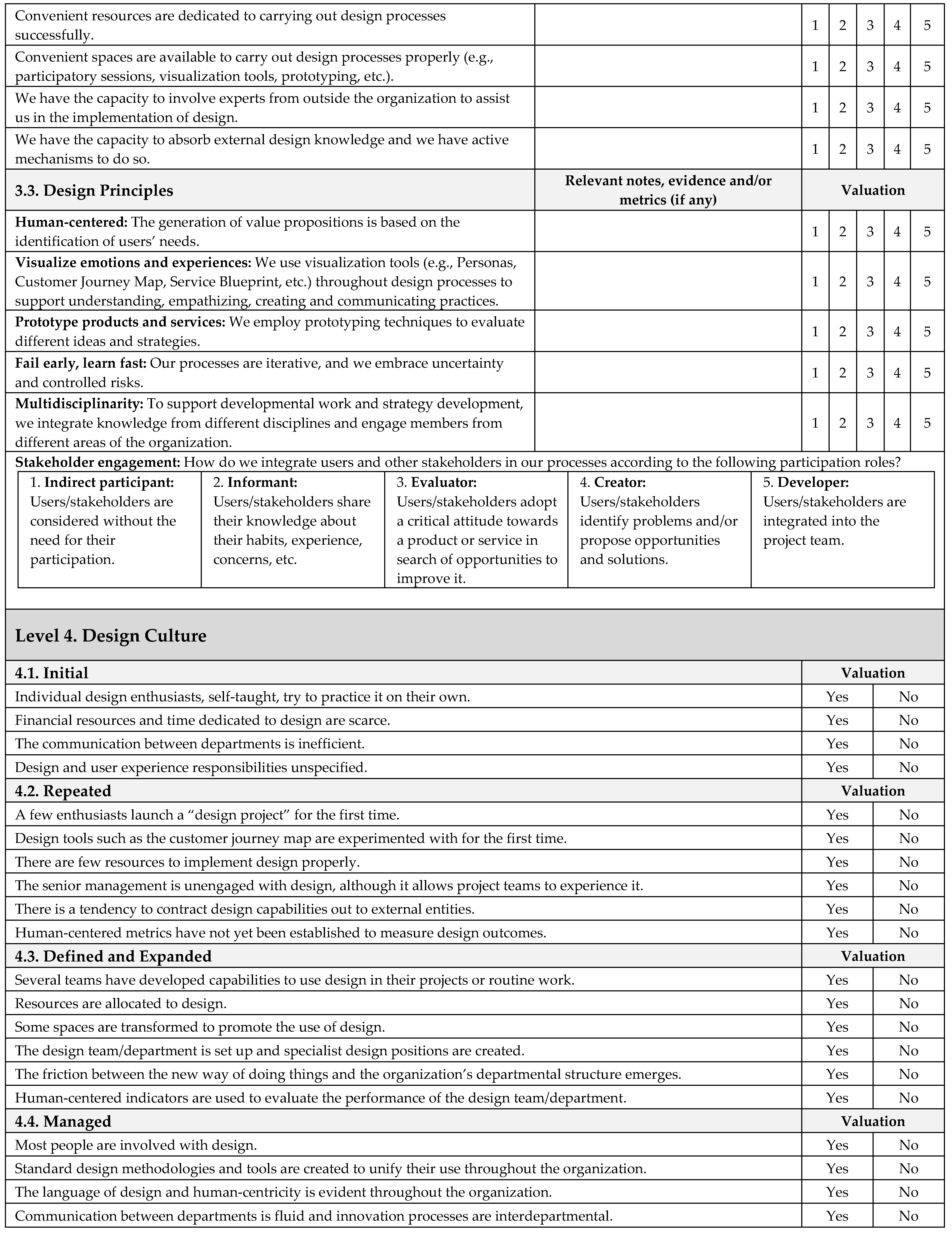

4. Design Impact Measurement and Management (DIMM) Model

5. Experimentation with the Model

5.1. Contcen

- Design results. Although it was too early to obtain quantifiable results from the integration of design when the test was conducted, the company foresaw benefits in the medium term. They were convinced that the agility they gained in execution times would soon achieve higher profitability per project and they would be able to capture a larger market share. In addition, as the company was proactive in configuring their offer, it revealed to customers their own needs through a prior diagnosis. As a result, it was able to prescribe more comprehensive services that resulted in higher turnover.

- Design perception. The company perceived that customer satisfaction increased, as some clients asserted that they were “impressed” with the new way of working. The company claimed that customer loyalty improved and that the hours spent with customers increased significantly. Internally, participation and collaboration between people also increased; “the method itself makes people participate more,” as said by the Director of Projects and Technology.

- Design processes. The company hired two people to form a design team. These two people led the design processes, but 11 other people received specific UX training, and an increasing number of employees were getting involved in projects using the new methods. Regarding capturing customer needs, the Director of Projects and Technology explained that “now, much more information is collected”. They also progressed in the use of digital prototypes to streamline their processes and minimize development errors. At the same time, they pointed out that they kept improving their working methods and were considering augmenting the use of visualization tools and the integration of end-users in design processes. However, the design team had not yet been assigned specific objectives and performance indicators.

- Design culture. The people interviewed considered that design was defined and expanded in the company. They ensured that everyone was, to some extent, committed to design, as all projects were approached from a design perspective. However, the new culture was recent and not yet consolidated, which created some chaos at work. They felt energized to take on the challenge and were confident that the experience would enable them to become more efficient with the new processes. Specifically, they defined three priority areas for improvement: internal communication, the involvement of end-users, and the redesign of certain deliverables for refining the new work methodology. Furthermore, they were exploring metrics to manage their design processes, to continuously improve their capabilities.

5.2. Food Collective

- Design results. Interviewees foresaw improvements in the medium term. Due to the nature of their market, “we are now investing to reap the rewards,” the Sales Manager indicated. However, he pointed out that design was helping them to build customer loyalty and that the reception of the new service was good, so they were optimistic about obtaining economic benefits “in one or two years”.

- Design perception. The launch of the Borbor service contributed to customers’ perception of the company, they said, despite not yet having the annual results of the NPS or loyalty indicators. The new service reflected a more forward-looking working method and encouraged closer collaboration with clients and users. They also pointed out that “the collaboration with the university to develop the new service underpinned the image of the service itself”. Besides, they claimed that the people working at FoodCollective were motivated by the new approach and working procedures.

- Design processes. The company decided to hire a designer, as the skills required to deliver the Borbor service were new to FoodCollective. Other people were occasionally involved in the design process but had not received specific design training. They also claimed that “users’ active participation increased” in the innovation processes. The working methodology around the Borbor service improved with respect to the use of visualization tools and the launch of pilot services. However, the design activity at FoodCollective remained formally unmanaged and located only in the organizational area in charge of the new service.

- Design culture. Respondents considered design in FoodCollective to be “repeated”, referring to the scale used in the model to measure design maturity. There was a person dedicated to design processes, and there was a defined method to carry out such processes. They pointed out that the next step required scaling up design within the organization, for example, by hiring or training others to lead design processes, using design in other projects, and establishing design processes at the organizational level. They stressed the need to succeed in existing projects to gain management’s backing and to devote more effort and resources to design activities.

5.3. Bankop

- Design results. The company regarded the development of customer experience capabilities as a long-term commitment. Therefore, they did not envisage any impact on the market by the time the interview was conducted, and no market indicators could be measured. “If everyone is supporting us [it] is because they know that it will have an impact in the long term, but we don’t have the capacity to measure it yet,” explained one of the Customer and Service Development Technicians. However, during the training project, the team designed a new mortgage service that was already in the implementation phase, so the effects on the market were expected to become visible soon after.

- Design perception. The services resulting from design projects had not yet been launched onto the market, so the impact of design remained within the organizational boundaries. However, the internal dissemination of results was outstanding and raised organization-wide commitment to design, including among the senior management.

- Design processes. New service development processes underwent significant changes. New organizational structures were formed, including the creation of the new Customer and Service Development team and the recruitment of a designer. In addition, the team developed a working methodology nurtured by human-centered design methods and principles, which they planned to follow systematically in future projects. One of the technicians explained that “this is a new mindset, a methodology and a tool that will be implemented from now on. What we once thought now has form and structure”.

- Design culture. Design practices were incipient, but they had a solid base thanks to the development of the new work methodology and the support of the senior management. The widespread dissemination of early results generated interest in other areas of the organization, so the forthcoming challenge for the Customer and Service Development team was to engage other departments in design projects to scale up design capabilities throughout the organization.

5.4. Propind

- Design results. Propind trusted in design as a method for confirming certain hunches about market needs and responding to them with a differentiating service offering, one that would expand the client base and increase the turnover. Therefore, a direct result of the design project was the launch of two new, advanced IP management services. Although pilot projects were still to be implemented, Propind members were optimistic because they had received positive feedback from their clients and the backing of local business associations. In view of the encouraging results, the company was considering continuing to develop some skills, to improve the capture of market insights and innovation through design methods.

- Design perception. The shift from a transactional to a relational service model was expected to enhance client loyalty. In addition, Propind learned to use design research methods (e.g., conducting semi-structured interviews and synthesizing insights into customer personas) to get closer to customers, understand their needs and reduce the gap between customer expectations and the service provided. Internally, they also incorporated visualization tools that supported team communication and decision-making.

- Design processes. Propind members who participated in the design project developed basic design skills and learned methods to improve team decision-making, customer orientation and visual thinking. However, the capacities acquired so far were not considered sufficient to address design projects autonomously. If Propind launched a new design project, it would need the assistance of external designers again to carry out those processes requiring more advanced design capabilities.

- Design culture. Design was nascent at Propind. That first interaction with design caused Propind to understand how design brought value to their business. As design was not central to the organization’s routine work, its design maturity was expected to grow slowly. Nevertheless, the company was open to developing some progress in design methods—e.g., facilitating co-creation workshops with clients and capturing and visualizing customer needs. “Emotional aspects are key in a multitude of circumstances, so we will certainly use these tools in future activities”, the Managing Director indicated.

6. Critical Evaluation of the Model

6.1. The DIMM Model as an Assessment Tool

6.2. The DIMM Model as a Reflective Tool

6.3. The DIMM Model as a Strategizing Tool

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moore, M.L.; Tjornbo, O.; Enfors, E.; Knapp, C.; Hodbod, J.; Baggio, J.A.; Norström, A.; Olsson, P.; Biggs, D. Studying the complexity of change: Toward an analytical framework for understanding deliberate social-ecological transformations. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.; Thomas, S.; Rosano, M. Using industrial ecology and strategic management concepts to pursue the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saynisch, M. Mastering Complexity and Changes in Projects, Economy, and Society via Project Management Second Order (PM-2). Proj. Manag. J. 2010, 41, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, T.; Davies, A.; Nightingale, P. Dealing with uncertainty in complex projects: Revisiting Klein and Meckling. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2012, 5, 718–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, P.W.G. Reconstructing Project Management; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 7, ISBN 9780470659076. [Google Scholar]

- Hölzle, K.; Rhinow, H. The Dilemmas of Design Thinking in Innovation Projects. Proj. Manag. J. 2019, 50, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud-Jouini, S.B.; Midler, C.; Silberzahn, P. Contributions of Design Thinking to Project Management in an Innovation Context. Proj. Manag. J. 2016, 47, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, D.; Martin, R.L. Design Thinking and How It Will Change Management Education: An Interview and Discussion. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2006, 5, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, B. Design thinking: Organizational learning in VUCA environments. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grenha Teixeira, J.; Patrício, L.; Huang, K.H.; Fisk, R.P.; Nóbrega, L.; Constantine, L. The MINDS Method: Integrating Management and Interaction Design Perspectives for Service Design. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, T. Design Thinking: Integrating Innovation, Customer Experience, and Brand Value; Allworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-58115-668-3. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, N.; Patrício, L.; Morelli, N.; Magee, C.L. Bringing Service Design to manufacturing companies: Integrating PSS and Service Design approaches. Des. Stud. 2018, 55, 112–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloppen, J.; Fjuk, A.; Clatworthy, S. The role of service design leadership in creating added customer value. In Innovating for Trust; Lüders, M., Andreassen, T.W., Clatworthy, S., Hillestad, T., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northhampton, UK, 2017; pp. 230–244. [Google Scholar]

- Iriarte, I.; Hoveskog, M.; Justel, D.; Val, E.; Halila, F. Service design visualization tools for supporting servitization in a machine tool manufacturer. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 71, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, N.; Götzen, A.; de Simeone, L. Service Design Capabilities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-56281-6. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, E.; Sangiorgi, D. Service Design as an Approach to Implement the Value Cocreation Perspective in New Service Development. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 21, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bont, C.; Xihui Liu, S. Breakthrough Innovation through Design Education: Perspectives of Design-Led Innovators. Des. Issues 2017, 29, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, D. Implementing design thinking in organizations: An exploratory study. J. Organ. Des. 2018, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, A.L.; Bitner, M.J.; Brown, S.W.; Burkhard, K.A.; Goul, M.; Smith-Daniels, V.; Demirkan, H.; Rabinovich, E. Moving forward and making a difference: Research priorities for the science of service. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 4–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbach, K.D.; Stigliani, I. Design Thinking and Organizational Culture: A Review and Framework for Future Research. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2274–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, R. Aftermarkets the Messy Yet Refined Logic of Design. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2010, 37, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Price, R.; Wrigley, C.; Matthews, J. Action researcher to design innovation catalyst: Building design capability from within. Action Res. 2018, 19, 318–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinkenaite, I.; Breunig, K.J.; Fjuk, A. Capable Design or Designing Capabilities? An Exploration of Service Design as An Emerging Organizational Capability in Telenor. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2017, 13, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mutanen, U.M. Developing organisational design capability in a Finland-based engineering corporation: The case of Metso. Des. Stud. 2008, 29, 500–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aricò, M. Service Design as a Transformative Force: Introduction and Adoption in an Organizational Context. Ph.D. Thesis, Copenhagen Business School, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtmollaiev, S.; Fjuk, A.; Pedersen, P.E.; Clatworthy, S.; Kvale, K. Organizational Transformation Through Service Design: The Institutional Logics Perspective. J. Serv. Res. 2018, 21, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoni, P.; Dell’Era, C.; Ferraloro, G.; Peradotto, M.; Karlsson, H.; Verganti, R. Design Contribution to the Competitive Performance of SMEs: The Role of Design Innovation Capabilities. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2016, 25, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlau, U.H. In Denmark, Design Tops the Agenda. Des. Manag. Rev. 2004, 15, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kootstra, G.L. The Incorporation of Design Management in Today’s Business Practices. An Analysis of Design Management Practices; Inholland University of Applied Sciences: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Westcott, M.; Sato, S.; Mrazek, D.; Wallace, R.; Vanka, S.; Hardin, D. The DMI Design Value Scorecard: A new Design Measurement and Management Model. Des. Manag. Inst. J. 2014, 24, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloğlu, F.; Er, Ö. Discussing a New Direction for Design Management through a New Design Management Audit Framework. Des. J. 2017, 20, S502–S521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Borja De Mozota, B. Design and competitive edge: A model for design management excellence in European SMEs. Des. Manag. J. 2002, 2, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmberg, L. Building Design Capability in the Public Sector. Expanding the Horizons of Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liedtka, J. Evaluating the impact of design thinking in action. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management Proceedings, Atlanta, GA, USA, 4–8 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Relich, M.; Nielsen, I.; Bocewicz, G.; Smutnicki, C.; Banaszak, Z. Declarative modelling approach for new product development. IFAC-Pap. 2020, 53, 10525–10530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relich, M.; Świć, A.; Gola, A. A knowledge-based approach to product concept screening. In Proceedings of the Distributed Computing and Artificial Intelligence, 12th International Conference, Salamanca, Spain, 3–5 June 2015; pp. 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Relich, M. A knowledge management system for evaluating the potential of a new product. In Proceedings of the 21st European Conference on Knowledge Management, Coventry, UK, 3–4 September 2020; pp. 668–676. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, B. Validating a Design Thinking Strategy: Merging Design Thinking and Absorptive Capacity to Build a Dynamic Capability and Competitive Advantage. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 6, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistretti, S. Framing the microfoundations of design thinking as a dynamic capability for innovation: Reconciling theory and practice. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrík, V.; Gregor, M.; Grznár, P.; Mozol, Š.; Schickerle, M.; Ďurica, L.; Marschall, M.; Bielik, T. Design of manufacturing lines using the reconfigurability principle. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, L.; Ragai, I.; Wang, L. New trends in Manufacturing Systems Research 2020. J. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 56, 585–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gola, A.; Pastuszak, Z.; Relich, M.; Sobaszek, Ł.; Szwarc, E. Scalability analysis of selected structures of a reconfigurable manufacturing system taking into account a reduction in machine tools reliability. Maint. Reliab. 2021, 23, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Innobarometer 2016—EU Business Innovation Trends Fieldwork; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Design Council. The Design Economy 2018: The state of Design in the UK; Design Council: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Storvang, P.; Jensen, S.; Christensen, P.R. Innovation through Design: A Framework for Design Capacity in a Danish Context. Des. Manag. J. 2014, 9, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moultrie, J.; Clarkson, P.J.; Probert, D. A tool to evaluate design performance in SMEs. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2006, 55, 184–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedtka, J.; King, A.; Bennett, K. Solving Problems with Design Thinking: Ten Stories of What Works; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-231-16356-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hands, D. Design Transformations: Measuring the Value of Design. In The Handbook of Design Management; Cooper, R., Junginger, S., Lockwood, T., Eds.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2011; pp. 366–378. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey The Business Value of Design; McKinsey & Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018.

- Corsten, N.; Prick, J. The Service Design Maturity Model. Touchpoint. Serv. Des. J. 2019, 10, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- InVision. The New Design Frontier Astronomical Impact. 2019. Available online: https://www.invisionapp.com/design-better/design-maturity-model/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Romme, A.G.L.; Dimov, D. Mixing oil with water: Framing and theorizing in management research informed by design science. Designs 2021, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romme, A.G.L.; Reymen, I.M.M.J. Entrepreneurship at the interface of design and science: Toward an inclusive framework. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2018, 10, e00094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketokivi, M.; Hameri, A. Bridging Practice and Theory: A Design Science Approach. Decis. Sci. 2009, 40, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acklin, C. Design management absorption model: A framework to describe and measure the absorption process of design knowledge by SMEs with little or no prior design experience. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2013, 22, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Putting the Balanced Scorecard to Work. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Focusing Your Organization on Strategy—With the Balanced Scorecard. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R.; Aagja, J.; Bagdare, S. Customer experience—A review and research agenda. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 642–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.V.; Hult, G.T.M.; Mithas, S.; Keiningham, T.; Fornell, C. Turning Complaining Customers into Loyal Customers: Moderators of the Complaint Handling–Customer Loyalty Relationship. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiningham, T.L.; Aksoy, L.; Cooil, B.; Andreassen, T.W. Linking Customer Loyalty to Growth. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2008, 49, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Keiningham, T.L.; Cooil, B.; Aksoy, L.; Andreassen, T.W.; Weiner, J. The value of different customer satisfaction and loyalty metrics in predicting customer retention, recommendation, and share-of-wallet. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2007, 17, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Johnson, M.D.; Anderson, E.W.; Cha, J.; Bryant, B.E. The American Customer Satisfaction Index: Nature, Purpose, and Findings. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Voorhees, C.M.; Brusco, M.J. Service Sweethearting: Its Antecedents and Customer. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Gursoy, D. Employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and financial performance: An empirical examination. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larivière, B.; Bowen, D.; Andreassen, T.W.; Kunz, W.; Sirianni, N.J.; Voss, C.; Wünderlich, N.V.; De Keyser, A. “Service Encounter 2.0”: An investigation into the roles of technology, employees and customers. J. Ofbus. Res. 2017, 79, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Renzl, B. The relationship between interpersonal trust, employee satisfaction, and employee loyalty. Total Qual. Manag. 2006, 17, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranburu, E.; Lasa, G.; Gerrikagoitia, J.K.; Mazmela, M. Case Study of the Experience Capturer Evaluation Tool in the Design Process of an Industrial HMI. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpen, I.; Gemser, G.; Calabretta, G. A multilevel consideration of service design conditions: Towards a portfolio of organisational capabilities, interactive practices and individual abilities. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, L.; Gustafsson, A.; Fisk, R. Upframing Service Design and Innovation for Research Impact. J. Serv. Res. 2018, 21, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickdorn, M.; Lawrence, A.; Hormness, M.; Schneider, J. This Is Service Design Doing, 2nd ed.; O’Reilly: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-491-92718-2. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, R.F.; Mourgues, C.; Alarcón, L.F.; Pellicer, E. An Assessment of Lean Design Management Practices in Construction Projects. Sustainability 2020, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ortiz, J. Sustainable business modeling: The need for innovative design thinking. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, H.; Ketchie, A.; Nehe, M. The integration of Design Thinking and Strategic Sustainable. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, R.; Maher, M.; Mann, S.; Mcalpine, C.A. Integrating design thinking with sustainability science: A Research through Design approach. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1565–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Type | Purpose | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design Ladder [28] | Scale/ questionnaire | To identify the degree of design maturity on a four-level scale for a comparative study among Danish companies. | Pioneer in identifying different levels in the use of design. | Description lacks detail. Aimed at making a comparison between organizations. It does not suggest improvement measures. |

| Design Audit [46] | Questionnaire | To evaluate design performance in internal processes and resulting products in SMEs | It represents the current state and the desired state, to facilitate a plan of action. | A connection with ultimate business goals is missing. It is focused on new product development; other valuable design approaches are missing such as service design, business models or strategies. |

| Design Management Staircase [29] | Matrix | To identify the degree of maturity in five dimensions of design management, in order to carry out a comparative study among nine European SMEs. | Builds on the Design Ladder, adding various dimensions to design maturity. | It does not propose specific actions to increase design capability. Does not connect design capability with business results. |

| Design Thinking Impact [47] | Scale | Conceptual framework to identify the different forms of design impact on an organization from a people behavior perspective, including less obvious but significant forms for business outcomes. | It reveals that design also influences people’s behavior in subtle and unmeasurable, often overlooked ways that significantly impact business results. | It is a conceptual framework, not a practical design evaluation and management tool. |

| Design Capacity Model [45] | Radar chart | To identify and manage the degree of maturity in five dimensions related to design capability. | It proposes a tool not only to measure but also to manage design. | It does not propose specific actions to increase design capability. Does not connect design capability with business results. |

| Design Value Scorecard [30] | Matrix/ process | To identify and manage the degree of maturity in five dimensions related to design capability. | It proposes a process to use the tool for management purposes. | It focuses on “hard metrics”, ignoring other non-measurable aspects of design impact. |

| Design ManagementAudit Framework [31] | Questionnaire | To evaluate an organization’s design processes and their connection to strategy. | It consists of a list of open questions that invite reflection on how to improve design processes. | The results can be confusing and biased because all questions are open-ended and qualitative in nature. Does not connect design capability with business results. |

| Business | Contcen | FoodCollective | Bankop | Propind |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | Contact center and customer care services | Industrial catering services | Bank and financial services | Industrial Property consulting services |

| Size | Medium (~200 people) | Large (+11,000 people) | Large (+2500 people) | Small (~20 people) |

| Interview date | 24 February 2020 | 6 March 2020 | 23 March 2021 | 12 March 2021 |

| Research participants | Director of Projects and Technology 2 Designers Team Coordinator Project Manager | Director of Corporate Innovation Sales Manager | Customer and Service Development Leader 2 Customer and Service Development Technicians Service and UX designer | Managing Director IP Management Lead |

| Experience with design | Design integration is recent. The company redefined and optimized its processes and services based on its own design methods. It offers design as an added value to its services. | Design integration is recent. The company launched a new service for the school sector based on user research and participatory design processes. | Design integration is recent. One team was trained in design and developed a new work methodology. Design was used for the first time in the redesign of mortgage services, though not yet implemented. | Propind outsourced serviced designers for guiding a strategic reflection and the redesign of strategic IP management services. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Legarda, I.; Iriarte, I.; Hoveskog, M.; Justel-Lozano, D. A Model for Measuring and Managing the Impact of Design on the Organization: Insights from Four Companies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212580

Legarda I, Iriarte I, Hoveskog M, Justel-Lozano D. A Model for Measuring and Managing the Impact of Design on the Organization: Insights from Four Companies. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212580

Chicago/Turabian StyleLegarda, Iker, Ion Iriarte, Maya Hoveskog, and Daniel Justel-Lozano. 2021. "A Model for Measuring and Managing the Impact of Design on the Organization: Insights from Four Companies" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212580

APA StyleLegarda, I., Iriarte, I., Hoveskog, M., & Justel-Lozano, D. (2021). A Model for Measuring and Managing the Impact of Design on the Organization: Insights from Four Companies. Sustainability, 13(22), 12580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212580