Predictors of Viewing YouTube Videos on Incheon Chinatown Tourism in South Korea: Engagement and Network Structure Factors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Heritage Tourism and Chinatown in Incheon

2.2. Online Travel Information, Social Media, and One-Person Media

2.3. Determinants of Viewing Tourism Videos on YouTube: Engagement and Network Structure Factors

3. Methodology

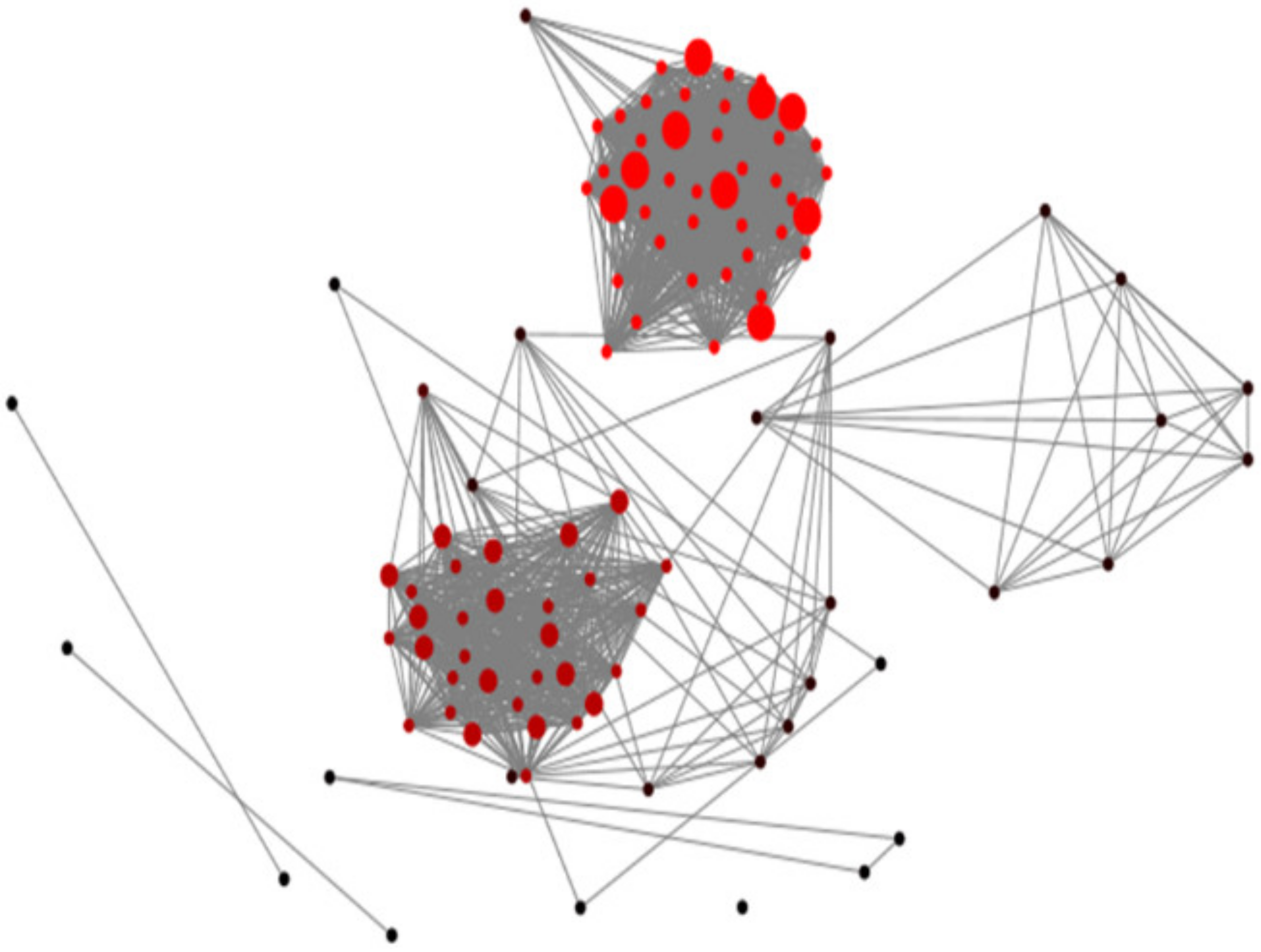

3.1. Data Collection and Preparation

3.2. Analysis Category

4. Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Incheon Metropolitan City. A Study on the Status of Incheon Tourism, 2016; Incheon Metropolitan City: Incheon, Korea, 2017.

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. 2018 International Visitor Survey; Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism: Seoul, Korea, 2019.

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowel, H.; Gribben, H.; Loo, J. Travel Content Takes Off on YouTube. Available online: https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/travel-content-takes-off-on-YouTube/ (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Kang, M.; Schuett, M.A. Determinants of sharing travel experiences in social media. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhong, D. Using social network analysis to explain communication characteristics of travel-related electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherr, S.; Reinemann, C.; Jandura, O. Dynamic success on YouTube: A longitudinal analysis of click counts and contents of political candidate clips during the 2009 German national election. Ger. Polit. 2015, 24, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Cardenas, V.; Zhu, Y.; Enguidanos, S. YouTube videos as a source of palliative care education: A review. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 1568–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velho, R.M.; Mendes, A.M.F.; Azevedo, C.L.N. Communicating science with YouTube videos: How nine factors relate to and affect video views. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 567606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L.H.; Baker, A.; Beer, A.; Rome, M.; Stahmer, A.; Zucker, G. Going viral: Individual-level predictors of viral behaviors in two types of campaigns. J. Inf. Technol. Politics 2021, 18, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D.; Healy, R.; Sills, E. Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. The core of heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silberberg, T. Cultural tourism and business opportunities for museums and heritage sites. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, V.C.; Shircliff, J.E. Heritage spaces in a global context: The case of Singapore Chinatown. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1449–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, T.C.; Liu, J.S.; Lu, L.Y.; Tseng, F.M.; Lee, Y.; Chang, C.T. The main paths of eTourism: Trends of managing tourism through Internet. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevenot, G. Blogging as a social media. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2007, 7, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Gerritsen, R. What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 10, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Measurement and evaluation of satisfaction processes in retail settings. J. Retail. 1981, 57, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hargittai, E.; Walejko, G. The participation divide: Content creation and sharing in the digital age. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2008, 11, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, P.M. Audience Evolution: New Technologies and the Transformation of Media Audiences; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.L. Social media engagement: What motivates user participation and consumption on YouTube? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksiazek, T.B.; Peer, L.; Lessard, K. User engagement with online news: Conceptualizing interactivity and exploring the relationship between online news videos and user comments. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulou, G.; Sheng, C.; Faloutsos, M. A first step towards understanding popularity on YouTube. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Communications (INFOCOM), San Diego, CA, USA, 15–19 March 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, A. COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of popular YouTube videos as an alternative health information platform. Health Inform. J. 2021, 27. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Gu, B.; Whinston, A. Content contribution in social media: The case of YouTube. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; pp. 4476–4485. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarron, E.; Fernandez-Luque, L.; Armayones, M.; Lau, A.Y. Identifying measures used for assessing quality of YouTube videos with patient health information: A review of current literature. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2013, 2, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madathil, K.C.; Rivera-Rodriguez, A.J.; Greenstein, J.S.; Gramopadhye, A.K. Healthcare information on YouTube: A systematic review. Health Inform. J. 2015, 21, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Naaman, M.; Berger, J. A data-driven study of view duration on YouTube. In Proceedings of the Tenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Cologne, Germany, 17–20 May 2016; pp. 651–654. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M.E.; Girvan, M. Finding and evaluating community structure in networks. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 026113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Afrasiabi Rad, A.; Benyoucef, M. Measuring propagation in online social networks: The case of YouTube. J. Inf. Syst. Appl. Res. 2012, 5, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Susarla, A.; Oh, J.H.; Tan, Y. Social networks and the diffusion of user-generated content: Evidence from YouTube. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellis, G.J.; MacInnis, D.J.; Tirunillai, S.; Zhang, Y. What drives virality (sharing) of online digital content? The critical role of information, emotion, and brand prominence. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Rizoiu, M.A.; Wu, S.; Xie, L. Will this video go viral: Explaining and predicting the popularity of YouTube videos. In Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 175–178. [Google Scholar]

- Yoganarasimhan, H. Impact of social network structure on content propagation: A study using YouTube data. Quant. Mark. Econ. 2012, 10, 111–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.W.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, H.W. Networked cultural diffusion and creation on YouTube: An analysis of YouTube memes. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2016, 60, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Kim, S.; Otoo, F.E. Spatial movement patterns among intra-destinations using social network analysis. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Social network analysis. Sociology 1988, 22, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonacich, P. Some unique properties of eigenvector centrality. Soc. Netw. 2007, 29, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liikkanen, L.A.; Salovaara, A. Music on YouTube: User engagement with traditional, user-appropriated and derivative videos. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, R.N.; Real, K. How behaviors are influenced by perceived norms: A test of the theory of normative social behavior. Commun. Res. 2005, 32, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spartz, J.T.; Su, L.Y.F.; Griffin, R.; Brossard, D.; Dunwoody, S. YouTube, social norms and perceived salience of climate change in the American mind. Environ. Commun. 2017, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabash, S.; Baek, J.H.; Cunningham, C.; Hagerstrom, A. To comment or not to comment? How virality, arousal level, and commenting behavior on YouTube videos affect civic behavioral intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thurman, N, Forums for citizen journalists? Adoption of user generated content initiatives by online news media. New Media Soc. 2008, 10, 139–157. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.J.; Lim, Y.S.; Park, H.W. Comparing Twitter and YouTube networks in information diffusion: The case of the “Occupy Wall Street” movement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 95, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.E.M. The role of promotional touristic videos in the creation of visit intent to Barcelona. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2017, 3, 463–490. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, M.A.; Park, H.W. More than entertainment: YouTube and public responses to the science of global warming and climate change. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2015, 54, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.W.; Park, J.Y.; Park, H.W. The networked cultural diffusion of Korean wave. Online Inf. Rev. 2015, 39, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.W.; Park, J.Y.; Park, H.W. Longitudinal dynamics of the cultural diffusion of Kpop on YouTube. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 1859–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danowski, J.A.; Gluesing, J.; Riopelle, K. The revolution in diffusion theory caused by new media. In The Diffusion of Innovations: A Communication Science Perspective; Vishwanath, A., Barnett, G.A., Eds.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, S. A sustainable tourism policy research review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, J.; Shen, H.; Law, R. Research in sustainable tourism: A longitudinal study of articles between 2008 and 2017. Sustainability 2018, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, F.; Nash, N.; Whitmarsh, L. Big data or small data? A methodological review of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Di Felice, M.; Mura, M. Facebook as a destination marketing tool: Evidence from Italian regional Destination Management Organizations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadis, M.D.; Van Zyl, C. Electronic word-of-mouth and online reviews in tourism services: The use of twitter by tourists. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 13, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Before Data Refinement | After Data Refinement | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of nodes | 500 | 104 |

| Number of links | 34,788 | 1463 |

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of views | 1.00 | 40,478.00 | 1835.54 | 5245.696 |

| Number of comments | 0.00 | 181.00 | 11.22 | 31.51 |

| Number of likes | 0.00 | 1353.00 | 44.21 | 162.99 |

| Number of subscribers | 0.00 | 443,171.00 | 21,583.20 | 64,134.99 |

| Running time of content | 25.00 | 4033.00 | 873.21 | 882.51 |

| Degree centrality | 0.00 | 43.00 | 28.14 | 15.37 |

| Betweenness centrality | 0.00 | 3.78 | 0.49 | 1.10 |

| Eigenvector centrality | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Predictors | β | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of comments | 0.21 | 15.54 | 2.26 * |

| Number of likes | 0.57 | 4.05 | 4.65 *** |

| Number of subscribers | 0.12 | 0.01 | 1.43 |

| Running time of content | 0.22 | 0.29 | 3.32 ** |

| Degree centrality | −0.13 | 21.54 | −1.07 |

| Betweenness centrality | 0.02 | 263.10 | 0.27 |

| Eigenvector centrality | 0.07 | 388,335.10 | 0.63 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.75 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoo, W.; Kim, T.; Lee, S. Predictors of Viewing YouTube Videos on Incheon Chinatown Tourism in South Korea: Engagement and Network Structure Factors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12534. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212534

Yoo W, Kim T, Lee S. Predictors of Viewing YouTube Videos on Incheon Chinatown Tourism in South Korea: Engagement and Network Structure Factors. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12534. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212534

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoo, Woohyun, Taemin Kim, and Soobum Lee. 2021. "Predictors of Viewing YouTube Videos on Incheon Chinatown Tourism in South Korea: Engagement and Network Structure Factors" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12534. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212534

APA StyleYoo, W., Kim, T., & Lee, S. (2021). Predictors of Viewing YouTube Videos on Incheon Chinatown Tourism in South Korea: Engagement and Network Structure Factors. Sustainability, 13(22), 12534. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212534