The Standardization Process as a Chance for Conceptual Refinement of a Disaster Risk Management Framework: The ARCH Project

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of Resilience Approaches

2.1. Approaches for Climate Change-Related Resilience of Historic Areas

- (1)

- Assessment—vulnerability and risk assessment.

- (2)

- Reporting and presenting results at the political level.

- (3)

- Planning, implementing, and monitoring adaptation measures.

2.2. Standardization in Research Projects on Climate Change-Related (City) Resilience

3. Methodology

4. Results

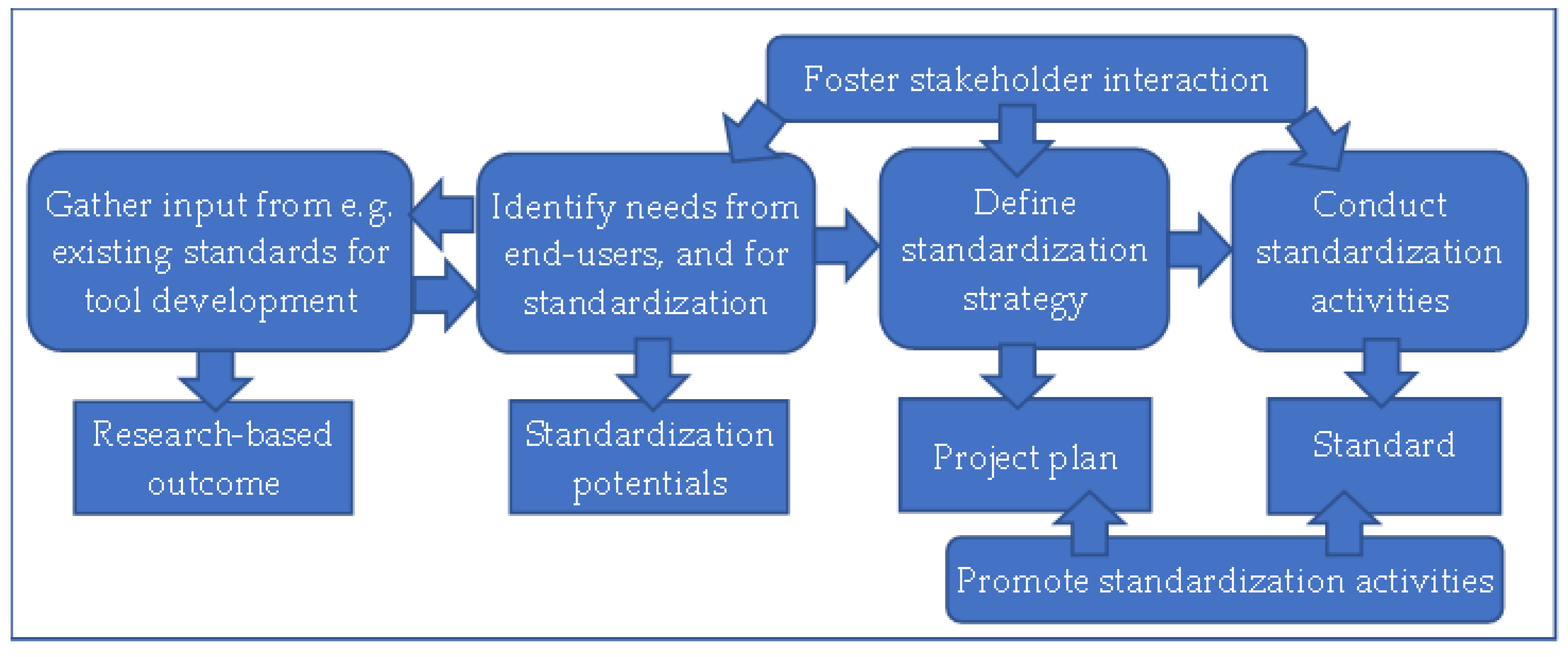

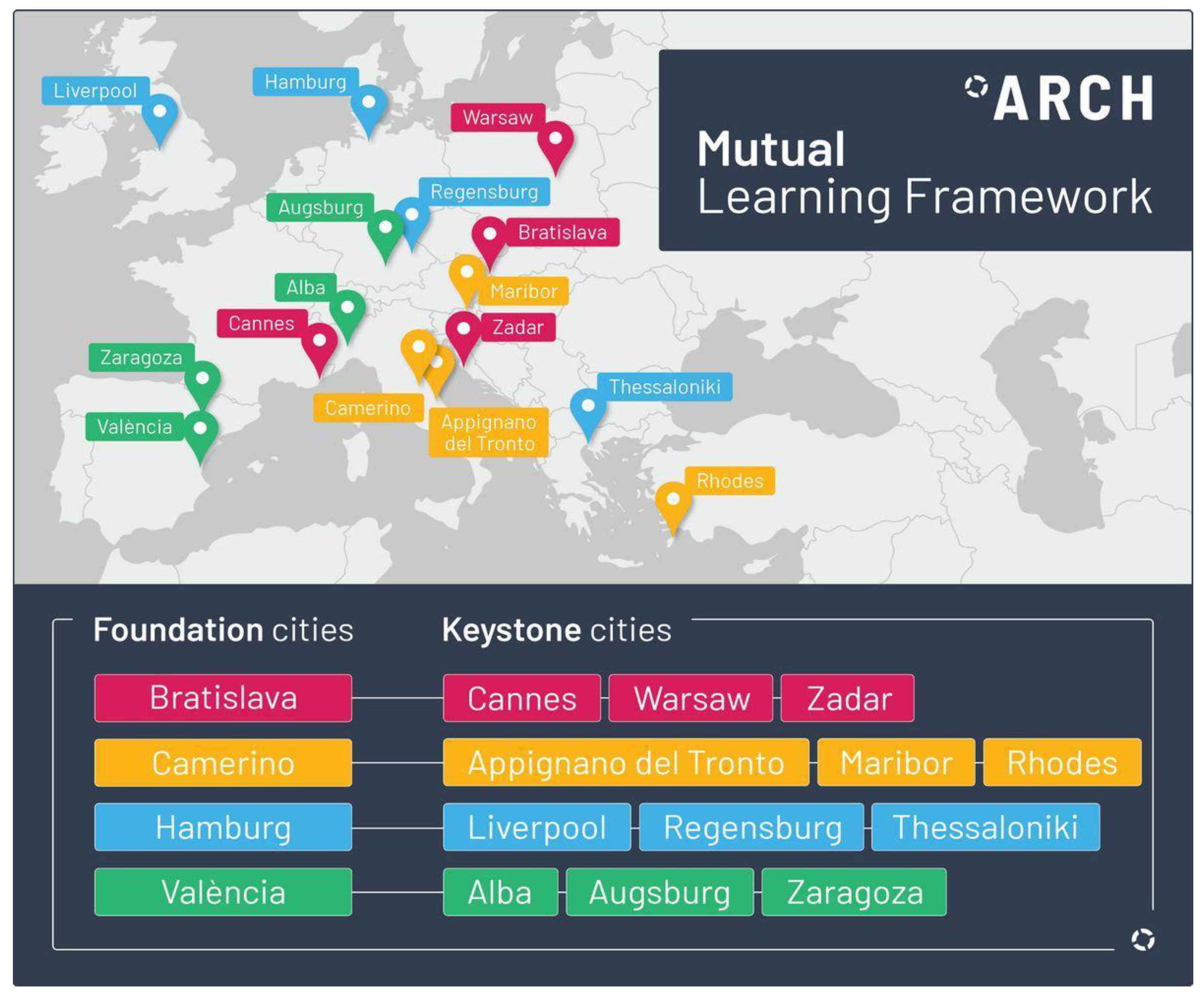

4.1. Standardization and Co-Creation within the ARCH Project

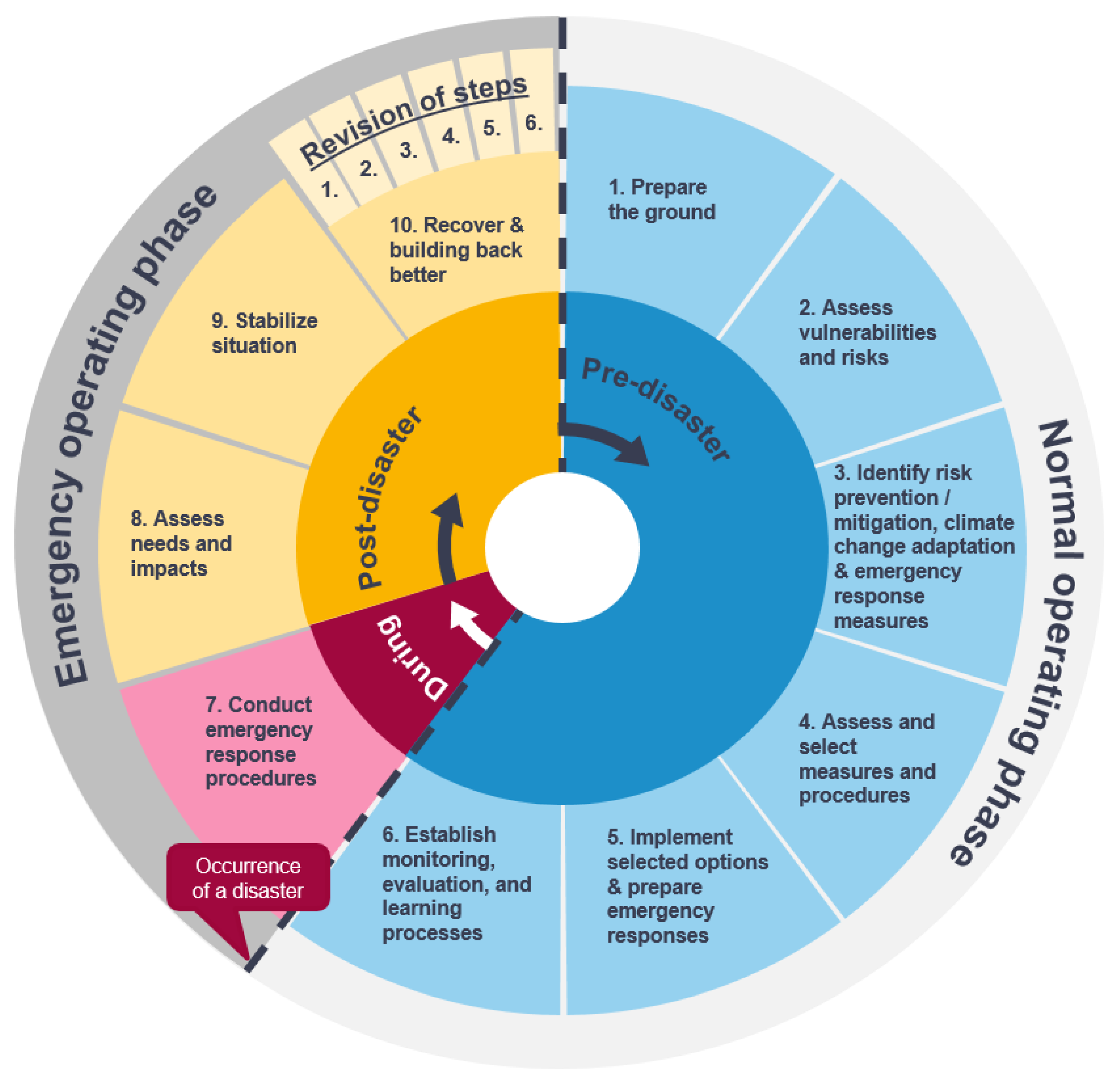

4.2. DRM Framework Development Considering Standards

4.3. Standardization Strategy of ARCH

- Definition of terms and definitions for the resilience of historic areas.

- The resilience building of historic areas in cities and communities, including characterization of historic areas, indicators for resilience assessment, and processes to manage and monitor resilience building.

- The impacts of damages on historic areas caused by climate change-related hazards, including existing heritage metadata of descriptors for risk assessment.

- How to develop, implement, and maintain an alert system for historic areas.

- Involvement of people and organizations in research projects that are not familiar with such projects: e.g., a guideline on how to create a mutually beneficial partnership.

4.4. Developing a Standard on the DRM Framework by Including Co-Creation Activities

5. Discussion of the Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Europe’s Cultural and Natural Heritage in Natura 2000; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2018; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/management/pdf/Nature-and-Culture-leaflet-web.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Nicol, S.; Roys, M.; Ormandy, D.; Ezratty, V. The Cost of Poor Housing in the European Union; University of Warwick: Coventry, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.bre.co.uk/filelibrary/Briefing%20papers/92993_BRE_Poor-Housing_in_-Europe.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- European Commission. Overview of Natural and Man-Made Disaster Risks the European Union May Face; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/echo/sites/default/files/overview_of_natural_and_man-made_disaster_risks_the_european_union_may_face.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- García-Soriano, D.; Quesada-Román, A.; Zamorano-Orozco, J. Geomorphological hazards susceptibility in high-density urban areas: A case study of Mexico City. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2020, 102, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Román, A.; Villalobos-Portilla, E.; Campos-Durán, D. Hydrometeorological disasters in urban areas of Costa Rica, Central America. Environ. Hazards 2021, 20, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2021, 16th ed. 2021. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2021.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- ICOMOS. Resolutions of the General Assembly. In Proceedings of the 19th General Assembly of ICOMOS, New Delhi, India, 11–15 December 2017; Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/General_Assemblies/19th_Delhi_2017/19th_GA_Outcomes/GA2017_Resolutions_EN_20180206finalcirc.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Bigio, A.G.; Ochoa, M.C.; Amirtahmasebi, R. Climate-Resilient, Climate-Friendly World Heritage Cities. In Urban Development Series Knowledge Papers; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/19288 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Markham, A.; Osipova, E.; Lafrenz Samuels, K.; Caldas, A. World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/139944 (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Sesana, E.; Gagnon, A.S.; Bertolin, C.; Hughes, J. Adapting Cultural Heritage to Climate Change Risks: Perspectives of Cultural Heritage Experts in Europe. Geosciences 2018, 8, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- GPDRR—Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction, Heritage and Resilience. Issues and Opportunities for Reducing Disaster Risks; UNESCO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/122923 (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- IPCC. Annex II: Glossary. In Climate Changing: Synthesis Report; Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Mach, K., Planton, S., von Stechow, C., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/resolutions/N1516716.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- United Nations. Paris Agreement on Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2016. Available online: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- United Nations. Website on Sustainable Development Goals. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- The Rockefeller Foundation. Website on 100 Resilient Cities. 2021. Available online: https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/100-resilient-cities/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Resilient Cities Network. Website. 2021. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- UNDRR. Website on Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Cities. 2017. Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/campaign/resilientcities/toolkit/article/disaster-resilience-scorecard-for-cities.html (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Alexander, D. Resilience and disaster risk reduction: An etymological journey. Nat. Hazards Erath Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 2707–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, L.; Faber, M. Impacts of sustainability and resilience research on risk governance, management and education. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2019, 6, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelinger, L.; Turok, I. Towards Sustainable Cities: Extending Resilience with Insights from Vulnerability and Transition Theory. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2108–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holling, C. Engineering Resilience versus Ecological Resilience. In Engineering within Ecological Constraints; Schulze, P., Ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Milde, K.; Lückerath, D.; Ullrich, O. ARCH Disaster Risk Management Framework. EU H2020 ARCH (GA No. 820,999), Deliverable D7.3. 2020. Available online: https://savingculturalheritage.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Deliverables/ARCH_D7.3_Disaster_Risk_Management_Framework_v20201130-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Rockefeller Foundation; ARUP. City Resilience Framework; Ove Arup & Partners International Limited: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/City-Resilience-Framework-2015.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- McCartney, G.; Pinto, J.; Matthew, L. City resilience and recovery from COVID-19: The case of Macao. Cities 2021, 112, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, O.; Bogen, M.; Lückerath, D.; Rome, E. Co-Operating with Municipal Partners on Indicator Identification and Data Acquisition. Simul. Notes Eur. 2019, 29, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Andrée, D.; Llerena, P. A New Role for EU Research and Innovation in the Benefit of Citizens: Towards an Open and Transformative R&I Policy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/57_-_rise_-_a_new_role_for_eu_research_and_innovation_in_the_benefit_of_citizens_-_towards_open_transformativeweber-andree-llerena-new_rolo_research-june15.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1290/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013. Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/3c645e51-6bff-11e3-9afb-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- European Commission. 2018/0224 (COD)—Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council—Establishing Horizon Europe—The Framework Programme for Research and Innovation, Laying Down its Rules for Participation and Dissemination. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2018:0435:FIN (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Poustourli, A. European and International Workshop Agreements: A Brief Example in Security Research Areas. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310242304_European_and_International_Workshop_Agreements_A_Brief_Example_in_Security_Research_Areas (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Lindner, R.; Lückerath, D.; Hernantes, J.; Jaca, C.; Latinos, V.; Peinhardt, K. Bringing Research on City Resilience to Relevant Stakeholders—Combining Co-creation and Standardization in the ARCH project. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Urban Planning, Regional Development and Information Society, Vienna, Austria, 7–10 September 2021; Available online: https://archive.corp.at/cdrom2021/papers2021/CORP2021_104.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- ARCH. Project Website. 2021. Available online: https://savingculturalheritage.eu (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- UNESCO. Managing Disaster Risk for World Heritage. World Heritage Resource Manual. 2010. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/104522 (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- SHELTER. Historic Area Resilience Structure. EU H2020 (GA No. 821282), Deliverable D2.1. 2019. Available online: https://shelter-project.com/download-document/?deliverables/D2.1.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- UNESCO; The World Bank. Culture in City Reconstruction and Recovery. 2018. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/61959_131856wprevisediipublic.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- ICOMOS. Climate Change and Cultural Heritage Working Group. The Future of Our Pasts: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo, V.V.; Latinos, V.; Balenciaga, I.; Roca, R. Good Practices in Building Cultural Heritage Resilience. EU H2020 ARCH (GA No. 820,999). Deliverable D7.2. 2020. Available online: https://savingculturalheritage.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Deliverables/ARCH_D7.2_GoodPractices.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Kontokosta, C.; Malik, A. The Resilience to Emergencies and Disasters Index: Applying big data to benchmark and validate neighborhood resilience capacity. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 36, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernantes, J.; Maraña, P.; Gimenez, R.; Sarriegi, J.; Labaka, L. Towards resilient cities: A maturity model for operationalizing resilience. Cities 2019, 84, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourshed, M.; Bucchiarone, A.; Khandokar, F. SMART: A Process-Oriented Methodology for Resilient Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Smart Cities Conference, Trento, Italy, 12–15 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindner, R.; Jaca, C.; Hernantes, J. A Good Practice for Integrating Stakeholders through Standardization—The Case of the Smart Mature Resilience Project. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsella, S.; Marzoli, M. Smart Cities and Cultural Heritage—Protecting historical urban environments from climate change. In Proceedings of the 14th IEEE International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control, Lamezia, Italy, 16–18 May 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabei, L.; Mochi, G.; Bernardini, G.; Quagliarini, E. Seismic risk of Open Spaces in Historic Built Environments: A matrix-based approach for emergency management and disaster response. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 65, 102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco Cadena, J.D.; Moretti, N.; Salvalai, G.; Quagliarini, E.; Re Cecconi, F.; Poli, T. A New Approach to Assess the Built Environment Risk under the Conjunct Effect of Critical Slow Onset Disasters: A Case Study in Milan, Italy. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraña, P.; Eden, C.; Eriksson, H.; Grimes, C.; Hernantes, J.; Howick, S.; Labaka, L.; Latinos, V.; Lindner, R.; Majchrzak, T.A.; et al. Towards a resilience management guideline—Cities as a starting point for societal resilience. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maresch, S.; Lindner, R. Proposal for CEN Workshop Agreements. EU H2020 SMR (GA No. 653569). Deliverable D6.4. 2017. Available online: http://smr-project.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Documents/Resources/WP_6/2017-11-30_D_6.4_Proposal_for_CEN_Workshop_Agreements.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- De Jong, M.; de Buck, A.; Balder, M.; Bogen, M. RESIN Deliverable 5.1/2.2: Standardization in Urban Climate Adaptation. EU H2020 RESIN (GA No. 653522). Deliverable D5.1/2.2. 2018. Available online: https://resin-cities.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Papers/RESIN-D5.1_Standardization_in_urban_climate_adaptation_NEN_30102018.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- CEN. Website of CEN Boss. 2021. Available online: https://boss.cen.eu/developingdeliverables/CWA/Pages/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Linkov, I.; Palma-Oliveira, J. An Introduction to Resilience for Critical Infrastructures. In Resilience and Risk; Linkov, I., Palma-Oliveira, J., Eds.; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zuccaro, G.; Leone, M.; Martucci, C. Future research and innovation priorities in the field of natural hazards, disaster risk reduction, disaster risk management and climate change adaptation: A shared vision from the ESPREssO project. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J. The three Rs of action research methodology: Reciprocity, reflexivity and reflection-on-reality. Educ. Action Res. 2000, 8, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chein, I.; Cook, S.; Harding, J. The field of action research. Am. Psychol. 1948, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottosson, S. Participation action research: A key to improved knowledge of management. Technovation 2003, 23, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.; Atkinson, M.; Chalmers, H.; Comins, L.; Cooksley, S.; Deans, N.; Fazey, I.; Fenemor, A.; Kesby, M.; Litke, S.; et al. Interrogating participatory catchment organisations: Cases from Canada, New Zealand, Scotland and the Scottish–English Borderlands. Geogr. J. 2013, 179, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cvitanovic, C.; Howden, M.; Colvin, M.; Norströmd, A.; Meadow, A. Maximising the benefits of participatory climate adaptation research by understanding and managing the associated challenges and risks. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 94, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.J. An investigation of stakeholder analysis in urban development projects: Empirical or rationalistic perspectives. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinos, V.; Chapman, E. Guideline on ARCH Co-Creation Approach. EU H2020 ARCH (GA No. 820,999). Deliverable D3.1. 2020. Available online: https://savingculturalheritage.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Deliverables/20201130_ARCH_D3.1.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- DIN. Website on the Principles on Standards Work. 2021. Available online: https://www.din.de/en/about-standards/din-standards/principles-of-standards-work (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Lückerath, D.; Pannaccione Apa, M. ARCH State-of-the-Art Report 3 Building Back Better. EU H2020 ARCH (GA No. 820999), Deliverable D7.1(3). 2019. Available online: https://savingculturalheritage.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Deliverables/ARCH_D7.1_SotA_report_3_building_back_better.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Climate-ADAPT. The Urban Adaptation Support Tool—Getting started. 2021. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/knowledge/tools/urban-ast/step-0-0 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Bours, D.; McGinn, C.; Pringle, P. Monitoring & Evaluation for Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience: A Synthesis of Tools, Frameworks and Approaches; SEA Change Community of Practice and UK Climate Impacts Programme: Oxford, UK, 2014; Available online: http://www.managingforimpact.org/sites/default/files/resource/2014_05_15_sea_change_ukcip_synthesis_report_2nd_edition.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- CEN. Project Plan for CWA 17727. 2021. Available online: https://ftp.cencenelec.eu/CEN/News/WS/2021/ARCH/CEN-WS-ARCH_Project-Plan.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Silva, S.; Guenther, E. Setting the research agenda for measuring sustainability performance—Systematic application of the world café method. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2018, 9, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria/Standardization Potential | Feasibility | Transferability | Filling a Gap | Need for the Document | Input from Externals Needed | Score in Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No | Yes | Neutral | No | Yes | 2.5 |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| 3 | Neutral | No | Neutral | Neutral | Yes | 2.5 |

| 4 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| 5 | No | No | No | Neutral | Yes | 1.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lindner, R.; Lückerath, D.; Milde, K.; Ullrich, O.; Maresch, S.; Peinhardt, K.; Latinos, V.; Hernantes, J.; Jaca, C. The Standardization Process as a Chance for Conceptual Refinement of a Disaster Risk Management Framework: The ARCH Project. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112276

Lindner R, Lückerath D, Milde K, Ullrich O, Maresch S, Peinhardt K, Latinos V, Hernantes J, Jaca C. The Standardization Process as a Chance for Conceptual Refinement of a Disaster Risk Management Framework: The ARCH Project. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):12276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112276

Chicago/Turabian StyleLindner, René, Daniel Lückerath, Katharina Milde, Oliver Ullrich, Saskia Maresch, Katherine Peinhardt, Vasileios Latinos, Josune Hernantes, and Carmen Jaca. 2021. "The Standardization Process as a Chance for Conceptual Refinement of a Disaster Risk Management Framework: The ARCH Project" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 12276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112276

APA StyleLindner, R., Lückerath, D., Milde, K., Ullrich, O., Maresch, S., Peinhardt, K., Latinos, V., Hernantes, J., & Jaca, C. (2021). The Standardization Process as a Chance for Conceptual Refinement of a Disaster Risk Management Framework: The ARCH Project. Sustainability, 13(21), 12276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112276