Abstract

Information and communication technologies (ICT) have allowed the modification of many research methods based on communication. One of them is the Delphi method, especially e-Delphi. The two main areas of application of the Delphi method are traditional forecasting, but recently also the conceptual framework development of a model or theory, especially in complex domains and those where empirical research is lacking. The aim of the study was to assess the substantive accuracy (validation) of the enterprise reputation management maturity model (CR3M) using the modified e-Delphi. The final model will be tested in selected companies in the future (in the next stage of the research). Maturity models have long been regarded as tools for assessing skills in some field. The CR3M model originally included 96 practices (in four areas: communication management, corporate social responsibility, reputational risk and quality), the implementation of which was considered to be a maturity indicator. The basis for the development of the model was the literature on the subject and the existing partial maturity models. Ten experts (five theorists and five practitioners) participated in the study and assessed the appropriateness of including practices in the model and their validity, using a 5-point Likert scale. The questionnaire consisted of three questions. In two rounds of the Delphi study, an expert consensus was reached (in accordance with a priori established indicators) regarding the retention 70 out of 96 practices originally included in the model (26 deleted). The model retained 18 practices in the area of Communication Management, 14 practices in the area of Corporate Social Responsibility, 18 practices in the field of Reputation Risk Management and 20 practices in the field of Quality Management. Modification of the maturity model-reducing the number of practices included in the model increased its applicability. At the same time, 89% of experts found the presented maturity model a useful tool for self-assessment and improvement of reputation management. The modified e-Delphi procedure can be considered as an effective methodology for validating complex conceptual models.

1. Introduction

The subject of the article is related to the application of information and communication technologies (ICT) for the sustainable development of the information society (SIS), although it does so indirectly. The adoption of information and communication technologies in this case does not apply to their application in the enterprise, through appropriate expenditures, developing information culture, improving the management and quality of ICT [1], but using it to validate the theoretical model of corporate reputation management maturity (CR3M), which should ultimately contribute to the development of SIS.

Sustainable development is understood according to Brundtland’s definition as one that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [2]. Sustainable information society (SIS) it is the next stage in the development of the information society, in which information and communication technologies (ICT) are becoming the key enablers of sustainable development [3,4,5]. A sustainable information society is a society that effectively uses knowledge and ICT, constantly learns and improves competences, positively adjusts to emerging trends, and builds the prosperity of present and future generations, while balancing the interests of various stakeholders (citizens, enterprises, NGOs, agencies government, and the natural environment) [1].

It is believed that ICT can contribute to sustainable development in all its dimensions, i.e., ecological, socio-cultural, economic and political [1,2]. Information systems can facilitate sustainable development by creating the kind of economic activity that in the long term harmonizes the natural environment with the well-being of society [3]. In this approach, the use of ICT by enterprises (but also households or public administration) becomes one of the most important tools for building sustainable business practices [2], serving both the improvement of economic results and the wider social interest (e.g., environmental protection) [3].

In this article, ICT is not a direct tool for shaping sustainable business practices, but a tool for validating a model (e-Delphi method) that identifies such practices. Model CR3M can contribute to sustainable development by drawing managers’ attention to those aspects of economic activity that favor ecological, economic and socio-cultural sustainability. It includes practices in the field of communication with stakeholders, corporate social responsibility and quality management.

Improving management based on the model will be conducive to ecological sustainability, as it indicates the basic practices concerning, inter alia, environmental protection, environmental friendliness of the technologies used, designing ecological products, avoiding wastage of resources, etc., without which it is impossible to enjoy a good reputation. The use of the model will also contribute to economic sustainability, as the model indicates specific practices of building a good reputation, thanks to which the company can achieve tangible and intangible benefits that have an impact on economic results (the consequences of a bolder pricing policy, easier access to distribution channels, greater loyalty customers, etc.). The use of the model will also be conducive to socio-cultural sustainability, because a positive reputation is based on the practices of building good relations with stakeholders (fair treatment of employees, providing full information to clients, engaging in local social initiatives, etc.).

The model is therefore intended to improve the management of various aspects of the company’s operations that have an impact on building a positive opinion in the environment, with many of these aspects relating directly to sustainable development. It can be assumed that the targeted practices of building good reputation indicated in the CR3M maturity model will ultimately significantly support the company’s transition towards sustainable development.

The article presents the course of a research procedure using ICT in the Delphi method, aimed at validating the corporate reputation management maturity model (CR3M). The Delphi method has gained in popularity in the last two decades as a methodology for researching research questions. A number of theorists [6,7,8,9,10,11] made a significant contribution to defining the rules increasing the rigor of this type of research and describing the stages of the procedure. This made researchers confident that their results could be used in subsequent research, and managers confident that the information obtained in this way was reliable.

The Delphi method, developed in the 1950s by Rand Corporation, is generally used to gain expert consensus on a specific topic. It is based on the assumption that group judgments are more credible than individual judgments and can be applied in a wide variety of sectors, such as public health, society, transport, education, etc. [12]. The Delphi method was originally used to predict various events and was designed as “a method used to obtain the most reliable consensus of opinion of a group of experts by a series of intensive questionnaires interspersed with controlled feedback” [13] (p. 458). With the widening of its application to (generally) problem solving and the evolution of the classical approach, slightly broader definitions have been proposed. For example, Linstone and Turoff regard Delphi as “a method for structuring a group communication process so that the process is effective in allowing a group of individuals, as a whole, to deal with a complex problem” [7] (p. 3). In turn, Reid believes that Delphi is a method of systematic gathering and aggregation of informed judgment by a group of experts on specific questions and problems [14,15].

Due to the fact that this method puts quite a lot of emphasis on communication (e.g., definitions of Linstone and Turoff or Reid), sometimes—wrongly—it is reduced only to the form of data collection [16], when in fact it is much more; First, as a method of iterative feedback, it develops insight, and thus a deeper understanding of the problem. Second, its essential value is to facilitate consensus, especially in the case of divergent opinions and incomplete knowledge. This ability to develop consent is based primarily on anonymity, giving participants the opportunity to freely express their opinions and eliminating all possible personal conflicts [7,17,18]. The three characteristics of the Delphi method are (i) iteration, which allows participants to rethink and refine their views, (ii) controlled feedback that provides them with information about the group’s views to clarify or change their position, and (iii) statistical analysis, which enables the quantitative presentation of the views of the group [14,18,19,20].

It is believed that the Delphi method is useful especially when dealing with complex problems [21], when empirical evidence is lacking [22], or when knowledge of the problem or phenomenon is incomplete, and is generally used to obtain the most reliable opinion of the group [7,16]. Thus, in addition to traditional forecasts, over time, another important area of its use has come, namely the development of concepts (theoretical frameworks) in which research usually includes the identification and development of a set of concepts and the development of a classification/taxonomy [8]. Maturity models are a type of such theoretical framework.

Maturity models are a kind of compendium of knowledge in a given field and a guide for managers, translating knowledge into specific activities aimed at changing and improving the organization. They are based on the assumption that at various stages of development, enterprises undertake various types of activity, which are related to the level of their skills in a given field. Such models show a certain desirable or logical development path from the initial state to full maturity [23]. The first maturity models appeared at the turn of the 1970s and 1980s, and their simple and practical logic was very quickly appreciated by managers. This initiated the rapid and ongoing development of maturity models in many different areas (by far, most of them were created in the area of process management and project management).

In the maturity model, successive levels describe the degrees of organizational skills, most often from complete immaturity, characterized as ad hoc, lack of organization and chaos (level 1), through repeatability and standardization (level 2), organization and monitoring (level 3), conscious management (level 4), to continuous improvement, as an expression of the highest maturity (level 5) [23]. Each of the levels of maturity has its own characteristics, and there must be a logical connection between the successive steps. This path is reflected in a hierarchical structure in which each level of maturity is precisely described through the characteristics of solutions undertaken in terms of strategies, structures, systems and processes, as well as the methods and tools used. Each of the levels follows logically from the previous one—it is its development and more and more complex continuation. It does not assume the need to achieve the highest level of maturity in a given field in the future, as there is usually no universal pattern of practice in a given field (in this case-reputation management) that fits all organizations. On the other hand, maturity models can play the role of a “road map” that allows managers to diagnose what skills the company currently has and which it lacks, and needs to build them in order to make progress in a specific area.

The article presents the course of the research procedure using the Delphi method to validate the corporate reputation management maturity model (CR3M). The use of ICT allowed for an efficient and convenient form of administration for the participants, as e-mail and an online website dedicated to the study (the so-called landing page) were used to communicate with the panelists, containing the most important information for the participants (e.g., research description, instructions for experts, model description, etc.). The Delphi method allowed, in two rounds, to reach a consensus on whether to leave or reject individual practices in the field of corporate reputation management from the model, and to assess the model’s usefulness. The aim of the article is to show the possibility of using the ICT-based Delphi method to verify complex theoretical concepts such as maturity models. The research methods used include the analysis of the literature on the subject, the modified e-Delphi technique and the evaluation of the results of the research procedure.

The structure of the article is as follows; The next section covers the general theoretical foundations of the Delphi method. The following sections, based on a literature review, discuss in more detail two issues fundamental to the Delphi study: the requirements for recruiting a panel of experts and possible consensus criteria. The fifth part presents the main assumptions of the corporate reputation management maturity model (CR3M) to be validated and the idea of maturity models. Section 4 describes the course of the Delphi study: time frames, characteristics of the panel of experts along with the recruitment criteria, and the content of the research questionnaire. The seventh part presents the results of the study—the number of practices on which an expert consensus has been reached and which should remain in the model, as well as the number of practices rejected. The last, Section 6 is the conclusions of the study, a summary of limitations and practical implications.

2. Literature Review

Many different forms of Delphi research are currently in use and have emerged with increasing use and modification of the approach. These include, for example, “modified Delphi”, “e-Delphi”, “Delphi policy” and “Real-time Delphi” [24]. It is worth emphasizing that not all Delphi techniques strive to achieve consensus; for example, Delphi’s policy aims to support decision-making by sorting out and discussing different views on the “preferred future” [24]. This was reflected in much broader definitions and different interpretations of this method.

Hasson and Keeney point out, however, that this variety of approaches and the lack of a precise definition of the method is a problem from the point of view of methodological rigor [24]. As argued by Rowe and Frewer, the more precise the definitions are, the better the research can be conducted (in terms of greater reliability and validity), the easier it is to interpret the results and the more confidence in the conclusions drawn [24,25]. In addition to the varied definitions of the approach, the Delphi method is burdened with other uncertainties, such as the importance of consensus, the criteria for defining experts, and the sheer multitude of varieties and types of Delphi used. The latter issue is the second major problem of Delphi research, which makes it difficult to establish an appropriate methodological rigor. All the more so as within each Delphi type, the procedures may also differ, for example in the number of rounds, the level of anonymity and feedback provided, as well as the inclusion criteria, sampling approach or method of analysis. No wonder that various adaptations of Delphi have led to considerable criticism of the method itself, and some argue that it even threatens the ability to determine the reliability and validity of the technique [24]. On the other hand, this “capacity” of the method is seen by many as a key benefit that allows flexibility in its application. Reviewing the critical remarks of various authors regarding the Delphi method, Hasson and Keeney conclude that despite justified doubts and methodological flaws, it is difficult to formulate a definitive unequivocal statement as to its reliability and validity—while some argue that this method is not reliable, others say that it is both accurate and reliable [24].

In the conclusion, the authors state that one should strive to achieve the scientific rigor of this method, bearing in mind two issues [24]; First, it should be recognized that Delphi replication at different time-scales misses the goal of most research to explore ideas or to improve decision making by consensus. Additionally, because opinions do not exist in a static vacuum, various confounding variables (such as situation or expert-specific factors) are intrinsically linked to any individual Delphi study. Such factors are rarely controllable and therefore limit the measurement of methodological rigor. Future empirical research should therefore consider the use of parallel measures as well as setting the rigor in each individual Delphi and the inclusion of both qualitative and quantitative measures, as recommended by Day and Bobeva [9] or included in the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) [10].

Secondly, it should be accepted that the Delphi results do not offer an indisputable fact, but rather constitute a kind of a snapshot of experts’ opinions for a specific group, at a given time, especially since the size of the panel does not ensure that the results are representative. This collective opinion of experts can be used to build or verify some concept, practice or theory. Therefore, Delphi’s findings should be compared with other relevant evidence and verified with further research to increase confidence [25]. In order to maximize the quality of the results and solve the problems related to methodological discipline, some researchers propose that the Delphi study be triangulated using other methods used in parallel (e.g., questionnaire surveys and assessment interviews) [9].

The model of research procedure in Delphi conventionally includes three stages: exploration, distillation and use [7]. The first stage, i.e., search or exploration, is a free and unstructured study of the problems, limitations, challenges and problems of the studied domain, sometimes in the form of brainstorming. This phase includes, inter alia, activities such as setting criteria for selecting participants and setting up a panel of experts, designing data collection and analysis tools, etc. Currently, however, there is a so-called modified version of Delphi, that proposes a major overhaul of this first stage; it is about replacing the initial, free set of opinions with a synthesis of key issues identified in the literature or through preliminary interviews with selected field experts, and thus using a structured questionnaire already in the first round [9,11]. The second stage, the so-called distillation, includes (repeated) consultation and subsequent analysis to see if Delphi has reached the critical point for completion of the test. The final step—exploitation—involves the development and dissemination of the final study report.

The two most fundamental issues in the application of the Delphi method are related to the selection of the expert panel and the design of the questionnaire. The first relates to the size of the panel, its main features and response rate, while the second relates to the selection of the Likert scale and the number of rounds [12]. Particularly important when constructing a panel of experts is the awareness of the fact that their experience (practice) and knowledge directly determine the reliability and validity of the results [13,23,26]. In practice, the selected panel selection strategy will probably depend on the nature of the research problem: the narrower the scope and specificity of the field, the greater the depth and specificity of the required specialist knowledge, and therefore the more likely it is that a targeted approach will be appropriate [9].

For this reason, when selecting experts, a target sample is usually used, which allows consciously selecting experts who have knowledge and experience adequate to the specific issue or problem under study. This approach is also particularly useful in cases where there are only a limited number of experts in a given field [27]. Self-assessment scales can be used to assess the expertise of experts, e.g., a five-point scale (in which low numbers indicate a low level of knowledge, and high numbers indicate a high level of knowledge) [7]. Experts are usually identified by reviewing the literature, recommendations of institutions, or recommendations of other experts.

Regarding the size of the expert panel, there are no strict rules in Delphi, but the size of the group is strongly related to the purpose of the study [28], and it is obvious that the group error decreases and the quality of decisions is strengthened as the sample grows [19]. In most Delphi studies, the sample size is tailored to the specific study; it is believed that if, for example, experts who have a similar general knowledge of the problem under investigation are selected, a relatively small sample can be used [29]. Most studies use panels of 15 to 35 people [30], but useful results can also be obtained from small, homogeneous groups of 10–15 experts [31]. The minimum size of the panel is considered to be seven experts [7]. The admissibility of the relatively small size of the panel is very important, including due to the often high dropout rate of experts in consecutive Delphi rounds (with the dropout rate being higher in larger groups of more than 20 members) [16].

The next step in the general Delphi procedure is the so-called distillation, involving multiple gatherings of expert opinions and then analyzing whether Delphi has reached the breaking point by the end of the study. A characteristic feature of this method is the multiple rounds (iteration) of the test. The number of rounds depends on the speed at which consensus is reached and, in a way, on the size of the panel. Theoretically, the Delphi process may be repeated many times until consensus is reached, however, many researchers believe that three iterations are often sufficient to collect the necessary information and reach consensus in most cases [32,33].

The size of the expert panel also matters here. If the group is small, it may turn out that even one round is sufficient [28]. On the other hand, to enable feedback and verification of the answer—which is one of the key distinguishing features of the method—at least two rounds are required [18,28,34]. For large samples of more than 30 experts, usually even three rounds are recommended [7,18,35]. An argument in favor of limiting the number of rounds in the Delphi method is the fact that the participation of panel participants in subsequent iterations often drops quickly—there are cases when the percentage of responses decreases by as much as 40% after each round [9]. In such situations, in order to prevent the number of participants from dropping below the critical level, it is better to sacrifice consensus (at all costs) and finish the study, e.g., after the second round. In the case of the modified version of the Delphi method, when the experts in the first round receive a list of pre-selected items (e.g., from synthesized literature reviews), the number of rounds may be successfully reduced to just two [27].

Many authors emphasize that the number of rounds in the Delphi method depends primarily on reaching a consensus, because in fact it is reaching consensus that is the basis for completing the Delphi rounds, not the other way around. This means that theoretically, the process should continue until the a priori criteria necessary to obtain a consensus are met. On the other hand, however, if the Delphi method is used to develop a concept (theoretical framework) or model, i.e., to verify or validate certain factors/indicators/criteria, this consensus will concern, for example, individual elements of the model. In this sense, consensus will not be a criterion for concluding the study rounds, but merely serves to reject or retain elements of the model/concept. Establishing the number of study rounds a priori also makes sense due to the high dropout rate or the prevention of fatigue in cases where the questionnaires contain a large number of items (some Delphi studies may contain several dozen or more items to consider).

Likert scale is usually used to gather expert opinion in qualitative research that aims to determine the importance of certain items/factors or to screen them out. The most common scales are 5-point or 10-point [12]. On the 5-point Likert scale, two expressions are usually used at both ends of the spectrum: “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree.” The most important criterion for selecting the Likert scale, however, is the purpose of the study. Review studies by Giannarou and Zervas show that 10-point Likert scales are used in the case of testing the level of importance (indicators, factors, etc.), while when the level of understanding between experts is tested, the 5-point scale is the most common [12].

The Delphi technique is an iterative process with repeated rounds of data collection until consensus is reached. Consensus refers to the extent to which each respondent agrees with the idea, element or concept, which is assessed on a numerical or categorical scale [28]. Although the main goal of the Delphi research is to obtain the most reliable consensus of the opinion of a group of experts, the greatest weakness of this method is still the lack of a commonly accepted scientific method for determining the level of consensus [7,12,20,36]. There is no basic statistical theory that determines an appropriate stopping point in the Delphi process. There will always be some amount of oscillation and shifts in group views, but because respondents are sensitive to feedback from the rest of the group, they tend to develop consent [27]. In the literature on the subject, there are many types of criteria used to define and establish consensus in Delphi research, and they are subject to different interpretations of researchers.

These criteria most often measure opinion consensus by frequency distribution, standard deviation, interquartile range, coefficient of variation, or other indicators such as Kendall’s W. Most analyses also include the calculation of the mean and median, as they are used to describe the middle and most common response, representing the central trend [13]. When frequency distribution is used, consensus can generally be reached if a certain percentage of the votes fall within a certain range [36]. According to McKenna, this percentage of responses to a given category should be at least 51%, i.e.,—in other words—only categories selected (indicated) by over 50% of experts (e.g., at least 51% of votes for ratings 4 or 5 in 5-point Likert scale) [37]. In some cases, a certain distance from the mean is also taken into account, e.g., Christie and Barela propose that at least 75% of the participants’ responses “should fall between two points above and below the mean on a 10-point scale” [17].

When it comes to studies using standard deviation to assess the level of consensus, the proposition of Christie and Barela [17] that it should be less than 1.5 is usually accepted. Additionally, a common measure of consensus is the interquartile range, most often used with standard deviation or median [12]. The interquartile range for the 10-point Likert scale should be less than 2.5 [13], and for the 5-point scale it should not exceed 1 [38,39,40].

In quantitative analysis, the Kendall coefficient of compliance is also used to assess the level of expert agreement. The value of W ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 being no consensus and 1 being perfect consensus between lists. In interpreting various values of W, researchers usually use the proposal of Schmidt [6], who assumed that values above 0.7 mean a strong agreement (strong consensus for W > 0.7; moderate consensus for W = 0.5; and weak consensus for W < 0.3). The Kendall value of W therefore determines the next steps: a W-factor of 0.7 or more indicates satisfactory compliance and means that the distillation phase can be completed, however, if W is less than 0.7, the questionnaire must be sent again to the panel members in the next round [8]. Some authors also use the coefficient of variation (i.e., the quotient of the standard deviation and the mean), also reflecting the homogeneity of the observations [41,42]. Usually it is interpreted in such a way that values <25% mean low volatility, values between 25–45% mean average volatility, those between 45% and 100% high volatility, and those above 100%—very strong volatility.

In order to present information on the collective judgments of respondents, Delphi studies also use measures of central tendency, i.e., the mean, median and modal [43]. Generally, the median and modal are used, and in some cases the mean is also acceptable. However, the use of the median based on the Likert scale is definitely preferred in the literature on the subject, as it seems by nature to be the best fit for reflecting convergence of opinions and for reporting results in the Delphi process [11].

Some authors believe that the use of percentage measures is insufficient and suggest that a more reliable alternative is to measure the stability of experts’ responses in subsequent iterations [11]. Measuring the stability of the expert opinion distribution curve in consecutive rounds has an advantage over methods that measure the amount of change in each person’s opinion between rounds (degree of convergence) in that it takes into account deviations from the norm [28]. Thus, the use of measures of stability helps to mitigate the effects of extreme or conflicting positions. Proponents of this approach believe that stability of opinion reflects consensus [43]. This means the need to monitor the continuity of the distribution of respondents’ votes in subsequent rounds. According to Linstone [43], the stability threshold is set by changes of less than 15% between rounds. Such a level means that the responses are essentially unchanged, which is a signal of reaching a consensus and at the same time is a criterion for ending the Delphi rounds [9].

It seems that a good practice in assessing the level of consensus is the combined use of several measures, such as in the proposal [12], which recommends supplementing the simultaneous use of three measures, because each of them individually cannot be considered a good indicator. These measures are: (i) the interquartile range, (ii) standard deviation, and (iii) 51% percent of respondents in the “very important” or “strongly agreeing” categories. The rationale behind this approach is to show that there are cases where the interquartile range and/or standard deviation may fall within the adopted limit, but there is insufficient expert consensus on the significance of the factor (the requirement of at least 51% of the opinion for the value of 8–10 on a 10-point scale, or 4–5 on a 5-point scale), or vice versa—in the first Delphi round, opinions are within the standard deviation below 1.5 and/or 51% of experts respond to the “agree” category and “strongly agree” (i.e., between 4 and 5 on a 5-point scale), but their interquartile range may be above 1. For this reason, to be sure of a consensus, these three measures should be considered simultaneously [11].

The most important assumption of the Delphi method is about developing a consensus, i.e., changing the opinion of experts in subsequent iterations, as a result of receiving information about the opinions of other members of the panel. For this reason, for each subsequent Delphi round, a Controlled Feedback Survey from the group perspective should be designed so that respondents can explain or change their views [12]. Feedback from experts typically includes: (1) statistical summaries that provide measures of central tendencies such as variance, mean and median; (2) comments from individual experts; (3) ranking, percentages and interquarter ranges; and (4) subjective messages as anonymous feedback [28]. On this basis, experts are again asked to revise their assessments for each item, and to explain their views. As proposed by Giannarou and Zervas, the interquartile distance and standard deviation of each variable should be determined, and respondents should change or justify the answer when it is outside this range [12]. The process of pressing the rounds should continue until the criteria established a priori for consensus (or stability) are met.

3. Materials and Methods

A firm’s reputation can be defined as a collective representation of a firm’s past actions and results that describes its ability to deliver valuable results to key stakeholders [44,45]. Reputation is therefore a subjective, collective assessment of a company’s credibility and responsibility. Undoubtedly, the company’s reputation is difficult to manage, as it is based on the perception of the environment—the feelings, beliefs and experiences of stakeholders. It should be treated holistically as an integral part of business management. Reputation management is the responsibility of top management (ultimately the CEO), but mainly in terms of the institutionalization of specific values, structures, methods and procedures, while in fact all employees are responsible for the company’s reputation.

Reputation management combines elements of several management areas, such as stakeholder management, communication, corporate social responsibility, quality or risk, so it requires gathering information from various functional areas, but emphasizes those processes, practices and methods that are specific to gaining and maintaining a good reputation in the environment.

Reputation management, i.e., building a good reputation, and then maintaining it, protecting it, changing or recovering it, are so complex issues that companies often have a big problem with it (often intuitive, ad hoc and chaotic actions are taken). In this area, there is a lack of both strong theoretical foundations that would allow for the integration of existing research, as well as the dissemination of lessons learned and good practices to facilitate management among managers. The conceptual chaos related to the concepts of reputation, image and identity, which is a problem for theoreticians conducting research, also means that the knowledge available in the literature on the subject has little value for managers who consider it too vague and therefore of little use in management practice.

Additionally, in recent decades, there has been a significant change in external conditions, which mean that reputation is now perceived as the most risky area influencing the implementation of the company’s strategy. These include the emergence of a new, powerful stakeholder—online communities that operate according to completely different logic and rules (hyperarchic structures), the increasing globalization of markets and supply chains, which exposes companies to legal and ethical abuse caused by suppliers and cooperatives, constantly growing social expectations towards business (expressed by the idea of corporate social responsibility and sustainable development), strengthening the power of customers and a decrease in their loyalty, or loss of trust in business and growing social skepticism from year to year [46].

In this context, it seems reasonable to develop a tool in the form of a maturity model, which gives an opportunity to improve the effectiveness of reputation management. Such a model provides a certain framework that enables the integration of knowledge about the best practices of reputation management, and also constitutes a kind of roadmap that enables the analysis and assessment of the current situation of the company in this regard. Therefore, it can be a tool that helps to guide the implementation and improvement of the entire system of activities allowing for reputation management.

The reputation management maturity model (CR3M) will allow us to achieve three goals: firstly—to help the company’s management to better understand the complexity and multidimensionality of reputation, secondly—to enable them to self-assess the degree of reputation management maturity in the company, i.e., the current state of advancement of practices in this field, and thirdly—ultimately define recommendations for actions aimed at improving skills in this area (i.e., maintaining a good reputation more effectively and avoiding a bad reputation). Therefore, it can be assumed that showing various factors that determine the effective management of the company’s reputation and making a self-assessment allows the management to determine the level of advancement of the reputation management system and make a more conscious choice of specific practices, setting a certain development path taking into account local conditions and the specificity of activities.

Maturity model development can be described as qualitative research as it is subjective, holistic, interpretive and inductive. The CR3M model uses a stage-gate approach that enables the delivery of more differentiated maturity assessments across complex domains. It involves the application of additional levels of detail that, apart from the overall assessment for the entire organization, allow for separate maturity assessments for a number of separate areas. These additional levels are represented by the so-called Key Maturity Areas (KMA), i.e., certain areas of knowledge, and Capability Areas (CA), i.e., components or domain dimensions that can be called skill areas. Such granularity (detailing) of the model enables the organization to better understand its strengths and weaknesses in a given field, and then to plan specific strategies to improve and better allocate resources.

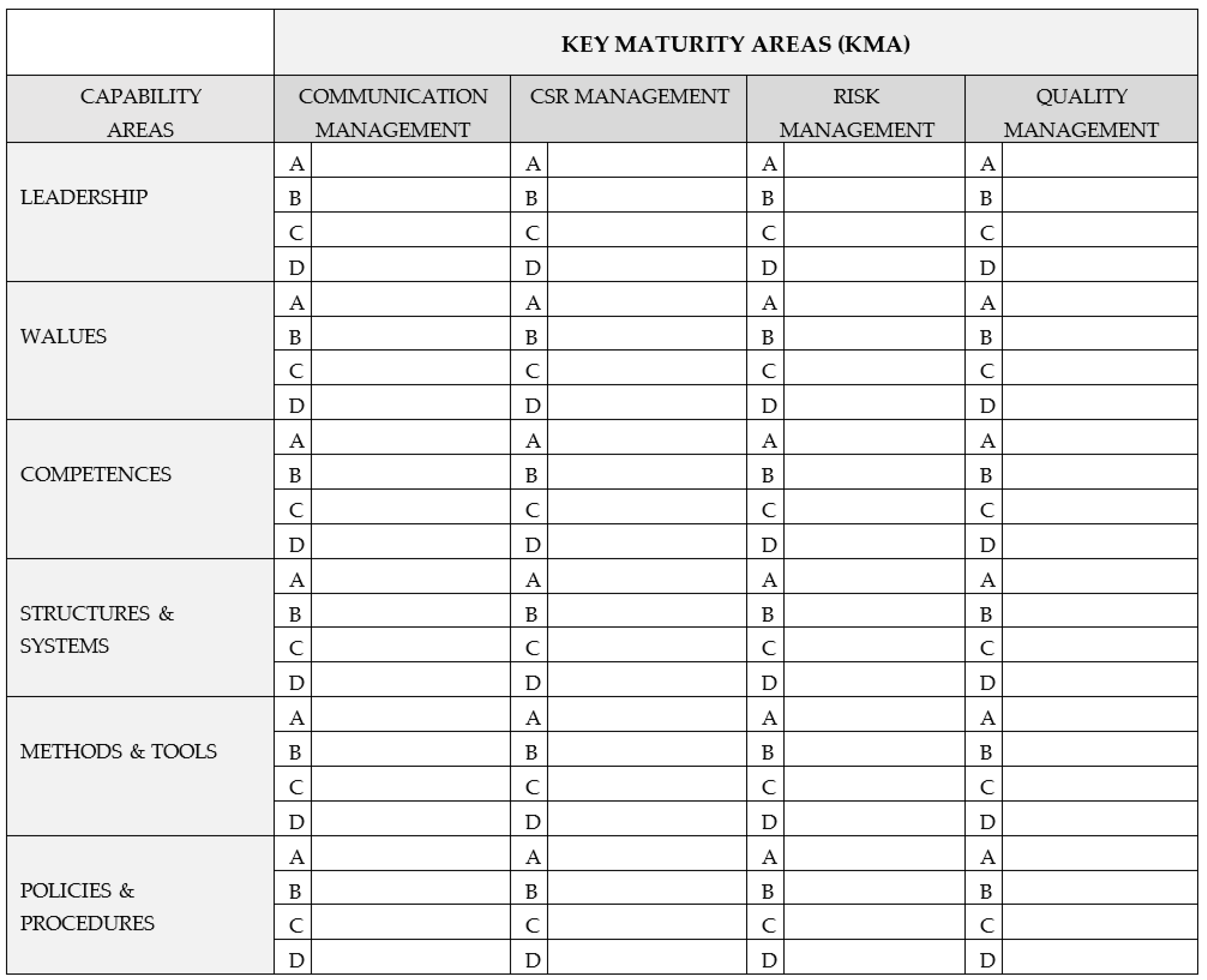

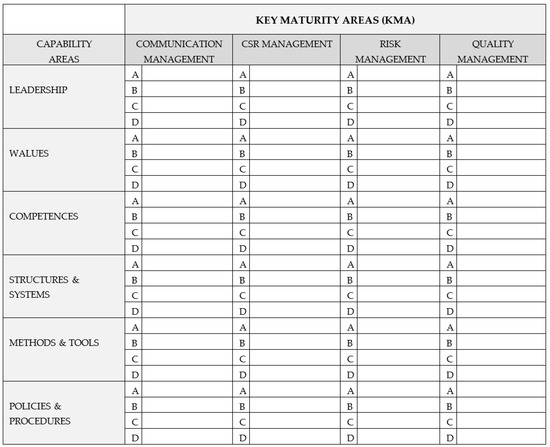

KMA can be treated as key success factors of a given field, the management of which has a significant impact on the organization, so they are the main elements in building the capacity to manage a given area. In the CR3M model, the key maturity areas identified on the basis of the analysis of the literature on the subject are: identity management, communication management, stakeholder relationship management, social responsibility management, issues management, crisis management and quality management. Ultimately, these eight areas were merged into four: communication, social responsibility (CSR), reputational risk and quality (Table 1). Capability areas, on the other hand, include 6 elements: leadership, values, competences, structures and systems, methods and tools, as well as policies and procedures.

Table 1.

The areas of corporate reputation management and their integration in the CR3M model.

In each area of the model (KMA), twenty-four different practices were proposed on the basis of a literature review—four in each CA, i.e., broken down into leadership, values, competences, structures and systems, methods and tools, and policies and procedures (this distinction was not visible to the panelists). These practices are de facto some desirable determinants for the successful management of a company’s reputation. The structure of the model is shown in Figure 1. In total, the model contains 96 practices, which are a structured synthesis of key issues in the field of corporate reputation management that should be verified during the Delphi study. The legitimacy of placing these practices, i.e., the decision whether to leave them, remove them, or modify them (and how) was the subject of the first question of the Delphi study. Each of the practices is described for five levels of maturity, but the experts participating in the study—for greater clarity—received a simplified version of the model, with no levels of maturity shown.

Figure 1.

Structure of the CR3M reputation management maturity model (without showing the 5 maturity levels in each KMA), including 96 practices.

Validation of the model to determine the final content of the model, i.e., the practices that should be included in each area of KMA, is based on expert judgment. The model, verified as a result of the Delphi study, will then be tested in several companies. Ultimately, it is intended to enable the company’s management to self-assess the company’s reputation management practices and to determine the level of maturity in this field, i.e., the degree of advancement of these practices (on a scale from 1 to 5). The degree of maturity for a given KMA is usually adopted at the level of the lowest-rated practice, so it is determined by the weakest link in a given area. The result of such an assessment is a company’s reputation management maturity profile, which graphically illustrates its degree of development in a given field.

4. Results

4.1. Conduct of the Survey

The Delphi study described above focused on developing a group consensus on the components of the enterprise reputation management maturity model. It consisted of a series of two rounds over a nine-month period. The Delphi study aimed to validate the model, whereby validation should be understood as examining the suitability and accuracy of the model as well as obtaining confirmation that it is fit for its intended use. The proposed CR3M conceptual model was presented to a panel of experts through a modified Delphi technique. The first part of the article emphasizes that the Delphi method is particularly beneficial when it deals with complex problems [22] and when there is no empirical evidence [16], and that an important area of its application is the development of concepts/models/theoretical framework [8]. The presented Delphi study meets these criteria because: First—the aim of the research is to develop a conceptual model of corporate reputation management maturity; Second, corporate reputation management is considered a complex domain; And third, there is little empirical evidence about management practices in this area.

In particular, the purpose of the Delphi study was:

- Verification of the current list of reputation management practices as components of the maturity model, i.e., establishing the final architecture of the model—by recommending leaving/rejecting/changing a given practice. The goal was to narrow down the number of practices included in the model (currently 96 practices—24 in 4 areas of KMA);

- Assessment of the importance of individual practices included in the model;

- Assessment (theoretical) of the suitability of the model for self-assessment of the current level of maturity of the company’s reputation management and planning the improvement path.

The description of the model posted on the research website (landing page) contained all the information needed to understand the idea of the presented concept, but without going into details about the individual levels of granulation (without showing that the practices belong to CA, i.e., leadership, values, etc., and without showing maturity levels). This resulted directly from the stated purpose of the study and was intended to prevent unnecessary complication of the entire concept to be assessed. General information about the Delphi study conducted is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of basic information about the Delphi study.

The research procedure consisted of four stages: (1) study planning, (2) expert panel selection, (3) data collection, and (4) data analysis and compilation. The first step was to plan the study, which included, inter alia, designing a research tool, i.e., transforming the maturity model into a questionnaire with questions. The design of a data collection tool is critical both in the exploration and distillation stages, but with regard to Delphi research, there are no clear-cut rules for its design, and the number of issues that can be raised in it (this can range from a few to even several dozen). In the case of this study, the length of the questionnaire reflected the complexity of the problem and the type of data collected. The questionnaire was developed in an Excel file and contained two questions in separate tabs, while in the second round, an additional third question. Each practice was briefly defined in the answer sheet and assigned to a specific area (KMA), the values of the 5-point Likert scale were also described, and a space was provided on the answer sheet to enter your grade and any comment.

In line with the adopted aim of the study, the survey asked experts to verify the current list of 96 reputation management practices as components of the maturity model, i.e., to determine the final architecture of the model by recommending leaving/rejecting/changing a given practice (question 1), assessing the importance of individual practices included in the model (question 2) and the assessment of the model’s suitability for self-assessment of the current degree of maturity of the company’s reputation management (question 3). A 5-point Likert scale was used to assess these issues in all three cases.

The first question of the survey concerned the assessment of the legitimacy of the presence of individual corporate reputation management practices in the presented model. In this question, a 5-point Likert scale was adopted with the following significance of individual assessments: (1)—I strongly disagree with including a given practice in the model-recommendation: DELETE; (2)—I rather disagree with the presence of this practice in the model-recommendation: DELETE; (3)—I partially agree to include this practice in the model-recommendation: MODIFY (in this case, an additional request for clarification and a new definition of the practice); (4)—I rather support including this practice in the model-recommendation: LEAVE (no change); (5)—I strongly support including this practice in the model-recommendation: LEAVE (no change). In the second round, the panelists were asked to take into account the responses of other experts and to consider changing the previous assessment if it was significantly different from the assessments of other experts. Experts also had the opportunity to write a comment or remark on a given practice. Some panelists took advantage of this opportunity, as 2/3 of practices received comments (60 out of 96 practices). All comments were shared (visible) anonymously in the questionnaire until the second round.

In the second question, the panelists were asked to assess the importance of the above-mentioned practices for good (effective) management of the company’s reputation. Again, the 5-point Likert scale was used, where the rating of 1 meant very little importance of the practice, and 5—very high importance. In the second round—as in the 1st question—the panelists were asked to take into account the answers of other experts and to consider changing the previous assessment if it differed significantly from the assessment of other experts.

In the third, additional question (included only in the questionnaire for the second round), experts were asked to assess to what extent the presented maturity model is a tool that allows self-assessment of the current state of reputation management practices in the company and drawing conclusions on the directions of the necessary changes. In this case, a rating of 1 (again a 5-point Likert scale) meant that the model was a completely useless tool for self-assessment and improvement, while a rating of 5 meant that it was definitely useful as a self-assessment and improvement tool.

For all three questions, a priori criteria were established as necessary to obtain a consensus for the assessment of individual practices, which, according to the recommendation of Giannarou and Zervas [12], included three measures: (1) at least 51% of answers to categories 4 or 5; (2) interquartile range < 1; and (3) standard deviation < 1.5.

To facilitate communication and maximize time savings, the survey was carried out using an online website (so-called landing page) and e-mail. At the planning stage of the study, information was prepared and posted on the project website. The landing page was specially designed for this study, providing all panelists with online access to the following information: project description, expert panel, expert guide, model presentation and glossary. The planning stage of the study was completed by the preparation (editing) of invitations for experts, which were then sent by e-mail.

The second stage consisted of activities related to the organization of a panel of experts. The selection of a panel of experts is a very important aspect of the Delphi method, in fact decisive for the success of the study and the quality of its results. The narrow scope of the field covered by the model (a limited number of expert theorists) and the depth and specificity of the required specialist knowledge made the selection of a panel of experts used a deliberate approach. In fact, there is no set of universal guidelines for qualifying experts for a Delphi panel [47]. In this study the panel of experts was selected on the basis of their knowledge or professional experience in corporate reputation management.

When determining the list of potential panelists, care was taken to ensure a balance of views from a theoretical and practical perspective, therefore the recruitment of experts was based on the academic and industrial environment. In the case of theoreticians, the inclusion criteria for the panel were as follows: (1) a researcher with at least a doctoral degree; (2) at least 5 scientific publications on corporate reputation or image management; (3) self-assessment of knowledge and experience in the field of reputation management at a level of at least 3 on a 5-point Likert scale; and (4) consent to participate in the study. Experts—theorists were searched for on the basis of scientific publications in the field of managing the company’s reputation (or image). This group includes people from all the largest Polish academic centers, incl. SGH, UJ, UG, PŚ, University of Economics in Katowice and Wrocław.

In the case of practitioners, the criteria for inclusion in the panel were: (1) recommendation or referral from academics; (2) professional experience of at least 5 years; (3) work in communication, PR, marketing departments or higher management level (board members); and (4) self-assessment of knowledge and experience in the field of reputation management at a level of at least 3 on a 5-point Likert scale. In the process of recruiting practitioners, the recommendation and command procedure was applied, using the personal contacts of theoreticians who agreed to participate in the study. They were asked to indicate people who could become experts due to their position and professional experience.

Invitations to participate in the study were sent to a total of 36 experts, contacted by e-mail (August–September 2020). In the invitation, potential experts were informed about the purpose and assumptions of the study, and were provided with a link to the online landing page, where in the Expert Panel tab, a short metric with a consent form for the use of their personal data for the purposes of administering the study was posted. Nineteen people responded positively to the invitation, agreeing to participate in the study and filling in the form. Ultimately, however, 15 experts took part in the first round of the study (8 people reported in September and October, and after the recruitment of another 7 people in December 2020), and 10 experts in the second round, returning completed questionnaires. The response rate was 79% for the first round and 66% for the second round, therefore it was quite low and resulted in a significant sample reduction for later statistical analysis. The expert panel size of only 10 in the second round is small, but due to the acceptability of such a small sample size for experts who have similar knowledge of the problem at hand, it was considered sufficient [29]. There are known studies where even a 10-person panel of experts [19] is able to provide strong findings. It is generally accepted that the balance or representation of multiple viewpoints and expertise is more important than the size of the panel [48]. The characteristics of the expert panel are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the expert panel.

After completing the form, all panel members received a questionnaire in an Excel spreadsheet via e-mail. The entire study using the Delphi method consisted of two rounds, and therefore required the assessment procedure to be repeated twice. In the first round, it was a standard questionnaire, the same for all experts, while in the second round, the questionnaire was individualized, as it contained assessments of practices from the previous round and statistical data on the evaluations of other members. The first questionnaire (in the first round) contained two questions, while in the second round there was an additional, third question about the usefulness of the entire model.

The experts had 2 weeks to review the content of the worksheet and respond. In the event of no reply at that time, a reminder e-mail was sent to them. In practice, this response time has increased significantly, despite repeated reminders and requests. The low response rate in the first round, amounting for only 42% two months after the start of the survey, necessitated additional recruitment of experts—mainly practitioners. This extended the duration of the first round by another three months (until March 2021), and the entire study until May 2021. According to the author, the main reason for such a delay was—signaled by the panelists—the high degree of difficulty of the survey, its length (the need to evaluate 96 practices twice—in the first and second question of the survey), and therefore the long time needed to complete it.

After the end of the first round, the respondents’ answers were analyzed and recalculated for each expert. Their results—including mean, median, dispersion, inter-quartile ranges, and anonymous comment summaries—were included in individualized sheets prepared for the second round. The information provided to the panelists in these individualized sheets included: (1) the note that the second round concerns the evaluation of the same practices using the same questions and scales as in the first round; (2) previous expert assessments of individual practices; (3) information on whether the assessment of a given expert differed from the assessments of other experts (this information was based on: average of experts’ assessments +/− standard deviation) along with the values of average measures and cohesion measures for the group of experts; (4) possible expert comments on individual practices included in the model; (5) a request to consider a revision of the assessment if the previous expert’s assessment was significantly different from that of other experts; and (6) additional question about the usefulness of the model.

These feedback from the previous questionnaire provided to the panelists formed the basis for the next round of the survey (it lasted from March to May 2021). The answer sheets were sent to the 15 experts who participated in the first round. In the second round, the response rate was lower than in the first round, as only 10 experts sent the questionnaires back. After the end of the second round, the statistics were recalculated.

Administrative services related to the Delphi study as well as data collection and calculation of statistical measures were carried out by IMAS International Ltd. One of the important features of the Delphi research is the principle that the assessments and opinions of experts are completely anonymous, both in filling in the questionnaires and in the subsequent dissemination of the results. To ensure the anonymity of experts, the questionnaires sent to them were properly coded, and the author of the study did not have access to them during the study.

4.2. Study Results—Model Modification

The result of the study is a maturity model on the content of which an expert consensus has been reached, and which can be tested in practice to assess its usefulness as a self-assessment and improvement tool in the area of reputation management. A priori agreed consent criteria for individual practices allowed for the modification of the maturity model; The first question of the survey referred directly to the question of the legitimacy of the presence of individual practices in the maturity model (more precisely, leaving, changing or removing a given practice). The main goal of data analysis in the second round was to establish the degree of consensus among respondents with regard to the appropriateness of leaving/rejecting/changing each of the 96 corporate reputation management practices in four categories.

The experts’ answer to the first question of the questionnaire allowed us to reduce the number of practices in the CR3M model from 96 to 70. All practices for which the aforementioned consent criteria were not met, i.e., 51% of votes for categories 4 and 5, the interquartile range <1 and the standard deviation <1.5, were rejected from the model. As a result, a total of 26 practices that did not meet these three criteria in the second round were removed from the model. There were six practices in the area of Communication Management (CM), 10 practices in Corporate Social Responsibility Management (SM), 6 practices in Reputation Risk Management (RM) and 4 practices in the area of Quality Management (QM). Therefore, the number of practices in the CR3M maturity model decreased from 96 to 70, which significantly increased the applicability of the model and which was also one of the objectives of the study. The list of consensus indicators for question 1 is presented in Appendix A (Table A1). The target CR3M model would therefore consist of 70 practices: 18 CM practices, 14 SM practices, 18 RM practices and 20 QM practices—these are the practices that experts recommended to leave in the model (at least 51% of 4 or 5 grades) and were they fully agree on this decision (interquartile range <1 and standard deviation <1.5). In conclusion, the panelists in the second round estimated that 73% (70 out of 96) of all original practices should remain unchanged in the model. Table A2 in Appendix B shows the 70 practices left in the model based on expert consensus (question 1).

The questionnaire also included a second question about the significance (validity) of particular practices included in the original maturity model of corporate reputation management. The main purpose of data analysis was to establish the degree of consensus among respondents with regard to the importance of each of the 96 corporate reputation management practices.

In this case, the panelists’ assessments can be treated as a guideline for a possible further reduction of the number of practices in the target model, using the same principle as before. If, in this case, all practices for which in the second round did not meet the above-mentioned consent criteria (i.e., 51% of votes for the important and very important categories, the interquartile range <1 and the deviation standard <1.5), a total of 37 praxis should be removed from the model. It would be 9 practices in the area of Communication Management (CM); 11 practices in the area of Corporate Social Responsibility Management (SM); 11 practices in the area of Reputation Risk Management (RM) and 6 practices in the area of Quality Management (QM). Thus, 59 practices would remain in the CR3M maturity model—only those considered by experts to be important or very important for effective corporate reputation management (grades 4 or 5) and on the importance of which there is full agreement among panelists (interquartile range <1 and standard deviation <1.5). The list of statistical measures for the second question in the questionnaire is included in Appendix C (Table A3). The target model would consist of 59 practices: 15 CM practices, 13 SM practices, 13 RM practices and 18 QM practices.

The third, additional question, which was only included in the questionnaire for the second round of the study, concerned the assessment of the presented maturity model as a tool enabling the self-assessment of the current state of reputation management practices in the enterprise and the formulation of conclusions regarding the directions of necessary changes. The rating was again expressed using a 5-point Likert scale, where a score of 1 was a completely useless tool for self-assessment and improvement, and a score of 5 was a definitely useful tool for self-assessment and improvement (Table A4 in Appendix D presents all three questions contained in the survey questionnaire). In this case, 88.9% of experts found the maturity model a useful or definitely useful tool for self-assessment and improvement (grades 4 or 5, median 4), with full agreement, as evidenced by consensus indicators at the interquartile range = 1 and standard deviation = 0.9. The list of statistical measures is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

List of consensus indicators for question 3 (additional) concerning the assessment of the usefulness of the model as a tool for self-assessment and improvement.

Almost 90% of positive assessments of the presented model and the average score of 4.1 (on a 5-point Likert scale) confirm the sense of its development and dissemination among people responsible for managing the company’s reputation or image. It can be said that the panel of experts has accepted the conceptual model that provides the basis for a better understanding and application of corporate reputation management practices.

5. Discussion

The reliability and validity of the research were ensured in line with their understanding in qualitative research. As suggested by some researchers, with regard to qualitative methods, instead of reliability and validity, one should rather talk about credibility, confirmability, reliability, consistency, transferability to other contexts, etc. [49]. The equivalent of validity is credibility, i.e., the degree to which the research results can be regarded as faithfully reflecting some aspect of reality, not distorted by incorrectly collected data, selective and biased observation and correctly interpreted [50,51]. The credibility of the results was achieved thanks to the triangulation of data sources, i.e., the participation of many different experts in fields directly related to corporate reputation management (such as PR, marketing, communication, etc.), representing both theoretical knowledge (academics publishing in the area of reputation management or image management) and practical (managers experienced in reputation management). The credibility of the results was also increased by data triangulation, i.e., supplementing quantitative data (expert assessments) with qualitative data (comments on individual practices), and ensuring the appropriate context of the study, by preparing and providing panelists with a description of the reputation management maturity model (CR3M).

In turn, the equivalent of reliability in qualitative research is dependability, ensured by the quality of the research itself. It is a procedure for controlling the research process, which applies both to its entire course and to its results [49]. Increasing the reliability was achieved by the use of team work, involving the involvement of several researchers in Delphi (the author of the study, the person supervising the study on the IMAS side and the person conducting the statistical analysis of the results), and the quality control of the study, consisting in a detailed description of the assumptions and supervision of the entire study.

Two rounds proved sufficient to reach consensus on the vast majority of the practices included in the original model. The basis for the decision to end the Delphi study after two rounds was to compare the consensus criteria and the stability of the panelists’ responses (coefficient of variation) for both rounds. First, a comparison of the a priori consensus criteria between the two rounds shows that the number of practices that are allowed to remain in the model improves in subsequent rounds, although this is more evident in the case of the second question; For the first question in the questionnaire, the number of practices for which there is agreement in both rounds is practically the same (70 practices), although some practices have changed. On the other hand, for the second question, the number of practices for which there is consent is clearly greater in the second round (respectively: 48 in the first round and 59 in the second).

Secondly, the approval of experts is also indicated by the low value of the CV variation index: in the first round, in more than half of the cases (55% of assessments), this index was at a low level, indicating low variability (<25%), and in the remaining cases it was average level, proving average variability (25–45%), while in the second round, in the case of almost 2/3 of all practices (exactly 72% of assessments), the CV ratio was low, and in the remaining cases at the level of average variability. There was no practice in any of the rounds for which the CV index showed high variability in ratings.

6. Conclusions

The Enterprise Reputation Management Maturity Model (CR3M) submitted to the panel of experts for evaluation originally included 96 practices, which were defined on the basis of an extensive literature review. These practices have been included in four areas important for reputation management, the so-called key maturity areas (24 practices in each), namely Communication Management (CS), Corporate Social Responsibility (CS), Reputation Risk Management (SD) and Quality Management (QM). Ten experts, both theoreticians and practitioners, participated in the study. In the study, a panel of experts expressed an opinion on leaving/removing/changing each of the 96 practices. A consensus was reached on leaving 70 practices in the model: 18 Communication Management practices, 14 Corporate Social Responsibility Management practices, 18 Risk Management practices and 20 Quality Management practices (the list of practices that remained in the model is shown in Table A2 in Appendix B). The a priori accepted criteria of consensus in the case of a recommendation to leave a given practice in the model were: at least 51% of scores 4 or 5, the interquartile range <1 and standard deviation <1.5. In the case of 26 practices, no expert consensus was obtained, and they were rejected from the model. The highest number of rejected practices belongs to the area of CSR (10), while the lowest number of practices in the field of quality management.

It is worth noting that out of the three consensus criteria, standard deviation (<1.5) was met in all 96 cases, while the reason for removal from the model was failure to meet one of the other two criteria, i.e., too small (<51%) number of experts agreeing to leave practice in the model (scores of 4 or 5 on the Likert scale) or too large an interquartile range (>1). Experts were also asked in the survey to list possible other practices in the field of corporate reputation management, but none of the panelists proposed to supplement the model with any new practices. At the same time, 89% of experts considered the theoretical maturity model as a useful or definitely useful tool for self-assessment and improvement. It should be noted that this model will be tested in several enterprises in the future to fully assess its usefulness.

It is worth noting that the validated model, shown to panelists on the survey website, was a simplified version, as it did not reveal the granularity of practices on the so-called Capability areas (leadership, values, competences, structures, systems, policies), nor did it highlight the five levels of maturity described for each practice in the model. It was concluded that too much complication of the model structure presented to the panelists will not increase the understanding of the model, but will only make it difficult for experts to recommend individual practices and the price of their validity. Achieving a consensus of experts on the content of the CR3M model will allow in the future to start the next stage of research, namely to test the model (full, i.e., showing descriptions of individual levels of practice maturity) in selected enterprises.

This will consist in indicating for each practice the level of maturity (from 1 to 5) that corresponds to the actual state of a given practice in the surveyed company. In this way, it will be possible to get an overall picture of the degree of development of reputation management. Such self-assessment will allow managers to identify possible gaps and plan improvement actions in all areas affecting the company’s reputation. Finally, after the testing phase, thanks to the feedback obtained, further corrections will be made and the final assessment of the model’s usability will be verified. It is a condition of the last phase of developing the maturity model, namely its dissemination [24].

The CR3M model modified as a result of consensus is intended to: (1) help the company’s management to better understand the complexity and multidimensionality of reputation, (2) enable a self-assessment of the degree of maturity at which reputation management is located in the company (the current state of practice in this field), and (3) define recommendations for actions aimed at improving skills in this area, enabling a gradual increase in its maturity (maintaining a good reputation more effectively and avoiding a bad reputation).

Conclusions from the use of the e-Delphi method to validate the theoretical model can be divided into two areas. The first is related to the procedure that uses ICT in the research, while the second concerns the advantages of the Delphi method as a comprehensive research tool.

The advantages of an ICT-based study are widely known, they can be reduced to the possibility of shortening the time between consecutive rounds and, as a result, accelerating the procedure [7], easier administration of the study, ensuring a good context of the study in the form of access to information about the course and subject of the study, the possibility of acquiring experts from various, even geographically distant centers and enterprises, and the ease of ensuring the anonymity of experts and their convenience.

A study conducted 20 years ago by Linestone and Turoff showed that the use of computer technology can shorten the process between rounds in the Delphi process [7]. However, in the case of the Delphi survey described above, this was not the case, mainly due to the high degree of difficulty of the survey (the complexity of the model—96 practices to be evaluated), and—consequently—the high drop-out rate among experts. Therefore, it can be concluded that the use of Delphi questionnaire as a research tool should take into account the limitation of the questionnaire’s complexity and comprehensiveness. Although the Delphi method has been used many times to evaluate a large number of conceptual elements (often 50 or more items to be considered), the complexity of the questionnaire definitely decreases the willingness to participate in the study, and then affects the fatigue of panelists and clearly reduces the response rate in subsequent rounds.

However, the use of ICT allowed to confirm other benefits of this variation of the Delphi method. Providing experts with access to a specially designed website (landing page) provided the right context for the study; It allowed everyone to get acquainted with the concept of the proposed maturity model and detailed instructions describing the course of the study, ensured a common understanding of the terms thanks to the glossary, and finally enabled quick obtaining of personal data with confirmation of consent to participate in the study. Communicating with the panelists via e-mail allowed for the inclusion of experts from various universities in the country, which confirms that it is an effective way of collecting opinions from geographically dispersed experts [52]. The use of the Internet and e-mail also made it easier to maintain the anonymity of the respondents—through coding the questionnaires and the intermediation of a research company. Providing them with anonymity of statements (comments) and assessments is an important attribute of Delphi research, helping to avoid the influence of group dynamics, strong personalities or group conformism that may appear during personal interactions between participants [52]. The use of e-mail also turned out to be the most convenient form for busy experts. In summary, ICT technology is an invaluable aid in conducting Delphi research. Problems related to the application of this method, which were an obstacle two or three decades ago, can now be successfully solved using ICT, providing a friendlier environment, easier administration and faster obtaining of results. Online research methods, such as e-Delphi, have become extremely popular, as they are associated with convenience for participants, time and cost savings, and many data management options [53].

The second group of conclusions concerns the advantages of the Delphi method as a comprehensive research tool. It should be emphasized that the Delphi technique is a qualitative tool that is used to obtain expert opinion, especially when knowledge about a problem is limited. First of all, the Delphi method provides a flexible tool for collecting and analyzing data, discovering and filling gaps in certain areas of knowledge, thanks to the involvement of people who are well-versed in a given topic. In the described case, the Delphi method made it possible to collect opinions from experts in the field of which the maturity model relates, i.e., corporate reputation management. The Corporate Reputation Management Maturity Model (CR3M) initially included 96 practices, the implementation of which was considered (based on an analysis of the literature on the subject) as an indicator of the development of this area. As a result of two rounds of Delphi study, experts agreed to keep 70 practices in the model and found the model a useful tool for self-assessment and improvement. The experts’ assessment therefore helped to select the most important practices and decided on the final establishment of the maturity model architecture. The use of the e-Delphi method allowed us to combine the opinions of experts in order to achieve an informed group consensus on the complex problem [] of determining the content of the maturity model.

The Delphi method has known limitations, such as the use of non-randomized samples, subjectivism and bias imposed by the composition of the expert panel, and the lack of commonly accepted recommendations regarding the number of participants, rounds, the way of defining the consensus, or poor definition of reporting criteria [43]. The most serious limitation in the use of this method, confirmed in this study, concerns the design of the research tool itself, which is the survey questionnaire; Its complexity directly determines the possibility of maintaining the interest of experts in the study and the percentage of their resignations in subsequent rounds. In the case of the presented study, a significant limitation was also the small size of the sample: the panel of experts in the second round consisted of only 10 people. Such a small size of the panel resulted, firstly, from the relatively narrow field of knowledge covered by the model, and thus difficulties in attracting more expert-theorists, and secondly, from the high dropout rate in the second round of the study (34% of experts did not join to the second round). Low response rates in subsequent rounds are another important limitation that should be taken into account when deciding on this method.

Overcoming this limitation requires from the participants a great personal commitment [48], which—unless it results from their high internal motivation—should be maintained by skillful motivation by the researcher. The high percentage of experts’ resignation in the described study could have resulted not only from the high difficulty of the questionnaire (evaluation of 96 practices), but also from too low intensity of communication. Sending two automatic reminders two and four weeks after the questionnaire was sent, and additionally—after another two weeks—a personalized e-mail from the author of the study, should be considered insufficient. This is supported by the fact that in addition to studies that show a significant reduction in response rates in subsequent rounds, there are also studies that show an impressive 90% response rate over five rounds Delphi [54]. In this case, apart from the involvement of the participants, an important role was played by the use of frequent and varied communication. Multiple e-mail reminders, and even phone calls and text messages seem to be acceptable and tolerable in the e-Delphi method as a form of maintaining the interest of panelists [55], especially if the time intervals between consecutive rounds are significant (months).

Another limitation was the use of a panel composed only of Polish experts. In the future, this type of research should consider extending the panel of experts to include people from different countries, and thus increase the representativeness of the panel. In addition, the study used a modified version of Delphi, which means that a structured questionnaire was used in the first round, instead of the open round as in the classic Delphi version. This approach is sometimes criticized for imposing a conceptual framework rather than developing it inductively [43]. The structured approach did seem appropriate in this case, however, given the complexity of the CR3M Enterprise Reputation Management Maturity Model. The questionnaire sent to the panelists, developed on the basis of the CR3M model, where 96 practices had to be assessed, turned out to be so complicated and thus time-consuming that it resulted in the resignation of a large number of experts after the first round. Increasing the difficulty of the study—in the form of inductively developing a model from scratch—would further reduce the chances of its completion. This limitation was somewhat controlled by allowing panelists to comment on practices, suggest new practices, or modify existing ones already in the model.