1. Introduction

At the end of the 20th century, developed countries lived a presumptuous prosperity that was in no case shared with the poorest countries of the planet or with the most vulnerable social strata of the first world that Greenspan [

1] metaphorically called “Irrational Exuberance”. Indeed, the real foundations of that era of prosperity were very weak, and they meant a gradual distancing of investors from the Real Economy or, also metaphorically speaking, from the “Sweat Economy”. Faced with non-speculative investment in real and tangible assets, increasingly sophisticated synthetic financial products proliferated, such as Subprime mortgages, which, in the opinion of Shiller [

2], would end up giving rise to the Financial Crisis of 2007–2008, personalized in the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

As a result of the financial crisis, a great social discontent about the functioning of the financial system was forged due to the lack of transparency and inefficient financial regulation [

3], which led certain financial institutions to carry out negligent practices lacking any ethical-moral component. For these reasons, bank users began to show interest in so-called “ethical banking”, a relatively new set of banking practices that provides greater transparency and security in their operations compared with conventional banking. In addition, this combats key problems of today’s society, such as climate change, social inequality, gender discrimination and environmental sustainability, facts that encouraged the interest of public opinion towards this area of finance [

4].

The current place occupied by ethical banking in the financial context [

5] has come to configure in the words of [

6] “a new international Economic Order” in which the authors of the change are a series of credit interlocutors [

7] who believe in the possibility of combining economic growth from a perspective in which moral values prevail over purely economic values. According to the basic scheme of Ethical Banking, the client is the center of the banking business, promoting through its actions a network of users in which the interests of savers and shareholders are matched with social mentalities fully focused on active solidarity [

8].

In this way, the aim is to seek real solutions to the problems arising from the lack of access to the most essential economic goods, attempting to eradicate poverty, social inequalities, alleviate diseases or environmental degradation. The approach is simple and conclusive: All people must be economically interdependent and self-sufficient in order to preserve the planet for current and future generations. Hence, the need to pursue the fulfillment of a series of ethical-moral values that guarantee the improvement of people’s quality of life [

9].

Faced with the economic tensions caused by the Financial Crisis of 2007–2008, banks turned their eyes to the classic approach of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), attempting to strengthen their reputation in order to increase the trust of their clients by avoiding, as far as possible, the incorporation of financial products with speculative risks among the services offered, improving transparency in their operations and recovering their interests lost in the Real Economy by taking measures to evaluate the impact of their investments in the social and environmental sphere [

10].

In other words: the approach provided by Ethical Banking served as a benchmark to assess the extent to which financial institutions are able to contribute to economic prosperity, environmental quality and the common welfare of all members of society [

11] without creating any exclusion mechanisms between them.

In this research work, we analyzed the credit institutions that are part of “The Global Alliance for Banking on Values” (hereinafter, GABV) based on a twofold statistical analysis: Cluster Analysis and Factor Analysis to verify whether, a priori, there are significant differences in statistical terms between the two most representative prototypical institutions of this sector: Ethical Banks and Poverty Alleviation Banks. In short, the aim is to statistically test the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. There exist two different types of Ethical Banking: Ethical Banking per se and Poverty Alleviation Banking.

Although ethical banks correspond to a single common initiative aimed at putting a definitive end to the financial exclusion; there is no single typology of “ethical bank”. On the contrary, the range of ethical institutions is constantly widening and becoming more diverse. As Brau et al. [

12] indicated, different types of microentrepreneurs have given rise to different ways of implementing the principles of ethical banking, regardless of whether the public opinion may consider that all ethical banks carry out the same kind of activities or that their implementation in countries with very different income levels is based on the same material resources.

This research work seeks to reduce this conceptual gap by means of a detailed analysis and classification of the main ethical banks established worldwide. Consequently, the theoretical implications of this research reveal a direct relationship between the type of demand for these financial services according to the minimum level of vital income, identifying Ethical Banks per se with developed countries (high levels of income in relative terms) and Poverty Alleviation Banks with underdeveloped or developing countries (low or meager levels of income).

The remainder part of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2, provides a global contextualization of Ethical Banking describing, among other points, its historical background, its operating principles and its area of development. Next,

Section 3 describes the sample employed as well as the variables that have been taken into consideration, in addition to the methodological basis implemented: Cluster Analysis and Factor Analysis. Subsequently,

Section 4 presents the results obtained comparing them with respect to Ethical Banking and Banking for Poverty Alleviation. Finally,

Section 5 discusses the findings, defining possible lines of research arising from this work, and

Section 6 concludes the manuscript by highlighting the main conclusions that can be drawn.

3. Materials and Methods

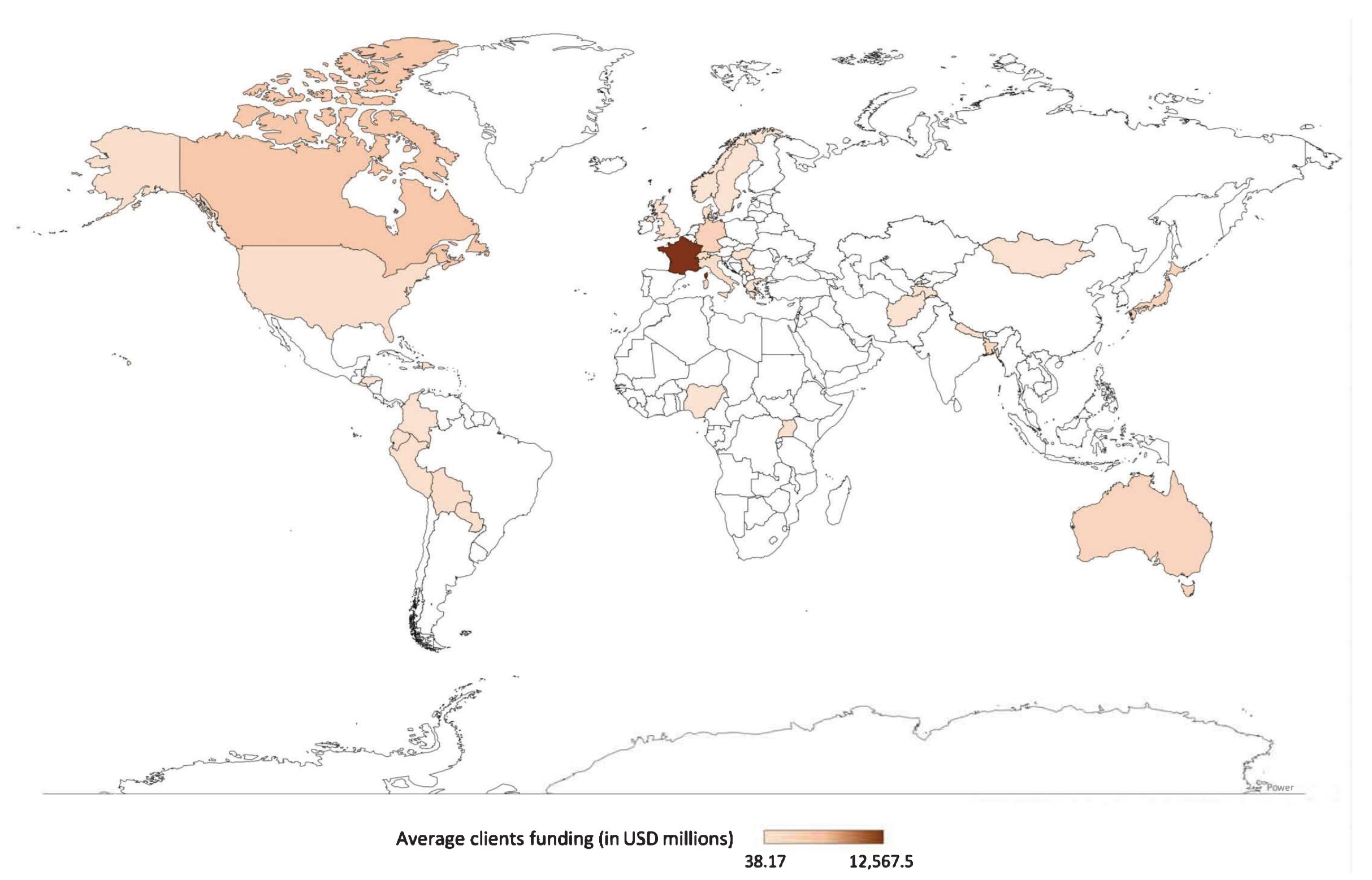

The sample employed is formed by 50 ethical banks that are part of the GABV, distributed across the five continents from 15 global subregions determined according to 2021, as reported in

Table A1 (see

Appendix A), taking, as a reference, the period between 2013 and 2018. First, we considered the variable

(Human Development Index, see UNDP [

52]) since it is based on three key dimensions that are closely linked to the objectives pursued by the Ethical Banking: “Long and Healthy life”, “Knowledge” and “Descent Standard of Living” [

53]. Subsequently, financial data were obtained from GABV [

43] from which the variables

,

and

were selected; afterwards, the following financial ratios were computed and incorporated into the group of variables analyzed:

,

and

.

has been characterized as a proxy variable for human development given that it efficiently synthesizes the degree of progress achieved by each of the 189 countries that comprise it as a function of a coefficient that ranges between 0 and 1, the higher the level of development as it approaches unity and vice versa [

54]. Therefore, a first conclusion regarding the spatial distribution of this index can be gathered: those nations that predominantly present lower values of the variable

are located in Asia, Africa or Latin America, while those with relatively high values are usually circumscribed to nations in Europe, North America and Oceania. This explains why the low values of the variable

are related to banking for poverty alleviation, characterized by a high number of offices, branches and employees due to the lack of solid internet infrastructures or to its vocation to be present in remote areas, elements that make essential the face-to-face contact with the clientele.

On the other hand, the highest values tend to be identified with Ethical Banking, which generally employs on-line tools to interact with its customers, mainly coming from First World countries, which leads to a substantially lower requirement of offices and, in particular, a lower total number of employees than in the previous case, as can be observed in the bar chart displayed in

Figure 2: From the 10 financial entities with the lowest number of employees, 9 correspond to ethical banks per se based in developed countries (see, e.g., Denmark, Greece, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom and the USA). Conversely, 7 of the top 10 banks with the highest number of employees are Poverty Alleviation Banks located in underdeveloped or developing countries (see, e.g., Bangladesh, Bolivia, Colombia, Nigeria, Paraguay, Peru and Uganda).

Table 4 shows the major descriptive statistics of the variables analyzed, distinguishing the total of the sample and the nominal affiliation of the financial entities to both types of Ethical Banking analyzed, presenting several of the stylized facts that characterize both types of institutions. In relation to the Banking for Poverty Alleviation, in comparative terms, we again verified what was previously indicated about the presence of a larger contingent of workers and a predominant adherence to low values of the variable

. Likewise, we confirmed that the total assets are clearly smaller than in Ethical Banking per se, being mainly financed by external contributions while presenting a much higher volume of loans granted. On the other hand, they usually receive a larger quota of deposits and obtain a smaller Net Profit.

Another aspect to consider is the higher degree of variability in all variables in the case of Poverty Alleviation Banking, as measured by the standard deviation and the Interquartile Range. Several reasons may explain such phenomenology. For example, this type of financial entities has a much more atomized clientele than Ethical Banks per se and includes institutions that are, in essence, very similar but relatively heterogeneous and correspond to very different socioeconomic profiles, an aspect that does not usually arise in developed countries whose living standards are becoming increasingly similar in relative terms [

55].

Table 4.

Main descriptive statistics.

Table 4.

Main descriptive statistics.

| A. Total Population |

|---|

| Variable | N | Mean | St. Dev. | Coef. Var. | Minimum | Q1 | Q3 | Maximum | I.Q.R. |

| 275 | 0.82 | 0.13 | 15.95 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.20 |

| 275 | 2055 | 3957 | 192.56 | 57 | 265 | 1773 | 23,674 | 1508 |

| 275 | 0.76 | 0.15 | 19.65 | 0.15 | 0.68 | 0.87 | 0.96 | 0.19 |

| 275 | 0.98 | 0.50 | 50.81 | 0.38 | 0.74 | 10,493 | 60,000 | 0.30 |

| 275 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 100.54 | 346.00 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0.19 |

| 275 | 12.90 | 17.60 | 136.41 | −28.30 | 1.60 | 17.30 | 92.80 | 15.70 |

| 273 | 1032.40 | 1480.90 | 143.43 | 15.00 | 109 | 1425 | 7700 | 1316 |

| B. Ethical Banks |

| Variable | N | Mean | St. Dev. | Coef. Var. | Minimum | Q1 | Q3 | Maximum | I.Q.R. |

| 152 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 1.74 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.02 |

| 152 | 2992 | 5068 | 169.40 | 85.00 | 282 | 3319 | 23,674 | 3037 |

| 152 | 0.84 | 0.07 | 8.60 | 0.59 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.05 |

| 152 | 0.84 | 0.19 | 22.30 | 0.38 | 0.72 | 0.98 | 14,122 | 0.26 |

| 152 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 106.97 | 346.00 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.06 |

| 152 | 11.98 | 19.42 | 162.17 | −28.30 | 0.93 | 13.20 | 92.80 | 12.28 |

| 152 | 376.60 | 622.60 | 165.33 | 15.00 | 63.30 | 356.80 | 2853 | 293.50 |

| C. Poverty Alleviation Banks |

| Variable | N | Mean | St. Dev. | Coef. Var. | Minimum | Q1 | Q3 | Maximum | I.Q.R. |

| 123 | 0.70 | 0.10 | 14.22 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.89 | 0.11 |

| 123 | 897.70 | 968.20 | 107.86 | 57 | 189 | 1246 | 4885 | 1057 |

| 123 | 0.66 | 0.16 | 23.60 | 0.15 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 0.90 | 0.19 |

| 123 | 11.524 | 0.68 | 58.64 | 0.48 | 0.77 | 12,075 | 60,000 | 0.43 |

| 123 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 68.67 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.77 | 0.17 |

| 123 | 14.05 | 15.05 | 107.13 | −1.60 | 2.70 | 19.00 | 66.80 | 16.30 |

| 121 | 1856 | 1804 | 97.17 | 73.00 | 424 | 2760 | 7700 | 2336 |

Although, nominally, there are two types of entities attached to the area of Ethical Banking, their respective missions, motivations, and objectives are very similar, so that the line between Ethical Banking and Banking for Poverty Alleviation is often quite blurred. For this reason, and, taking into account the structural characteristics of each of them according to the variables mentioned above, two types of statistical analysis were conducted, complementary to each other, to differentiate them: Cluster Analysis and Factor Analysis.

The first analysis is especially indicated for the classification of variables according to the degree of association/similarity existing between the items of the same cluster [

57], ensuring that each one of them is internally as homogeneous as possible and externally as heterogeneous as possible. On the other hand, Factor Analysis is a method that seeks to eliminate the redundant information arising from the interrelationships of an initial group of observed variables to a smaller number of latent or unobserved variables generically called “factors” [

58].

5. Discussion

In the light of the findings obtained, this research presents common aspects with previous works. For example, we found that microfinance came to solve the differentiating “gap” that deprived the most disadvantaged members of the globalized society of the right to access financial services [

12]. The fact of delimiting two large clusters (Ethical Banks vs. Poverty Alleviation Banks) verified the study of Bogan [

48] given that the heterogeneity of the capital structure present in these types of entities is simply the result of the different objectives pursued by each one of them, which, roughly speaking, would correspond to two types of philanthropy-driven credit institutions.

These, in turn, are the consequence of two basic approaches that are as distinct as complementary: While Ethical Banks suppose primarily an ethical-moral perspective that aims to reformulate the conventional banking of first-world countries, the Poverty Alleviation Banks represents a step further, providing loans on-site in underdeveloped or developing countries, in which the principles of CSR in financial matters are materialized [

69].

The application of the basic philosophy of these principles has been of great importance in some regions of the planet, such as Asia, having a positive impact on relieving four crucial problems pointed out by Yoshino and Taghizadeh-Hesary [

70] in the performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): difficulties in accessing finance, a lack of information infrastructure, a low level of business R&D and insufficient use of Information Technology. Thus, it is necessary to take into account models aimed at calculating the Optimal credit guarantee ratio for SMEs (see, e.g., Yoshino and Taghizadeh-Hesary [

71]) in which government policies should be directed to the financial support of both banks in general and ethical banking in particular, setting, as an objective, the reduction of the guarantee ratio in assumable economic conditions for the borrowers.

The financial context outlined in this research will soon have to be joined by national banks at the global level to enhance the inherent stability of “ethical banking” and discourage the speculative practices that were at the center of most of the financial crises that occurred during the 20th century. Note that “Alternative Banking” is an element that invigorates the labor factor and whose main task is to ensure the necessary conditions for financial inclusion to expand throughout the world [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76] while facilitating banking operations in various areas that were once alien to conventional banking, such as green finance and investment [

77].

In other words, such is the importance that Ethical Banks have taken on that, according to Atkinson [

78], it forms part of the basis for the Millennium Development Goals, one of the main aspirations of the future generations for cohesion in a just, clean and self-sustainable society.

Novel lines of investigation can be derived from this work. For instance, analyzing the possible ambivalent character of globalization in this sector, given that it has entailed the occurrence of positive elements, such as its worldwide dissemination, at the same time as it has meant an increase in the depletion of the natural resources of the poorest countries. In this sense, it would also be feasible to study the extent to which the average customer profile has changed over time or to infer whether, on the contrary, globalization has resulted in the virtual absence of significant socio-economic differences between the citizens of underdeveloped and developing countries (mainly in Latin America, Africa and Asia).

Finally, the incidence of COVID-19 in these areas would also merit a separate review, given that it has signified a very significant lapse in the growth of these nations [

79], emphasizing how the philanthropic tasks of Ethical Banks can be a powerful instrument to contain the impacts of the pandemic in the most disadvantaged areas of the planet.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to analyze the banks associated with the GABV in order to identify key aspects of their functioning and fundamental characteristics that allow a clear differentiation to be made between “pure ethical banking” and “poverty alleviation banking”. Initially, the two types of banking can be differentiated by looking at their respective missions. The GABV banks have come together to attempt to counteract the social, ecological and sustainability challenges that exist in society. However, each individually defines its own contribution to addressing social needs in light of the different socio-economic situations they face in their country or region [

41].

These research results provide theoretical support for the dual Ethical Banks vs. Poverty Alleviation Banks differentiation, assuming that the existence of minimum levels of living income in developed countries implies that the demand for microcredit is, comparatively speaking, not excessively high in these economies, which is why this subtype of financial industry is precisely more relevant in underdeveloped or developing countries.

Poverty alleviation banking, or “microfinance”, can be defined as a movement that envisions a world in which low-income households have permanent access to a range of affordable, high-quality financial services offered by a variety of retail providers to finance income-generating activities, build assets and stabilize consumption and protect against risks [

80]. Ultimately, they are intended to foster economic development for low-income populations and enhance community development in marginalized areas.

Ethical banking aims to invest in and finance economic activities that have benefits for society and generate a positive environmental impact. In other words, the core of these banking activities has a triple bottom line approach: people, planet and profit [

41]. Both agree on the absence of a profit-maximizing drive, incorporating full transparency in their funding arrangements, which adds to the bank’s attractiveness to savers and depositors, since customers can know what their money is being used for.

We also found that all the banks belonging to the group defined as poverty alleviation banks were established in countries with a lower Human Development Index, essentially countries located in the continents of Asia, Africa and South America. On the other hand, the “pure” ethical banks tended to be located in countries in Europe, North America and Oceania [

41]. From the study conducted, it could be demonstrated that the ratio of loans granted in relation to the volume of deposits was higher in South American, Asian and African countries in relation to Western banks, due to the fact that poverty alleviation banks aim at granting micro-credit to people with lack of resources to promote economic development in marginal areas.

This may be closely related to the fact that ethical banks are heavily funded by customer deposits, which stems from their mission as savings and loan banks that need to raise deposits to give to socially or environmentally conscious businesses or projects. In other words, in order to be able to lend to the companies and projects they want to support, these banks need to collect savings from the market of depositors.

In contrast, poverty alleviation banks rely heavily on other borrowed funds to finance their activities, i.e., they are more dependent on the interbank market, international institutions and microfinance investment funds. However, donors will only provide funds to those banks that are strong, well-managed, with reliable information systems, financial controls adapted to international standards and independent, that show sound financial performance, charging interest rates consistent with the market and that aim to reduce their dependence on the interbank system and increase their long-term operational and financial self-sufficiency [

81].

Therefore, it can be said stated that poverty alleviation banks are overwhelmingly dependent on donor funds and subsidies, which means that they are not financially sustainable, thus, posing a problem to extend the financial services they offer. It is only financially sound organizations that have the capacity to compete, obtain commercial loans, receive deposits and, thus, grow in scale and influence [

82,

83,

84].

One of the features present in the microfinance institution loan contract is the requirement that repayments must begin almost immediately after disbursement and proceed regularly thereafter. Thus, the terms for a one-year loan are determined by adding the total principal and interest due, dividing by 50 and, beginning weekly, collections a couple of weeks after disbursement [

85].

The fact that poverty alleviation banking shows a small higher figure than ethical banking in terms of the average net income can be linked to the above, i.e., poverty alleviation banking with lending attempts to break down each loan into small amounts given in the form of credit to its clients [

86]. This approach involves reducing barriers for (potential) clients to enter into a formal banking relationship by offering simple and transparent products and, in particular, to underserved target groups. In this way, it is diversifying the risk associated with the probability of default, as it provides small loans of small amounts to a large number of clients to be repaid over periods ranging from several weeks to a maximum of one year and at higher interest rates.

The lack of access to credit has led to the emergence of intermediaries, such as microfinance institutions in rural communities in many developing countries, mainly located in marginal areas where the poorest people in these countries live, with precarious resources, including the impossibility of accessing the internet. In fact, 80% of the majority of the poorest population in developing countries live in rural areas. The modalities for granting and repaying loans are fast and flexible.

Therefore, poverty alleviation banking is characterized by close proximity to the clientele, which implies having a larger number of workers who can attend to the needs of the clients without any difficulty [

87]. In general, the application of mobile banking services has not had a great impact in the field of microfinance [

88]. Another notable fact is that poverty alleviation loans are small in size, and thus the costs associated with the operation are high [

82]. However, this banking has new contractual structures and organizational forms that reduce the risk and costs of providing small unsecured loans [

89].

Reducing these costs implies that branches are located close to clients, requiring a large number of small branches for better control [

64], as they aim to serve people living in marginal areas rather than in capital cities, where most banking services are centralized [

41]. Similarly, microfinance faces challenges related to the possibilities of defaulting on loans given to clients. To this end, they have tried to use the capital of the group loans they provide as collateral, attempting to prevail the turnover of money for the benefit of other individual members of the group [

80].

On the other hand, pure ethical banking opts for the development of mobile banking services application on smartphones, which allows customers to easily access their account information. The secure transaction web portals and e-billing allow customers to monitor the process of personalizing their banking services in real time and gradually reduce the need for paper [

90]. This method of intermediating with customers means that a large number of workers are unnecessary, as it is not necessary to have a large number of physical branches. Internet access favors and speeds up the intermediation process between the client and the bank, as well as saving costs. All in all, Western ethical banks have a fairly centralized structure, with very few branches or offices and relatively few staff and relying heavily on internet banking for deposits and payment services [

41].

In short, poverty alleviation banking has a greater number of branches and workers, given the great proximity required to provide its services to the target public, entailing a greater volume of costs. On the other hand, ethical banking, by marketing its services mainly through mobile banking, dispenses with a large number of branches and workers, streamlining its service and being able to save costs associated with its activity.

The differences between ethical banks and microfinance banks in terms of the number of branches, workers and offices are so great that it can be assumed that these types of banks have a completely different organizational structure. In addition, ethical banking has been able to achieve greater diversification of its products by offering its clients the opportunity to invest their savings in sustainable investment funds, i.e., funds that select their assets on the basis of ethical, social and ecological criteria. In contrast, poverty alleviation banking has not extended its activities to this extent.

However, some ethical banks are suffering from their success and growth and may struggle to convert the growing number of deposits into loans. Microfinance banks, on the other hand, are better able to convert deposits into loans. In reality, their problem is that their deposits are insufficient to meet the growing demand for loans, which leads to a heavy dependence on the interbank market for their operation. The success of banks in alleviating poverty may lie in the effective and efficient management of their loan portfolio. The risk of the same may prove to be a problem that challenges the performance and leads to the failure of many microfinance-focused banks [

80].

All banks belonging to the GABV are relatively small but have experienced exponential growth in recent years, especially pure ethical banks, due to a surge in popularity following the financial crisis that began in 2008. Favored by an atmosphere of distrust toward conventional banking, these banks were able to attract a large number of customers with demands for services characterized by transparency, based on ethical values and the real economy and avoiding the speculation embedded in banking products.

The limitations of this research are mainly due to the fact that we included institutions of the largest relative size in financial terms, which, in turn, are the best known globally because of their belonging to the GAV, without taking into consideration smaller financial institutions or even NGOs that provide broadly similar services to the most underprivileged sectors of the community. In the same way, since this study deals exclusively with a differentiating analysis between types of ethical banks, the positive repercussions of these entities for society as a whole in terms of the environment, sustainability, culture or as mechanisms of social co-integration were not thoroughly explored.

In the future, multiple lines of research could be derived from this work. For example, the use of traditional banking determinants, such as profits earned on loans granted, could be included as the main keys to their analysis since, in theory, this is a benchmark measure that encompasses the differential profit margin of one bank over another.