Place-Related Concepts and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Tourism Research: A Conceptual Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To close gaps in the literature on the theory of place research by reviewing the definition of place attachment and related concepts and proposing an extended theoretical framework for the accurate investigation of people–place relationships.

- To review and evaluate current scales and measurement models of constructs included and the structural model of the proposed framework, thereby making recommendations relevant for subsequent empirical research.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Place Attachment

2.2. Place Meaning

2.3. Activity Participation

2.4. Place Satisfaction

2.5. Pro-Environmental Behavior

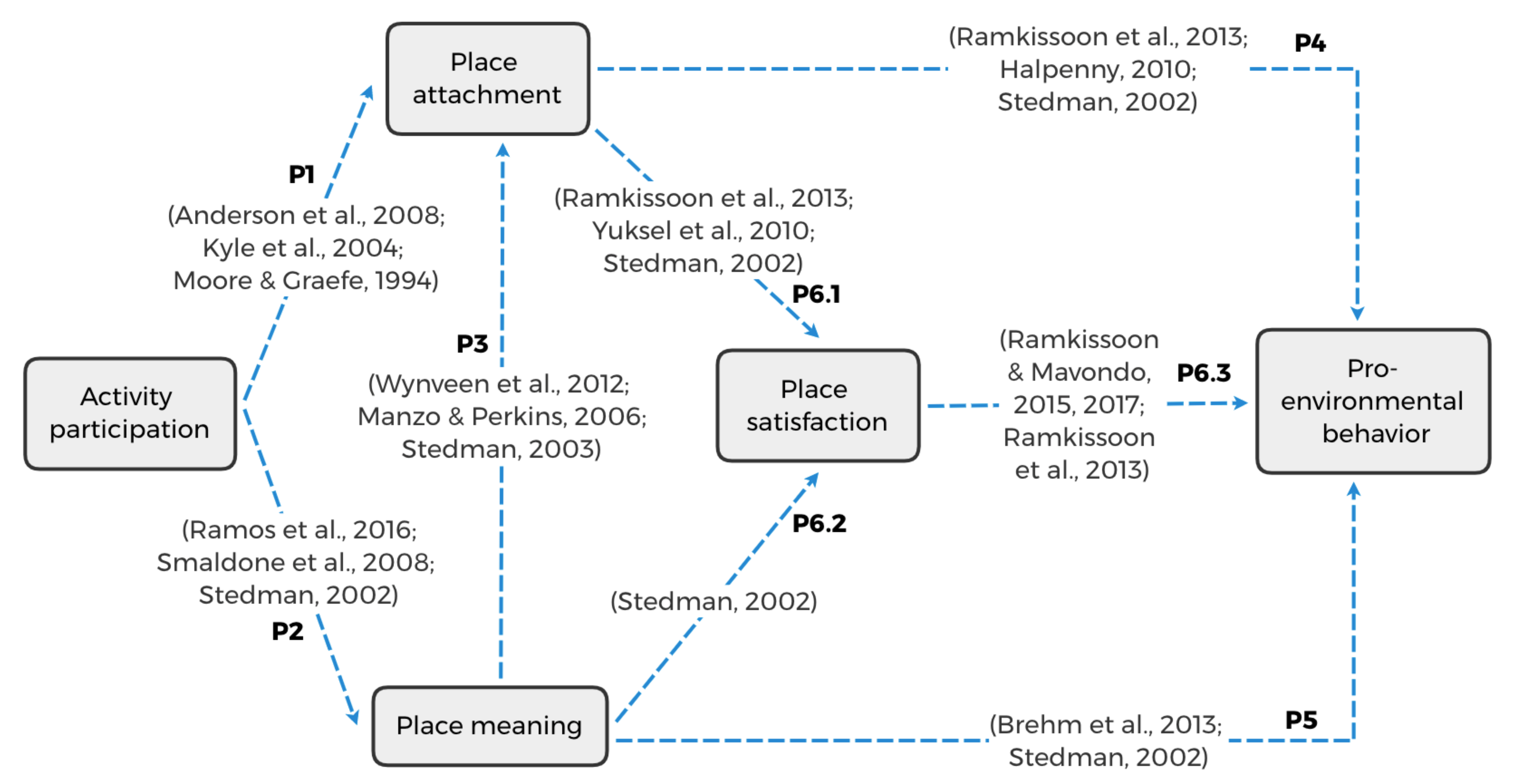

3. The Development of a Conceptual Framework

3.1. Activity Participation in Formulating Attachment and Meanings of Place

3.2. Place Meaning-Attachment Association

3.3. Attachment and Meanings in Promoting Pro-Environmental Behavior

3.4. Satisfaction Plays a Mediating Role between Attachment, Meanings and Behaviors

4. Evaluation Model

4.1. Place Attachment as a Multidimensional Construct

4.2. Place Meaning: A Typology of Perceived Place Values

4.3. Measuring Pro-Environmental Behavior

4.4. Model Testing between Different Groups

4.5. Reinforcement Cycle

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Place Meaning (Wynveen et al. [10], Copyrighted by Elsevier) | Value of Place (Brown et al. [130], Copyrighted by Elsevier) |

|---|---|

Aesthetic beauty

| Aesthetic/scenic value I value these places for the attractive scenery, sights, smells, or sounds. |

Lack of built infrastructure/pristine environment

| Wilderness value I value these places because they are wild. Therapeutic value I value these places because they make people feel better, physically and/or mentally. |

Abundance and diversity of coral and other wildlife

| Biological diversity value I value these places because they provide for a variety of plants, wildlife, marine life, or other living organisms. |

Unique natural resource

| Heritage value I value these places because they have natural and human history. Biological diversity value I value these places because they provide for a variety of plants, wildlife, marine life, or other living organisms. |

Facilitation of desired recreation activity

| Recreation value I value these places because they provide outdoor recreation opportunities. |

Safety and accessibility

| Therapeutic value I value these places because they make people feel better, physically and/or mentally. |

Curiosity and exploration

| Learning value (knowledge) I value these places because we can use them to learn about the environment. |

Connection to the natural world

| Spiritual value I value these places because they are spiritually special to me. |

Escape from the everyday

| Therapeutic value I value these places because they make people feel better, physically, and/or mentally. |

Family and friends

| Spiritual value I value these places because they are spiritually special to me. Future value I value these places because they allow future generations to know and experience them as they are now. |

| Not match | Life Sustaining value I value these places because they help produce, preserve, clean, and renew air, soil, and water. |

| Not match | Intrinsic value These places are valuable for their own sake, no matter what I or others think about them or whether they actually used. |

| Not match | Economic value I value these places for economic benefits such as tourism, forestry, agriculture, and other commercial activity. |

References

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.M.; Eisenhauer, B.W.; Stedman, R.C. Environmental concern: Examining the role of place meaning and place attachment. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stedman, R.C. Toward a social psychology of place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude, and identity. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, L.E.; Shannon, M.A. Getting to know ourselves and our places through participation in civic social assessment. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2000, 13, 461–478. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.T.; Mowen, A.J.; Tarrant, M. Linking place preferences with place meaning: An examination of the relationship between place motivation and place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.L.; Graefe, A.R. Attachments to recreation settings: The case of rail-trail users. Leis. Sci. 1994, 16, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.M.; Henriques, C.; Lanquar, R. Augmented reality for smart tourism in religious heritage itineraries: Tourism experiences in the technological age. In Handbook of Research on Human-Computer Interfaces, Developments, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynveen, C.J.; Kyle, G.T.; Sutton, S.G. Natural area visitors’ place meaning and place attachment ascribed to a marine setting. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Williams, D.R. The meaning of place: Attachments to Femundsmarka National Park, Norway, among tourists and locals. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2002, 56, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Place: An experiential perspective. Geogr. Rev. 1975, 65, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D. A Geography of the Lifeworld; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, D.; Shumaker, S.A. People in Places: A Transactional View of Settings. In Cognition, Social Behavior, and the Environment; Harvey, J.H., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 441–448. [Google Scholar]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B. The people make the place. Pers. Psychol. 1987, 40, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummon, D.M. Community attachment. In Place Attachment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Maes, J. Sustainable development and emotions. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Inclusion with nature: The psychology of human-nature relations. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Is it really just a social construction?: The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammitt, W.E.; Kyle, G.T.; Oh, C.-O. Comparison of place bonding models in recreation resource management. J. Leis. Res. 2009, 41, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment, place identity, and place memory: Restoring the forgotten city past. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. A comparative analysis of predictors of sense of place dimensions: Attachment to, dependence on, and identification with lakeshore properties. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 79, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.E.; Williams, D.R. Maintaining research traditions on place: Diversity of thought and scientific progress. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernandez, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.T.; Absher, J.D.; Graefe, A.R. The moderating role of place attachment on the relationship between attitudes toward fees and spending preferences. Leis. Sci. 2003, 25, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R.; Bacon, J. Predictors of behavioral loyalty among hikers along the Appalachian Trail. Leis. Sci. 2004, 26, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Weber, D. The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kyle, G.; Scott, D. The mediating effect of place attachment on the relationship between festival satisfaction and loyalty to the festival hosting destination. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.D.; Brown, G.; Kim, A.K.J. Measuring resident place attachment in a World Cultural Heritage tourism context: The case of Hoi An (Vietnam). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2059–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.P. The need to ‘belong’: Social connectedness and spatial attachment in Polar Eskimo settlements. Polar Rec. 2014, 50, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Bjerke, T. Associations between landscape preferences and place attachment: A study in Røros, Southern Norway. Landsc. Res. 2002, 27, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsden, B.L.; Stedman, R.C.; Kruger, L.E. The creation and maintenance of sense of place in a tourism-dependent community. Leis. Sci. 2010, 33, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; U of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L.C. For better or worse: Exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion London: London, UK, 1976; Volume 67. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Volume III: Loss, Sadness and Depression; The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis: London, UK, 1980; pp. 1–462. [Google Scholar]

- Halpenny, E.A. Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Akarsu, T.N.; Ageeva, E.; Foroudi, M.M.; Dennis, C.; Melewar, T. Promising the dream: Changing destination image of London through the effect of website place. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 83, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; Van Der Veen, R.; Huang, S.; Deesilatham, S. Mediating effects of place attachment and satisfaction on the relationship between tourists’ emotions and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stedman, R.C. Understanding place attachment among second home owners. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006, 50, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Back, K.-J.; Kim, J.-Y. Family restaurant brand personality and its impact on customer’s emotion, satisfaction, and brand loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Lee, H.Y. Coffee shop consumers’ emotional attachment and loyalty to green stores: The moderating role of green consciousness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C. The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Kobrin, K.C. Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 32, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Bricker, K.; Graefe, A.; Wickham, T. An examination of recreationists’ relationships with activities and settings. Leis. Sci. 2004, 26, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The relations between natural and civic place attachment and pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budruk, M.; Thomas, H.; Tyrrell, T. Urban green spaces: A study of place attachment and environmental attitudes in India. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2009, 22, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L.D.G. Place attachment and pro-environmental behaviour in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenbaum, M.S. Exploring the social supportive role of third places in consumers’ lives. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 9, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.C.; Dwyer, L.; Firth, T. Conceptualization and measurement of dimensionality of place attachment. Tour. Anal. 2014, 19, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, K.S.; Kerstetter, D.L. An interpretation of special place meanings whitewater recreationists attach to the South Fork of the American River. Tour. Geogr. 2002, 4, 396–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment in recreational settings. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.R.; Roggenbuck, J.W. Measuring Place Attachment: Some Preliminary Results; NRPA Symposium on Leisure Research: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. Sense of place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners attitudes toward their properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, B.W.; Krannich, R.S.; Blahna, D.J. Attachments to special places on public lands: An analysis of activities, reason for attachments, and community connections. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2000, 13, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitland, R.; Smith, A. Tourism and the aesthetics of the built environment. In Philosophical Issues in Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berleant, A. Constructing Place: Mind and the Matter of Place-Making; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, A.J. Into the tourist’s mind: Understanding the value of the heritage experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1999, 8, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, K.; Harun, N.Z.; Mansor, M. Place meaning of the historic square as tourism attraction and community leisure space. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 202, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stedman, R.C. Chapter 4-What Do We “Mean” by Place Meanings? Implications of Place Meanings for Managers and Practitioners. United States Dep. Agric. For. Serv. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW 2008, 744, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, K.; Watson, A. Understanding place meanings on the bitterroot national forest, Montana. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 20, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J. Making a city: Urbanity, vitality and urban design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bødker, M.; Browning, D. Beyond destinations: Exploring tourist technology design spaces through local–tourist interactions. Digit. Creat. 2012, 23, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitland, R. Introduction: National capitals and city tourism. City Tour. Natl. Cap. Perspect. 2010, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laarman, J.G.; Durst, P.B. Nature travel in the tropics. J. For. 1987, 85, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, C.-T.; O’leary, J.T. Motivation, participation, and preference: A multi-segmentation approach of the Australian nature travel market. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1997, 6, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, R.E. Studies in Outdoor Recreation: Search and Research for Satisfaction, 2nd ed.; Oregon State University Press: Corvallis, OR, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hammitt, W.E. The familiarity-preference component of on-site recreational experiences. Leis. Sci. 1981, 4, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.K. Visitation to natural areas on campus and its relation to place identity and environmentally responsible behaviors. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Sarmento, E.M. Place attachment and tourist engagement of major visitor attractions in Lisbon. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, D.; Harris, C.; Sanyal, N. The role of time in developing place meanings. J. Leis. Res. 2008, 40, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, T.; Christensen, J.E.; Burdge, R.J. Social groups and the meanings of outdoor recreation activities. J. Leis. Res. 1981, 13, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.; Hodge, I. Clustering visitors for recreation management. J. Environ. Manag. 1984, 19, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hammitt, W.E.; McDonald, C.D. Past on-site experience and its relationship to managing river recreation resources. For. Sci. 1983, 29, 262–266. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, A.E.; Niccolucci, M.J. Place of residence and hiker-horse conflict in the Sierras. In Chavez, Deborah J., Technical Coordinator, Proceedings of the Symposium on Social Aspects and Recreation Research, Ontario, CA, USA, 19–22 February 1992; Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-132. Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service; US Department of Agriculture: Albany, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 71–72. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R.A. Product/consumption-based affective responses and postpurchase processes. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.-Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, H.; Del Bosque, I.A.R. Exploring the cognitive–affective nature of destination image and the role of psychological factors in its formation. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, G.R.; Veloutsou, C. A cross-industry comparison of customer satisfaction. J. Serv. Mark. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, W.; Kalra, A.; Staelin, R.; Zeithaml, V.A. A dynamic process model of service quality: From expectations to behavioral intentions. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Suh, J. Transaction-specific satisfaction and overall satisfaction: An empirical analysis. J. Serv. Mark. 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. Reassessment of expectations as a comparison standard in measuring service quality: Implications for further research. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stern, P. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, A.P.; Rose, R.L. The effects of environmental concern on environmentally friendly consumer behavior: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 40, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivek, D.J.; Hungerford, H. Predictors of responsible behavior in members of three Wisconsin conservation organizations. J. Environ. Educ. 1990, 21, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, J.; Ebreo, A. Emerging Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives on Conservation Behavior. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology; Bechtel, R.B., Churchman, A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 541–558. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Goal-directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B. Measuring environmental behaviour. Environ. Psychol. Introd. 2018, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, A.P.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Selected predictors of responsible environmental behavior: An analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1986, 17, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, M.P.; Ward, M.P. Ecology: Let’s hear from the people: An objective scale for the measurement of ecological attitudes and knowledge. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.T. Social Attitudes and Other Acquired Behavioral Dispositions. In Psychology: A Study of a Science; Koch, S., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1963; Volume 6, pp. 94–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Byrka, K.; Hartig, T. Reviving Campbell’s paradigm for attitude research. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 14, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mónus, F. Environmental perceptions and pro-environmental behavior–comparing different measuring approaches. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 132–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.H.; Fulton, D.C. Experience preferences as mediators of the wildlife related recreation participation: Place attachment relationship. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2008, 13, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.L.; Scott, D. Place attachment and context: Comparing a park and a trail within. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 877–884. [Google Scholar]

- Shamai, S. Sense of place: An empirical measurement. Geoforum 1991, 22, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C.; Perkins, D.D. Finding common ground: The importance of place attachment to community participation and planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2006, 20, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, C.W.; MacInnis, D.J.; Priester, J.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Iacobucci, D. Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, Z.; Soopramanien, D. Types of place attachment and pro-environmental behaviors of urban residents in Beijing. Cities 2019, 84, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mesch, G.S.; Manor, O. Social ties, environmental perception, and local attachment. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T. The satisfaction–place attachment relationship: Potential mediators and moderators. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2593–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T. Proenvironmental behavior: Critical link between satisfaction and place attachment in Australia and Canada. Tour. Anal. 2017, 22, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vorkinn, M.; Riese, H. Environmental concern in a local context: The significance of place attachment. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worster, A.M.; Abrams, E. Sense of place among New England commercial fishermen and organic farmers: Implications for socially constructed environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2005, 11, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.A.; Anderson, D.H. Getting from sense of place to place-based management: An interpretive investigation of place meanings and perceptions of landscape change. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, K.A.; Goodrich, C.G. Making place: Identity construction and community formation through “sense of place” in Westland, New Zealand. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2009, 22, 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, G.K. The habit of tourism: Experiences and their ontological meaning. Contemp. Tour. Exp. Concepts Conseq. 2012, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wearing, B.; Wearing, S. Refocussing the tourist experience: The flaneur and the choraster. Leis. Stud. 1996, 15, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voase, R. Rediscovering the imagination: Investigating active and passive visitor experience in the 21st century. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 4, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerveny, L.K.; Biedenweg, K.; McLain, R. Mapping meaningful places on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula: Toward a deeper understanding of landscape values. Environ. Manag. 2017, 60, 643–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, D.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. From religious belief to intangible cultural heritage tourism: A case study of Mazu belief. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, C.; Gifford, R. The validity of self-report measures of proenvironmental behavior: A meta-analytic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N. Self-reports: How the questions shape the answers. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, S.; Klöckner, C.A. Social desirability in environmental psychology research: Three meta-analyses. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, C.; Sherman, D.K.; Kim, H.S. “Green to be seen” and “brown to keep down”: Visibility moderates the effect of identity on pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C.; Rothengatter, T. The effect of tailored information, goal setting, and tailored feedback on household energy use, energy-related behaviors, and behavioral antecedents. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B.F. Contingencies of Reinforcement: A Theoretical Analysis; BF Skinner Foundation: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, W. Neuronal reward and decision signals: From theories to data. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 853–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, E.W.; Aknin, L.B.; Norton, M.I. Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science 2008, 319, 1687–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasser, T. Living both well and sustainably: A review of the literature, with some reflections on future research, interventions and policy. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 375, 20160369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Webb, T.L.; Sheeran, P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C. The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Activity participation | is comprised of activity types and the time-spent indices in participation [8,35,66,69,75]. |

| Place attachment | is a positive emotional bond between a person and a place [27]. |

| Place meaning | refers to what is attached (the importance-meanings), rather than to how much of it is attached (the bond-attachment) [2,10]. |

| Place satisfaction | is the perceived quality of a place under a multidimensional summary judgment [4]. |

| Pro-environmental behavior | is conscious behavior with the aim of minimizing negative impacts on the environment [89]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dang, N.H.; Maurer, O. Place-Related Concepts and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Tourism Research: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11861. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111861

Dang NH, Maurer O. Place-Related Concepts and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Tourism Research: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):11861. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111861

Chicago/Turabian StyleDang, Nam Hoai, and Oswin Maurer. 2021. "Place-Related Concepts and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Tourism Research: A Conceptual Framework" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 11861. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111861

APA StyleDang, N. H., & Maurer, O. (2021). Place-Related Concepts and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Tourism Research: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability, 13(21), 11861. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111861