Abstract

The routine approach used in risk management is based on the scheme that within the prevention period an organisation or a state prepares for the expected risks and once the risks occur, resources and internal procedures are implemented to mitigate their negative consequences. The objective of the paper is to analyse risk management and its constraints, its application in COVID-19 period and based on it provide mitigating strategies for specific problems/risks related to COVID-19. The research methods related to the topics are: (a) study of books, newspapers and other internet resources and (b) interviews with COVID-19 managers at district and regional level in the north of Slovakia. The proposals for mitigation strategies are based on the basic assumption relevant for COVID-19 that there are risks with unknown probability and unknown consequences. Therefore, the mitigation strategies are adapted to the current situation, which includes lack of data and know-how, lack of experience, political and economic unrest and social problems. The impact of constraints is based on an ad-hoc or unplanned and clearly structured approach. Problems and risks are identified and mitigation strategies are proposed. The proposed measures (quantitative/qualitative) should be evaluated and via benchmarking the development and efficiency of applied measures monitored and assessed. The output of identified risk-known and –unknown creates a framework for implementation.

1. Introduction

The routine approach used in risk management is based on the scheme: within the prevention period, an organisation prepares for the risk and once the risk occurs, resources and internal procedures are prepared to mitigate the negative consequences. The preparation is formally explained in a specific emergency plan that relates to the specific risk, risk events. This plan includes relevant resources, communication and procedures in case of an occurred risk. The contingency plan is therefore a formal document that enables staff to be trained, resources to be allocated and guidelines for risk mitigation activities to be provided (see also [1,2]).

The objective of the paper is to analyse risk management, its application in COVID-19 period and based on it provide mitigating strategies for specific problems/risks related to COVID-19. Meeting the target is conditional:

(a) analysis and discussion of risk management issues, specifically the link between risk and the possibility of quantification, and the availability of data on consequences and likelihood,

(b) the identification of known- and unknown risks for each relevant problem/risk identification, the design of a strategy minimizing negative consequences; this approach constitutes a framework for the application of the management components (central crisis teams) during the COVID-19 period but also in the future when similar unknown risks will attack humanity. I agree with the expression of the reviewer describing the ambition of the paper “…combining a governance related academic article with a policy paper, giving some real guidelines to governing bodies”. It is already apparent that the first industries are reacting quickly to this new situation and adapting their risk management systems [3].

Risk management and business continuity management are approaches used in organisations that are confronted with risks (COVID-19). From the company’s point of view, the pandemic currently being experienced represents a crisis with a so-called “low-probability, high-impact event” that threatens the company’s ability to survive and is associated with a high degree of uncertainty about effects, possible solutions and high pressure to make decisions [4]. Risk management and business continuity management are closely related.

Risk management is usually presented as a process and consists of the following phases: risk identification, risk analysis, evaluation of risk, treatment of risk and monitoring and review the risk.

Business continuity management (BCM) is strategic and tactical capability of the organization to plan for and respond to incidents and business disruptions in order to continue business operations at an acceptable predefined level [5]. BCM lifecycle is the sequence of phases: (1) Understanding the organization, (2) Determining BCM strategy, (3) Developing and implementing BCM response and (4) Exercising, maintaining and reviewing. Within the first phase analytical activities are executed in two steps: business impact analysis and risk analysis. In the second phase there are four strategic models to assure recovery of critical activities in an organization.

Both approaches are based on risk identification and risk analysis and treatment of risk/strategic models. The problem arises when a risk is not foreseen and therefore treatment of risk cannot be planned (see the section on novel risks in this paper).

The typical approach based on the risk management is that after identifying and assessing risks there are applied mitigating strategies. Authors [6,7] proposed application of methods to better understand the risks. In [6] are proposed applications of Bayesian networks, fault trees, extreme value theory and other methods to analyse data. Based on the analysis there are evaluated assumption concerning the future status of risks and this is a basis for proposed mitigating strategies. The authors [7] analyse the economic risks from two the influenza pandemics that represent extremes along the virulence-infectiousness. Both authors and well as others identify risks (known probability and known behaviour/consequences). In this paper, the difference between presented risks (known data, expected behaviour/consequences-see also [1,2,6,7] and the COVID-19 phenomenon with missing data and expected behaviour/consequences is identified. This contradiction is explained in the paper. The theory of risk management and its specific implementation in the COVID-19 period is explained.

There are events like COVID-19 that can be called Black Swan–highly consequential but unlikely events that are easily explainable–but only in retrospect [8]. The other approach (by some business oriented people) is to see COVID-19 phenomena as predictable and therefore boards/state institutions should prepare emergency plans to improve resilience, quick and effective reactions.

Another approach followed in the paper is benchmarking. Benchmarking is a process of measuring the performance of company’s products, services, or processes against those of another business considered to be the best in industry. Benchmarking can be classified as internal/external and process/performance/strategic benchmarking. It can also be applied in the COVID-19 period: Identifying the effectiveness of applied measures, comparing the pandemic situation between states/regions/cities, comparing specific regions/organisations before and after implementing COVID-19 mitigation strategies.

The complexity of the HILP phenomena is also cited in (Horizon 2021)-HILP and their cascading effects raise many challenges for governments, businesses and decision-makers, including defining where the responsibilities lie in preparing for both individual shocks and slow-motion trends (e.g., global warming, tipping points, sea level rise) that tend to increase their magnitude and frequency. The topic is also discussed in [9,10,11]).

The content of the paper addresses risk management and risk categories in relation to available data and consequences. Based on the matching of know-how and applied mitigation strategies, the current COVID-19 approaches are discussed and the relationship between adopted measures to minimise COVID-19 impacts and the risk management framework is identified. The proposed measures (quantitative/qualitative) should be evaluated and via benchmarking the development and efficiency of applied measures monitored and assessed.

The paper consists of two parts-theoretical and applicational (model supporting applications). The theoretical part is in the second chapter of the paper where risks are classified and relations between risk and mitigating strategies are expressed. For the objective of the paper is important to express the ability to forecast novel risks. The fourth chapter has the ambition to specify relations COVID-19 and risk management. In the fifth chapter are identified problems/risks descriptions, risk classification and mitigating strategies. This output is seen as the model for applied measures, approaches of public authorities that are responsible for minimizing COVID-19 consequences in society.

2. Risk and Risk Management

The traditional approach to risk is based on the definition of probability and consequence. This is expressed in a risk map, in which all risks to which an organisation is exposed are graphically represented (see e.g., [12,13,14]). Risks are classified and an organisation (e.g., a company/state) prepares for selected risks in case they occur. The selection of risks depends on assessment and analysis. The authors [15] show that people are more willing to take risks when profit and loss expectations are low, and more likely to reject them when these expectations become higher. In a pandemic, however, the risks and their impact cannot usually be assessed. For practical reasons, one will focus on selected risks that have the highest potential to disrupt important goals/key processes of an organisation. The focus is limited to known and unacceptable risks. Risks that threaten the long-term sustainability of an organisation will be targeted.

There are different types of risk classifications (for classifications see for example [2,16,17,18]), in this paper with reference to the content the following three types are addressed:

- Known risks

- Specific risks

- Novel risks

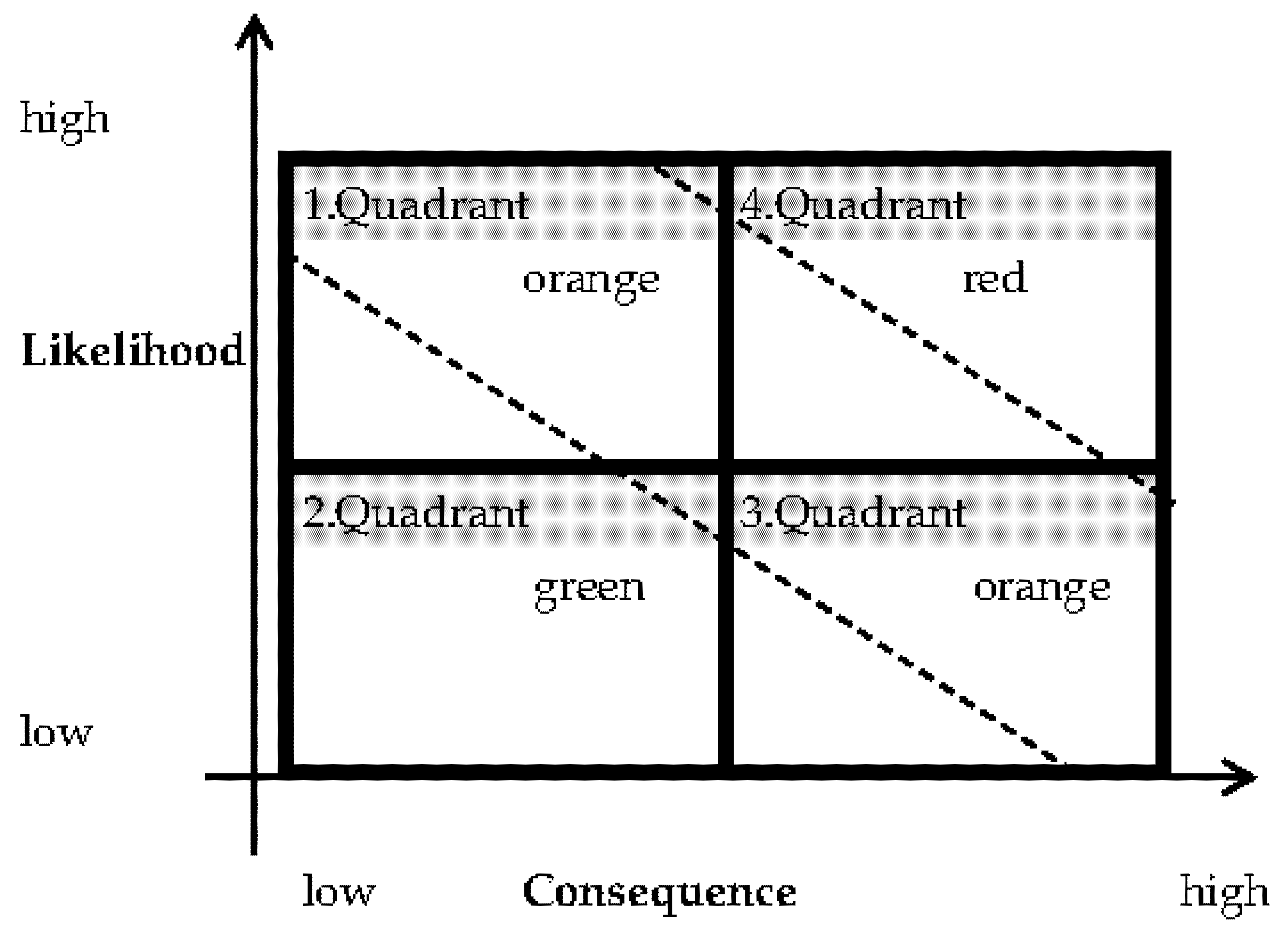

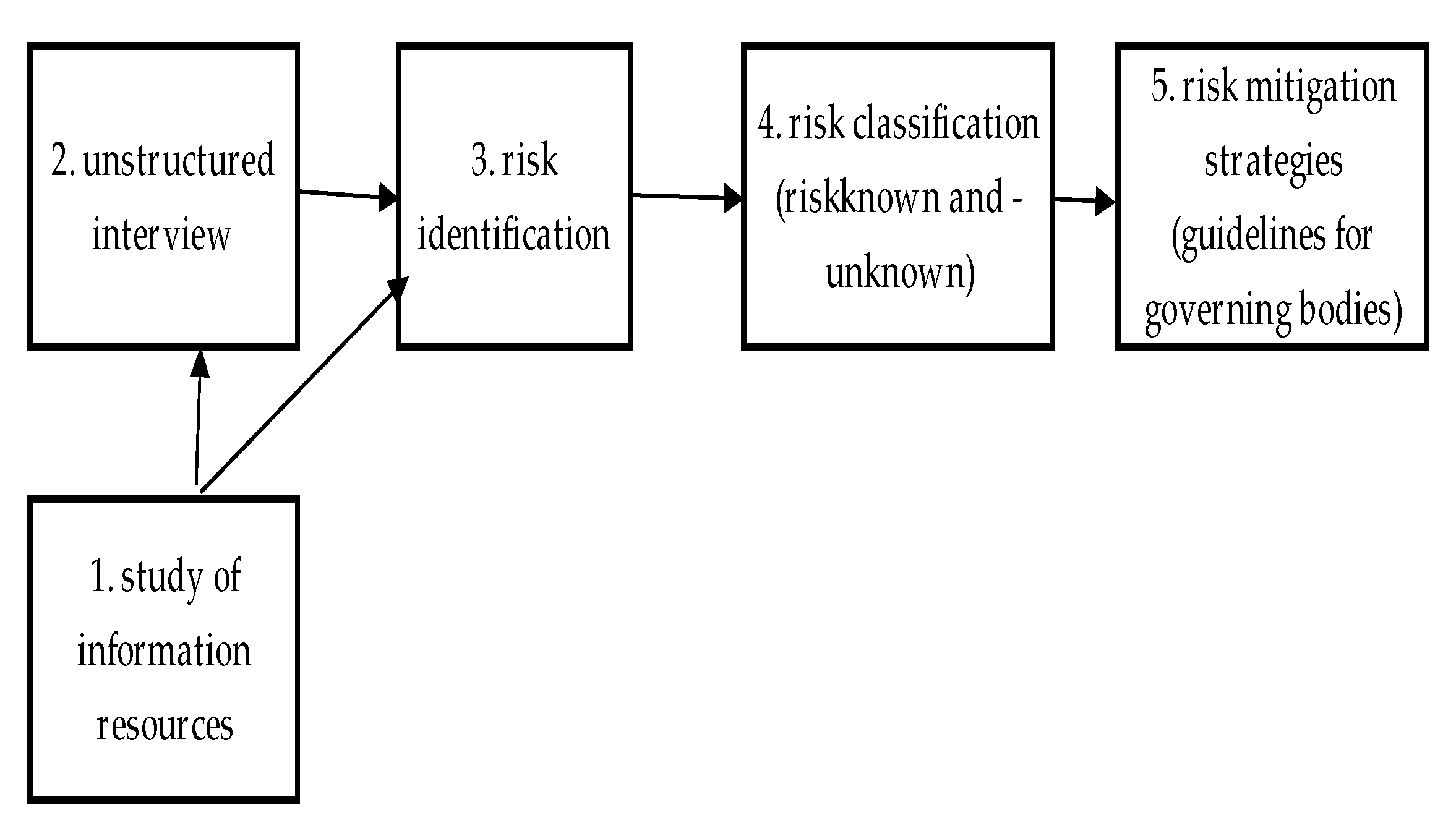

Known risks are risks that have a relatively long history. There are data that allow the probability and consequences to be assessed with reasonable accuracy. In the application of risk management it means that internal norms, procedures are prepared in an organisation. The motive is many years of experience and hard data describing these risks. The position of risks on the risk map is in the orange and green zones (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Risk map.

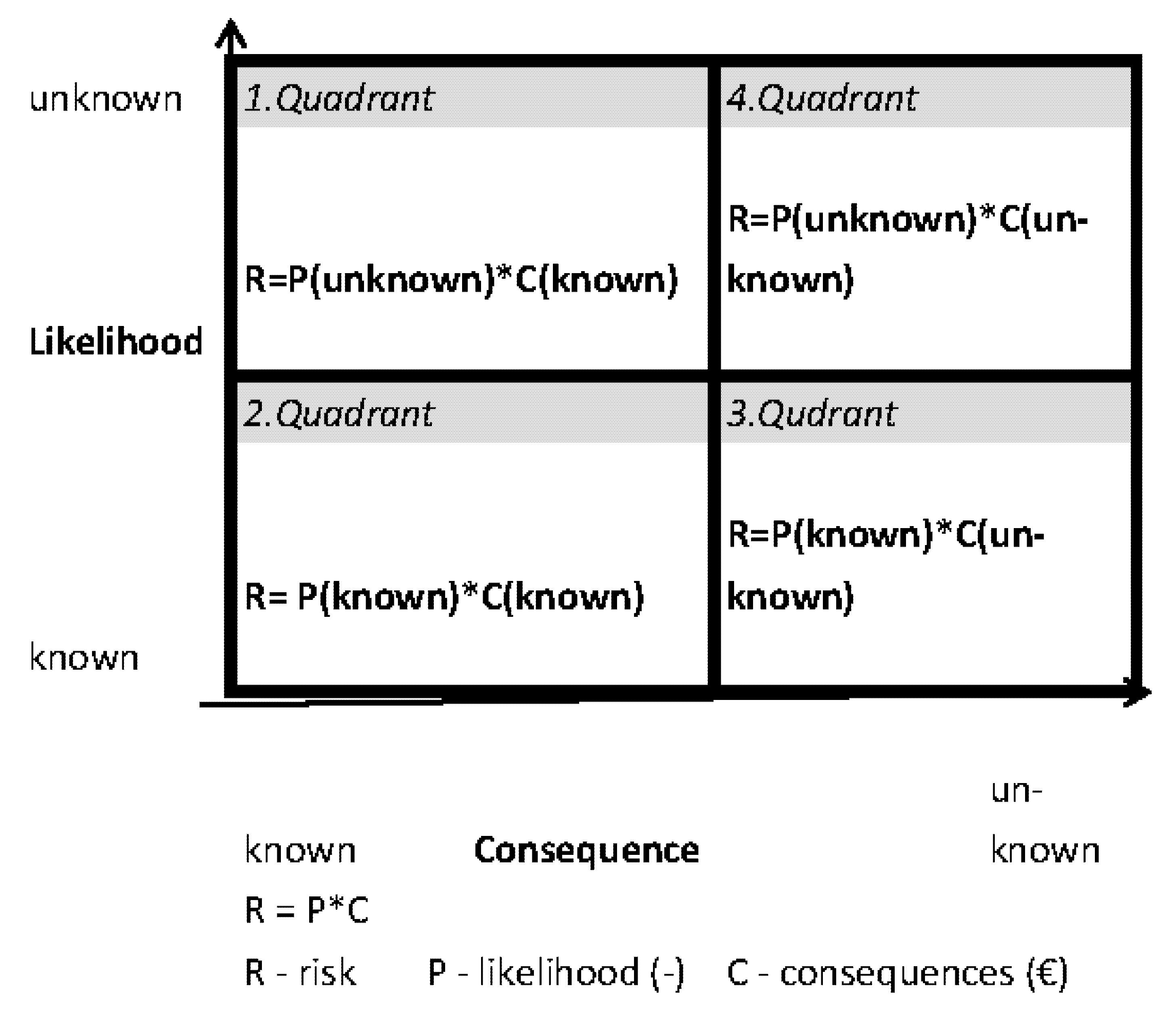

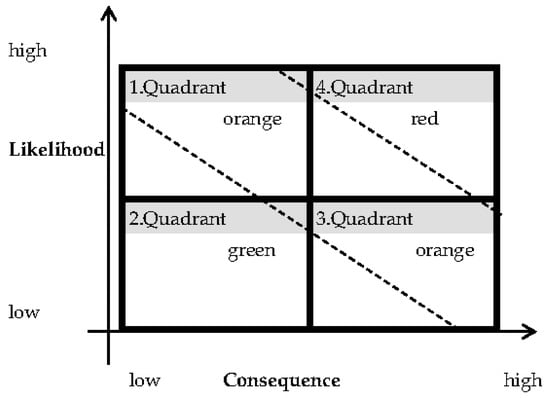

Specific risks are risks with a low probability of occurrence and high consequences. Their position on the risk map is in the 3rd quadrant and on the border between the 3rd and 4th quadrants. The assessment of these risks is based on expert opinions. The risks themselves can be identified by the experts, but the assessment of probability and consequences reflects the lack of data/knowledge from the past. However, internal procedures/norms are formulated for these risks. Considering the knowledge and history of risks (available data), risks can be classified based on the available knowledge/data resources (see Figure 2). Specific risks can thus be referred to as known-unknowns and assigned to the 2nd and 4th quadrants.

Figure 2.

Know-how and data related to risk classification.

Novel risks are described, for example, in the work of [17,18] and also used for this paper. Both the term and the interpretation are somewhat modified here compared to the classic term. In this definition, risks are characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA). In principle, these risks are unexpected and unpredictable. These risks are also referred to as unknown unknowns (see Figure 2). The problem of genuine uncertainty was already described by [19]. This uncertainty is managed by the entrepreneur with judgement. The occurrence of such risks is unique and there is little to no empirical data. Current literature also indicates that various types of uncertainty make it difficult for managers to survive in international business and develop appropriate strategies, especially in the current COVID-19 pandemic [20,21].

The implication of these risks for organizations and their risk management follow:

- there are no specific internal norms/procedures that cover problems related to these risks; (e.g., emergency plan that covers mitigating strategies),

- there are no available resources related to mitigating these risks,

- there is a lack of know-how; the experience is very limited and application of procedures is based on the scheme “learning by doing” or “learning from mistakes” to mitigate consequences,

- after overcoming any specific novel risk all procedures, internal norms will be transferred into the category of known risks or specific risks with all pragmatic consequences for risk management in an organization (COVID-19 is included in this risk category).

In [17], three types of risks are identified that can occur within this category: (a) Black Swan events (threats that one does not know or cannot imagine); (b) Perfect Storm (combined/multiple events, managed failures, the collapse of a system); (c) Mega risks (known risks whose consequences are enormous in their scale or speed).

In [22] describes two risk management approaches applied in banks. They can be assigned as scepticism (focus on trend indicators) and quantitative enthusiasm (focus on risk models and measures).

In this paper, the novel risks associated with COVID-19 are considered next. A very pragmatic and meaningful question follows: Are there approaches that allow an organisation’s risk management to forecast the risk and prepare structures and resources for an appropriate response, with the aim of increasing an organisation’s resilience? This question can be divided into three parts:

- (a)

- are there any methods that allow a risk management staff to forecast novel risk?

- (b)

- what structures are reasonable to reflex new challenges?

- (c)

- what resources must be established (on the place)?

In the case where there is a process to identify the probability and consequence for the identified risk, any risk manager is able to identify relevant activities/strategies to mitigate this risk. But in cases where there is a lack of data (likelihood/consequence), it is almost impossible or only intuitive to implement relevant strategies to mitigate the risk. Due to limitations (lack of data or knowledge), this turns the problem from a clearly formulated problem to an unclear and confusing problem (Figure 1; Figure 2 interrelations).

The broad approach to visualizing risk is published in [23,24].

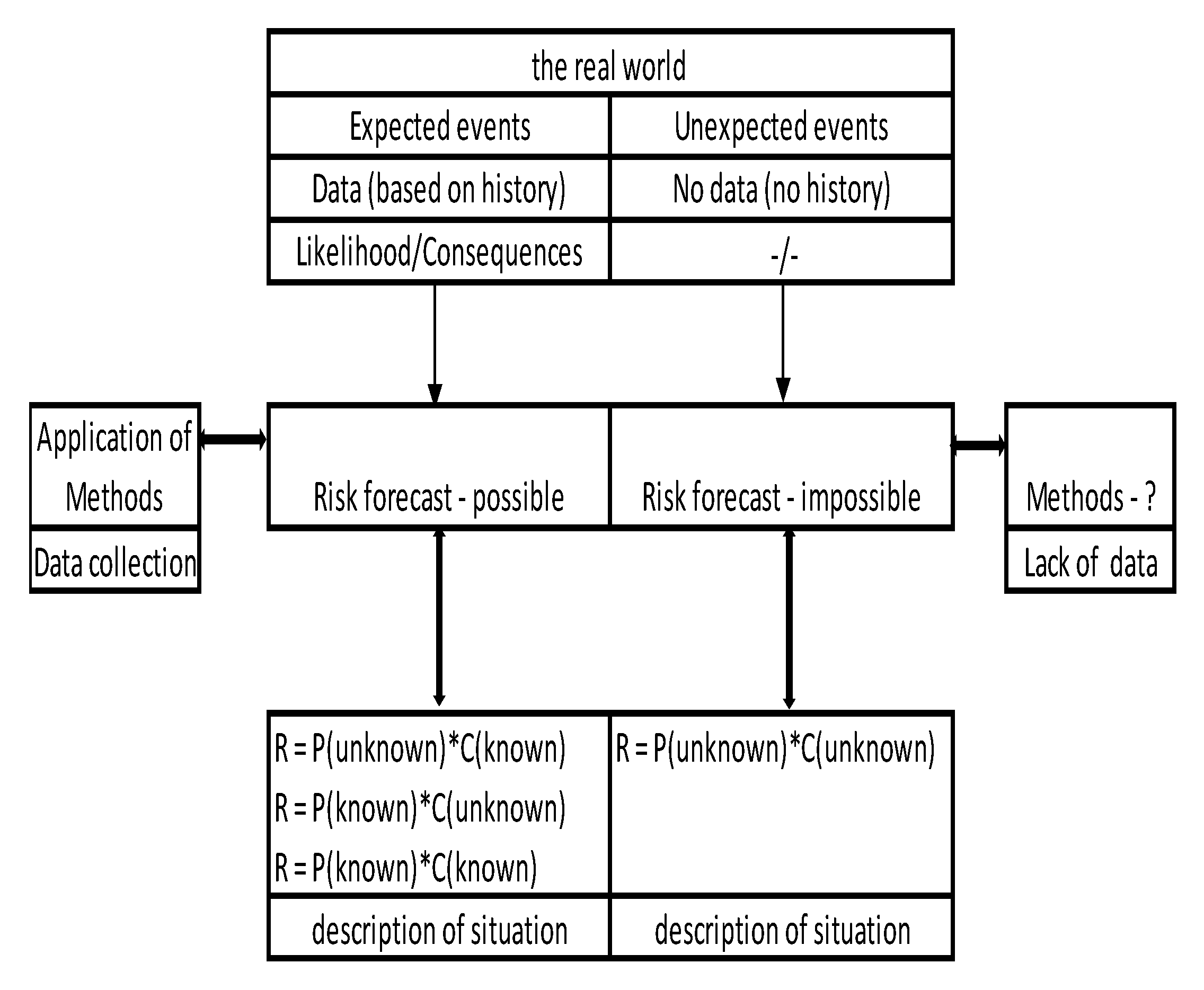

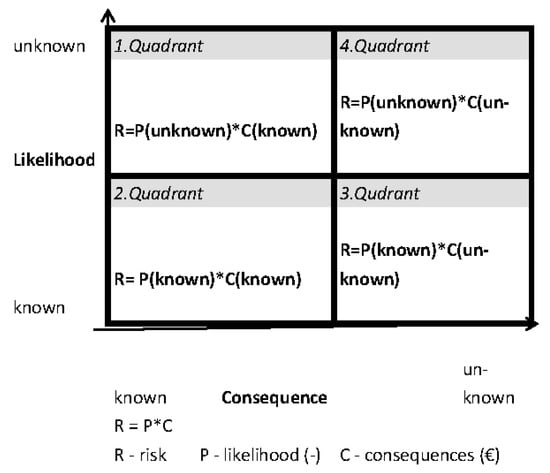

Our knowledge when dealing with the real world is limited–there are unexpected events (based on man–made activities as well as natural factors). The history and repetition of events is the source of data and experience and therefore risks of an event can be forecasted. The novel situation is specific and therefore our knowledge is limited (also characterized by lack of data) and therefore the preparation for the novel risk can be hardly forecasted—see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The concept of the paper.

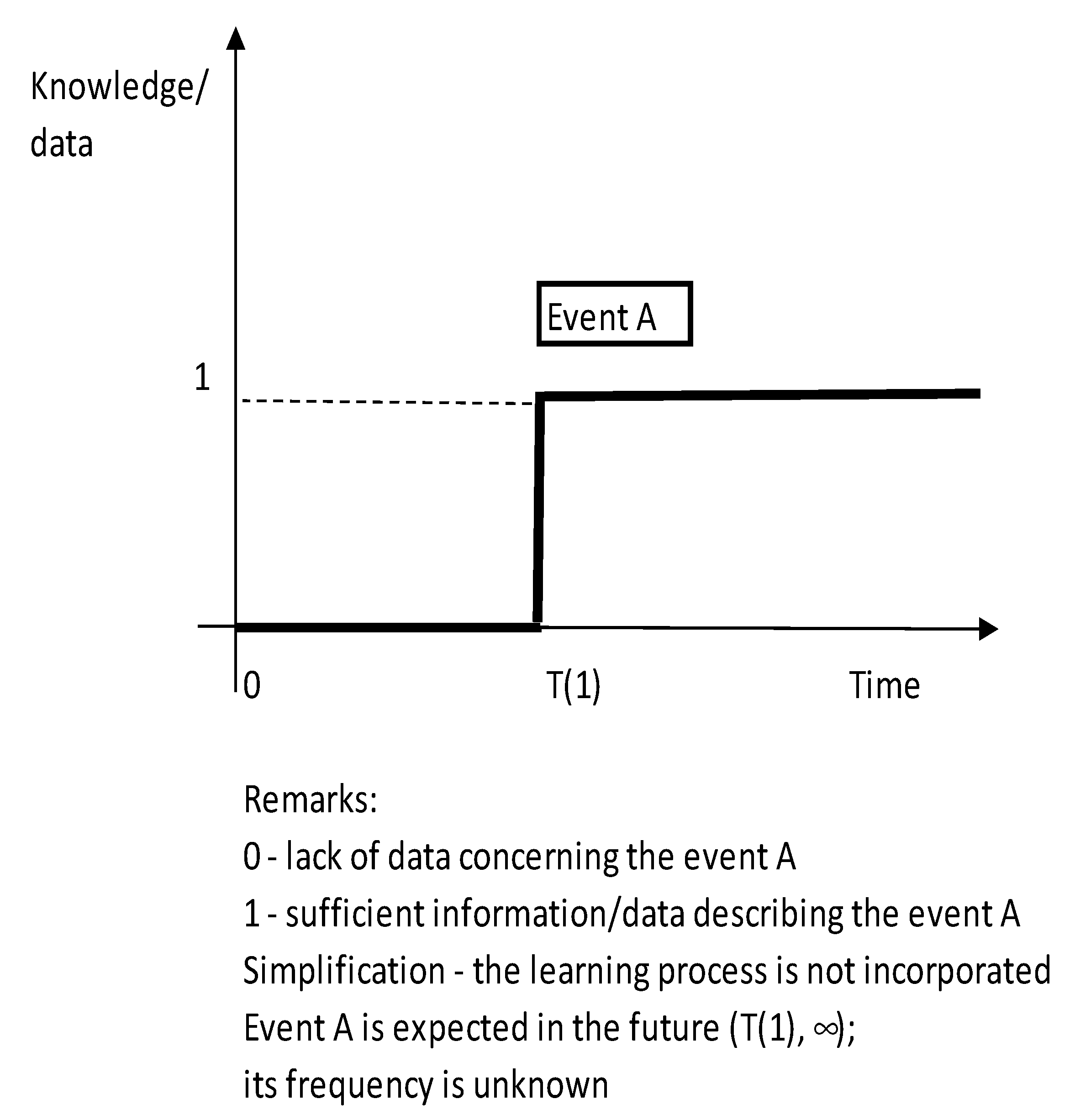

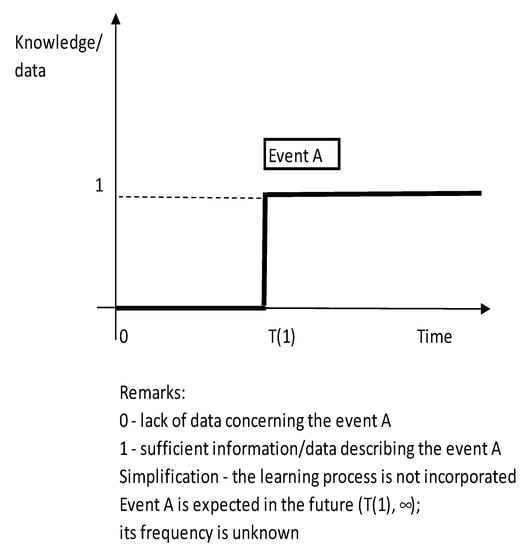

When dealing with knowledge/data the situation of a decision maker can be specified (simplified presentation)—see Figure 4.

Figure 4.

An event and the data/information based on its occurrence.

During time period (0, T(1)) any subject does not have information/data when dealing with the event A. In time period (T(1), ∞) data are available. Based on the frequency and knowledge related to the event A the risk can be expressed and preparation for the risk related to the event A can be specified.

In [22] the author identified three basic features to be able to control risks: first-order risk measurement, second-order risk measurement and risk culture. All these activities provide data/knowledge better understand and be more flexible in managing risks in an organization.

In [24,25] the authors deal with uncertainty and possibility of its quantification. The objective of the study is to specify methods for risk assessment in order to support the decision making process. There are highlighted three features any method should provide:

- How completely and faithfully does it represent the knowledge and information available?

- How costly is the analysis?

- How much confidence does the decision-maker gain from the analysis and the presentation of the results? (This opens up the issue of how one can measure such confidence).

What value does it bring to the dynamics of the deliberation process?

Any method is related to data/specific event–its availability and confidence interrelated to the analysed event.

As the preparedness was limited (and will be similar in the future in the case–novel risk) the approach applied in the Slovak republic should be based on:

- common approaches applied in crisis management,

- communication of heterogeneous teams to support decisions of central crisis management team; the similar organizational structures create on regional and district levels,

- all measures decided to apply by central crisis management team communicate with organizational bodies representing different stakeholders.

3. Research Methodology

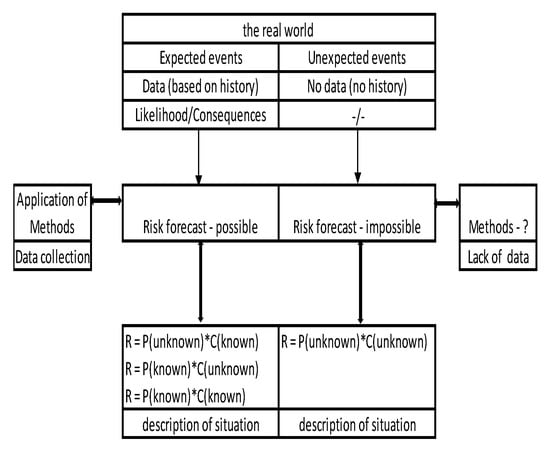

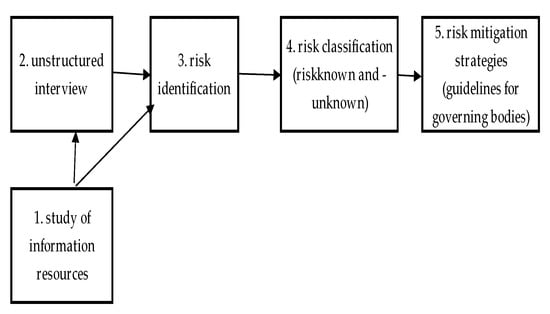

The procedure chosen for this paper is divided into five phases.

- Presentation of the theoretical background on the basis of standard literature

- Gathering data/information through a literature review and interviews

- Risk identification–ex post (based on phases (1) and (2))

- Risk classification (risk known and risk unknown)

- Risk mitigation strategies (guidelines for governing bodies)

The theoretical background is based on the definition of the risk management framework and its application in practice and has been stable for years. There are old and new information resources available dealing with theoretical aspects and applications. A long list of resources relates to this topic. A newer aspect relates to unknown/unknown (probability/consequence) when it comes to applications. a list of resources is rather limited here (see e.g., [2]).

Two main sources were targeted for data gathering: (a) study of books, newspapers and other internet sources and (b) interviews with COVID-19 responsible persons at district and regional levels.

First a literature review was conducted. One part of the review was the search for academic papers. To this, the Scopus database was searched for international academic papers on risk management and COVID. The focus here is on papers with a background in economics. The search syntax for Scopus of the keyword search was as follows: (risk OR risk AND management OR framework) AND (corona OR COVID* OR SARS). The search was conducted at the end of February 2021. The time period was limited to the years 2019 and 2020 in order to exclude contributions with older SARS-CoV from the 2002/2003 pandemic. Furthermore, a filter was placed on the following subject areas, as the content area was narrowed down to Business, Management and Accounting. The restriction to the keywords as well as the refinements in the search lead to 34 scientific paper in the examined area.

Another method used was the application of interviews with qualitative content analysis. The time interval when interviews were performed (a) was during May 2020 to July 2020 and in (b) May 2020 to January 2021.

The 5th steps approach used in the paper—see Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The 5th steps approach applied in the paper.

The context of the proposed procedure can be determined by:

- in the next (possible) wave of COVID-19 risks are already identified and therefore emergency plans, the necessary resources can be forecasted (transfer from novel risk to known risk),

- the phase risk analysis should not be omitted but simplified, to demonstrate not significantly modified virus and expected consequences and/or mitigating strategies.

The sample for unstructured interviews was determined by the identification of responsible organizations for COVID-19 management and willingness and availability of their staff to communicate. As the organizations were identified district and regional institutions and members of crises management team in the hospital. Communication with these staff was face-to-face and via electronic media. Communication in the former was rather limited due to the situation. Therefore, the primary communication was mostly electronic. The unstructured interviews contained the following subjects: situation in the region/organization, factors determining current situation and forecast, managerial structure and communications (strengths and weaknesses), availability of resources to apply mitigating strategies.

4. Practical and Theoretical Aspects of Risk Management during COVID-19

In this part, we will focus on novel risks-claiming to cover the relationship between risk management and the COVID-19 era-as a specific application field of risk management.

4.1. Methods to Forecast Novel Risks

There are three approaches to determining and predicting risks:

- The future is unpredictable; therefore, any attempt to estimate the future is unreasonable. In the book [26] the author expressed his opinion on this problem: “The illusion that we must understand the past goes hand in hand with another illusion that one can anticipate and control the future. These illusions reassure us. They reduce the anxiety we would experience if we allowed ourselves to fully recognize the uncertainty of existence. We all need reassurance that action has reasonable consequences and that wisdom and courage are rewarded with success”.

- The future is predictable as we always can identify causes and consequences; this approach is based on the deterministic behaviour of the world and the ability of analysts to identify all relevant features determining causes and consequences.

- The future is uncertain because of VUCA and the limits of human knowledge.

There are a number of methods used in risk management (see [27]). They can be applied to known risks and to situations with sufficient data to reasonably predict future development/behaviour. Scenario planning is the approach to address the possible/uncertain future. Probability is expressed through expert judgement. Based on scenarios, alternative courses of action/norms, sources for a possible uncertain future can be created. To anticipate this ambiguity, even identified scenarios cannot be considered fixed, therefore creativity should be provided in solving, modifying the prepared norms/procedures. Based on the scenario/type of problem and its real evolution, other experts are included in the crisis management team (as external or internal members) to participate in activities based on the current new risks or on small modifications of the risks previously identified in the scenario planning. The scepticism toward this approach is expressed in the book (Kahneman 2019): “Confidence is a feeling that reflects the integrity of information and the cognitive ease of processing it. It is wise to take the admission of uncertainty seriously, but if someone declares that he is very certain about something, it says in particular that he has constructed a coherent story in his mind, and not that the story is necessarily true”. An ambition to fully cover the complex aspect of risk management the authors in [1] express: “Disaster risk management needs to be based on an understanding of disaster risk in all its dimensions of vulnerability, capacity, exposure of persons and assets, hazard characteristics and the environment”.

Taking into account the organisational structures, it seems reasonable to set up a unit that is continuously responsible for assessing a new risk, new scenarios, with the aim of creating an early warning system in an organisation.

4.2. Organizational Structures and Managerial Bodies

In risk management based on known risks, the aim is to respond efficiently to these risks. It is an activity that refers to established organisational bodies after experiencing these risks, the so-called crisis team. This structure also has other names (see e.g., [17] where the term “Critical Incident Management Team” is used.

This organisational body, established after the identification of the known risk, is responsible for:

- analyse the consequences; for this reason, it is appropriate to include in this structure experts with appropriate knowledge in specific fields,

- to take all necessary measures to mitigate the consequences,

- communicate with the communities,

- identify all stakeholders in order to analyse their objections and take actions based on them,

- promote a culture that accepts the role and actions of the crisis team and

- create networks to collect and synthesise data; decisions should be based on data that provide a “picture” of the short-term evolution and effectiveness of the approved COVID-19 mitigation strategies.

For novel risks, it is important to identify possible consequences of the current state and planned mitigation measures for COVID-19. For this reason, it is important that an organisational unit or body is designated, such as the CEO (company) or the PM (state). He or she should communicate with stakeholders, explain the current situation and justify the steps taken. For this purpose, a communication management system must be introduced.

These recommendations seem naïve and simple, but combined with a high-level political struggle (as was the case in Slovakia), the effects of the turmoil were evident, such as changing regulations with unclear responsibilities, confusing responsibilities of organisations/institutions and approved/recommended strategies against the suggestions of health specialists/virologists, and confusing communication between state and self-governing institutions as well as residents. Therefore, in the next part of the paper, the approach to problem/risk identification and proposed remedial strategies are presented.

4.3. Resources

As in any socio-economic system like an enterprise or a state, there are critical resources:

- employees, inhabitants,

- technology, infrastructure,

- communication systems,

- ethos, culture and

- know-how

- others.

The quality of human resources is based on the uniqueness of theoretical knowledge and available data in relation to an organisation and its environment. The very important assumption is that the environment is dynamic and therefore risk management must understand the key trends in monitoring the specific problem. Key figures should be identified that provide a full spectrum of phenomena with their evolution. Based on the key figures, the effectiveness of the applied measures as well as the targeted communication to experts and non-professionals (public) can be evaluated:

- Technology is seen here as a material source for mitigating negative consequences.

- Communication is one of the most important aspects of managing a crisis. There are some specifics when talking about crisis communication.

- Ethos/culture in the context of the paper is understood as the approach toward negative consequences of pandemics at all levels in an organization. The ethos can unify human resources and positively motivate behaviour that mitigates negative consequences. Ethos in this relationship strengthens the unity of human resources in a positive attitude to applied preventive or reactive measures.

- Know-how is the ability of an organisation/country to develop and implement procedures, material resources (vaccination) to minimise the negative consequences of the pandemic.

4.4. COVID-19 as the Source of Crisis

COVID-19 has created a crisis due to its complex negative impacts. The crisis is not only strengthened by its impact on the health of residents, but its influence is global (geographical) and complex (economic and social). Especially in the economic sphere, COVID-19 has shown how vulnerable both companies and entire societies are through global supply chains [24,28,29].

A crisis is a phenomenon that

- is unwanted,

- complex; crisis management is the application of a set of measures that must respect the constraints of the environment,

- endangers the existence of the system, the fulfilment of its objectives,

- exposes crisis managers to psychological pressure and stress when making decisions in changing conditions,

- depending on the specificity can be global and

- requires the available resources to minimize the causes and consequences of the crisis; these resources are human, technical, financial and other (depending on the nature of the crisis).

The authors [16] lists the key factors influencing the consequences of the crisis:

- scope and complexity,

- diversity of information and information sources,

- diversity of users of information and

- infrastructure status.

Decision-making during a crisis has the following characteristics:

- decision making in stress,

- decision-making under constantly changing conditions, which corresponds to decision-making reactive in the meaning of reacting to the current situation,

- ever-changing conditions create uncertainty in decision-making; uncertainty stems from a lack of data and possible ignorance of the decision-maker (given the lack of experience from past crises) and

- political and social decision-making, which corresponds to the diverse goals of stakeholders.

Decision-making during a crisis is burdened by stress, time pressure and complexity. Its consequences influence the economic, social and political systems of the country.

4.5. Slovakia and COVID-19

In the period March-September 2020, Slovakia displayed a minimal number of deaths and a relatively low number of infections (figures and trends-see [30]) In that period, there was also a change of government-the twelve-year period of social democracy ended. After September 2020 until now, there has been a period of another wave of pandemic, when Slovakia indicated very unfavourable indicators in the number of deaths and infected. The most significant shortcomings can be identified (the intensity of some of them is decreasing over time):

- unclear and constantly changing conditions for citizens, pendlers and businesses,

- missing and unclear border restrictions,

- attitude towards vaccination, implementation of testing has become a subject of political struggle,

- confused communication by political leaders and on the issue of prevention and measures taken,

- the lack of a strategy for a course of action to minimise the impact of the pandemic (availability of medical and economic resources),

- inflexible system of financial support for the population and entrepreneurs,

- the absence of a system of measures for the reception of returning Slovaks from abroad,

- others.

Overall, the system was initially a political agenda, characterised by unpreparedness, improvisation, lack of strategy and incompetent communication.

Further, these rather general items will be specified in the context of COVID-19 and its relation to the risk management framework. There is an ambition, based on the experience from Slovakia, to formulate specific questions that correspond to the theory and its positive or negative applications within the COVID-19 period.

5. Risk Management and the Pandemic Novelty Risk Using the Example of COVID-19

In the USA [31], three steps have been proposed to establish a Business Emergency Operations Centre (BEOC) for response and recovery operations. Table 1 provides a brief description of the steps and relevant activities.

Table 1.

Content of COVID-19 phases.

The problems exploded by COVID-19 have been identified and for each risk/problem a brief description of the applicable mitigating strategy is proposed (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Problem/risk identification and proposed mitigating strategies.

This formal approach highlights the

- presents the alignment of COVID-19 and the risk management framework, and

- propose the framework when dealing with COVID-19.

The proposed mitigating strategies and its efficient applications can be directly or indirectly verified.

The efficient management of governing bodies during COVID-19 period means:

- there are enough capacities to heal COVID-19 patients; this reflects in mortality low rate, low rate of infected; the measures should be compared (benchmark) to other countries;

- qualitative measures describe the efficiency of cooperation all relevant bodies-political representatives, health care facilities, community facilities and institutions, that support mitigating strategies;

- in cases related to communications or other activities based on risk unknown event there should be proposed time scales/objectives and crisis teams should control their fulfilment;

- one of the most crucial aspect during COVID-19 is to establish competencies of governing institutions; the strategy should be clearly

- formulated with competencies of major players; based on the experience there can be positions and competencies modified (ideally as the consensus of all stakeholders);

- to apply measures, to identify effectiveness of measures with data/models should be one of the crisis team’s major objectives; existing and new models for forecasting should be permanently evaluated and if necessary modified.

The applied mitigating strategies therefore create a framework for activities of crisis teams and all relevant stakeholders during COVID-19 period not only in Slovakia but also in other countries. The two risk categories provide source on which public authorities/stakeholders can prepare for the future within the phase prevention/planning and ad hoc approach based on existing situation.

The problems/risks presented in Table 2 represent the classification of core problems identified during the COVID-19 period in Slovakia. Mitigation strategies should be elaborated in detail, taking into account various aspects relevant to a state, the level of development, political status, culture and also the level of development of health infrastructure.

6. Conclusions

In the paper we have formulated the most important risks of an organisation/a state and proposed a mitigation strategy in terms of a framework. The framework is based on the approach implemented in the Slovak Republic. List of problems/risk descriptions is based on: interview with the state representatives, the community representative; different local media (electronic, paper) and social media.

The idea of the paper was to present the relationship of COVID-19 consequences with the risk management framework. Based on the analysis, it can be stated that the novel risk has limitations in the prevention phase. The focus should be on the application of the risk management framework and specific countermeasures recommended by health policy makers. As the novel risk cannot be reasonably predicted (unknown-unknown), the current only approach is to adapt quickly and apply cooperation and creativity as a response. The learning effect should be incorporated into the approved measures for potential future incidents [1] to build a more resilient EU after COVID-19 (or any other unknown risks). In any case, challenges for disaster risk management are emerging.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 period, Slovakia lacked any data, institutions/crisis teams were not prepared/resources were not available. The further management approach was based on “common sense” and “learning by doing”. After 1 year of experience, the actual state can be transferred through problem/risk description and assignment of proposed mitigation strategies. These strategies can be applied in the future (if needed) and the so-called “bounce-back” effect will be robust to increase the resilience of the state/municipality/organisation.

For complex phenomena (like GDP/profit) forecasting is applied scenario analysis method. The principle is based on identification of relevant variables and its impact on output. Applied method is based on variations of relevant input variables and quantification (via model) of them to output. The method however cannot be applied for COVID-19 forecasting in the incubating phase (or any other pandemic in the future). The reason is the lack of know-how and data providing more in-depth knowledge of the phenomena.

The preparation for novel risk is limited. The only solution is adaptation of tailor-made measures that correspond to current status of know-how. To support that communicated measures should be created/implemented and verified in practice.

The content of the paper reflects the ambition of EU to the unknown risks and their consequences–to get the right balance between planning for specific “known” events and creating generic responses for events that are rare or unexpected, research should support the anticipation and management of shock events through improving planning processes, establishing broader risk-uncertainty frameworks that capture such events, enhancing business resilience and responses to shocks, and stepping up communications in crisis (Horizon 2021). The output represents a model that can be implemented for the event identified as HILP-COVID-19. The model presents a summary of activities that, if implemented and evaluated for effectiveness, can reduce the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors present a tool for the implementation of the measures by relevant organizations/entities. The idea of the paper corresponds to the content of [32], but here the measures are reduced to universities in China. The authors’ ambition was to provide a proposal of strategies that will minimize the impact of the pandemic in the state/region.

The content of the paper can be applied in future research, for example in the analysis of specific risks and the assessment of specific measures to mitigate them. The limitation of the study is the rather narrow sample (Slovakia) and the limited list of problems/risks. The content also does not cover the broad topic of vaccination (also called vaccination diplomacy).

Author Contributions

J.K. writing—original draft administration worked on the introduction and theoretical framework and revised the whole paper; R.G. literature research on risk management and COVID-19 and preparation; revised the paper; J.R. risk identification and COVID-19 discussion; supervised the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the representatives of local a regional authorities responsible for crisis management for their willingness to communicate to the subject.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Casajus Valles, A.; Marin Ferrer, M.; Poljanšek, K.; Clark, I. (Eds.) Science for Disaster Risk Management 2020: Acting Today, Protecting Tomorrow, EUR 30183 EN; JRC114026; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-18181-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 31000:2018(en) Risk Management—Guidelines. 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-2:v1:en (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Tullo, L. COVID-19 triggers great nonfinancial risk crisis: Nonfinancial risk management best practices in Canada. J. Risk Manag. Financ. Inst. 2021, 14, 40–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, C.M.; Clair, J.A. Reframing Crisis Management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiles, A. The Definite Handbook of Business Continuity Management; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-67014-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, B.K. Scenario Analysis in Risk Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-25056-4. [Google Scholar]

- Verikios, G.; Sullivan, M.; Stojanovski, P.; Glesecke, J.; Woo, G. Assessing Regional Risks from Pandemic Influenza. The World Economy; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; Volume 39. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, N.N. The Black Swan; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4000-6351-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mondragon, A.E.C. The Effects of Low-Probability, High-Impact Events on Automotive Supply Chains: Black Swans and the 2011 Earthquake-Tsunami Disaster that Hit Japan. In CEC Sustaining Industrial Competitiveness after the Crisis: Lessons from the Automotive Industry; Japan External Trade Organization: Tokyo, Japan, 2012; pp. 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, Y. Strategies for Managing Low-Probability, High-Impact Events. In Learning from Megadisasters; Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake; World Bank: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Wurster, S.; Klafft, M.; Fuchs-Kittowski, F. High Impact–Low Probability Incidents at a Coastal Metropolis: Flood Events and Risk Mitigation by Crowd-Tasking Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Disaster Management (ICT-DM), Vienna, Austria, 13–15 December 2016; pp. 207–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sartor, F.J.; Bourauel, C. Risikomanagement Kompakt; Oldenbourg Verlag München: München, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3-486-70810-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rebooting Risk Management, Deloitte Insights. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/economy/covid-19/risk-management-during-covid-19.html (accessed on 4 October 2020).

- Bromiley, P.; Rau, D.; McShane, M.K. Can Strategic Risk Management Contribute to Enterprise Risk Management? A Strategic Management Perspective; Finance Faculty Publications: California, CA, USA, 2015; Volume 3, Available online: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/finance_facpubs/3 (accessed on 2 October 2021).

- Bouchouicha, R.; Vieider, F.M. Accommodating stake effects under prospect theory. J. Risk Uncertain. 2017, 55, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehrotra, S.; Znati, T.; Craig, W. Thompson: Crisis Management. IEEE Internet Comput. 2008, 12, 14–17. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/3420014_Crisis_Management (accessed on 3 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Leonard, H.B.; Mikes, A. Novel Risks, Working Paper 20-094, Harvard. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=57892 (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Kaplan, R.S.; Mikes, A. Risk Management—The Revealing hand. Working Paper 16-102, Harvard. 2016. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/16-102_397b963b-1a8b-4dcf-942f-e45acc8c9e96.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2020).

- Knight, F.H. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership, Abstract. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1496192 (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Sharma, P.; Leung, T.Y.; Kingshott, R.P.J.; Davcik, N.S.; Cardinali, S. Managing uncertainty during a global pandemic: An internationals business perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, D.W. Uncertainty and Risk Are Multidimensional: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Public Policy Mark. 2021, 40, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikes, A. From Counting Risk to Making risk Count; Working Paper 11-069; Harward Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; Available online: www.hbs.edu/ris/Publications%20Files/11-069.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Roth, F. Visualizing Risk. Research Collection; ETH Zurich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, N.; Zio, E. Uncertainty Analysis in Fault Tree Models with Dependent Basic Events. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 1146–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- ISO 31010:2019 Risk Management–Risk Assessment Techniques. 2019. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/41536420/ISO_31010_2019_Risk_management_-Risk_assessment_techniques_Management_du_risque_-echniques_dappr%C3%A9ciation_du_risque (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Kahneman, D. Myslenie Rýchle a Pomalé (Thinking: Fast and Slow); Aktuell: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2019; ISBN 978-80-8172-056-7. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC Guide 51:1999, Safety Aspects–Guidelines for Their Inclusion in Standards. 51:1999. Available online: http://www.electropedia.org/iev/iev.nsf/display?openform&ievref=351-57-03 (accessed on 4 October 2020).

- Fonseca, L.M.; Azevedo, A.L. COVID-19: Outcomes for Global Supply Chains. Manag. Mark. 2020, 15, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derevyankina, E.S.; Yankovskaya, D.G. The impact of Covid-19 on supply chain management and global economy development. Int. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2020, 9, 765–774. [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the Slovak Republic. Available online: https://korona.gov.sk/en/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Business Emergency Operations Center (BEOC) Quick Start Guidence for COVID-19 Response and Recovery. 2020. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_covid_bp_business-emergency-operations-quick-start-guidance.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Chuanyi, W.; Zhe, C.; Yue, X.-G.; McAleer, M. Risk Management by Universities in China. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).