Abstract

Global policies such as the recent ‘Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework’ call for a profound transformation in refugee response. To this end, collaboration with non-traditional humanitarian actors, particularly the private sector has been advocated. The application of new multi-stakeholder partnerships that transcend traditional dyadic relationships have been commended by practitioners for their ability to create stable services and markets in refugee camps. However, the adaptation of multi-stakeholder partnership models to the novelties of refugee response and the dynamics among partners in these complex arrangements requires more attention. This paper explores how the creation and development of multi-stakeholder partnerships can maximize the transformational potential of collaboration for refugee response, ensure the stakeholder diversity needed to provide basic services on a stable basis, and provide a facilitation function that supports the partnership. Using an action-case methodology, the focus of the article is on the Alianza Shire, Spain’s first multi-stakeholder partnership for humanitarian action, which was established to provide energy to refugee camps and host communities in refugee camps in northern Ethiopia. Our findings suggest that (i) the active participation of aid agencies in the co-creation process of a multi-stakeholder partnership may increase the transformational potential of refugee response, (ii) feedback loops and the consolidation of internal learning are essential practices for the effective management of complex multi-stakeholder partnerships, and (iii) the facilitator plays a critical and underexplored role in refugee response collaborative arrangements. In addition, sustainability-oriented university centers may possess a particular capacity for nurturing the transformational potential of multi-stakeholder refugee response partnerships by generating ‘safe spaces’ that foster trust-building, providing a cross-sector ‘translation’ service, and affording the legitimacy and expert knowledge required to conduct learning processes. We believe that the theoretical and practical implications of our research may contribute to the effective fulfilment of the Sustainable Development Goals, specially, SDG7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG17 (Partnership for the Goals).

1. Introduction

Refugee response is currently undergoing a profound transformation. This change has been boosted by the 2016 New York Declaration and its promotion of the ‘Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework’ (CRRF), a global policy that aims to ease pressure on countries that welcome and host refugees, build self-reliance, expand access to resettlement in third countries and other complementary pathways, and foster conditions that enable refugees to return voluntarily to their home countries [1]. Collaboration with non-traditional humanitarian actors, particularly the private sector, has been advocated by the CRRF as a lever to attract knowledge, resources, and wider public attention to achieve its objectives [2,3,4]. As this collaborative approach is being applied in the field, practitioners have highlighted its ability to create stable markets and basic services supply in refugee camps, especially where boundaries between humanitarian and development contexts are blurred [3,5,6].

Multi-stakeholder partnerships are regarded as fundamental to the transformation called for in the UN 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals [7,8]. At the same time, interest in the application of partnerships in humanitarian logistics has grown [9,10,11,12,13], particularly in relation to the exploration of motivations for partnering and outcomes in different contexts [14,15,16,17,18,19]. However, the adaptation of multi-stakeholder partnership models to the new trends of refugee response, and the dynamics among partners in these complex and diverse arrangements, requires more attention [5,6,20].

Due to its cross-cutting nature and impacts, access to energy in refugee camps provides a useful field in which to examine multi-stakeholder collaboration. As well as being one of the leading sectors to implement the CRRF, international initiatives such as the Clean Energy Challenge and the Global Plan of Action for Sustainable Energy Solutions in Situations of Displacement are promoting holistic approaches to energy access in refugee camps using multi-stakeholder collaboration to foster more inclusive planning [21] and to shape market-based strategies [22,23,24]. However, while current research is focused on the technological and service innovations that multi-stakeholder collaborations can enable in access to energy in refugee camps, deeper analysis of the dynamics of these partnerships and how they are orchestrated is scarce [25,26,27,28,29].

This paper explores some of the factors that appear to affect the effective creation and development of multi-stakeholder partnerships for refugee response. To do this, an examination of how partners interact and the facilitation function that supports this is provided using the case of the Alianza Shire, Spain’s first multi-stakeholder partnership for humanitarian action. The Alianza Shire was established in 2014 to provide access to energy in refugee camps and host communities in the Shire region of northern Ethiopia. The partnership includes two private companies (Iberdrola and Signify), a corporate foundation (Acciona.org Foundation), the Spanish Aid Agency (AECID), and an academic institution (Innovation and Technology for Development Centre at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, itdUPM) that acts as an intermediary or facilitator between the different partners. Close relationships also exist with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), local agencies, and NGOs.

The Alianza Shire was established following preliminary studies conducted by the AECID and itdUPM. Between 2016 and 2017, a pilot project took place that benefited 8000 refugees and worked to provide energy services to the Adi Harush camp in the Shire region of northern Ethiopia. The project’s achievements included four kilometers of street lighting with 64 lampposts, and improvements to the electrical grid that enabled the connection of eight communal services and the training of 19 refugees in electrical maintenance. The pilot project had a significant impact on the Adi Harush refugee camp. In addition to a 60% drop in incidents such as night burglaries and an annual saving of 1500 tons of firewood for cooking, a reduction of 2000 tons per year in CO2 emissions was coupled with savings of 30,000€ per year in the diesel required for camp operations. As a result, the Alianza Shire extended its operations to the other four refugee camps in the Shire region and their host communities, as well as to the Somaliland region. The current aim is to reach 40,000 refugees and host community members with exploration of innovative energy supply models such as micro-entrepreneur networks and energy communities, and the provision of a prototype experience in the context of the CRRF.

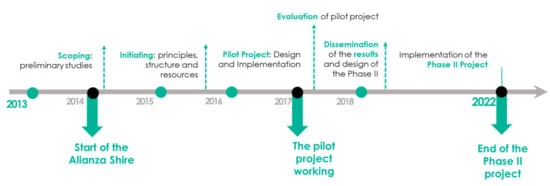

Figure 1 shows an outline of the chronological evolution of the Alianza Shire.

Figure 1.

Alianza Shire timeline.

Our paper examines the formation stages of the Alianza Shire in a partnership lifecycle framework. As some of the authors have been actively involved in the creation and development of the Alianza Shire, particularly undertaking a facilitation function, the paper uses an action-case methodology, and builds upon preliminary studies conducted by the authors (see Appendix A). The paper aims to contribute to the research on multi-stakeholder collaboration in humanitarian logistics [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]; particularly, the research adopts a life-cycle perspective and aims to contribute to the stream of research devoted to exploring the key elements associated to the establishment of transformational collaborations [7,8]. The findings offer practical insights on the effective formation of refugee response partnerships among different actors seeking to provide basic services and market integration. These insights include the importance of exploring the role that aid agencies can play as active co-creation agents; the intrinsic complexity and diversity that this kind of partnership may encompass; the adoption of feedback loops as a way of effectively managing partnership learning, and the role that sustainability-oriented university centers may play in facilitating these partnerships. The ultimate aim of our action research is to endorse successful achievement of the SDGs, particularly SDG7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG17 (Partnership for the Goals), and to propose lessons for their application in practice. Moreover, the research seeks also to contribute to the goals of the Clean Energy Challenge and other international initiatives in energy access related to refugee response.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a theoretical overview for the focus of the research and the application of a partnership life cycle framework. Section 3 presents the research approach. In Section 4, a detailed analysis of the formation phases of the partnership life cycle is offered with discussion of their applicability to the Alianza Shire case study. Key conclusions and lessons are presented in Section 5. The final section, Section 6, includes suggestions for further research.

2. Theorical Overview

2.1. Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration in Refugee Response

In academic literature, collaboration with the private sector has been credited with promoting effectiveness, efficiency, and innovation in refugee response [9,10,11,12,13]. Humanitarian partnerships involving the private sector have focused on the motivations for partnering [16], including efficiency [12,30,31,32,33], pressure from donors [33,34], the expansion of corporate social responsibility policies [35,36], and the learning that corporate actors find in the humanitarian sector, notably when seeking to develop stable relationships with key stakeholders in order to deal with high levels of uncertainty [10,13,37,38,39].

Partnerships with the private sector are further reinforced by the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which adopts a more complex and richer view of cross-sectoral collaborations and stresses the importance of knowledge transfer and capacity building [6]. To develop appropriate effective collaborative arrangements, a better understanding of the motivations for humanitarian and non-humanitarian actors to embrace partnering work and the most suitable partnerships configurations have been called for [16]. Expanding on the notion of shared value developed by Porter and Kramer (2011) [40], Austin and Seitanidi (2012) [41,42] provide valuable insights regarding the incentives that non-profit and corporate actors may find through sustained co-creation of different sources of collaborative value. These include associational value (higher visibility, public awareness, or reputation); transferred value (complementary resources and support, competitiveness); interaction value (trust, opportunities for learning, relational capital), and synergistic value (innovation, internal change, distributed leadership, influence).

According to the 2016 International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC) World Disasters Report [43], most experiences of collaboration in the humanitarian sector to date have involved bilateral relationships between the private sector and humanitarian actors; e.g. International Red Cross (IRC) and Intel [44]; TNT and the World Food Program (WFP) [19,45], DHL and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) [36], or IKEA and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) [5]. The Report further notes that ‘traditional’ private sector partnerships have been mainly short-term, ad hoc, and oriented towards emergency responses that primarily seek to draw on financial support from the corporate sector [43]. They have been also focused on a business-humanitarian supplier-client basis [5] and have mostly been oriented on technological products [46,47]. The collaboration between academia and humanitarian actors has also followed these patterns, being characterized by a short-term technological orientation and a lack of clarity regarding partnering motivations [48].

To effectively and holistically address refugee response, broader collaborative mechanisms that encompass the perspectives, resources, and competencies of multiple players from different sectors, including those of public agencies (from both donor and host countries), companies, the UN system, academia, and NGOs are required [11,16,49,50,51]. The 2030 Agenda describes these relationships as “multi-stakeholder partnerships” [52].

According to Pascucci (2021) [5], new trends are emerging in refugee response that put less emphasis on the material dimension of aid, reinforce the integration of displaced people in local and regional markets [53,54,55], and center on the provision of stable services [20,46,56]. Pascucci (2021) describes a ‘‘de-materialization of refugee aid, namely a tendency to move away from provisions of material relief […] to privilege beneficiaries’ access to local and transnational service markets, and their economic activation and self-reliance”, which require new and more nuanced multi-stakeholder arrangements [5]. In this endeavor, aid agencies are playing a new convening role “shaping […] logistics operations in hybrid markets characterized by blurred boundaries between the private and the humanitarian sector” [5].

Due to its complexity and multidimensional linkages with issues such as protection, health, gender, education, income generation, and the environment [57], access to energy in refugee camps provides an illustrative example of the “de-materialization of refugee aid” [5]. The emphasis here is on addressing concerns in an integrated manner and developing energy solutions that encompass the different needs of users [58]. To ensure provision of safe access to energy in refugee camps, collaborative arrangements are required [59]. In this regard, as well as involving private sector actors, the promotion of policies that facilitate multi-stakeholder partnerships have also been called for [60]. These approaches are viewed as enabling more inclusive planning and design approaches [21] and market-based strategies that promote access to energy in fragile places so that they are perceived as more effective and durable [22,23,24]. In spite of these calls, however, a collaborative approach to energy access for refugees has been hampered by a lack of practical experience in this field and limited theoretical guidance on how to orchestrate the diversity of actors necessary for moving from a product provision focus to one of service provision [57].

2.2. Partnership Lifecycle Approach

As noted above, a deeper understanding of the dynamics involved in the formation and consolidation of multi-stakeholder partnerships for refugee response is needed, particularly in relation to the ingredients that encourage partnerships to adopt bolder and more transformational positions in the provision of unattended access to markets and services [5,46,56]. Austin and Seitanidi (2012) suggest that transformational collaboration is aimed at creating large scale societal benefits through “disruptive social innovations” [61], not just in terms of an external impact dimension, but also in terms of changing “each organization and its people in profound, structural, and irreversible ways”, even to the extent of sometimes creating “an entirely new hybrid organization” [41,42]. Some of the pointers proposed for analyzing the transformational character of a partnership include organizational engagement (level of engagement and importance to mission); resources and activities (type and magnitude of resources, scope of activities, managerial resources); partnership dynamics (interaction, trust and internal change), and impact (co-creation of value, innovation, and external system change) [40].

According to Selsky and Parker (2005), most researchers agree on the usefulness of examining partnerships using a lifecycle approach [62]. Such an approach can also enable the identification of the ingredients that may lead to more innovative and transformational collaborations [41]. Although other partnerships assessment methods have been proposed, namely ‘Collective-Conflictual Value Co-creation’ [63], ‘Partnership Outcomes Assessment’ [64], ‘Partnership Performance Assessment’ [65], and the ‘Strategic Scoping Canvas’ [66], a partnership lifecycle approach enables a more holistic and systematic exploration of a partnership [67]. Furthermore, by examining factors that affect each stage of a partnership’s life cycle, critical lessons can be extracted to improve partnership planning and forecasting [62].

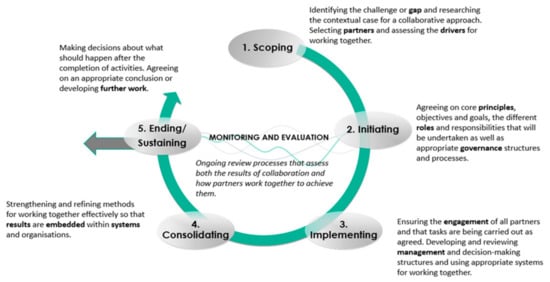

The different life cycle components highlighted [62,68,69,70,71,72] can be grouped into the five broad phases of partnership development outlined by Stott and Keatman (2005) [73] (see Figure 2). The authors stress that the phases they describe do not represent a rigorous linear progression as they may overlap or occur at different times. Nonetheless, they suggest that most partnership arrangements will work through a process cycle that begins with a scoping or preparatory phase in which the case for collaboration is made, the operational context examined, and partners selected. This is followed by a start-up or initiating phase in which the ground rules for collaboration are developed and governance systems put in place. The subsequent implementation phase involves ensuring accountability and engagement among partners so that tasks are carried out as agreed and the way is paved for a consolidation phase in which collaboration is strengthened and formalized. The fifth and final phase involves drawing the relationship to an appropriate conclusion or agreeing to further develop the initiative in new areas or activities. Throughout the cycle, review processes take place that monitor and evaluate both the impact of collaborative efforts and the health of working relationships among partners [73].

Figure 2.

Alianza Shire timeline. Adapted from Stott and Keatman (2005) [73].

2.3. A Framework for Our Partnership Lifecycle Analysis

This section provides an analytical framework for the subsequent study of the Alianza Shire case based on a literature review and focused on the formation period of a partnership (see Table 1). Frequently described as key to long-term success [74,75,76], during this time, the added value of collaboration and the goals and systems for different partners to work together are proposed [68,69]. Feldman et al. (2006) describe this period as an opportunity to “create a sense of community and an ability to transcend boundaries among participants” thereby fostering collaborative leadership [77,78]. However, because the process of working together is dynamic and develops over time, important aspects of partnership-building are often neglected at this stage [79]. This oversight can lead to challenges that have an impact on effective partnership performance going forward [65,80]. Table 1 summarizes the principal elements of the initial stages of partnership-building as highlighted in literature. The different sub-stages identified will be further used to analyze the case of Alianza Shire.

Table 1.

Multi-stakeholder partnerships formation stages.

3. Research Approach

3.1. Aims and Scope

This study responds to calls for further research into collaboration for the provision of access to unattended services and markets in refugee camps [3,5,6,20,57,59]. The aim of the paper is to explore the key ingredients that collaborative arrangements may encompass to provide holistic solutions in the delivery of basic services. To do this, we explore the early development of the Alianza Shire, a multi-stakeholder partnership that aims to supply access to energy services in refugee camps and their host communities [94]. The study further focuses on the facilitation role played by the Innovation and Technology Centre for Development at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (itdUPM). Although this facilitation role is a recognized function in partnership literature [81,94,95,96,97], it is not as common in the context of humanitarian collaborations [5,16]. We will, thus, consider the partnership facilitation role in this context and the particular convening potential that universities may assume in this regard.

In the ensuing sections, we will address the following research questions:

- What catalytic elements are needed for a transformational multi-stakeholder refugee response partnership to emerge?

- What degree of multi-stakeholder diversity is the most appropriate for providing basic services and/or creating market opportunities in refugee camps?

- What mechanisms can reinforce the transformational character of a multi-stakeholder refugee response partnership during the formation stage?

- Are there actors that are particularly suited to the role of facilitation in multi-stakeholder refugee response partnerships?

The contribution of our research is threefold:

- To assist understanding of “the factors that affect the effective development of multi-stakeholder partnerships with a humanitarian focus” [16], especially initial ingredients that maximize the transformational potential of a collaborative refugee response arrangement.

- To contribute to an understanding of “which situations require which type of partnership mechanisms to support the management of humanitarian logistics” [16], specifically in relation to partnerships that aim to provide basic services such as energy.

- To provide a practical example of how a university center can assume the facilitation role in a multi-stakeholder refugee response partnership by addressing both humanitarian and academic motivations for partnering [48].

3.2. Methodology

The article is based on an action-case methodology, a hybrid approach combining interpretation and intervention. Such an approach is indicated when “investigating a sufficiently rich context with a focused research question and a framework of ideas to be tested” [98]. A case study methodology provides empirical descriptions of a contemporary phenomenon, ‘the case’ [99], and may establish complex cause–effect relationships [100,101] that are adequate for theory building [102]. Partnerships and humanitarian logistics scholars have employed case studies extensively [72,103,104,105,106,107]. Action research, meanwhile, assist us to “gain knowledge through making deliberate interventions in order to achieve some desirable change in the organizational setting” [98]. It is also useful for theory building [108] and for testing a hypothesis through an intervention in an ‘organizational laboratory’ [109].

This inquiry is an opportunity to explore a relevant case [110] because of the shared purpose created among a diverse range of stakeholders and the novelty of this approach in the Spanish humanitarian context. In addition, it is an example of collaborative research [111,112] as a combination of external observers and researchers have worked together as agents of change engaged in creating “actionable scientific knowledge” [113]. In this case, two researchers provided insights and contrasts from their own experience in multi-stakeholder practice and the other four have been directly involved in facilitating the Alianza Shire. The information derived from this research has enabled production of practical-oriented knowledge pieces (see Appendix A) aimed at reinforcing the work of the Alianza Shire. Following this, and as the partnership became consolidated, efforts were made to systematize key learning from an academic point of view. This work included exploration of the transformational potential of the Alianza Shire and how relevant aspects could be shared with both academics and humanitarian practitioners [94].

The research presented here combined three data harvesting methods: (i) action research with the four researchers involved in the facilitation of the Alianza Shire; (ii) desk research involving an exhaustive analysis of Alianza Shire documentation (detailed in Appendix A), technical reports prepared for the Spanish Development Agency (AECID) on the viability of establishing a multi-stakeholder partnership in the humanitarian context; applications for grants awarded to the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) and funding reports; internal procedures, documents on lessons learned from the Alianza Shire, and external assessments of its work; and, (iii) semi-structured interviews with Steering Committee members (conducted in 2016) and a workshop with the Alianza Shire facilitation team (conducted in 2020).

The treatment of the qualitative data gathered by the three methods aforementioned has been developed using a collaborative content analysis [112] following the chronological categories detailed in Section 2.3 and refined through iterative work meetings among the authors of the study. Then, building upon the conceptualization of transformational partnership by Austin and Seitanidi (2012) [41,42], the elements and moments that may enhance the transformational potential in a multi-stakeholder refugee response partnership were identified.

4. Promoting Transformation during the Formation Stages of the Alianza Shire

This section describes the evolution of the Alianza Shire during the scoping, initiating, and pilot project stages presented in Section 2.3. In addition to comment on particular aspects of the formation phases, two overarching issues appear to have enhanced the partnership’s transformational prospects:

- The existence of feedback loops and learning spaces that enable partners to reflect on their work together [62,114,115,116,117].

- The critical role played by a facilitator or intermediary in steering and supporting the partnering process [7,74,81]. This function, which has been underexplored in humanitarian multi-stakeholder partnerships [5,16], includes the promotion of the abovementioned learning and reflection mechanisms [114], as well as people/relationship management and trust building [71].

4.1. Scoping

4.1.1. Making the Contextual Case for Collaboration

Austin and Seitanidi (2012:934) suggest that initial articulation of the problem to be addressed is central to assessing a ‘partnership fit potential’ and can be linked to the transformation that is derived from “synergistic value creation” [42]. They note, however, that deciding which partner holds the highest potential for the production of synergistic value can be time consuming and challenging [41].

In the Alianza Shire, there was no difficulty in deciding which partner had the greatest potential for producing synergistic value. We believe that this may be due to the fact that, unlike the partnerships between businesses and non-profit organizations that are the focus of Austin and Seitanidi’s work, the partnership was promoted by a public sector organization, the Spanish Development Agency (AECID). As well as its strong institutional reputation, the AECID also had a deep interest in learning from the process of collaboration. This focus contrasts with a prevailing interest among many actors in the humanitarian field in partnering with business to access financial resources [43,46,47]. These initiatives, as noted above, have tended to be short-term, ad hoc, and oriented towards emergency responses [46].

The AECID further sought to establish a multi-stakeholder partnership to tackle an unattended refugee response challenge with support from the Spanish private and academic sectors before identifying the concrete issue to be addressed. Such a focus was enhanced by the Agency’s explicit decision to engage itdUPM as coordinator and facilitator of the initiative. This owed much to itdUPM’s academic position and the perception that it was a neutral actor with strong legitimacy, a positive record of collaboration with the public and private sectors, and the ability to generate new knowledge.

Two scoping studies, commissioned in 2013 and 2014 by the AECID from itdUPM, explored the context of multi-stakeholder humanitarian collaborations and the potential for promoting a demonstration project to address energy access and service provision in refugee camps. In view of suggestions that initiatives in this area tended to focus on supply or demand, or a choice between supporting the development of innovation or diffusion and implementation of technologies [118], itdUPM sought to combine these strands in the provision of holistic service arrangements that involved key actors, including users, along the energy service value chain [21,22]. The rationale for this was based upon the fact that a structured supply chain for providing energy to refugee camps did not yet exist and humanitarian professionals lacked the technical capacity to address inefficiencies in the generation and transport of energy to refugee camps [57].

Selection of camps of operation was conducted by AECID based on different criteria as presence of the organization on the country, previous experience working on refugee camps in the country, and a favorable operational environment and security context. The AECID identified refugee camps fulfilling the previous criteria in the Shire region, northern Ethiopia, where the study of energy needs could provide the basis for developing pilot initiatives for the partnership. Shire camps have constituted a transit space country for Eritreans attempting to reach Europe. In recent years, thousands of Eritreans mostly minors (many of whom are unaccompanied), constantly fled from their country due to the continuous violations of human rights (see Appendix A). According to the UNHCR, at the beginning of Alianza Shire field operations (2017), there were around 36,000 refugees, mostly Eritreans minors (around 60%), in Shire refugee camps (see Appendix A).

4.1.2. Identifying and Selecting Potential Partners

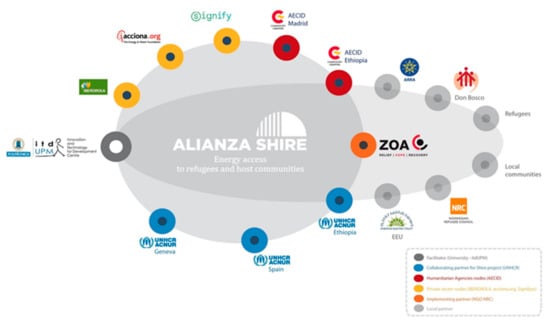

Austin and Seitanidi (2012) note that the “value creation potential” of a partnership will ultimately be determined by careful partner selection and assessment of the complementary nature of the different resources that each partner brings to the table [42]. In the case of the Alianza Shire, the complex tailored approach that was adopted for the partnership necessitated the involvement of a diverse range of actors to enable good coverage of all the services involved in energy supply. Rather than a single private sector partner, three businesses were chosen with expertise in different areas of service coverage. They included Iberdrola, a Spanish energy company with extensive experience of power generation and grid maintenance; Signify, a leader in lighting solutions; and the corporate foundation Acciona.org, which had successful experience of implementing innovative business models supplying energy to hard-to-reach households in Latin America. In addition to the AECID and itdUPM, these partners were also joined by UNHCR, which participated as a key stakeholder (See Appendix B: Alianza Shire’s stakeholders).

At the same time, careful attention was placed in choosing people with the capacity to embed the partnership and its work within their respective institutions [78]. To do this, itdUPM and the AECID drew upon previous connections that had been established between individuals and teams within the different organizations, particularly through previous projects and a Master’s program in Development Strategies and Technologies involving itdUPM [119]. These bonds were to provide the basis for strong and mutually supportive working relationships as the Alianza Shire developed its work.

4.1.3. Assessing Drivers, Barriers and Enablers

Although a detailed and explicit evaluation of drivers, barriers, and institutional enablers was not made at the level of each partner until Phase II (2018) [94], at the instigation of itdUPM, reflection on the reasons for working together ensured that partners explored ‘incentive alignment’ [83] and early clarity around partner motivations for collaborating. In addition to the positive reputations of potential partners and the first-class nature of the initiative, a key incentive for collaboration for all was that of engaging in an innovative process of learning and change [120]. Exploration of these drivers and incentives also offered the opportunity for partners to learn together, thus, beginning a reflection cycle that was to become an essential part of the partnership going forwards, and a core manifestation of its transformational intent.

4.2. Initiating

During the initiation phase, the Alianza Shire partners were able to build upon the transformational components that had been put in place during the scoping phase. These included the development of innovative partnering principles; a more refined set of objectives and goals; structures and systems for working together and a collaborative agreement.

4.2.1. Establishing Principles and Ground Rules for Collaboration

itdUPM positioned the need for agreement on a set of core principles for partners as a starting point for their work together. While many commentators stress the importance of “defining guiding principles, ground rules for working together [and] overall strategies for action” [69], the focus of these tends to be on internal tenets for working together such as equity, transparency, and mutual benefit among partners [76]. In the case of the Alianza Shire, however, the focus of partner principles was outward-looking, with emphasis on the achievement of an early tangible impact that would influence broader change processes. The principles that partners agreed upon included:

- Transformational mindset: the partnership was not a philanthropic initiative. Its aim was to promote broad change derived from practical action combining different partner capabilities. Potential for co-creation with private sector partners would rely on knowledge and skills rather than traditional resource contributions such as finance.

- Prototyping: an iterative logic that emphasized knowledge and learning would be promoted by a pilot project as the first joint initiative of the partnership.

- Grounded solutions: the first technical activities would focus on achieving solid impact through electrical grid improvement rather than other ‘attractive’ but risky solutions.

- No public communication before achievement of concrete results: until tangible results had been produced there would be no external communication on the work of the partnership.

While further study is warranted on how far the absence of internal principles affected partner relationships going forwards, the Alianza Shire case suggests that transformation can be enhanced by developing ‘rules of engagement’ that address external goals and desired impact, as well as internal relationships. The process of arriving at the principles also formed part of the ongoing reflection and learning cycle mentioned above, as partners jointly developed and debated the principles and agreed upon their focus.

4.2.2. Refining Objectives, Goal Setting and Confirming Resource Contributions

Arguing that precision around goals at this time can assist the ambition of the collaboration, Pattberg and Widerberg (2016) suggest that, alongside a common problem definition and “clear and measurable goals”, a “mapping of the compatibility between a partnership’s goals and other related processes (e.g., SDGs, CSR, human rights) reduces the risk of conflictive fragmentation” [74]. The suggestion that transformation can be enhanced by positioning clear goals in the context of a framework that integrates other relevant strands is demonstrated by the Alianza Shire’s development of a detailed workplan. This workplan, considered the operational context for activities, with information on the nature of the Shire refugee camps and evaluation of their energy needs; analysis of technical solutions for addressing the needs identified; conceptualization of a pilot project; and, in preparation for implementation, a detailed report on logistics and operational issues in the field. Particular attention was paid to presenting an integrated vision of how the partnership could best provide a basic service in a humanitarian context. This focus was to dovetail neatly with the aims of the 2030 Agenda, which was presented in 2015: promoting the targets of SDG7; working in a cross-cutting manner to produce co-benefits that would endorse other SDGs; and promoting partnerships for the goals (SDG17).

With regard to resources, a key differential element in the Alianza Shire was agreement by all partners that project activities would not be based on monetary exchange but on the creation of synergistic value derived from each partner’s core competencies. This decision meant that private sector partners were not obliged to make financial contributions to the partnership [94]. Instead, resource contributions included a grant provided by the AECID to itdUPM, and in-kind contributions such as human resources (staff and volunteers), provision of information, technical expertise, materials, experience, and knowledge.

4.2.3. Setting up Accountable Structures and Systems for Working Together

If the potential of partnerships to achieve positive change depends upon “appropriate mechanisms for their decision-making and accountability processes” that respond legitimately to stakeholder concerns [121,122], then careful deliberation is needed on appropriate governance forums and procedures for reaching decisions. A comprehensive managerial and governance structure was designed for the Alianza Shire that considered the different backgrounds, organizational cultures, and drivers of the five partner organizations and UNHCR, including a Steering Committee, a Technical Team, and a Communications Committee.

Once the governance mechanisms had been agreed upon, at the suggestion of itdUPM, the newly established Steering Committee invited two independent experts to carry out a ‘health check’ of the partnership. While initially developed to respond to specific considerations relating to humanitarian logistic complexities and the possible delays and uncertainties that might occur when putting infrastructure in the field in place, this early assessment exercise enabled partners to reflect upon necessary changes and reinforcement measures both within and outside the partnership before the implementation phase of its work. Recommendations from the assessment regarding the development of activities in the field were acted upon immediately, e.g., the appointment of the Norwegian Refugee Council as a local implementing partner. While recommendations for internal adjustments took time to put in place, partners were made aware that these two dimensions of partnering were interdependent, and that rapid external impact would be enhanced by greater attention to internal dynamics. The ‘health check’ findings provided an additional learning loop for partners, which enabled them to make eventual adjustments to their work. This suggests that external assessment of the partnership design process may offer an interesting model for other transformational collaborative initiatives.

4.2.4. Signing a Collaborative Agreement

All partners agreed that the Alianza Shire required an agreement to regulate its activities. However, the process of developing this was more complex than expected due to the lack of legal instruments for regulating this type of collaboration in the Spanish public sector and to rigid organizational protocols and internal processes that were not conducive to multi-actor collaboration, particularly in a humanitarian context. Reaching and signing a collaborative agreement, thus, took almost 18 months. In spite of this, the partners agreed to continue to work together. itdUPM made concerted efforts at this time to maintain links between the partners so that motivation to proceed with activities was thus high. The initial processes of reflection and learning together also appear to have assisted this process and contributed to the generation of “synergistic value” and the ambition to develop activities that would promote transformation.

4.3. Pilot Project and First Iteration

Implementing early pilot projects allows new practices to be tested and can assist in achieving meaningful results and the building of collaborative momentum [71,89,92,93]. In line with their focus on experimentation in order to obtain tangible results, and with funding from the AECID to carry out the implementation of a pilot project, partners in the Alianza Shire worked between January 2016 and May 2017 to improve energy access for 8000 refugees from the Adi Harush camp.

The pilot project sought to avoid a ‘welfare approach’ by focusing on respect for the dignity of the communities using the products and services developed by the partnership, and endorsing the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, independence, and universality. itdUPM also sought to position experimentation as central to this initiative by encouraging partners to test and systematize operational processes and ways of working together so that the internal visions and institutional cultures of the different partners were aligned.

In April 2016, with the pilot project underway, a further learning loop was created with the development of an ‘External Communications Plan’. The Plan laid the basis for sharing information about the Alianza Shire, reinforcing the importance of only communicating concrete results and ensuring that the visibility of each partner, and of the partnership as a whole, were compatible.

As well as covering technological and operational aspects, lessons from the pilot project also included organizational and partnership perspectives. This learning from practice was regarded as essential for scaling up the pilot project, sharing lessons with the international community regarding potential applicability in other contexts, and attracting the necessary resources for subsequent stages of the partnership’s work. Some of the lessons identified included the need for close study of the partnership’s operational context; attending to infrastructure maintenance with an on-site maintenance team of trained refugees and local technicians in order to guarantee durability; prioritization of livelihood strategies and income generating activities through activities such as mentoring, training, and creation of employment opportunities; and involvement and coordination of stakeholders and local partners through an energy coordination group for the Shire refugee camps. In addition to the importance of drawing upon both financial and in-kind resources such as knowledge, skills, human resources, capacities, and contacts, acknowledgement of the time required for building the partnership was noted.

Thanks to the pilot project, energy supply was positioned as a central element in the management of the Shire refugee camps and as a catalyst for new development possibilities. Thus, two key partners in the field joined the co-creation effort of the Alianza Shire: ARRA, the Ethiopian Agency for Refugee & Returnee Affairs, responsible for managing refugee camps in collaboration with UNHCR, and the Ethiopian Electric Utility, state-owned power company that is responsible for the electric grids that surround the Shire camps [94]. This was essential to design innovative strategies for the scaling up phase that delves into the integration of refugees in Ethiopia and to foster their relationships with the host communities (for example, creating mixed energy business among refugees and host community members) in coherence with the implementation of the CRRF in Ethiopia (see Appendix A).

In May 2017, findings from the pilot project were shared with a range of international stakeholders (Including UNHCR, the European Union, and energy access networks and initiatives such as the Moving Energy Initiative and Safe Access to Fuel and Energy). As a result, as well as an assessment of the relevance of the Alianza Shire’s work, the design of next steps and the consolidation of relationships, funding was obtained from the European Union’s Emergency Trust Fund to scale up the pilot project to four refugee camps and reach more than 40,000 people between 2018 and 2021.

5. Discussion

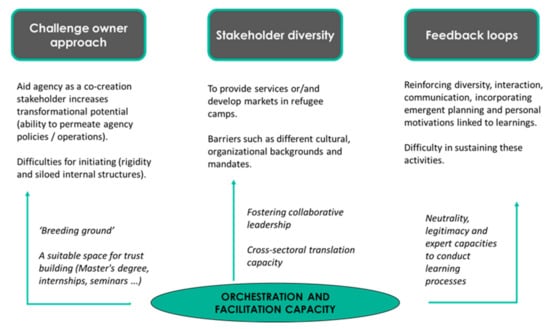

Three major implications are derived from our case study: (i) a series of design elements can enhance the transformational potential of multi-stakeholder partnership in the context of refugee response; (ii) the facilitation role is crucial in catalyzing this potential, and (iii) interdisciplinary centers at universities possess differential characteristics, which make them especially suitable for facilitating humanitarian partnerships. These issues are discussed below in response to the research questions posed in Section 3.1.

What catalytic elements are needed for a transformational multi-stakeholder refugee response partnership to emerge?

As noted above, partnership formation usually starts with the identification of a challenge by either a profit or non-profit organization [41,42,62]. However, in the case of the Alianza Shire, the ‘push’ was provided by the Spanish Aid Agency (AECID), which instead of its standard modus operandi of financing a specific project, sought to learn from multi-stakeholder partnership practice. This kind of demand-led approach [123,124], which involves a public policy owner in a co-creation process aligns neatly with some of the new trends in SDG implementation based on multi-stakeholder collaboration [125,126]. In this regard, it is worth noting that the impact of such arrangements may extend beyond the partnership itself as some of the transformational ingredients may permeate aid agency operations by, for example, supporting refugee assistance through knowledge transfer, education and capacity building, service supply, and market access [5,6,20,127]. In addition, flagship partnerships such as the Alianza Shire may encourage more advanced multi-stakeholder policies in aid agencies and assist in breaking down silos among them [3].

Public institutions have been singularly determined by specialized and fragmented structures in the last few decades [128,129,130]. As a result, aid agencies have developed strong cultural barriers that hinder knowledge-based and collaborative approaches [131,132]. Solid facilitation and orchestration vehicles may, thus, be particularly necessary for sustaining multi-stakeholder refugee response partnerships. These vehicles may also take advantage of combined top-down and bottom-up approaches so that a shared vision is created that is based on knowledge and trust [7].

What degree of multi-stakeholder diversity is the most appropriate for providing basic services and/or creating market opportunities in refugee camps?

Because the Alianza Shire opted for a comprehensive approach that conceived energy delivery as a service, stakeholder selection was necessarily broad. In addition to a combination of organizations with which the facilitator had prior association relationships, other organizations were chosen in order to ensure an appropriate “mix” of both technical and institutional capacities. The stakeholders included: three multinational companies that contributed complementary skills such as energy generation, grid maintenance, lightning and business models; refugee camp stakeholders who could become energy-based entrepreneurs and ensure a user-led energy distribution system; an international NGO able to support local operational capacities; UNHCR as a coordinator in the refugee camps, and the AECID, which provided an institutional framework and specialized knowledge in refugee protection.

Such diverse and extended partnerships are likely to foster trends that assist the “de-materialization of refugee aid” [5]. However, they also face substantial barriers in their work to develop effective multi-stakeholder collaboration. Appropriate national and international regulations are both scarce or inexistent, and processes such as the signing of collaborative agreements may pose unacceptable delays, which put the stability of a partnership at risk. The diversity of organizations with different cultural, organizational backgrounds and mandates also requires a stable and strong cross-sector translating role that needs to be developed by the partnership facilitator [95,115,133].

What mechanisms can reinforce the transformational character of a multi-stakeholder refugee response partnership during the formation stage?

Feedback loops and continuous learning have been advocated as powerful tools for building collaborative momentum [71]. As well as assisting the alignment of different stakeholder visions [115,116], they have also been highlighted as intrinsic motivators for partnering work [120] (Stott and Murphy, 2020). Although humanitarian actors possess limited organizational learning capacities [117], knowledge transfer is also regarded as central to new multi-stakeholder partnerships for refugee response that are focused on service provision and market integration [5,6].

There is little evidence of learning consolidation mechanisms in humanitarian multi-stakeholder practice. The Alianza Shire shows how a series of feedback loops implemented during its formation period were central to reinforcing its transformational character. Among these, four specific opportunities for reflection have been identified:

- At the end of the scoping stage, the exploratory studies conducted by itdUPM offered the opportunity to ensure the diversity and complementarity of partners.

- In the initiation stage, agreement on partnership principles reinforced the transformational vision of the collaboration and distinguished it from more traditional or philanthropic collaborations.

- Before the pilot project, the external health-check enabled the improvement of operational issues and enhanced partnership dynamics, and the communications plan assured a dissemination approach focused only on the results, thus, avoiding a welfare approach to its work.

- After the pilot project, the development of a case study helped to consolidate lessons learned and to share them with key stakeholders. This was essential to ensuring the scale-up of the Alianza Shire’s activities and to integrate local stakeholders (ARRA and EEU) via specific initiatives much aligned with their internal priorities and policies.

These feedback loops are revealed as a powerful tool for the consolidation of learning, an opportunity to include emergent planning within the partnership, and a way of highlighting the interrelationship between the external impact and internal dynamics of a partnership. In this regard, it is important to highlight the role of the facilitator in promoting reflection and, thus, enabling the development of relationships of trust. In the case of the Alianza Shire, itdUPM’s emphasis on the need for reflection spaces and feedback loops has been an important factor in positioning the need for transformation from the start and ensuring buy-in for this from all the partners involved.

Are there actors that are particularly suited to the role of facilitation in multi-stakeholder refugee response partnerships?

Throughout the article, we have emphasized the importance of the facilitation role in effective multi-stakeholder collaboration in the humanitarian context. This role is critical for addressing the fragmented and silo-based structures of public aid agencies [131,132]; the multiplicity and interplay of different organizational languages in complex refugee response partnerships [5,6], and limitations to organizational learning [117].

In the Alianza Shire, an inter-disciplinary sustainability center within a university has played the facilitation role. We believe that this kind of academic vehicle [134] has particular characteristics [135] that make it especially suitable for undertaking the facilitation of refugee response partnerships, and these include:

- Flexibility and the capacity to develop a propitious ‘incubating environment’ and trust building processes using a combination of public seminars, exploratory studies, and internships.

- The possibility of creating practitioner-academic teams that can cultivate distributed leadership and strong cross-sectoral capacity.

- Neutrality, legitimacy, and expert capacities that support learning processes.

In addition to providing facilitation skills, the active involvement in a refugee response partnership of a sustainability-focused center in a university may offer an ideal platform for connecting university research with difficult SDG challenges in a practical way. In the case of the Alianza Shire, the trust built by itdUPM among key stakeholders in the field provided privileged access to the Shire refugee camps for several UPM research groups. This further enabled the development of an innovative mixed-method needs assessment tool that permitted Shire camp coordinators to improve their energy, shelter, and food security operations in an interdisciplinary and integrated manner [136]. These findings indicate that although the facilitation role was conducted by one organization at the start of the partnership, this role was progressively assumed by the other partners over time.

6. Conclusions

This article has analyzed dynamics among key actors in the creation and development of a multi-stakeholder partnership aimed at providing energy access to refugee camps in a holistic way. The Alianza Shire case study demonstrates that the active participation of aid agencies in the co-creation process of a multi-stakeholder partnership may increase the transformational potential of refugee response. The study also indicates that reliable access to basic services in refugee camps requires interaction among a wide set of partners with different and complementary capacities and assets. Finally, feedback loops and the consolidation of internal learning have emerged as essential practices for the effective management of complex multi-stakeholder refugee response partnerships. These processes reinforce partner interaction and communication, enhance personal incentives for involvement, and enable the integration of emergent planning.

The Alianza Shire case study also reveals the important difficulties and challenges that complex multi-stakeholder refugee response partnerships may face. These obstacles include rigidity and siloed internal structures in public and private organizations, and barriers that relate to different cultural, organizational backgrounds and mandates. The critical role played by a partnership facilitator in addressing these issues has been highlighted by the work of itdUPM, a sustainability-oriented center in a university. By generating ‘safe spaces’ that foster trust-building, providing a cross-sector ‘translation’ service, and affording the legitimacy and expert knowledge required to conduct learning processes, centers of this kind appear to possess a particular capacity for nurturing the transformational potential of multi-stakeholder refugee response partnerships (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Alianza Shire key transformational elements.

As situations of displacement are increasing, the importance of trends that advocate for services delivery and market integration in refugee response are likely to grow in importance [3,5,6,57,59]. We believe that different sector actors (public, private, civil society, and academia) need to play active roles in this context, and that detailed studies of ongoing multi-stakeholder partnerships may help researchers and practitioners to effectively contribute to new response policies such as the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework. In our opinion, further research should be devoted to i) exploring the possibility of a stronger role for public agencies in collaborative responses; ii) studying integrative mechanisms that balance the diverse and extended participation of different and complementary stakeholders and the managerial and shared vision creation complexity that these approaches entail; and iii) expanding learning exchange among facilitating actors in multi-stakeholder refugee response partnerships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.-S.; methodology, J.M.-S., T.S.-C. and L.S.; validation, T.S.-C., L.S. and R.C.-G.; formal analysis, J.M.-S.; investigation, J.M.-S., T.S.-C., J.M., L.S. and R.C.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.-S., T.S.-C., L.S., J.M. and R.C.-G.; writing—review and editing, J.M.-S., L.S., J.M. and C.M.; visualization, J.M.-S.; supervision, T.S.-C., J.M., R.C.-G. and C.M.; project administration, J.M.; funding acquisition, C.M. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The doctoral research of which this article is part has been supported by funding from Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) and Iberdrola-UPM Chair on Sustainable Development Goals. The Alianza Shire Phase II Project is funded by the European Union and the Spanish Cooperation (AECID); and cofounded by in-kind contribution of UPM, Iberdrola, Signify and Acciona.org Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://nube.cesvima.upm.es/index.php/s/1kibPPyM0vmgKma (accessed on 12 October 2021).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of the representatives of the different organizations involved in the Alianza Shire (Steering, Management and Communications Committees, and Project Office), and members of the refugee community and practitioners working in the Alianza Shire’s activities in the field. The authors are also grateful to the following for their contributions to the work of the Alianza Shire and to this research: Alejandra Rojo (former Alianza Shire Coordinator), Manuel Pastor (former Operations Officer), Ander Arzamendi (former Operations Officer), Xose Ramil (Communications Officer) and Dalia Mendoza (former Innovation Assistant).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Evidence Used for Case-Study Analysis

Documentation accessible at: https://nube.cesvima.upm.es/index.php/s/1kibPPyM0vmgKma (accessed on 12 October 2021).

Table A1.

Evidence list.

Table A1.

Evidence list.

| Evidence | Date | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-stakeholder Partnerships in Humanitarian Action | Dec 2012 | Bases (benefits and risks, stages, etc.) multi-stakeholder partnerships in humanitarian action (including case studies). |

| Presentation at ECOSOC (Geneve) | July 2013 | Conclusions on the maturity of partnerships and good practices. |

| Master’s Thesis of itdUPM student | Oct 2013 | Goes deeper into the previous document. |

| UNHCR Ethiopia factsheet | Feb 2017 | Description of refugee situation in Ethiopia. |

| Amnesty International Annual Report 2016/2017 | Feb 2017 | Description of the Eritrea human rights situation. |

| Shire energy analysis | Dec 2013 | Pre-identification of energy needs in Shire. Recommendation of the choice of the camps by UNHCR. |

| Expressions of interest for companies | Dec 2013 | Pre-identification of potential partners for the Alianza Shire. |

| Summary of products to AECID | Dec 2013 | Summary of the work commissioned by SHO for the preparatory stage. |

| Startup grant | Dec 2013 | AECID grant to the UPM to form the Alianza Shire. |

| Grant’s justification | Sep 2015 | Term: Feb 2014–July 2015 Deliverables: Alianza Shire’s creation agreement and working, coordination, and communication mechanisms. Shire refugee camps characterization report and energy needs assessment. Synthesis and characterization report of technical solutions for Shire refugee camps. Pilot Project Design: Concept note. Preparation for implementation: Report on logistics and operational issues in the field. |

| Initial MoU of Alianza Shire | Oct 2015 | Formal agreement. Delay due to lack of instruments. |

| MoU UPM-UNHCR | Nov 2014 | UNHCR is not part of the MoU but signs an agreement with UPM. |

| Product first grant | Jul 2014 | Characterization of Shire Refugee Camps and Energy Needs Assessment. |

| Product first grant | Feb 2015 | Characterization of technical solutions. |

| Product first grant | March 2015 | Optimal model for electricity distribution grid in refugee camps: Audit of Shire Camps. |

| Product first grant | Ap 2015 | Optimal model for electricity distribution grid on refugee camps: guide for optimal management. |

| Product first grant | Sep 2015 | Report on logistics and field operation keys. |

| Report lessons learned | Oct 2015 | Elaborated by Leda Stott and Maria Prandi (independent experts). |

| Grant to implement pilot | Nov 15 | Grant award for implementation. |

| Orientations and principles | Feb 2016 | Keys to immediate improvements and the basis for the partnership to operate in the future. |

| External communication plan | Ap 2016 | Basis for communication of the partnership. |

| Pilot project technical report | March 2017 | Implementation technical report. |

| Case study | May 2017 | Systematization lessons learned Phase I. |

| Presentation of results | May 2017 | Newspaper notice. |

| Analysis of Alianza Shire transformational potential | Jan 2020 | Research article. |

| CRRF in Ethiopia | 2018 | Briefing note issued by UNHCR about the implementation strategy of CRRF in Ethiopia. |

Appendix B. Alianza Shire’s Stakeholders

Figure A1.

Alianza Shire key stakeholder representation.

References

- United Nations. New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants; Resolution 71/1 Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 3 October 2016; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, R. The Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework: A Commentary. J. Refug. Stud. 2018, 31, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. Turning the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework into Reality. Forced Migr. Rev. 2017, 56, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Türk, V.; Garlick, M. From Burdens and Responsibilities to Opportunities: The Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework and a Global Compact on Refugees. Int. J. Refug. Law 2016, 28, 656–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, E. More Logistics, Less Aid: Humanitarian-Business Partnerships and Sustainability in the Refugee Camp. World Dev. 2021, 142, 105424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasini, R.M. The Evolutions of Humanitarian-Private Partnerships: Collaborative Frameworks Under Review. In The Palgrave Handbook of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management; Springer: London, UK, 2018; pp. 627–635. [Google Scholar]

- Horan, D. A New Approach to Partnerships for SDG Transformations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bealt, J.; Barrera, J.C.F.; Mansouri, S.A. Collaborative Relationships between Logistics Service Providers and Humanitarian Organizations during Disaster Relief Operations. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain. Manag. 2016, 6, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Lindgreen, A.; Vanhamme, J. Developing Supply Chains in Disaster Relief Operations through Cross-sector Socially Oriented Collaborations: A Theoretical Model. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2009, 14, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlin, R.; Larson, P.D. Building Humanitarian Supply Chain Relationships: Lessons from Leading Practitioners. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain. Manag. 2011, 1, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Fritz, L. Disaster Relief, Inc. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 114–122, 158. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wassenhove, L.N. Humanitarian Aid Logistics: Supply Chain Management in High Gear. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2006, 57, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Luthra, S.; Venkatesh, V.G.; Yadav, G. Towards Understanding Key Enablers to Green Humanitarian Supply Chain Management Practices. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2020, 31, 1111–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, R.; Heaslip, G.; McMullan, C. Coordination to Choreography: The Evolution of Humanitarian Supply Chains. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain. Manag. 2020, 10, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmala, N.; De Leeuw, S.; Dullaert, W. Humanitarian-Business Partnerships in Managing Humanitarian Logistics. Supply Chain. Manag. 2017, 22, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, S.R.; Haavisto, I. Collaboration in Humanitarian Supply Chains: An Organisational Culture Framework. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 5611–5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.T.; Kolluru, R.; Smith, M. Leveraging Public-private Partnerships to Improve Community Resilience in Times of Disaster. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasini, R.M.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. From Preparedness to Partnerships: Case Study Research on Humanitarian Logistics. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2009, 16, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husban, M.; Adams, C. Sustainable Refugee Migration: A Rethink towards a Positive Capability Approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg-Jansen, S.; Tunge, T.; Kayumba, T. Inclusive Energy Solutions in Refugee Camps. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 990–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boodhna, A.; Sissons, C.; Fullwood-Thomas, J. A Systems Thinking Approach for Energy Markets in Fragile Places. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 997–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, J.; Rothkop, J.; Miller, G. Off-Grid Solar PV Power for Humanitarian Action: From Emergency Communications to Refugee Camp Micro-Grids. Procedia Eng. 2014, 78, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, K. Adopting a Market-Based Approach to Boost Energy Access in Displaced Contexts; The Moving Energy Initiative: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, T.; Nahian, A.J.; Ma, H. A Hybrid Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Approach to Solve Renewable Energy Technology Selection Problem for Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aste, N.; Barbieri, J.; Berizzi, A.; Colombo, E.; del Pero, C.; Leonforte, F.; Merlo, M.; Riva, F. Innovative Energy Solutions for Improving Food Preservation in Humanitarian Contexts: A Case Study from Informal Refugees Settlements in Lebanon. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2017, 22, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafham, O.; Lahn, G.; Lehne, J. Energy Solutions with Both Humanitarian and Development Pay-Offs. Forced Migr. Rev. 2016, 52, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ten-Palomares, M.; Motard, E. Challenging Traditional Energy Settings in the Humanitarian Aid: Experiences from Doctors Without Borders. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2020, 33, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.J.M.; Sandwell, P.; Williamson, S.J.; Harper, P.W. A PESTLE Analysis of Solar Home Systems in Refugee Camps in Rwanda. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikar, C.; Gronalt, M.; Hirsch, P. A Decision Support System for Coordinated Disaster Relief Distribution. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 57, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoldrick, C. The Future of Humanitarian Action: An ICRC Perspective. Int. Rev. Red Cross 2011, 93, 965–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, R.G.; Kovács, G.; Spens, K. Identifying Challenges in Humanitarian Logistics. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 506–528. [Google Scholar]

- Tatham, P.; Pettit, S.; Scholten, K.; Scott, P.S.; Fynes, B. (Le) Agility in Humanitarian Aid (NGO) Supply Chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 623–635. [Google Scholar]

- Oloruntoba, R.; Gray, R. Customer Service in Emergency Relief Chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcik, B.; Beamon, B.M.; Krejci, C.C.; Muramatsu, K.M.; Ramirez, M. Coordination in Humanitarian Relief Chains: Practices, Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 126, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueede, D.; Kreutzer, K. Legitimation Work within a Cross-Sector Social Partnership. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamon, B.M.; Balcik, B. Performance Measurement in Humanitarian Relief Chains. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2008, 21, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, A.; Rossi, S.; Conforti, A. Agile and Lean Principles in the Humanitarian Supply Chain. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain. Manag. 2012, 2, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatham, P.; Pettit, S.; Charles, A.; Lauras, M.; Van Wassenhove, L. A Model to Define and Assess the Agility of Supply Chains: Building on Humanitarian Experience. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 722–741. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative Value Creation: A Review of Partnering between Nonprofits and Businesses: Part I. Value Creation Spectrum and Collaboration Stages. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 726–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative Value Creation: A Review of Partnering between Nonprofits and Businesses. Part 2: Partnership Processes and Outcomes. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 929–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, D.; Sharma, A. Resilience: Saving Lives Today, Investing for Tomorrow. In World Disasters Report; IFRC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A. Leveraging Private Expertise for Humanitarian Supply Chains. Forced Migr. Rev. 2004, 21, 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gatignon, A.; Van Wassenhove, L. When the Music Changes, so Does the Dance: The TNT/WFP Partnership,‘Moving the World’Five Years On. INSEAD–ecch Case 2009, 2, 2010–5596. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield, M. Post-Humanitarianism: Governing Precarity in the Digital World; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Smith, T. Humanitarian Neophilia: The ‘Innovation Turn’and Its Implications. Third World Q. 2016, 37, 2229–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, L.; Kalubi, D.; Schönenberger, K. Opinion: Academic-Humanitarian Technology Partnerships: An Unhappy Marriage? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2102713118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Lee, K.E.; Mokhtar, M. Streamlining Non-governmental Organizations’ Programs towards Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: A Conceptual Framework. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilhorst, T.; De Milliano, C.; Strauch, L. Learning from and about Partners for Resilience: A Qualitative Study-Synthesis Report; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, C.; Moser, S.C.; Kasperson, R.E.; Dabelko, G.D. Linking Vulnerability, Adaptation and Resilience Science to Practice: Pathways, Players and Partnerships. Integr. Sci. Policy. 2012, 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution 70/1 Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 25 September 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lemberg-Pedersen, M.; Haioty, E. Re-Assembling the Surveillable Refugee Body in the Era of Data-Craving. Citizsh. Stud. 2020, 24, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenner, K.; Turner, L. Making Refugees Work? The Politics of Integrating Syrian Refugees into the Labor Market in Jordan. Middle East Crit. 2019, 28, 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, L. ‘# Refugees Can Be Entrepreneurs Too!’Humanitarianism, Race, and the Marketing of Syrian Refugees. Rev. Int. Stud. 2020, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ziadah, R. Circulating Power: Humanitarian Logistics, Militarism, and the United Arab Emirates. Antipode 2019, 51, 1684–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanca, R. Sustainable Energy Provision among Displaced Populations: Policy and Practice; Chatham House, The Royal Institute of International Affairs: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Summary of the First Global Refugee Forum by the Co-Convenors. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/events/conferences/5dfa70e24/summary-first-global-refugee-forum-co-convenors.html (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- The Power to Respond. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41560-019-0528-6 (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Huber, S.; Mach, E. Policies for Increased Sustainable Energy Access in Displacement Settings. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 1000–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M.; Baumann, H.; Ruggles, R.; Sadtler, T.M. Disruptive Innovation for Social Change. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 163, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Selsky, J.W.; Parker, B. Cross-Sector Partnerships to Address Social Issues: Challenges to Theory and Practice. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laamanen, M.; Skålén, P. Collective–Conflictual Value Co-Creation: A Strategic Action Field Approach. Mark. Theory 2015, 15, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, J.M. Assessing and Improving Partnership Relationships and Outcomes: A Proposed Framework. Eval. Program. Plan. 2002, 25, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, K.; Gomme, J.; Mugabi, J.; Stott, L. Assessing Partnership Performance: Understanding the Drivers for Success; Building Partnerships for Development (BPDWS): London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wigboldus, S.; Brouwers, J.; Snel, H. How a Strategic Scoping Canvas Can Facilitate Collaboration between Partners in Sustainability Transitions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggins, D.; Trollsund, F.; Høiby, A. Applying a Life Cycle Approach to Project Management Methods. In Proceedings of the EURAM 2016: European Academy of Management Conference, Paris, France, 1–4 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. The Design and Implementation of Cross-Sector Collaborations: Propositions from the Literature. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Briggs, X. Perfect Fit or Shotgun Marriage? Understanding the Power and Pitfalls in Partnerships; The Art and Science of Community Problem Solving project at Harvard University: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ellram, L.M.; Edis, O.R. A Case Study of Successful Partnering Implementation. Int. J. Purch. Mater. Manag. 1996, 32, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, S.E.; Magnan, G.M.; McCarter, M.W. A Three-stage Implementation Model for Supply Chain Collaboration. J. Bus. Logist. 2008, 29, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letaifa, S.B. The Uneasy Transition from Supply Chains to Ecosystems. Manag. Decis. 2014, 52, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L.; Keatman, T. Tools for Exploring Community Engagement in Partnerships. In Practitioner Note; Building Partnerships for Development in Water and Sanitation (BPD): London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pattberg, P.; Widerberg, O. Transnational Multistakeholder Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Conditions for Success. Ambio 2016, 45, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L. Partnership and Social Progress: Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration in Context. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tennyson, R. The Partnering Tool Book; International Business Leaders Forum: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M.S.; Khademian, A.M.; Ingram, H.; Schneider, A.S. Ways of Knowing and Inclusive Management Practices. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxham, C.; Vangen, S. Leadership in the Shaping and Implementation of Collaboration Agendas: How Things Happen in a (Not Quite) Joined-up World. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 1159–1175. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, M.; Vonderembse, M.A.; Zhang, Q.; Ragu-Nathan, T. Supply Chain Collaboration: Conceptualisation and Instrument Development. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2010, 48, 6613–6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L.; Scoppetta, A. Adding Value: The Broker Role in Partnerships for Employment and Social Inclusion in Europe. Betwixt Between J. Partnersh. Brok. 2013, 1, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tennyson, R. The Brokering Guidebook. Navigating Effective Sustainable Development Partnerships; IBLF: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Seitanidi, M.M.; Crane, A. Implementing CSR through Partnerships: Understanding the Selection, Design and Institutionalisation of Nonprofit-Business Partnerships. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simatupang, T.M.; Sridharan, R. An Integrative Framework for Supply Chain Collaboration. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2005, 16, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuten, T.L.; Urban, D.J. An Expanded Model of Business-to-Business Partnership Formation and Success. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2001, 30, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, B.C.; Bryson, J.M. Integrative Leadership and the Creation and Maintenance of Cross-Sector Collaborations. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, V.; Skelcher, C. The Dynamics of Multi-organizational Partnerships: An Analysis of Changing Modes of Governance. Public Adm. 1998, 76, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D.M.; Emmelhainz, M.A.; Gardner, J.T. Developing and Implementing Supply Chain Partnerships. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 1996, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasbergen, P. Understanding Partnerships for Sustainable Development Analytically. Ladder Partnersh. Act. A Methodol. Tool Environ. Policy Gov. 2011, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, P.S.; Van de Ven, A.H. Developmental Processes of Cooperative Interorganizational Relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]