1. Introduction

Urban planning has profoundly evolved with respect to the objectives, methods, and tools that had promoted and spread it to govern the phenomena of pollution, congestion, and settlement spread caused by the industrial revolution that developed in England in the late eighteenth century and subsequently spread throughout the world [

1,

2,

3].

Contemporary urban planning has changed objectives, actors, methods, and tools following the progressive affirmation of some environmental, economic, and social phenomena and as a consequence of planning failures: the demographic contraction and the progressive aging of many cities and nations of the so-called industrialized world [

4,

5,

6], the affirmation of the cultural paradigm of sustainable development still to be implemented in ordinary practices [

7,

8,

9] to modify the era of the Anthropocene and to reconstruct a balanced compatible relationship between man and nature [

10,

11], the shift of meaning of contemporary urban planning from the expansion to the re-generation of the consolidated city, through the concepts of recovery, redevelopment and finally regeneration [

12,

13,

14], with attention to the reuse, reversibility, and temporariness of the interventions [

15,

16,

17]. In this cultural context, tactical urbanism and more generally the multiple forms of reuse of the existing city and the temporary uses that are characterizing it can play a role which overcomes the external one of a response to random circumstances but can be planned as a method to face the multiple forms and evolutions of the contemporary city. Furthermore, and more so following the constraints imposed by an epochal event such as the COVID-19 pandemic, tactical and temporary urban experiments are becoming more and more a diffused technique to face urban problems concerning, at the same time, public space as such and streets understood as mobility infrastructures, given the urge of health-safe and sustainable adaptations in daily urban transportation. Expanding to these new domains, tactical approaches are showing new emergent values that are mostly far from having been completely systematized and assessed [

18] and whose interest mostly relies in the tension between their ephemerality and their need to be radical, feasible, challenge driven, strategic, and mobilizing [

18].

After a brief description of the state of the art of the urban design of public space in Italy, the work focuses on three case studies from different cities in Italy, chosen for both their differences and analogies, that we consider useful to allow the construction of more general conclusions that might be advantageous for different contexts at a global scale.

The common ground of these cases—apart from being in Italy of course—is the use they make of tactical urbanism approaches. Tactical urbanism was born as an independent, bottom-up approach, promoting the public and collective use of the city to avoid the usual cumbersome administrative bureaucracy, sometimes carrying strong critical positions to the institutional action on the urban dimension, but also to support local communities to develop immediate solutions to the increasingly difficult economic conditions determined by the global financial crisis. These three cities, each in its own way, are showing the intention to learn from these bottom-up approach and taking their advantages into the institutional toolbox. From these experiences, mostly realized under the pressure of the pandemic, possible innovative solutions for the institutional action towards public space seem to emerge. This research is aimed at understanding the results and potential of such a methodology of temporary and reversible solutions according to the “build-measure-learn” sequence [

19,

20].

2. Urban and Public Space Design in Italy: A Contested Research Field

The first steps of what we know as Urban Design were taken between the late 1950s and the 1960s, and the researchers’ community widely agrees on considering 1956’s Conference on Urban Design at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, promoted by José Luis Sert, the founding act of the discipline. While the progressive consolidation and growth of Urban Design through the Anglo-Saxon scientific tradition may be understood as an obviously multifaceted but continuous process, the Italian debate around this field, instead, followed a definitely less coherent path in the following years. The 1960s appeared as a very fertile decade, with crucial contributions to the field coming by the most important exponents of the Italian academic and cultural debate. To only mention some of those: Ernesto Nathan Rogers was the Italian referent of CIAM and had a direct link with Sert’s seminal activity, which he injected in the academic milieu of Milan’s Polytechnic University; Giuseppe Samonà introduced urban planning and design—still not clearly differentiated—in the Italian academic world, with a pulsing center in Venice; Ludovico Quaroni’s professional and academic activity, with its heart in Rome’s Architecture Faculty, had explicit roots within the emerging coeval American and English literature on urban design. Yet, such a class of pioneer intellectuals of progetto urbano [

21] were immerse in a dense, magmatic discourse in which the role of architects and planners was far from openly discerned, and rather based its complexity and distinguished value on this accepted ambiguity [

22]. This allowed, at the same time, both the brighter and darker sides of a demiurgic and authorial approach to urban design, in a time of quick demographic and urban expansion of the country.

And probably such a drastic and enduring growth in the whole real estate sector, with its urge for a quicker dialogue between the technical and the political class, ended up gradually accelerating a split between urban planning and the architectural discourse, leading to their divorce throughout the 1980s. So, as the first entrenched in the very large scale of decision, progressively losing touch with the human dimension of everyday life, the second sheltered mainly around the design of buildings, with low interest in the relational space hosting the social fabric in between them. In this bifurcation and progressive atomization of knowledge fields, thus, public space remained finally uncovered, ultimately orphan, expelled by the main research fields in Italy. Not that the progetto urbano ended existing in the academic field or in the laical cultural debate, naturally: on the contrary, its weight rather consolidated around the important tradition of Muratori’s studies around the relationship between building typologies and the urban form and, again, on masterplanning as the preferential method for designing whole city parts.

Another aspect that surely characterizes the Italian cultural context around urban studies is surely the importance of history, conservation, and heritage. The second postwar period was in fact dominated by the debate about post-CIAM approach at the recovery of ancient urban centers, crossbreeding with the very rich existing tradition of restoration. This made the scene less permeable towards new approaches coming particularly by debates typically shaped around the American city and its specific topics. Interestingly enough, despite the European traditional city having had an implicitly stratified culture of public space [

23], the idea of a need of a specialized discipline dedicated to its design would finally come from the opposite side: the U.S., where the gigantism of brand new transport infrastructures, industrial areas or shopping centers acted as unavoidable detectors of a hidden knowledge gap, as found in Jacobs’ [

24] and Ventury and Scott Brown’s [

25] masterpieces.

So, it was not before the advanced 1990s that a public-space-oriented design research appeared as an urge in the Italian debate. As Gregotti and Secchi wrote in a double issue of Casabella n. 597/598 dedicated to the topic: “In our opinion the new problem is on the one hand to identify the subtle difference between open space and public space, and on the other to find a new meaning and function for the residual spaces which contemporary life has somehow discarded; then, one should also determine whether architectural design is capable of controlling the significance of new functional themes, or to combine the single concentration of different functions […]. First of all, the problem of the large scale, which leaves little spaces open to any form of layering of participation, allowing only an artificial kind of use which is practically always demagogical. Then, we have the problem of infinite functional flexibility, or better of its mechanical translation, which presents itself as a serious obstacle to all forms of articulation. […] Finally, we have the problem of cultural inhomogeneity within the discipline and beyond, to be found in homogeneous social will based on a conception of individual freedom which resembles the idea of disobedience against collective interest”

“The plans produced by planners, dominated by movement and speed, forgot or took for granted all that referred to the idea of settlement and of “belonging”: here, open space becomes infrastructures or services, or, more elusively, “green”, or standard, area of respect, building limit or generic container in densities or coefficients can be placed as determined by social interaction, with a complex system of contractual exchanges between many social actors. […] In the postwar period, mostly in Italy and in the Mediterranean countries, rather than in Northern Europe, open spaces have become an horizontal expanse; the paradox being that this vastness is made of residues. Forgotten by designers’ thought and pencils, by public developers and private speculators, by administrators and citizens alike, it has often become a place of marginal social practice”

And if this gap finally started to be filled in during the 2000s, it is to be observed how urban design as a discipline still struggles to find its place in both academy and the professional field. For its elusive, inherently anti-iconic nature, public space is still often treated as an attribute of architecture, with ancillary roles towards the buildings. Its attributed relevance suffers from the same cultural bias affecting interior design and both, in a somewhat machist perspective, are commonly downgraded to a lower level of interest, as if their inherent anti-volumetric [

28] and subtler approach implied a lesser complexity. And lastly, as public space design also deals with greening, it is not rarely segregated outside the architecture spectrum together with landscape design, despite the efforts of magazines and a growing cultural movement to overcome this preconception.

Finally, the outburst of tactical urbanism, to which this paper is dedicated, starting in 2010s from American grassroots and diffused globally through a quick web-based word of mouth, landed in Italy on such a cultural minefield, and it is no surprise that it found a skeptical audience, to say the least. In many professionals and academics environments, these temporary and low-budget interventions have often been tagged as either belittling the glorious tradition and the original ambitions of Italian culture of progetto urbano, stealing the millenary role of architecture in the evolution of cities or, when used inside institutionally led programs, even a bait-and-switch to build easy political consensus without realizing real systemic changes [

29] bypassing the technical class of designers. Furtherly, the typical frugality of these ad interim solutions, mainly made of ground painting and simple, stand-alone furniture elements and potted plants, is sometimes criticized under a merely aesthetical point of view [

30].

The aim of this short research is then to collect some elements towards a final overturn of this position.

3. Repositioning the Political Weight of Public Realm after COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic emergency period forced cities into unprecedented kinds of lockdown, causing a generalized economic, cultural, and social crisis which is expected to cause short-, mid-, and long-term negative consequences. This period, though, has allowed to prove urban agendas in cities all over the world, building new hierarchies in policy making and leading to sometimes radically different priorities from those existing before the emergency [

31,

32].

It is now commonly accepted that the impacts of the rules of social distancing on citizens’ lifestyles have been disruptive, mainly affecting the importance of open space within cities. While previously most cultural, educational, sporting, and leisure-related activities had the possibility to be held indoors, with the rules on spacing all this had to inevitably change with unparalleled promptness [

33].

Presence, availability and also quantity of open public space has therefore become an indispensable indicator for the possibility of development of such activities, fundamental for social relations and the cohesion of local communities. The public outdoor space has therefore proved again to be a downright common, even the most inalienable, ancestral and fundamental one of essential importance for the balance of urban metabolism.

Furtherly, the pandemic has brought back to the attention of the urban agenda the role of public outdoor space in terms of psycho-physical wellbeing of citizens, together with a renewed importance of health itself, not only as an indispensable asset to the life of the individual, but as shared public good. Never before, if not in the face of a pandemic, has the issue of health been so participated among communities where the possibility of safety for one is dependent on the good health of their neighbor and on the correct hygienic behavior of each and anyone, or, in other words, on a common agreement to follow the same, specific good practices inside a social cluster. If in the pre-pandemic era public space had mainly played a role in opposing atmospheric pollution by providing urban greening, after several lockdowns and cycles of social distancing, it is now commonly acquired that an adequate provision of public outdoor space where to practice sports, or even just do some elementary and natural movement, or breathe cleaner air (in a pandemic with air as main transmission vector), allows a significant improvement in the quality of living conditions in most cities [

34].

Another cornerstone of urban life that first entered a crisis after the activation of social distancing was obviously the local public transport. With the necessary reduction in the capacity of public transport, many of the passengers—who could not benefit from smartworking—had to use alternative means of for commuting or essential activities [

33]. To prevent this users from massively turning to private vehicles and causing critical congestions, it became clear that open public space was called to absorb transport necessity and that there was an unprecedented opportunity for such flows to be oriented towards sustainable individual vehicles such as bicycles or electric micro-mobility devices, through owned or shared vehicles [

35].

It is evident that especially large cities, best equipped with urban agendas and financial endowments and made up of a high concentration of people, were most affected by the virus. The limitation of movements has been one of the most effective strategies to contain the contagion, and therefore the debate on proximity and the importance of building urban systems that offer the opportunity to benefit from essential services of daily use within short walking distances—the so-called 15 min city—has been reaffirmed with greater force, starting from its pioneering definition created by the City of Paris [

36] and landing to its Italian adaptations, like the one included in the Adaptation Strategy document issued by Milan in April 2020 [

37].

What emerged, in short, is the urge for the reinforcement of public outdoor space, included—certainly not for the first time—street space in each neighborhood, as one of the most important assets for the relaunch of cities in the post-pandemic era, starting from culture, education, sports, and sustainable lifestyles to ensure high standards of well-being and public health [

38].

4. Learning Cities

4.1. The Case Studies Choice

So, for the reasons already expressed, urban and public space design stay at the center of what has been defined as slow regeneration a sustainable regeneration which take into account the need of people and is aimed at changing the places slowly in order to co-create both new identity of place and its healthy use with and for people according with the times of participation [

39].

To create attractive and sustainable new areas, the contemporary projects of urban regeneration take into account questions related to sustainability and livable public spaces, such as: accessibility, walking and cycling paths, comfortable and safer streets, and pandemic has highlighted the necessity, for these spaces, to be flexible. So, in the following paragraphs, the paper discusses three examples of cities in Italy which are trying to learn by modifying their approach to public spaces spatial planning following criteria already described.

As partially mentioned in the introduction, the choice of the three case study cities (

Figure 1) comes from both analogies and differences in the three contexts, which make the sample significant to provide methodological insights that can be compared and/or exported to other global contexts. The main analogy, as said, is that the three cities belong to the same country and all of them are trying to give their interpretation of the possibilities opened by the introduction of typically bottom-up methodologies (those of tactical urbanism, particularly) inside traditional institutional dynamics of city government. The differences of the three contexts, instead, belong to the categories of:

- −

Scale, Milan being a large city (>1.2 million inhabitants), Bari a medium-to-big-sized city (>315,000 inhabitants), and Taranto a medium-sized one (<200,000 inhabitants);

- −

Socio-economical structure, Italy being strongly divided between North and South under the point of view of the distribution of wealth per capita (where averagely the North doubles the South [

40]);

- −

Typologies of intervention, as Milan and Bari share a similar methodology, while the cases in Taranto add further declinations of possible tactical approaches.

- −

International scope: Milan is an international hub for global fluxes in Italy, largely observed as an innovation leader on urban actions for sustainable mobility and public space, particularly during the pandemic emergency [

41] that hit Lombardy first in Europe, and is involved in an European project about tactical urbanism (see following paragraphs); Bari, on its side, has started an intense dialogue and exchange with other European cities to share methodologies and good practice on urban actions, merging tactical and strategical public space interventions with welfare measures to support social life [

42]. Taranto is one of the major European urban challenges for its developing urban regeneration strategies in a very polluted industrial site at the center of Mediterranean.

With these spectrums of characteristics, the attempt of this research is to portray, at the same time, the specificity of the Italian contexts as well as lessons of general interest and usefully extendable elsewhere.

4.2. “Piazze Aperte” Program in Milano

Unlike other cities in Italy, Milan’s urban structure developed together with its transport infrastructures, whose role grew extremely important since the dawn of the Industrial Age. And still today, regardless of the city’s important progresses towards a more and more efficient public transport network, its configuration shows a strong redundancy of street spaces, dedicated to private vehicular mobility, and a superabundant quantity of parking slots even in-built areas dating back to well before the wide diffusion of private motorized mobility (which inherently implies those parking slots were progressively subtracted to green areas or free pedestrian spaces). Also, even in central neighborhoods, the typical experience of public space is averagely quite poor, with the vast majority of sidewalks finished with plain asphalt, and large portions of even high-quality residential buildings with no public uses of the ground levels. Worrying levels of air pollution complete the description of the Design City, which lost its culture of public space long time ago.

To change this picture, since 2018, Milan has been working towards the realization of a municipal program named “Piazze Aperte” (Open Squares) [

43] dedicated to the conversion of former street and parking areas into public spaces through tactical urbanism techniques, progressively consolidating methodologies for both realization and citizen engagement through the implementation of multiple experimental activity cycles. After its first ones, where the realizations were actively participated by citizens, but still on areas selected by the municipality, since 2019, the program evolved in “Piazze Aperte in Ogni Quartiere” (Open Squares in Each Neighborhood) [

44] and the involvement of citizens extended to every step of the process, structured as follows:

- (I)

A selection phase, where the City issued a call open to free citizens, informal groups, and associations, to propose urban transformations realizable within the tactical urbanism framework. Applicants were provided a kit of admissible interventions (typically paintings, urban furniture, and potted plants) and a list of 52 urban areas available for a transformation (with the possibility to candidate further ones);

- (II)

A proposal phase, where citizens were asked to propose transformations concerning function, aesthetics, and furniture. Interestingly, several groups spontaneously included professional designers to improve the efficacy of proposals. Anyway, regardless of their technical quality or readiness, all proposals were accepted (unless evidently incoherent with the intervention kit);

- (III)

A co-design phase in which citizens were involved in a co-design process to refine their proposals and fit them inside the urban safety regulations and traffic management.

- (IV)

The final realization activity, seeing citizens welcome to actively contribute into the realization of the interventions. Collective painting living-labs were activated with adults and kids, thanks to the use of non-toxic paints and materials.

Currently, the city is in the process of progressively realizing all proposals. It is possible to state the involvement process exceeded expectations, not just as it directly involved more than 200 actors in a quite short time and succeeded collecting at least one proposal on each of the 52 originally available sites, but especially as the proposals included an additional 11 areas, all currently under advanced co-design phase, if not already completed.

What is clearly more interesting in this process, besides its several levels of inclusiveness and public participation, is the attempt to build a strategic framework behind tactical interventions or, better, to understand tactical urbanism as a tool to foster transformations that belong to a strategic vision. In such a theoretic context, the tryouts can stratify a technical as well as shared knowledge in a continuously growing common heritage, through trials and errors and by testing increasingly complex solutions.

In fact, a crucial topic the city is now working on is understanding the opportunities that hide behind the inevitable necessity to finally turn the “temporary” into “permanent” or, in other words, about how to take advantage of time factor as a further experimental possibility. From the one side, some of the earliest Piazze Aperte are now being turned into permanent pedestrian squares through the classical public works procedure and have therefore ultimately entered the urban geography of Milan, closing their life cycle from “beta” to “formal”.

At the same time, though, parallel processes have been activated to enrich the scientific and cultural achievements coming from this experimental season. Since 2019, some interventions have been realized as part of a European project [

45] where Milan is networked with the cities of Amsterdam and Munich together with their technical universities and other actors [

46] in order to share administrative and technical expertise and build a more solid scientific backbone [

47] and a methodological legacy for the strategies behind the interventions. A remarkable output of this project in Milan can be found in the additional level of experimentation that involved a call for artists, realized in 2020 with an unprecedented collaboration between the Mobility and the Culture [

48] municipal departments. As a result, to this call, which collected 43 art proposals for two urban sites, the Roman muralist and illustrator Camilla Falsini was selected to realize two original works of participated, superscale graphic art, freely accessible to the public and dedicated to the identity of two neighborhoods in tumultuous evolution (

Figure 2). These original, site-specific super-illustrations characterize the spaces and help growing interest and curiosity to reinterpret the new areas as fully public squares, consolidating the sense of belonging and fostering different uses, from kids playground to pure contemplation. While this process might apparently seem disconnected from a discourse on permanence, it is instead possible to interpret it as a further attempt to create new values on urban spaces in need of a renovated identity as piazzas, by understanding beauty, art, and culture as immaterial yet incisive elements for the construction of a shared sense of place.

4.3. “Open Space” Program in Bari

On 4 May 2020, the first “hard” lockdown in Italy ended and cities worldwide took advantage of this pause to reorient their urban agendas towards the resumption of daily activities. On 26 May, the City of Bari launched “Open Space”, a “Program on sustainable mobility and public space for the implementation of distancing measures related to the COVID-19 emergency” [

49]. The program is intended to reorient sustainability objectives and, more generally, to test the idea of a city based on resilient communities, by adjusting or accelerating some ongoing processes: fostering sustainable mobility; increasing the allocation of open public space; enhancing greenery and proximity services. The main objectives of the program are oriented towards well-being and public health and social and economic revitalization. The interventions on the urban space made use of tools belonging to tactical urbanism domain, with quick, economic, flexible interventions that are, above all, participated with local communities. Open Space contributes to two main spheres: “A Muoversi” and “A Stare” [

50].

“A Muoversi” includes measures aimed at limiting the number of journeys per day also by strengthening smart working, desynchronizing entry and exit times, and favoring the diversification of movement towards cycling, electric, and pedestrian mobility to compensate for the reduction in the load of local public transport. Among the pilot actions of the program, the redefinition of Zones 30, 20, 10 Km/h for traffic moderation and the creation of a network of pop-up pedestrian and cycle paths were implemented through the typical tactical urbanism techniques, for their inherent advantage in terms of quickness and reversibility.

“A Stare” measures are instead meant to guarantee easier movement and stay for fragile categories as elderlies and disabled people and an equitable access to open public space as a form of enablement for activities currently impracticable elsewhere, with particular interest towards well-being, physical activity and commercial activities lacking in confined space. Under this program, tactical urbanism entered as a means to quickly provide new public spaces and equip existing ones for physical well-being, sporting activities, and food takeaway and consumption within physical distancing regulations. The expansion of public space has been specifically intensified around key neighborhood aggregation spots, like school, parishes, and socio-cultural hubs.

A further experimental action intended to support outdoor life in public space was implemented by identifying a prevalent function or activity directly linked to each Open Space intervention. Mostly, these pivot functions are also economically supported by the municipality within the Open Space framework [

51] and are meant to connect each tactical transformation to the possibility of public space to host cultural events, summer camps, educational activities for the youngers, or to simply support local economies of free time.

After these experiences, it is possible to observe how transferring Anglo-Saxon good practices within Mediterranean urban contexts and, particularly, into the typical structure of lower Adriatic cities, involves several adaptations in terms of contents and procedures that proved unpredictably relevant at the end of the first cycle of the program.

The most relevant element is the location of the interventions within an urban fabric with particular characteristics and specificities. Mostly, tactical urbanism practices are oriented to the transformation of redundant street and parking spaces towards a sustainable use, usually pedestrian-oriented or in general dedicated to leisure and free time (

Figure 3). This can inevitably occur only in urban fabrics characterized by large grids and significant oversizing of mobility spaces—both compared to the traffic flows they hold and the lanes sections that make them up (see for example, Milan’s case study in this paper). Open Space program, instead, intervenes in the most densely built contexts, specifically lacking open public space. In Bari’s consolidated city contexts, even in areas that have been developed in the last quarter of the 1900s, the void between buildings is always extremely reduced, with restricted sidewalks and pedestrian areas and mobility lanes that already equal or barely reach the minimum dimensions required by road codes. This means that the realization of larger spaces intended for pedestrian use, or the inclusion of new spaces for cycle or micro electric mobility, is infrequently possible by just reducing redundant driveway space. Regularly, given the very limited road sections, a drastic, exclusive choice must be made between parking and pedestrian space or, for example, by eliminating a whole lane or a direction of travel to allow the insertion of cycle paths. This circumstance involves much more radical decisions in the sense of a political direction to impart on the transformations of the city and, therefore, requires a broader agreement with local communities.

These transformations, in fact, often subtracting spaces from some (mainly cars) to grant others (pedestrians, cyclists, etc.), determine the development of much harsher conflicts compared to situations where space acquires new functions without losing any. It is interesting, on this regard, to observe how tactical urbanism practices like the well know Barcelonese “Superilla” [

52] imply a specific thought on urban scale that is typically applicable on hyper-dense urban contexts like Bari could be. In these cases, tactical urbanism interventions may act not just as a tool to redistribute unfairly allocated surfaces by downgrading them towards the human scale, but, on the opposite, as a downright strategical method to make tests on how to paradoxically expand the urban scale of contexts in need, and overcome severe dimensional problems connected with congestion that have been giving headaches to planners and politicians in the last 70 years at least.

4.4. Taranto

The Municipality of Taranto is a medium sized city in Southern Italy, which has experienced a long period of economic and environmental crisis [

6] from which it is painfully emerging in a long process of deindustrialization, still in progress, from the monoculture of steel that has characterized the last 70 years. The existing public spaces are the result of a general master plan drawn up in the late 1960s with a rational and modernist approach typical of those years which today shows all its limits with respect to the needs of contemporary life: large empty squares, wide section streets, without cycle paths, designed for the prevalent use of cars.

With respect to this state of the art, a new municipal administration has tried to rethink the development model of the city, heterodirected by the national state for over a century (first with the most important headquarters of the National Navy, then with the largest steel plant of Europe), pursuing self-sustainability, differentiation, and multiplicity of urban economies [

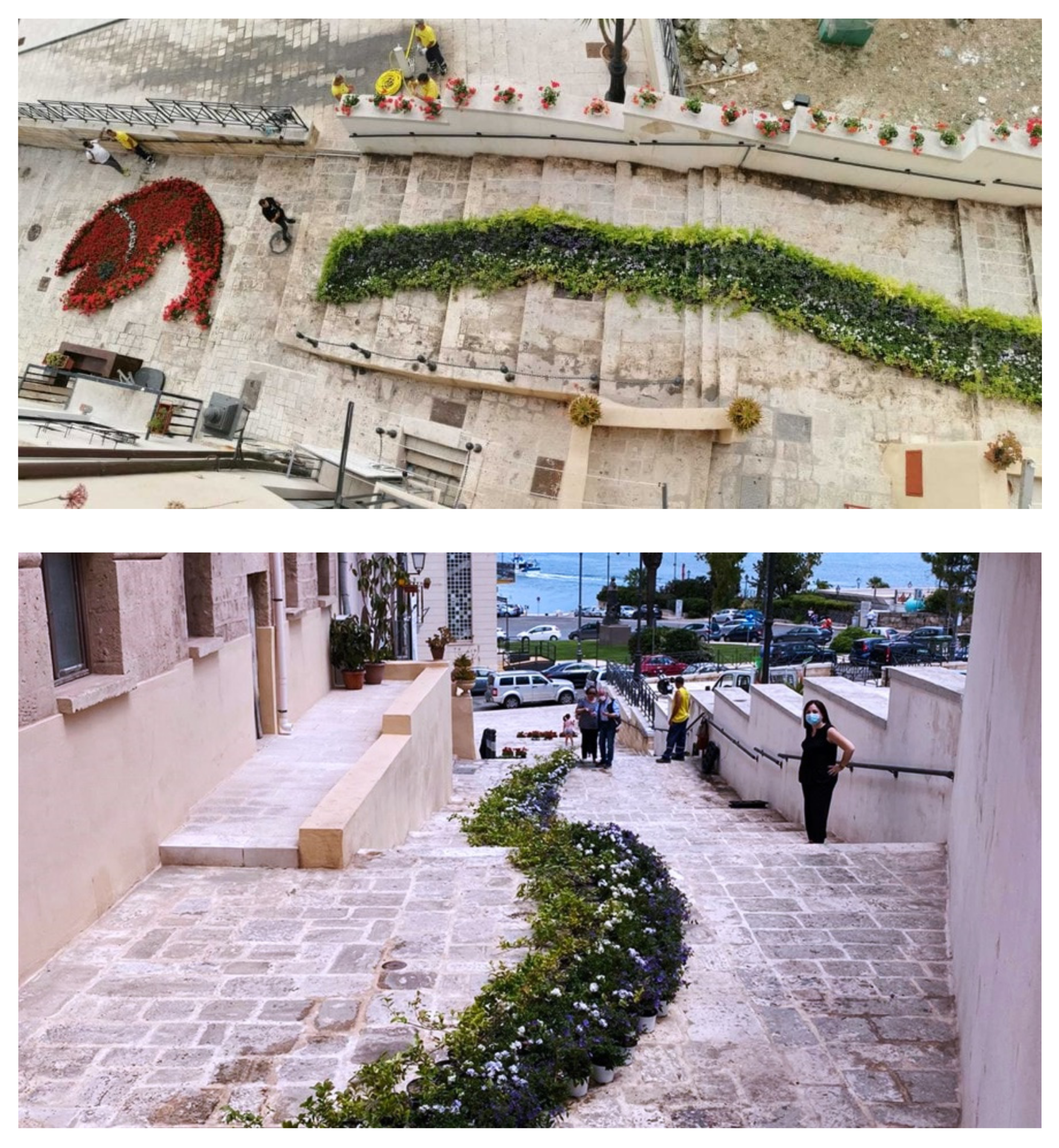

53]. In this strategy, called the Taranto Ecosystem, the role of the public space assumes a fundamental role because it becomes the space for the representation of this desire for change of the established community. The urban regeneration of large suburban districts has been planned, but at the same time small interventions to test different relationship between citizens and common space in a city and in a community that has probably lost the habit of considering the collective space as a property of all of us, on the contrary normally identified with the space of the national state as if it were an external subject and far from the community itself. Starting from these general considerations, in coherence with the concepts expressed in the initial paragraphs, here we present two ways of understanding public space and its relationship with the community. The first transforms the open and public spaces of the historic center into places appropriated by the inhabitants with some specialized operators to guide paths and create parking places, through the use of flowers (

Figure 4). It is a temporary use that lasts only three days, but which helps to change the gaze on these spaces where sometimes cars or engines still circulate, but which due to the materials they are made of and the intimate relationship they have with homes and social functions that often host, in these three days they become a plant link between public and private uses and functions.

In the classification of temporary uses developed by Lehtovuori and Ruoppila [

54], these uses are defined as recurring and, in the case in question, have been repeated every year for about five years now. Often in the literature (for example, the cases cited by Camillo Boano [

55,

56] or [

57,

58]), the temporary occupation of public places is the result of the activity of antagonistic groups, contrasting institutions, which through illegal occupation carry out real protest actions. In these cases, on the contrary, it is the institutions, together with the citizens, who experience different uses of the same spaces, which during the rest of the year are only roads or open spaces of passage. They are opportunities for mutual learning.

The second way of rethinking a public space concerns the streets and in particular those that mark the outskirts of the modern city.

The overcoming of the traditional organization of the streets as spaces mainly dedicated to vehicular flows is now a shared heritage of contemporary architecture and urban planning, but the creation of spaces for reversible cycle and pedestrian mobility, without pretending to be durable but with the intent to first verify the goodness of the solution prepared to understand if it can become a permanent solution, is a fairly recent activity that is fully hinged on tactical urban planning and which becomes an instrument of urban regeneration to the extent that through the experimentation begins a dialogue with the inhabitants and users of these spaces and verifies the correctness of the solutions in the conditions of real use.

In this case, through the inclusion of cycle paths and pedestrian paths (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), even if only drawn on the asphalt road, it transforms a space mainly or exclusively dedicated to cars into a public area where citizens and users move in a new way and acquire mastery of it.

5. Critical Observations and Conclusions

The experiences described, beyond the specific cases, highlight the ongoing process of institutionalization of tactical urbanism interventions and temporary use in urban public spaces. The pandemic has offered important motivations for the experimentation of paths already underway in many cities, accelerating a process of reuse and experimentation of tactical interventions in existing spaces, favored by soil-saving objectives, by the demographic aging and shrinking phenomena.

Following Pasqui’s reflections [

59], we tried to understand if in the three cases treated, the strategic nature of the tactics was enhanced, putting into practice a line of reflection that thinks of tactics as a strategic move, adapting their urban codes for placemaking [

60]. Probably the pandemic has enhanced a top-down approach in some choices and to make some of the solutions tested permanent or more stable, it will be necessary to strengthen the mechanisms of both administrative capacity and social interaction within which the devices are called upon to manifest their effectiveness.

From the point of view of administrative capacity, a necessary critical reflection must be made to mention how, under a certain point of view, the mediation of conflicts from one side and the experimentation of temporary, quick and low-cost solutions from the other, represent the same kind of severe effort for the public administration. In fact, the classical municipal structures hardly adapt in the management of transformations requiring massive use of human resources merely destined to mediation and facilitation, as well as to monitoring works that, even if procedurally lighter than usual public works, still, in their temporary nature, might expose the administration to the accuse of waste of public money, as the resources are allocated on transformations that, sooner or later, will be removed. Therefore, the need to hinge tactical urbanism actions well in a long-term strategy, where temporary experimental interventions anticipate permanent transformations and substantial public works investments, is increasingly consolidating.

From the social interaction side, instead, we can say that it is now of extreme interest to both observe how the new squares will be used and interpreted once permanently transformed and to understand whether some deeper lessons may be learned from the “temporary” dimension of tactical experiments.

Time, indeed, emerges as a crucial element for a complete assessment of these experiments. From one side, transiency highly limits the scope of solutions to be implemented as, for example, the use of natural elements is reduced to short-time installations (like in the case of Taranto) or, at least, to potted plants, reducing the potential benefits on local climate and public health that is rising as a priority as environmental issue become increasingly relevant in the public debate. From the other side, instead, impermanence inherently allows a higher level of audacity and daring, as in the case of the Milanese artistic collaborations. Could this new aesthetics of public space become in any way a durable cultural trait of our cities? Will we miss the bright colors of their experimental phases of our long-term regeneration processes? Will the final, formal transformations leave space for art and creativity, or, at the opposite, the planners will develop forms of semi-permanent transformations, with the advantages of both the approaches, and therefore with both courageous and high-quality solutions? The questions are still open and, in our opinion, testify the richness of opportunities provided by even such light and cheap interventions for the urban debate and, therefore, their multifaceted nature that is still currently far from being completely understood and exploited. Moreover, it will be necessary to verify whether there will be the desired connection between the short time of temporary use projects and the reversibility of tactical interventions with the longtime of long-term territorial regeneration projects.