2.1. Vocational Education and Training

Vocational education and training (VET), which is considered a primary strength for bringing about the sustainability of these programs, is generally referred to as skill-oriented education, in which students are prepared for different trades with the help of hands-on job-specific instructions and occupational experience [

5]. By doing so, not only is the employability time of the students reduced, but their transformation into a vibrant and skillful workforce also takes place, which strengthens their career path [

6]. In this pursuit, we must ensure that the programs are technology-driven and well-aligned with the requirements of the labor market; this will be helpful in exploring the understanding of people and markets with regard to sustainable career growth [

7]. On the other hand, a critical challenge is anticipated: any disparity between the curriculum and the market needs not only increases the employability time of students, but also makes them vulnerable to stress, anxiety, and depression [

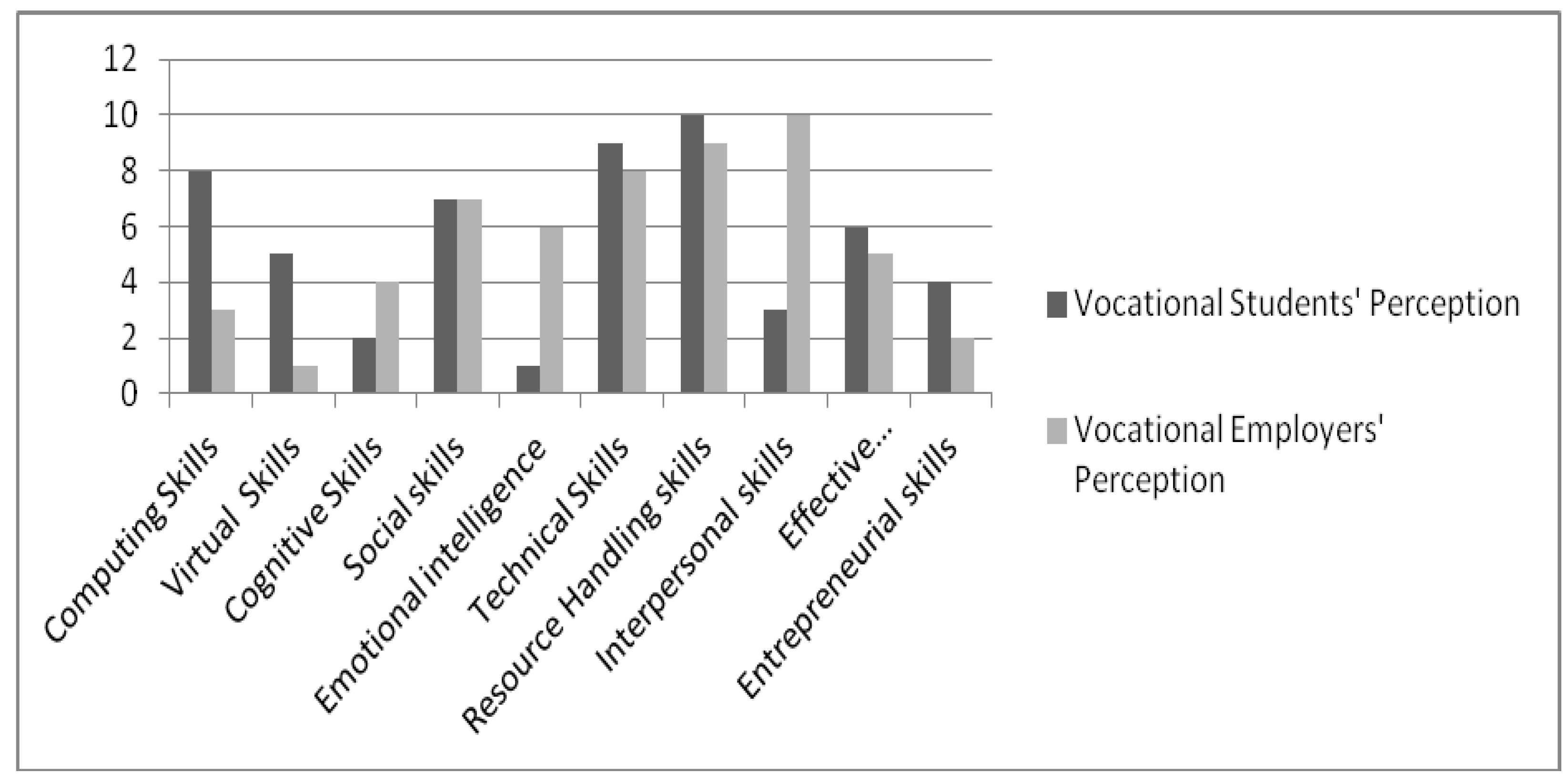

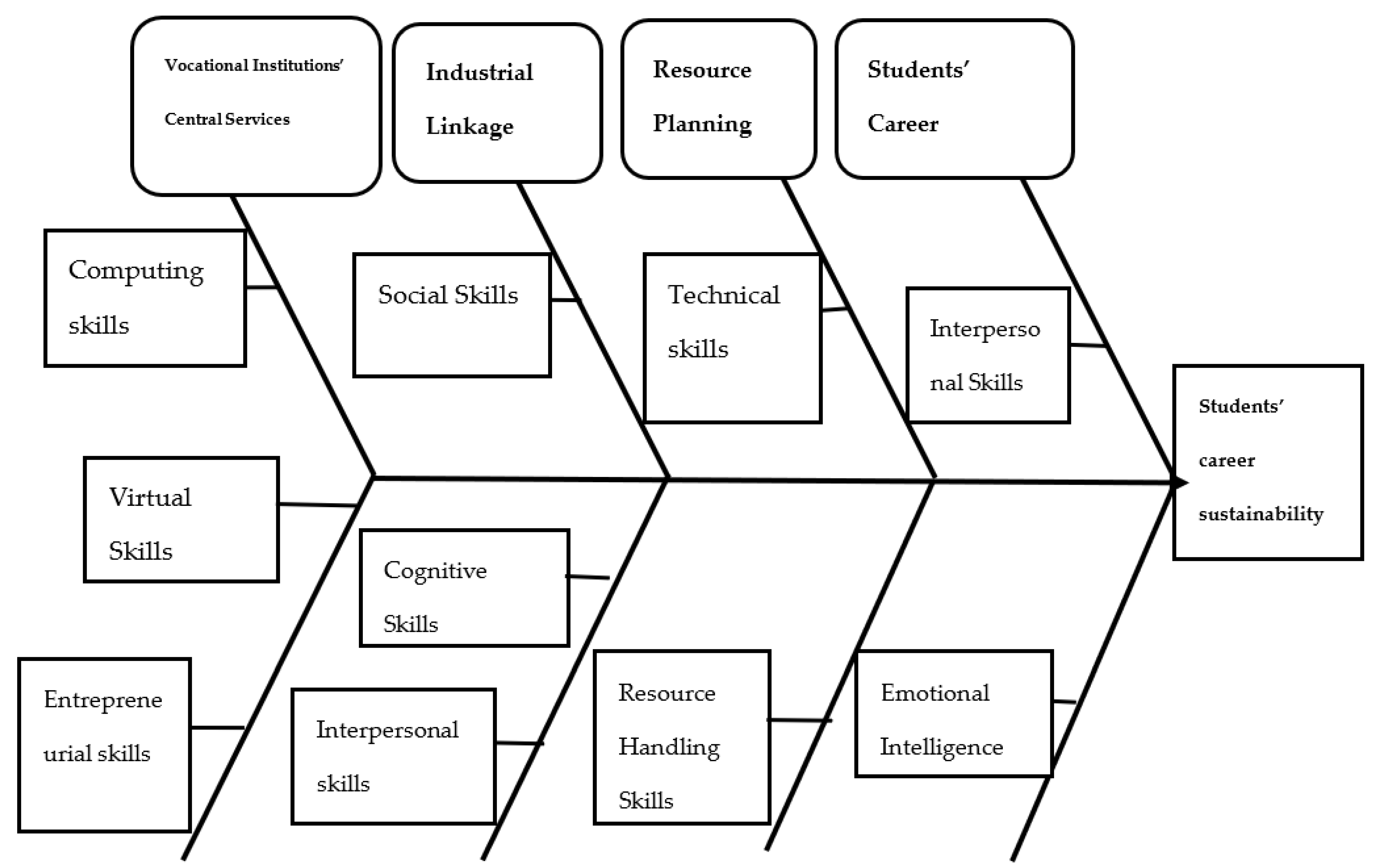

8]. These views are further supported by Ali et al. in their study conducted on 812 vocational students and 129 industrial employers in Pakistan, in which students perceived that their technical skills played an important role in procuring them jobs, while employers placed more importance on their creativity, as well as interpersonal and other soft skills [

9]. A similar study in China indicates a gross mismatch between market requirements and the competencies possessed by graduating vocational students [

10].

2.2. Contemporary Reforms in Vocational Education

Because of the inadequacy of these programs to address the needs of the labor market, an extensive overhauling and consensus-based reforms are required to improve the quality of these programs for practical sustainable development [

11]. In their research, Noor et al. surveyed 453 vocational students in Malaysia and suggest that problem-based and experiential forms of learning play dominant roles in improving student performance, as opposed to conventional theoretical approaches, strengthening career sustainability as well as the self-confidence of the students [

12]. Another study, conducted by Alecxandrina et al. in Romania, proposes that the balance between information and communication technology (ICT) is pivotal in developing the necessary skills and competencies among vocational students in order to provide continuous development [

13]. Moreover, in addition to institutional knowledge, early exposure to industrial processes also generates extra impetus among vocational students and guides them towards sustainable careers, social equity, and economic development [

14]. Similarly, the engagement of industrial experts with vocational students as mentors helps in creating awareness among them about real-world problems, in addition to the evaluation of their employability skills before joining formal employment [

15]. Moreover, collaborative learning between industry experts and course teachers also contributes to increasing student satisfaction by providing a friendly environmental energy towards meeting the goals of a sustainable future [

16]. Meanwhile, Thomas Bolli introduced the concept of education-employment linkage (EEL) and highlights the role of vocational employers in defining quality standards, curriculum design, and classroom education to support sustainability targets [

17].

2.3. Contextual Modularisation of Vocational Education

However, the structure of vocational education experiences varies a lot owing to the diversified requirements of different countries, the individual and social behaviors of vocational students, and industry authorities [

18]. For instance, Switzerland focuses on the combination of school and workplace learning; Singapore engages vocational employers to strengthen their vocational schools; Dutch vocational education registers almost two-thirds of their high school students in various technical and vocational programs; Denmark introduced hundreds of vocational programs to enrich their vocational education; while Korea and Hong Kong emphasize enrolling five and seven percent of their youth in vocational education programs, respectively [

19]. Similarly, in a developing country such as Pakistan, most of the urban area parents/guardians still perceive vocational education as totally worthless and prefer to put their children in alternate fields of higher education [

20]. In this regard, Amin et al. put forward a synthesized approach that highlights the role of educational leaders as pivotal in convincing parents to register their children for these programs from several perspectives [

21]. Although the government of Pakistan has set up the National Vocational and Technical Training Commission (NAVTTC) at the federal level, and Technical Education and Vocation Training Authorities (TEVTAs) at the provincial levels, they are still unable to fill the supply/demand gap of the skilled workforce [

22]. Nevertheless, both public and private sector polytechnic institutes also offer various kinds of VET programs. However, a major portion of technical training is done through an informal system in which a skilled person transfers his/her skill to an apprentice [

23]. Nevertheless, the number of students enrolled in VET programs in Pakistan is increasing. However, because these programs are not relevant to local industry, the graduates face great difficulties in finding timely jobs [

24]. As a result, most of the vocational graduates remain unemployed for longer periods of time, not only impacting their health, but also shattering the confidence level of parents/guardians in these training programs [

25].

2.4. Theoretical Models in Adult Learning

Numerous studies have been consulted to explore the theoretical models that are linked to the sustainability and career adaptability of youth. In the transformative learning theory (TLT) of Mezirow [

26], transformation through different variations is been discussed in relation to adult education. The implementation of transformative learning theory in vocational education is paramount because of the expansion of one’s consciousness that ultimately brings clarity of purpose to learners. However, Schnep et al. emphasize the importance of personal and sociocultural contexts and propose adding the element of context as a fourth foundation in the transformative learning theory [

27]. Similarly, the Crites’ model of career and vocational development [

28] is widely implemented and applied in the current research to suggest the best possible strategies for the guidance of vocational employers and technical institutions. The vocational development inventory by Crites helps students to make appropriate vocational plans, and research conducted by Ertelt et al. further highlights the holistic role of apprenticeships for sustainable career development [

29]. Furthermore, York’s USEM employment capability structure model [

30] not only guides vocational students in self-assessing their employability skills, but also helps them in organizing the complexities of career development. The determinants of the USEM model are further validated by Bennet and Ananthram, with the help of the multifactor perceived employability scale, in which the self-efficacy of students is used to determine their metacognition and learning responses. In this way, the aforementioned models are used to integrate the skills learnt at vocational institutions along with the needed skills that count for their sustainable future.

As is evident from the literature, various studies have been performed in order to observe the effectiveness of these programs; however, most of these studies are context-specific and were carried out with regard to the general efficacy of these programs. It is evident that a strong connection between the students’ employability (SE) and employers not only reduces stress among students, but also minimizes the chances of them taking risks in the selection of their careers [

31,

32]. Thus, the present study aims to observe the perception gap, with regard to employability skills, between vocational students and industrial employers in the context of a developing country, where a major portion of the population is still living in rural areas and any delay in their employment not only creates stress and anxiety among them, but also undermines the credibility of these vocational institutions as well. Current research primarily focuses on heightening the creditability of vocational institutions in rural, as well as urban, areas, where the main focus is to uplift the employability rate. Therefore, this study explores whether any gap exists between the perception of employers and vocational students, rather than looks at the impact of living in urban/rural areas and studying in public/private institutions. This recent study focuses on the life course imprints of vocational education on employment, arguing that there is a vocational decline and that having occupation-specific skills is a benefit at the start of a career.

2.5. Research Hypotheses

The three following research hypotheses were developed for further analysis. For this purpose, the determinants were taken from the appropriate theoretical models: the transformative learning theory (TLT) of Mezirow [

33]; Crites’ model of vocational adjustment [

28]; and York’s USEM employment capability structure model [

30] in order to validate the research hypotheses. However, it is vital to understand the difference between general and specific skills, introduced by Becker in human capital theory [

34]. Specific skills have direct connection and validity within specific occupational domains, whereas general skills can be applied in a variety of contexts. Later on, Shavit and Miller classified the domains into specific vocational skills and general skills [

35]. The questionnaire of this study is based on the above theoretical models.

Moreover, the present study’s research hypotheses are based on the theory and notion of the perception gap. The concept of employability skills used in the literature is a construct that “grows by accretion with the addition of new sub-constructs”, argues Smith et al. [

36]. Since no single party, out of the ones identified in the literature review, and especially the three above-stated theoretical models, has control over this construct, it is subject to different interpretations from those involved in the aforementioned processes, including, namely, education system policymakers, employers, trainers, and students. As definitions of employability have grown in recent years, many studies have investigated reasons for the disproportions between the objectives of the education system and the requirements of employers. Leveson [

37] suggests that the problem could be one of perception, specifically, differences in the understanding of the language that underlies the whole employability theoretical structure. A lack of understanding between the interested bodies may lead to potential discrepancies in the aims of competency-based vocational education. Sin and Neave [

38] claim that, “as a concept, employability commands little consensus. Rather it is interpreted in the light of each interest group’s concerns as a floating signifier”. It is, therefore, exactly this development, with employability skills being a fluctuating signifier among the interested parties identified in the above-stated theoretical models, that inspires the herein settled main research questions:

What are vocational employers’ and students’ perceptions of desirable employability skills, and how do they converge or diverge?

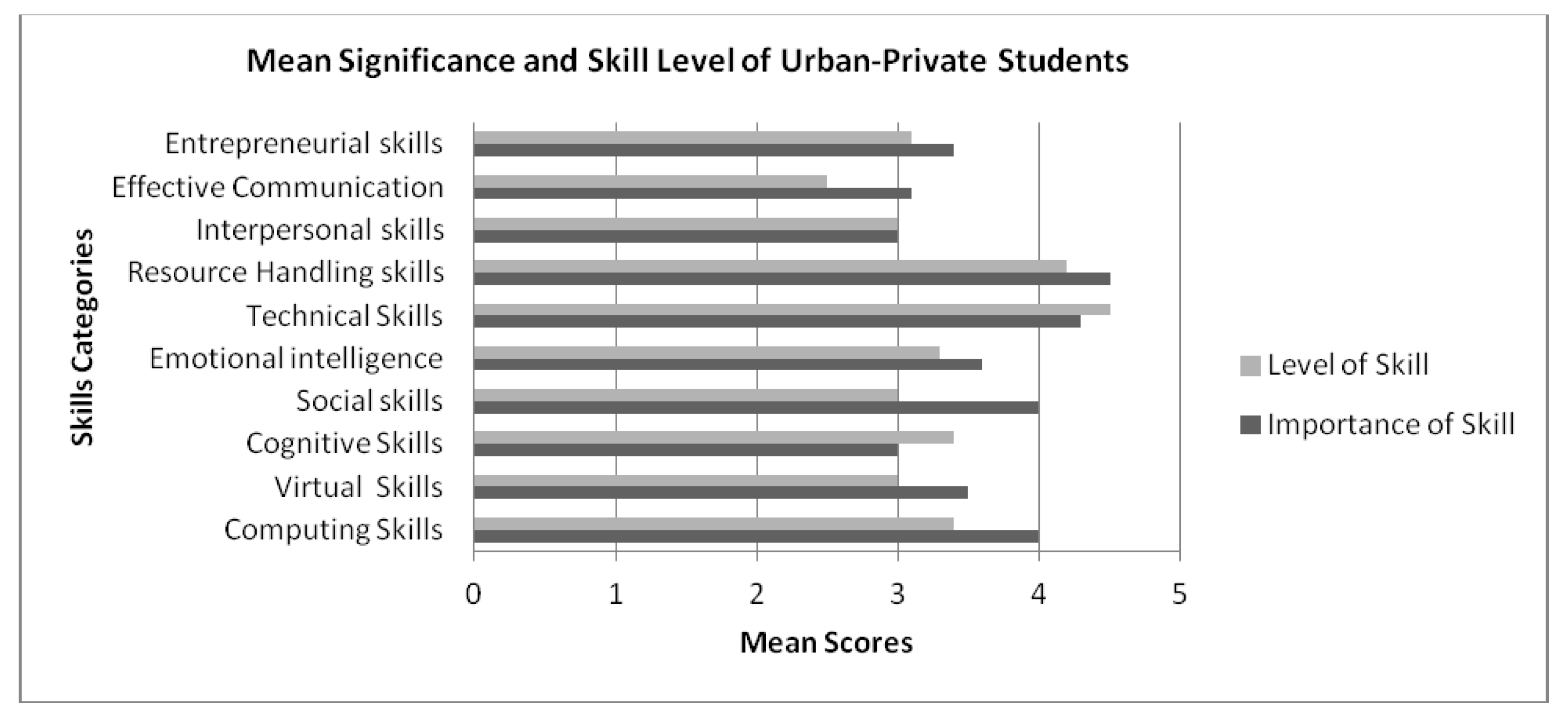

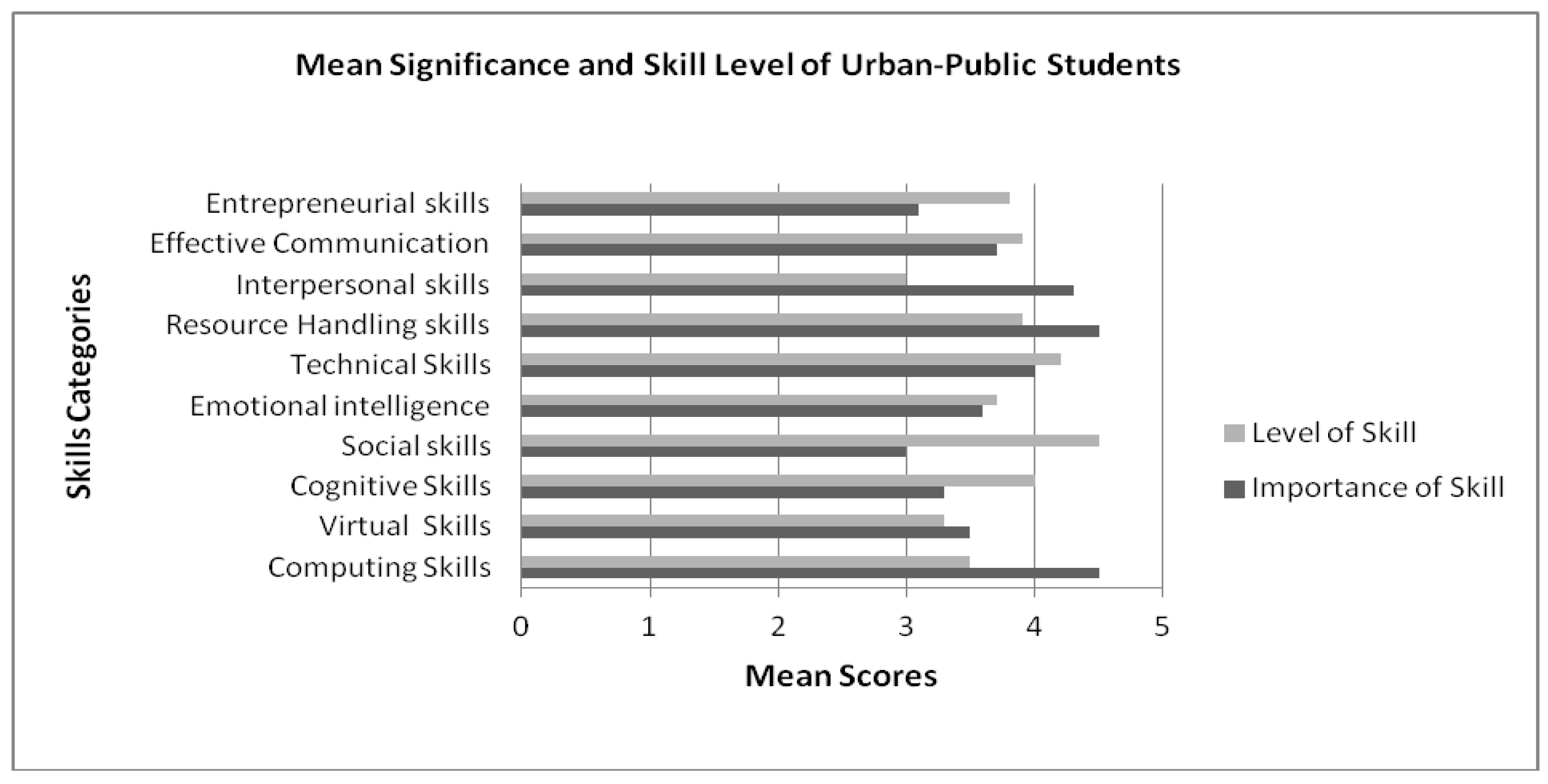

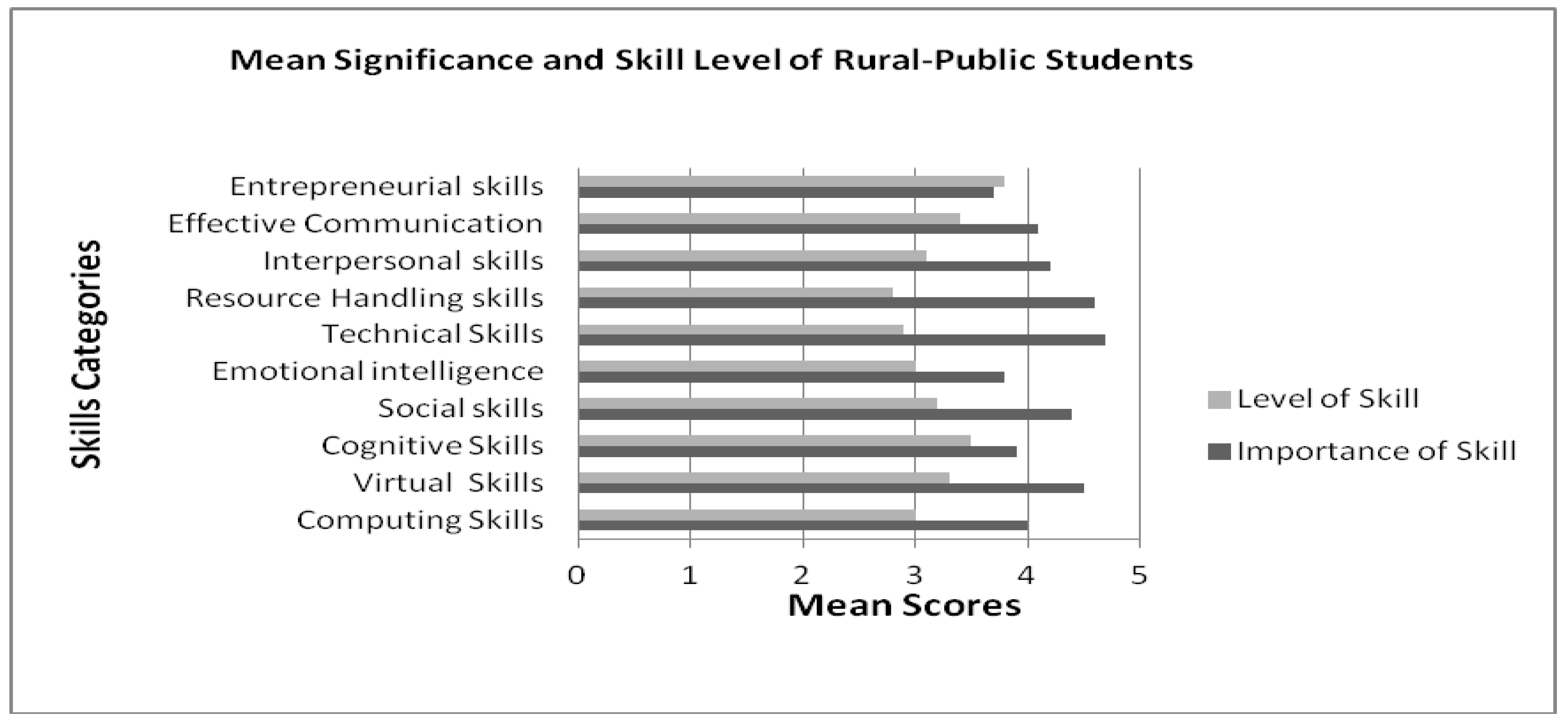

What are the perception gaps of rural/urban areas and public/private institutions regarding desirable employability skills?

Of course, there are many other hypotheses that could be investigated in the context of vocational training because of the combination of the many interested and involved bodies. However, the present study has focused on the above main research questions, analyzing the situation in developing countries.

However, one critical question is herein raised on why the present study and its hypotheses are important in the field. The reason for conducting such studies with regard to identifying the possible perception gaps between employability skills is because convergence is needed in the perception of all interested parties if sustainability is the goal in vocational training. In order to achieve such convergence, a subsequent leapfrog step should be followed, namely, the definition of suitable strategies for closing the gaps between the perceptions and interpretations of the different involved bodies. The properness of such strategies can be measured by the relevant gaps. The contribution of the present study lies in the identification and measurement of such perception gaps between the involved parties based on the factors defined in the three previously mentioned theoretical models, namely, the transformative learning theory (TLT) of Mezirow [

33], Crites’ model of vocational adjustment [

28], and York’s USEM employment capability structure model [

30]. The authors aim at presenting, in the near future, a sequel of this work measuring the impact of suitable strategies, such as the ones defined in

Section 5 herein, in the convergence of the perceptions of the different interested bodies regarding vocational-training-based employability skills.

On the basis of the above-mentioned theories and analysis, the following three hypotheses were developed to explore the impact of the perception gap between industrial employers and vocational students. The hypotheses formulated assume the connectivity between the occupational-specific education system and current job/industry demands, so as to define the mechanism of vocational institutions in work transition.

Hypotheses 1 (H1). A significant perception gap exists between vocational employers and vocational students with regard to employability skills.

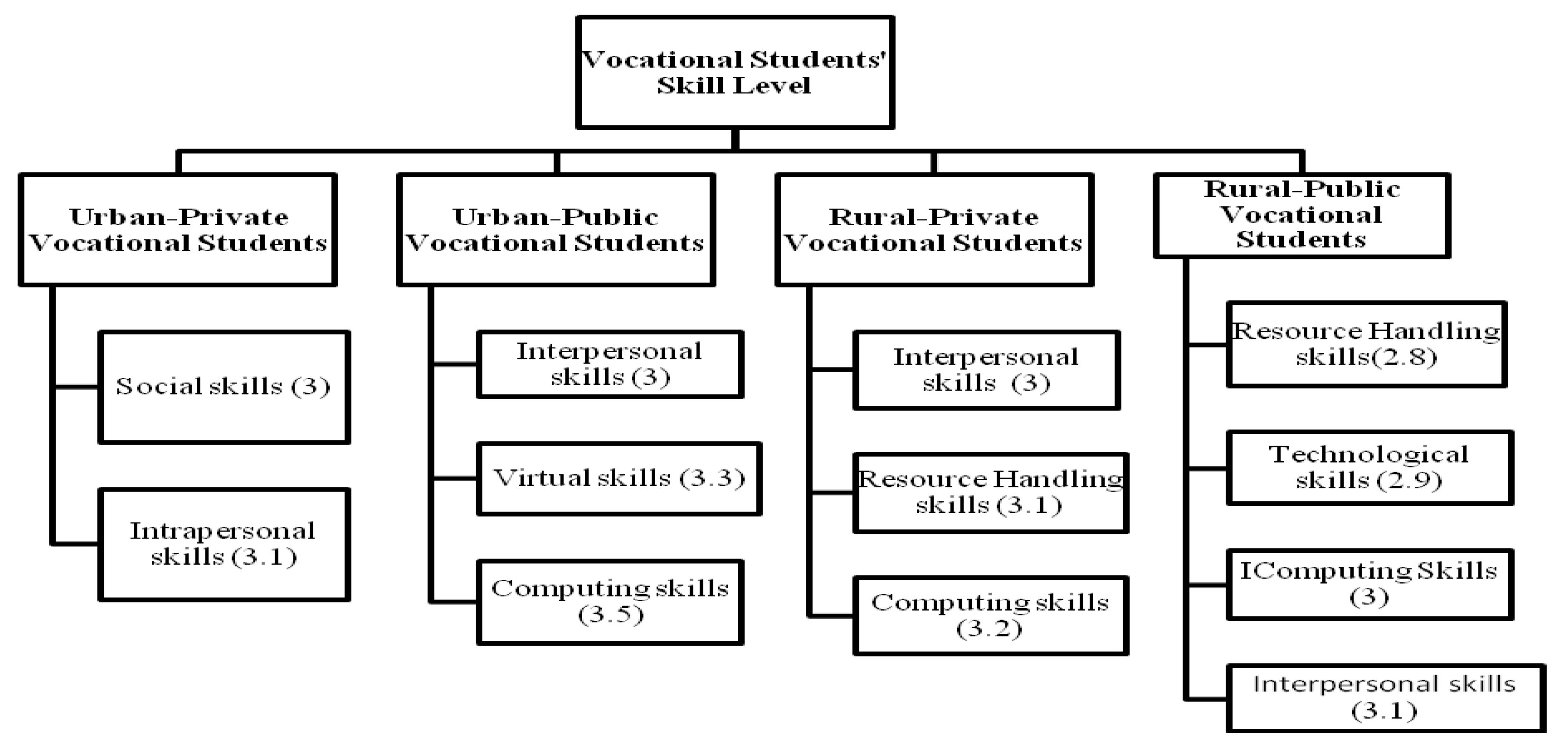

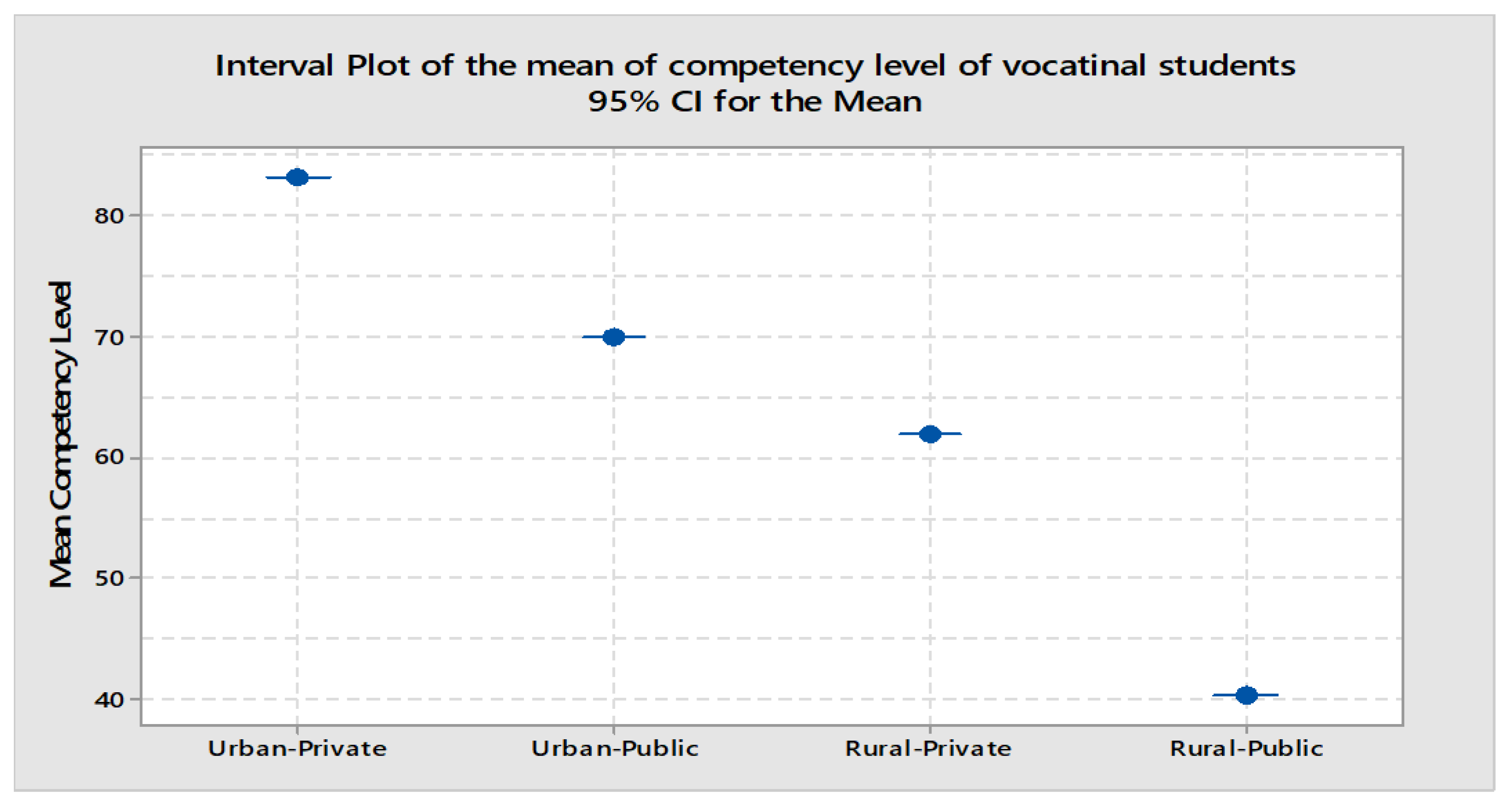

Hypotheses 2 (H2). Living in urban vs. rural areas creates significant differences with regard to the perception of employability skills.

Hypotheses 3 (H3). Studying in public/ private vocational institutions creates a significant difference in the competency levels of employability skills.