Community Health and Public Health Nurses: Case Study in Times of COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

2. Materials and Methods

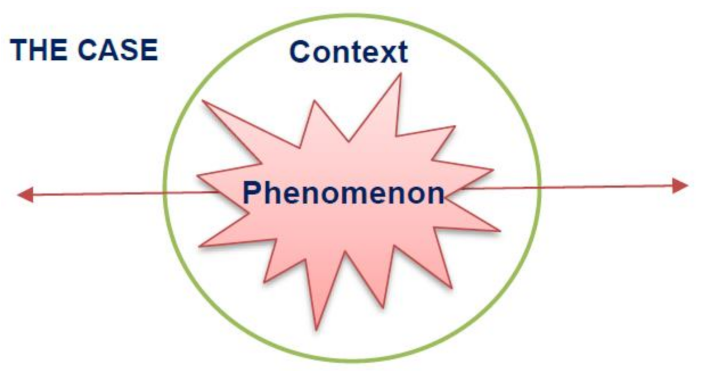

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Treatment and Analysis

2.6. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. The First Category

3.2. The Second Category

3.3. The Third Category

3.4. The Fourth Category

3.5. The Fifth Category

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carvalho, E.C.; Souza, P.H.D.O.; Varella, T.C.M.M.L.; Souza, N.V.D.O.; Farias, S.N.P.; Soares, S.S.S. COVID-19 pandemic and the judicialization of health care: An explanatory case study. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2020, 28, e3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.C.; Lai, Y.H.; Tsay, S.L. Nursing perspectives on the impacts of COVID-19. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 28, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granel, N.; Bernabeu-Tamayo, M.D. Mapping nursing practices in rehabilitation units in Spain and the United Kingdom: A multiple case study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, C.B.; Peduzzi, M.; Costa, M.V. Nursing workers: Covid-19 pandemic and social inequalities [editorial]. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2020, 54, e03599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, E.G.; Felix, A.M.S.; Nichiata, L.Y.I.; Padoveze, M.C. What is the nursing research agenda for the COVID-19 pandemic? Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2020, 54, e03661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, C.; Henriques, M.A.; Costa, A. Vigilância epidemiológica: Ano internacional do enfermeiro. In Proceedings of the Congreso Virtual de la Sociedad Española de Epidemiología (SEE) y da Associação Portuguesa de Epidemiologia (APE), Bilbau, Spain, 21–23, 29–30 October 2020; Gac Sanit. 34 (Espec Congr). p. 199. Available online: https://static.elsevier.es/miscelanea/congreso_gaceta2020.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Osingada, C.P.; Porta, C.M. Nursing and sustainable development goals (SDGs) in a COVID-19 world: The state of the science and a call for nursing to lead. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Manifesto for a Healthy Recovery from COVID-19: Prescriptions and Actionables for a Healthy and Green Recovery. 2020. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/publication-who-manifesto-healthy-recovery-covid-19-32955 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Cunha, C.; Costa, A.; Henriques, M.A. The public health nurse’s interventions and responsibilities in Portugal: A scoping review. Rev. Enferm. UERJ 2019, 27, e37214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.; Costa, A.; Henriques, M.A. Community health and public health nursing: A systematic literature review. Rev. Gestão Saúde 2020, 11, 80–96. Available online: https://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/rgs/article/view/29414 (accessed on 20 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, T.; Hadzikadic, M. The fundamentals of complex adaptive systems. In Complex Adaptive Systems. Understanding Complex Systems, 1st ed.; Carmichael, T., Collins, A., Hadžikadić, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume VIII, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ordem dos Enfermeiros. Regulamento nº 428/2018, Competências Específicas do Enfermeiro Especialista em Enfermagem Comunitária na Área de Enfermagem de Saúde Comunitária e de Saúde Pública e na Área de Enfermagem de Saúde Familiar. 2018. Available online: https://dre.pt/pesquisa/-/search/115698616/details/normal?l=1 (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, LA, USA, 2009; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, LA, USA, 2018; p. 319. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto-Lei nº 28/2008. Diário da República: I Série, nº 38. 2008. Available online: https://data.dre.pt/eli/dec-lei/28/2008/02/22/p/dre/pt/html (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An. Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, C.; Henriques, M.A.; Costa, A. Health research and innovation: Community health and public health nurse interventions. Rev. ROL Enferm. 2020, 43 (Suppl. S1), 32–42. Available online: https://e-rol.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/IC_RESEARCH_INNOVATION_DEVELOPMENT_NURSING-2019.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Guedes, V.M.S.; Figueiredo, M.H.S.; Apóstolo, J.L.A. Competencies of General Care Nurses in Primary Care: From Understanding to Implementation. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2016, 4, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- United Nations, UN News. Year of the Nurse and the Midwife Highlights ‘Backbone’ of Health Systems. 2020. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/01/1054531 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Haron, Y.; Honovich, M.; Rahmani, S.; Madjar, B.; Shahar, L.; Feder-Bubis, P. Public health nurses’ activities at a time of specialization in nursing—A national study. Public Health Nurs. 2019, 36, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffer, M.A.; Keller, L.O.; Reckinger, D. Public health nursing activities: Visible or invisible? Public Health Nurs. 2015, 32, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.; Lee, H.; Yoon, S.; Kim, Y.; Levin, P.F.; Kim, E. Community health needs assessment: A nurses’ global health project in Vietnam. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2018, 65, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagan, I.; Shachaf, S.; Rapaport, Z.; Livne, T.; Madjar, B. Public Health Nurses in Israel: A case study on a quality improvement project of nurse’s work life. Public Health Nurs. 2017, 34, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, M.E.; Costello, J.; Gremel, K.; Schwager, J.; Blanchette, L.; Malloy, T.E. Political astuteness of baccalaureate nursing students following an active learning experience in health policy. Public Health Nurs. 2012, 29, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temido, M.; Dussault, G. Skill mix between physicians and nurses in Portugal: Legal barriers to change. Rev. Port Saúde Pública 2014, 32, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, M.; Besoaín, A.; Rebolledo, J. Social determinants of health and disability: Updating the model for determination. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Sobrinho, R.A.; Zilly, A.; Silva, R.M.M.; Arcoverde, M.A.M.; Deschutter, E.J.; Palha, P.F.; Bernardi, A.S. Coping with COVID-19 in an international border region: Health and economy. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2021, 29, e3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petiprin, A. Nursing Theory. Neuman’s Systems Model. Available online: https://nursing-theory.org/theories-and-models/neuman-systems-model.php (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Health in Portugal 2018. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpgid=ine_inst_infografia&INST=427173770&xpid=INE (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Varghese, J.; Blankenhorn, A.; Saligram, P.; Porter, J.; Sheikh, K. Setting the agenda for nurse leadership in India: What is missing. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, R.R.; Duggan, K.; Allen, P.; Erwin, P.C.; Aisaka, K.; Yang, S.C.; Brownson, R.C. Preparing public health professionals to make evidence-based decisions: A comparison of training delivery methods in the United States. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Categories | Subcategories | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| The knowledge of the competencies by the nurses | What the nurses know about the determination of their competencies The competencies the nurses know about | - knows whether competencies are determined - knows who determined them - knows what they are - which ones they know |

| The actual interventions and the competencies prescribed | - relates activity with indicators - evaluates the health/community - contributes for capacitation/groups - integrates/coordinates programs - implements objectives/PNS - participates in epidemiological surveillance | |

| The practice of the nurses systematized in interventions | The practice of the nurses and relation with training The importance of interventions The contributions of the nurses to the unit | - his/her intervention is important - do what he/she was prepared to do - contributions to/definition of activities - importance/activities unit - what is done in practice - attributed activities |

| What facilitates or makes the performance of the competencies difficult | The nurses and the relation with work What is difficult and what is easy The nurses and public health | - would continue or change - what contributes/performance - what would change/good performance - what would change/SP - how do you feel/working with others - working alone/team - benefits/advantages of your presence - what makes action difficult - problems, dilemmas/faced |

| Legal framework and regulations identified by the nurses | - knows the regulation - knows which regulation takes precedence |

| Categories | Strategies | Techniques | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propositions | Emerging Data | Patterns | Hypotheses | |

| 1st The knowledge of the competencies by the nurses | The nurses understand their competencies, not all of which are implemented by all nurses [18] | The nurses know well that there are competencies that are defined and know them | The competencies that are understood the most may reflect more theoretical knowledge. The competencies that are understood the least may signify distancing from them [18] | We have come to believe that the specialized nurses in community health and in public health, despite not having the same relation with all competencies, put most of them into practice |

| 2nd The actual interventions and the competencies prescribed | The importance of the intervention of the nurses as the backbone of any health system [19] | The nurses are aware of interventions that correspond to their specific competencies, even though they are not equally involved in all of them | Most public health nurses are mainly engaged with vaccination [20] | Vaccination does not especially stand out in terms of prevalence, but it is the intervention that some highlight the most |

| 3rd The practice of the nurses as systematized in interventions | Nurses are involved in many activities to prevent diseases and contribute to the health of populations. Their activities are not always visible to the public or to political decision makers [21] | Nurses feel that their activities are important for the unit and performs several interventions | It stands out that understanding the health needs, either from the perspective of the provider or from that of the receiver, is very important to prioritize health issues and to improve the most adequate interventions for local situations [22] | It is apparent that the nurses are available for a wide range of activities. Although well prepared, they often seem to be limited by what they are assigned to do. |

| 4th What makes performance of the competencies easy or difficult | To trace a plan to go towards the proposals of nurses to reorganize roles, reinforce communication and work relations with management, and extending the limits of the practice of nursing and public policy [23] | The nurses highlight that they feel good where they are and doing what they do. They point at personal characteristics, such as advantages, and perceive some organizational difficulties | It is recommended that the development of the nurse practitioner as a community expert for response at the individual, community, and population levels including addressing social determinants of health is prioritized [20] | Nurses, apparently, feel prepared and willing to work with others. However, they seem to feel more conditioned by external factors, such as the lack of resources or even of recognition |

| 5th Legal framework and regulations identified by the nurses | Experiences with learning public policies can increase the knowledge and the competencies of nurses, which is necessary for them to influence public policies [24] | The nurses have knowledge about the regulations from the Nurses Order | There will be a normative space for a more effective use of the competencies of the nurses, which may contribute to the Portuguese health system to perform better [25] | It was shown that the knowledge of nurses about regulations and their interest in them is important, among other reasons because regulation changes can depend on their contribution |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cunha, C.; Henriques, A.; Costa, A. Community Health and Public Health Nurses: Case Study in Times of COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011149

Cunha C, Henriques A, Costa A. Community Health and Public Health Nurses: Case Study in Times of COVID-19. Sustainability. 2021; 13(20):11149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011149

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunha, Carmen, Adriana Henriques, and Andreia Costa. 2021. "Community Health and Public Health Nurses: Case Study in Times of COVID-19" Sustainability 13, no. 20: 11149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011149

APA StyleCunha, C., Henriques, A., & Costa, A. (2021). Community Health and Public Health Nurses: Case Study in Times of COVID-19. Sustainability, 13(20), 11149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011149