Abstract

In social enterprises, which are hybrid organizations that create social and economic values, the role of leaders is important to achieve goals. However, prior research on social enterprises overlooked the importance of a leader, and some research that considered leadership was insufficient to concern the characteristics of social enterprises. This study aims to find whether there is no problem in applying the leadership emphasized in a profit-firm to a non-profit-firm such as a social enterprise, since social enterprises pursue economic and social objectives simultaneously. To do so, we examined the effects of four leadership styles (transactional leadership, transformational leadership, servant leadership, and entrepreneurship) used mainly in commercial enterprises on the performance of social enterprises. In review of prior studies, it was assumed that transactional leadership would not have a significant effect on performance, and the other three kinds of leadership were hypothesized to have a positive effect on performance. Additionally, to clarify the relationship between leadership and performance of social enterprises, leader trust and calling were considered as mediators. Using the list of Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency, questionnaires were distributed via e-mail to employees of 318 social enterprises located in Seoul, and 251 copies were collected and analyzed. The results of this study show that transactional leadership only affects economic performance and does not show significance with the rest of the variables as was expected. Transformational leadership had positive relationships with variables considered as performances of social enterprises, and the mediating effects of leader trust and calling were also verified. Entrepreneurship was positively related to three performances of social enterprises, but servant leadership had a positive relationship with organizational commitment. This study contributes to highlighting the need for research to find appropriate leadership styles that focus on the characteristics of social enterprises.

1. Introduction

The interest in social enterprises, companies established to achieve social goals, continues to grow as the community demands that companies more actively implement social responsibility and ethics. Unlike for−profit companies that are concerned only with economic profits, social enterprises must constantly have balance and tension between economic profits and social goals. Because of this, the organizational identity of social enterprises is complex and has more difficulties [1,2,3]. Smith et al. [4] insisted that the social and commercial sides of a social enterprise are not isolated from one another. They drew on paradox research to build a theory about the challenges and associated skills for effectively managing the tensions emerging from the juxtaposition of social mission and business outcomes. Pache and Santos [5] presented cases of how social enterprises were internally integrated even though the two values (social, commercial) were logically different from each other. Ko and Liu [6] suggested social enterprise as the legitimacy of a socio−commercial business model. Nevertheless, social enterprises are being called on to solve more problems in the community and implement the interests of more stakeholders [7]. There is an increasing need for research on how to successfully run social enterprises.

Recently, the importance of leadership is emphasized when solving the distrust of sustainability of social enterprises and to foster successful social enterprises [8,9]. As in all organizations, leadership in social enterprises is essential to organizational growth because it can have a key impact on organizational performance and organizational development during the period of organizational formation or growth [10,11]. Pasricha et al. [9] regarded social enterprises as an organization to fulfill corporate social responsibilities and connected it with ethics, insisting that ethical leadership is the leadership that social enterprise managers should possess. Newman et al. [8] examined the effect of servant leadership and entrepreneurship on social enterprise innovation and organizational commitment. Research on what type of leadership style is appropriate insists that leadership changes are needed according to the development stage of social enterprises [12,13]. However, Smith et al. [4] could not show empirically that their logic was correct, and Pasricha et al. [11]’s research had a limitation in that they considered social enterprises’ activities as too ethical. Newman et al. [8] has shown that among the various leadership styles, specific leadership affects the social enterprise’s members and performance, and that the existing leadership style can be applied to the social enterprise. However, it did not show whether this is more efficacious. Therefore, investigating the relative influence of various leadership styles on the attitudes and behaviors of employees is important as a way to improve performances of social enterprises [8,14].

The purpose of this study is to find out empirically what leadership style is appropriate for social enterprises. This research also aims to systematically analyze the influence of a social entrepreneur’s leadership on performance considering the mediating effects.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis

2.1. Characteristics of Social Enterprise

The definition of social enterprise can take many forms, depending on the legal and cultural differences of each country. However, an important criterion is achieving social goals in profit−making through commercial activities and in the distribution of operations and profits [3,13]. Based on these criteria, the UK’s DTI [15] defines a social enterprise as a company that pursues social goals first, rather than creating maximum profit for shareholders and owners. Social enterprises are also defined as companies where the profits are primarily reinvested in the company or in the community to achieve social goals.

In Korea, Article 2 of the Law on the Promotion of Social Enterprises, enacted in July 2007, refers to social enterprise as a company pursuing social purposes such as providing vulnerable social groups with social services or jobs to improve the quality of life of the local residents. Additionally, this law defines a social enterprise as a company which reinvests profits in the business or the local community, putting priority on pursuing social purposes rather than on maximizing profits for shareholders or the owner of the company [16]. In addition, it categorizes social enterprises into job−creation type, social service provision type, mixed type, other types, and local community contribution type, according to the type and degree of social purpose [16].

- Social service provision type: The main purpose of the enterprise is to provide vulnerable social groups with social services.

- Job creation type: The main purpose of the enterprise is to offer jobs to vulnerable social groups.

- Mixed type: Social service provision type + Job creation type

- Local Community Contribution Type: An enterprise which contributes to the improvement in the quality of life of the local community.

- Other (Creative/Innovative) type: A social enterprise of which realization of social purposes is difficult to judge based on of the ratio of employment or provision of social service.

Borzaga and Defourny [17] classified social enterprise characteristics by dividing them into social and economic standards as Table 1. A social enterprise includes both the characteristic of the company seeking profit and the social aspect prioritizing publicness, as the form of a new enterprise by the social economy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Social Enterprise.

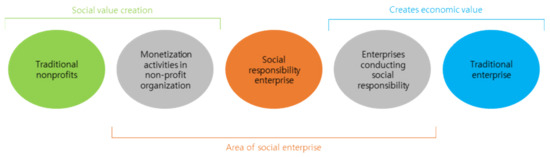

The Social Enterprise Coalition [18] presented three characteristics of social enterprises as Figure 1. First, enterprise orientation is aimed at the production of products and sales and competing in the market. Second, social aims have clear social objectives such as job creation, training, and provision of community services. Third, social ownership: as an autonomous organization whose ownership structure is based on stakeholder engagement, the profit is distributed to stakeholder groups or used for the community. According to the characteristics of the social enterprise and looking at its position in the spectrum between non−profit and for−profit enterprises, social enterprises are located between the traditional non−profit and for−profit enterprises.

Figure 1.

Position of Social enterprise (Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency). (Source: https://www.socialenterprise.or.kr/social/ente/concept.do?m_cd=E001, (accessed on 1 October 2021)).

Dees et al. [19] describes the social enterprise spectrum between pure philanthropy and fully fledged forprofit corporations in terms of motives, methods, objectives, and the attribution of income/profit as Table 2.

Table 2.

The Social Enterprise Spectrum.

Looking at the status of social enterprises in Korea, 2983 social enterprises have been certified by the Ministry of Employment and Labor in 2021 since the Social Enterprises Promotion Act was implemented in 2007 [16].

2.2. Social Enterprise and Leadership

In general, leadership in a company is a key variable for improving and achieving performance. Although the purpose of social enterprise is characterized by both economic and social considerations, the aspect of performance is the same as that of general enterprise. Waddock and Post [10] argued that even a social enterprise for solving social problems needs to be concerned with leadership to improve economic and social performance, and they viewed the leadership characteristics of social enterprise as follows. This provides the potential for raising public awareness and the next goal of the necessary resources. Cornelisson et al. [9] emphasized social aspects and raised awareness of the goal of the group by inducing the dedication of members. Pasricha et al. [11] pointed out that little research has been conducted to identify the leadership needed for these companies having an interest in social enterprises to achieve their objectives.

Following this trend, some studies have been conducted to discern what leadership is appropriate for social enterprises. Austin et al. [13] suggested appropriate leadership according to the development stage of social enterprise. Concerning the growth stage, Nam [20] also argued that social enterprises can be developed by dogmatic leadership in the initial stage, directive leadership in the formalization stage, democratic/participatory leadership in the development stage, and political leadership in the social integration stage. Oh [21] suggested through qualitative research that transformational leadership is needed in the early stages and different leadership is needed depending on individual circumstances in the growth stage. Research claiming the need for leadership change in accordance with the development stage of social enterprises is meaningful in that it showed the right style of leader in each stage. Cornelissen et al. [9] found that leadership helps to facilitate ongoing adaptation and helps members of the organization to become progressively better able at combining multiple objectives and values as part of a shared hybrid identity.

However, these studies are limited in focusing on the items necessary to overcome the situation of the company rather than leadership, which is the same limitation of previous studies showing that the leadership should be different for each life cycle. Even concerning the same stage, they could not draw a unified conclusion, insisting that different leadership is needed depending on the situation. In addition, Borzaga and Defourny [17] argued that the Y−type leader, which combines McGregor’s XY theory with a positive attitude, which encourages participation or learning and accepts suggestions and criticisms, is suitable for social enterprises. However, these arguments did not overcome the limitations of the simple dichotomy of human essence, the critical point of McGregor’s XY theory.

This study aims to identify the leadership styles suitable for social enterprise among the four main leadership styles presented in previous studies: Transactional Leadership, Transformational Leadership, Servant Leadership, and Entrepreneurship; focusing on whether the organization would achieve the desired outcomes regardless of social enterprises and whether there are different leadership styles appropriate for general and social enterprises.

2.3. Leadership Styles and Effects of Social Enterprise’s Leader

To understand how the leadership styles of leaders affect the performance of social enterprises, it is necessary to first consider what the effects of leadership are. This study considers ‘Calling’ as the effect of leadership in concert with the characteristics of social enterprise along with ‘Leader Trust’, one of the main effects of the leadership on an organization. Leader trust is the interpersonal trust that arises from vertical relationships within the organization, including the willingness to bear the disadvantages that can arise from trusting a leader [22]. Therefore, when members trust in a leader, it is a key factor in actively playing a role assigned to them and striving to achieve the performance goals presented by the leader [23]. Calling is one of the perceptions of an individual about his or her work, an attitude of having a positive influence on the publicness of society by realizing its role and pursuing meaning and goals within it [24]. Social enterprises are different from those already existing because the establishment or goal of the organization emphasizes sociality or public good [25]. Thus, the organization’s members’ calling concerning the direction of the social enterprise needs to be considered as an important factor in achieving performance [26].

As mentioned earlier, social enterprises are complex organizations that pursue economic and social goals simultaneously, and various skills of leadership are required in leading them [14]. Hazy and Uhl-Bien [27,28] compared and analyzed 20 studies on the leadership of complex organizations, including social enterprises, and presented five competencies for leaders of complex organizations [14]. They are as follows; First is enacting community building to recruit, select, motivate, and unify individuals. Second is structuring activities, resources, and people for efficacious decision−making and action. Third is administrating plans and programs to acquire, maintain, and defend resources. Fourth is gathering and synthesizing information for situational awareness across the ecosystem. Fifth is generating options for the future by experimentation and entrepreneurial risk taking.

Social enterprises are also currently trying to examine whether the leadership styles considered in existing leadership studies are appropriate for social enterprises. Bardmili et al. [29] and Gillet et al. [30] saw that transformational leadership is positive for motivating members of social enterprises by presenting visions. Bhutiani et al. [31] and Park [32] saw that entrepreneurship, which is not afraid of risks and is willing to challenge new ones, is the right leadership for improving the performance of social enterprises. Renko et al. [33] and Kruse et al. [34] insisted that entrepreneurship influences and directs followers towards the achievement of organizational goals that involve identifying and exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities [8]. Greenleaf [35] said that the servant leader focuses on the development of followers and stresses to them the importance of serving others, Klamon and Zurich [36] also demonstrated the importance of servant leadership. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1-1 (H1-1).

The transactional leadership of a social enterprise leader will not have a significant relationship with leader trust.

Hypothesis 1-2 (H1-2).

The transformational leadership of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with leader trust.

Hypothesis 1-3 (H1-3).

The servant leadership of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with leader trust.

Hypothesis 1-4 (H1-4).

The entrepreneurship of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with leader trust.

Hypothesis 1-5 (H1-5).

The transactional leadership of a social enterprise leader will not have a significant relationship with calling.

Hypothesis 1-6 (H1-6).

The transformational leadership of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship withcalling.

Hypothesis 1-7 (H1-7).

The servant leadership of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with calling.

Hypothesis 1-8 (H1-8).

The entrepreneurship of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with calling.

2.4. Leadership of Social Enterprise’s Leader and Organizational Effectiveness

Since social enterprises are also a form of organization, performance through business activities is important [37]. Pasricha et al. [11] believe that social enterprises are organizations that achieve social goals by engaging in commercial activities, and that social enterprises should consider leadership as an important factor in achieving their goals. Bhattarai et al. Shin [37] suggested that social enterprises can better convert their financial performance into social performance than corporations because cooperatives pay more attention to social goals than economic goals. Bhattarai et al. [38] insisted that the pursuit of certain commercial business practices such as market orientation and market disruptiveness capability improve both the economic performance and social performance of social enterprises. In other words, they emphasized that even social enterprises that value social purpose should focus on improving performance.

There is a debate on what to look at as a social enterprise’s performance. Many studies have focused on non−financial performance in the sense that the economic performance of social enterprises is insufficient. Balser and McClusky [39] defined the achievement of social enterprises as meeting the expectations of various stakeholders, and they suggested achievement of goals, securing resources, and reputation as a means of doing so. Cho and Ha [40] emphasized the importance of voluntary action in achieving social goals and viewed organizational citizenship behavior as the outcome of social enterprise. Social Firm UK [41] developed the Social Firm Performance Dashboard to identify achievements as well as to provide informative information to customers and investors by measuring the economic and social impacts of social enterprises.

Crucke and Decramer [42] argued that the evaluation of social enterprises should express both economic and social values. Kim et al. [43] analyzed the effects on commercial and public performance for corporate-connected organizations among the certified social enterprises. According to Orlizky et al. [44], Wu [45], and Molina-Azorin et al. [46], there is a positive correlation between social and environmental performance and financial performance. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2-1 (H2-1).

The transactional leadership of a social enterprise leader will not have a significant relationship with organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 2-2 (H2-2).

The transformational leadership of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 2-3 (H2-3).

The servant leadership of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 2-4 (H2-4).

The entrepreneurship of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 2-5 (H2-5).

The transactional leadership of a social enterprise leader will not have a significant relationship with economic performance.

Hypothesis 2-6 (H2-6).

The transformational leadership of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with economic performance.

Hypothesis 2-7 (H2-7).

The servant leadership of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with economic performance.

Hypothesis 2-8 (H2-8).

The entrepreneurship of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with economic performance.

Hypothesis 2-9 (H2-9).

The transactional leadership of a social enterprise leader will not have a significant relationship with social performance.

Hypothesis 2-10 (H2-10).

The transformational leadership of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with social performance.

Hypothesis 2-11 (H2-11).

The servant leadership of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with social performance.

Hypothesis 2-12 (H2-12).

The entrepreneurship of a social enterprise leader will have a positive relationship with social performance.

2.5. Mediating Effects of Leader Trust and Calling

Newman et al. [8] considered the influence of leadership on the organizational commitment and innovation behavior of employees but failed to identify which variables had a mediating effect in the process as a major limitation. They pointed out that it is important for social enterprises, like profit firms, to reveal the process by which leadership influences employees and performance. Therefore, in this study, the influence of various leadership styles on the performance of social enterprises was considered, and in the process, leader trust and sense of vocation were considered as mediating variables.

Leader trust is also considered as an outcome variable of leadership but is often considered as a mediating variable in the relationship between leadership and organizational effectiveness. Mo and Shi [47] asserted that employees may become psychologically distressed and emotionally upset when they perceive a loss of trust toward their leader. They suggested and proved the mediating effect of leader trust on the relationship between ethical leadership and employees’ deviant behaviors. Schaubroeck et al. [48] also insisted on the importance of trust between leader and members. Employees who maintain relationships based on trust in their leader often have a stronger sense of psychological identification with the organization. Arshad et al. [49] suggested that a good relationship between leader and members is an important mediator for improving the performance of social enterprises. Thus, they may have a higher motivation to exert greater effort and achieve better performance in the workplace [47].

Since interest in calling has only recently increased, research on the mediating effect of calling in the relationship between leadership and performances of social enterprises is also insufficient. However, based on a review of some papers that have verified the mediating effect of calling, it is confirmed that calling needs to be considered as a mechanism in mediating the relationship between leadership and organizational effectiveness. Chen et al. [50] examined the mediating effect of calling on the relationship between self-leadership and the perception of employment possibility. Esteves and Lopes [51] investigated calling as a mediator between the job demand and turnover intention. Cornelisson et al. [9] argued that leadership had an effect on performance only when a leader encouraged team members to recognize why they had to do their work. Through further research, they proved that the leadership of leaders influences the satisfaction of members, and the calling has mediating effects in these processes [51]. Based on these previous studies, we can surmise that calling will have a mediating effect in the relationship between leadership and organizational effectiveness even in social enterprises. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3-1 (H3-1).

Leader trust will mediate the impact of social enterprise leaders’ transformational leadership on organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 3-2 (H3-2).

Leader trust will mediate the impact of social enterprise leaders’ servant leadership on organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 3-3 (H3-3).

Leader trust will mediate the impact of social enterprise leaders’ entrepreneurship on organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 3-4 (H3-4).

Calling will mediate the impact of social enterprise leaders’ transformational leadership on organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 3-5 (H3-5).

Calling will mediate the impact of social enterprise leaders’ servant leadership on organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 3-6 (H3-6).

Calling will mediate the impact of social enterprise leaders’ entrepreneurship on organizational commitment.

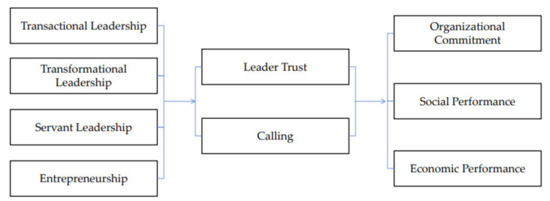

Based on the hypotheses examined above, the research model is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The research model.

3. Research Methods and Measures

3.1. Participants and Procedures

This study aimed to investigate how various leadership styles exerted to their members by the leaders of social enterprises can improve organizational effectiveness, thereby verifying what style of leadership is best suited to achieving the purpose of establishment and corporate objective of social enterprises. In consideration of the purpose of this study, only those employees working on companies certified as social enterprises by the Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency were included as participants of this study. By the end of 2020, a total of 2747 companies were certified as social enterprises. Among them, 318 social enterprises in Seoul were sent an e-mail explaining the purpose of this study. The survey was then conducted for members of 42 social enterprises who were willing to take the survey. A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed. Those with incomplete answers, such as missing questions or one-way responses, were excluded regardless of the questions. Finally, 251 questionnaires (83.7% response rate) were used for analysis.

Table 3 reports characteristics of samples, demographic variables, information of firm and industries.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Samples (N = 251).

3.2. Measures

For all measures, participants rated items using a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 = ‘strongly agree’.

3.2.1. Transactional Leadership

Based on the research of Bass and Avolio [52], transactional leadership was defined as understanding as the process of providing the desired performance of the leader by presenting the situational reward to the subordinate based on the exchange relationship between the leader and subordinates. The 3-item questionnaire (MLQ-5X) developed by Bass and Avolio [52] was used to measure the supervisor’s transactional leadership. Sample items included ‘My supervisor is interested in specifics about who is responsible for achieving performance goals’ and ‘My supervisor articulates the rewards for achieving the performance goals’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.712.

3.2.2. Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership was defined based on the research of Bass and Avolio [52] as a style of leadership that presents a vision and induces changes in values to members through charisma, individual consideration, and intellectual stimulation to promote higher achievement. The 5-item questionnaire (MLQ-5X) developed by Bass and Avolio [52] was used to measure the supervisor’s transformational leadership. Sample items included ‘My supervisor treats me as an individual rather than as a member of the organization’ and ‘My supervisor helps me to see the problem from various perspectives’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.845.

3.2.3. Servant Leadership

Servant leadership was defined, referring to Ehrhart [53], as a style of leadership that prioritizes organizational members, customers, and communities to serve others, and is dedicated to satisfying their needs. The 6-item questionnaire (MLQ-5X) developed by Newman et al. [8] was used to measure the supervisor’s servant leadership. Sample items included ‘My supervisor creates a sense of community among employees’ and ‘My supervisor makes the personal development of employees a priority’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.900.

3.2.4. Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship was defined by Helm and Andersson [54] as the behavior that triggers or generates the interaction of innovation, initiative, and risk taking. The 9−item questionnaire developed by Helm and Andersson [54] was used to measure the supervisor’s entrepreneurship. Sample items included ‘My supervisor often offers innovative improvements for products/services’ and ‘My supervisor encourages me to practice in a more innovative way’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.909.

3.2.5. Leader Trust

Leader trust was defined by Dirks [55] as the willingness of members to rely on the leader’s behavior in situations where opportunistic behavior of the leader is possible. The 6-item questionnaire developed by Conger et al. [56] was used to measure the follower’s trust in the supervisor. Sample items included ‘I have full faith in the integrity of my supervisor’ and ‘I will trust and support my supervisor in any emergency’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.896.

3.2.6. Calling

Calling was defined as an attitude to realize one’s role in work, pursue meaning and goals in it, and thereby have a positive effect on the publicity of society [57]. The 5-item questionnaire developed by Bunderson and Thompson [57] was used to measure the follower’s calling. Sample items included ‘This job feels like a place I must keep in my life’ and ‘I was born with the destiny of being dedicated to this job’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.865.

3.2.7. Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment was defined as an employee’s emotional attachment to and identification with the organization [58]. The 4-item questionnaire developed by Newman et al. [8] was used to measure the follower’s organizational commitment. Sample items include ‘I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career at this organization’ and ‘I am proud to tell others that I am part of the organization’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.898.

3.2.8. Economic Performance

Economic performance was defined as financial performance and management independence to maintain and develop social enterprises [38]. The 4-item questionnaire developed by Bhattarai et al. [32] was used to measure the follower’s organizational commitment. Four items developed based on Bhattarai et al. [38] were used to measure the perceived economic performance of followers. Sample items include ‘I think the firm has generated a high volume of sales’ and ‘The performance of this firm has been very satisfactory’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.863.

3.2.9. Social Performance

Social performance was defined as the degree to which social enterprises ultimately seek to achieve values and social contribution [38]. The 5-item questionnaire based on results of Bhattarai et al. [38] was used to measure the perceived social performance of followers. Sample items include ‘The firm contributes to the stabilization of society’ and ‘The firm is welcomed by locals’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.769.

3.2.10. Control Variables

We followed past research to control for the effects of participants’ position at the social enterprise (code 0 = staff, 1 = team leader/section chief, 2 = director/head of department, 3 = CEO), tenure (code 0 = less than 1 year, 1 = 1~5 years, 2 = 6~10 years, 3 = 11 years or more), experience as the supervisor (coded 0 = have not, 1 = have), number of employees as a firm size (code 0 = less than 5, 1 = 5~10, 2 = 11~20, 3 = 21 or more), firm type (code 0= for-profit 1 = non-profit, 2 = co-op, 3 = others) and industry (code 0 = manufacturing, 1 = service, 2 = others) were also included as control variables because past leadership research reported that such control variables are consistently related to followers’ perceptions of social enterprises’ leadership or performances. Finally we controlled the effects of participants’ gender (code 0 = man, 1 = woman, 2 = others), age (code 0 = 20~29 years old, 1 = 30~39, 2 = 40~49 3 = 50 years or older) and educational background (code 0 = high school graduate, 1 = bachelor’s degree, 2 = master’s degree, 3 = doctorate) as demographical variables in order to ensure that they did not confound the direct effects of social enterprise’ leaderships or performances.

3.3. Data Analysis

Before hypothesis testing was undertaken, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using SPSS 21 to determine the construct validity of study variables. The data collected in this study verified the reliability and validity of the measurement tool through the measurement validation process suggested by Nunnally [59]. Purification process and unidimensional verification were performed on 47 items used to measure a total of 9 variables, and reliability was tested through Cronbach’s alpha value. No anomalous results were found in the process. Principal component factor analysis was used to verify the validity, and Varimax rotation was performed to maintain mutual independence between factors as a factor rotation method. The items were grouped significantly by the variable to be measured, and the eigen value also exceeded 1 (transactional leadership = 1.013, transformational leadership = 1.393, servant leadership = 1.539, entrepreneurship = 10.959, leader trust = 8.624, calling = 2.884, organizational commitment = 2.147, economic performance = 1.614, social performance = 1.252). All variables were grouped into one variable without loss of questionnaire items, and future analysis was performed based on these results.

4. Results

4.1. Correlation Analysis

Table 4 shows the means, standard deviations, and Spearman correlations of the study constructs. Means and standard deviations of the constructs ranged from 3.296 to 3.791 and 0.689 to 0.878, respectively. Regarding the correlations between the constructs, the correlation coefficients revealed that all chosen constructs are distinct, and the highest correlation exists between entrepreneurship and servant leadership (r = 0.731, p < 0.01).

Table 4.

Correlation matrix and descriptive statistics.

4.2. Regression Analysis

Regression analysis that it is a two-tailed test was performed to verify the hypothesis, and the results were presented in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. Table 5 is an analysis result that tested hypotheses 1 and 2, and transactional leadership did not show a significant relationship with leader trust (β = 0.019, n.s.) and calling (β = 0.094, n.s.). The independent variables that showed a significant relationship with leader trust were transformational leadership (β = 0.304, p < 0.001), servant leadership (β = 0.231, p < 0.01), and entrepreneurship (β = 0.342, p < 0.001). The independent variable that showed a significant positive relationship with calling was transformational leadership (β = 0.257, p < 0.01). Therefore, hypotheses 1-1, 1-2, 1-3, 1-4, 1-5, and 1-6 were accepted, and hypotheses 1-7 and 1-8 were rejected.

Table 5.

Factors affecting leader trust and calling.

Table 6.

Mediating effects of leader trust.

Table 7.

Mediating effects of calling.

Hypothesis 2 is a hypothesis concerning the leadership exercised by leaders of social enterprises and their performance, and the results of this analysis were confirmed through Models 1, 3, and 5 in Table 6 (or Table 7). First, the leadership styles that showed a significant positive relationship with organizational commitment were transformational leadership (β = 0.132, p < 0.1), servant leadership (β = 0.231, p < 0.01), and entrepreneurship (β = 0.306, p < 0.001). Transactional leadership (β = 0.041, n.s.) did not show a significant relationship as expected in the hypothesis (the Model 1 of Table 6). Therefore, hypotheses 2-1, 2-2, 2-3, and 2-4 related to organizational commitment were all accepted.

Next, as expected through the hypothesis, the leadership styles that showed a significant positive relationship with economic performance were transformational leadership (β = 0.187, p < 0.1) and entrepreneurship (β = 0.282, p < 0.01). However, contrary to the prediction of the hypothesis, transactional leadership (β = 0.170, p < 0.05) showed a significant positive relationship, and servant leadership (β = −0.176, p < 0.1) showed a significant negative relationship. Therefore, hypotheses 2-6 and 2-8 were accepted, and hypotheses 2-5 and 2-7 were rejected.

Finally, as expected through the hypothesis, the leadership style that showed a significant positive relationship with social performance was entrepreneurship (β = 0.286, p < 0.01). Transactional leadership (β = 0.079, n.s.) also did not show a significant relationship with social performance as expected. Therefore, hypotheses 2-9 and 2-12 were accepted, and hypotheses 2-10 and 2-11 were rejected.

Hypothesis validation on the mediating effect of leader trust was confirmed through Table 5 and Table 6. First, looking at Table 5, the independent variables that had a significant effect on leader trust were transformational leadership, servant leadership, and entrepreneurship.

Next, Models 1 and 2 in Table 6 showed the mediating effect of leader trust on the relationship between leadership style and organizational commitment of social enterprises. As leader trust was added to four independent variables, the explanatory power of Model 1 was improved. Before leader trust was introduced, three variables except transactional leadership had a significant relationship with organizational commitment. However, when leader trust was included, transformational leadership failed to show a significant relationship, and servant leadership and entrepreneurship maintained a significant relationship. Therefore, it was confirmed that leader trust fully or partially mediates the effects of social enterprise leadership styles on organizational commitment, except for in the case of transactional leadership, and the related hypothesis 3-1 was adopted.

Models 3 and 4 in Table 6 showed the mediating effect of leader trust on the relationship between leadership style and economic performance of social enterprises. When leader trust was added to the four independent variables, the explanatory power of Model 3 improved. All leadership styles had a significant relationship with economic performance before leader trust was included, but when leader trust was inserted, transformational leadership did not show a significant relationship, and the remaining three styles maintained a significant relationship. Therefore, it was confirmed that leader trust fully or partially mediates the effects of social enterprise leadership styles on economic performance, and hypothesis 3-2 was also adopted.

Models 5 and 6 of Table 6 showed the mediating effect of leader trust on the relationship between leadership style and social performance of social enterprises. As leader trust was added to the four independent variables, the value of Adj.R2 of Model 6 was rather reduced, and the conditions for mediating effect validation were not satisfied. In addition, as in Model 6, leader trust did not secure significance with social performance. Therefore, leader trust could not test whether leadership styles of social enterprises mediate the effect on social performance, and hypothesis 3-3 was rejected.

Hypothesis validation on the mediating effect of calling was confirmed through Model 4 of Table 5 and Table 7. First, in Table 5, the only independent variable that had a significant relationship with calling was transformational leadership. Therefore, the mediating effect of calling was analyzed only for transformational leadership. Table 7 shows the mediating effect of calling on the relationship between the leadership style of social enterprises and the three outcomes. Among Models 2, 4, and 6, where calling was added to the four independent variables, Model 2 showed improved explanatory power. The mediating effect of calling in transformational leadership’s impact on economic and social performance was not confirmed. Therefore, Hypothesis 3-5 and Hypothesis 3-6 were rejected. In Models 1 and 2 of Table 7, transformational leadership had a significant relationship with organizational commitment before calling into statistics, but the relationship between two variables was insignificant when calling was considered as a variable. Therefore, calling fully mediated the effect of transformational leadership on organizational commitment, and Hypothesis 3-4 was partially accepted.

5. Discussion

As the importance of social enterprises is emphasized, many researchers are studying ways to improve performance. Some researchers are concerned with the leadership style, which is important in profit firms to social enterprises, but they do not consider the characteristics of social enterprises. Social enterprises are hybrid organizations that maintain both social welfare logic and commercial logic [5,7,8]. However, social enterprises offer the promise of financially sustainable organizations that respond to the world’s greatest problems [38]. Therefore, it may sound reasonable to apply the leadership style used by profit firms to social enterprises. Some studies, such as Smith et al. [4], claim that the leadership used by commercial companies is also suitable for social enterprises. However, there is a lack of research on what constitutes effective leadership in social enterprises given their unique mix of social and commercial objectives [8]. In particular, start-ups of social enterprises in Korea are largely driven by the government to support the socially disadvantaged. Thus, social enterprises in Korea tend to prioritize securing government support rather than voluntary efforts for their success. Recently, the financial independence of social enterprises has been emphasized as an important success criterion in Korea. Therefore, interest in leadership as the key of improving performance is increasing in Korean social enterprises.

This study focused on the relationship between four styles of leadership and organizational effectiveness with the mediating effect of leader trust and calling. The results of this study founded that it is necessary to be wary of applying the leadership of for−profit enterprises directly to social enterprises and expecting full effects. In other words, this study showed that leadership style, which contributes to performance improvement in for−profit firms, can have different impacts on performance in social enterprises. Transactional leadership only showed an effect on economic performance and did not show significance with other variables. This was the same result as the studies on for−profit companies that showed the limited effect of transactional leadership [27,28]. It was confirmed that transformational leadership is a mechanism improving various variables considered as performance of social enterprises, and as the mediating effect of leader trust and calling was also verified, it also helped to understand the effect of transformational leadership on the performance of social enterprises. Therefore, it was confirmed that transformational leadership is a major leadership style that helps improve performance regardless of whether a company is for-profit or considers both for-profit and non-profit goals.

The claim that servant leadership and entrepreneurship will help improve performance in the studies on for-profit enterprises was also supported in this study on social enterprises. Newman et al. [8] suggested that entrepreneurship would improve organizational commitment in social enterprises by presenting many theoretical arguments, but empirical analysis failed to verify this. However, in this study, entrepreneurship was confirmed to have a significant relationship with all performance variables except for calling, also confirming that it was an important leadership in improving performance of social enterprises.

On the other hand, it was also confirmed that the results were different from results expected based on previous studies. It was confirmed that only entrepreneurship had an impact on social performance improvement, one of the main objectives of social enterprises, and that servant leadership could have a negative effect on the economic performance of social enterprises. This is contrary to the argument of Pasricha et al. [11]. They argued that the role of each member of a social enterprise had a significant impact on performance, and ethical leaders perform better social responsibility by instilling ethical awareness among members. Therefore, according to their argument, servant leadership that focuses on individual members rather than leaders should be more helpful in improving social performance. However, in this study, entrepreneurship that inspires a sense of challenge helped social performance, and servant leadership reduced economic performance. This can be fully explained by looking at the study of Gibbons and Hazy [14]. They showed that it is important to demonstrate an organizational culture and leadership that can willingly support the economic performance created through for−profit activities in activities to create social value. In other words, the creation of economic value through the exercise of a challenging spirit can have an important effect on the expression of social value, and leadership that supports the activities of individuals focusing on social values can cause a sacrifice of economic performance. Therefore, rather than showing results contrary to the claims of previous studies, it can be seen that the relationship between leadership and performance of social enterprises needs to be analyzed more in-depth, and as Smith et al. [4] argues, it may be interpreted as due to the complexity of social enterprises itself.

This study has several limitations and one such limitation is that it did not measure actual performance, but perceived performance. Although economic performance was measurable, it could not be used due to difficulty in controlling other variables affecting financial performance. In future research, supplementation with archival data on social enterprises will be necessary. Next, this study measured all four leadership styles perceived by employees of a leader of a social enterprise, but the leadership exercised by the leader is highly likely to be of a single style. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the leadership of social enterprise leaders, classify it as one of the four styles, and conceive a method to study their performance and relevance. Future research will also need to pay attention to what leadership is suitable for the characteristics of social enterprises. For example, it will be necessary to study whether spiritual leadership that can inspire calling is suitable for social enterprises. Data for this study were collected at the same point in time and sources, and this may cause causal ambiguity in the results. Despite these shortcomings, we consider this study to be meaningful in that it contributed to the efforts of objectively finding a leadership style suitable for social enterprises.

6. Conclusions

This study’s focus was that social enterprise considers both economic and social values. In other words, this study aimed to see the effects of major leadership styles (transactional leadership, transformational leadership, servant leadership, and entrepreneurship) that have been in the spotlight on social enterprise performance. More specifically, the social enterprise performance considered organizational commitment, perceived economic performance, and social performance. Leadership trust and calling were considered as mediating parameters in the relationship between leadership styles and performances.

Using data from 251 employees in 42 social enterprises in Seoul, the leader trust and organizational commitment have positive relationships with transformational leadership, servant leadership, and entrepreneurship. Calling only has a positive relationship with transformational leadership and social performance has a positive relationship with entrepreneurship. The economic performance has positive relationships with transactional leadership, transformational leadership and entrepreneurship. However, economic performance shows a unique pattern, as a negative relationship with the servant leadership, and leader trust and calling have mediating effects on the relationship between transformational leadership and organizational commitment, transformational leadership, and economic performance. This study confirmed that leadership trust and calling mediate the impact of transformational leadership on performance.

These findings represent an important step forward in elucidating what leadership is appropriate for social enterprises. It was confirmed that transformational leadership can be an effective leadership for performance improvement even if a company pursues social goals, and it has been shown that leader trust and calling can be mediated in the process. In addition, it was confirmed that entrepreneurship, a leadership that emphasizes the spirit of challenge, can also contribute to improving social performance, and that transactional leadership was empirically found to be only involved in improving economic performance.

Author Contributions

S.C.: Conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft; M.J.: methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tracey, P.; Phillips, N. The distinctive challenge of educating social entrepreneurs: A postscript and rejoinder to the special issue on entrepreneurship education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Edu. 2007, 6, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J.; Gabrielsson, J. Public policy for social innovations and social enterprise—What’s the problem represented to be? Sustainablity 2021, 13, 7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Besharov, M.L. Bowing before dual gods: How structured flexibility sustains organizational hybridity. Admin. Sci. Q. 2019, 64, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Besharov, M.L.; Wessels, A.K.; Chertok, M. A paradoxical leadership model for social entrepreneurs: Challenges, leadership skills, and pedagogical tools for managing social and commercial demands. Acad. Manag. Learn. Edu. 2012, 11, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.C.; Santos, F. Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ko, W.W.; Liu, G. The transformation from traditional nonprofit organziations to social enterprise: An insitutional entrepreneurship perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vázquez−Maguirre, M. Building sustainable rural communities through indigenous social enterprises: A humanistic approach. Sustainablity 2021, 12, 9643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Neesham, C.; Manville, G.; Tse, H.H. Examining the influence of servant and entrepreneurial leadership on the work outcomes of employees in social enterprises. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2905–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J.P.; Akemu, O.; Jonkman, J.G.F.; Werner, M.D. Building character: The formation of a hybrid organizational identity in a social enterprise. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1294–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Post, J.E. Social entrepreneurs and catalytic change. Publ. Admin. Rev. 1991, 51, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasricha, P.; Singh, B.; Verma, P. Ethical leadership, organic organizational cultures and corporate social responsibility: An empirical study in social enterprises. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C.; Solari, L. Management challenges. In The Emergence of Social Enterprise; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 333–349. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.; Leonard, H.; Reficco, E.; Wei−Skillern, J. Social entrepreneurship: It is for corporation, too. In Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, J.; Hazy, J.K. Leading a large−scale distributed social enterprise: How the leadership culture at goodwill industries creates and distributes value in communities. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2017, 27, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). Social Enterprise: A Strategy for Success; DTI: London, UK, 2002. Available online: https://www.dti.gov.uk/socialenterprise/strategy.htm (accessed on 6 June 2005).

- Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency (KSEPA). Type of Social Enterprise; KSEPA: Gyeonggi-do, Korea, 2013; Available online: https://www.socialenterprise.or.kr/social/ente/concept.do?m_cd=E001 (accessed on 19 March 2013).

- Borzaga, C.; Defourny, J. From Third Sector to Social Enterprise; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Social Enterprise Coalition. There’s More to Business Than You Think: A Guide to Social Enterprise; Social Enterprise Coalition: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, J.G.; Emerson, J.; Economy, P. The social enterprise spectrum. In Enterprising Nonprofits: A Toolkit for Social Entrepreneur; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, Y. A study on the leadership of social enterprise. Korean NPO Rev. 2012, 11, 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, D. An exploratory study on leadership of social economy organization. J. Korean Soc. Welf. Admin. 2013, 15, 285–311. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, M. The effect of leaders emotional intelligence and leader trust on team effectiveness. Korea J. Bus. Admin. 2009, 22, 2895–2918. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.Y.; Oh, H.S.; Chung, M.H. The effects of the social relationship and network characteristics on trust in leaders. Korean J. Manag. 2016, 24, 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dike, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Calling and vocation at work definitions and prospects forresearch and practice. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 37, 424–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauanui, S.K.; Thomas, K.D.; Rubens, A.; Sherman, C.L. Entrepreneurship and spirituality: A comparative analysis of entrepreneurs’ motivation. J. Small Bus. Entrepr. 2010, 23, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, K.M. The effect of social enterprise workers’ sense of the calling and working environment on turnover intention: Mediating effects of job satisfaction and job engagement. Korean Manag. Consult. Rev. 2018, 18, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hazy, J.K.; Uhl−Bien, M. Changing the rules: The implications of complexity science for leadership research and practice. In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 711–732. [Google Scholar]

- Hazy, J.K.; Uhl−Bien, M. Towards operationalizing complexity leadership: How generative, administrative and community−building leadership enact organizational outcomes. Leadership 2015, 11, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bardmili, S.H.; Siadat, S.A.; Mohammadisadr, M. The study of relation between spiritual leadership of principals and quality of work life of teachers in high schools of city of Izeh. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2013, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gillet, N.; Fouquereau, E.; Bonnaud−Antignac, A.; Mokounkolo, R.; Colombat, P. The mediating role of organizational justice in the relationship between transformational leadership and nurses’ quality of work life: A cross−sectional questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutiani, D.; Flicker, K.; Nair, P.; Groen, A. Is social entrepreneurship transformational leadership in action. In The Patterns in Social Entrepreneurship Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 110–134. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.H.; Kim, H.Y. The effects of transforming leadership of social entrepreneurs on business strategies and organizational effectiveness in Korea. J. Northeast Asian Stud. 2014, 72, 377–398. [Google Scholar]

- Renko, M.; El Tarabishy, A.; Carsrud, A.L.; Brannback, M. Understanding and measuring entrepreneurial leadership style. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, P.; Wach, D.; Wegge, J. What motivates social entrepreneurs? A meta−analysis on predictors of the intention to found a social enterprise. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 59, 477–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R.K. Servant Leadership: A Journey Into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness; Paulist Press: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Klamon, V.; Zurich, S. In the name of service: Exploring the social enterprise workplace experience through the lens of servant leadership. Int. J. Servant Leadersh. 2007, 3, 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y. When does financial performance of social enterprise translate to social performance? In Proceedings of the Academy of Management 81th Annual Meeting, Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 26 July 2021–4 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, C.R.; Kwong, C.C.; Tasavori, M. Market orientation, market disruptiveness capability and social enterprise performance: An empirical study from the United Kingdom. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balser, D.; McClusky, J. Managing stakeholder relationships and nonprofit organization effectiveness. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2005, 15, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, Y.B.; Ha, T.Y. A study on effect of workplace spirituality of community enterprise on organizational citizenship behavior: Mediating effects of job satisfaction. Manag. Inf. Syst. Rev. 2016, 35, 137–165. [Google Scholar]

- Social Firms UK. The Social Firm Performance Dashboard; Social Firm: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Crucke, S.; Decramer, A. The development of a measurement instrument for the organizational performance of social enterprises. Sustainability 2016, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kwon, H.Y.; Han, Y.O. The study on the success factors of corporate associated social enterprise. Korean NPO Rev. 2010, 8, 39–65. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta−analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.L. Corporate social performance, corporate financial performance, and firm size: A meta−analysis. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2006, 8, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Molina−Azorín, J.F.; Claver−Cortés, E.; Pereira−Moliner, J.; Tarí, J.J. Environmental practices and firm performance: An empirical analysis in the Spanish hotel industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.; Shi, J. Linking ethical leadership to employee burnout, workplace deviance and performance: Testing the mediating roles of trust in leader and surface acting. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.M.; Peng, A.C.; Hannah, S.T. Developing trust with peers and leaders: Impacts on organizational identification and performance during entry. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1148–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Abid, G.; Torres, F.V.C. Impact of prosocial motivation and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of ethical leadership and leader−member exchange. Qual. Quant. 2021, 55, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lee, A.Y.; Ahlstrom, D. Strategic talent management systems and employee behaviors: The mediating effect of calling. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2021, 59, 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, T.; Lopes, M.P. Crafting a calling: The mediating role of calling between challenging job demands and turnover intention. J. Career Dev. 2017, 44, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire; Mind Garden: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart, M.G. Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit−level organizational citizenship behavior. Pers. Psychol. 2004, 57, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.T.; Andersson, F.O. Beyond taxonomy: An empirical validation of social entrepreneurship in the nonprofit sector. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2010, 20, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, K.T. Trust in leadership and team performance: Evidence from NCAA basketball. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Conger, J.A.; Kanungo, R.N.; Menon, S.T. Charismatic leadership and follower effects. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2000, 21, 747–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunderson, J.S.; Thompson, J.A. The call of the wild: Zookeepers, callings, and the double−edged sword of deeply meaningful work. Admin. Sci. Q. 2009, 54, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three−component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw−Hill: NewYork, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).