Characteristics of Social Media Content and Their Effects on Restaurant Patrons

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Marketing Communication Process and Attitude

2.2. Social Influence and Conformity

2.3. Characteristics of Social Media Message Content

2.3.1. Authenticity

2.3.2. Consensus

2.3.3. Usefulness

2.3.4. Aesthetics

3. Hypotheses

3.1. The Impact of Social Media Content Characteristics on Attitude toward the Message

3.2. The Influence of Attitude toward the Message on Brand Attitude and Behavioral Intentions

3.3. The Influence of Brand Attitude on Behavioral Intentions

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

4.2. Measures

5. Result

5.1. Demographic Profile

5.2. The Measurement Model

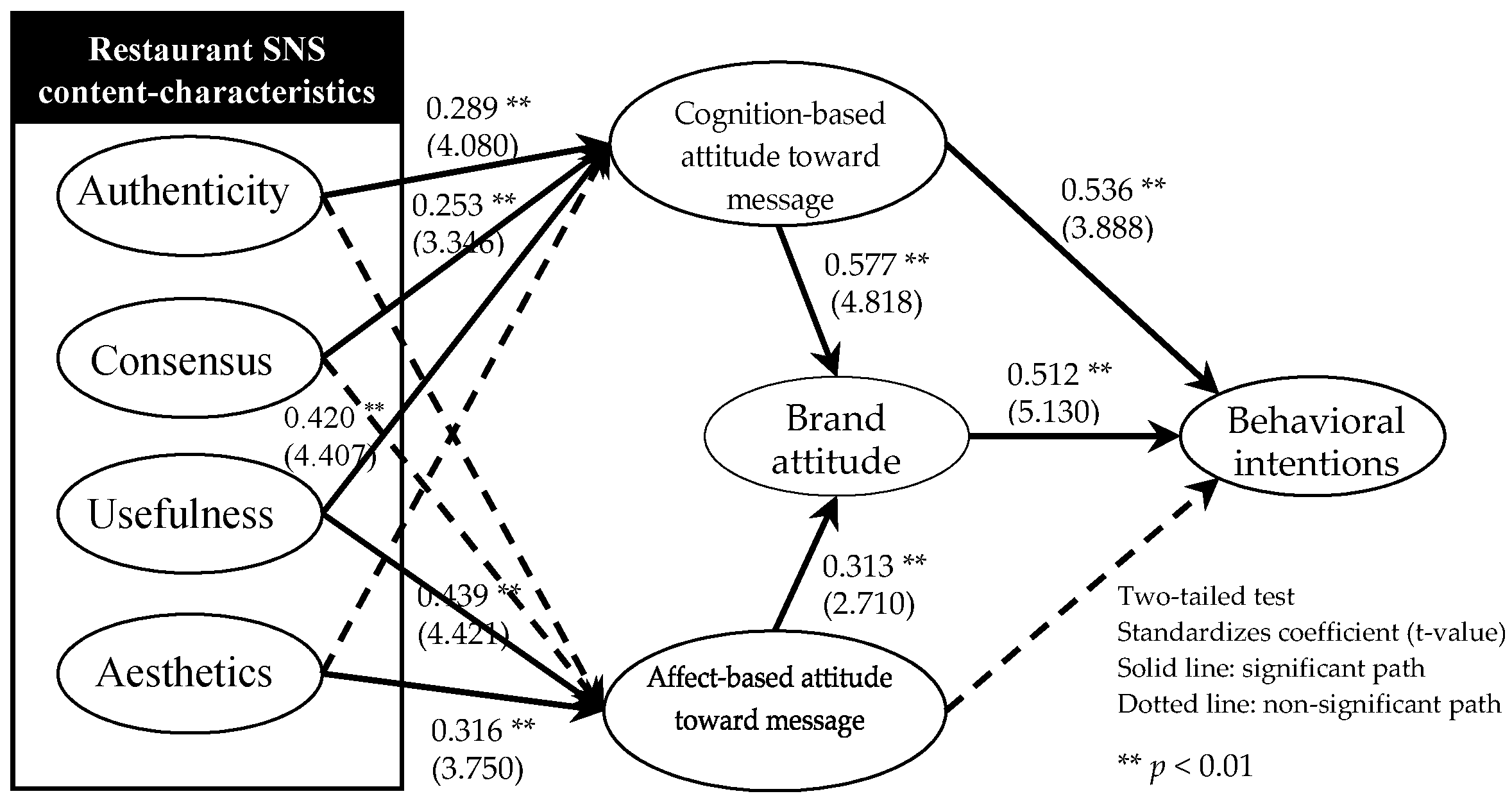

5.3. The Structural Model and Testing of the Hypotheses

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whiting, A.; Deshpande, A. Towards greater understanding of social media marketing: A review. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2016, 18, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bei, L.T.; Chen, E.Y.I.; Rha, J.Y.; Widdows, R. Consumers’ online information search for a new restaurant for dining-out: A comparison of US and Taiwan consumers. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2003, 6, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, W. Content strategies and audience response on Facebook brand pages. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 927–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Li, J.; Brymer, R.A. The impact of social media reviews on restaurant performance: The moderating role of excellence certificate. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.D.; Beatty, S.E.; Dalela, V.; Morgan, R.M. A generalized multidimensional scale for measuring customer engagement. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2014, 22, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R.G. Influence of social media marketing communications on young consumers’ attitudes. Young Consum. 2017, 18, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesly: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, H.C. Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. J. Confl. Resolut. 1958, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedicktus, R.L.; Brady, M.K.; Darke, P.R.; Voorhees, C.M. Conveying trustworthiness to online consumers: Reactions to consensus, physical store presence, brand familiarity, and generalized suspicion. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S.Y.; Chung, N.; Ahn, K.; Lee, J.W. When social media met commerce: A model of perceived customer value in group-buying. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Hong, S.; Lou, H. Beautiful beyond useful? The role of web aesthetics. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2010, 50, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.; Amir, O.; Ariely, D. In search of homo economicus: Cognitive noise and the role of emotion in preference consistency. J. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.D.; Woo, C.; Singh, A.J. Elaboration likelihood model: A missing intrinsic emotional implication. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2005, 14, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M.W.; Keelan, J.P.R.; Fehr, B.; Enns, V.; Koh-Rangarajoo, E. Social-cognitive conceptualization of attachment working models: Availability and accessibility effects. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.; MacInnis, D.J.; Park, C.W. The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.O.; Shi, N.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Lim, K.H.; Sia, C.L. Consumer’s decision to shop online: The moderating role of positive informational social influence. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Effectiveness of consensus information in advertising: The moderating roles of situational factors and individual differences. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MISQ 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ray, M.L. Affective responses mediating acceptance of advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.; Stayman, D.M. Antecedents and consequences of attitude toward the ad: A meta-analysis. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, C.M.; Pounders, K.R. Transforming celebrities through social media: The role of authenticity and emotional attachment. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A.; Olson, J.C. Are product attribute beliefs the only mediator of advertising effects on brand attitude? J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, B.L.; Resnik, A.J. Information content in television advertising: A replication and extension. J. Advert. Res. 1991, 31, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, M.G.; Spotts, H.E. A situational view of information content in TV advertising in the US and UK. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Ostrom, T.M.; Brock, T.C. Historical foundations of the cognitive response approach to attitudes and persuasion. In Cognitive Responses in Persuasion; Hillsdale College: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P. Message-evoked thoughts: Persuasion research using thought verbalizations. J. Consum. Res. 1980, 7, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Holbrook, M.B.; Stephens, D. The formation of affective judgments: The cognitive-affective model versus the independence hypothesis. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Burke, M.C.; Edell, J.A. The impact of feelings on ad-based affect and cognition. J. Mark. Res. 1989, 26, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakratsas, D.; Ambler, T. How advertising works: What do we really know? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.L.; Rapp, A.; Meyer, T.; Mullins, R. The role of brand communications on front line service employee beliefs, behaviors, and performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 42, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascu, D.N.; Zinkhan, G. Consumer conformity: Review and applications for marketing theory and practice. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1999, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitan, S.; Silvera, D.H. From digital media influencers to celebrity endorsers: Attributions drive endorser effectiveness. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M.; Gerard, H.B. A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1955, 51, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beverland, M. Brand management and the challenge of authenticity. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 460–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Kozinets, R.V.; Sherry, J.F., Jr. Teaching old brands new tricks: Retro branding and the revival of brand meaning. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of Information Technology. MISQ 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.W.; Park, M.C.; Lee, E. A framework for mobile SNS advertising effectiveness: User perceptions and behaviour perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2014, 33, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Liang, H.; Xue, Y. Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: A principal-agent perspective. MISQ 2007, 31, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A. In search of authenticity. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 1083–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Minor, M.S.; Wei, J. Aesthetics and the online shopping environment: Understanding consumer responses. J. Retail. 2011, 87, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.W.; Namkung, Y. Restaurant information sharing on social networking sites: Do network externalities matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 739–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A.; De Kerviler, G.; Moulard, J.G. Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M.B.; Lindgreen, A.; Vink, M.W. Projecting authenticity through advertising: Consumer judgments of advertisers’ claims. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Defining authenticity and its determinants: Toward an authenticity flow model. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class; Schocken Books: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.K.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S. To be true or not to be true: Authentic leadership and its effect on travel agents. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jang, S. Determinants of authentic experiences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2247–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Yang, Y. The effect of authenticity and social distance on CSR activity. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Han, S.H. Effects of SNS users’ perception of authenticity on acceptance and dissemination of onine e-WOM: With emphasis on media engagement as intermediating variables. Korean J. Advert. 2014, 25, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, L.; Trepte, S. Authenticity and well-being on social network sites: A two-wave longitudinal study on the effects of online authenticity and the positivity bias in SNS communication. Comput. Hum. Behavr. 2014, 30, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, G.A.; Strutton, D. Comparing email and SNS users: Investigating e-servicescape, customer reviews, trust, loyalty and E-WOM. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, D.M. Systematic and nonsystematic processing of majority and minority persuasive communications. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, S.; Lane, D.S.; Hart, P.S. In consensus we trust? Persuasive effects of scientific consensus communication. Public Underst. Sci. 2018, 27, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaker, J.L.; Maheswaran, D. The effect of cultural orientation on persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 1997, 24, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Gardikiotis, A.; Hewstone, M. Levels of consensus and majority and minority influence. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 645–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, L.; Peng, X.; Dong, Y.; Barnes, S.J. Understanding Chinese users’ continuance intention toward online social networks: An integrative theoretical model. Electron. Mark. 2014, 24, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, H. Factors influencing the usage of websites: The case of a generic portal in the Netherlands. Inf. Manag. 2003, 40, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.C. How social network characteristics affect users’ trust and purchase intention. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, L.; Yu, B. Spreading social media messages on Facebook: An analysis of restaurant business-to-consumer communications. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, T.; Tractinsky, N. Assessing dimensions of perceived visual aesthetics of web sites. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2004, 60, 269–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.Y. Effects of visual servicescape aesthetics comprehension and appreciation on consumer experience. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 692–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, J.B.; Shim, S.; Barber, B.; O’Brien, M. Adolescents’ utilitarian and hedonic Web consumption behavior: Hierarchical influence of personal values and innovativeness. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 813–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Leblanc, G. Contact personnel, physical environment and the perceived corporate image of intangible services by new clients. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2002, 13, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, C.A.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Expanding the functional information search model. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 551–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Petty, R.E. Persuasiveness of communications is affected by exposure frequency and message quality: A theoretical and empirical analysis of persisting attitude change. Current Issues Res. Advert. 1980, 3, 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bezes, C. Identifying central and peripheral dimensions of store and website image: Applying the elaboration likelihood model to multichannel retailing. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2015, 31, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shrum, L.J. A dual-process model of interactivity effects. J. Advert. 2009, 38, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, K.R.; Lee, M.S.; Sauer, P.L. The combined influence hypothesis: Central and peripheral antecedents of attitude toward the ad. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.K.; Byun, G.I.; Kim, K.J. A study on the effect of characteristics of SNS WOM information for restaurant businesses on the acceptance of WOM information and consumer attitude: Focusing on married women in Busan area. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2014, 10, 165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, S.H. The impact of a mega event on visitors’ attitude toward hosting destination: Using trust transfer theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A. Does brand loyalty mediate brand equity outcomes? J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1999, 7, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Lee, K.Y. Measuring SNS authenticity and its components by developing measurement scale of SNS authenticity. Korean J. Advert. 2013, 24, 157–179. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, M.Y.; Hwang, Y. Predicting the use of web-based information systems: Self-efficacy, enjoyment, learning goal orientation, and the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzou, R.C.; Lu, H.P. Exploring the emotional, aesthetic, and ergonomic facets of innovative product on fashion technology acceptance model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2009, 28, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Yoon, Y.S.; Park, N.H. Structural effects of cognitive and affective responses to web advertisements, website and brand attitudes, and purchase intentions: The case of casual-dining restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Lim, J.H. Measuring the consumption-related emotion construct, Korean Mark. Review 2002, 17, 55–91. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A.; Keller, K.L. Consumer evaluations of brand extensions. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Lutz, R.J. An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmider, E.; Ziegler, M.; Danay, E.; Beyer, L.; Bühner, M. Is it really robust? Reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal distribution assumption. Eur. J. Res. Meth. Behav. Soc. Sci. 2010, 6, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hul, M.K.; Dube, L.; Chebat, J.C. The impact of music on consumers’ reactions to waiting for services. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs and Items | Standardized Factor Loadings | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authenticity (CCR 1 = 0.849, AVE 2 = 0.533) | |||

| The SNS restaurant content I’ve searched for or viewed is largely credible. | 0.872 | −0.291 | 0.289 |

| I thought that the SNS restaurant content I searched for or viewed was trustworthy. | 0.918 | −0.283 | 0.008 |

| The SNS restaurant content I’ve searched for or viewed is constant. | 0.797 | −0.110 | 0.341 |

| The SNS restaurant content I’ve searched for or viewed is pure. | 0.766 | −0.148 | 0.219 |

| The SNS restaurant content I have searched for or viewed is non-commercial. | 0.636 | −0.051 | 0.455 |

| Consensus (CCR = 0.798, AVE = 0.570) | |||

| The number of SNS restaurant content that I searched for or saw was large. | 0.717 | −0.440 | 0.908 |

| The SNS restaurant content I searched for or saw was positive. | 0.676 | −0.339 | 1.248 |

| Many people agreed with the SNS restaurant content I searched for or viewed. | 0.792 | −0.224 | 1.135 |

| Usefulness (CCR = 0.814, AVE = 0.594) | |||

| The SNS restaurant content that I have searched for or seen is useful in everyday life. | 0.806 | −0.253 | 0.488 |

| The SNS restaurant content I searched for or viewed provided useful information. | 0.833 | −0.320 | 0.726 |

| The SNS restaurant content I’ve searched for or viewed has allowed me to spend economically. | 0.767 | −0.442 | 0.603 |

| Aesthetics (CCR = 0.822, AVE = 0.607) | |||

| The SNS restaurant content I’ve searched for or viewed has stimulated my appetite. | 0.795 | −0.193 | 0.498 |

| SNS restaurant content that I searched for or saw was abundant with aesthetic elements, such as menus and store interiors. | 0.828 | −0.072 | 0.075 |

| I think the SNS restaurant content I have searched for or viewed is pretty. | 0.794 | −0.073 | 0.052 |

| Cognition-based attitude toward message (CCR = 0.731, AVE = 0.773) | |||

| I felt that the SNS restaurant content I encountered was unique. | 0.725 | −0.323 | 0.452 |

| I felt confident after viewing SNS restaurant content. | 0.886 | −0.425 | 0.442 |

| Affect-based attitude toward message (CCR = 0.865, AVE = 0.682) | |||

| I felt happy after viewing SNS restaurant content. | 0.859 | −0.366 | 0.632 |

| I had fun viewing SNS restaurant content. | 0.866 | −0.578 | 0.678 |

| I felt that the SNS restaurant content was attractive. | 0.881 | −0.483 | 0.754 |

| Brand attitude (CCR = 0.861, AVE = 0.675) | |||

| I became familiar with the brand after viewing SNS restaurant content. | 0.816 | −0.499 | 0.698 |

| I began liking the brand after viewing SNS restaurant content. | 0.875 | −0.498 | 1.109 |

| I became interested in the brand after viewing SNS restaurant content. | 0.839 | −0.470 | 1.279 |

| Behavioral intentions (CCR = 0.866, AVE = 0.683) | |||

| We will continue to use the brand after receiving the SNS restaurant content. | 0.863 | −0.532 | 0.929 |

| I am willing to recommend the brand to others after encountering SNS content. | 0.845 | −0.459 | 0.772 |

| We will reuse the brand after encountering SNS restaurant content. | 0.863 | −0.473 | 1.022 |

| Demographics | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 183 | 48.7 |

| Female | 193 | 51.3 |

| Age | ||

| 25~35 | 139 | 37 |

| 36~45 | 130 | 34.7 |

| 46~55 | 80 | 21.4 |

| 56 above | 27 | 6.9 |

| Job | ||

| Agriculture/Forestry/Fishery | 1 | 3 |

| Civil service | 18 | 4.8 |

| Teacher/Academy lecturer | 9 | 2.4 |

| Professional | 26 | 6.9 |

| Executive position | 7 | 1.9 |

| Office worker | 177 | 47.1 |

| Production/labor | 19 | 5.1 |

| Service/sales | 13 | 3.5 |

| Self-employed | 19 | 5.1 |

| Freelancer | 12 | 3.2 |

| Housewife | 47 | 12.5 |

| Student | 14 | 3.7 |

| Inoccupation | 7 | 1.9 |

| Other | 7 | 1.9 |

| Monthly visit frequency | ||

| 4~9 | 227 | 60.4 |

| 10~15 | 106 | 28.1 |

| 16~21 | 29 | 7.7 |

| 22~27 | 4 | 1.1 |

| 28~30 | 10 | 2.7 |

| Length of time using SNS (year) | ||

| 1~2 | 41 | 10.9 |

| 2~3 | 45 | 12.0 |

| 3~4 | 55 | 14.6 |

| 4~5 | 196 | 52.1 |

| Other | 39 | 10.4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Authenticity | 0.730 | |||||||

| 2. Consensus | 0.462 | 0.755 | ||||||

| 3. Usefulness | 0.635 | 0.532 | 0.771 | |||||

| 4. Aesthetics | 0.415 | 0.582 | 0.628 | 0.779 | ||||

| 5. Cognition-based attitude toward message | 0.593 | 0.558 | 0.645 | 0.547 | 0.879 | |||

| 6. Affect-based attitude toward message | 0.537 | 0.515 | 0.686 | 0.637 | 0.744 | 0.826 | ||

| 7. Brand attitude | 0.558 | 0.553 | 0.648 | 0.539 | 0.675 | 0.738 | 0.821 | |

| 8. Behavioral intentions | 0.563 | 0.529 | 0.641 | 0.533 | 0.653 | 0.657 | 0.742 | 0.826 |

| Mean | 3.94 | 4.70 | 4.63 | 4.77 | 4.31 | 4.42 | 4.56 | 4.47 |

| SD | 1.05 | 0.77 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.09 | 1.10 | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Paths | Coefficients | t-Value | p | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1-1 | Authenticity → Cognition-based attitude | 0.289 | 4.080 | 0.000 ** | Supported |

| H1-2 | Authenticity → Affect-based attitude | 0.122 | 1.680 | 0.093 n.s. | Not supported |

| H2-1 | Consensus → Cognition-based attitude | 0.253 | 3.346 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H2-2 | Consensus → Affect-based attitude | 0.030 | 0.393 | 0.694 n.s. | Not supported |

| H3-1 | Usefulness → Cognition-based attitude | 0.420 | 4.407 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H3-2 | Usefulness → Affect-based attitude | 0.439 | 4.421 | 0.000 ** | Supported |

| H4-1 | Aesthetics → Cognition-based attitude | 0.043 | 0.534 | 0.593 n.s. | Not supported |

| H4-2 | Aesthetics → Affect-based attitude | 0.316 | 3.750 | 0.000 ** | Supported |

| H5 | Cognition-based attitude → Brand attitude | 0.577 | 4.818 | 0.000 ** | Supported |

| H6 | Affect-based attitude → Brand attitude | 0.313 | 2.710 | 0.007 ** | Supported |

| H7 | Cognition-based attitude → Behavioral intentions | 0.536 | 3.888 | 0.000 ** | Supported |

| H8 | Affect-based attitude → Behavioral intentions | −0.170 | −1.421 | 0.155 n.s. | Not supported |

| H9 | Brand attitude → Behavioral intentions | 0.512 | 5.130 | 0.000 ** | Supported |

| SMC (R2) | |||||

| Cognition-based attitude toward message | 0.797 (79.7%) | ||||

| Affect-based attitude toward message | 0.671 (67.1%) | ||||

| Brand attitude | 0.754 (75.4%) | ||||

| Behavioral intentions | 0.742 (74.2%) | ||||

| Fit indices | |||||

| χ2 | 425.484 | ||||

| df | 252 | ||||

| χ2/df | 1.688 | ||||

| p | 0.000 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwon, J.-H.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.-K.; Ryu, K. Characteristics of Social Media Content and Their Effects on Restaurant Patrons. Sustainability 2021, 13, 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020907

Kwon J-H, Kim S, Lee Y-K, Ryu K. Characteristics of Social Media Content and Their Effects on Restaurant Patrons. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020907

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwon, June-Hyuk, Sally Kim, Yong-Ki Lee, and Kisang Ryu. 2021. "Characteristics of Social Media Content and Their Effects on Restaurant Patrons" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020907

APA StyleKwon, J.-H., Kim, S., Lee, Y.-K., & Ryu, K. (2021). Characteristics of Social Media Content and Their Effects on Restaurant Patrons. Sustainability, 13(2), 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020907