The Impact of Social and Cultural Norms, Government Programs and Digitalization as Entrepreneurial Environment Factors on Job and Career Satisfaction of Freelancers

Abstract

1. Introduction

Is the job and career satisfaction of freelancers in Slovenia related to their perception of digital technologies support, government programs as well as cultural and social norms?

2. Background Literature and Hypotheses Development

3. Materials and Methods

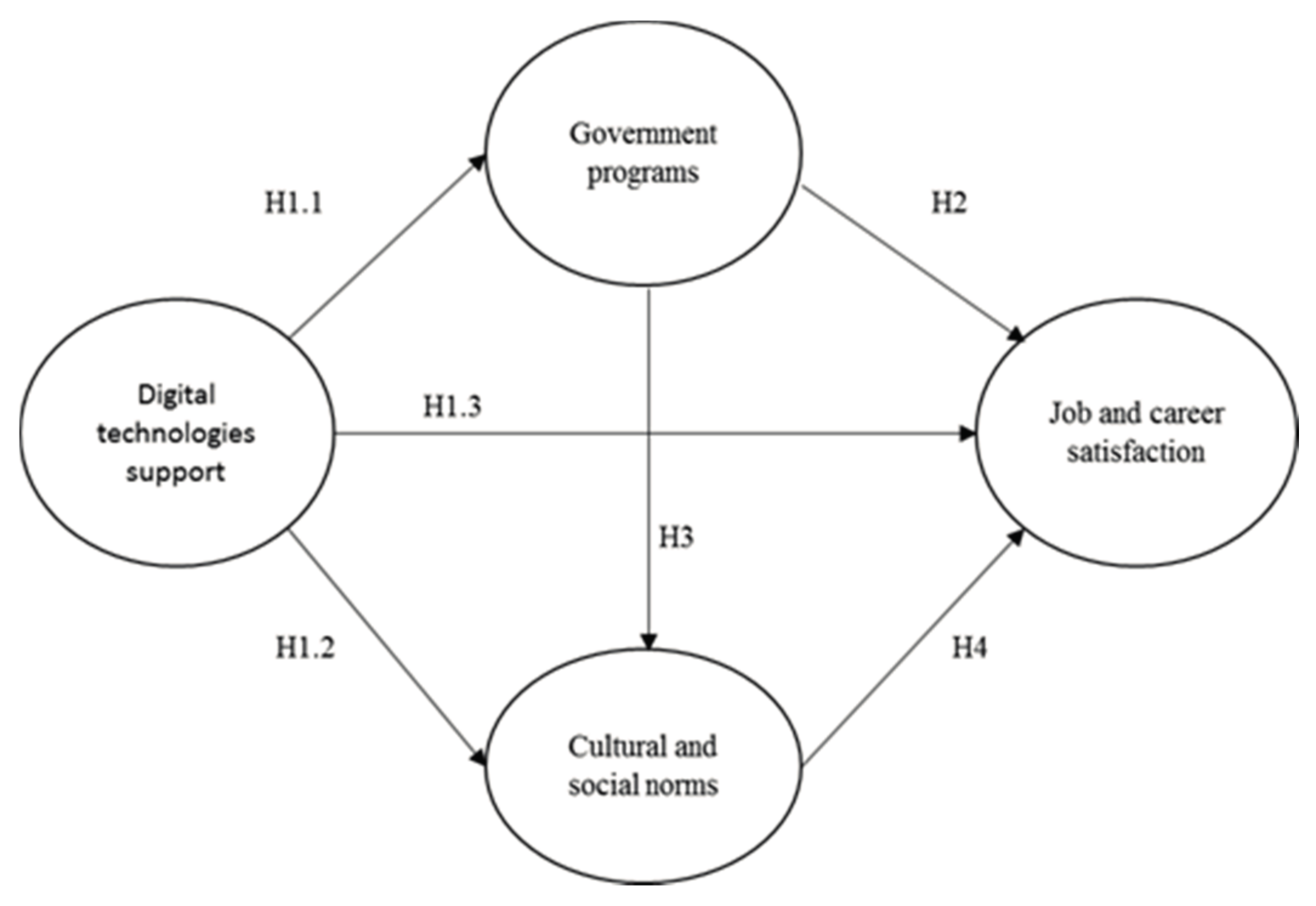

3.1. Conceptual Model

- ➢

- Perceived digital technologies support—the level of perceived national support for the creation of a more favorable environmental infrastructure for a faster and more coordinated development of the information society and for the equal participation of Slovenian stakeholders in the global digital space.

- ➢

- Perceived government programs—the extent of the perceived presence and quality of the government programs that create the conditions for the development of freelance activity.

- ➢

- Perceived cultural and social norms—the perceived extent to which cultural and social norms encourage or discourage freelance activity, leading to new businesses or activities that can potentially increase personal wealth and income.

- ➢

- Perceived job and career satisfaction—the perceived extent to which a pleasant emotional state results from the assessment of one’s career achievements and the assessment of one’s job values.

3.2. Sample Data

3.3. Measures

3.4. Methodology

- ➢

- the measurement model, which indicates the number of factors, the relationship of the various indicators to the factors, and the relationships between the indicator errors (CFA model);

- ➢

- the structural model, indicating how the various factors are related (e.g., direct or indirect effects, no relationship).

3.5. Sample Adequacy

3.6. Data Processing Method—Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

3.6.1. Job and Career Satisfaction

3.6.2. Digital Technology Support

3.6.3. Government Programs

3.6.4. Cultural and Social Norms

3.7. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM)

4. Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Audretsch, D.B. Innovation and Industry Evolution; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The Missing Entrepreneurs 2019: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship; OECD Publications Centre: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K.S.; Wäger, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennen, J.S.; Kreiss, D. Digitalization. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, A.; Cowling, M. The relationship between freelance workforce intensity, business performance and job creation. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Shehab, E.; Tiwari, A.; Baines, T.S.; Lightfoot, H.W.; Benedettini, O.; Kay, J.M. The servitization of manufacturing: A review of literature and reflection on future challenges. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2009, 20, 547–567. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P. Managerial challenges of Industry 4.0: An empirically backed research agenda for a nascent field. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 803–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahuc, P.; Postel-Vinay, F. Temporary jobs, employment protection and labor market performance. Labour Econ. 2002, 9, 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gig Economy Data Hub. Available online: https://www.gigeconomydata.org/basics/what-kinds-work-are-done-through-gigs (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Tran, M.; Sokas, R.K. The gig economy and contingent work: An occupational health assessment. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkley, I. In search of the gig economy. In The Work Foundation; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, A. The Role of Freelancers in the 21st Century British Economy; PCG Publishing Group: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, A.; Cowling, M. The use and value of freelancers: The perspective of managers. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2015, 1, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, A.; Cowling, M. On the critical role of freelancers in agile economies. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, J.; De Moortel, D.; Wilkens, M.; Vanroelen, C. What’s up with the self-employed? A cross-national perspective on the self-employed’s work-related mental well-being. SSM-Popul. Health 2018, 4, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, A.; Van Stel, A. The entrepreneurship enabling role of freelancers: Theory with evidence from the construction industry. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2011, 9, 131–158. [Google Scholar]

- The Online Labour Index. Available online: https://ilabour.oii.ox.ac.uk/online-labour-index/ (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Stephany, F.; Dunn, M.; Sawyer, S.; Lehdonvirta, V. Distancing bonus or downscaling loss? The changing livelihood of US online workers in times of Covid-19. Tijdschr Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, E.C.; Lehdonvirta, V. How COVID-19 Has Hit Offshore Freelancers-and How They Can Bounce Back. 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/covid-19-foreign-freelancers-jobs/ (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- IPSE. The Cost of COVID: How the Pandemic Is Affecting the Self-Employed. Available online: https://www.ipse.co.uk/resource/the-cost-of-covid.html (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- European Commission: The European Digital Strategy. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/content/european-digital-strategy (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- European Commission: Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/shaping-europe-digital-future_en (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Slovenia, R. Digital Slovenia 2020-Development Strategy for the Information Society until 2020; Government of the Republic of Slovenia: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- SORS: The Unemployment Rate at 4.2% in the 2nd Quarter of 2019, the Second Lowest Since We Started to Collect These Data. Available online: https://www.stat.si/StatWeb/en/News/Index/8326 (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Holland, J.L.; Gottfredson, G.D. Using a typology of persons and environments to explain careers: Some extensions and clarifications. Couns. Psychol. 1976, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Prieto, L.; Hinrichs, K.T. Direct and indirect effects of individual and environmental factors on motivation for self-employment. J. Dev. Entrep. 2010, 15, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, P.; Khapova, S.N.; Arthur, M.B. The intelligent career framework as a basis for interdisciplinary inquiry. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.T. The protean career: A quarter-century journey. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Born, A.; Van Witteloostuijn, A. Drivers of freelance career success. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 34, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E. Methods in our madness? Trends in entrepreneurship research. State Art Entrep. 1992, 191, 213. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.; Keilbach, M. Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Reg. Stud. 2004, 38, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B. The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2017, 41, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, M.; Zysman, J. The rise of the platform economy. Issues Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Kergroach, S. Industry 4.0: New challenges and opportunities for the labour market. Форсайт 2017, 11, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Future of Jobs Report; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Chinoracky, R.; Corejova, T. Impact of digital technologies on labor market and the transport sector. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 40, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, R.; Guerrieri, P.; Meliciani, V. The economic impact of digital technologies in Europe. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2014, 23, 802–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Stam, E.; Audretsch, D.B.; O’Connor, A. The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, F.C.; Spigel, B. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. USE Discuss. Pap. Ser. 2016, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: Establishing the framework conditions. J. Technol. Transf. 2017, 42, 1030–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belitski, M.; Heron, K. Expanding entrepreneurship education ecosystems. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, P.A.; Cohen, B. Collision density: Driving growth in urban entrepreneurial ecosystems. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 757–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abri, M.Y.; Rahim, A.A.; Hussain, N.H. Entrepreneurial ecosystem: An exploration of the entrepreneurship model for SMEs in Sultanate of Oman. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnogaj, K.; Rebernik, M. Podjetniška politika in podporno okolje za razvoj podjetništva. Management 2013, 8, 309–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bosma, N.; Kelley, D. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2018/2019 Global Report; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, London Business School: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel, D.S.; Gnyawati, D.R. Environments for Entrepreneurship Development: Key Dimensions and Research Implications. Entrepreneurship. Theory Pract. 1994, 21, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Stuetzer, M.; Audretsch, D.B.; Obschonka, M.; Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Potter, J. Entrepreneurship culture, knowledge spillovers and the growth of regions. Reg. Stud. 2017, 52, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.; Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of organizational management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamorte, W.W. The Social Cognitive Theory; Boston University School of Public Health: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bosma, N.; Hill, S.; Ionescu-Somers, A.; Kelley, D.; Levie, J.; Tarnawa, A. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019/2020 Global Report; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, London Business School: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pennings, J.M. The urban quality of life and entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. J. 1982, 25, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dubini, P. The influence of motivations and environment on business start-ups: Some hints for public policies. J. Bus. Ventur. 1989, 4, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, H. The development of an infrastructure for entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 1993, 8, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, H.; Evans, S. Flexible re-cycling and high-technology entrepreneurship. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1995, 37, 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.N. Wheels in the head: Ridesharing as monitored performance. Surveill. Soc. 2016, 14, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, M. A new class of worker for the sharing economy. Richmond J. Law Technol. 2016, 22, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, J. Microworkers of the gig economy: Separate and precarious. New Labor Forum 2016, 25, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, U.; Knorr, L.; Di Ruggiero, E.; Gastaldo, D.; Zendel, A. Towards an Understanding of Workers’ Experiences in the Global Gig Economy; Global Migration & Health Initiative: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J. What makes an entrepreneur? J. Labor Econ. 1998, 16, 26–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, M.; Frey, B.S. The value of doing what you like: Evidence from the self-employed in 23 countries. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 68, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs-Schündeln, N. On preferences for being self-employed. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2009, 71, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundley, G. Why and when are the self-employed more satisfied with their work? Ind. Relat. A J. Econ. Soc. 2001, 40, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneck, S. Why the self-employed are happier: Evidence from 25 European countries. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Park, S.; Zahra, S.A. Career patterns in self-employment and career success. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.C.; Bolino, M.C. Career patterns of the self-employed: Career motivations and career outcomes. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2000, 38, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, B.H. Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. J. Politi. Econ. 2000, 108, 604–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvereid, L. Organizational employment versus self-employment: Reasons for career choice intentions. Entrep. Theory Pr. 1996, 20, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hytti, U.; Kautonen, T.; Akola, E. Determinants of job satisfaction for salaried and self-employed professionals in Finland. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2034–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S. The rewards of entrepreneurship: Exploring the incomes, wealth, and economic well–being of entrepreneurial households. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2011, 35, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, M.; Jansen, P. Autonomy as a start-up motive. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2006, 13, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, T. Job satisfaction and self-employment: Autonomy or personality? Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 38, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandenHeuvel, A.; Wooden, M. Self-employed contractors and job satisfaction. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1997, 35, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.M.; Peterson, S.J. Culture, entrepreneurial orientation, and global competitiveness. J. World Bus. 2000, 35, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebernik, M.; Širec, K.; Tominc, P.; Crnogaj, K.; Rus, M.; Bradač Hojnik, B. Raznolikost Podjetniških Motivov: GEM Slovenija 2019; Ekonomsko-poslovna Fakulteta, Univerza v Mariboru: Maribor, Slovenia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hayton, J.C.; George, G.; Zahra, S.A. National culture and entrepreneurship: A review of behavioral research. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2002, 26, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P. Culture, structure and regional levels of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1995, 7, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Wiklund, J. Values, beliefs and regional variations in new firm formation rates. J. Econ. Psychol. 1997, 18, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, N.; Sanderson, C.A. 12 life task participation and well-being: The importance of taking part in daily life. Well Being Found. Hedonic Psychol. 2003, 12, 230–243. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Fujita, F. Resources, personal strivings, and subjective well-being: A nomothetic and idiographic approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.C.; Chen, S.C.; Lin, Y.W.; Liao, T.Y.; Lin, Y.E. Social cognitive perspective on factors influencing Taiwanese sport management students’ career intentions. J. Career Dev. 2018, 45, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.C. Social support, career beliefs, and career self-efficacy in determination of Taiwanese college athletes’ career development. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 26, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisnode GVIN. Available online: https://www.bisnode.si/produkti/bisnode-gvin/ (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 140, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, J. Antacedents and Consequences of Lodging Employees’ Career Success: An Application of Motivational Theories. Ph.D. Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA, 29 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, D.W.; Howard, A. Career success and life satisfactions of middle-aged managers. In Competence and Coping Duting Adulthood; Bond, L.A., Rosen, J.C., Eds.; University Press of New England: Hanover, NH, USA, 2013; pp. 258–287. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, T.W. The personality of high earning mba’s in big business 1. Pers. Psychol. 1969, 22, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Bretz, R.D., Jr. Political influence behavior and career success. J. Manag. 1994, 20, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.J.; Klein, G. A discrepancy model of information system personnel turnover. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2002, 19, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S.; Wormley, W.M. Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, V. Beyond the Core: The Role of Co-Working Spaces in Local Economic Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kolsaker, A.; Lee-Kelley, L. Citizens’ attitudes towards e-government and e-governance: A UK study. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Onsman, A.; Brown, T. Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Australas. J. Paramed. 2010, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCoster, J. Overview of Factor Analysis 1998. Available online: http://www.stat-help.com/notes.html (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Janssens, W.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Wijnen, K.; Van Kenhove, P. Marketing Research with SPSS; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Suhr, D.D. Exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis? In Proceedings of the 31st Annual SAS? Users Group International Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–29 March 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A.; Moore, M.T. Confirmatory factor analysis. Handb. Struct. Equ. Model. 2018, 18, 361–379. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Factor Analysis Using SPSS; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L. Figuring out factors: The use and misuse of factor analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry 1994, 39, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, N. A note on how to conduct a factor-based PLS-SEM analysis. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. WarpPLS User Manual: Version 6.0; ScriptWarp Systems: Laredo, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prectice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. WarpPLS user manual: Version 7.0; ScriptWarp Systems: Laredo, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. An examination of the validity of two models of attitude. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1981, 16, 323–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- The Gig Economy and Alternative Work Arrangements, Gallup, Washington. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/file/workplace/240878/Gig_Economy_Paper_2018.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- European Commission: Developments and Forecasts of Changing Nature of Work. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/foresight/topic/changing-nature-work/developments-forecasts-changing-nature-work_en (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- The IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking 2020 Results. Available online: https://www.imd.org/wcc/world-competitiveness-center-rankings/world-digital-competitiveness-rankings-2020/ (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Črnko, A. Slovenija še vedno brez strategije digitalizacije. 2020. Available online: https://svetkapitala.delo.si/ikonomija/slovenija-se-vedno-brez-strategije-digitalizacije/ (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Walwei, U. Digitalization and Structural Labour Market Problems: The Case of Germany; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission: Digital Economy and Society Index Slovenia. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/scoreboard/slovenia (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Manyika, J.; Lund, S.; Bughin, J.; Robinson, K.; Mischke, J.; Mahajan, D. Independent work: Choice, necessity, and the gig economy. McKinsey Glob. Inst. 2016, 2016, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

| Criterion | Level of Acceptance | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (BTS) | Chi-Square; p < 0.05 | Field, 2005 [100] |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) | >0.5 | Kaiser, 1974 [101] |

| Communalities values | >0.5 | Field, 2009 [102] |

| Factor loadings | >0.5 | Janssens et al., 2008 [96] |

| Total variance explained | 60% (in some cases even less) | Hair et al., 2014 [103] Streiner, 1994 [104] |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | >0.6 | Janssens et al., 2008 [96] |

| Construct | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity; Chi-Square; p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Job and Career Satisfaction (JCS) | 0.833 | 0.000 |

| Digital Technology Support (DTS) | 0.664 | 0.000 |

| Government Programs (GP) | 0.854 | 0.000 |

| Cultural and Social Norms (CSN) | 0.826 | 0.000 |

| Variable Label | Variable | Communalities | Factor Loadings Factor JCS |

|---|---|---|---|

| q1_JCS | I am satisfied with the success I have achieved in my career. | 0.714 | 0.845 |

| q2_JCS | I am satisfied with the way I feel about my job as a whole. | 0.793 | 0.890 |

| q3_JCS | I am satisfied with the opportunities to use my abilities on the job. | 0.572 | 0.756 |

| q4_JCS | I am satisfied with the progress I have made towards meeting my goals for my overall daily life. | 0.622 | 0.789 |

| q5_JCS | I am satisfied with the progress I have made towards meeting my goals for the development of new skills. | 0.689 | 0.829 |

| q6_JCS | I am satisfied with the support I receive from my clients. | 0.549 | 0.741 |

| Number of Items | 6 | ||

| Total Variance Explained for Construct | 65.60 | ||

| Cronbach’s Alpha for Construct | 0.893 | ||

| Variable Label | Variable | Communalities | Factor Loadings Factor 1 Digitalization (DT) | Factor Loadings Factor 2 Digital Skills Acquisition Need (DSAN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| q1_DTS | In my country, there are systems that allow citizens to access and use electronic services in a secure and reliable way. | 0.569 | 0.692 | |

| q2_DTS | In my country, people are well informed about the opportunities in the digital labour market. | 0.537 | 0.719 | |

| q3_DTS | In my country, there are programs that support regional coworking spaces. | 0.560 | 0.729 | |

| q4_DTS | In my country, the education sector should give more priority to the acquisition of digital skills. | 0.907 | 0.952 | |

| q5_DTS | Government support is sufficient for my country to be considered a digitized country. | 0.690 | 0.782 | |

| Number of Items of Construct | 5 | |||

| Total Variance Explained for Construct | 65.252 | |||

| Cronbach’s Alpha for Construct | 0.608 | |||

| Variable Label | Variable | Communalities | Factor Loadings Factor GP |

|---|---|---|---|

| q2_GP | Science parks and business incubators provide effective support for freelance activity. | 0.576 | 0.759 |

| q3_GP | There is an adequate number of government programs for freelance activity. | 0.778 | 0.882 |

| q4_GP | The people working for government agencies are competent and effective in supporting freelance activity. | 0.713 | 0.844 |

| q5_GP | Almost anyone who needs help from a government program for a freelance activity can find what they need. | 0.791 | 0.890 |

| q6_GP | Government programs aimed at supporting freelance activity are effective. | 0.784 | 0.885 |

| Number of Items | 5 | ||

| Total Variance Explained for Construct | 72.839 | ||

| Cronbach’s Alpha for Construct | 0.906 | ||

| Variable Label | Variable | Communalities | Factor Loadings Factor CSN |

|---|---|---|---|

| q1_CSN | The national culture is highly supportive of individual success achieved through personal efforts. | 0.702 | 0.838 |

| q2_CSN | The national culture emphasizes self-sufficiency, autonomy, and personal initiative. | 0.790 | 0.889 |

| q3_CSN | The national culture encourages entrepreneurial risk-taking. | 0.779 | 0.883 |

| q4_CSN | The national culture encourages creativity and innovativeness. | 0.819 | 0.905 |

| q5_CSN | The national culture emphasizes the responsibility that individual (rather than the collective) has in managing his or her own life. | 0.591 | 0.769 |

| Number of Items | 5 | ||

| Total Variance Explained for Construct | 73.616 | ||

| Cronbach’s Alpha for Construct | 0.908 | ||

| Criterion | Level of Acceptance |

|---|---|

| Indicator Loadings | >0.50 |

| Indicator weight | positive |

| Statistical significance of the indicator loading and indicator weight | p < 0.05 |

| Variance inflation factor | ≤5; ≤10.0 |

| Effect size | ≥0.02 |

| Construct | Variable | Mean | SD | Indicator Loading | Indicator Weight | p Value | VIF | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JCS | q1_JCS | 5.75 | 1.100 | 0.836 | 0.215 | <0.001 | 3.019 | 0.180 |

| q2_JCS | 5.92 | 1.113 | 0.882 | 0.227 | <0.001 | 3.900 | 0.201 | |

| q3_JCS | 5.85 | 1.267 | 0.746 | 0.192 | 0.003 | 1.831 | 0.143 | |

| q4_JCS | 5.84 | 1.123 | 0.782 | 0.201 | 0.002 | 2.259 | 0.157 | |

| q5_JCS | 5.68 | 1.144 | 0.829 | 0.214 | <0.001 | 2.333 | 0.177 | |

| q6_JCS | 5.88 | 1.068 | 0.742 | 0.191 | 0.003 | 1.690 | 0.142 | |

| DT | q1_DTS | 4.40 | 1.537 | 0.686 | 0.330 | <0.001 | 1.246 | 0.227 |

| q2_DTS | 3.55 | 1.504 | 0.728 | 0.350 | <0.001 | 1.306 | 0.255 | |

| q3_DTS | 4.33 | 1.437 | 0.699 | 0.337 | <0.001 | 1.273 | 0.235 | |

| q5_DTS | 3.78 | 1.540 | 0.767 | 0.369 | <0.001 | 1.389 | 0.283 | |

| GP | q2_GP | 3.40 | 1.484 | 0.698 | 0.207 | 0.001 | 1.495 | 0.145 |

| q3_GP | 2.76 | 1.469 | 0.840 | 0.249 | <0.001 | 2.229 | 0.209 | |

| q4_GP | 2.52 | 1.313 | 0.829 | 0.246 | <0.001 | 2.434 | 0.204 | |

| q5_GP | 2.59 | 1.362 | 0.880 | 0.261 | <0.001 | 3.026 | 0.230 | |

| q6_GP | 2.65 | 1.325 | 0.845 | 0.251 | <0.001 | 2.398 | 0.212 | |

| CSN | q1_CSN | 3.07 | 1.703 | 0.820 | 0.227 | <0.001 | 2.645 | 0.186 |

| q2_CSN | 3.16 | 1.578 | 0.879 | 0.243 | <0.001 | 3.268 | 0.213 | |

| q3_CSN | 3.01 | 1.569 | 0.884 | 0.244 | <0.001 | 3.605 | 0.216 | |

| q4_CSN | 3.22 | 1.585 | 0.895 | 0.247 | <0.001 | 3.857 | 0.221 | |

| q5_CSN | 3.40 | 1.702 | 0.771 | 0.213 | <0.001 | 1.894 | 0.164 |

| Construct | R-Square | Adjusted R-Square | Composite Reliability | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE | VIF | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JCS | 0.054 | 0.040 | 0.916 | 0.890 | 0.647 | 1.041 | 0.059 |

| DT | - | - | 0.812 | 0.691 | 0.519 | 1.556 | |

| GP | 0.339 | 0.336 | 0.911 | 0.877 | 0.674 | 1.863 | 0.344 |

| CSN | 0.347 | 0.340 | 0.929 | 0.904 | 0.724 | 1.526 | 0.351 |

| Factor | GP | CSN | DT | JCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP | (0.821) | |||

| CSN | 0.570 *** | (0.851) | ||

| DT | 0.581 *** | 0.429 *** | (0.721) | |

| JCS | 0.381 ** | 0.168 ** | 0.167 ** | (0.804) |

| Criterion | General Rule for Acceptable Fit If Data Are Continuous | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Average path coefficient (APC) | acceptable if p < 0.05 | APC = 0.252, p < 0.001 |

| Average R-squared (ARS) | acceptable if p < 0.05 | ARS = 0.247, p < 0.001 |

| Average adjusted R-squared (AARS) | acceptable if p < 0.05 | AARS = 0.239, p < 0.001 |

| Average block VIF (AVIF) | acceptable if ≤ 5, ideally ≤ 3.3 | AVIF = 1.553 |

| Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) | acceptable if ≤ 5, ideally ≤ 3.3 | AFVIF = 1.497 |

| Tenenhaus GoF (GoF) | small ≥ 0.1, medium ≥ 0.25, large ≥ 0.36 | GoF = 0.398 |

| Simpson’s paradox ratio (SPR) | acceptable if ≥ 0.7, ideally = 1 | SPR = 0.833 |

| R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR) | acceptable if ≥ 0.9, ideally = 1 | RSCR = 0.999 |

| Statistical suppression ratio (SSR) | acceptable if ≥ 0.7 | SSR = 1.000 |

| Nonlinear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR) | acceptable if ≥ 0.7 | NLBCDR = 1.000 |

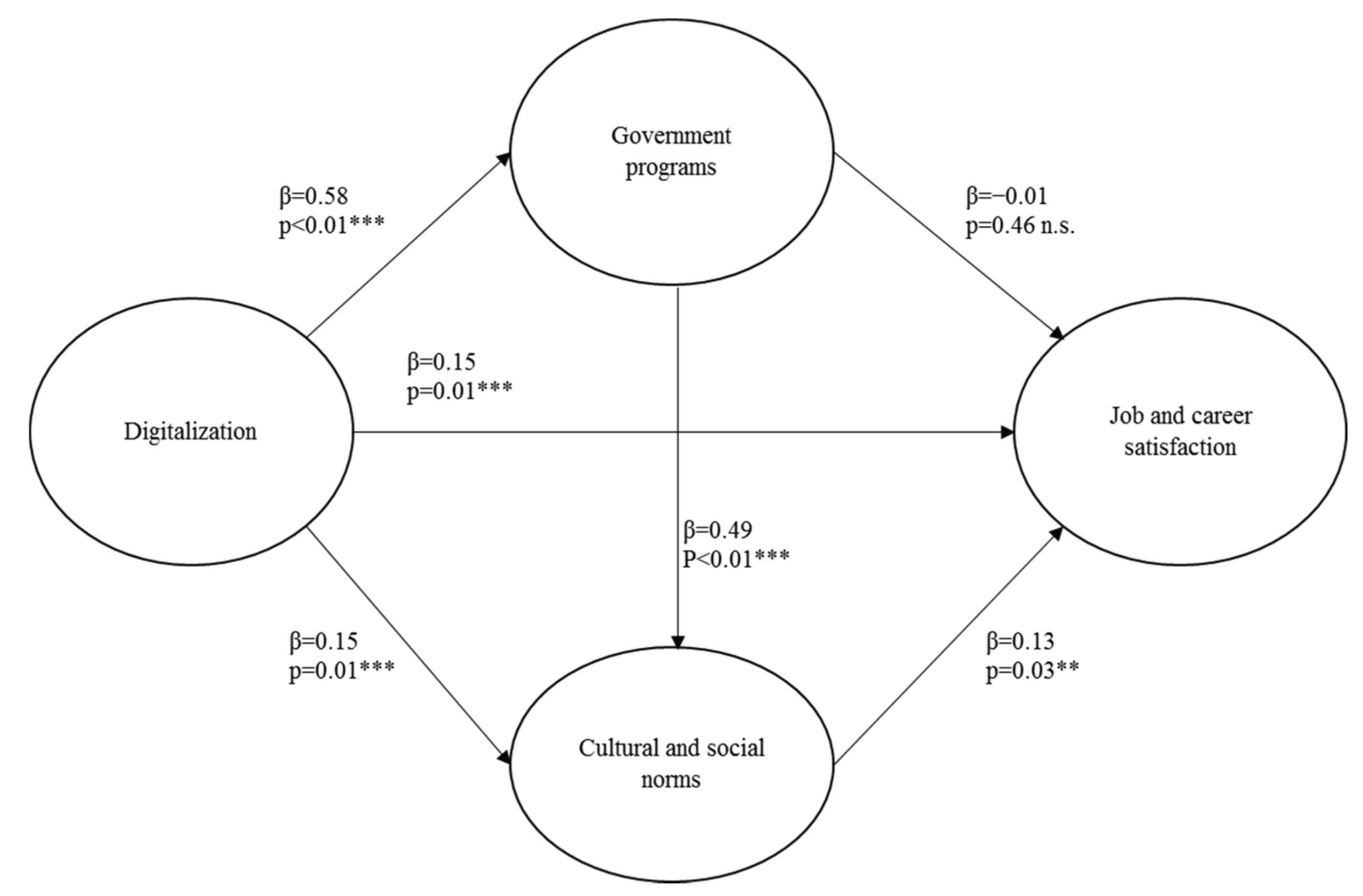

| Hypothesis | Impact | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|

| H1.1 | 0.15 *** | 0.339 |

| H1.2 | 0.58 *** | 0.191 |

| H1.3 | 0.15 *** | 0.041 |

| H2 | −0.01 n.s. | 0.008 |

| H3 | 0.49 *** | 0.279 |

| H4 | 0.13 ** | 0.025 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huđek, I.; Tominc, P.; Širec, K. The Impact of Social and Cultural Norms, Government Programs and Digitalization as Entrepreneurial Environment Factors on Job and Career Satisfaction of Freelancers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020779

Huđek I, Tominc P, Širec K. The Impact of Social and Cultural Norms, Government Programs and Digitalization as Entrepreneurial Environment Factors on Job and Career Satisfaction of Freelancers. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020779

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuđek, Ivona, Polona Tominc, and Karin Širec. 2021. "The Impact of Social and Cultural Norms, Government Programs and Digitalization as Entrepreneurial Environment Factors on Job and Career Satisfaction of Freelancers" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020779

APA StyleHuđek, I., Tominc, P., & Širec, K. (2021). The Impact of Social and Cultural Norms, Government Programs and Digitalization as Entrepreneurial Environment Factors on Job and Career Satisfaction of Freelancers. Sustainability, 13(2), 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020779