Significance of Allotment Gardens in Urban Green Space Systems and Their Classification for Spatial Planning Purposes: A Case Study of Poznań, Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

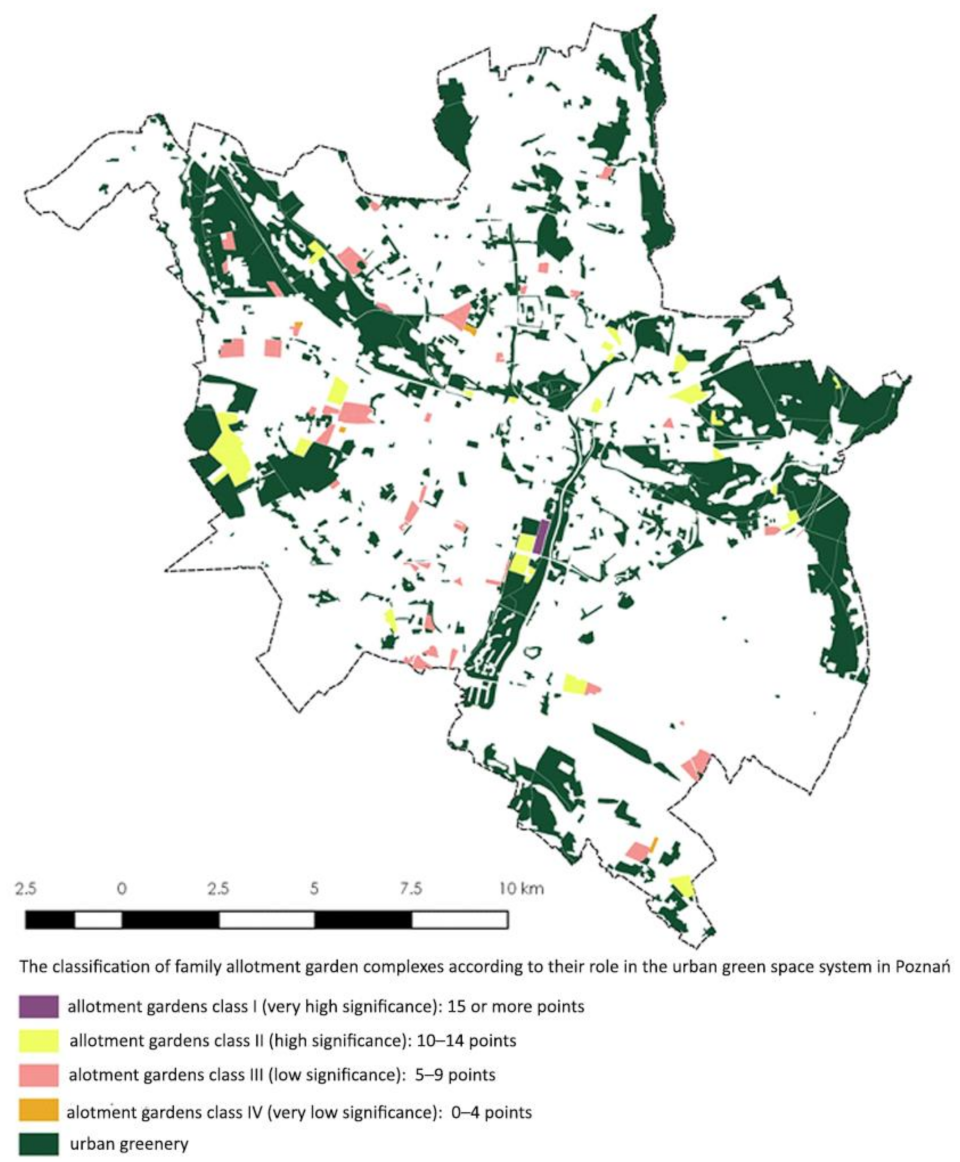

- Class I (very high significance in city green space system): 15 points or more;

- Class II (high significance in city green space system): 10–14 points;

- Class III (low significance in city green space system): 5–9 points;

- Class IV (very low significance in city green space system): 4 points or less.

3. Results

3.1. Area of Allotment Gardens

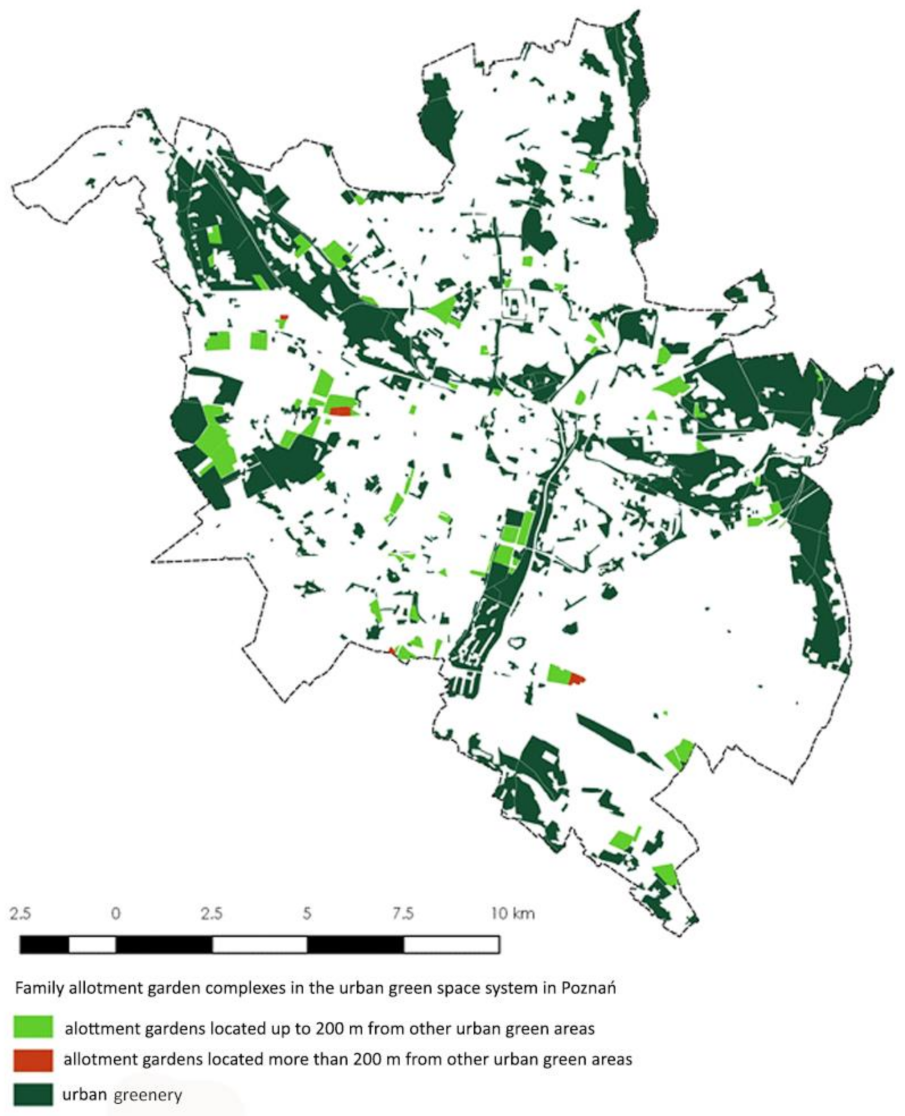

3.2. Location of Individual Allotment Gardens in Relation to Their Surroundings

3.3. Classification of Allotment Gardens According to Their Significance in the Urban Green Space System in Poznań

3.4. Spatial Policy of the City

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The study showed that allotment gardens are important areal and spatial elements of the green space system in Poznań. The occurrence of allotment gardens in green wedges is essential as they are the most important and sustainable spatial structures of the urban greenery system. The current use of almost 75.6% of all allotment gardens in Poznań will not change according to the spatial planning documents.

- A classification and valuation method was used in the study to determine the role of individual allotment gardens in the green space system in Poznań. Over 30% of the allotment gardens were of high significance in the green space system of the city. The majority of allotment gardens were identified in class III (low significance).

- The analysis of urban planning documents showed that the area of allotment gardens in Poznań will be decreasing. There are also plans to liquidate the allotment gardens that were valuated as facilities of high significance to the urban green space system. Taking into account the results of the presented classification, these plans should be revised. In the context of the vital investment needs of the city, the functions of the allotment gardens that are least valuable for the city green space system (class IV) may be changed.

- This classification method based on individual internal and external features of allotment gardens creates a comprehensive valuation of their significance in a city green space system for the purposes of spatial planning. Use of the developed classification when creating planning documents could influence the decision-making process regarding the liquidation of allotment gardens and the preservation of the most valuable objects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poniży, L.; Stachura, K. Future of Allotment Gardens in the Context of City Spatial Policy – A Case Study of Poznań. Quaest. Geogr. 2017, 36, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buchel, S.; Frantzeskaki, N. Citizens’ Voice: A Case Study about Perceived Ecosystem Services by Urban Park Users in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.; Chen, W.Y. Recreation–amenity Use and Contingent Valuation of Urban Greenspaces in Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembecka, A.; Kwartnik-Pruc, A. An Analysis of the Changes in the Structure of Allotment Gardens in Poland and of the Process of Regulating Legal Status. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biglin, J. Embodied and Sensory Experiences of Therapeutic Space: Refugee Place-Making Within an Urban Allotment. Heal. Place 2020, 62, 102309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.E.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R.; Pauleit, S. Adapting Cities for Climate Change: The Role of the Green Infrastructure. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tratalos, J.; Fuller, R.; Warren, P.H.; Davies, R.G.; Gaston, K.J. Urban Form, Biodiversity Potential and Ecosystem Services. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, E.; Szumacher, I. Rola ogrodów działkowych W Krajobrazie lewobrzeżnej Warszawy. Problemy Ekologii Kra-Jobrazu 2008, 22, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, S. Green Infrastructure Rising: Best Practices in Stormwater Management; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pauleit, S.; Duhme, F. Assessing the Environmental Performance of Land Cover Types for Urban Planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 52, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.; Werner, P.; Kelcey, J.G. Urban Biodiversity and Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler, M.; Allen, W.; Meurk, C. Conserving Urban Biodiversity? Creating Green Infrastructure Is Only the First Step. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, D.; Moretti, M. A Comprehensive Dataset on Cultivated and Spontaneously Growing Vascular Plants in Urban Gardens. Data Brief 2019, 25, 103982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szulczewska, B.; Cieszewska, A.; Prove, C. Urban Agriculture and “early birds” Initiatives in Warsaw. Problemy Ekologii Krajobrazu 2013, 36, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Spilková, J.; Vágner, J. The Loss of Land Devoted to Allotment Gardening: The Context of the Contrasting Pressures of Urban Planning, Public and Private Interests in Prague, Czechia. Land Use Policy 2016, 52, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowińska-Świerkosz, B.; Michalik-Śnieżek, M.; Bieske-Matejak, A. Can Allotment Gardens (AGs) Be Considered an Example of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) Based on the Use of Historical Green Infrastructure? Sustainability 2021, 13, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS Główny Urząd Statystyczny (Central Statistical Office.) Bank Danych Lokalnych. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/dane/teryt/Tablica (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Kim Są Polscy działkowcy? Badanie Wykonane Przez Krajową Radę Polskiego Związku Działkowców Przy współudziale okręgowych zarządów PZD I zarządów ROD; Krajowa Rada Polskiego Związku Działkowców: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. Available online: http://pzd.pl/archiwum/strona.php?421 (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Szczepańska, M. Family Allotment Gardens - the Case of the Poznań Agglomeration. Eur. XXI 2017, 32, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewińska, J. Klimat Miasta; IGPiK: Kraków, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlikowska-Piechotka, A. Tradycja ogrodów działkowych W Polsce; Novae Res – Wydawnictwo Innowacyjne: Gdynia, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg, J.; Bergier, T.; Lisicki, P. Usługi ekosystemów W Praktyce a Ogrody działkowe. In Ogrody działkowe W Mi-Astach—Bariera Czy wartość? Kosmala, M., Ed.; PZiTS Oddział Toruń: Toruń, Poland, 2013; pp. 158–168. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel, S.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. Social–ecological Memory in Urban gardens—Retaining the Capacity for Management of Ecosystem Services. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Allotment Gardens in Europe. In Urban Allotment Gardens in Europe; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 115–141. [CrossRef]

- Cabral, I.; Keim, J.; Engelmann, R.; Kraemer, R.; Siebert, J.; Bonn, A. Ecosystem Services of Allotment and Community Gardens: A Leipzig, Germany Case Study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 23, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemeyer, J.; Camps-Calvet, M.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Barthel, S.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Stewardship of Urban Ecosystem Services: Understanding the value(s) of Urban Gardens in Barcelona. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 170, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, I.; Fernandes, C.; Castiglione, B.; Costa, L. Characteristics and Motivations of Potential Users of Urban Allotment Gardens: The Case of Vila Nova De Gaia Municipal Network of Urban Allotment Gardens. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, J.L.; Childs, D.; Dobson, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Warren, P.H.; Leake, J.R. Feeding a City – Leicester As a Case Study of the Importance of Allotments for Horticultural Production in the UK. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, C.; Hofmann, M.; Frey, D.; Moretti, M.; Bauer, N. Psychological Restoration in Urban Gardens Related to Garden Type, Biodiversity and Garden-Related Stress. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 198, 103777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Jagt, A.P.; Szaraz, L.R.; Delshammar, T.; Cvejić, R.; Santos, A.; Goodness, J.; Buijs, A. Cultivating Nature-Based Solutions: The Governance of Communal Urban Gardens in the European Union. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Matarrita-Cascante, D. The Influence of Emotional and Conditional Motivations on gardeners’ Participation in Community (allotment) Gardens. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 42, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Allotment Gardens in Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 201–228. [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, A.; Wiskerke, J.S.C. Sustainable Food Planning: Evolving Theory and Practice. In Sustainable Food Planning: Evolving Theory and Practice; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allotment Gardens Act of 13 December 2013 (Ustawa O Rodzinnych Ogrodach działkowych Dz.U 2014 Poz. 40). Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20140000040/U/D20140040Lj.Pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Nature Conservation Act of 16 April 2004 (Ustawa O Ochronie Przyrody Dz.U. 2004 Nr 92 Poz. 880). Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20040920880/T/D20040880L.Pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Kacprzak, E.; Maćkiewicz, B.; Szczepańska, M. Legal Regulations and the Development of German and Polish Allotment Gardens in the Context of the Production Function. Ruch- Prawniczy Èkon. i Socjol. 2020, 82, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, J.M.P.; Conrad, E. Exploring the Feasibility of Setting up Community Allotments on Abandoned Agricultural Land: A Place, People, Policy Approach. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.C.; Egerer, M.H.; Fouch, N.; Clarke, M.; Davidson, M.J. Comparing Community Garden Typologies of Baltimore, Chicago, and New York City (USA) to Understand Potential Implications for Socio-Ecological Services. Urban Ecosyst. 2019, 22, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urban Atlas. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/local/Urban-Atlas. (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Dąbrowska-Milewska, G. Standardy Urbanistyczne Dla terenów Mieszkaniowych-Wybrane Zagadnienia. Architecturae Et Artibus 2010, 2, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dzikowska, A.; Krzemińska, A.; Zareba, A. Allotment Gardens As Significant Element Integrating Greenery System of the City. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Prague, Czech Republic, 3–7 September 2018; IOP Publishing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019; Volume 221, p. 012121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszeja, E.; Gałecka-Drozda, A. Współczesna Interpretacja Idei poznańskiego Systemu Zieleni Miejskiej W kontekście Strate-Gii Miasta zrównoważonego. Studia Miejskie 2015, 19, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development (SUiKZP) 2014, Municipal Urbanism Workshop (Miejska Pra-Cownia Urbanistyczna Poznan). Available online: www.mpu.pl/plany.Php (accessed on 6 October 2018).

- Dymek, D. Użytkowanie I Kierunki Rozwoju Rodzinnych ogrodów działkowych Na przykładzie Poznania. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Life Sciences in Poznań, Poznań, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Teuber, S.; Schmidt, K.; Kühn, P.; Scholten, T. Engaging with Urban Green Spaces—A Comparison of Urban and Rural Allotment Gardens in Southwestern Germany. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 43, 126381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domene, E.; Saurí, D. Urbanization and Class-Produced Natures: Vegetable Gardens in the Barcelona Metropolitan Region. Geoforum 2007, 38, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duś, E. Miejsce I Rola ogrodów działkowych W Przestrzeni Miejskiej. Geographia. Studia Et Dissertationes 2011, 33, 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.; Dean, A.; Barry, V.; Kotter, R. Places of Urban Disorder? Exposing the Hidden Nature and Values of an English Private Urban Allotment Landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 169, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dobson, M.C.; Edmondson, J.L.; Warren, P.H. Urban Food Cultivation in the United Kingdom: Quantifying Loss of Allotment Land and Identifying Potential for Restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 199, 103803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourias, J.; Aubry, C.; Duchemin, E. Is Food a Motivation for Urban Gardeners? Multifunctionality and the Relative Importance of the Food Function in Urban Collective Gardens of Paris and Montreal. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maćkiewicz, B.; Szczepańska, M.; Kacprzak, E.; Fox-Kämper, R. Between Food Growing and Leisure: Contemporary Allotment Gardeners in Western Germany and Poland. DIE ERDE J. Geogr. Soc. Berlin 2021, 152, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkup, R.; Pytel, S. Ogrody Działkowe (ROD) W Przestrzeni dużego Miasta. Przykład Łodzi. Prace Komisji Krajobrazu Kulturowego 2016, 32, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Szkup, R. Użytkowanie Rodzinnych ogrodów działkowych (ROD) Przez społeczność wielkomiejską, przykład Łodzi; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic Features | Ranges | Points |

|---|---|---|

| Internal | ||

| Age (years) | 0–20 | 1 |

| 21–40 | 2 | |

| 41–60 | 3 | |

| 61–80 | 4 | |

| Over 81 | 5 | |

| Area (ha) | Up to 2 | 1 |

| 2.1–5 | 2 | |

| 5.1–20 | 3 | |

| Over 20 | 4 | |

| External | ||

| Relation to urban green system | Allotment garden located outside an urban greenery system (green wedges in Poznań), not connected with other green spaces | 0 |

| Allotment garden located outside an urban greenery system (green wedges in Poznań), connected with other green spaces | 1 | |

| Allotment garden located partly within the urban greenery system (green wedges in Poznań) or connected to other green spaces | 2 | |

| Allotment garden located entirely within the urban greenery system (green wedges in Poznań) | 4 | |

| Surface waters | Allotment garden without surface waters within 300 m | 0 |

| Allotment garden with surface waters within 300 m | 2 | |

| Negative pressure of surrounding | Main roads, railways, industrial zones, airports and sewage treatment plants as a source of pollution, noise or odors | −4 −2 −1 0 |

| Maximum number of points | 17 | |

| Managing Institutions | Form of Green Space | Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|

| Poznań Municipal Greenery Administration | Parks | 327.5 |

| Green squares | 96.2 | |

| Cemeteries | 2.0 | |

| Unarranged green space | 87.0 | |

| Total | 512.7 | |

| Green Space Department, City Roads Administration | Street greenery | 951.5 |

| Poznań Sports and Recreation Centres | Green space for sports and recreation | 58.8 |

| Department of Transport and Green Space, Poznań City Council | 20.2 | |

| Poznań Forest Administration | 2560.5 | |

| State Forests | 2501.2 | |

| Other forests | 437.4 | |

| Form of Green Space | Area per Capita (m2) |

|---|---|

| Allotment gardens | 15.0 |

| Parks | 6.1 |

| Green squares | 1.8 |

| Cemeteries | 0.0 |

| Unarranged green space | 1.6 |

| Road greenery | 17.7 |

| Green space for sports and recreation | 1.1 |

| Green space under administration of Department of Transport and Green Space, Poznań City Council | 0.4 |

| Poznań Forest Administration | 47.5 |

| State Forests | 23.2 |

| Other forests | 8.1 |

| Name of Allotment Garden | Total Number of Allotment Gardens with Criterion | % Allotment Gardens in Poznań |

|---|---|---|

| Urban greenery < 200 m | 81 | 94.2 |

| Surface waters < 300 m | 32 | 37.2 |

| Main roads > 200 m | 8 | 9.3 |

| Railways < 500 m | 25 | 29.1 |

| Industrial zones < 500 m | 29 | 33.7 |

| Airports < 1000 m | 27 | 31.4 |

| Sewage treatment plants < 500 m | 3 | 3.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dymek, D.; Wilkaniec, A.; Bednorz, L.; Szczepańska, M. Significance of Allotment Gardens in Urban Green Space Systems and Their Classification for Spatial Planning Purposes: A Case Study of Poznań, Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131911044

Dymek D, Wilkaniec A, Bednorz L, Szczepańska M. Significance of Allotment Gardens in Urban Green Space Systems and Their Classification for Spatial Planning Purposes: A Case Study of Poznań, Poland. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):11044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131911044

Chicago/Turabian StyleDymek, Dominika, Agnieszka Wilkaniec, Leszek Bednorz, and Magdalena Szczepańska. 2021. "Significance of Allotment Gardens in Urban Green Space Systems and Their Classification for Spatial Planning Purposes: A Case Study of Poznań, Poland" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 11044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131911044

APA StyleDymek, D., Wilkaniec, A., Bednorz, L., & Szczepańska, M. (2021). Significance of Allotment Gardens in Urban Green Space Systems and Their Classification for Spatial Planning Purposes: A Case Study of Poznań, Poland. Sustainability, 13(19), 11044. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131911044